Highlights

-

•

Conservative management alone, in certain cases, can be an effective method of treating large cerebral abscesses that would normally warrant surgical intervention in patients with complex congenital heart conditions.

-

•

Having an alternative, non-surgical, method of treating large brain abscesses in patients with underlying complex congenital heart conditions, in which brain abscesses is a known complication, is of great clinical importance.

-

•

Due to the increasing number of patients living longer with congenital heart conditions, further study into the conservative management of larger abscesses is warranted.

Keywords: Intracerebral abscess, Eisenmenger syndrome

Abstract

Introduction

We present an unusual case where a large intra-cerebral abscess with severe complications was treated successfully with medical management alone in a patient with Eisenmenger syndrome.

Presentation of case

A 40 year old patient with Eisenmenger syndrome presented with a seven day history of headache, neck pain and intermittent vomiting and fever. The only neurological examination finding was blurred vision. MRI revealed a large left occipital lobe abscess, which subsequently ruptured into the lateral ventricle with associated ventriculitis and hydrocephalus. This complicated abscess was successfully treated with intravenous antibiotics alone, with complete resolution of the abscess and hydrocephalus on MRI at 13 months post-diagnosis.

Discussion

Patients with congenital cyanotic heart conditions, like Eisenmenger syndrome, are at increased risk of developing intra-cerebral abscesses. Effectively managing large abscesses with associated intra-ventricular rupture and hydrocephalus in these patients without any form of surgical intervention, including aspiration, is extremely rare.

Conclusion

Patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease who develop large intra-cerebral abscesses with severe complications, which would normally warrant surgical intervention, have the potential to be successfully treated with antibiotics alone with excellent outcome.

1. Introduction

Patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease, like Eisenmenger syndrome, are at an increased risk of developing intra-cerebral abscesses. It is common practice for abscesses larger than 2 cm to undergo some form of surgical intervention, ranging from aspiration to excision of the abscess. However it is rare for large abscesses with associated intra-ventricular rupture and hydrocephalus to be successfully treated with intravenous antibiotics alone.

We present a rare case of a 40 year old patient with Eisenmenger syndrome who developed a 4 cm intra-cerebral abscess with rupture into the lateral ventricle and associated hydrocephalus. The patient was successfully treated with IV antibiotics alone with excellent outcome.

2. Presentation of case

A 40-year-old female with Eisenmenger syndrome, secondary erythrocytosis, and tetralogy of fallot was admitted with a seven day history of headache, neck pain and intermittent vomiting and fever. There was also blurred vision however no visual field defects were detected upon examination. There was no history of seizures or loss of consciousness, and there was no upper or lower limb weakness either in the history or at presentation.

On examination the patient had both central and peripheral cyanosis with a loud P2 ejection systolic murmur at the aortic area and a pansystolic murmur at the tricuspid area. The patient had no speech deficit and her neurological examination, including cranial nerve examination, showed no deficits. Her observations at presentation were GCS 15; blood pressure 120/70; heart rate of 74 and oxygen saturation of 77% (the patient's normal saturations are 70% due to her Eisenmenger syndrome).

The patient's medication at presentation was ferrous sulphate 200 mg OD (once daily), warfarin, amiodarone 200 mg OD, furosemide 20 mg OD, paroxetine 40 mg OD, folic acid 400 micrograms OD, sildenafil 20 mg TDS (three times daily), and co-codamol 30/500 QDS (four times daily).

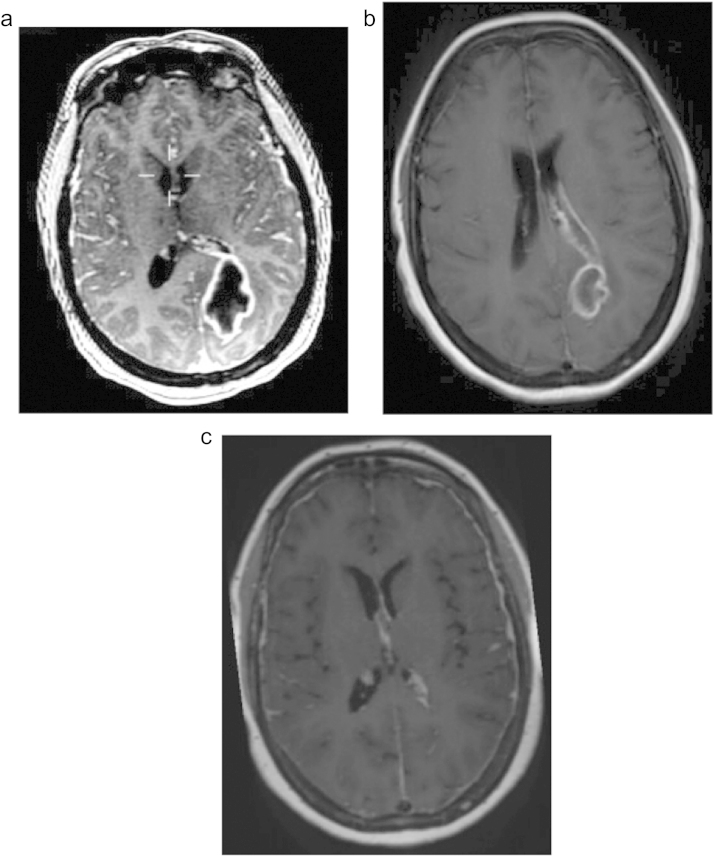

The patient subsequently underwent a CT head with contrast, which showed an intra-cerebral abscess within the left occipital lobe abutting the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle. The abscess measured 40 × 40 mm in the axial plane. A baseline MRI was undertaken on the day of admission, which confirmed the lesion was an abscess (Fig. 1a). The patient was started on ceftriaxone and metronidazole after initial discussion with microbiology. However the patient’s clinical state deteriorated 5 days post admission and a contrast-enhanced MRI was undertaken, which showed rupture of the abscess into the lateral ventricle. It was concluded the abscess had ruptured into the lateral ventricle by the combination of deterioration in the patient’s clinical status and a diffusely enhanced ventricular ependyma with hydrocephalus on the MRI. Following a cardiology and anaesthetic review the patient was deemed unfit for surgery due to her Eisenmenger syndrome and therefore a biopsy of the abscess, surgical evacuation or ventricular drainage was unable to be performed under general anaesthetic.

Fig. 1.

(a) MRI with contrast on day of admission which shows abscess within the left occipital lobe. (b) FLAIR MRI on day 33 post-admission, which shows reduction in abscess size however there is now diffuse enhancement of the lateral ventricular ependyma. (c) MRI with contrast at 13 months post-admission. Note there is complete resolution of the abscess.

Local anaesthetic aspiration or ventricular access device could have been considered as a life saving measure with its own inherent difficulties, including patient positioning. After discussion with microbiology the Ceftriaxone was changed to meropenam, and vancomycin was added. The IV course of meropenam, metronidazole and vancomycin continued for 4 weeks. The patient continued to have intermittent episodes of pyrexia and therefore vancomycin was subsequently switched to linezolid. In addition meropenam was switched to co-amoxiclav. The patient completed 10 weeks of antibiotics as an in-patient and was discharged on co-amoxiclav, linezolid and metronidazole, which she continued for a further 2 weeks. In addition to the day of admission MRI’s were undertaken at 18, 24, 33 and 61 days post-admission. The MRIs, collectively, showed an overall trend of a gradual reduction in the abscess size with an initial enlargement of ventricular involvement (Fig. 1b), followed by a subsequent reduction.

The patient was kept under regular day ward review following discharge. She reported no further episodes of pyrexia, and her follow up MRI at 6 months post- admission showed continued resolution of the abscess and normal ventricular size. The latest follow-up MRI revealed complete resolution of the abscess at 13 months post diagnosis (Fig. 1c).

This work has been reported in line with the CARE criteria (http://www.care-statement.org/).

3. Discussion

Brain abscesses are circumscribed collections of pus within the brain parenchyma, which are formed from a localised area of cerebritis within a well vascularised capsule [1].

The underlying causative agent can be broadly categorised into either bacterial or fungal, with Staphylcoccal agents being the most common organism in patients who have underwent neurosurgery, and Streptococcal agents being the most common in patients who have not underwent neurosurgery [2].

The signs and symptoms depend largely on the specific location of the abscess, with the most common site being the frontal-parietal region and the occipital region being the least common site.

The underlying infection that is responsible for the formation of the abscess can enter the intracranial compartment either directly or indirectly via three routes: contiguous suppurative focus, trauma, or haematogenous spread from a distant focus. Haematogenous spread is the most common route in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease like Eisenmenger syndrome [2].

The type of agent responsible for the abscess depends on the patient's age, site of primary infection, and the underlying condition of their immune system.

The formation of a brain abscess is increased by certain underlying medical conditions including congenital cyanotic heart disease, such as Eisenmenger syndrome [3].

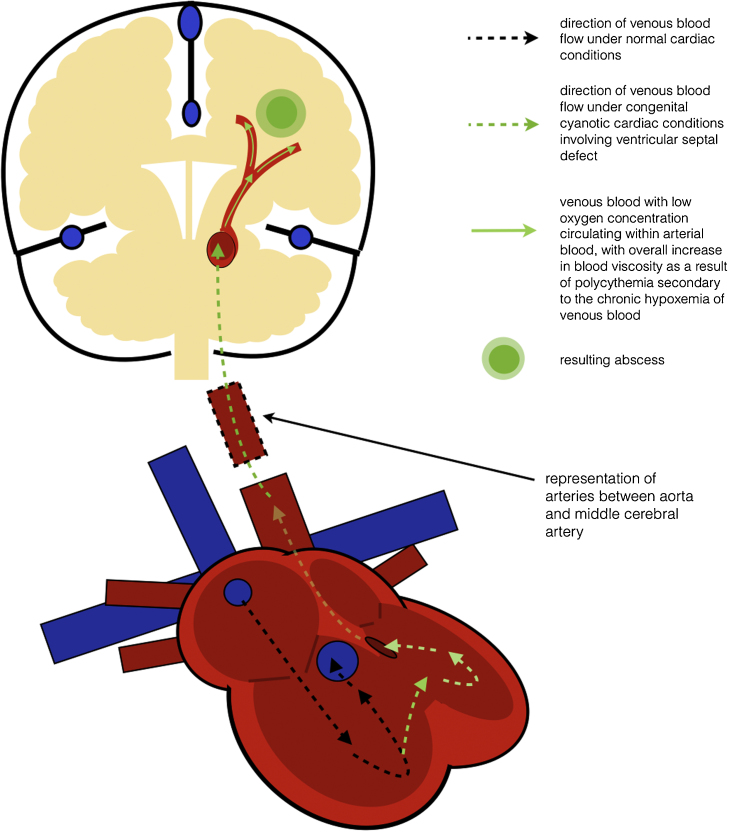

The pathophysiology of brain abscess formation in patients with underlying congenital cyanotic heart disease involves the right-to-left shunting of venous blood (Fig. 2). This shunting allows bacteria within venous blood to by-pass the disinfectant, phagocytic properties of the lungs and travel to the brain [3]. There are two methods by which this process allows bacteria to grow within the cerebral tissue. Firstly, the low oxygen concentration of venous blood results in regions of chronic hypoxemia with resultant secondary polycythemia and metabolic acidosis within the grey–white matter interface of the brain. Secondly, due to the secondary polycythemia the blood becomes more viscous, which coupled with the chronic hypoxemia of the shunted venous blood, creates a suitable microenvironment for microrganisms to grow. These two methods are also thought to be responsible for the coagulopathies seen in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease.

Fig. 2.

Pathophysiology of how brain abscesses form in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease involving ventricular septal defects.

Although brain abscesses can be treated by medical or surgical intervention, or by a combination of both, it is common practice for abscesses larger than 2 cm to undergo surgical intervention. The patient used in this report had a 4 cm abscess, with rupture of the abscess into the lateral ventricle resulting in ventriculitis and hydrocephalus—features that normally warrant surgical intervention [4]. However after both a cardiology and anaesthetic review the patient was deemed unfit for any surgical intervention, including aspiration of the abscess for specimen culture, due to her underlying Eisenmenger syndrome which is responsible for the patients baseline oxygen saturations of 70%.

The incidence of brain abscesses in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease is relatively rare (12.8–69.4% of published cases) [5], [6]. This case report provides clinicians who are presented with similar cases with a non-invasive management option for this rare condition, for which there are currently no conclusive guidelines.

This is of particular importance in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease because of the inherent anaesthetic and haemorrhagic risks associated with these patients, including the formation of intra-capsular hematomas, which can occur even with the less invasive surgical interventions such as aspiration [7].

4. Conclusion

The use of serial imaging and IV antibiotics alone in a patient with a cyanotic heart condition who develops a large cerebral abscess with intra-ventricular rupture and hydrocephalus, which would normally warrant surgical intervention, can result in both complete clinical and radiological resolution of the abscess. Although the management used in this case report is not new, its use in an abscess of this size with intra-ventricular rupture and hydrocephalus, along with the associated excellent outcome, is extremely rare.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no declaration of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contribution

Allan Hall has written, reviewed and submitted the article. Mark White critically reviewed the article and obtained the images. Pasquale Gallo critically reviewed the article and was the senior consultant in charge of the case.

Guarantor

Allan Hall and Mark A.J. White.

References

- 1.Miranda H.A., Leones S.M.C., Elzain M.A., Moscote-Salazar L.F. Brain abscess: current management. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2003;4(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.116472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathisen G.E., Johnson J.P. Brain abscess. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997;25(4):763–779. doi: 10.1086/515541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeshita M., Kagawa M., Yato S., Izawa M., Onda H., Takakura A. Current treatment of brain abscess in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1270–1279. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeshita M., Kawamata T., Izawa M., Hori T. Prodromal signs and clinical factors influencing outcome in patients with intraventricular rupture of purulent brain abscess. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(2):310–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moorthy R.K., Rajshekhar V. Management of brain abscess: an overview. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008;24 doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/6/E3. E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chau A.M., Xu L.L., Fairhall J.M., Chaganti J., McMullan B.J. Brain abscess due to propionibacterium propionicum in Eisenmenger syndrome. Med. J. Aust. 2012;196(8):525–526. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arlotti M., Grossi P., Pea F., Tomei G., Vullo G., De Rosa F.G. Consensus document on controversial issues for the treatment of infections of the central nervous system: bacterial brain abscesses. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;14(October, Suppl. 4):S79–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]