Abstract

Neonatal meningitis is a rare but devastating condition. Multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria represent a substantial global health risk. We report on an aggressive case of lethal neonatal meningitis due to a MDR Escherichia coli (serotype O75:H5:K1). Serotyping, MDR pattern, and phylogenetic typing revealed that this strain is an emergent and highly virulent neonatal meningitis E. coli isolate. The isolate was resistant to both ampicillin and gentamicin; antibiotics currently used for empiric neonatal sepsis treatment. The strain was also positive for multiple virulence genes including K1 capsule, fimbrial adhesion fimH, siderophore receptors iroN, fyuA and iutA, secreted autotransporter toxin sat, membrane associated proteases ompA and ompT, type II polysaccharide synthesis genes (kpsMTII), and pathogenicity-associated island (PAI)-associated malX gene. The presence of highly-virulent MDR organisms isolated in neonates underscores the need to implement rapid drug resistance diagnostic methods, and should prompt consideration of alternate empiric therapy in neonates with Gram negative meningitis.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, multi-drug resistance, hypervirulence, neonate

Neonatal meningitis continues to be an important cause of neonatal mortality. Survivors those experience lifelong neurologic sequelae including learning and memory impairments[1]. Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Group B Streptococci (GBS) are the leading bacterial meningitis etiologic agents in industrialized and developing countries and E. coli is the leading cause of mortality[2, 3]. Although the incidence, risk factors, predominant serotypes and phylotypes are known, limited information is available on the pathogenesis of meningitis and the unique bacterial factors required. The K1 capsule is known to be a critical determinant in the pathogenesis of meningitis and is believed to support the survival of E. coli inside the central nervous system. The K1 capsule may also facilitate binding to specific receptors in meningeal and brain tissues that allow E. coli to move from the blood to meningeal tissues[4, 5]. Other virulence factors specifically implicated in the pathogenesis of E. coli meningitis are yet to be described. The objective of this study was to describe the clinical aspects of a fatal case of E. coli neonatal meningitis and to evaluate the neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC) isolate at the molecular level. Specifically, the strain was screened for the presence of virulence genes previously reported among extra-intestinal E. coli strains associated with sepsis and neonatal meningitis. We also evaluated the strain by transmission electron microscopy for surface organelles that my play a role in pathogenesis. Lastly, we performed serotyping and multilocus-sequencing typing (MLST) to determine the relationship it may have with previously described NMEC strains.

The Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University approved this study. We retrospectively reviewed medical record of the patient diagnosed and managed for E. coli meningitis at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt (MCJCHV). Medical record information included results from laboratory testing, pathology reports, imaging documentation, in addition to medical and nursing reports. The NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain was isolated from cerebrospinal fluid culture from an infant with neonatal meningitis (described below in clinical case). E. coli K12 DH5α and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC KP700603 strains were used as controls. The strains were cultured aerobically on Luria broth (LB) or MacConkey agar (Becton, Dickinson & Co.) plates at 37°C. For hemolysis and capsule detection, bacteria were grown on sheep blood agar plates (Becton, Dickinson & Co.). Genomic DNA was extracted from E. coli using Gene Elute Bacterial DNA kit (Sigma Inc.) following manufacturer’s instructions. Primer oligonucleotides for PCR DNA amplification were ordered from the Genomic DNA core facility at Vanderbilt University. Supplemental Table 1 lists the primers and the respective targets, including virulence and tDNA genes. PCR assays were conducted as described previously[6, 7]. Briefly, 25ng NMEC genomic DNA was added to 50μl PCR reaction containing primers and GoTaq G2 Hot Start Green Master Mix (Promega Inc.). This mixture was subjected to initial denaturation temperature of 94°C for 5 minutes followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds. Annealing and extension temperatures vary according to primers used (Supplemental Table 2). To assess for the integrity of 12 unique tRNA genes, these genes were amplified using the PCR assay previously described[8]. PCR products were loaded and separated onto 2% TAE agarose for further analysis.

Serotyping was performed at the E. coli reference center at Pennsylvania State University. O antigen was identified using antisera-based methods and PCR-RFLF of fliC gene was employed for H antigen classification.

MLST typing was conducted following the protocols described at http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/. To evaluate the evolutionary relationship between the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain and control strains, single 3423 bp long DNA sequence concatamers from the seven housekeeping gene sequences were generated. MLST concatamer sequences from NMEC-MCJCHV1 and prototype NMEC strains were aligned using ClustalX software available online (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/index.cgi). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the PhyML program by bootstrapping procedure (100 straps) as described previously[9]. Phylogenetic grouping was done following the modified Clermont’s methods, based on PCR identification of chuA, yjaA, TspE4.C2 and arpA genes[10]. Quantitative biofilm assays were performed as previously described[11].

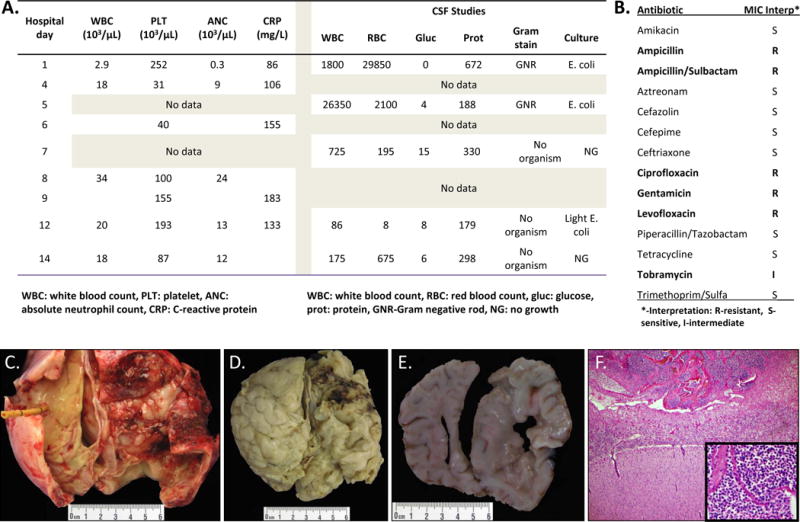

A previously healthy term female infant presented to an emergency department at 30 days of age with poor feeding, fever, and lethargy. Following resuscitation and sepsis evaluation, empiric treatment was started with ampicillin and gentamicin. Laboratory studies revealed a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis and Gram negative bacilli identified by Gram stain, elevated C-reactive protein, and peripheral neutropenia (Figure 1A). Shortly after admission, she developed focal and generalized seizures. On hospital day (HD) 2, blood and CSF cultures grew a Gram negative bacillus, and a 3rd generation cephalosporin was added. The pathogen was identified on HD3 as a multi-drug resistant (MDR) E. coli (Figure 1B). Cephalosporin was continued, and gentamicin was changed to amikacin. The infant exhibited mild hyponatremia but was otherwise in room air and hemodynamically stable when transferred to our institution (HD4). Cranial ultrasound (CUS) on HD4 revealed mild bilateral ventricular dilation with intraventricular echogenic debris] and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed extensive meningitis with a right basal ganglia abscess (HD6, Figures 1C–F, Supplemental Video 1). Clinical seizures recurred on HD9; with respiratory deterioration. MRI on HD13 when she developed dysjunction of multiple cranial sutures and increased occipitofrontal circumference revealed leptomeningeal enhancement and uncal herniation (Supplemental Video 2). Urgent craniotomy was performed, an external ventricular drain was placed, a subdural empyema (positive for E. coli) was drained, and several inaccessible, loculated areas were identified. Inflamed, infected fibrous tissue adherent to the brain could not be fully debrided. She remained intubated and minimally responsive until the day of her death. MRI on HD15 revealed progressive edema and worsening midline shift. Following a family conference on HD16, support was withdrawn, and the infant died.

Figure 1. Virulence of NMEC strain evidenced by clinical laboratory results, gross pathology, and histopathology.

(A) Laboratory characteristics of the patient; (B) Antibiotic sensitivity report for NMEC-MCJCHV1; (C) Gross image of the dorsal brain surface at the vertex of the neocortical hemispheres including attached portions of dura at the lateral edges of the image. The frontal drainage catheter is on the left side and there is extensive fibrinopurulent exudates involving the dura and skull; (D) Gross image of the dorsal brain surface at the vertex of the neocortical hemispheres with the dura removed. There is right frontal and parietal leptomeningitis with diffuse parenchymal involvement (right side of image) and leptomeningitis with cloudy exudate (left side of image); (E) Coronal section of the neocortex at the level of the posterior parietal lobe showing bilateral brain edema and right parietal thickening of the leptomeninges with purulent exudates and friable underlying parenchyma, consistent with encephalitis (right side of image). There is asymmetry of the lobes with compression of the left side, consistent with right to left midline shift; (F) Microscopic image of the right parietal neocortex (H&E, 100×) showing hypercellular leptomeninges (top of image) with abundant acute inflammation (inset, H&E, 400×) including neutrophils and macrophages.

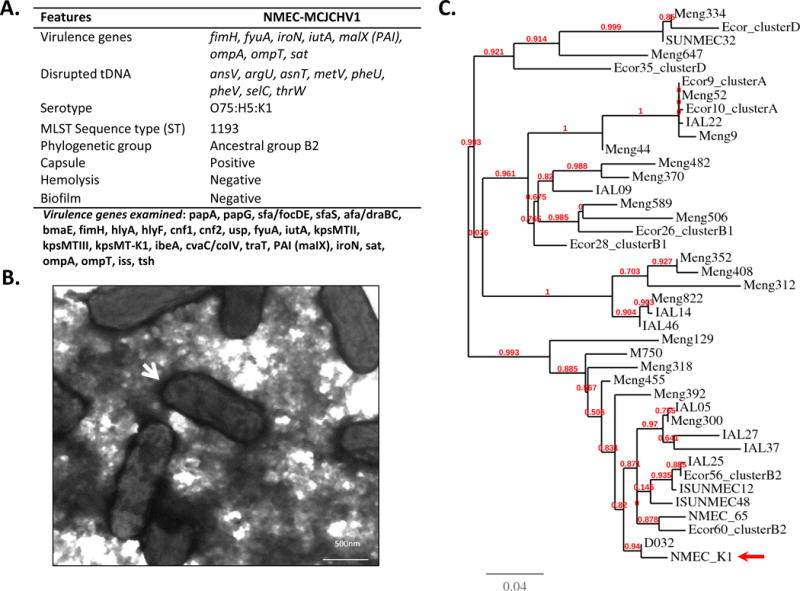

NMEC-MCJCHV1 was evaluated for 27 virulence gene markers using 14 multiplex/uniplex PCR assays (Supplemental Tables 1 & 2). NMEC-MCJCHV1 was positive for genes previously reported among NMEC strains including type I fimbrial adhesin (fimH), siderophore receptors (iroN, fyuA and iutA), secreted autotransporter toxin (sat), and membrane associated proteases (ompA and ompT). NMEC-MCJCHV1 was also positive for type II polysaccharide synthesis genes (kpsMTII); specifically those necessary for K1 capsule synthesis. Furthermore, NMEC-MCJCHV1 was positive for pathogenicity-associated island (PAI)-associated malX gene (Figure 2A). Transmission electron microscopy of the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain revealed an electron dense loosely knitted material surrounding the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain consistent with capsule (Figure 2B). Transfer RNA (tRNA) genes encode tRNA essential for transferring aminoacids to a growing polypeptide chain during protein synthesis. tRNA gene loci, however, are hotspots for DNA recombination events and these sites may be occupied by foreign DNA through horizontal transfer. We evaluated for disruption 12 transfer RNA genes (tDNAs) by PCR assays on the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain and control strains. We showed that the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain had 8 out of 12 tDNA sites disrupted. In contrast, the E. coli K12 DH5α strain had no tDNA sites disrupted. The positive control E. coli ECOR53 strain, member of the ancestral B2 group, had 10 out of 12 tDNA genes disrupted (data not shown).

Figure 2. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of NMEC-MCJCHV1.

(A) Summary of virulence genes, disrupted tRNA genes (tDNA), serotype and other phenotypic features of NMEC-MCJCHV1; (B) Transmission electron micrograph of negatively stained NMEC-MCJCHV1. Note bacterial cells are surrounded by capsular structure (white arrow); (C) Phylogenetic tree of NMEC-MCJCHV1 (arrow), ECOR control strain and different NMEC representing all the known sequence types (STs) from MLST data base.

E. coli isolated from cases of neonatal meningitis express K1 capsule and belong to a discrete number of O serotypes, being O18, O6, O2, O7, O1, O4, the most common[12]. The NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain serotype was O75:H5:K1 (Figure 2A). Phylogenetic typing results showed that the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain belongs to the E. coli ancestral group B2 (Table 1). The MLST typing indicates that this strain is a sequence type (ST) 1193 (Table 1). ST-1193 is represented by only two strains in the E. coli MLST database (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/); one of them was isolated from a subject with urinary tract infection. No virulence information was available on the second strain. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain, and a selected group of E. coli reference collection (ECOR) control strains belonging to phylogenetic groups A, B1, B2 and D. In addition, we included NMEC strains belonging to different STs, retrieved from the E. coli MLST database. Results showed that the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain branched with strains that belong to the phylogenetic B2 type of strains including ECOR 56 and 60 (Figure 2C). Phylogenetic grouping PCR-based assay and phylogenetic grouping DNA-sequence-based data confirms that this strain is a B2 clonal group member.

Table 1.

Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of NMEC-MCJCHV1 clinical isolate.

| Genotype or phenotype | Detection |

|---|---|

| Virulence genes | fimH, fyuA, iroN, iutA, malX (PAI), ompA, ompT, sat |

| Disrupted tDNA | ansV, argU, asnT, metV, pheU, pheV, selC, thrW |

| Serotype | O75:H5:K1 |

| MLST Sequence type (ST) | 1193 |

| Phylogenetic group | Ancestral group B2 |

| Capsule | K1 Positive |

| Hemolysis | Negative |

| Biofilm | Negative |

Severe infections represent the main cause of neonatal mortality accounting for more than one million neonatal deaths worldwide every year. While there is a growing choice of agents against MDR Gram-positive bacteria, the development of new options for MDR Gram-negative bacteria in clinical practice have decreased significantly in the last 20 years[13]. The NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain serotype O75:H18 and K1 capsule, was also positive for 8 virulence gene markers associated with extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), and previously reported among E. coli isolates from neonatal meningitis cases[7, 14, 15]. Of note, 20 other ExPEC-associated virulence genes we searched for were absent in this strain. To further explore other virulence-associated genes, disruption of tDNA genes by episomal DNA insertions including pathogenicity islands, bacteriophages, and insertion elements was evaluated. It is known that episomal DNA not only diversifies the E. coli genome but in some cases dramatically increases virulence[16, 17]. Disrupted tDNA sites may contain virulence genes and pathogenicity islands (PAIs) insertions among intestinal and extraintestinal E. coli pathogens[18]. We demonstrated that 8 out of 12 tDNA sites were disrupted in the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain and we speculate that these tDNA sites are occupied by episomal DNA insertions. Future genomic analysis studies may provide information about novel virulence genes in the NMEC-MCJCHV1 isolate within tRNA insertion sites or outside these sites. These studies may also provide clues about the hypervirulence of this strain.

It is concerning that ampicillin/gentamicin empiric therapy for neonatal sepsis may be ineffective for a growing number of MDR E. coli. Whereas the Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases recommends a third generation cephalosporin in cases of Gram negative meningitis[19], there is an increasing number of reports describing MDR E. coli isolates and the extensive spread of these isolates throughout neonatal intensive care units (NICUs)[20] and the world[21]. Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), often associated with resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones, have recently emerged in community-associated E. coli, and the worldwide clonal dissemination of E. coli sequence type (ST)131 is playing a prominent role[22]. ESBL-producing Gram negative organisms, including K. pneumoniae and E. coli, can cause significant morbidity and mortality in neonates[23]. Although gut microbiome is a reservoir of resistance genes (resistome)[24], it is still unclear the extent of antimicrobial resistance among healthy infants and children. Deep characterization of the pediatric gut-associated resistome, conducted by metagenomics using fecal DNA from 22 healthy US infants and children, identified resistance to 14 antibiotics and recovered genes encoding chloramphenicol acetyltransferases, drug-resistant dihydrofolate reductases, rRNA methyltransferases, multidrug efflux pumps, aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, and tetracycline resistance proteins and every major class of β-lactamases[25]. Prompt control with eradication of the infecting strains from NICUs and multidisciplinary interventions based on standard infection prevention practices are critical for prevention of severe outbreaks[26].

β-Lactams are the predominant class of antimicrobials used in children[27]. Among Gram negative bacteria, the most common mechanism of β-lactam resistance is β-lactamase production[28]. The number of unique, naturally occurring β-lactamases exceeds 1300, making them one of the most numerous enzyme families that has been studied to date[29]. Molecular classes A, B, C, and D define β-lactamases according to amino acid sequence and conserved motifs. Functional groups 1, 2, and 3 are used to assign a clinically useful description to a family of enzymes, with subgroups designated according to substrate and inhibitor profiles[30]. Genotypic-based methods hold promise for the rapid and accurate detection or confirmation of antimicrobial resistance. Unfortunately, these methods only detect resistance, not susceptibility, consequently, phenotypic methods in clinical practice will continue to guide antibiotic therapy, even though turnaround times remain long[31, 32].

While the capsular antigen K1 is well known to be associated with meningitis, the O75 serotype of the NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain is rarely reported from patients with extraintestinal infections. Until now, very few reports have identified E. coli strains with O75 serotype as a case of bacteremia or meningitis[33–35]. The K1 capsule is often associated with meningitis E. coli strains belonging to serotypes O1, O6, O7, O16, O18, O45 and O83[36, 37]. The MLST phylogenetic analysis of this strain also indicates that this is an extraintestinal E. coli, as group B2 and D strains are typically associated with E. coli strains causing sepsis, meningitis, urinary tract infection among other extraintestinal infections. The association of O75:H5 serotype with NMEC strains is atypical and it is rarely observed in meningitis[35]. Importantly, the ST1193 type determined by MLTS analysis of this strain has not been associated previously with meningitis or with MDR, yet it is concerning that emergent pathogens such as this one spread in the community. The NMEC-MCJCHV1 strain has both typical features (K1 capsule, multiple virulence factors) and atypical features (O75:H5 serotype, ST1193, MDR pattern) of NMEC strains. Considering the atypical features, the number of interrupted tDNA identified sites, and the MDR pattern, we propose that NMEC-MCJCHV1 be considered an emergent NMEC pathogen.

We report an emergent lethal neonatal meningoencephalitis E. coli isolate with a MDR pattern, and an unusual serotype and phylogenetic type. The isolate was resistant to ampicillin and gentamicin, the antibiotic combination currently in use for empiric neonatal sepsis treatment. We believe that this E. coli clinical isolate represents a tip of the iceberg with regards to neonatal sepsis caused by MDR and/or hypervirulent Gram negative organisms.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video 1: HD6 Coronal brain MRI showing basal ganglia abscess.

Supplemental Video 2: HD13 Coronal brain MRI showing extensive leptomeningeal enhancement and uncal herniation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful with Dr. Janice Williams at the Electron Microscopy Core Laboratory, Vanderbilt University for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest:

This work was funded in part by the Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine to O.G.G-D; NIH K08GM106143, Thrasher Research Fund to JLW; CTSA award UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences to KRD, and T32 HD068256 – “Preventing prematurity and poor pregnancy outcomes” to KRD. The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the Thrasher Fund, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Barichello T, Dagostim VS, Generoso JS, Simoes LR, Dominguini D, Silvestre C, et al. Neonatal Escherichia coli K1 meningitis causes learning and memory impairments in adulthood. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;272:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logue CM, Doetkott C, Mangiamele P, Wannemuehler YM, Johnson TJ, Tivendale KA, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic traits that distinguish neonatal meningitis-associated Escherichia coli from fecal E. coli isolates of healthy human hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5824–30. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07869-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simonsen KA, Anderson-Berry AL, Delair SF, Davies HD. Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:21–47. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00031-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman JA, Wass C, Stins MF, Kim KS. The capsule supports survival but not traversal of Escherichia coli K1 across the blood-brain barrier. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3566–70. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3566-3570.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim KS, Itabashi H, Gemski P, Sadoff J, Warren RL, Cross AS. The K1 capsule is the critical determinant in the development of Escherichia coli meningitis in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:897–905. doi: 10.1172/JCI115965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman TA, Wu XY, Barchia I, Bettelheim KA, Driesen S, Trott D, et al. Comparison of virulence gene profiles of Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy and diarrheic swine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4782–95. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02885-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:261–72. doi: 10.1086/315217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Canto F, Valenzuela P, Cantero L, Bronstein J, Blanco JE, Blanco J, et al. Distribution of classical and nonclassical virulence genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolates from Chilean children and tRNA gene screening for putative insertion sites for genomic islands. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3198–203. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02473-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dereeper A, Audic S, Claverie JM, Blanc G. BLAST-EXPLORER helps you building datasets for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clermont O, Christenson JK, Denamur E, Gordon DM. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:58–65. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakimoto N, Nishi J, Sheikh J, Nataro JP, Sarantuya J, Iwashita M, et al. Quantitative biofilm assay using a microtiter plate to screen for enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:687–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korhonen TK, Valtonen MV, Parkkinen J, Vaisanen-Rhen V, Finne J, Orskov F, et al. Serotypes, hemolysin production, and receptor recognition of Escherichia coli strains associated with neonatal sepsis and meningitis. Infect Immun. 1985;48:486–91. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.486-491.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzialla C, Borghesi A, Pozzi M, Stronati M. Neonatal infections due to multi-resistant strains: Epidemiology, current treatment, emerging therapeutic approaches and prevention. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;451:71–72015. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JR, Oswald E, O’Bryan TT, Kuskowski MA, Spanjaard L. Phylogenetic distribution of virulence-associated genes among Escherichia coli isolates associated with neonatal bacterial meningitis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:774–84. doi: 10.1086/339343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao Y, Xie Y, Kim KS. Genomic comparison of Escherichia coli K1 strains isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2196–206. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2196-2206.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bielaszewska M, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Kock R, Fruth A, Bauwens A, et al. Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:671–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasko DA, Webster DR, Sahl JW, Bashir A, Boisen N, Scheutz F, et al. Origins of the E. coli strain causing an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:709–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobrindt U, Blum-Oehler G, Nagy G, Schneider G, Johann A, Gottschalk G, et al. Genetic structure and distribution of four pathogenicity islands (PAI I(536) to PAI IV(536)) of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6365–72. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6365-6372.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimberlin M, FAAP David W, Brady, MD, FAAP Michael T, Jackson, MD, FAAP Mary Anne, Long, MD, FAAP Sarah S. Red Book. 30th. Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shakir SM, Goldbeck JM, Robison D, Eckerd AM, Chavez-Bueno S. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of invasive neonatal Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:975–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1370341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathers AJ, Peirano G, Pitout JD. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:565–91. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00116-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giuffre M, Cipolla D, Bonura C, Geraci DM, Aleo A, Di Noto S, et al. Outbreak of colonizations by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 131 in a neonatal intensive care unit, Italy. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2013;2:8. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mavroidi A, Liakopoulos A, Gounaris A, Goudesidou M, Gaitana K, Miriagou V, et al. Successful control of a neonatal outbreak caused mainly by ST20 multidrug-resistant SHV-5-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, Greece. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommer MO, Dantas G, Church GM. Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora. Science. 2009;325:1128–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1176950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore AM, Patel S, Forsberg KJ, Wang B, Bentley G, Razia Y, et al. Pediatric fecal microbiota harbor diverse and novel antibiotic resistance genes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantey JB, Sreeramoju P, Jaleel M, Trevino S, Gander R, Hynan LS, et al. Prompt control of an outbreak caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2013;163:672–9. e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pakyz AL, Gurgle HE, Ibrahim OM, Oinonen MJ, Polk RE. Trends in antibacterial use in hospitalized pediatric patients in United States academic health centers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:600–3. doi: 10.1086/597545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curello J, MacDougall C. Beyond Susceptible and Resistant, Part II: Treatment of Infections Due to Gram-Negative Organisms Producing Extended-Spectrum beta-Lactamases. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:156–64. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-19.3.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bush K. Proliferation and significance of clinically relevant beta-lactamases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1277:84–90. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bush K. The ABCD′s of beta-lactamase nomenclature. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:549–59. doi: 10.1007/s10156-013-0640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livermore DM. Fourteen years in resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:283–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louie M, Cockerill FR., 3rd Susceptibility testing. Phenotypic and genotypic tests for bacteria and mycobacteria. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:1205–26. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanco M, Blanco JE, Blanco J, Gonzalez EA, Mora A, Prado C, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and other verotoxin-producing E. coli in healthy cattle. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:251–7. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falbo V, Famiglietti M, Caprioli A. Gene block encoding production of cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 and hemolysin in Escherichia coli isolates from extraintestinal infections. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2182–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2182-2187.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldenberg RI, Neter E. Meningitis due to two serotypes of Escherichia coli. An infant who recovered. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:213–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120150095020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bidet P, Mahjoub-Messai F, Blanco J, Blanco J, Dehem M, Aujard Y, et al. Combined multilocus sequence typing and O serogrouping distinguishes Escherichia coli subtypes associated with infant urosepsis and/or meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:297–303. doi: 10.1086/518897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siitonen A, Martikainen R, Ikaheimo R, Palmgren J, Makela PH. Virulence-associated characteristics of Escherichia coli in urinary tract infection: a statistical analysis with special attention to type 1C fimbriation. Microb Pathog. 1993;15:65–75. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video 1: HD6 Coronal brain MRI showing basal ganglia abscess.

Supplemental Video 2: HD13 Coronal brain MRI showing extensive leptomeningeal enhancement and uncal herniation.