Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide. COPD, however, is a heterogeneous collection of diseases with differing causes, pathogenic mechanisms, and physiological effects. Therefore a comprehensive approach to COPD prevention will need to address the complexity of COPD. Advances in the understanding of the natural history of COPD and the development of strategies to assess COPD in its early stages make prevention a reasonable, if ambitious, goal.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is, at present, the third leading cause of mortality worldwide.1 Prevention of COPD should be a major public health goal.2 Although this goal can be achieved to some extent by smoking cessation, smoking is not the only cause of COPD and additional preventive strategies are needed. Despite the public health importance of COPD prevention, relatively little is known about it. The diverse causes and pathogenic processes that lead to COPD mean that COPD is a heterogeneous collection of many different diseases that are grouped because of similar features. This is an issue for preventive efforts, which will probably need to be disease specific.

Definition of early COPD

Issues and challenges with the definition of COPD confound the definition of early COPD

The definition of early COPD is complicated by the issues relating to the definition of COPD itself and, more importantly, to the heterogeneity of its natural history. The key defining feature of COPD is post bronchodilator limitation of expiratory airflow by comparison with lung volumes.3,4 Expiratory airflow is usually measured as the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and lung volume as the forced vital capacity (FVC), both of which are readily assessed with spirometry, a simple non-invasive test. This simple definition, based on easily measured physiological variables, is very robust for epidemiological purposes. Although the physiological definition of COPD has the advantage of being objective, it has two important limitations.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched the full available range of articles on PubMed using the search terms “COPD” and “definition, evaluation, natural history” (search last updated on Feb 21, 2015). We selected articles published in English that addressed early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We further reviewed references cited in reviewed articles. We selected articles that informed the strategy for prevention of early COPD. The development of a research agenda to prevent COPD was the subject of a recent National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop and was also used in this regard.

The FEV1 cutoff point

The first issue for attempts to define early COPD is the use of a categorical definition. Airflow varies continuously within a population, and different FEV1:FVC ratio cutoff points have been used to define COPD.4,5 Moreover, across a population, both the FVC and the FEV1 reduce with age, but the FEV1 reduces more rapidly. As a result the FEV1:FVC ratio diminishes with age. Researchers debate whether this loss is merely age related, or represents pathology present in the general population. However, the changing ratio with age has led epidemiologists to prefer a statistically based age-specific lower limit of normal to define the cutoff point for COPD.5 Since this cutoff point is difficult to implement clinically, clinical guidelines usually use a fixed ratio of 0·7, with an FEV1:FVC ratio lower than that being the criterion to define COPD.4,6,7 Because of the age-related changes, the fixed ratio will under-diagnose COPD in younger individuals and over-diagnose COPD in older individuals (figure 1), which creates a particular difficulty when defining so-called early disease. This issue can make so-called mild disease difficult to separate from health.8

Figure 1. Effect of age on FEV1:FVC ratio and definition of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Diagram showing the loss of the lower limit of normal of FEV1:FVC ratio with ageing. The blue shaded portion represents elderly patients who are potentially overdiagnosed and the orange shaded portion represents younger adults who are potentially underdiagnosed with obstructive lung disease. FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 s. FVC=forced vital capacity. Reproduced from Mannino and colleagues,8 by permission of BMJ Publishing Group.

FEV1 can also be reduced in an individual without the FEV1:FVC ratio being reduced.9 Moreover, either emphysema or chronic bronchitis might be present in individuals with normal lung function and, if so, their outlook is not normal. Further complicating the definition of emphysema is the reduction in FVC that can result from several disorders including obesity.10,11 This dilemma makes mild COPD difficult to assess in these individuals with present definitions.

COPD heterogeneity

The second and more fundamental issue in the definition of early COPD is that COPD is heterogeneous histologically and pathogenically. Conventionally, COPD includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis, which might be present to varying degrees and affect spirometry differently.3,4 However, other disorders that can restrict expiratory airflow are excluded from the definition of COPD (panel 1). However, some of the excluded disorders—eg, bronchiectasis and tracheobronchial malacia—might be present in individuals with COPD, and whether they represent meaningful subsets of COPD is unknown. Whether to include patients with asthma who develop fixed airflow limitation within the definition of COPD has been controversial. The Venn diagram proposed by Snider12 (figure 2) presents graphically the idea that multiple disorders with or without airflow limitation might be present to varying degrees in different individuals. Whether the relation of bronchiectasis and tracheobronchial malacia with COPD should be regarded in a similar way to that of asthma is unresolved.

Panel 1. Causes of reduced airflow that are generally excluded from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Endobronchial or tracheal tumour

Endobronchial or tracheal stenosis

Tracheobronchial malacia

Obliterative bronchiolitis

Bronchiectasis

Cystic fibrosis

Other causes

Sarcoidosis

Eosinophilic granuloma

Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease

Asthma*

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. *Whether asthma should be excluded from the diagnosis of COPD has been controversial.

Figure 2. Subsets of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma can lead to fixed airflow limitation. The three disorders can overlap. All can be present without airflow limitation. This results in several (numbered) potential groups, which could be deemed subsets of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related disorders. Modified from Snider,12 by permission of the American Thoracic Society.

Several distinct causes and pathogenic processes might lead to limitation of airflow (panel 2). These heterogeneous risk factors make identification of early COPD challenging. Cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor and cause for COPD and some definitions of COPD have included smoking in the definition.6 However, other exposures, including indoor and outdoor air pollution, can cause COPD.13 Researchers increasingly recognise the importance of air pollution on lung function loss,14 particularly in the developing world,15 and various types of pollution might lead to COPD with different clinical features and natural histories than cigarette smoking.16,17 However, present estimates suggest that smoking accounts for only about half of the attributable risk for COPD in the developed world.18 In the USA, 20% of patients with COPD are non-smokers and smoking accounts for only part of the risk among smokers. The relative contribution to COPD due to asthma, air pollution, low maximum attained lung function, or unrecognised factors is unknown.

Panel 2. Processes that lead to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Poor lung development

Compromised intrauterine development

Reduced lung growth in childhood

Excess lung damage

Cigarette smoking

Air pollution

Viral infection

Airway remodelling

Asthma

Bronchitis

Deficient lung maintenance or repair

Cigarette smoking

Starvation

Ageing

The categories listed are designed to represent the heterogeneity of processes that can lead to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Many categories are themselves heterogeneous. Importantly, they can be present concurrently to varying degrees in individual patients. Consequently, many (if not most) patients with the disease have more than one process active.

Endogenous factors affect individual susceptibility to development of COPD. Genetic susceptibility to COPD is well recognised and several genes have been suggested to have roles.19,20 However, most genes that are associated with COPD account for only a small portion of risk and many interacting genes will probably contribute to individual susceptibility. Non-genetic factors such as early lung development21 and nutrition22 might also contribute to so-called endogenous susceptibility.

The many causes and susceptibility factors for COPD and their complex interactions imply that the syndrome of COPD is a composite of many disorders.23 However, the multiple subtypes of COPD probably will not be easily segregated into distinct diseases. Rather, most patients meeting spirometric criteria for COPD will have airflow limitation as a result of several processes, each with a distinct natural history. Early COPD will have to be recognised and addressed in the context of this complexity.

Challenges of identifying early COPD

Distinguishing early from mild disease

Whereas the definition of COPD has engendered much discussion, the definition of early COPD has not. Early implies a time in the natural history of COPD, either before the disease is present or a time when the disease has not progressed to full clinical effect. As such, early contrasts with mild COPD. Most of the studies of COPD have many participants aged greater than 60 years. Many of these participants have so-called mild disease, which might have been present for decades, and represents so-called late, mild disease. This late, mild disease should not be confused with so-called early disease. The concept of early disease necessitates an understanding of disease natural history.

Lung health and COPD natural histories

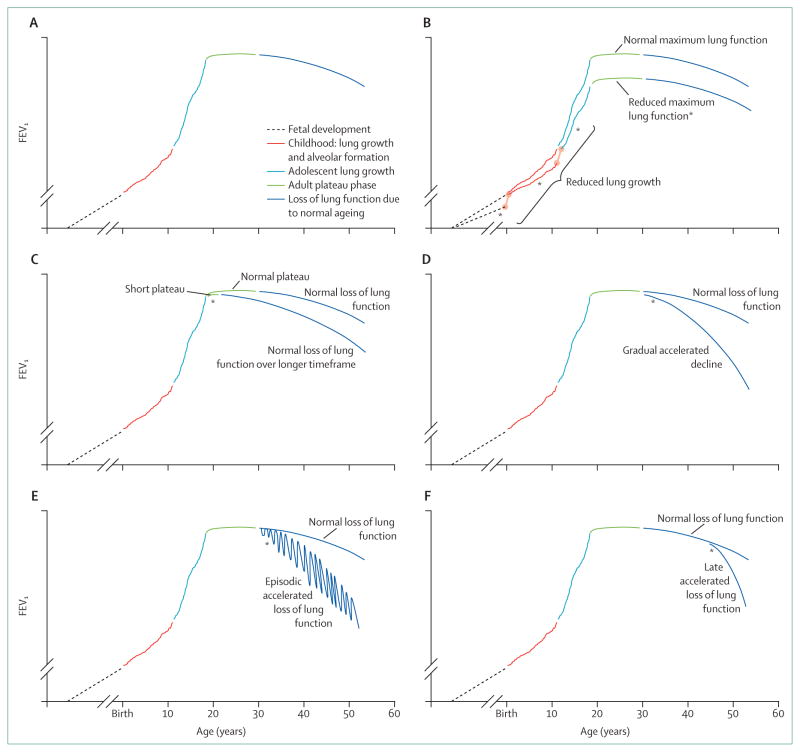

Pathogenic processes leading to COPD can happen at any time of life and COPD natural histories can reasonably be viewed in the context of overall lung health.24 Airway branching is completed by the 17th week of gestation. Airways increase in length and diameter until young adulthood, but, generally, new airways do not form. Alveoli develop by a separate process and are present at birth, increasing during childhood through secondary alveolar wall formation.25 Lung volume and airflow continue to increase as the thorax grows, reaching a peak in young adulthood (about 20 years of age) (figure 3A). In healthy individuals, lung function then plateaus for about 10 years, after which lung function is gradually lost. Whether this loss is so-called normal ageing or represents a pathological process remains undefined.

Figure 3. Natural history of lung function and development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

(A) Normal lung function natural history. (B) Reduced lung growth during fetal development, childhood, or adolescence (which might be independent), any of which can reduce attained lung function. (C) Shortened plateau. (D) Accelerated lung function loss during adulthood. (E) Episodic loss of lung function without full recovery. (F) Late accelerated loss of lung function. FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 s. *Presence of early disease for each disease natural history.

Early life events and COPD

Barker and colleagues21 showed that early life events leading to low birthweight increase COPD risk. The effect of being born small (<5 lb vs >10 lb [<2·3 kg vs 4·5 kg]) was similar in magnitude to being an ever smoker for COPD risk. What the intrauterine events are that lead to COPD risk are not fully understood, but, in addition to birthweight, prematurity,26 maternal smoking,27,28 and maternal nutrition2 have all been suggested as risk factors. A multifactorial pathogenesis is supported by the idea that reduced early life lung function itself is associated with reduced lung function in early adulthood (aged about 20–25 years).29 Although the mechanisms remain to be established, these early life events might represent early COPD. When lung development is compromised, maximum attained lung growth is reduced and the risk of COPD is increased (figure 3B).

Childhood and adolescent lung growth

Disorders that compromise lung growth during childhood and adolescence can also increase COPD risk. A presumed mechanism for this occurrence is that impaired lung growth and development leads to reduced maximum attained lung function, which is a risk factor for the development of COPD (figure 3B). Cigarette smoke is a risk to lung health at these ages as well. Active smoking during childhood and adolescence compromises lung growth.30–32 Passive smoking in childhood, independent of maternal smoking during pregnancy, is associated with reduced maximum attained lung function, although differences in susceptibility between men and women have been suggested.28 Prematurity might also affect maximum attained lung function, as does low birthweight.21,26,33 The presence of airways reactivity and blood eosinophilia, presumably linked to asthma or related processes, is associated with reduced maximum attained lung function, as is the presence of respiratory symptoms.32 Although controversial, some studies21,34–36 suggest that childhood infections could compromise the development of lung function and increase risk of development of COPD. Similarly, lung function growth is compromised in children who developed bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and these individuals are at particular risk of developing airflow limitation.26,33 Whether altered lung development and growth from other disorders also leads to accelerated lung function loss in adulthood is unknown.

Plateau phase

After lung growth ceases in young adulthood (aged about 20–25 years), lung function remains close to constant for about 10 years. Lung function then slowly decreases.37,38 Cigarette smoking shortens the duration of the so-called plateau phase of lung function.37,39 Since cigarette smoking causes the loss of lung function associated with ageing to start at an earlier age, a shortened plateau phase leads to lower age-adjusted lung function and increases the risk of development of COPD (figure 3C). Little is known about the mechanisms for the shortened plateau phase, including whether the mechanisms are distinct from the mechanisms that cause accelerated lung function loss. Additionally, whether factors other than cigarette smoking affect the plateau phase is also not known.

Accelerated loss of lung function

The idea that smokers lose lung function at an accelerated rate (about twice that of non-smokers) was lent support by the landmark study by Fletcher and colleagues40,41 and has been substantiated. The studies’ results40,41 show that susceptibility to smoke is variable and that a portion of smokers will develop symptomatic COPD. Subsequent studies42,43 have suggested that about half of smokers will eventually meet the threshold for a COPD diagnosis. Importantly, the magnitude of the accelerated lung function loss might not be constant over time. Several studies44,45 have suggested that the loss of lung function of individuals with moderate COPD progresses more rapidly than in those with more severe COPD. What the rate of lung function loss is in early COPD remains unknown.46

The way by which smoking accelerates loss of lung function, however, is complex because many pathogenic processes are initiated by smoke. This complexity might lead to differing natural histories as well. Burrows47 suggested three ways for lung function to decrease: gradually, at an accelerated rate throughout adult life (figure 3D); episodically, perhaps related to acute exacerbations (figure 3E); or a phase of rapid progression could develop after a period of so-called normal ageing (figure 3F). Exposures in addition to cigarette smoke can accelerate lung function loss, including air pollution and occupational dusts and fumes.13–15,48,49 Starvation can lead to the development of emphysema.50,51 Other nutritional factors have also been associated with COPD risk,22 although whether these lead to accelerated lung function loss remains undefined.

Interactions among natural histories

Although much remains unknown about the mechanisms that lead to the reduced lung function in COPD, several distinct processes can contribute and these probably synergise. Moreover, some causes of COPD (eg, cigarette smoking) can affect lung function in different ways at different times in the lifecycle. The concept of early COPD will need to integrate these diverse processes.

Natural history beyond FEV1

Airflow limitation is used to define COPD, but it only partly captures the clinical features of COPD. Cough and sputum probably result from airways metaplasia, inflammation, and glandular hyperplasia.3,4 Dyspnoea in COPD is mostly due to dynamic hyperinflation.52,53 The extrapulmonary features that are characteristic of COPD are relatively independent of FEV1, and are often the major clinical problems patients face.54–56 Moreover, extrapulmonary problems might be present when FEV1 compromise is mild, suggesting these comorbidities might be particularly relevant for the assessment of early disease. In support of this theory, most of the increased risk for cardiac disease associated with COPD occurs with very mild limitation of FEV1 and is present even with FEV1 levels in low levels of the healthy range.57 Additionally, very reduced activity levels are present in patients with mild COPD,58–60 and muscle weakness often restricts exercise capacity rather than airflow.61–63 Whether these comorbidities should be regarded as extrapulmonary manifestations or as separate diseases is unclear. However, each of these comorbidities will have so-called early phases that might be appropriate for intervention, and these could precede the development of FEV1 compromise.

Summary of challenges for the definition of early COPD

Early COPD means an interval in time at the beginning of the disease course. This early phase could occur in late life—for example, in an individual who has had a natural history of healthy lung function but who has entered a period of very rapid loss of lung function. Alternatively, early COPD could happen in mid or very early life. Since several pathogenic processes could be active in the same individual, these processes can be early at different times in the individual. Finally, COPD is defined in terms of severity of airflow limitation. The disease process that leads to airflow limitation could be active at a time when lung function is healthy. Whether such a person should be deemed healthy or not seems less important than recognition of whether the individual has a process that needs attention.

Assessment of early COPD

Lung function

Several diagnostic tests could define early COPD (panel 3). Spirometry is the most widely used method to assess lung function. The test is well understood, is readily available, is used to assess the prevalence and severity of COPD, and can be practised in various settings and in children aged 3–5 years and older.64–67 Spirometry could be used to diagnose early COPD, but the diagnosis is likely to need sequential measures. One test, for example, can define so-called mild COPD, but whether the disease is newly incident or has been present for many years might be difficult to establish. Longitudinal use of spirometry, therefore is needed to diagnose so-called early disease.

Panel 3. Potential measures of disease progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physiology

Airflow

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

Impedance oscillometry

Lung volume

Inspiratory capacity

Dynamic hyperinflation

Other

Diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

-

Exercise capacity

Maximum oxygen consumption

Submaximum constant work rate endurance time

Lung clearance index

Imaging

CT scan

-

Emphysema

Global severity

Pattern

Airways

Vasculature

Magnetic resonance imaging

Performance

6 min walk test

Activity measures

Health status

SGRQ

CAT

Short Form (36) Health Survey

SGRQ=St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. CAT=COPD Assessment Test.

Several large longitudinal studies40,41,44,45,68 have established rates of loss of lung function for non-smokers, smokers, and individuals with established COPD. The presence of rapid loss of FEV1 in individuals with healthy lung function is therefore a feasible strategy to identify early disease. Identification of natural histories with other trajectories—eg, reduced lung growth or reduced plateau phase—is also feasible to identify early disease.30–32,37,38 Routine sequential measures of spirometry have the potential to identify early COPD, but are not used routinely at present to monitor for the development of disease. Present management of patients with cystic fibrosis shows that sequential measures of spirometry are clinically feasible and that the values obtained can suggest changes in disease natural history.69 A similar strategy could probably be used to assess early COPD.

In addition to spirometry, other measures of lung function might have potential to detect early COPD.66 The lung clearance index captures the heterogeneity of small airways function and seems to be more sensitive to early lung function compromise in cystic fibrosis than spirometry.70,71 The usefulness of the lung clearance index in COPD is not established. Similarly, impedance oscillometry, which assesses airways resistance and capacitance and is effort independent, might be particularly useful in sequential assessment of patients with COPD.72–74 Impedance oscillometry has been reported to be abnormal in patients with pulmonary symptoms with FEV1 in the healthy range, and thus might have potential to detect early COPD.75 The diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide is reduced in emphysema.64 The test’s potential for detecting early disease or disease progression, however, is deemed to be limited by variance in the test itself and difficulties in calibration of the measures across centres.

Exercise performance or dynamic hyperinflation

Although limitation of expiratory airflow is the defining feature of COPD, the compromise of lung volume is what causes dyspnoea and frequently restricts exercise.52,53 Specifically, the lungs might not have adequate time to empty because of the limitation in expiratory flow as respiratory rate increases. This restriction of the lungs’ ability to empty results in air from one inspiration being trapped in the lung when the next inspiration begins. As a result, the lungs can become progressively hyperinflated as a function of respiratory rate—hence the term dynamic hyperinflation. This problem leads to dyspnoea, possibly due to the increased work needed to breathe at increased lung volumes. Dynamic hyperinflation is related not only to overall airflow limitation, measured by the FEV1, but also to the heterogeneity of airflow within the lung.76 Consequently, dynamic hyperinflation might be a more sensitive measure of disease severity than FEV1 in mild COPD. Whether assessment of dynamic hyperinflation could be used to assess early COPD remains untested. Present methods need specialised laboratories and the tests are not well suited for multiple repeat measures. Nevertheless, dynamic hyperinflation or ventilation, or both, measured during exercise, might be able to identify the presence of early COPD.

Imaging

By contrast with the routine chest radiograph, which is abnormal only with relatively severe emphysema, CT has tremendous potential to assess early COPD.2,77,78 The CT scanner is fundamentally a densitometer, deter mining the radiographic density of three-dimensional voxels of the imaged tissue. The resolution of present instruments results in cubic voxels of about 0·75 mm per side. Images, which are used for routine clinical interpretation, are reconstructed from the density data. The data, however, are ideally suited to generate quantitative assessments and methods have been developed to assess both emphysema and airways disease.79–81

The lost lung tissue in emphysema is replaced by empty airspace, resulting in a substantial decrease in radiographic density that is quantifiable by the CT scan. Several consensus meetings have addressed technical issues, including comparison of variables to assess emphysema and normalisation of data to lung volume and normal ranges. The clinical validity of CT measures has been assessed in studies79–82 that have validated overall lung density, a measure of total emphysema.

Techniques have also been developed to assess the pattern of emphysema that can be quantitated by the CT scan. Specific clinical correlations have been shown with upper lobe versus lower lobe predominant disease,83 and patterns of emphysema, including centrilobular, diffuse and paraseptal, have been suggested to be distinct clinical phenotypes. Changes in lung volumes have been associated with mild COPD, although physiological measures to assess these have had restricted use.84 Comparison of inspiratory and expiratory scans can identify local air trapping, which could be a particularly sensitive measure of volume changes present in mild disease.78

Substantial emphysema can be present in individuals with mild airflow limitation or with airflow that is within the generally accepted spirometric healthy range. So far, no systematic studies assessing the use of CT scans to detect early emphysema have been done; these studies would need to assess quite young individuals sequentially over time. However, the Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study85 could provide such data in the near future. Sequential CT studies82,86 have been done in patients with α 1 antitrypsin deficiency associated emphysema and patients with cigarette smoke associated emphysema, and the ability of CT scan to assess disease progression seems to be at least similar to that of spirometry. Registration methods have been described within the past few years that can assess density changes in spatially defined regions over time that might substantially improve the assessment of changes over time.87

Airways can also be assessed by CT scan and several measures have been proposed.79–81 These measures include assessment of airways thickness and airways number. However, less consensus exists on the best way to assess airways than exists for the assessment of alveolar structures.88 Nevertheless, airways disease, assessed as wall thickness, has been related to exacerbation risk,89 suggesting wall thickness is a clinically valid measure. The use of CT measured airways variables to assess early COPD is mostly untested.

Other imaging modalities also have potential to assess early emphysema. Hyperpolarised magnetic resonance imaging can provide a measure of alveolar size by estimating gas diffusion distance. This method allows quantification of alveolar enlargement90 and has also been used to track alveolar growth.91 Gas diffusion can be quantified with spatial orientation, which can estimate small airway size.92 Finally, specialised methods allow assessment of pulmonary vasculature,93 which might be particularly important because emphysema is characterised by loss of pulmonary capillary bed. Although these methods are still in the investigational stage, they offer promising novel means to assess the lung and have great promise in the assessment of early COPD.

Clinical features

The present definition of chronic bronchitis—cough or sputum, or both, present on most days for 3 consecutive months in 2 consecutive years—was adopted as a temporary working definition in 1962 because no more precise consensus could be reached.94 No satisfactory replacement has emerged so far. Because cough and sputum are readily assessed by history, the presence of chronic bronchitis can be assessed by questionnaire. Several instruments have been developed for this purpose and general respiratory symptom questionnaires that include cough and sputum questions have been used as well.95–98 As noted previously, chronic bronchitis can be present without airflow limitation.3 When present, chronic bronchitis is associated with poorer health status and worse prognosis—including a greater likelihood of developing airflow limitation—than when it is absent.97,99–101 Whether individuals with chronic bronchitis without airflow limitation should be regarded as having early COPD or as being at risk of developing COPD is unresolved, but symptoms of cough, sputum, and dyspnoea have been associated with subsequent incident COPD.99

Patients with COPD manifest several characteristic extrapulmonary features. Prominent among these features is a substantially reduced level of physical activity.58–60 Physical activity can be assessed by questionnaires and by monitors that are sensitive to movement. In 2013, a combined questionnaire and monitor approach was developed for use in patients with COPD.102,103 Because substantially reduced levels of activity might be present in mild COPD, activity measures would probably be useful for the assessment of early COPD. Whether other extra pulmonary morbidities associated with COPD will be useful in the assessment of early COPD remains largely untested.

Health status measures

Patients with COPD have impaired health status, and several validated disease-specific104,105 and general measures106 have been widely used in clinical studies. Importantly, health status measures correlate with airflow limitation (although only poorly), suggesting that health status measures capture different features of the clinical experience compared with spirometry.107 Health status measures are also abnormal in smokers with normal airflow, suggesting that these measures could be used to assess early COPD.108,109

Biomarkers of disease progression

COPD is associated with inflammation of the lungs. Cigarette smoke and many other COPD risk factors lead to inflammation, which is thought to have a pathogenic role in the development of COPD. However, as yet, neither measures of inflammation nor other biomarkers can identify individuals with lung function in the healthy range who will develop COPD. Nevertheless, this is a promising area of continuing research.3,4

Prevention of early COPD

Types of prevention

Prevention can be classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary. Prevention of disease development in people who are still well is primary prevention. Prevention of clinically apparent disease in people with detectable abnormalities is secondary prevention. Prevention of disease progression in people with clinically apparent disease is tertiary prevention. However, in the context of early COPD, these distinctions are often difficult because of the complex and heterogeneous natural history of COPD, the arbitrary selection of so-called cutoff points separating disease from normal, and the imprecise definition of when disease starts. Nevertheless, several potential strategies for prevention have been developed, and excellent evidence exists that prevention is an achievable goal.

Of the many causes of COPD, cigarette smoking is by far the most important. Smoking cessation or prevention can lead to primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. If achieved early enough, smoking cessation reduces the incidence of respiratory morbidity and incident COPD.110 The Lung Health Study (LHS)111 showed secondary prevention by prospectively assessing the effect of smoking cessation on the progression of FEV1 loss in a group of individuals with mild COPD, and these results have been substantiated in the observational Framingham study,112 which also showed tertiary prevention. The mean age of LHS participants was 48 years, therefore in most of these participants the disease processes leading to COPD had probably been present for decades. However, disease was mild and was early in the sense that its progression was mitigated by smoking cessation.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention strategies are appealing, but can be difficult to assess. Identification of modifiable risk factors for COPD has suggested strategies to mitigate the risk.24 However, the mechanistic basis for the associations between risk factors and disease is generally not understood. Whether correction of risk factors will reduce disease incidence, therefore, has to be assessed empirically. This assessment is somewhat daunting because interventions might need to begin with pregnancy to prevent disease being present six decades later. However, the associations between lung growth and development, maximum attained lung function in young adulthood (aged about 20–25 years), and the development of COPD suggest intermediate endpoints might exist that could be assessed in trials of prevention.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention requires the ability to detect early disease before it is clinically apparent. LHS showed that spirometry can be successfully used to assess smoking cessation as a preventive measure for COPD progression.111

Tertiary prevention

Several studies68,111,113 suggest that disease progression can be slowed in established COPD. In the TORCH study,68 spirometry also showed significantly reduced progression with fluticasone proprionate (13 mL/year), salmeterol (13 mL/year), and the combination (16 mL/year) compared with placebo, although these differences are less than the generally accepted clinical target of 20 mL/year. The UPLIFT study113 reported no significant difference in lung function loss between patients given tiotropium versus placebo. However, among individuals with moderate disease (FEV1 56% predicted), the rate of FEV1 loss of those given tiotropium was 6 mL less than that of the controls.113 Although not tested for primary or secondary prevention, these findings suggest that, as with smoking cessation, pharmacological interventions could be more effective in early disease than in late disease.

Studies such as the LHS,111 TORCH,68 and UPLIFT113 are large, with several thousand participants. However, participant selection could improve the efficiency of prevention studies. As noted previously, the rate of loss of lung function in patients with COPD is highly variable. Inclusion of those patients with COPD more likely to rapidly lose their lung function could substantially reduce the size and, possibly, the duration of prevention studies.

A different approach will be necessary to identify early COPD due to so-called life trajectories different from accelerated loss of lung function (figure 3). Stratification of participants for prevention studies on the basis of their natural history will be particularly important for interventions that are specific for pathogenic mechanisms present in only a portion of the population. Validation of diagnostic biomarkers that can stratify individuals appropriately will be necessary for these highly focused approaches.

Measures other than spirometry have the potential not only to assess disease progression but also to identify subtypes of patients with COPD. Thus, identification of individuals with emphysema (by CT scan), chronic bronchitis (by history), airways reactivity (by methacholine challenge), or decreased physical activity levels could be candidates for interventions designed to prevent both the progression of the diagnostic feature and the development of fixed airflow limitation.

Other quantitative measures of disease severity in COPD, including dynamic hyperinflation, exercise performance, activity levels, health status, and comorbidities might also provide adequate measures of disease progression for secondary prevention interventions. In view of the complexities of COPD pathogenesis and the heterogeneity of its natural histories, some interventions will probably mitigate progression of some aspects of COPD but not others. Thus, the ability to identify subsets of patients with COPD and to quantify multiple dimensions of disease progression could prove particularly important.

Conclusion

COPD is a major worldwide public health issue. Efforts to control cigarette smoking will have a major effect on COPD prevention. However, smoking is not the only risk factor for COPD and additional preventive efforts are needed. The ability to assess disease progression combined with an understanding of the complex and heterogeneous natural histories of COPD throughout the entire life cycle is creating novel opportunities for preventive interventions, which might need to be selective for specific types of COPD.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by Lillian Richards with the formatting and submission of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors

SIR and MBD conceptualised the Series paper, selected the information to be included, and drafted the Series paper.

Declaration of interests

Since 2012, SIR has received honoraria, consultation fees or research funding from the American Board of Internal Medicine, Almirall, APT Pharma, the American Thoracic Society, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Boerhinger Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, the Cleveland Clinic, the COPD Foundation, CSA, CSL, the California Thoracic Society, Daiichi Sankyo, Elevation Pharma, Forest, GSK, Gilead, Johnson & Johnson, MedImmune, Novartis, Pearl, Pfizer, Pulmatrix, Regeneron, Takeda, Theron, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. MBD has no relevant financial competing interests related to this Series paper. MBD has served as a consultant for Lupin Pharmaceuticals and has received institutional grant funding from the National Institutes of Health for studies related to COPD.

Contributor Information

Prof. Stephen I Rennard, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA.

M Bradley Drummond, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

References

- 1.WHO. [accessed Feb 14, 2015];The top 10 causes of death. 2014 May; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/

- 2.Drummond MB, Buist AS, Crapo JD, Wise RA, Rennard SI. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: NHLBI workshop on the primary prevention of chronic lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(suppl 3):S154–60. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-432LD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro SD, Reilly JJJ, Rennard SI. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema. In: Robert J, Mason RJ, Martin TR, et al., editors. Textbook of respiratory medicine. 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010. pp. 919–67. [Google Scholar]

- 4. [accessed Feb 14, 2015];Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2015 http://www.goldcopd.org/

- 5.Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, et al. Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax. 2008;63:1046–51. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.098483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomashow B, Crapo J, Yawn B, et al. The COPD foundation pocket consultant guide. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1:83–87. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.1.1.2014.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannino DM, Sonia Buist A, Vollmer WM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the older adult: what defines abnormal lung function? Thorax. 2007;62:237–41. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.068379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan ES, Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, et al. the COPDGene Investigators. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir Res. 2014;15:89. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0089-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannino DM, Ford ES, Redd SC. Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and functional limitation: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination. J Intern Med. 2003;254:540–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2003.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soriano JB, Miravitlles M, Garcia-Rio F, et al. Spirometrically-defined restrictive ventilatory defect: population variability and individual determinants. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:187–193. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snider GL. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a definition and implications of structural determinants of airflow obstruction for epidemiology. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:S3–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3_Pt_2.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buist AS, Vollmer WM. Smoking and other risk factors. In: Murray JF, Nadel JA, editors. Textbook of respiratory medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1994. pp. 1259–87. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs SH, Schindler C, Liu LJ, et al. the SAPALDIA Team. Reduced exposure to PM10 and attenuated age-related decline in lung function. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2338–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramírez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, Quintana-Carrillo RH, et al. FEV1 decline in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with biomass exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:996–1002. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0720OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camp PG, Ramirez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, et al. COPD phenotypes in biomass smoke- versus tobacco smoke-exposed Mexican women. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:725–34. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00206112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet. 2007;370:765–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho MH, McDonald ML, Zhou X, et al. the NETT Genetics, ICGN, ECLIPSE and COPDGene Investigators. Risk loci for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a genome-wide association study and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:214–25. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, Cohn M, et al. The COPD genetic association compendium: a comprehensive online database of COPD genetic associations. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:526–34. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barker DJP, Godfrey KM, Fall C, Osmond C, Winter PD, Shaheen SO. Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ. 1991;303:671–75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6804.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanson C, Rutten EP, Wouters EF, Rennard S. Influence of diet and obesity on COPD development and outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:723–33. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S50111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rennard SI, Vestbo J. The many “small COPDs”: COPD should be an orphan disease. Chest. 2008;134:623–27. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camargo CA, Jr, Budinger GR, Escobar GJ, et al. Promotion of lung health: Nhlbi workshop on the primary prevention of chronic lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(suppl 3):S125–38. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-451LD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon JM, Greenberf JM. Lung growth and development. In: Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin TR, et al., editors. Textbook of respiratory medicine. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotecha SJ, Edwards MO, Watkins WJ, et al. Effect of preterm birth on later FEV1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2013;68:760–66. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beyer D, Mitfessel H, Gillissen A. Maternal smoking promotes chronic obstructive lung disease in the off spring as adults. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14(suppl 4):27–31. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-S4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svanes C, Omenaas E, Jarvis D, Chinn S, Gulsvik A, Burney P. Parental smoking in childhood and adult obstructive lung disease: results from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Thorax. 2004;59:295–302. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.009746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern DA, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Guerra S, Martinez FD. Poor airway function in early infancy and lung function by age 22 years: a non-selective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:758–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold DR, Wang X, Wypij D, Speizer FE, Ware JH, Dockery DW. Effects of cigarette smoking on lung function in adolescent boys and girls. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:931–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Wypij D, Gold DR, et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of parental smoking on pulmonary function in children 6–18 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1420–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Mensinga TT, Schouten JP, Rijcken B, Weiss ST. Determinants of maximally attained level of pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:941–49. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2201011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vollsæter M, Røksund OD, Eide GE, Markestad T, Halvorsen T. Lung function after preterm birth: development from mid-childhood to adulthood. Thorax. 2013;68:767–76. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colom AJ, Maffey A, Garcia Bournissen F, Teper A. Pulmonary function of a paediatric cohort of patients with postinfectious bronchiolitis obliterans. A long term follow-up Thorax. 2015;70:169–74. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edmond K, Scott S, Korczak V, et al. Long term sequelae from childhood pneumonia; systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Marco R, Accordini S, Marcon A, et al. the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) Risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a European cohort of young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:891–97. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1125OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tager IB, Segal MR, Speizer FE, Weiss ST. The natural history of forced expiratory volumes. Effect of cigarette smoking and respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:837–49. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherrill DL, Lebowitz MD, Knudson RJ, Burrows B. Continuous longitudinal regression equations for pulmonary function measures. Eur Respir J. 1992;5:452–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherrill DL, Lebowitz MD, Knudson RJ, Burrows B. Smoking and symptom effects on the curves of lung function growth and decline. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:17–22. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ. 1977;1:1645–48. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fletcher C, Peto R, Tinker C, Speizer F. The natural history of chronic bronchitis and emphysema. New York: Oxford University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rennard SI, Vestbo J. COPD: the dangerous underestimate of 15% Lancet. 2006;367:1216–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burrows B, Knudson RJ, Cline MG, Lebowitz MD. Quantitative relationships between cigarette smoking and ventilatory function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115:195–205. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vestbo J, Edwards LD, Scanlon PD, et al. the ECLIPSE Investigators. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1184–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. the UPLIFT Study Investigators. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance—United States, 1971–2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burrows B. An overview of obstructive lung diseases. Med Clin North Am. 1981;65:455–71. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz J. Lung function and chronic exposure to air pollution: a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES II. Environ Res. 1989;50:309–21. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(89)80012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman EK, Speizer FE. Risk factors for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Clin North Am. 1996;80:501–22. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70451-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stein J, Fenigstein H. Anatomie pathologique de la maladie de famine. In: Apfelbaum E, editor. Maladie de famine. Warsaw, Poland: American Joint Distribution Committee; 1946. pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coxson HO, Chan IH, Mayo JR, Hlynsky J, Nakano Y, Birmingham CL. Early emphysema in patients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:748–52. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-651OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Donnell DE, Banzett RB, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. Pathophysiology of dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a roundtable. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:145–68. doi: 10.1513/pats.200611-159CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chin RC, Guenette JA, Cheng S, et al. Does the respiratory system limit exercise in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1315–23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1970OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghe B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:204–12. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barr RG, Celli BR, Mannino DM, et al. Comorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPD. Am J Med. 2009;122:348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mannino DM, Braman S. The epidemiology and economics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:502–06. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-001FM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sin DD, Wu L, Man SF. The relationship between reduced lung function and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based study and a systematic review of the literature. Chest. 2005;127:1952–59. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Troosters T, Sciurba F, Battaglia S, et al. Physical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-study. Respir Med. 2010;104:1005–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Remoortel H, Hornikx M, Langer D, et al. Risk factors and comorbidities in the preclinical stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:30–38. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1240OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Remoortel H, Hornikx M, Demeyer H, et al. Daily physical activity in subjects with newly diagnosed COPD. Thorax. 2013;68:962–63. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saey D, Debigare R, LeBlanc P, et al. Contractile leg fatigue after cycle exercise: a factor limiting exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:425–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-856OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gea J, Agustí A, Roca J. Pathophysiology of muscle dysfunction in COPD. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;114:1222–34. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00981.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vogiatzis I, Zakynthinos S. The physiological basis of rehabilitation in chronic heart and lung disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115:16–21. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00195.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Pulmonary function testing. In: Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin TR, et al., editors. Textbook of respiratory medicine. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 522–53. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. the ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beydon N, Davis SD, Lombardi E, et al. the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Working Group on Infant and Young Children Pulmonary Function Testing. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1304–45. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-642ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Redlich CA, Tarlo SM, Hankinson JL, et al. the American Thoracic Society Committee on Spirometry in the Occupational Setting. Official American Thoracic Society technical standards: spirometry in the occupational setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:983–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0337ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, et al. Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:332–38. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1869OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Shoseyov D, Kerem E. Managing cystic fibrosis: strategies that increase life expectancy and improve quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1463–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201009-1478CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aurora P, Stanojevic S, Wade A, et al. the London Cystic Fibrosis Collaboration. Lung clearance index at 4 years predicts subsequent lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:752–58. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1646OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gustafsson PM, Aurora P, Lindblad A. Evaluation of ventilation maldistribution as an early indicator of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:972–79. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00049502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Timmins SC, Coatsworth N, Palnitkar G, et al. Day-to-day variability of oscillatory impedance and spirometry in asthma and COPD. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;185:416–24. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Timmins SC, Diba C, Schoeffel RE, Salome CM, King GG, Thamrin C. Changes in oscillatory impedance and nitrogen washout with combination fluticasone/salmeterol therapy in COPD. Respir Med. 2014;108:344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kitaguchi Y, Fujimoto K, Hanaoka M, Honda T, Hotta J, Hirayama J. Pulmonary function impairment in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema with and without airflow obstruction. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:805–11. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S65621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frantz S, Nihlén U, Dencker M, Engström G, Löfdahl CG, Wollmer P. Impulse oscillometry may be of value in detecting early manifestations of COPD. Respir Med. 2012;106:1116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Niewoehner D. Structure-function relationships: the pathophysiology of airflow obstruction. In: Stockley R, Rennard S, Rabe K, Celli B, editors. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Malden: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wan ES, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, et al. the COPDGene Investigators. Clinical and radiographic predictors of GOLD-unclassified smokers in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:57–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0021OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hersh CP, Washko GR, Estépar RS, et al. the COPDGene Investigators. Paired inspiratory-expiratory chest CT scans to assess for small airways disease in COPD. Respir Res. 2013;14:42. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grydeland TB, Thorsen E, Dirksen A, et al. Quantitative CT measures of emphysema and airway wall thickness are related to D(L)CO. Respir Med. 2011;105:343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grydeland TB, Dirksen A, Coxson HO, et al. Quantitative computed tomography measures of emphysema and airway wall thickness are related to respiratory symptoms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:353–59. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1008OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rutten EP, Grydeland TB, Pillai SG, et al. Quantitative CT: associations between emphysema, airway wall thickness and body composition in COPD. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:419328. doi: 10.1155/2011/419328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stockley RA, Parr DG, Piitulainen E, Stolk J, Stoel BC, Dirksen A. Therapeutic efficacy of α-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy on the loss of lung tissue: an integrated analysis of 2 randomised clinical trials using computed tomography densitometry. Respir Res. 2010;11:136. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holme J, Stockley RA. Radiologic and clinical features of COPD patients with discordant pulmonary physiology: lessons from alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Chest. 2007;132:909–15. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodarte JR, Hyatt RE, Rehder K, Marsh HM. New tests for the detection of obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1977;72:762–68. doi: 10.1378/chest.72.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7:32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coxson HO, Dirksen A, Edwards LD, et al. The presence and progression of emphysema in COPD as determined by CT scanning and biomarker expression: a prospective analysis from the eclipse study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:129–36. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boes JL, Hoff BA, Bule M, et al. Parametric response mapping monitors temporal changes on lung CT scans in the subpopulations and intermediate outcome measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS) Acad Radiol. 2015;22:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith BM, Hoffman EA, Rabinowitz D, et al. the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) COPD Study and the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcomes in COPD Study (SPIROMICS) Comparison of spatially matched airways reveals thinner airway walls in COPD. Thorax. 2014;69:987–96. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Han MK, Kazerooni EA, Lynch DA, et al. the COPDGene Investigators. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in the COPDGene study: associated radiologic phenotypes. Radiology. 2011;261:274–82. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Woods JC, et al. Quantification of lung microstructure with hyperpolarized 3He diffusion MRI. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;107:1258–65. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00386.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Narayanan M, Owers-Bradley J, Beardsmore CS, et al. Alveolarization continues during childhood and adolescence: new evidence from helium-3 magnetic resonance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:186–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1348OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Leawoods JC, et al. Quantitative in vivo assessment of lung microstructure at the alveolar level with hyperpolarized 3He diffusion MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3111–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052594699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Easley RB, Fuld MK, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Hoffman EA, Simon BA. Mechanism of hypoxemia in acute lung injury evaluated by multidetector-row CT. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:916–21. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.American Thoracic Society. Chronic bronchitis, asthma and pulmonary emphysema. A statement by the Committee on Diagnostic Standards for Nontuberculous Respiratory Diseases. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1962;85:762–68. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Leidy NK, Rennard SI, Schmier J, Jones MK, Goldman M. The breathlessness, cough, and sputum scale: the development of empirically based guidelines for interpretation. Chest. 2003;124:2182–91. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leidy NK, Wilcox TK, Jones PW, et al. the EXACT-PRO Study Group. Development of the exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease tool (exact): a patient-reported outcome (pro) measure. Value Health. 2010;13:965–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim V, Crapo J, Zhao H, et al. Comparison between an alternative and the classic definition of chronic bronchitis in COPDgene. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:332–39. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-518OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Pavord ID. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) Thorax. 2003;58:339–43. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Probst-Hensch NM, Curjuric I, Pierre-Olivier B, et al. Longitudinal change of prebronchodilator spirometric obstruction and health outcomes: results from the SAPALDIA cohort. Thorax. 2010;65:150–56. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.115063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bradburne RM, Ettensohn DB, Opal SM, McCool FD. Relapse of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the upper lobes during aerosol pentamidine prophylaxis. Thorax. 1989;44:591–93. doi: 10.1136/thx.44.7.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Janson C, Marks G, Buist S, et al. The impact of COPD on health status: findings from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1472–83. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00153712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dobbels F, de Jong C, Drost E, et al. the PROactive consortium, and the PROactive consortium. The PROactive innovative conceptual framework on physical activity. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1223–33. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00004814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rabinovich RA, Louvaris Z, Raste Y, et al. the PROactive Consortium. Validity of physical activity monitors during daily life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1205–15. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George’s respiratory questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85(suppl B):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. discussion 33–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:648–54. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wyrwich KW, Fihn SD, Tierney WM, Kroenke K, Babu AN, Wolinsky FD. Clinically important changes in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an expert consensus panel report. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:196–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jones PW. Issues concerning health-related quality of life in COPD. Chest. 1995;107(suppl):187S–93S. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5_supplement.187s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ferrer M, Villasante C, Alonso J, et al. Interpretation of quality of life scores from the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:405–13. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00213202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maleki-Yazdi MR, Lewczuk CK, Haddon JM, Choudry N, Ryan N. Early detection and impaired quality of life in COPD GOLD stage 0: a pilot study. COPD. 2007;4:313–20. doi: 10.1080/15412550701595740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.US Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General and Office on Smoking and Health. A report of the surgeon general. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service, Office on Smoking and Health; 1990. The health benefits of smoking cessation. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA. 1994;272:1497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kohansal R, Martinez-Camblor P, Agustí A, Buist AS, Mannino DM, Soriano JB. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited: an analysis of the Framingham off spring cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:3–10. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0047OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Lystig T, Mehra S, Tashkin DP the UPLIFT investigators. Effect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1171–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]