Visual Overview

Keywords: anxiety, Cav, neurogenesis, neuroprotection, P7C3, P7C3A20

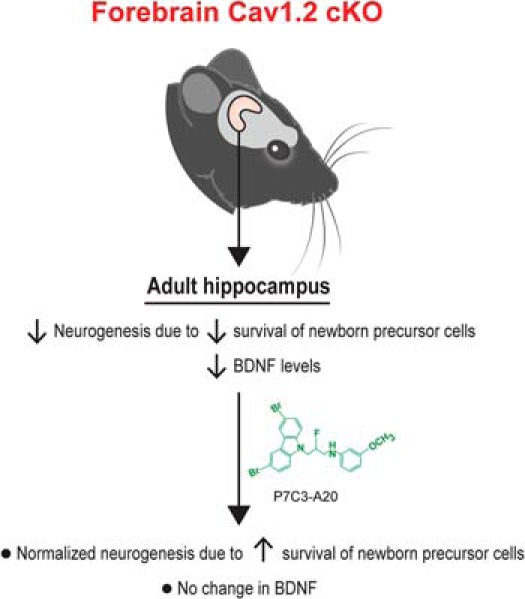

Genetic variations in CACNA1C, which encodes the Cav1.2 subunit of L-type calcium channels (LTCCs), are associated with multiple forms of neuropsychiatric disease that manifest high anxiety in patients.

Abstract

Genetic variations in CACNA1C, which encodes the Cav1.2 subunit of L-type calcium channels (LTCCs), are associated with multiple forms of neuropsychiatric disease that manifest high anxiety in patients. In parallel, mice harboring forebrain-specific conditional knockout of cacna1c (forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO) display unusually high anxiety-like behavior. LTCCs in general, including the Cav1.3 subunit, have been shown to mediate differentiation of neural precursor cells (NPCs). However, it has not previously been determined whether Cav1.2 affects postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo. Here, we show that forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice exhibit enhanced cell death of young hippocampal neurons, with no change in NPC proliferation, hippocampal size, dentate gyrus thickness, or corticosterone levels compared with wild-type littermates. These mice also exhibit deficits in brain levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and Cre recombinase-mediated knockdown of adult hippocampal Cav1.2 recapitulates the deficit in young hippocampal neurons survival. Treatment of forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice with the neuroprotective agent P7C3-A20 restored the net magnitude of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis to wild-type levels without ameliorating their deficit in BDNF expression. The role of Cav1.2 in young hippocampal neurons survival may provide new approaches for understanding and treating neuropsychiatric disease associated with aberrations in CACNA1C.

Visual Abstract

Significance Statement

Aberrant postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis and CACNA1C mutations are associated with neuropsychiatric diseases manifesting high anxiety, and mice deficient in Cav1.2 neuronal expression display high anxiety-like behavior. Here, we report that these mice also display deficient postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis by virtue of elevated death of young hippocampal neurons, along with decreased expression of the endogenous proneurogenic agent brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). We further show that treatment of these mice with the neuroprotective agent P7C3-A20 circumvents the BDNF deficiency to safely and effectively normalize hippocampal neurogenesis without altering BDNF levels. Pharmacologic agents derived from the P7C3 family of neuroprotective compounds could thus provide a new therapeutic approach for treating patients suffering from neuropsychiatric disease associated with aberrations in CACNA1C.

Introduction

CACNA1C is one of the most widely reproduced risk genes for neuropsychiatric disorders (Heyes et al., 2015), including bipolar disorder (Ferreira et al., 2008; Sklar et al., 2008; Green et al., 2010, 2013; Lee et al., 2011; Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group, 2011; Nurnberger et al., 2014; Ament et al., 2015), schizophrenia (Nyegaard et al., 2010; Hamshere et al., 2013; Ripke et al., 2013; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium, 2014) , and major depressive disorder (Casamassima et al., 2010; Green et al., 2010). CACNA1C was also recently identified in the largest human genome-wide association study to date as one of only two genes presenting a common risk factor across five major forms of neuropsychiatric illness: major depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2013). It is not known, however, how CACNA1C exerts such pleiotropic effects on psychopathology.

CACNA1C encodes the voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (LTCC) Cav1.2, which allows cellular influx of calcium following transient changes in membrane potential. This ultimately activates downstream pathways of genetic transcription, such as for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; Ghosh et al., 1994; Tao et al., 1998). Cav1.2 also plays an important role in synaptic plasticity related to neuropsychiatric illness and drug addiction (Giordano et al., 2010; Schierberl et al., 2011), reward-driven behavior (Wessa et al., 2010; Lancaster et al., 2014), fear conditioning (White et al., 2008; Langwieser et al., 2010), and cognition (Moosmang et al., 2005; White et al., 2008). Furthermore, Cav1.2, and not the other brain-specific LTCC subunit Cav1.3, mediates anxiety-like behavior in mice (Dao et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012). Specifically, mice harboring forebrain-specific conditional knockout of cacna1c (forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO) show elevated anxiety-like behavior in the light/dark conflict test, the open-field test, and the elevated plus maze (Lee et al., 2012). Notably, anxiety is a prominent component of all forms of neuropsychiatric illness in which CACNA1C has been implicated.

Deisseroth et al. (2004) have previously shown a bidirectional regulatory role of LTCCs in adult-derived neural precursor cell proliferation in vitro, and Cav1.3 has recently been demonstrated to modulate both proliferation of postnatal neural precursor cells (NPCs) and survival of young hippocampal neurons in the hippocampus, such that elimination of Cav1.3 results in reduced size of the dentate gyrus (Marschallinger et al., 2015). This effect was related to expression of Cav1.3 in both immature NPCs (Nestin-positive) and mature (NeuN-positive) young hippocampal neurons, whereas Cav1.2 expression is restricted to only mature young hippocampal neurons (Marschallinger et al., 2015) in adult mice. However, it has not previously been determined whether Cav1.2 exerts a unique or complementary role in LTCC-mediated hippocampal neurogenesis, the net magnitude of which is a balance of proliferation of NPCs and survival of young hippocampal neurons into which NPCs differentiate. We sought to address this question because of the role of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in the broad spectrum of neuropsychiatric diseases in which aberrations in both CACNA1C (as described above) and postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis have been implicated, including major depression (Serafini et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2015), schizophrenia (Pieper et al., 2005; Pickard et al., 2006; Reif et al., 2007; Le Strat et al., 2009; Pickard 2011; Wu et al., 2013; Schreiber and Newman-Tancredi, 2014), bipolar disorder (Knight et al., 2012; Nurnberger et al., 2014; Takamura et al., 2014), autism (Amiri et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2013; Stanco et al., 2014), and ADHD (Dabe et al., 2013; Jolly et al., 2013; Ohira et al., 2013; Kobayashi et al., 2014). Specifically, we applied forebrain-Cav1.2 conditional deletion (cKO), as well as viral vector-mediated cacna1c gene elimination in adult mice, to quantify hippocampal neurogenesis and other neurophysiologic parameters following spatial and temporal manipulation of Cav1.2 expression.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the University of Iowa, Weill Cornell Medical College, and UT Southwestern animal care committee’s regulations. Animals were housed in temperature-controlled conditions, provided food and water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (7:00 A.M. to 7:00 P.M.). Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Forebrain- Cav1.2 cKO mice were generated by crossing homozygous cacna1c (Cav1.2) floxed mice (cacna1c fl/fl; Moosmang et al., 2005) with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the alpha-CaMKII promoter (CaMKII-Cre). The CaMKII-Cre T29-1 line from Jackson Laboratories was used. In this line, Cre expression is activated at postnatal day (P)18, thereby circumventing early developmental compensatory adaptations. HETs and forebrain- Cav1.2 cKO were indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) in weight, development, and general health.

BrdU staining

After BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) administration, mice were euthanized at the described time points by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde at pH 7.4 and brains were processed for immunohistochemical detection of incorporated BrdU in the hippocampus. Dissected brains were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, and then cryoprotected in sucrose before being sectioned into 40-μm-thick free-floating sections. Unmasking of BrdU antigen was achieved through incubating tissue sections for 2 h in 50% formamide/2× saline-sodium citrate (SSC) at 65°C, followed by a 5 min wash in 2× SSC and subsequent incubation for 30 min in 2 m HCl at 37°C. Sections were processed for immunohistochemical staining with mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU (1:100, Roche). The number of BrdU+ cells in the entire dentate gyrus subgranular zone (SGZ) was quantified by counting BrdU+ cells within the SGZ and dentate gyrus in every fifth section throughout the entire hippocampus, and then normalizing for dentate gyrus volume using Nikon Metamorph and NIH ImageJ software with appropriate conversion factors.

Surgery

Anesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg)/xylazine mixture (10 mg/kg). A midline incision was made, local anesthesia (Marcaine) applied, the head leveled, and holes formed through the skull using a 25 gauge needle. Region-specific deletion of cacna1c was generated by manual bilateral infusion of AAV2/2-Cre-GFP (Vector BioLabs; 0.75 μl/side) into the hippocampus of cacna1cfloxed/floxed mice through a 2.5 μl Hamilton syringe at a rate of 0.1 μl/min. AAV2/2-GFP (Vector BioLabs) was used as a control. The coordinates for the hippocampus were as follows: anterior–posterior −2 mm; media–lateral ±1.6 mm; dorsal–ventral −1.8 mm, at a 10°angle. The needle was held in place for an additional 5 min after infusion to ensure complete delivery of virus. After a minimum of 3 weeks to allow for maximal Cre recombinase expression, mice were administered 50 mg/kg BrdU for 5 d and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) 24 h after the last injection of BrdU.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

Cav1.2 fluorescent immunohistochemistry was performed to confirm elimination of Cav1.2. Fluorescent immunohistochemistry was also used to confirm injection placement. Mice were transcardially perfused with 4% PFA, and brains were dissected and postfixed overnight in 4% PFA followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose at 4°C for at least 72 h. Forty-micrometer-thick sections spanning the hippocampus were obtained using a sliding microtome and incubated in anti-chicken GFP (1:10,000, Aves Labs) and anti-rabbit glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:1000, Invitrogen) primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Sections were rinsed in 0.1 m phosphate-buffer (PB) and incubated with donkey AlexaFluor 488 (1:300) and AlexaFluor 568 (1:300) antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Doublecortin fluorescent immunohistochemistry was performed to analyze cells in the dentate gyrus that had recently committed to neuronal fate. Sections were incubated in anti-guinea pig doublecortin (1:5000, Millipore) primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Sections were rinsed in 0.1 m PB and incubated with donkey AlexaFluor 594 (1:400) antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were imaged using an epifluorescent microscope (Leica DM550B with Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence 3.0.0 build 8134 software, Leica Microsystems).

q-PCR

To measure doublecortin (DCX) mRNA levels in forebrain Cav1.2 cKO mice and AAV2-2/2-Cre-GFP injected cacna1c floxed (cacna1c fl/fl) mice, mice were euthanized by rapid decapitation and whole brains were rapidly dissected. Brain tissue was sectioned on a 1 mm brain block. Dentate gyrus-containing tissue punches were obtained from forebrain Cav1.2 cKO and wild-type mice. For AAV2/2-Cre-GFP and AAV2/2-GFP injected mice, GFP goggles (BLS) were used to visualize GFP signal in brain sections containing the dentate gyrus and to selectively dissect GFP-positive tissue. Tissue punches were processed for total RNA isolation using the mirVana RNA isolation kit (Life Technologies) and cDNA was synthesized from purified RNA using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). Cav1.2 mRNA levels were measured using cacna1c-specific primers (Qiagen QuantiTect Primer assay QT00150752), and DCX levels were measured using DCX-specific primers (Qiagen QuantiTect Primer assay QT02521155) on an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Cycle threshold (Ct) values for target genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene gapdh (QuantiTect Primer assay QT01658692, Qiagen). Each experiment was performed in triplicate and values were averaged.

BDNF ELISA

Mature BDNF protein level was measured using the BDNF Emax ImmunoAssay (ELISA) system (Promega), with recombinant mature BDNF as a standard. Standard and samples were performed in duplicate, with each group containing 10–14 samples. Protein was extracted and quantified following the manufacturer’s protocol. Tissue samples were homogenized in lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mm HEPES, 2 mm NaF) containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors, and then incubated by rotation at 4°C for 1 h. Homogenized tissue was centrifuged at maximum speed and the supernatant containing total protein was collected and quantified using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each sample was diluted 1:1 with block and sample buffer (BSB), and placed in designated wells of a 96-well plate previously coated with BDNF antibody in carbonate buffer (25 mm Na2CO3 and 25 mm Na2HCO3, pH 9.7, incubated at 4°C), followed by blocking with BSB. A second coating of primary anti-human BDNF antibody was added, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The colorimetric reaction was initiated by tetramethylbenzidine. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by addition of 1N HCl, and absorbance was read at 450 nm on a plate reader (iMark Absorbance Microplate Reader, Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Corticosterone levels

To measure baseline and stress-induced corticosterone levels, plasma samples were isolated from 7- to 15-week-old forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO and wild-type mice at 1:00–2:00 P.M. Plasma was isolated from trunk blood. Blood was allowed to sit at room temperature for 60 min and spun at 1200 × g for 15 min. Supernatant was isolated and stored at −20°C. For all restraint stress experiments, mice were restrained for 30 min in decapicones. Plasma corticosterone levels were measured using the high-sensitivity corticosterone enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (AC-15F1, Immunodiagnostic Systems). Samples were analyzed in duplicate. Concentrations were determined per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Morphometric analysis of hippocampal size

Four percent paraformaldehyde-fixed mouse brains were sectioned in the coronal plane, paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 8-μm-thickness, and stained with hematoxylin & eosin. Histological sections were obtained at 50 mm intervals. Measurements of the hippocampus, dentate granular cell layer, and forebrain were taken at the coronal level in which CA1 approaches the midline and the upper blade of the dentate gyrus runs parallel to the surface of the brain. An ocular lens fitted with an etched grid was used to measure the dentate, CA1, and CA3 height and neuronal size (60×), as well as hippocampal dimensions (2×).

P7C3-A20 treatments

All mice were single-housed for the duration of treatment. Forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO and wild-type littermate mice received 10 mg/kg P7C3-A20 or vehicle (5% DMSO, 20% cremaphor in 5% dextrose), intraperitoneally, twice a day for 30 d, starting at P21. This dose of P7C3-A20 was chosen based on efficacy in multiple animal models of neuroprotection (De Jesus-Cortés et al., 2012; Tesla et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2014). Mice were transcardially perfused with 4% PFA 24 h after the last BrdU injection. In separate experiments, brains were flash frozen and processed for BDNF ELISA.

Statistics

For all experiments, data were first analyzed for normality using a Shapiro–Wilk test. If the data were normally distributed, a parametric independent-samples t test or two-way ANOVA test was then applied. For data that were not normally distributed, a nonparametric independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test (as specified in figure legends), was applied. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant and all analyses were performed using SPSS v19 (SPSS). Graphs were constructed in GraphPad Prism v6.0 for Macintosh.

Results

Cav1.2 channels support postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis

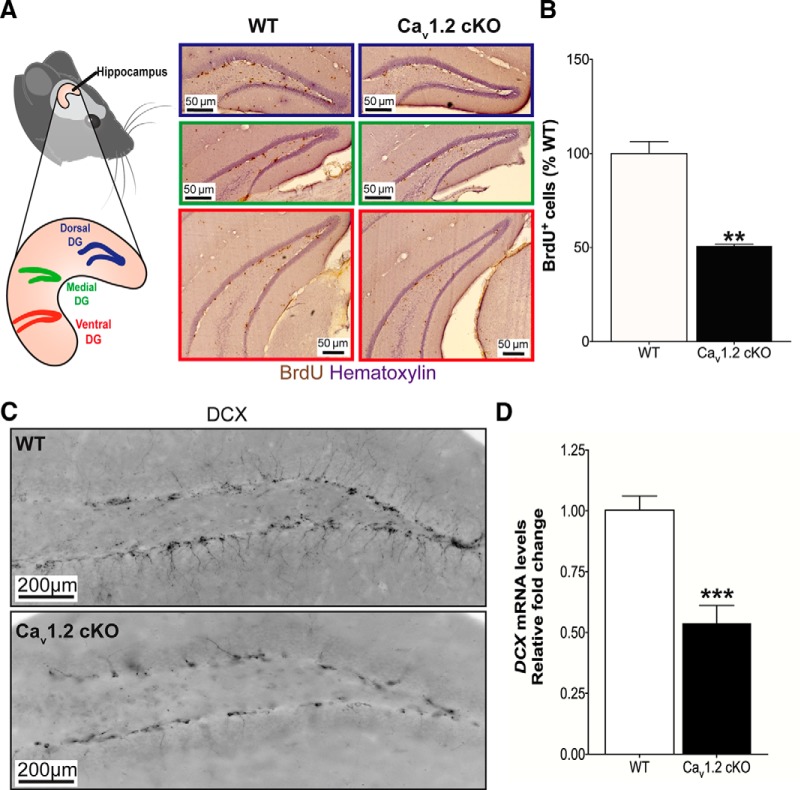

To examine the net magnitude of adult hippocampal neurogenesis, which results from the balance of proliferation of NPCs and survival of young adult hippocampal neurons into which NPCs differentiate, in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice, all mice received intraperitoneal injections of the thymidine analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, 50 mg/kg/d) once daily for 5 d. Mice were then euthanized for immunohistochemical analysis of the brain 24 h after the final BrdU injection. Compared to wild-type littermates, forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice showed ∼50% fewer BrdU+ cells throughout the hippocampus (Fig. 1A,B; F(1,7) = 57.714, p = 0.004). These mutant mice also exhibited significantly lower expression of doublecortin (Fig. 1C,D; F(1,11) = 24.928, p < 0.001), a microtubule-associated protein that serves as a marker of neurogenesis by virtue of transient expression in newly formed neurons between their birth and final maturation (Brown et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Cav1.2 supports adult hippocampal neurogenesis. A, Left, Graphical representation of the dorsal, medial, and ventral dentate gyrus (DG) in which BrdU+ staining was quantified. Right, Representative images of BrdU- and hematoxylin-stained DG from forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO and WT littermate mice. B, Forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice show significantly lower BrdU+ cells in the DG compared with WT animals (B; WT, n= 4; KO, n=4; **p = 0.004, independent samples t test). C, D, Forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice also show lower DCX protein (C; WT, n=3; KO, n=3) and mRNA levels (D; WT, n=6; KO, n=6; ***p < 0.001, independent samples t test) compared with WT animals. All graphs are represented as mean ± SEM.

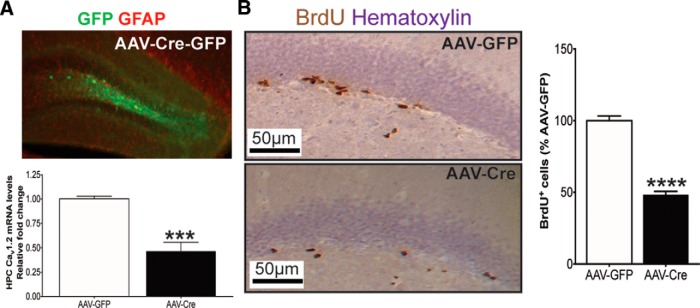

To directly evaluate the effect of spatially- and temporally-specific elimination of Cav1.2 in the adult hippocampus, and thus differentiate between an adult versus developmental effect of Cav1.2 on postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis, we next stereotaxically delivered AAV2/2-Cre-GFP into the dentate gyrus of adult cacna1c fl/fl mice. This resulted in significantly lower levels of Cav1.2 mRNA compared to control AAV2/2-GFP injected mice (Fig. 2A; F(1,9) = 31.536, p < 0.001). As with forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice, focal knockout of Cav1.2 in the adult dentate gyrus resulted in an ∼50% reduction in BrdU+ cells, compared with control mice injected with AAV2/2-GFP (Fig. 2B; F(1,14) = 165.989, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Selective elimination of Cav1.2 in adult dentate gyrus results in lower neurogenesis. A, Top, Representative image of GFP-labeled cells within the dentate gyrus of Cav1.2fl/fl mice injected with AAV2/2-Cre-GFP. Bottom, AAV2/2-Cre-GFP significantly decreased Cav1.2 mRNA compared with control AAV2/2-GFP injected mice (A; AAV2/2-GFP, n=5; AAV2/2-Cre, n= 5; ***p < 0.001, independent samples t test). B, Adult focal hippocampal knockout of Cav1.2 results in significantly lower BrdU+ cells in the dentate gyrus (AAV2/2-GFP, n=6; AAV2/2-Cre, n= 9; ****p < 0.0001, independent samples t test). All graphs are represented as mean ± SEM.

Cav1.2 channels are necessary for survival of young hippocampal neurons, and not for proliferation of neural precursor cells

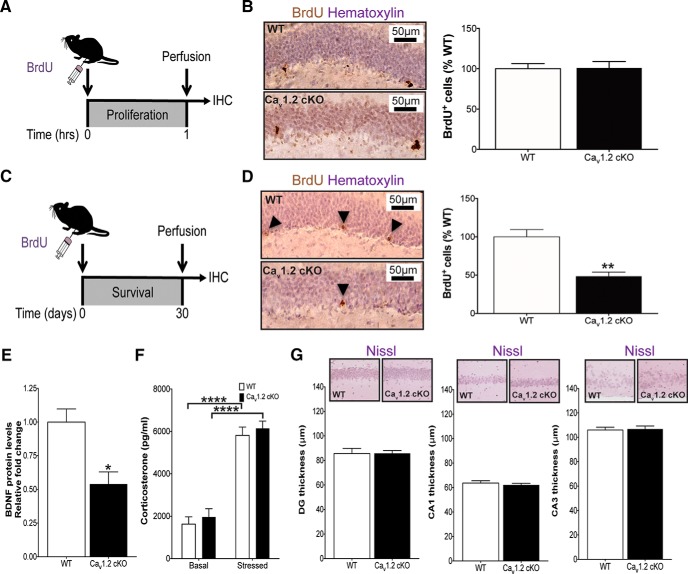

The net magnitude of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis is a balance of proliferation of NPCs and survival of the young hippocampal neurons into which NPCs differentiate, and indeed ∼40% of young hippocampal neurons normally die within the first week of their birth (Pieper et al., 2010). Recently, Cav1.3 has been shown to be essential for both of these processes (Marschallinger et al., 2015). Therefore, we investigated whether Cav1.2 was necessary for proliferation of NPCs, survival of young hippocampal neurons, or both. To address this question, adult forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice were injected with a single bolus of BrdU (150 mg/kg, i.p.), followed by transcardial perfusion either 1 h later (to measure proliferation of NPCs; Fig. 3A) or 30 d later (to measure survival of young hippocampal neurons; Fig. 3C), per established methods (Pieper et al., 2010). We observed no difference in the number of BrdU+ cells at the 1 h time point between forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice and wild-type littermates (Fig. 3B; F(1,6) = 0.039, p = 0.935), indicating that in contrast to Cav1.3, Cav1.2 does not affect NPC proliferation. However, forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice exhibited an ∼50% lower number of BrdU+ cells relative to wild-type littermates 30 d after BrdU injection (Fig. 3D; F(1,11) = 18.082, p = 0.002), demonstrating that Cav1.2 is necessary for survival of young hippocampal neurons.

Figure 3.

Cav1.2 controls survival of young hippocampal neurons, associated with lower BDNF levels in the absence of differences in corticosterone levels or hippocampus volume. A, C, Graphical representation of BrdU pulse chase experiments to determine proliferation (A) versus survival (C). IHC, Immunohistochemistry. B, D, Forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice display normal proliferation as compared with WT animals, with no difference in BrdU+ cells 1 h after BrdU administration (B; WT, n=4; KO=3; p = 0.935, independent samples t test). Forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice do, however, show a deficit in survival of young hippocampal neurons, as indicated by significantly lower BrdU+ cells in the dentate gyrus 30 d after BrdU injection (D; WT n=7; KO, n=5; **p = 0.002, independent samples t test). Arrows point to BrdU-positive cells. E, BDNF protein levels are significantly lower in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice compared with WT animals (WT, n=6; KO, n=10; *p = 0.005, independent samples t test). F, Corticosterone levels are not different between forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice and WT animals (Basal: WT, n=14; KO, n=15; Stressed: WT, n=15; KO, n=7; main effect of basal versus stressed ****p < 0.0001; main effect of genotype p = 0.4232, two-way ANOVA). G, Nissl staining showed no differences between forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO and WT thickness of the dentate gyrus (DG; p = 0.986, independent samples t test), CA1 (p = 0.518, independent samples t test) and CA3 (p = 0.898, independent samples Mann–Whitney U test) layers of the hippocampus (WT, n= 5; KO, n= 9). All graphs are represented as mean ± SEM.

Forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice display deficient levels of hippocampal BDNF, with normal glucocorticoid levels and hippocampal size

Because BDNF has been shown to support postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis (Duman and Monteggia, 2006; Chen et al., 2015), and brain levels of BDNF are regulated by L-type calcium channels (Ghosh et al., 1994; Tao et al., 1998), we wondered whether hippocampal levels of BDNF might be altered in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice. Via ELISA, we found that forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice have significantly lower hippocampal BDNF protein levels compared with WT littermates (Fig. 3E; F(1,15) = 11.105, p = 0.005).

Next, because glucocorticoid receptors have been shown to modulate connectivity and integration of young hippocampal neurons (Fitzsimons et al., 2013), and forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice display markedly high levels of anxiety-like behavior that is often associated with elevated levels of stress hormones in animal models, we wondered whether corticosterone levels might also be altered in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice. Enzyme immunoassay revealed differences in corticosterone levels between basal and stressed groups of each genotype (Fig. 3F; F(1,47) = 104.1; p < 0.001). However, there were no genotype-specific differences in either basal- or stressed-condition corticosterone levels between forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO and WT littermate mice (Fig. 3F; F(1,47) = 0.6526; p = 0.423), demonstrating that lower adult neurogenesis in forebrain Cav1.2 cKO mice is not because of altered corticosterone levels.

Finally, because other mouse models with severe deficits in postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis have been shown to harbor abnormal hippocampal morphology (Pieper et al., 2005), we compared hippocampal morphology in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice with WT littermates. Notably, forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice displayed normal overall hippocampal size, as well as normal thickness of the dentate gyrus (F(1,13) = 0.022, p = 0.986), CA1 (F(1,13) = 0.443, p = 0.518), and CA3 (F(1,13) = 0.056, p = 0.898) subregions (Fig. 3G).

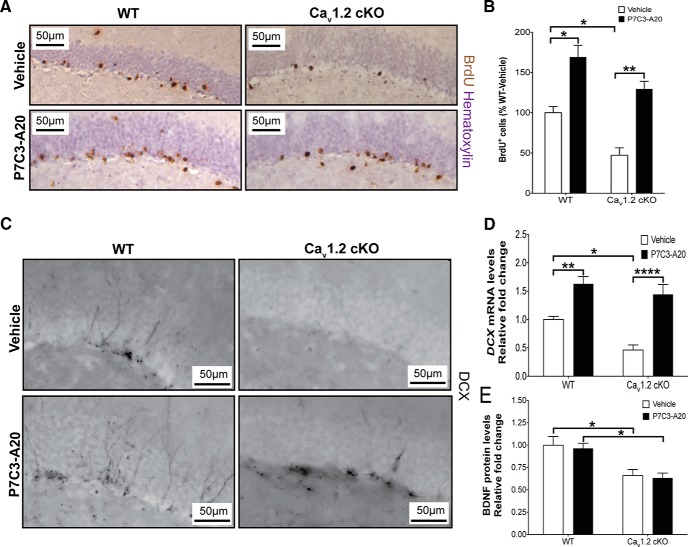

P7C3-A20 rescues survival of young hippocampal neurons in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice without affecting BDNF levels

Recently, the novel aminopropyl carbazole P7C3-class of compounds has been discovered and characterized in in vivo models of neuron cell death, including protection of young hippocampal neurons that thereby increases the net magnitude of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis (Pieper et al., 2010, 2014; Macmillan et al., 2011). Active members of this chemical series have been shown to enhance flux of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) salvage pathway in normal mammalian cells, and facilitate NAD rebound following doxorubicin exposure (Wang et al., 2014). To date, these compounds have shown neuronal protective efficacy in multiple preclinical models of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease (De Jesus-Cortés et al., 2012, 2015; Naidoo et al., 2014), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Tesla et al., 2012), stress-associated depressive-like behavior (Walker et al., 2015), aging-associated cognitive decline (Pieper et al., 2010), peripheral nerve crush injury (Kemp et al., 2015), and traumatic brain injury (Blaya et al., 2014; Dutca et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2014). We therefore wondered whether treatment of forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice with P7C3-A20, one of the most highly active agents in the P7C3 series, might restore to normal the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis. Indeed, 1 month treatment with P7C3-A20 starting at weaning age fully restored neurogenesis in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice to WT levels, as determined by BrdU-labeling (Fig. 4A,B; two-way ANOVA, treatment, F(1,8) = 18.99, p < 0.001; genotype, F(1,8) = 50.97, p = 0.002) and levels of doublecortin (Fig. 4C,D; two-way ANOVA; treatment: F(1,28) = 41.84, p < 0.001; genotype: F(1,28) = 8.568; p = 0.007). Notably, treatment with P7C3-A20 had no effect on hippocampal BDNF levels (Fig. 4E; two-way ANOVA; treatment: F(1,23) = 0.1567, p = 0.696; genotype: F(1,23) = 18.45, p < 0.001). Thus, despite the profound deficit in hippocampal BDNF levels in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice, deficient neurogenesis in this model can still be corrected by BDNF-independent mechanisms.

Figure 4.

Treatment with P7C3-A20 restores hippocampal neurogenesis in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice without affecting BDNF levels. A–C, Treatment with the neuroprotective compound P7C3-A20 significantly increased the levels of BrdU+ cells in the dentate gyrus (A, B; Veh vs P7C3-A20; ****p < 0.0001; WT-Veh, n=3; KO-Veh, n=3; WT-A20, n=3; KO-A20, n=3), DCX protein levels using immunohistochemistry (C), and mRNA levels (D; Veh: WT vs KO; *p = 0.029; WT: Veh vs P7C3-A20, **p = 0.005; KO: Veh vs P7C3-A20; ****p < 0.0001; WT-Veh, n=8; KO-Veh, n=7; WT-A20, n=9; KO-A20, n=8) of both WT and forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO adult animals compared to vehicle-treated groups. E, P7C3-A20 had no effect on BDNF protein levels in either group (WT: Veh vs P7C3-A20, p = 0.9996; KO: Veh vs P7C3-A20, p > 0.999; WT-VEH, n=8; KO-VEH, n=5; WT-A20, n=8; KO-A20, n=6). All graphs are represented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate a previously unidentified role of Cav1.2 in regulating survival of young hippocampal neurons in living mice by studying both forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice and viral vector-mediated specific hippocampal elimination of Cav1.2 within young hippocampal neurons in adult WT mice. Our in vivo data is consistent with a previous in vitro study identifying a role of LTCCs in activity-dependent regulation of adult-derived NPCs in vitro (Deisseroth et al., 2004), as well as another recent in vitro study demonstrating involvement of LTCCs in survival and maturation of newly generated neurons using a clonal line of NPCs established from adult rat hippocampus (Teh et al., 2014). Given the role of hippocampal neurogenesis in multiple forms of neuropsychiatric disease, our findings provide new insight into the potential role of Cav1.2 in the multiple forms of mental illness in which it has been implicated.

We have observed that in the absence of Cav1.2, young hippocampal neurons die at an accelerated rate of ∼50%. Moreover, even though forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice display abnormally high anxiety-like behavior (Lee et al., 2012a), and high corticosterone levels associated with stress are known to reduce hippocampal neurogenesis (Cameron and Gould, 1994; Yu et al., 2010), these mice show normal levels of baseline and stressed brain corticosterone, indicating that their deficit in neurogenesis is not due to secondary effects of abnormally high anxiety.

The observed effect of elimination of Cav1.2 on survival of young hippocampal neurons is in contrast to what was recently described for genetic elimination of Cav1.3, which exerts a more profound effect on hippocampal neurogenesis by regulating both proliferation of NPCs and survival of young hippocampal neurons, resulting in reduced hippocampal size (Marschallinger et al., 2015). Presumably, the differential roles of these two major forms of LTCCs in the brain are related to the fact that within the hippocampal neurogenic niche Cav1.2 is expressed exclusively in mature (NeuN-positive cells) young hippocampal neurons, whereas Cav1.3 is expressed in both newly formed immature NPCs (nestin-positive cells) and mature young hippocampal neurons (Marschallinger et al., 2015). An interesting question that will be addressed in future studies is whether this is a cell autonomous or non-autonomous effect. The latter is certainly likely, given that Cav1.2 mediates BDNF production, which can be released from cells to act on both secreting and neighboring neurons. The fact that genetic deletion of Cav1.3 also results in diminished hippocampal size (Marschallinger et al., 2015) suggests that Cav1.3 could play a role in both developmental and postnatal neurogenesis. Here, we show that genetic deletion of Cav1.2, by contrast, has no effect on hippocampal size, suggesting that Cav1.2 plays a specific role in regulating survival of young hippocampal neurons in the mature brain rather than during development. Indeed, we have demonstrated an essential role of Cav1.2 in postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis by viral vector-mediated elimination in adult mice. Apparently, under nonpathologic conditions in the adult animals tested, this decreased survival of young hippocampal neurons is not sufficient to reduce hippocampal size. Future experiments in animals under circumstances of increased cellular stress, such as occurs with injury or aging, will help determine whether decreased survival of young hippocampal neurons in this model compromises overall morphology of the dentate gyrus under stressed conditions. Together, these results suggest that dynamic modulation of Cav1.2-mediated signaling in the adult brain might help ameliorate related disease symptoms.

LTCC signaling has been linked to BDNF production in hippocampal neurons (Ghosh et al., 1994), and we report here for the first time that the brains of forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice are deficient in hippocampal levels of BDNF. LTCCs serves as a primary Ca2+ source of BDNF synthesis via transcriptional regulation of the promoter for Bdnf exon IV, which represents the most highly-expressed bdnf splice variant (West et al., 2014). Multiple LTCC-activated transcriptional regulators, including CREB, Ca2+ response factor (CaRF), and MeCP2, control bdnf expression by binding to the promoter of bdnf exon IV (Tao et al 1998, 2002,2009; Chen et al., 2003; Chao and Zoghbi, 2009), and we propose that the lack of activation of these factors in the hippocampus results in lower BDNF in the forebrain of Cav1.2 KO mice. BDNF is known to support neurogenesis, but has not proven to be an effective therapeutic agent to date. We show here that extended treatment of forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice with the neuroprotective aminopropyl carbazole P7C3-A20 restored hippocampal neurogenesis to normal levels by ameliorating the aberrantly high rate of death of young hippocampal neurons in these mice. This therapeutic effect was achieved without affecting hippocampal BDNF levels, suggesting that P7C3 compounds offer an alternative therapeutic route to restore neurogenesis in a manner that circumvents deficient BDNF signaling through an independent mechanism.

The net magnitude of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis is a balance of proliferation of NPCs and survival of the ensuing young hippocampal neurons. Future experiments will address the impact of restoring the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis to normal levels in forebrain-Cav1.2 cKO mice, as hippocampal neurogenesis has been linked to anxiety and depression-like behavior, as well as learning and memory. Such behavioral studies will provide important clarification of the relationship between the observed neural changes and risk for pathology-associated behaviors in this model. Finally, our identification of a new role for Cav1.2 in neuronal cell survival may provide new insight and approaches to treating neuropsychiatric disease. Future experiments will examine whether Cav1.2 also serves a selective role in mediating mature neuronal cell death as well. In conclusion, the results of our work may provide new treatment opportunities for patients suffering from neurodegenerative disease, including forms of mental illness associated with neuronal cell death.

Synthesis

The decision was a result of the Reviewing Editor Lorna Role and the peer reviewers coming together and discussing their recommendations until a consensus was reached. A fact-based synthesis statement explaining their decision and outlining what is needed to prepare a revision is listed below. The following reviewers agreed to reveal their identity: Kevin Bath, Shaoyu Ge

The authors provide findings supporting the idea that conditional deletion of the Cav1.2 channel in mice decreases the survival of post-natal generated hippocampal dentate gyrus granule neurons and results in diminished BDNF expression. The experiments are well done, and the results shed light on our understanding of how postnatally-born neurons develop and integrate into the pre-existing circuits. The authors go further to demonstrate that levels of survival of young, post-natal neurons can be rescued by the neuroprotective agent P7C3-A20, in a BDNF autonomous fashion. The observation of the effects on neuronal survival are compelling and the manuscript is well written. The authors suggest that such disruptions may contribute to the broad array of pathological conditions associated with mutations in the cacna1c gene.

Major Points:

1. The major reservation of the reviewers was with the interpretation of the data in hand. The manuscript (title through discussion) needs to be carefully rewritten to confine the conclusions to pertaining to the survival of young hippocampal neurons. (i.e. not to neural precursor cells)

Specifically, the reviewers argue that with the current experimental conditions are not appropriate for testing effects of CaV1.2 depletion on proliferation or on neural progenitors. The reason for this more reserved set of conclusions is that the study used the CaV1.2 floxed line crossed with the CaMKII cre. As the authors state -CaMKII starts to be active at specific stages in young neurons. It is generally off in progenitors. As such, the conditional depletion of CaV1.2 in CAMKII neurons is relatively restricted to young neurons in the postnatal brain and as such not apropos for assessment of effects on proliferation

The reviewers agree that the authors can and do answer important questions about the survival of young neurons with the experimental paradigm used.

2. The other major issue raised by the reviewers is that the impact of this paper would be significantly enhanced if the authors had carried out behavioral studies to test if P7C3-A20 were sufficient to also rescue behavioral effects of loss of cacna1c on any pathological outcome (for example anxiety). Such studies would bolster the potential clinical-translational significance of the current findings to show that augmentation of survival of young neurons is, or is not, sufficient to rescue behavioral symptoms of disorders associated with mutations in this gene.

If such behavioral data is available or could be added to the manuscript this would substantially increase the impact of the paper. In lieu of this, it is requested that the authors indicate that such behavioral studies would provide important clarification of the relationship between the observed neural changes and risk for pathology-associated behaviors in the animals.

Additional Issues

1)Re figure 1 and associated methods.

The methods pertinent to Figure 1 need clarification. The authors state the procedure for the Q-PCR used GFP as a marker, but figure 1 presents data from Cav1.2/CamKII-cre mice without GFP. The methods for obtaining the data in Fig 1D should be clarified.

It is surprising that the authors did not observe any changes in the granule cell layer given the strong effects on survival (Fig. 1C&D). It would be helpful for the authors to briefly discuss this apparent discrepancy.

Minor: add scale for figure 1a.

2)Re figure 2.

Please specify which AAV serotype was used to deliver Cre (it appears that most mossy cells and some hilar interneurons got infected?).

The authors unnderscore the cell autonomous effect: to support this conclusion they should confirm that some GFP+ (AAV-Cre-gfp) cells are also DCX positive.

It would be best if the possibility for non-cell autonomous effect is at least presented in the discussion.

Do the authors have data addressing the data in Figure 2 using the AAV CaMKII-Cre - this would better parallel figure 1 studies)

3)Re figure 3.

The presentation of this figure and the text should be revised to reflect the limitations as per major point #1 (above). Since the CaV1.2 gene expression would be expected to be largely intact in the progenitors one would not predict changes in this population (Figure 3a).

The authors should briefly discuss 'why' the BDNF decreases in the CaV1.2-CaMKII off mice.

4)Re Figure 4.

It should be discussed that P7C3-A20 and the CaV1.2 effects could be independent.

** additional note ** One of the authors holds patents on the P7C3 class of neuroprotective chemicals.

References

- Ament SA, Szelinger S, Glusman G, Ashworth J, Hou L, Akula N, Shekhtman T, Badner JA, Brunkow ME, Mauldin DE, Stittrich AB, Rouleau K, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Nurnberger JI Jr, Edenberg HJ, Gershon ES, Schork N; Bipolar Genome Study. (2015) Rare variants in neuronal excitability genes influence risk for bipolar disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 3576-3581. 10.1073/pnas.1424958112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri A, Cho W, Zhou J, Birnbaum SG, Sinton CM, McKay RM, Parada LF (2012) Pten deletion in adult hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells causes cellular abnormalities and alters neurogenesis. J Neurosci 32:5880-5890. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5462-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaya MO, Bramlett HM, Naidoo J, Pieper AA, Dietrich WD (2014) Neuroprotective efficacy of a proneurogenic compound after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 31:476-486. 10.1089/neu.2013.3135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JP, Couillard-Després S, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG (2003) Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol 467:1-10. 10.1002/cne.10874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Gould E (1994) Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience 61: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamassima F, Huang J, Fava M, Sachs GS, Smoller JW, Cassano GB, Lattanzi L, Fagerness J, Stange JP, Perlis RH (2010) Phenotypic effects of a bipolar liability gene among individuals with major depressive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 153B: 303-309. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Zoghbi HY (2009) The yin and yang of MeCP2 phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 4577-4578. 10.1073/pnas.0901518106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WG, Chang Q, Lin Y, Meissner A, West AE, Griffith EC, Jaenisch R, Greenberg ME (2003) Derepression of BDNF transcription involves calcium-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2. Science 302:885-889. 10.1126/science.1086446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2013) Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet 381: 1371-1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabe EC, Majdak P, Bhattacharya TK, Miller DS, Rhodes JS (2013) Chronic d-amphetamine administered from childhood to adulthood dose-dependently increases the survival of new neurons in the hippocampus of male C57BL/6J mice. Neuroscience 231:125-135. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao DT, Mahon PB, Cai X, Kovacsics CE, Blackwell RA, Arad M, Shi J, Zandi PP, O’Donell P; Bipolar Genome Study (BiGS) Consortium, Knowles JA, Weissman MM, Coryell W, Scheftner WA, Lawson WB, Levinson DF, Thompson SM, Potash JB, Gould TD (2010) Mood disorder susceptibility gene CACNA1C modifies mood-related behaviors in mice and interacts with sex to influence behavior in mice and diagnosis in humans. Biol Psych 68:801–810. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus-Cortés H, Xu P, Drawbridge J, Estill SJ, Huntington P, Tran S, Britt J, Tesla R, Morlock L, Naidoo J, Melito LM, Wang G, Williams NS, Ready JM, McKnight SL, Pieper AA (2012) Neuroprotective efficacy of aminopropyl carbazoles in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:17010-17015. 10.1073/pnas.1213956109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus-Cortés H, Miller AD, Britt JK, DeMarco AJ, De Jesus-Cortes M, Steubing E, Naidoo J, Wasquez-Rosa W, Morlock L, Williams NS, Ready JM, Narayanan NS, Pieper AA (2015) Protective efficacy of P7C3-S243 in the 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis 1:15010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Singla S, Toda H, Monje M, Palmer TD, Malenka RC (2004) Excitation-neurogenesis coupling in adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neuron 42:535-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM (2006) A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 59:1116-1127. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutca LM, Stasheff SF, Hedberg-Buenz A, Rudd DS, Batra N, Blodi FR, Yorek MS, Yin T, Shankar M, Herlein JA, Naidoo J, Morlock L, Williams N, Kardon RH, Anderson MG, Pieper AA, Harper MM (2014) Early detection of subclinical visual damage after blast-mediated TBI enables prevention of chronic visual deficit by treatment with P7C3-S243. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:8330-41. 10.1167/iovs.14-15468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MA, O'Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L, Fan J, Kirov G, Perlis RH, Green EK, Smoller JW, Grozeva D, Stone J, Nikolov I, Chambert K, Hamshere ML, Nimgaonkar VL, Moskvina V, Thase ME, Caesar S. (2008) Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat Genet 40: 1056-1058. 10.1038/ng.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons CP, van Hooijdonk LW, Schouten M, Zalachoras I, Brinks V, Zheng T, Schouten TG, Saaltink DJ, Dijkmans T, Steindler DA, Verhaagen J, Verbeek FJ, Lucassen PJ, de Kloet ER, Meijer OC, Karst H, Joels M, Oitzl MS, Vreugdenhil E (2013) Knockdown of the glucocorticoid receptor alters functional integration of newborn neurons in the adult hippocampus and impairs fear-motivated behavior. Mol Psychiatry 18:993-1005. 10.1038/mp.2012.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Carnahan J, Greenberg ME (1994) Requirement for BDNF in activity-dependent survival of cortical neurons. Science 263:1618-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP, Tropea TF, Satpute SS, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Striessnig J, Kosofsky BE, Rajadhyaksha AM (2010) Molecular switch from L-type Cav1.3 to Cav1.2 Ca2+ channel signaling underlies long-term psychostimulant-induced behavioral and molecular plasticity. J Neurosci 30:17051-17062. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2255-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EK, Grozeva D, Jones I, Jones L, Kirov G, Caesar S, Gordon-Smith K, Fraser C, Forty L, Russell E, Hamshere ML, Moskvina V, Nikolov I, Farmer A, McGuffin P; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Holmans PA, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC, Craddock N (2010) The bipolar disorder risk allele at CACNA1C also confers risk of recurrent major depression and of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 15: 1016-1022. 10.1038/mp.2009.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EK,Hamshere M, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K, Fraser C, Russell E, Grozeva D, Kirov G, Holmans P, Moran JL, Purcell S, Sklar P, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Jones L, Jones IR, Craddock N (2013) Replication of bipolar disorder susceptibility alleles and identification of two novel genome-wide significant associations in a new bipolar disorder case-control sample. Mol Psychiatry 18:1302-1307. 10.1038/mp.2012.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamshere ML, Walters JT, Smith R, Richards AL, Green E, Grozeva D, Jones I, Forty L, Jones L, Gordon-Smith K, Riley B, O’Neill FA, Kendler KS, Sklar P, Purcel S, Kranz J; Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-wide Association Study Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium+; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Morris D, Gill M, Holmans P, Craddock N, Corvin A, Owen MJ (2013) Genome-wide significant associations in schizophrenia to ITIH3/4, CACNA1C and SDCCAG8, and extensive replication of associations reported by the Schizophrenia PGC. Mol Psychiatry 18:708-712. 10.1038/mp.2012.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes S, Pratt WS, Rees E, Dahimene S, Ferron L, Owen MJ, Dolphin AC (2015) Genetic disruption of voltage-gated calcium channels in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Prog Neurobiol 134:36-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly LA, Homan CC, Jacob R, Barry S, Gecz J (2013) The UPF3B gene, implicated in intellectual disability, autism and ADHD and childhood onset schizophrenia regulates neural progenitor cell behaviour and neuronal outgrowth. Hum Mol Genet 22: 4673-87. 10.1093/hmg/ddt315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp SW, Szynkaruk M, Stanoulis KN, Wood MD, Liu EH, Willand MP, Morlock L, Naidoo J, Williams NS, Ready JM, Mangano TJ, Beggs S, Salter MW, Gordon T, Pieper AA, Borschel GH (2015) Pharmacologic rescue of motor and sensory function by the neuroprotective compound P7C3 following neonatal nerve injury. Neuroscience 284:202-216. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight HM, Walker R, James R, Porteous DJ, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH, Pickard BS (2012) GRIK4/KA1 protein expression in human brain and correlation with bipolar disorder risk variant status. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 159B:21-29. 10.1002/ajmg.b.31248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Nakatani T, Koda T, Matsumoto K, Ozaki R, Mochida N, Takao K, Miyakawa T, Matsuoka I (2014) Absence of BRINP1 in mice causes increase of hippocampal neurogenesis and behavioral alterations relevant to human psychiatric disorders. Mol Brain 7:12. 10.1186/1756-6606-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster TM, Heerey EA, Mantripragada K, Linden DE (2014) CACNA1C risk variant affects reward responsiveness in healthy individuals. Transl Psychiatry 4:e461. 10.1038/tp.2014.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langwieser N, Christel CH, Kleppisch T, Hofmann F, Wotjak CT, Moosmang S (2010) Homeostatic switch in hebbian plasticity and fear learning after sustained loss of Cav1.2 calcium channels. J Neurosci 30:8367-8375. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4164-08.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MT, Chen CH, Lee CS, Chen CC, Chong MY, Ouyang WC, Chiu NY, Chuo LJ, Chen CY, Tan HK, Lane HY, Chang TJ, Lin CH, Jou SH, Hou YM, Feng J, Lai TJ, Tung CL, Chen TJ, Chang CJ. (2011) Genome-wide association study of bipolar I disorder in the Han Chinese population. Mol Psychiatry 16: 548-556. 10.1038/mp.2010.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS, Ra S, Rajadhyaksha AM, Britt JK, De Jesus-Cortes H, Gonzales KL, Lee A, Moosmang S, Hofman F, Pieper AA, Rajadhyaksha AM (2012) Forebrain elimination of cacna1c mediates anxiety-like behavior in mice. Mol Psych 17:1054-1055. 10.1038/mp.2012.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Strat Y, Ramoz N, Gorwood P (2009) The role of genes involved in neuroplasticity and neurogenesis in the observation of a gene-environment interaction (GxE) in schizophrenia. Curr Mol Med 9:506-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan KS, Naidoo J, Liang J, Melito L, Williams NS, Morlock L, Huntington PJ, Estill SJ, Longgood J, Becker GL, McKnight SL, Pieper AA, De Brabander JK, Ready JM (2011) Development of proneurogenic, neuroprotective small molecules. J Am Chem Soc 133:1428-1437. 10.1021/ja108211m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschallinger J, Sah A, Schmuckermair C, Unger M, Rotheneichner P, Kharitonova M, Waclawiczek A, Gerner P, Jaksch-Bogensperger H, Berger S, Striessnig J, Singewald N, Couillard-Despres S, Aigner L (2015) The L-type calcium channel Cav1.3 is required for proper hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive functions. Cell Calcium 58: 606-616. 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Haider N, Klugbauer N, Adelsberger H, Langwieser N, Müller J, Stiess M, Marais E, Schulla V, Lacinova L, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Storm DR, Hofmann F, Kleppisch T (2005) Role of hippocampal Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in NMDA receptor-independent synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. J Neurosci 25:9883-9892. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1531-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo J, De Jesus-Cortes H, Huntington P, Estill S, Morlock LK, Starwalt R, Mangano TJ, Williams NS, Pieper AA, Ready JM (2014) Discovery of a neuroprotective chemical, (S)-N-(3-(3,6-dibromo-9H-carbazol-9-yl)-2-fluoropropyl)-6-methoxypyridin-2-amine[(-)-P7C3-S243], with improved druglike properties. J Med Chem 57:3746-54. 10.1021/jm401919s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI Jr, Koller DL, Jung J, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Guella I, Vawter MP, Kelsoe JR (2014) Identification of pathways for bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 657-664. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyegaard M, Demontis D, Foldager L, Hedemand A, Flint TJ, Sørensen KM, Andersen PS, Nordentoft M, Werge T, Pedersen CB, Hougaard DM, Mortensen PB, Mors O, Børglum AD (2010) CACNA1C (rs1006737) is associated with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 15: 119-121. 10.1038/mp.2009.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira K, Kobayashi K, Toyama K, Nakamura HK, Shoji H, Takao K, Takeuchi R, Yamaguchi S, Kataoka M, Otsuka S, Takahashi M, Miyakawa T (2013) Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 mutation induces immaturity of the dentate granule cells of adult mice. Mol Brain 6:12. 10.1186/1756-6606-6-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard BS, Pieper AA, Porteous DJ, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ (2006) The NPAS3 gene: emerging evidence for a role in psychiatric illness. Ann Med 38:439-448. 10.1080/07853890600946500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard B (2011) Progress in defining the biological causes of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Mol Med 13:e25. 10.1017/S1462399411001955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper AA, Wu X, Han TW, Estill SJ, Dang Q, Wu LC, Reece-Fincanon S, Dudley CA, Richardson JA, Brat DJ, McKnight SL (2005)The neuronal PAS domain protein 3 transcription factor controls FGF-mediated adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:14052-14057. 10.1073/pnas.0506713102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper AA, Xie S, Capota E, Estill SJ, Zhong J, Long JM, Becker GL, Huntington P, Goldman SE, Shen CH, Capota M, Britt JK, Kotti T, Ure K, Brat DJ, Williams NS, MacMillan KS, Naidoo J, Melito L, Hsieh J. (2010) Discovery of a proneurogenic, neuroprotective chemical. Cell 142:39-51. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper AA, McKnight SL, Ready JM (2014) P7C3 and an unbiased approach to drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Soc Rev 43:6716-26. 10.1039/c3cs60448a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group (2011) Large scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet 43:977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif A, Schmitt A, Fritzen S, Lesch KP (2007) Neurogenesis and schizophrenia: dividing neurons in a divided mind? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 257:290-299. 10.1007/s00406-007-0733-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kähler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Fromer M, Kim Y, Lee SH, Magnusson PK, Sanchez N, Stahl EA, Williams S, Wray NR, Xia K, Bettella F, Borglum AD.; Multicenter Genetic Studies of Schizophrenia Consortium; Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (2013) Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet 45:1150–1159. 10.1038/ng.2742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierberl K, Hao J, Tropea TF, Ra S, Giordano TP, Xu Q, Garraway SM, Hofmann F, Moosmang S, Striessnig J, Inturrisi CE, Rajadhyaksha AM (2011) Cav1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels mediate cocaine-induced GluA1 trafficking in the nucleus accumbens, a long-term adaptation dependent on ventral tegmental area Ca(v)1.3 channels. J Neurosci 31:13562-13575. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2315-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2014) Biological insights from the 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511:421-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R, Newman-Tancredi A (2014) Improving cognition in schizophrenia with antipsychotics that elicit neurogenesis through 5-HT(1A) receptor activation. Neurobiol Learn Mem 110:72-80. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G, Hayley S, Pompili M, Dwivedi Y, Brahmachari G, Girardi P, Amore M (2014) Hippocampal neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors and depression: possible therapeutic targets? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 13:1708-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh C, Bortolato M, Bali N, Godar SC, Scott AL, Chen K, Thompson RF, Shih JC (2013) Cognitive abnormalities and hippocampal alterations in monoamine oxidase A and B knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:12816-12821. 10.1073/pnas.1308037110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, Nimgaonkar VL, McQueen MB, Faraone SV, Kirby A, de Bakker PI, Ogdie MN, Thase ME, Sachs GS, Todd-Brown K, Gabriel SB, Sougnez C, Gates C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M. (2008) Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 13:558–569. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanco A, Pla R, Vogt D, Chen Y, Mandal S, Walker J, Hunt RF, Lindtner S, Erdman CA, Pieper AA, Hamilton SP, Xu D, Baraban SC, Rubenstein JL (2014) NPAS1 represses the generation of specific subtypes of cortical interneurons. Neuron 84:940-53. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura N, Nakagawa S, Masuda T, Boku S, Kato A, Song N, An Y, Kitaichi Y, Inoue T, Koyama T, Kusumi I (2014) The effect of dopamine on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 50:116-24. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X, Finkbeiner S, Arnold DB, Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME (1998) Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron 20:709-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X, West AE, Chen WG, Corfas G, Greenberg ME (2002) A calcium-responsive transcription factor, CaRF, that regulates neuronal activity-dependent expression of BDNF. Neuron 33:383-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Hu K, Chang Q, Wu H, Sherman NE, Martinowich K, Klose RJ, Schanen C, Jaenisch R, Wang W, Sun YE (2009) Phosphorylation of MeCP2 at Serine 80 regulates its chromatin association and neurological function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:4882-4887. 10.1073/pnas.0811648106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teh DB, Ishizuka H, Yawo H (2014) Regulation of later neurogenic stages of adult-derived neural stem/progenitor cells by L-type Ca channels. Dev Growth Differ 56:583-594. 10.1111/dgd.12158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesla R, Wolf HP, Xu P, Drawbridge J, Estill SJ, Huntington P, McDaniel L, Knobbe W, Burket A, Tran S, Starwalt R, Morlock L, Naidoo J, Williams NS, Ready JM, McKnight SL, Pieper AA (2012) Neuroprotective efficacy of aminopropyl carbazoles in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:17016-21. 10.1073/pnas.1213960109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Rivera PD, Wang Q, Chuang JC, Tran S, Osborne-Lawrence S, Estill SJ, Starwalt R, Huntington P, Morlock L, Naidoo J, Williams NS, Ready JM, Eisch AJ, Pieper AA, Zigman JM (2015) The P7C3 class of neuroprotective compounds exerts antidepressant efficacy in mice by increasing hippocampal neurogenesis. Mol Psychiatry 20:500-508. 10.1038/mp.2014.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Han T, Nijhawan D, Theodoropoulos P, Naidoo J, Yadavalli S, Mirzaei H, Pieper AA, Ready JM, McKnight SL (2014) P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals function by activating the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD salvage. Cell 158:1324-1334. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessa M, Linke J, Witt SH, Nieratschker V, Esslinger C, Kirsch P, Grimm O, Hennerici MG, Gass A, King AV, Rietschel M (2010) The CACNA1C risk variant for bipolar disorder influences limbic activity. Mol Psychiatry 15:1126-1127. 10.1038/mp.2009.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Pruunsild P, Timmusk T (2014) Neurotrophic factors: handbook of experimental pharmacology, Vol220, (Lewin GR, Carter BD, eds). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- White JA, McKinney BC, John MC, Powers PA, Kamp TJ, Murphy GG (2008) Conditional forebrain deletion of the L-type calcium channel CAv1.2 disrupts remote spatial memories in mice. Learn Mem 15:1-5. 10.1101/lm.773208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Li Y, Xiao B (2013) DISC1-related signaling pathways in adult neurogenesis of the hippocampus. Gene 518:223-230. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin TC, Britt JK, De Jesus-Cortés H, Lu Y, Genova RM, Khan MZ, Voorhees JR, Shao J, Katzman AC, Huntington PJ, Wassink C, McDaniel L, Newell EA, Dutca LM, Naidoo J, Cui H, Bassuk AG, Harper MM, McKnight SL, Ready JM, Pieper AA (2014) P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals block axonal degeneration and preserve function after traumatic brain injury. Cell Rep 8:1731-1740. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Patchev AV, Wu Y, Lu J, Holsboer F, Zhang JZ Sousa N, Almeida OF (2010) Depletion of the neural precursor cell pool by glucocorticoids. Ann Neurol 67: 21–30. 10.1002/ana.21812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]