Abstract

Background

School-based influenza immunization campaigns could mitigate the effects of influenza epidemics. A large countywide school-based immunization campaign was launched in Knox County, Tennessee, in 2005. Assessment of campaign effects requires identification of appropriate control populations. We hypothesized that contiguous counties would share similar pre-campaign patterns of influenza activity.

Methods

We compared the burden of influenza emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations between Knox County (Knox) and eight counties surrounding Knox (Knox-surrounding) during five consecutive pre-campaign influenza seasons (2000–01 through 2004–05). Laboratory-defined influenza seasons were used to measure the weekly incidence of medically attended acute respiratory illnesses (MAARI) attributable to influenza in school-aged children 5–17 years old (campaign target) as well as in other age groups. Seasonal rates of MAARI attributable to influenza for Knox and Knox-surrounding counties were compared using rate ratios.

Results

During five consecutive influenza seasons, MAARI attributable to influenza showed synchronous temporal patterns in school-aged children from Knox and Knox-surrounding counties. The average seasonal rates of ED visits attributable to influenza were 12.37 (95% CI: 10.32–14.42) and 13.14 (95% CI: 11.23–15.05) per 1000, respectively. The respective average seasonal influenza hospitalization rates for Knox and Knox-surrounding were 0.38 (95% CI: 0–0.79) and 0.46 (95% CI: 0.07–0.85) per 1000 children. Rate ratio analyses indicated no significant differences in the incidence of MAARI attributable to influenza between school-aged children from Knox and Knox-surrounding counties. Estimates for other age groups showed similar patterns.

Conclusion

Before the Knox school-based influenza immunization campaign, influenza resulted in an average of about 12 ED visits and 0.4 hospitalizations per 1000 school-aged children annually in Knox County. Since similar morbidity was observed in surrounding counties, they could serve as a control population for the assessment of the campaign effects.

INTRODUCTION

Seasonal influenza is a common cause of childhood morbidity in the United States. The incidence of influenza is high in children, with attack rates of symptomatic illness of 15–20% every year.[1, 2] Children are infected early during epidemics and shed viruses for longer periods than adults, facilitating the spread of the virus into the communities.[3–5] Hence, protection of children through immunization has been proposed as a preventive measure to reduce the transmission of influenza, reduce childhood morbidity, and reduce morbidity among older age groups.[4, 6–8] Starting in 2004, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization of young children against influenza. Those recommendations have evolved rapidly and by 2008, routine influenza immunization was recommended for all children aged 6 months or older.[9]

Despite formal recommendations, influenza immunization coverage levels in targeted age groups remained suboptimal. Additional strategies are needed to encourage administration of influenza vaccines to critical populations in a timely and efficient way.[10]

Schools, where children interact in close contact, provide a ready conduit for transmission and subsequent spread of influenza in the community.[4, 11] However, schools also provide opportunities for effective reduction of influenza transmission. The ‘captive’ nature of school populations makes them suitable for large scale interventions.[12] Previous experience showed that successful school-based immunization programs can be implemented and that it is indeed possible to overcome several of the known barriers for influenza immunization,[13, 14] such as scheduling and keeping healthcare visit appointments.[12]

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is an attractive option for school-based interventions. LAIV has consistently shown higher efficacy than inactivated influenza vaccines in young children.[15–19] LAIV also reduced virus shedding in young children, compared with the inactivated influenza vaccines.[20] A major advantage of LAIV is its high acceptability and ease of administration because it is a nasal spray rather than an injection.[12]

Mathematical models have described the advantages of immunizing school-aged children against influenza and suggest substantial population benefits.[21, 22] These studies have increased in number since the beginning of the current 2009 influenza pandemic and provided information to guide the allocation of influenza vaccines. Given the current concerns about the supply of pandemic influenza vaccines, defining the optimal strategy to maximize the population impact of an influenza immunization program with limited vaccine supply is crucial.

In spite of the theoretical basis for large scale immunization of school-aged children, real-life demonstration of population benefits (including herd effects) is limited and confirmation of model predictions is scarce. A recent cluster randomized trial assessed the population benefits of school-based immunization programs in relatively isolated Hutterite colonies.[23] However, assessments of the effectiveness of these interventions in the general population are challenging. The incidence of influenza morbidity is usually reported for large populations, aggregating local or regional influenza activity. However, during typical influenza seasons, the incidence and timing of influenza epidemics varies across populations. Previous observations from active population-based surveillance of influenza have shown important seasonal and regional differences in influenza incidence.[24] Moreover, influenza related-healthcare utilization patterns may also differ by populations. An appropriate control population to evaluate a community intervention would ideally have both similar influenza activity and similar healthcare utilization patterns.

Few studies, however, have documented the activity of influenza in small areas or populations during consecutive seasons. In preparation for the assessment of the effectiveness of a large county-wide immunization campaign in Knox County, Tennessee, we compared the incidence of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations for acute respiratory infections attributable to influenza in two contiguous populations to assess the feasibility of using one as a control group. We hypothesized that contiguous populations would share similar influenza activity and healthcare utilization patterns.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort study to estimate the incidence of medically attended acute respiratory illnesses (MAARI) attributable to influenza in Knox County and in eight counties surrounding Knox (Knox-surrounding counties). Weekly electronic healthcare information was analyzed and coupled with local laboratory-based influenza testing to estimate the incidence of MAARI attributable to influenza.

Source of data: The Tennessee Hospital Discharge Data System

As required by Tennessee Law, all hospitals licensed by the Tennessee Department of Health report patient-level inpatient and outpatient information to the State. This information is collected systematically for administrative purposes and the data include inpatient, emergency department (ED), outpatient 23-hour observation, and ambulatory surgery records. This data source provides virtually complete coverage of hospital-based healthcare encounters, regardless of payment sources, for the State of Tennessee.

Laboratory-confirmed influenza infections

Influenza activity was measured using viral testing results. We analyzed laboratory results of influenza antigen detection rapid tests performed at the East Tennessee Children Hospital (ETCH), the regional hospital that provides care for children from Knox and Knox-surrounding counties. Rapid tests results were used to define timing of influenza activity for five consecutive influenza seasons, from 2000–01 through 2004–05.[25]

Influenza seasons

An influenza season began on the week when the cumulative proportion of positive influenza rapid tests observed during November through April (referred to as Winter) attained 2.5%. The season ended on the week when the cumulative proportion reached 97.5%. Thus, each season contained at least 95% of positive influenza rapid tests.[25] Using this information, we also defined all non-influenza winter time as peri-Influenza season.[1]

Study outcomes

Medically attended acute respiratory illness (MAARI) was defined using International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification Ninth Revision (ICD9-CM) codes, encompassing diagnoses of otitis media and sinusitis, lower and upper respiratory tract disease and fever. (ICD9-CM: 381, 382, 383, 460, 461, 462, 463, 464, 465, 466, 480, 481, 482, 483, 484,485, 486, 487,490, 491, 493 and 7806).[16, 26–28] Data sources could record more than one diagnosis per healthcare encounter and diagnosis codes identified in any diagnosis position were used to define MAARI.

To obtain estimates for specific healthcare settings, all hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department were made mutually exclusive and to reduce the possibility of counting the same episode more than once, subjects could contribute a maximum of one healthcare encounter per setting per week. For instance, if during the same study week a patient was admitted to the hospital after an ED visit, only the hospitalization was included in the analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Weekly MAARI rates were calculated using the number of MAARIs and population estimates obtained from the US Census Bureau.[29] School-age children (5–17 years old) were the primary study population and secondary analyses included the age groups: <5, 18–49, 50–64 and 65 or more years. Additional estimates were also obtained for children aged 5–11 and 12–17 years, and adults aged 18–34 and 35–49 years.

To estimate age-specific excess MAARI morbidity attributable to influenza we first estimated the weekly rates that would be expected in the absence of influenza. This baseline was calculated using separate estimates for each age group and count-event models that included indicators for calendar week, cyclical terms to account for seasonality and one indicator for influenza activity (proportion of positive influenza rapid tests).[30–32] Since Poisson models showed data overdispersion, we used the more robust negative binomial models for all estimations and allowed for non-linearity of the weekly time term using restricted cubic splines. Using coefficients from these models, we estimated the predicted baseline MAARI rates by setting the influenza indicator to zero for all observations, that is, these predicted baseline MAARI rates represent the rates that would be expected in the absence of influenza activity.[33, 34] Then, the difference between observed MAARI weekly rates and the baseline predicted rates during the influenza seasons represented the excess MAARI morbidity attributable to influenza.

A secondary analysis also estimated age-specific excess MAARI morbidity attributable to influenza using the rate difference method.[1, 30, 35] For this approach, the rate difference, which represented the excess MAARI attributable to influenza, was calculated for each season, by subtracting peri-influenza season MAARI rates from influenza season estimates.[30] Rate differences were set to zero for those seasons where the peri-Influenza season estimates exceeded the influenza season estimates.

The seasonal excess MAARI attributable to influenza was estimated separately for Knox and for Knox-surrounding counties. Rates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each season and for each age group, and excess MAARI rates attributable to influenza between Knox and Knox-surrounding counties were compared using rate ratios.[25] Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for the rate ratios were calculated using the Delta method[36] and ratios encompassing one indicated that influenza excess rates from Knox and Knox-surrounding counties were not statistically different.

All analyses were stratified by setting (hospitalizations and ED visits) and age group. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.3 and Stata 10.1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University and by the State of Tennessee Department of Health.

RESULTS

Study populations

Knox is an urban county that includes the city of Knoxville and is located in the East Tennessee region. According to the US Census Bureau, Knox had a population of 385,899 persons in 2000 that was predominantly white (88.7%). Children aged 5–17 years accounted for 16.2% of the Knox population. The proportion of the Knox County population that attained high school graduation or higher education was 82.5% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of Knox and Knox-surrounding counties

| Knox County | Knox-surrounding counties* |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total population (n) | 385,899 | 422,064 |

| Age groups (%) | ||

| <5 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| 5 to 17 | 16.2 | 17.0 |

| 18 to 49 | 49.5 | 44.3 |

| 50 to 64 | 15.6 | 18.4 |

| 65 or more | 12.6 | 14.4 |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Female | 51.7 | 51.4 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 88.7 | 96.1 |

| Black | 8.7 | 2.2 |

| Other | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| Enrolled in school (aged ≥3 years) (%) | ||

| Nursery school, preschool | 6.1 | 5.1 |

| Kindergarten | 4.7 | 5.7 |

| Elementary school (grades 1–8) | 37.8 | 50.5 |

| High school (grades 9–12) | 18.3 | 23.5 |

| College or graduate school | 33.1 | 15.3 |

| Educational attainment (aged ≥25 years) (%) | ||

| High school graduate or higher | 82.5 | 71.2 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 29 | 13.8 |

| Income | ||

| Median household income (US$) | 37,454 | 33,731 |

| Families below poverty level (%) | 8.4 | 10.6 |

Data are from the US Census Bureau for year 2000.

The estimated population of Knox-surrounding counties combined was 422,064 in 2000. Approximately 96.1% of the population was white. Children aged 5–17 years accounted for 17% of the population of Knox-surrounding counties. The proportion of the Knox-surrounding counties population that attained high school graduation or higher education was 71.2% (Table 1).

MAARI ED visits and hospitalizations

During the five consecutive winter seasons, there were 22,206 MAARI ED visits and 966 MAARI hospitalizations among Knox school-age children aged 5–17 years. In Knox-surrounding counties, the numbers of ED visits and hospitalizations were 25,550 and 1137, respectively. The average number of weeks in each laboratory defined-influenza season was 12 (range: 10–14 weeks).

Patterns of influenza activity

Weekly MAARI rates showed similar temporal patterns for Knox and Knox-surrounding counties. Patterns overlapped throughout the observation period, with laboratory-defined influenza seasons consistently containing the highest seasonal MAARI incidence peaks. Throughout the study seasons, MAARI incidence rates followed similar patterns for hospitalizations and ED visits (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Influenza activity among school-age children, ED and hospitalization rates, 2000–2005

Footnote: Laboratory confirmed influenza seasons are highlighted in yellow. Vertical lines indicate the boundaries of influenza and peri-influenza seasons.

Due to the inconsistent timing in the onset of influenza seasons, the distribution of the winter peri-Influenza seasons varied across seasons. Notably, the moderately severe 2003–2004 influenza season started abruptly at the beginning of the winter. Hence, that peri-Influenza season was restricted to winter weeks that followed the end of the epidemic (Figure 1).

Estimation of influenza activity

Seasonal excess rates of ED visits and hospitalization for MAARI attributable to influenza among school-aged children aged 5–17 years were similar in Knox and in Knox-surrounding counties throughout the study seasons.

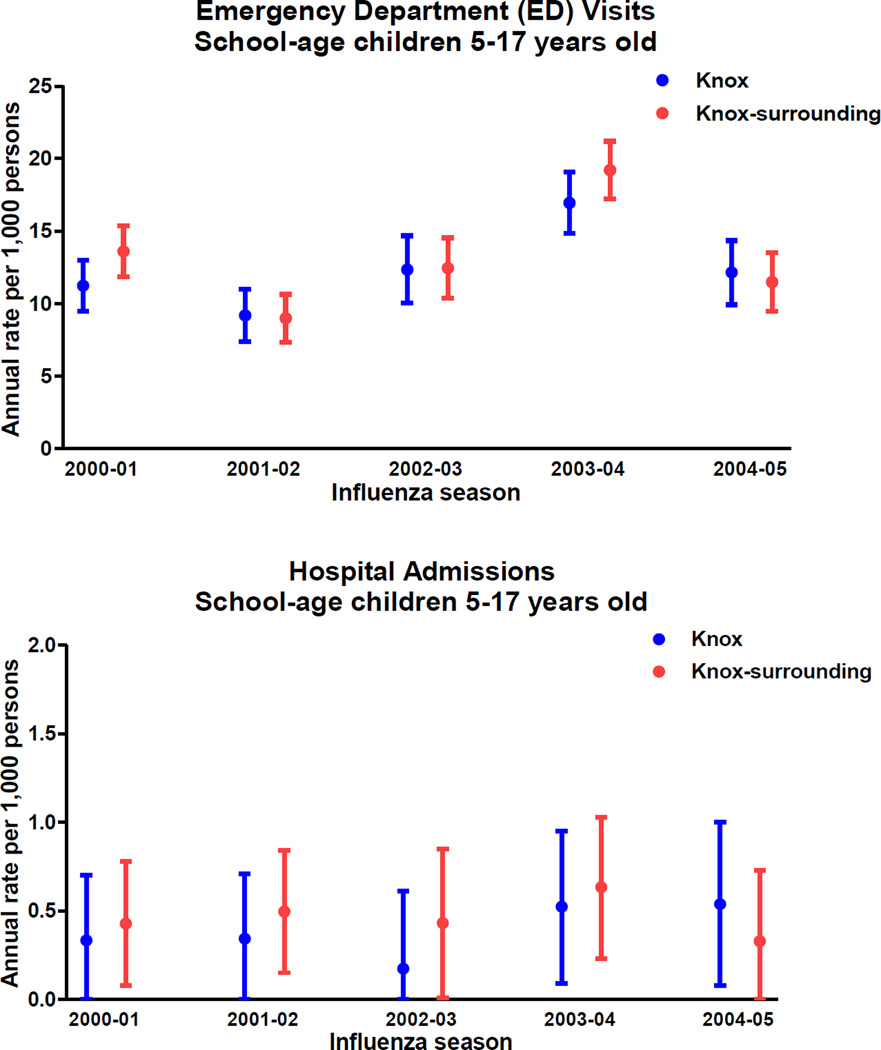

Seasonal rates of ED visits due to MAARI attributable to influenza for Knox County ranged from 9.18 (95% CI: 7.38–10.99) per 1000 children (2001–02 season) to 16.94 (95% CI: 14.83–19.06) per 1000 children (2003–04 season). The respective seasonal rates of ED visits for Knox-surrounding counties ranged from 8.98 (95% CI: 7.32–10.64) to 19.21 (95% CI: 17.22–21.19) per 1000 children (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated seasonal Influenza incidence among school-age children, ED visits and hospitalization rates

Footnote: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Similarly, seasonal hospitalization rates for Knox children ranged from 0.17 (95% CI: 0–0.61) to 0.54 (95% CI: 0.08–1.00) per 1000 children for seasons 2002–03 and 2004–05, respectively. For Knox-surrounding counties, seasonal rates ranged from 0.33 (95% CI: 0–0.73) to 0.63 (95% CI: 0.23–1.03) for seasons 2004–05 and 2003–04, respectively (Figure 2).

Overall average seasonal ED visit rates for MAARI attributable to influenza for Knox and Knox-surrounding Counties were 12.37 (95% CI: 10.32–14.42) and 13.14 (95% CI: 11.23–15.05) per 1000 children aged 5–17 years. The respective average seasonal hospitalization rates for MAARI attributable to influenza was 0.38 (95% CI: 0–0.79) and 0.46 (95% CI: 0.07–0.85) per 1000 children aged 5–17 years.

Comparison of influenza activity

In the rate ratio analyses, pair-wise comparisons of rates of MAARI attributable to influenza from Knox and Knox-surrounding counties were similar throughout the study seasons. Rate ratio estimates indicated that influenza activity in Knox was not significantly different from that in Knox-surrounding counties. Due to the small number of hospitalizations due to MAARI attributable to influenza in this age group, ratios and confidence intervals could not be calculated for all seasons. Rate ratios for all seasons combined indicated no statistically significant differences in influenza activity between the study populations (Table 2). Rate ratios for children aged 5–11 and 12–17 years were consistent with those from the primary age group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ratios of MAARI rates attributable to influenza (Knox / Knox-surrounding counties) among school-age children aged 5–17 years

| Influenza season |

ED visits Rate Ratio |

95% CI | Hospitalizations Rate Ratio |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2001 | 0.83 | (0.66, 1.00) | 0.78 | (*, 1.86) |

| 2001–2002 | 1.02 | (0.74, 1.30) | 0.69 | (*, 1.57) |

| 2002–2003 | 0.99 | (0.74, 1.24) | 0.40 | (*, 1.49) |

| 2003–2004 | 0.88 | (0.74, 1.02) | 0.83 | (*, 1.68) |

| 2004–2005 | 1.06 | (0.79, 1.33) | 1.63 | (*, 4.08) |

| 2000–2005 | 0.94 | (0.73, 1.15) | 0.82 | (*, 1.95) |

95% CI, confidence intervals. Rate ratios represent Knox rates divided by Knox-surrounding counties rates

Ratio was not computed because there was no excess MAARI hospitalizations attributable to influenza in at least one of the populations.

Other age groups

Similar average seasonal rates of MAARI attributable to influenza were consistently observed in other age groups. Among all age groups, children aged less than 5 years consistently bore the highest burden of MAARI attributable to influenza in both ED and hospital settings. The rate ratios indicated that activity of influenza was similar in Knox and Knox-surrounding counties in both settings and all age groups, except in the subgroup aged 18–34 years, in which ED visit rates for Knox were lower than those from Knox-surrounding counties (Table 3 and Supplementary material).

Table 3.

Average seasonal rate of MAARI attributable to influenza by population, age group and setting, 2000–2005

| Emergency Department visits per 1,000 |

Hospitalizations per 1,000 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Knox rates |

Knox- surrounding rates |

Rate Ratio | Knox rates |

Knox- surrounding rates |

Rate Ratio |

| Less than 5 years | 38.22 | 41.45 | 0.92 (0.70, 1.14) | 2.95 | 4.18 | 0.71 (0.10, 1.32) |

| 5 to 17 years | 12.37 | 13.14 | 0.94 (0.73, 1.15) | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.82 (**, 1.95) |

| 5 to 11 years | 15.01 | 15.18 | 0.99 (0.72, 1.26) | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.83(**, 2.12) |

| 12 to 17 years | 9.73 | 11.16 | 0.87 (0.57, 1.17) | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.95 (**, 2.53) |

| 18 to 49 years | 4.25 | 5.03 | 0.84 (0.61, 1.07) | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.83 (**, 1.69) |

| 18 to 34 years | 5.38 | 7.35 | 0.73(0.51, 0.95)* | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.96(**, 2.10) |

| 35 to 49 years | 3.13 | 3.12 | 1.00 (0.50, 1.50) | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.69 (**, 1.69) |

| 50 to 64 years | 2.55 | 2.91 | 0.88 (0.37, 1.39) | 1.20 | 1.63 | 0.74 (**, 1.49) |

| 65 years or older | 3.19 | 3.32 | 0.96 (0.46, 1.46) | 3.65 | 4.42 | 0.83 (0.31, 1.35) |

Rate ratio 95% confidence intervals (CI) did not include 1.

Ratio was not computed because there was no excess MAARI hospitalizations attributable to influenza in at least one of the populations.

Secondary Analyses

Estimates based on the rate difference approach yielded similar results to those provided by the primary analysis. The rate ratios indicated that activity of influenza was similar in Knox and Knox-surrounding counties in both settings and in most age groups. The only exception was the ratio of ED visit rates for adults aged 18–49 years (specifically adults aged 18–34 years), for whom rates were lower in Knox than in Knox-surrounding counties (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average seasonal rate of MAARI attributable to influenza by population, age group and setting, 2000–2005 (Rate difference method)

| Emergency Department visits per 1,000 |

Hospitalizations per 1,000 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Knox rates |

Knox- surrounding rates |

Rate Ratio | Knox rates |

Knox- surrounding rates |

Rate Ratio |

| Less than 5 years | 46.13 | 51.34 | 0.90 (0.72, 1.08) | 4.68 | 6.13 | 0.76 (0.33, 1.19) |

| 5 to 17 years | 14.62 | 14.97 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.17) | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.94 (**, 2.81) |

| 5 to 11 years | 18.03 | 18.22 | 0.99 (0.76, 1.22) | 0.39 | 0.36 | 1.08 (**, 3.65) |

| 12 to 17 years | 10.49 | 11.21 | 0.94 (0.62, 1.26) | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.75 (**, 3.65) |

| 18 to 49 years | 4.79 | 5.96 | 0.80 (0.61, 0.99)* | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.77 (**, 1.74) |

| 18 to 34 years | 5.60 | 8.10 | 0.69 (0.49, 0.89)* | 0.35 | 0.29 | 1.21 (**, 3.42) |

| 35 to 49 years | 3.90 | 3.98 | 0.98 (0.58, 1.38) | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.55 (**, 1.64) |

| 50 to 64 years | 2.85 | 3.20 | 0.89 (0.41, 1.37) | 1.29 | 1.75 | 0.74 (0.01, 1.47) |

| 65 years or older | 3.35 | 3.88 | 0.86 (0.44, 1.28) | 4.15 | 5.12 | 0.81 (0.35, 1.27) |

Rate ratio 95% confidence intervals (CI) did not include 1.

Ratio was not computed because there was no excess MAARI hospitalizations attributable to influenza in at least one of the populations.

DISCUSSION

The study of five consecutive laboratory-characterized influenza seasons indicated that influenza activity had consistently similar temporal patterns in Knox and Knox-surrounding counties. Patterns of influenza activity were synchronous in both populations and estimated rates of MAARI attributable to influenza were similar, indicating that Knox-surrounding counties could serve as controls for the assessment of the Knox school-based influenza immunization campaign.

The target population of the Knox-school based immunization campaign was children aged 5–17 years. Accordingly, our assessment of pre-campaign years focused primarily on this age group. Although influenza activity in the study populations varied widely from season to season, the estimated excess disease attributable to influenza was consistently similar between children aged 5–17 years from Knox and Knox-surrounding counties. Similar rates were also observed among other age groups, suggesting that age groups, other than 5–17 years old, could also be examined, allowing the assessments of both direct and indirect protection derived from the Knox immunization campaign. Nevertheless, ED visit rates for Knox adults aged 18–34 years were consistently lower than those for Knox-surrounding counties. This should be considered during the assessment of the Knox intervention effects.

Although a number of studies estimated the burden of disease attributable to influenza for large single populations, few studies have compared estimates between contiguous populations. Data from the regional children’s hospital in Knoxville indicated that during 2000–2005 Knox and Knox-surrounding counties had almost identical influenza epidemics based on laboratory tests results.[25] Furthermore, our findings indicate that the effects of influenza or other factors affecting influenza related-healthcare utilization were likely similar between Knox and Knox-surrounding counties during the pre-campaign seasons.

Previous studies have calculated rates of MAARI attributable to influenza for school aged children. In New York City, ED seasonal visit rates of MAARI attributable to influenza (seasons 2001–2005) ranged from 4 to 12 and from 1 to 8 per 1000, among children aged 5–12 and 13–17 years old, respectively.[37] Similarly, in a multicenter cluster randomized controlled trial that evaluated the effectiveness of school-based influenza immunizations during the 2004–2005 season, the rate of all-cause ED visits (including influenza) among children aged 5 years or older in control households was 13 per 1000.[38] These estimates appear consistently lower than our seasonal estimated ED visit rates of MAARI attributable to influenza for Knox and Knox-surrounding counties (12.37 and 13.14 per 1000, respectively). These differences are not completely unexpected, however, since previous studies observed higher use of healthcare services in Knox County, compared with other counties in Tennessee.[39, 40] More importantly, these observations highlight the value of selecting control populations with similar background influenza activity and healthcare utilization patterns before the assessment of any intervention effects.

Based on combined seasonal estimates and data for children aged 5–17 years from this study, we estimated the campaign effects that could be detectable using our rate ratios approach. Assuming that Knox rates of MAARI attributable to influenza would decrease with a hypothetical intervention (i.e. a countywide influenza immunization campaign) while keeping all other sources of variability the same, we estimated that our methods will be able to detect a true rate ratio of 0.80 in the ED settings. Given the small number of events and the large variability observed, the detectable rate ratio for hospitalizations would be 0.09. This detectable reduction in ED rates of MAARI attributable to influenza could be translated to a detectable vaccine effectiveness of 40%, assuming a 50% vaccination rate of Knox children aged 5–17 years, and no immunization occurred in Knox-surrounding counties. Nevertheless, we anticipate that estimates of campaign effects on MAARI hospitalization rates would carry considerable uncertainly.

The strengths of our study are the use of large data sources that collect data on all hospitalizations and emergency department visits for the study populations. This information was systematically collected for administrative purposes and thus, unlikely to be affected by recall issues. Moreover, the data collected included all hospital-based care without regard to payment sources and, thus it was virtually free of selection issues. Furthermore, the use of laboratory-confirmed influenza information, to define the influenza seasons, reduced the potential misclassification of periods with influenza activity. Of note, our laboratory-defined seasons consistently included the peaks in MAARI incidence lending support to our definition of influenza seasons and to the fact that influenza is a major contributor of MAARI. Finally, we used two different approaches to estimate excess MAARI attributable to influenza and both approaches yielded similar estimates and identical conclusions.[30, 37, 41]

Despite those strengths, the interpretation of our findings requires the consideration of some caveats. First, we used administrative data that lacked virological confirmation for all observed MAARI. Although our methods aimed to detect excess disease attributable to influenza in each population, excess MAARI estimates may be influenced by other factors. Our methods assumed that non-influenza respiratory illness is similar in influenza and peri-influenza periods. Nevertheless, our laboratory-confirmed influenza seasons consistently captured the peaks of MAARI, and we considered that potential misclassification of influenza-related MAARI would likely be similar in the two study populations. Second, during the study years, some seasons had mild influenza activity, resulting in small number of MAARI hospitalizations and relatively unstable estimates, complicating the rate ratio comparison of the populations. Moreover, during some seasons, there was no detectable excess in MAARI hospitalizations attributable to influenza. Although our estimated rate ratios indicated that influenza activity was similar in both populations across the study seasons, the assessments of changes (i.e. campaign effects) on this rare outcome will be challenging. Third, childhood influenza vaccination could have affected the observed rates. However, we considered this unlikely, since formal recommendations for influenza vaccination of children started in 2004 and the estimated uptake of the vaccine for eligible children in Tennessee was only 4% and 8% for 2003 and 2004, respectively.[42] Finally, information on other potential causes of MAARI during winter months (i.e. respiratory syncytial virus [RSV], rhinovirus, etc.) was not available for our study. However, our influenza seasons were based on detailed laboratory-confirmed influenza data and previously studies suggest that estimates including or excluding RSV data did not significantly affect influenza estimates [1, 2, 32]. More importantly, RSV activity would be of greater concern in younger age groups than among children aged 5–17 years old, the main age group in our study.

In preparation for the evaluation of a large countywide school-based influenza immunization campaign, our study demonstrated that during five consecutive pre-campaign seasons, Knox and Knox-surrounding counties had similar influenza activity. Knox-surrounding counties could serve as controls for the assessments of the impact of the Knox influenza immunization campaign.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Grijalva is supported by a Career Development Award (K01 IP000163) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This study was supported in part by MedImmune, the manufacturer of the live attenuated influenza vaccine. MedImmune had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this report.

We are indebted to the Tennessee Department of Health, Office of Health Statistics which provided hospital discharge data, and to Caroline Graber RN, Jacque Van Audenhove MS and Lori Patterson MD for the collection of influenza antigen detection rapid tests information from East Tennessee Children Hospital.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Drs. Grijalva and Griffin received grant support from MedImmune and speaker honoraria and research support from Wyeth.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neuzil KM, Mellen BG, Wright PF, Mitchel EF, Jr, Griffin MR. The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(4):225–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Izurieta HS, Thompson WW, Piotr K, Shay DK, Davis RL, DeStefano F, et al. Influenza and the rates of hospitalization for respiratory disease among infants and young children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(232):232–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glezen WP. The changing epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza: impetus for new control measures. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004 Nov;23(11 Suppl):S202–S206. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000144662.86396.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glezen WP. Herd protection against influenza. J Clin Virol. 2006 Dec;37(4):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank AL, Taber LH, Wells CR, Wells JM, Glezen WP, Paredes A. Patterns of shedding of myxoviruses and paramyxoviruses in children. JInfectDis. 1981;144(5):433–441. doi: 10.1093/infdis/144.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glezen WP. Anatomy of an urban influenza epidemic. Options for the control of influenza II. J Infect Dis. 1993:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Halloran ME, Longini IM, Jr, Nizam A, Ciuryla V, et al. Population-wide benefits of routine vaccination of children against influenza. Vaccine. 2005 Jan 26;23(10):1284–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halloran ME, Longini IM., Jr Public health. Community studies for vaccinating schoolchildren against influenza. Science. 2006 Feb 3;311(5761):615–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1122143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009 Jul 31;58(RR-8):1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz B, Hinman A, Abramson J, Strikas RA, Allred N, Uyeki T, et al. Universal influenza vaccination in the United States: are we ready? Report of a meeting. J Infect Dis. 2006 Nov 1;194(Suppl 2):S147–S154. doi: 10.1086/507556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glezen WP. Emerging infections: pandemic influenza. Epidemiology Reviews. 1996;18:64–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King JC, Jr, Cummings GE, Stoddard J, Readmond BX, Magder LS, Stong M, et al. A pilot study of the effectiveness of a school-based influenza vaccination program. Pediatrics. 2005 Dec;116(6):e868–e873. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daley MF, Crane LA, Chandramouli V, Beaty BL, Barrow J, Allred N, et al. Influenza among healthy young children: changes in parental attitudes and predictors of immunization during the 2003 to 2004 influenza season. Pediatrics. 2006 Feb;117(2):e268–e277. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoli JM, Szilagyi PG, Rodewald LE. Barriers to immunization and missed opportunities. Pediatr Ann. 1998 Jun;27(6):366–374. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19980601-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belshe RB, Gruber WC, Mendelman PM, Cho I, Reisinger K, Block SL, et al. Efficacy of vaccination with live attenuated, cold-adapted, trivalent, intranasal influenza virus vaccine against a variant (A/Sydney) not contained in the vaccine. Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;136(2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)70097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piedra PA, Gaglani MJ, Kozinetz CA, Herschler G, Riggs M, Griffith M, et al. Herd immunity in adults against influenza-related illnesses with use of the trivalent-live attenuated influenza vaccine (CAIV-T) in children. Vaccine. 2005 Feb 18;23(13):1540–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belshe RB, Edwards KM, Vesikari T, Black SV, Walker RE, Hultquist M, et al. Live attenuated versus inactivated influenza vaccine in infants and young children. N Engl J Med. 2007 Feb 15;356(7):685–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halloran ME, Longini IM, Jr, Gaglani MJ, Piedra PA, Chu H, Herschler GB, et al. Estimating efficacy of trivalent, cold-adapted, influenza virus vaccine (CAIV-T) against influenza A (H1N1) and B using surveillance cultures. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Aug 15;158(4):305–311. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhorer J, Ambrose CS, Dickinson S, Hamilton H, Oleka NA, Malinoski FJ, et al. Efficacy of live attenuated influenza vaccine in children: A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials. Vaccine. 2009 Feb 11;27(7):1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson PR, Feldman S, Thompson JM, Mahoney JD, Wright PF. Immunity to influenza A virus infection in young children: a comparison of natural infection, live cold-adapted vaccine, and inactivated vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1986;154(1):121–127. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basta NE, Chao DL, Halloran ME, Matrajt L, Longini IM., Jr Strategies for Pandemic and Seasonal Influenza Vaccination of Schoolchildren in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Aug 13; doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medlock J, Galvani AP. Optimizing Influenza Vaccine Distribution. Science. 2009 Aug 20; doi: 10.1126/science.1175570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loeb M, Russell ML, Moss L, Fonseca K, Fox J, Earn DJ, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination of children on infection rates in Hutterite communities: a randomized trial. JAMA. Mar 10;303(10):943–950. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, Szilagyi P, Staat MA, Iwane MK, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jul 6;355(1):31–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Griffin MR. Evidence of effectiveness from a large county-wide school-based influenza immunization campaign. Vaccine. 2009 May 5;27(20):2633–2636. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piedra PA, Gaglani MJ, Kozinetz CA, Herschler GB, Fewlass C, Harvey D, et al. Trivalent live attenuated intranasal influenza vaccine administered during the 2003–2004 influenza type A (H3N2) outbreak provided immediate, direct, and indirect protection in children. Pediatrics. 2007 Sep;120(3):e553–e564. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piedra PA, Gaglani MJ, Riggs M, Herschler G, Fewlass C, Watts M, et al. Live attenuated influenza vaccine, trivalent, is safe in healthy children 18 months to 4 years, 5 to 9 years, and 10 to 18 years of age in a community-based, nonrandomized, open-label trial. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e397–e407. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaglani MJ, Piedra PA, Herschler GB, Griffith ME, Kozinetz CA, Riggs MW, et al. Direct and total effectiveness of the intranasal, live-attenuated, trivalent cold-adapted influenza virus vaccine against the 2000–2001 influenza A(H1N1) and B epidemic in healthy children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Jan;158(1):65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Census Bureau. Population Estimates Datasets [internet site] [Accessed January 5th 2009]; Available from http://www.census.gov/popest/datasets.html.

- 30.Thompson WW, Weintraub E, Dhankhar P, Cheng PY, Brammer L, Meltzer MI, et al. Estimates of US influenza-associated deaths made using four different methods. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2009 Jan;3(1):37–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson WW, Comanor L, Shay DK. Epidemiology of seasonal influenza: use of surveillance data and statistical models to estimate the burden of disease. J Infect Dis. 2006 Nov 1;194(Suppl 2):S82–S91. doi: 10.1086/507558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292(11):1333–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schanzer DL, Tam TW, Langley JM, Winchester BT. Influenza-attributable deaths, Canada 1990–1999. Epidemiol Infect. 2007 Oct;135(7):1109–1116. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807007923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Hospitalization attributable to influenza and other viral respiratory illnesses in Canadian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Sep;25(9):795–800. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000232632.86800.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neuzil KM, Wright PF, Mitchel EF, Jr, Griffin MR. The burden of influenza illness in children with asthma and other chronic medical conditions. Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;137:856–864. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.110445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkwood BR, Sterne JAC. Essential Medical Statistics. 2nd. Massachusetts: Blackwell Science; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson DR, Heffernan RT, Paladini M, Konty K, Weiss D, Mostashari F. Monitoring the impact of influenza by age: emergency department fever and respiratory complaint surveillance in New York City. PLoS Med. 2007 Aug;4(8):e247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King JC, Jr, Stoddard JJ, Gaglani MJ, Moore KA, Magder L, McClure E, et al. Effectiveness of school-based influenza vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2523–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perz JF, Craig AS, Coffey CS, Jorgensen DM, Mitchel E, Hall S, et al. Changes in antibiotic prescribing for children after a community-wide campaign. JAMA. 2002 Jun 19;287(23):3103–3109. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poehling KA, Talbot HK, Williams JV, Zhu Y, Lott J, Patterson L, et al. Impact of a school-based influenza immunization program on disease burden: comparison of two Tennessee counties. Vaccine. 2009 May 5;27(20):2695–2700. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansen AG, Sanders EA, Wallinga J, Groen EJ, van Loon AM, Hoes AW, et al. Rate-difference method proved satisfactory in estimating the influenza burden in primary care visits. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008 Aug;61(8):803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Immunization program. Coverage with individual vaccines and vaccination series. [internet site] [Accessed June 15th. 2010]; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/imz-coverage.htm#nis.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.