Abstract

Mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 transcription factors (HNF1α/β) are associated with diabetes. These factors are well studied in the liver, pancreas and kidney, where they direct tissue-specific gene regulation. However, they also have an important role in the biology of many other tissues, including the intestine. We investigated the transcriptional network governed by HNF1 in an intestinal epithelial cell line (Caco2). We used chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by direct sequencing (ChIP-seq) to identify HNF1 binding sites genome-wide. Direct targets of HNF1 were validated using conventional ChIP assays and confirmed by siRNA-mediated depletion of HNF1, followed by RT-qPCR. Gene ontology process enrichment analysis of the HNF1 targets identified multiple processes with a role in intestinal epithelial cell function, including properties of the cell membrane, cellular response to hormones, and regulation of biosynthetic processes. Approximately 50% of HNF1 binding sites were also occupied by other members of the intestinal transcriptional network, including hepatocyte nuclear factor 4A (HNF4A), caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2), and forkhead box A2 (FOXA2). Depletion of HNF1 in Caco2 cells increases FOXA2 abundance and decreases levels of CDX2, illustrating the coordinated activities of the network. These data suggest that HNF1 plays an important role in regulating intestinal epithelial cell function, both directly and through interactions with other intestinal transcription factors.

Keywords: HNF1, intestinal epithelium, transcriptional network, glucose transport

Introduction

The key properties of the epithelium lining the intestine are the absorption of nutrients, solutes and water, together with maintenance of a protective barrier against microorganisms and noxious substances. There is substantial functional diversity within the epithelium from the proximal (small) intestine to the distal (colon) regions and among cell types along the crypt-villus axis. The crypt-villus units encompass several differentiated cell types including enterocytes, enteroendocrine, goblet and Paneth cells (1). A unique feature of the intestinal epithelium is its constant renewal controlled by the coordinated proliferation and differentiation of epithelial stem cells and progenitor cells in the base of the crypt (2). The highly dynamic status of the epithelium is regulated by a transcriptional network, which controls signaling pathways (3, 4), the abundance of critical proteins for solute and ion transport, and the absorption of nutrients (5-7). This network includes hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha and beta (HNF1α/β), caudal-type homeobox 2 (CDX2), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4α), and GATA family factors (8-11).

HNF1α and HNF1β are very similar within both their dimerization- and DNA-binding domains, and they can bind as homo- or hetero-dimers to the same DNA motif (12, 13). HNF1α was originally identified as a transcription factor (TF) critical for liver-specific gene transcription (14). However, both HNF1α and HNF1β were subsequently detected in other organ sites, including the pancreas, kidney, and digestive tract (15, 16). The HNF1 factors are implicated in several types of diabetes. Mutations in both HNF1α and HNF1β may cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) a monogenic form of diabetes (17, 18). More recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified genetic variants within or close to the HNF1α and HNF1β genes that associated with late onset type 2 diabetes (19-22). The role of HNF1 in coordinating gene expression in the pancreas and kidney is well studied. Dominant mutations in HNF1α cause progressive impairment of β-cell function in the pancreas (23, 24). Moreover, HNF1α drives highly tissue-specific transcriptional programs with markedly different effects of Hnf1α deficiency evident in mouse pancreatic islets and liver (25). Liver dysfunction in Hnf1α knockout mice is largely due to decreased enzyme production, while kidney phenotypes of glycosuria/phosphaturia result from insufficient transport proteins in the renal proximal tubule (26-28).

In contrast to the in depth analyses of the role of HNF1α/β in the pancreas and liver, much less is known about the function of these TFs in the intestine, though cooperation between HNF1, CDX2 and GATA4 is known to promote intestinal cell differentiation (29). Studies of HNF1 targets in the human intestine to date are mainly focused on individual loci rather than pathways of differentiated function and include several metabolic genes (6, 30). Disruption of the mouse Hnf1α gene impacts barrier function, glucose transport, cell proliferation and differentiation of the intestinal epithelium (10), though the HNF1 target genes responsible for these defects are unknown. Glucose absorption is an important function of the intestinal epithelium and is particularly relevant to the HNF1 transcriptional network in this tissue, due to the association between HNF1 and diabetes. However, very little is known about how HNF1 affects intestinal glucose transport. Two distinct families of glucose transporters are located on the apical membrane of enterocytes: the facilitative diffusion glucose transporters (GLUTs), and the Na+/glucose cotransporters (SGLTs) (31, 32). HNF1α directly regulates SLC2A2 (GLUT2) expression in mouse pancreatic β-cells (33), and SGLT2 in kidney (27).

One powerful way of revealing the transcriptional network coordinated by a specific factor in differentiated cell types is to generate data on its genome-wide binding profile. Here we use chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq), to map the HNF1 binding sites genome-wide in differentiated Caco2 cells. Post-confluent Caco2 cells have many similarities with mature absorptive enterocytes (34, 35). It is likely that since Caco2 is a colon carcinoma line it also exhibits aspects of a cancer-related genomic signature, though a comparison of with normal primary intestinal epithelial cells, was not a focus of this study. We show that the majority of HNF1 binding sites are located in intergenic and intronic regions of the genome. These data add substantially to previous analyses of HNF1 regulation of many individual genes, which generally examined HNF1-binding elements in the gene promoters. Moreover, by comparing this HNF1 dataset with CDX2 and HNF4α ChIP-seq data in Caco2 cells (36), we observed auto- and cross-regulatory circuits for these factors. Finally, we show that the solute carrier family 2, member 2 (SLC2A2) gene, which encodes the facilitated glucose transporter SLC2A2/GLUT2, is a direct target of HNF1 in human intestinal cells. Our data provide insights into how HNF1 exerts its regulatory functions in a specific cell type and may contribute to the intestinal phenotype of diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transient siRNA knockdown

The human colon carcinoma cell line Caco2 was grown in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium) supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum). All data were generated using cells that were at least 48h post-confluent. For siRNA double knockdown of HNF1α and HNF1β, Caco2 cells were reverse-transfected with LipofectamineTM RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A mixture of 20nM each of HNF1α (sc-35567) and HNF1β siRNA (sc-37928) or 40nM control siRNA (sc-37007) was used (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology [SCB]). Whole cell lysate and RNA were extracted 48 hr post-transfection.

ChIP-seq

Chromatin from Caco2 cells was prepared as described previously (37) with modifications. Two independent experiments were performed. Sonicated chromatin was incubated with Protein A beads (Dynabeads, Life Technology [LT]) coupled to 10μg rabbit anti-HNF1 antibody (SCB, sc-8986x) overnight at 4°C. Input DNA was also prepared for both replicates and used to provide background signal intensity. ChIP DNA purification and library construction used protocols reported previously (38). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hi-Seq 2000 machine. Fastq files were aligned to human genome hg19 using Bowtie (v 1.0.0) with a seed length of 40 and a maximum number of 3 mismatches allowed in the seed. Only uniquely mapped reads were included in further analysis. Homer software (39) was used to generate tag directories and peaks were called with a 0.1% false discovery rate (FDR). ChIP-seq data are deposited at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/GSE 67740. Homer was also used for de novo motif finding within a 200bp window centered on identified peaks, unless otherwise specified.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed by standard protocols, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE and quantitated by western blot. Antibodies used were against HNF1 (sc-8986), FOXA2 (sc-6554), HNF4A (sc-8987) all from SCB, also CDX2 (Bethyl Laboratories, A300-692A), SLC2A2 (Millipore, 07-1402), GATA4 (Abcam, ab61767), and β-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, T4026). Protein quantification was performed using Image J software (NIH) (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

qRT-PCR (quantitative reverse transcription-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and cDNA was made from total RNA by using the Taqman reverse-transcription reagents (LT, N8080234). Gene expression was measured using SYBR green PCR master mix (LT, 4367659) and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1).

Glucose uptake assays

48 hr after HNF1α/β or control siRNA transfection, Caco2 cells were treated with either vehicle control (PBS) or 100μM 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl) amino]-2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-NBDG), a fluorescent glucose mimic (Life Technologies, N13195) for 2h. Cells were then analyzed by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Ten thousand events were recorded for each condition.

Results

Genome-wide HNF1 occupancy defined by ChIP-seq

HNF1α and β occupancy genome wide was mapped by ChIP-seq in 3 days post-confluent Caco2 cells. We showed previously that the antibody used was effective in conventional ChIP experiments (40, 41), and although it detects both HNF1α and β, the former is much more abundant in Caco2 cells [40], so these data largely reflect the binding sites for HNF1α. Two independent biological replicas were analyzed and peak calling, annotation, and motif analysis was performed using the Homer software package (39). Applying a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.1%, 5060 and 4955 peaks were called in the two biological replica experiments. Among these peaks, 2906 overlapped between the replicas and were included in further analysis.

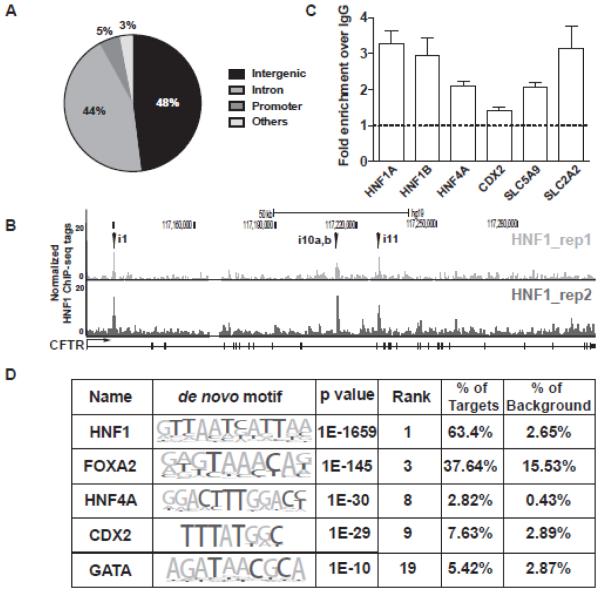

The distribution of HNF1 peaks in the genome is shown in Fig. 1A, where 48% and 44% respectively, of the 2906 are located in intergenic or intron regions. The remaining 8% of peaks are found in promoters (defined as −1kb to +100bp with respect the transcription start site of genes) or in other genomic regions (untranslated regions (UTRs) and exons). The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene provided a positive control for the ChIP-seq experiment, since we identified HNF1 binding sites in introns 1, 10, and 11 of the gene previously (40-42) (Fig. 1B). Several HNF1 binding sites were chosen for further validation of the ChIP-seq data, including peaks within HNF1α, HNF1β and SLC2A2 (all intronic), CDX2 (10kb downstream) and HNF4A and solute carrier family 5 (sodium/sugar cotransporter) member A9 (SLC5A9) (both promoter). Conventional ChIP was performed using the same protocol as for the ChIP-seq experiment and > 2 fold enrichment of HNF1 was seen for all loci tested except CDX2 (Fig. 1C). To test whether HNF1-bound genes were also regulated by HNF1, we used RNA extracted from Caco2 cells in which HNF1 was depleted by specific siRNAs or non-targeting siRNA-treated control cells. The expression level of genes that are involved in transporter activity and the immune response and have HNF1 peaks within 20kb of their gene body were assayed by RT-qPCR (Suppl. Fig. 1). Four of the 5 genes tested were downregulated significantly after HNF1 depletion.

Figure 1. Characterization of genome-wide HNF1 binding in differentiated Caco2 cells.

(A) Pie chart showing the percentage of peak distribution in intergenic, intron, promoter, and other regions. (B) UCSC genome browser image showing HNF1 ChIP-seq peaks in the CFTR gene region (marked by arrowheads). (C) Validation of HNF1 target genes identified by the ChIP-seq data. Results are the mean of 3 independent experiments with error bars showing S.E.M. (D) Homer de novo motif analysis for HNF1 binding sites. The nucleotide frequencies of the genomic sequences aligned at the motif are shown in a sequence logo representation (63). The percentages of motif incidence in target and background regions are also listed.

De novo motif analysis (Homer) of the 2906 HNF1 ChIP-seq peaks was then performed to determine the enrichment of TF binding sites. The HNF1 binding motif was the most significantly enriched motif (P = 1e−1659) and ~63% of all peaks contained this motif (Fig. 1D). Also enriched were binding motifs for forkhead box A2 (FOXA2), HNF4 and CDX2, (P = 1e−145/−30/−29) respectively (Fig. 1D). A complete list of the de novo motifs identified is shown in Supplementary Table 2. These findings suggest that our HNF1 ChIP-seq data are robust and also that the other TFs identified could be involved in HNF1-mediated transcriptional regulation.

HNF1 cooperates with other transcription factors to form a transcriptional regulatory network

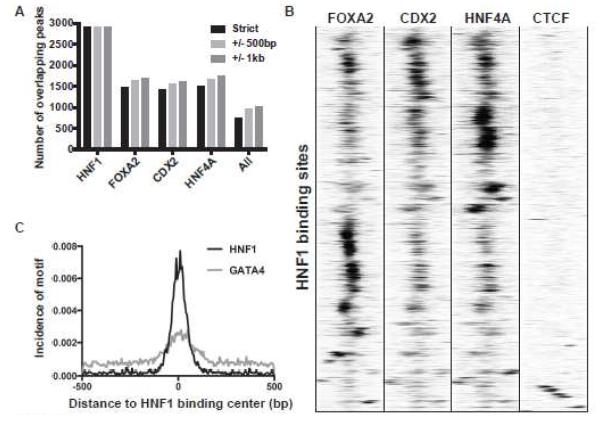

Since binding motifs for other intestinal transcription factor were identified within the HNF1 ChIP-seq peaks (Fig. 1D), we next investigated whether HNF1 cooperated with other factors at these sites. We performed replica FOXA2 ChIP-seq experiments in Caco2 cells (43) (GEO:GSE66218) and utilized the Caco2 CDX2 and HNF4A ChIP-seq data published by Verzi et al. (36) (GEO:GSE23436). All data sets were processed with the same pipeline. We then intersected the FOXA2, CDX2, HNF4A and HNF1 ChIP-seq data sets using 3 different criteria: ChIP-seq peaks 1) have at least 1bp overlap with HNF1 peaks (strict); 2) are located within 500bp of HNF1 peaks (+/− 500bp); 3) map to within 1kb of HNF1 peaks (+/− 1kb) (Fig. 2A). With the strict criterion, out of 2906 HNF1 ChIP-seq peaks, 1495 are occupied by HNF4A, 1420 by CDX2, and 1472 by FOXA2. A total of 748 peaks are occupied by all four factors. Relaxing the HNF1 peak overlap criteria (+/− 500bp and +/− 1kb), identified only a small number of additional peaks for the other factors (Fig. 2A), suggesting the binding sites for all 4 factors are in close proximity. Next, we plotted the ChIP-seq signals of these factors in the +/− 500bp region surrounding the center of all HNF1 binding sites (Fig. 2B). The heatmap shows that ChIP signals from FOXA2, CDX2, and HNF4A are enriched near HNF1 peaks with very similar patterns, indicating that these factors may interact as part of a single complex. CTCF ChIP signals (ENCODE data) provided a negative control and did not show co-localization with the intestinal TFs. The GATA motif is also enriched in the HNF1 peaks in Caco2 cells (Fig.1D). Both GATA4 and GATA6 are expressed in these cells (reviewed in (11)). However, there are no genome-wide data for GATA4, so instead we analyzed the GATA motif density near HNF1 binding sites (Fig. 2C). These results show enrichment of the GATA motif near HNF1 sites, suggesting that GATA4 or GATA6 may also cooperate with HNF1 and function to fine-tune gene expression.

Figure 2. Crosstalk between HNF1 and other transcription factors.

(A) Bar graph showing the number of overlapping peaks between HNF1 and other factors with different stringencies as indicated in the figure. (B) Heatmap scale indicates normalized ChIP-seq tag counts of FOXA1, CDX2, HNF4A, and CTCF near HNF1 binding sites. Each row of the heatmap represents a 1kb genomic window centered at an HNF1 binding peak summit. (C) Histogram showing GATA4 motif density near HNF1 binding sites. Motif density is calculated for each HNF1 peak and averaged before plotting across a +/− 500bp region centered on the HNF1 binding peak similar to (B).

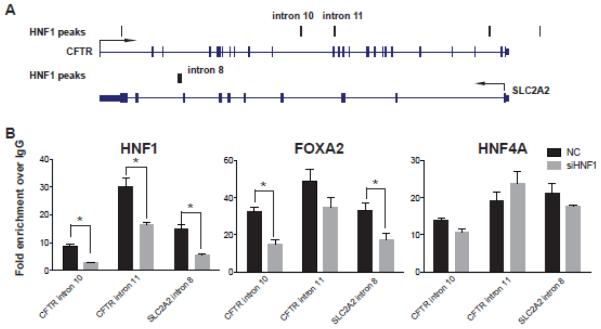

To investigate further whether HNF1, FOXA2, and HNF4A bind cooperatively to DNA, we depleted HNF1α/β in Caco2 cells and then performed ChIP with antibodies specific to each factor. CFTR is regulated primarily by distal cis-acting enhancers, which are recruited to the promoter by specific transcription factors (44), (45); (40-43), (reviewed in (46)). Figure 3A shows the sites of HNF1 occupancy that were tested at cis-regulatory elements in CFTR introns 10 and 11 and in SLC2A2 intron 8. As expected, HNF1α/β depletion significantly reduced occupancy of these factors at all sites tested (Fig. 3B). FOXA2 enrichment also decreased significantly after HNF1α/β loss at peaks in CFTR (intron 10) and SLC2A2 (intron 8), suggesting that HNF1 may stabilize bound FOXA2. HNF4 enrichment was unchanged after HNF1α/β depletion at all 3 loci tested.

Figure 3. Cooperative binding of HNF1, FOXA2 and HNF4A.

(A) Diagrams show HNF1 binding sites at the CFTR and SLC2A2 gene loci. (B) ChIP data showing enrichment of HNF1, FOXA2, and HNF4A at selected sites in negative control (NC) and HNF1 depleted (siHNF1) Caco2 cells. n=3, *p<0.05.

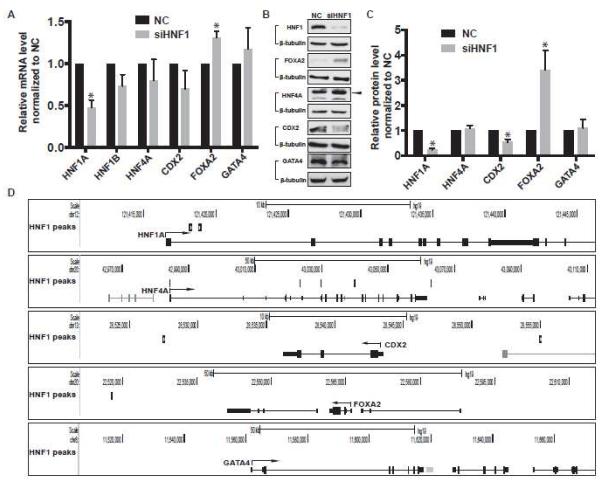

To determine whether there is transcriptional cross-talk between HNF1, FOXA2, CDX2, HNF4A, and GATA4, we depleted both HNF1α/β and measured the impact on expression of the other genes by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4A). HNF1α transcript levels decreased significantly demonstrating efficient siRNA–mediated depletion. HNF1β transcript levels were not significantly altered, likely due to the very low endogenous level of HNF1β in Caco2 cells. We observed a significant increase in FOXA2 mRNA levels, but changes in abundance of HNF4A, CDX2 and GATA4 did not reach statistical significance. Next, TF proteins were measured by western blot after HNF1α/β depletion (Fig. 4B). Though HNF4A and GATA4 levels were not altered, CDX2 significantly decreased and FOXA2 increased (p<0.05) (Fig. 4B, 4C). A search for HNF1 ChIP-seq peaks at the HNF1α/β, HNF4A, CDX2, FOXA2 and GATA4 loci (Fig, 4D) revealed intronic peaks in HNF1α and HNF4A. In contrast the nearest sites of HNF1 occupancy were 10 kb upstream and ~15 kb downstream of the CDX2 gene and ~40 kb 3’ to the FOXA2 locus. Thus the impact of HNF1 on FOXA2 expression may not be direct. No HNF1 peaks were found near the GATA4 gene. Together, these data suggest that HNF1α/β, HNF4α, and CDX2 may generate an auto- and cross-regulatory network and cooperate to regulate gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells.

Figure 4. HNF1 regulates the expression levels of its co-factors.

(A) RT-qPCR data showing the mRNA levels of transcription factors in HNF1α/β knockdown (siHNF1) Caco2 cells relative to negative control (NC) cells. Data are normalized to β2 microglobulin (β2M) and with NC set to 1. n=3, *p<0.05. (B) Western blots showing the protein levels of transcription factors in NC and HNF1α/β knockdown (siHNF1) Caco2 cells with β-tubulin as loading control. (C) Quantification of the western blots by densitometry, TFs normalized to β-tubulin with NC set to 1. n=3, *p<0.05. (D) UCSC genome browser image showing the HNF1 peaks near the gene bodies of other TFs.

HNF1 is involved in multiple biological pathways important for intestinal epithelial function

Next, the nearest gene annotation method (39) was used to predict genes that might be regulated by HNF1 occupancy of a cis-regulatory element. Though this method has an inherent weakness, since critical cis-elements may be at considerable genomic distances from the genes they control, it still has value in the absence of better analytical tools. Each HNF1 binding site was assigned to the nearest transcriptional start site (TSS) to generate a nearest gene list (Supplementary Table 3). The genes in this list were then used for a gene ontology process enrichment analysis using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (47, 48). The ten most enriched processes are shown in Table 1 and the complete output, together with the genes that are associated with each enriched process, are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 1.

Ten most enriched gene ontology terms generated by DAVID using genes with HNF1 peaks close to their promoters.

| GO terms | P value |

|---|---|

| GO:0044459~plasma membrane part | 2.35E-11 |

| GO:0048545~response to steroid hormone stimulus | 1.67E-08 |

| GO:0051270~regulation of cell motion | 1.98E-08 |

| GO:0031328~positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process |

6.59E-08 |

| GO:0009891~positive regulation of biosynthetic process | 7.87E-08 |

| GO:0009725~response to hormone stimulus | 1.00E-07 |

| GO:0009719~response to endogenous stimulus | 1.24E-07 |

| GO:0010557~positive regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process |

1.25E-07 |

| GO:0001822~kidney development | 1.42E-07 |

| GO:0000902~cell morphogenesis | 1.44E-07 |

The GO process with the most significant P-value is plasma membrane part (GO:0044459, P=2.35E-11), which includes genes encoding proteins with diverse functions at the cell membrane. These comprise cell junction proteins and proteins with roles in cell adhesion and transmembrane transport. Several catenin and claudin genes, which play an important role in the defensive barrier function of the intestinal epithelium, have HNF1 binding sites within 10 kb flanking the gene or in introns (Supplementary Fig. 2). Multiple genes encoding ion- or small molecule transporters required for intestinal absorption of nutrients, electrolytes and water also had HNF1 occupancy within introns or near to their TSS (Supplementary Fig. 2). These include chloride channel, voltage-sensitive 3 (CLCN3), potassium channel, subfamily K, member 5 (KCNK5), SLC4A4 (sodium/bicarbonate cotransporter), and SLC2A2 (GLUT2, glucose tranporter) (Fig. 5C).

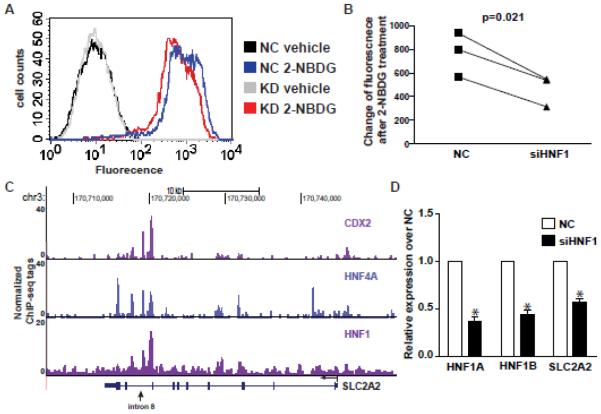

Figure 5. HNF1 modulates glucose transport in Caco2 cells.

(A) Glucose uptake represented by FACS data showing fluorescence distribution of control and HNF1 depleted (KD) Caco2 cells treated with either vehicle control or 2-NBDG. (B) Quantification of 3 biological replicates of FACS results. Paired t-test was used to calculate the p-value. (C) UCSC genome browser image showing HNF1, HNF4A and CDX2 binding sites in the SLC2A2 gene body. (D) RT-qPCR data showing the mRNA levels of HNF1α, HNF1β, and SLC2A2 gene in HNF1 knockdown (siHNF1) Caco2 cells relative to negative control (NC) cells. Data are normalized to β2 microglobulin (β2M) and with NC set to 1. n=4, *p<0.05.

Another highly significant GO process was response to hormone stimulus (GO:0009725, P=1.00E-7), reflecting the important role of hormone-regulated metabolic processes in intestinal biology. The insulin receptor substrate 1 and 2 genes (IRS1/2) are both included in this process and have a pivotal role in response to insulin and glucose homeostasis (49, 50). IRS1 shows HNF1 occupancy at multiple intronic sites and within the 3’UTR (Suppl. Fig2.). Due to the well-established link between HNF1 and diabetes, and the association of HNF1 and genes involved in glucose homeostasis revealed by our ChIP-seq data, we asked whether HNF1 has a role in glucose transport in intestinal epithelial cells. Again using post-confluent Caco2 cells, we monitored the rate of glucose uptake using a fluorescent glucose analog 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl) amino]-2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-NBDG). Cells were transfected with either siRNAs specific for HNF1α and HNF1β together, or with a negative control siRNA. After 48h, 100μM 2-NBDG was added to the cells and intracellular fluorescence was measured by FACS 2h after the treatment. One representative experiment is shown in Fig. 5A, where the red trace (representing the knockdown cells) shifts leftward when compared to the negative control siRNA-transfected cells (blue trace), corresponding to a reduction in glucose uptake. Quantification of the FACS data showed that the decrease in glucose uptake after HNF1 depletion was significant (Fig. 5B, paired t test, p<0.05). Among the potential HNF1 target genes, SLC2A2, which encodes the facilitated glucose transporter SLC2A2 (GLUT2), was a plausible candidate to explain the reduced glucose uptake after HNF1 depletion. This transporter is abundant in the intestine (51) and where it is known to be critical for glucose transport (reviewed in (52)). Within the SLC2A2 gene a cluster of HNF1-bound peaks is seen in intron 8, which overlaps with sites of both CDX2 and HNF4A occupancy (Fig. 5C), suggesting these TFs have a role in its regulation. This cluster of intronic TF binding sites may correspond to an enhancer element that interacts with the SLC2A2 gene promoter by a looping mechanism, similar to that we described previously at the CFTR locus (44). Verification of the intron 8 HNF1 binding in SLC2A2 by conventional ChIP is shown in Fig. 1C. Moreover, HNF1 depletion in Caco2 cells significantly reduced SLC2A2 mRNA levels as measured by RT-qPCR (Fig. 5D).

Positive regulation of biosynthetic processes (GO:0009891, P=7.87E-8), which includes many transcription factors, also has a very high P-value and may reflect the role of HNF1 as a central regulator of the intestinal transcriptional network. The regulatory network coordinating HNF1 and CDX2, HNF4A, and FOXA2 was examined in Fig. 2-4. Among other HNF1-bound TF genes are Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARG), which are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Discussion

HNF1 was originally identified as a liver specific transcription factor (53) though it soon became clear that this factor had an important role in tissue specific gene expression in many other tissues. The discovery of mutations in HNF1 in diabetes led to extensive characterization of its functions in pancreas and kidney. In comparison, HNF1 function in intestine has received less attention. However, HNF1 is abundant in the intestinal epithelium, where it directs critical transcriptional programs (29, 30). HNF1 is known to cooperate with CDX2 to activate the differentiation program of human intestinal epithelial cells, while GATA4 may drive morphological change (29). Though promoter occupancy by HNF1 (shown by conventional ChIP) is known to contribute to intestinal expression of a number of individual genes, there are currently no genome-wide (ChIP-seq) data for this factor in human intestinal epithelial cells. Here we report HNF1 ChIP-seq data in post-confluent Caco2 cells, which identified 2907 binding sites with high confidence. Among these were ChIP-seq peaks at the promoters of genes that were previously shown to be regulated by HNF1, including sucrose-isomaltase (SI) (30), fibrinogen α chain and β chain (FGA and FGB), and serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (SERPINA 1) (53). However, our genome-wide data showed that promoter bound HNF1 only comprises ~5% of the total binding events. The majority of cis-regulatory elements that recruit this factor are intergenic and intronic and thus may have been overlooked in previous studies. Consistent with these observations are our previous data showing the important role of HNF1 recruitment to intronic elements in regulating CFTR gene expression (40, 41). These genome-wide data facilitate investigation of the transcriptional network that includes HNF1 and the specific pathways and genes that it controls.

Within the transcriptional network in the intestinal epithelium multiple TFs cooperate to coordinate gene expression patterns. It is known from single locus and phenotypic studies that HNF1, CDX2, FOXA2, HNF4 and GATA4 are pivotal to this network (29, 30, 40). FOXA2 and HNF1 are both activators of the CFTR gene (40). We showed previously that HNF1 depletion had no effect on CFTR mRNA abundance in Caco2 cells, while depletion of FOXA2 had a dramatic repressive effect, (40). This observation is consistent with data in the current manuscript showing increased FOXA2 expression after HNF1 knockdown. HNF1 was shown previously to interact with CDX2 and GATA4 at gene promoters (6, 30). Also, HNF1, CDX2, and GATA4 function together to drive enterocyte differentiation (29). GATA4 also interacts with CDX2 and HNF1α to regulate the SI gene (30). FOXA2 ChIP-seq data in mouse liver further suggest that the HNF1 motif is enriched around FOXA2 peaks (54). Combining CDX2 and HNF4A ChIP-seq data generated by others (36), with our FOXA2 data (43), we demonstrate that HNF1 co-occupies the same genomic regions as these factors in intestinal epithelial cells. This observation provides compelling evidence that intestinal gene expression is regulated cooperatively by these factors.

We found that not only does HNF1 cooperate with these TFs, it also impacts the expression of FOXA2 and CDX2. FOXA2 is characterized as a pioneer factor because of its ability to bind to condensed chromatin and remodel it for other factors to bind (55). CDX2 is exclusively expressed in intestinal epithelium (56) and behaves as a master regulator of intestinal fate. CDX2 levels decreased in Hnf1α/β −/− double mutant mice and a novel HNF1 binding site was observed 10kb upstream of the CDX2 promoter (57), which is also evident in our data. Mutations in both HNF4A and HNF1 are associated with MODY (18, 58) and cause similar diabetic phenotypes, suggesting they may be functionally linked. In summary, our data show that HNF1 forms a complex transcriptional network with CDX2, HNF4A, and FOXA2 to regulate intestinal gene expression.

Glucose absorption in small intestine is crucial for glucose homeostasis. Since HNF1 is associated with diabetes, we asked whether this factor regulated genes involved in glucose transport. We determined that depletion of HNF1 impaired glucose absorption in Caco2 cells. SLC2A2 encodes the facilitative diffusion glucose transporter SLC2A2, which is critical for glucose uptake in the apical membrane of intestinal epithelium (52). Furthermore, an intronic SNP in the SLC2A2 gene is associated with high fasting glucose level in an eQTL study (59). However, several other glucose transporter genes are also candidates for regulation by HNF1 since SLC2A2, SLC2A8, SLC2A9, and SLC5A2 all have HNF1 binding sites nearby or within them. SLC2A8 is predominantly expressed in the testis (60), SLC2A9 is most highly expressed in kidney and liver (61) while SLC5A2 is also abundant in the kidney (62). Our data show SLC2A2, SLC2A8 and SLC5A2 are all expressed in Caco2 cells although SLC2A2 and SLC5A2 transcripts are relatively more abundant. It is likely that HNF1 targets multiple genes in the intestinal epithelium to exert its effects on glucose absorption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Jorge Ferrer and Dr. S-H Leir for helpful suggestions.

Grants

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01HD068901 (PI:AH) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Harris11G0 and Harris14PO).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Shroyer NF. In: Anotomy and physiology of the small and large intestines. Wyllie R, Hyams J, Kay M, editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2011. S.A. K. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heath JP. Epithelial cell migration in the intestine. Cell biology international. 1996;20(2):139–46. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen J, Pedersen EE, Galante P, Hald J, Heller RS, Ishibashi M, et al. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1. Nature genetics. 2000;24(1):36–44. doi: 10.1038/71657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura T, Tsuchiya K, Watanabe M. Crosstalk between Wnt and Notch signaling in intestinal epithelial cell fate decision. Journal of gastroenterology. 2007;42(9):705–10. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma L, Juttner M, Kullak-Ublick GA, Eloranta JJ. Regulation of the gene encoding the intestinal bile acid transporter ASBT by the caudal-type homeobox proteins CDX1 and CDX2. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302(1):G123–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00102.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchelmore C, Troelsen JT, Spodsberg N, Sjostrom H, Noren O. Interaction between the homeodomain proteins Cdx2 and HNF1alpha mediates expression of the lactase-phlorizin hydrolase gene. The Biochemical journal. 2000;346:529–35. Pt 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Wering HM, Huibregtse IL, van der Zwan SM, de Bie MS, Dowling LN, Boudreau F, et al. Physical interaction between GATA-5 and hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha results in synergistic activation of the human lactase-phlorizin hydrolase promoter. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(31):27659–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattin AL, Le Beyec J, Barreau F, Saint-Just S, Houllier A, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha, a key factor for homeostasis, cell architecture, and barrier function of the adult intestinal epithelium. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29(23):6294–308. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00939-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao N, White P, Kaestner KH. Establishment of intestinal identity and epithelial-mesenchymal signaling by Cdx2. Developmental cell. 2009;16(4):588–99. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lussier CR, Brial F, Roy SA, Langlois MJ, Verdu EF, Rivard N, et al. Loss of hepatocyte-nuclear-factor-1alpha impacts on adult mouse intestinal epithelial cell growth and cell lineages differentiation. PloS one. 2010;5(8):e12378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molkentin JD. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(50):38949–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Simone V, De Magistris L, Lazzaro D, Gerstner J, Monaci P, Nicosia A, et al. LFB3, a heterodimer-forming homeoprotein of the LFB1 family, is expressed in specialized epithelia. The EMBO journal. 1991;10(6):1435–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rey-Campos J, Chouard T, Yaniv M, Cereghini S. vHNF1 is a homeoprotein that activates transcription and forms heterodimers with HNF1. The EMBO journal. 1991;10(6):1445–57. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frain M, Swart G, Monaci P, Nicosia A, Stampfli S, Frank R, et al. The liver-specific transcription factor LF-B1 contains a highly diverged homeobox DNA binding domain. Cell. 1989;59(1):145–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumenfeld M, Maury M, Chouard T, Yaniv M, Condamine H. Hepatic nuclear factor 1 (HNF1) shows a wider distribution than products of its known target genes in developing mouse. Development. 1991;113(2):589–99. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffinier C, Barra J, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Expression of the vHNF1/HNF1beta homeoprotein gene during mouse organogenesis. Mechanisms of development. 1999;89(1-2):211–3. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horikawa Y, Iwasaki N, Hara M, Furuta H, Hinokio Y, Cockburn BN, et al. Mutation in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene (TCF2) associated with MODY. Nature genetics. 1997;17(4):384–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamagata K, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, Menzel S, Furuta H, Vaxillaire M, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY3) Nature. 1996;384(6608):455–8. doi: 10.1038/384455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Dina C, Welch RP, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nature genetics. 2010;42(7):579–89. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weedon MN, Owen KR, Shields B, Hitman G, Walker M, McCarthy MI, et al. A large-scale association analysis of common variation of the HNF1alpha gene with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Caucasian population. Diabetes. 2005;54(8):2487–91. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winckler W, Burtt NP, Holmkvist J, Cervin C, de Bakker PI, Sun M, et al. Association of common variation in the HNF1alpha gene region with risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(8):2336–42. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winckler W, Weedon MN, Graham RR, McCarroll SA, Purcell S, Almgren P, et al. Evaluation of common variants in the six known maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) genes for association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):685–93. doi: 10.2337/db06-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrne MM, Sturis J, Menzel S, Yamagata K, Fajans SS, Dronsfield MJ, et al. Altered insulin secretory responses to glucose in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects with mutations in the diabetes susceptibility gene MODY3 on chromosome 12. Diabetes. 1996;45(11):1503–10. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.11.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehto M, Tuomi T, Mahtani MM, Widen E, Forsblom C, Sarelin L, et al. Characterization of the MODY3 phenotype. Early-onset diabetes caused by an insulin secretion defect. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;99(4):582–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI119199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Servitja JM, Pignatelli M, Maestro MA, Cardalda C, Boj SF, Lozano J, et al. Hnf1alpha (MODY3) controls tissue-specific transcriptional programs and exerts opposed effects on cell growth in pancreatic islets and liver. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29(11):2945–59. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01389-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheret C, Doyen A, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha controls renal expression of the Npt1-Npt4 anionic transporter locus. Journal of molecular biology. 2002;322(5):929–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00816-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontoglio M, Prie D, Cheret C, Doyen A, Leroy C, Froguel P, et al. HNF1alpha controls renal glucose reabsorption in mouse and man. EMBO reports. 2000;1(4):359–65. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pontoglio M, Barra J, Hadchouel M, Doyen A, Kress C, Bach JP, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell. 1996;84(4):575–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benoit YD, Pare F, Francoeur C, Jean D, Tremblay E, Boudreau F, et al. Cooperation between HNF-1alpha, Cdx2, and GATA-4 in initiating an enterocytic differentiation program in a normal human intestinal epithelial progenitor cell line. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2010;298(4):G504–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00265.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boudreau F, Rings EH, van Wering HM, Kim RK, Swain GP, Krasinski SD, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha, GATA-4, and caudal related homeodomain protein Cdx2 interact functionally to modulate intestinal gene transcription. Implication for the developmental regulation of the sucrase-isomaltase gene. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(35):31909–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell GI, Kayano T, Buse JB, Burant CF, Takeda J, Lin D, et al. Molecular biology of mammalian glucose transporters. Diabetes care. 1990;13(3):198–208. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood IS, Trayhurn P. Glucose transporters (GLUT and SGLT): expanded families of sugar transport proteins. The British journal of nutrition. 2003;89(1):3–9. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrizas M, Maestro MA, Boj SF, Paniagua A, Casamitjana R, Gomis R, et al. Hepatic nuclear factor 1-alpha directs nucleosomal hyperacetylation to its tissue-specific transcriptional targets. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21(9):3234–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.3234-3243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saaf AM, Halbleib JM, Chen X, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Nelson WJ, et al. Parallels between global transcriptional programs of polarizing Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells in vitro and gene expression programs in normal colon and colon cancer. Molecular biology of the cell. 2007;18(11):4245–60. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremblay E, Auclair J, Delvin E, Levy E, Menard D, Pshezhetsky AV, et al. Gene expression profiles of normal proliferating and differentiating human intestinal epithelial cells: a comparison with the Caco-2 cell model. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2006;99(4):1175–86. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verzi MP, Shin H, He HH, Sulahian R, Meyer CA, Montgomery RK, et al. Differentiation-specific histone modifications reveal dynamic chromatin interactions and partners for the intestinal transcription factor CDX2. Developmental cell. 2010;19(5):713–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Browne JA, Harris A, Leir SH. An optimized protocol for isolating primary epithelial cell chromatin for ChIP. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e100099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fossum SL, Mutolo MJ, Yang R, Dang H, O'Neal WK, Knowles MR, et al. Ets homologous factor regulates pathways controlling response to injury in airway epithelial cells. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(22):13588–98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular cell. 2010;38(4):576–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerschner JL, Harris A. Transcriptional networks driving enhancer function in the CFTR gene. The Biochemical journal. 2012;446(2):203–12. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ott CJ, Suszko M, Blackledge NP, Wright JE, Crawford GE, Harris A. A complex intronic enhancer regulates expression of the CFTR gene by direct interaction with the promoter. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2009;13(4):680–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mouchel N, Henstra SA, McCarthy VA, Williams SH, Phylactides M, Harris A. HNF1alpha is involved in tissue-specific regulation of CFTR gene expression. The Biochemical journal. 2004;378:909–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031157. Pt 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosalia N, Yang R, Kerschner JL, Harris A. FOXA2 regulates a network of genes involved in critical functions of human intestinal epithelia cells. Physiological genomics. 2015 doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00024.2015. physiolgenomics 00024 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ott CJ, Blackledge NP, Kerschner JL, Leir SH, Crawford GE, Cotton CU, et al. Intronic enhancers coordinate epithelial-specific looping of the active CFTR locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(47):19934–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900946106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gheldof N, Smith EM, Tabuchi TM, Koch CM, Dunham I, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, et al. Cell-type-specific long-range looping interactions identify distant regulatory elements of the CFTR gene. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(13):4325–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillen AE, Harris A. Transcriptional regulation of CFTR gene expression. Frontiers in bioscience. 2012;4:587–92. doi: 10.2741/401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rui L, Fisher TL, Thomas J, White MF. Regulation of insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling by proteasome-mediated degradation of insulin receptor substrate-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(43):40362–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takano A, Usui I, Haruta T, Kawahara J, Uno T, Iwata M, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway regulates insulin signaling via subcellular redistribution of insulin receptor substrate 1 and integrates nutritional signals and metabolic signals of insulin. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21(15):5050–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5050-5062.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobin V, Le Gall M, Fioramonti X, Stolarczyk E, Blazquez AG, Klein C, et al. Insulin internalizes GLUT2 in the enterocytes of healthy but not insulin-resistant mice. Diabetes. 2008;57(3):555–62. doi: 10.2337/db07-0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kellett GL, Brot-Laroche E, Mace OJ, Leturque A. Sugar absorption in the intestine: the role of GLUT2. Annual review of nutrition. 2008;28:35–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Courtois G, Morgan JG, Campbell LA, Fourel G, Crabtree GR. Interaction of a liver-specific nuclear factor with the fibrinogen and alpha 1-antitrypsin promoters. Science. 1987;238(4827):688–92. doi: 10.1126/science.3499668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wederell ED, Bilenky M, Cullum R, Thiessen N, Dagpinar M, Delaney A, et al. Global analysis of in vivo Foxa2-binding sites in mouse adult liver using massively parallel sequencing. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36(14):4549–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lalmansingh AS, Karmakar S, Jin Y, Nagaich AK. Multiple modes of chromatin remodeling by Forkhead box proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1819(7):707–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James R, Kazenwadel J. Homeobox gene expression in the intestinal epithelium of adult mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266(5):3246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D'Angelo A, Bluteau O, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Gresh L, Doyen A, Garbay S, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha and beta control terminal differentiation and cell fate commitment in the gut epithelium. Development. 2010;137(9):1573–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.044420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamagata K, Furuta H, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, Menzel S, Cox NJ, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) Nature. 1996;384(6608):458–60. doi: 10.1038/384458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, Saxena R, Soranzo N, Jackson AU, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nature genetics. 2010;42(2):105–16. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ibberson M, Uldry M, Thorens B. GLUTX1, a novel mammalian glucose transporter expressed in the central nervous system and insulin-sensitive tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(7):4607–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phay JE, Hussain HB, Moley JF. Cloning and expression analysis of a novel member of the facilitative glucose transporter family, SLC2A9 (GLUT9) Genomics. 2000;66(2):217–20. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao FQ, Keating AF. Functional properties and genomics of glucose transporters. Current genomics. 2007;8(2):113–28. doi: 10.2174/138920207780368187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneider TD, Stephens RM. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic acids research. 1990;18(20):6097–100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.