Highlights

-

•

The use of seat belts is associated with a unique injury profile collectively termed “the seat belt syndrome”.

-

•

The typical findings of peritonitis might not be present initially.

-

•

The chances of intra abdominal injury in the presence of seat belt sign increase eight folds.

Keywords: Seat belt syndrome, Seat belt injuries, Blunt hollow viscus injury, Mesenteric injury

Abstract

Introduction

Seat belt injuries are not uncommon. The use of seat belts is associated with a unique injury profile collectively termed “the seat belt syndrome”. The aim is to aid in the early diagnosis of seat belt injuries.

Case presentation

Two different patients presented to the emergency after sustaining a motor vehicle accident. Both were the drivers, restrained and had a frontal impact. On presentation they were hemodynamically stable with mild tenderness on the abdomen and the abdominal computed tomography (CT) did not show any signs of bowel or mesenteric injuries. The signs of peritonitis became obvious after 24 h in one case and after 3 days in the other.

Discussion

Early diagnosis provides better outcomes for patients with seat belt injuries, but this remains a challenge to trauma surgeons. The typical findings of peritonitis might not be present initially. The presence of abdominal wall ecchymosis (seat belt sign) increases the chance of intraabdominal injuries by eight folds.

Conclusion

Clinical signs of intestinal injuries might not be obvious on presentation. In the presence of seat belt sign the possibility of bowl injury must be suspected. Admit the patient for observation even if no clinical or radiological findings are present at presentation.

1. Introduction

The use of seat belts has increased significantly in the last two decades, leading to a decrease in mortality from road traffic accidents (RTA). While a seat belt of good design and properly worn will prevent the occupants of a car being flung violently against the steering wheel, dashboard, or wind- screen, the force applied to the body by the restraining effect of the belt is considerable and increase the chance of intra-abdominal injuries [1]. The use of seat belts is associated with a unique injury profile collectively termed “the seat belt syndrome”. Skin abrasions of the neck, chest and abdomen – i.e., the classic seat belt sign – indicate a high chance of an internal injury.

Although it is now generally accepted that injuries due to the seat belt can happen, few articles have been published on this subject and focused on the delayed presentation. We believe that this article will help in the early diagnosis of seat belt injuries. We present two cases of intra-abdominal injuries due to seat belt with no clear signs of intra-abdominal injuries on presentation. This article has been reported in line with the CARE criteria [2].

2. Case presentation

2.1. Case 1

A 24 years old female, with no previous medical or surgical history, presented to emergency after sustaining road traffic accident, she was the driver, wearing seat belt and had front impact and airbag deployed. On presentation, she was conscious, breathing spontaneously, vitally stable and there were multiple abrasions on the nose and right hand with deformity in her left forearm. Abdominal examination showed seat belt sign and mild localized tenderness at the site of the abrasions. Computed tomography (CT) abdomen showed no significant abdominal or pelvic findings.

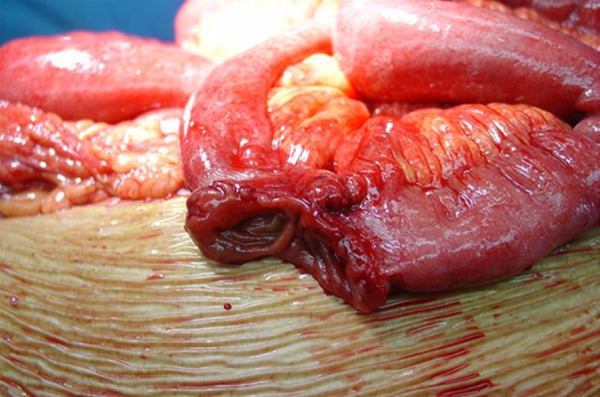

Patient admitted, open reduction and internal fixation of radius and ulna shaft done. On day 3 she started complaining of abdominal pain not responding to analgesia associated with vomiting, she was tachycardic, febrile and abdomen was tender with guarding. She was posted of exploratory laparotomy which revealed perforation in the ileum (Fig. 1). Resection and anastomosis of the involved segment done. The post-operative course in regard to enteral feeding and mobilization was unremarkable. The drain was removed on a timely manner as planned. The wound underwent proper primary healing and sutures removed on time.

Fig. 1.

Ileum perforation.

2.2. Case 2

A 31 years old gentleman, with no previous medical or surgical history, presented to emergency after getting involved in a motor vehicle accident. He was the driver and wearing the seat belt. On presentation he was conscious, breathing spontaneously and vitally stable. He was complaining of lower back pain and abdominal pain. Abdominal examination showed seat belt sign (Fig. 2), with mild generalized tenderness. He also had an open fracture of right elbow.

Fig. 2.

Seat belt sign.

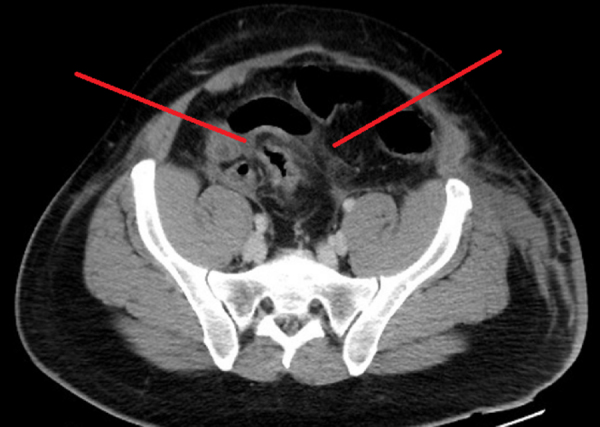

CT abdomen showed tear in the abdominal wall muscles and subcutaneous stranding. There were no signs of intra-abdominal injuries. Patient was admitted, open reduction and internal fixation of right elbow was done. 24 h later the abdominal pain increased and the tenderness was localized in the lower abdomen. He was tachycardic (heart rate 117/min). CT abdomen repeated and showed mesenteric fat stranding more prominent in the pelvis with surrounding minimal free fluid collection (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CT abdomen after 24 h showing mesenteric stranding fluid collection and ileum thickening.

Exploratory Laparotomy was done and showed mesenteric injury with devascularization of the terminal ileum (Fig. 4). Right hemicolectomy with side to side anastomosis was done. Post-operative day 4, patient developed wound dehiscence and was taken for exploratory laparotomy which showed anastomotic leak. Resection was done with ileocolic anastomosis. Post-operative the patient developed wound infection which was managed by dressing and delayed primary closure.

Fig. 4.

Mesenteric injury and devascularized ileum.

3. Discussion

Seat belts have gone through evolution, with the 3 points “lap and shoulder” retractable seat belt being the latest, most efficient and most commonly manufactured. In literature, the seat belt syndrome is associated mostly with the 2 points restriction “the lap belt”. In both of the previously presented cases, patients were using the 3 points restriction.

Bruising of the anterior abdominal wall is suggested to be due to the belt acting as a fulcrum on the soft muscles of the abdominal wall. It may sometimes result in a complete cut of these muscles, which happened in our second patient. Injury to abdominal viscera has been attributed to compression between the belt and the vertebral column [3], and the intestinal ischemia is primarily due to mesenteric tears [4].

Mesenteric tears usually occur due to the shearing force applied on the mesentery, which happens while the movable intestines continue moving with the same speed of the car, although the car is decelerated by the act of the brakes (described in physics as the inertia) [5]. These tears can be so trivial that a frank intestinal ischemia would not be apparent immediately.

Early diagnosis provides better outcomes for patients with seat belt injuries, but this remains a challenge to trauma surgeons. The abdominal pain in the polytraumatized patients with seat belt syndrome may be dominated by the pain caused by extra-abdominal injuries. Another reason for the delayed diagnosis is that the abdominal pain and tenderness can be attributed to the bruising or injury of the abdominal wall muscles rather than thinking of a serious intra-abdominal injury. The confounding factors such as drug or alcohol intoxication can reduce the reliability of physical examinations. CT scan alone cannot be used to predict the early need of a surgical intervention [6].

A few numbers of cases with delayed presentation of the intra-abdominal injury have been documented in literature. Michael and Rehan [7] reported a case that was without clinical and radiological signs of intraabdominal injuries on presentation and on day three post-injury, developed signs of an acute abdomen and underwent emergency laparotomy which revealed a mesenteric vessel injury and ischemic segment of jejunum. Jones et al. [8] reported that all intra-abdominal injuries following blunt abdominal trauma become clinically apparent within 9 h, and all patients requiring an intervention manifest symptoms or signs within 60 min of arrival.

Abdominal wall ecchymosis (AWE) is associated with abdominal injury in up to 65% of cases (compared to 8% in the absence of AWE) [9]. The typical findings of peritonitis might not be present initially. Repeated examinations of the abdomen are essential since the possibility exists that the peritoneal symptoms can be hidden, especially with children [10]. In suspected cases, repeated CT scans are recommended after 8 h. This can help in the early diagnosis of intestinal injuries [11].

4. Conclusion

Intra-abdominal injury due to seat belt presents characteristically late. The approach to patients with seat belt sign should be with higher index of suspicion of internal organ damage. Those with persistent pain or tenderness despite a negative CT are admitted for observation and repeated examination and abdominal CT.

Consent

Written consent was obtained from both patients for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

No source of funding or sponsor.

Author contribution

Dr. Labib Al-Ozaibi contributed on study design. Dr. Judy Adnan contributed on writing. Dr. Batool Hassan contributed on data collection. Dr. Alya Al-Mazroui contributed on data analysis. Dr. Faisal Al-Badri contributed on review and approval.

References

- 1.Hamilton J.B. Seatbelt injuries. Br. Med. J. 1968;4(November (5629)):485–486. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5629.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gagnier Joel J., Kienle Gunver, Altman Douglas G., Moher David, Sox Harold, Riley David, The CAREGroup The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams R.D. The mechanism of intestinal injury in trauma. J. Trauma Injury Infect. Critical Care. 1963;3(May (3)):288–294. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiken D.W. Intestinal perforation and facial fractures in an automobile accident victim wearing a seat belt. J. La. State Med. Soc. 1963;115(July):235–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macleod J.H., Nicholson D.M. Seat-belt trauma to the abdomen. Can. J. Surg. 1969;12(April (2)):202–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhagvan S., Turai M., Holden A. Predicting hollow viscus injury in blunt abdominal trauma with computed tomography. World J. Surg. 2013;37:123–126. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1798-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodds Michael, Gul Rehan. Noelle cassidy late-diagnosed seat-belt syndrome: a second chance? Inj. Extra. 2006;37:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones E.L., Stovall R.T., Jones T.S. Intra-abdominal injury following blunt trauma becomes clinically apparent within 9 hours. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1020–1023. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandler C.F., Lane J.S., Waxman K.S. Seat-belt sign following blunt trauma is associated with increased incidence of abdominal injury. Am. Surg. 1997;63(10):885–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santschi M., Echavé V., Laflamme S. Seat-belt injuries in children involved in motor vehicle crashes. Can. J. Surg. 2005;48:373–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brofman N., Atri M., Hanson J.M. Evaluation of bowel and mesenteric blunt trauma with multidetector CT. Radiographics. 2006;26:1119–1131. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]