Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to establish the psychometric properties of 22 measures from a community-based participatory research (CBPR) conceptual model.

Design

On-line, cross-sectional survey of academic and community partners involved in a CPBR project

Setting

294 CPBR projects in the U.S. with federal funding in 2009

Subjects

312 (77.2% of 404 invited) academic and community partners and 138 principal investigators/project directors (69.0% of 200 invited)

Measures

22 measures of CBPR context, group dynamics, methods, and health-related outcomes

Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis to establish factorial validity and Pearson correlations to establish convergent and divergent validity

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated strong factorial validity for the 22 constructs. Pearson correlations (p < .001) supported the convergent and divergent validity of the measures. Internal consistency was strong with 18 of 22 measures achieving at least a .78 Cronbach’s alpha.

Conclusion

CBPR is a key approach for health promotion in underserved communities and/or communities of color and yet the basic psychometric properties of CBPR constructs have not been well established. This study provides evidence of the factorial, convergent, and discriminant validity, and internal consistency of 22 measures related to the CBPR conceptual model. Thus, these measures can be used with confidence by both CBPR practitioners and researchers to evaluate their own CBPR partnerships and advance the science of CBPR.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, community-engaged research, partnership dynamics, health outcomes, research partnerships, underserved populations, communities of color

Indexing Key Words: Manuscript format: research; Research purpose: instrument development; Study design: non-experimental; Outcome measure: behavioral, cognitive; Setting: state/national; Health focus: social health; Strategy: skill building/behavior change; Target population age: Adults; Target population characteristics: academic and community members who partner to address health promotion with underserved communities and/or communities of color

PURPOSE

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a growing science for engaging in health promotion that especially addresses health disparities through partnership of researchers and community members in all phases of the research.1-3 CBPR and community-engaged research are widely accepted by public health practitioners and academic researchers as effective in working with underserved communities and communities of color because they help to establish trust with community members who may feel disenfranchised, enhance cultural appropriateness of methods/interventions, and build capacity of university partners and community members.4-7

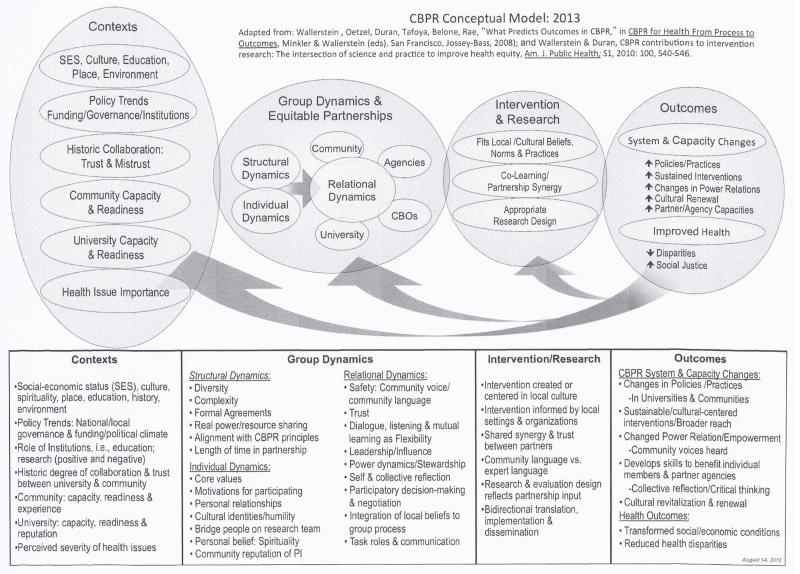

Despite the growing interest, the science of CBPR has lagged behind its practice. In recent years, the development of theoretical models has enhanced the understanding of the pathways by which CBPR processes results in particular outcomes. First, Wallerstein and her colleagues2 developed a conceptual model of CBPR that includes four domains: context, group dynamics, intervention/research, and outcomes (system/capacity and health outcomes) (see Figure 1). The model was developed in consultation with a national advisory board of CBPR community and academic experts and identifies specific characteristics within each domain, drawing upon prior work identifying CPBR constructs.8 Context includes socio-economic, policy, historical collaboration, and community/university capacity which provide the background for the group dynamics. Group dynamics includes structural features of the partnership, individual characteristics, and the relational dynamics among members. The partnering processes shape the intervention or research design and ideally reflect mutual learning and local community norms and practices. Finally, the intervention/research produces outcomes for the community and individual members.

Figure 1.

CBPR conceptual model

Second, Khodyakov and colleagues9 developed a model that explained how partnership characteristics result in outcomes such as the synergy of the partnership, partnership size, and community engagement in the research. In a study of 62 community and academic leaders of 21 federally-funded research centers on mental health, the authors found that community engagement in research was positively associated with professional development of members and community/policy-level outcomes. Synergy was associated positively with capacity building and community/policy-level outcomes. The two models are similar in perspective although the Wallerstein et al. model is more comprehensive in its coverage by including aspects of context and intervention/research. However, the current study benefited from Khodyakov et al.’s partnership measures.

The gains in theorizing and modeling are important for the science of CBPR. However, while the core constructs have been identified, there is a lack of strong measurement of these constructs. A review of literature on measurement tools of community coalitions revealed that the majority lacked information about validity and reliability.10 To prepare for the study reported here, the research team11 reviewed 273 articles using CBPR and identified 46 instruments with 224 measures of CBPR constructs within the CBPR conceptual model.2 They found that only 54 measures had evidence of internal consistency and only 31 had any evidence of validity. The validity tended to focus only on expert opinions or exploratory factor analysis. Thus, the vast majority of measures lack the basic psychometric properties expected of rigorous social science. Further, most of the measures focus on relational dynamics with many of the domains and constructs in the conceptual model not being measured. With the widespread use of CPBR, it is imperative to advance the quality of the measurement of partnership processes and outcomes.

A recent study offers stronger evidence of measurement quality than most previous studies.4, 9 This study offered evidence of internal consistency and factorial validity (exploratory factor analysis) for 10 measures of processes and outcomes including the following: perceived community and policy-level outcomes, capacity building, partnership synergy, influence in decision making, leadership, and managing partnership activities. Despite this improvement, there are several limitations of their study: small sample size (only 62 respondents from 21 projects), similar types of projects (all focusing on mental health), and inclusion of a partial set of constructs consistent with the CBPR conceptual model.

In summary, in order to develop the science of CBPR, there needs to be rigorous measurement of constructs in the CBPR conceptual model. Without rigorous measurement, researchers are not able to test the pathways of the conceptual model and practitioners are not able to effectively evaluate their partnership. Thus, the purpose of the current study is to provide evidence of the psychometric properties (internal consistency, factorial validity, and convergent/discriminant validity) of 22 measures used in a national survey of partners from 294 federally-funded CBPR or community-engaged research projects. These 22 measures cover many, but not all, of the constructs within the four domains as the conceptual model simply has too many constructs to effectively measure in single study. Choices were made as to the most important constructs and what could be measured in this study and are elaborated on in the measures section.

METHODS

Design

The research design is a three-stage, cross-sectional survey of federally-funded CBPR projects. The current study is based on the 3rd stage. A brief summary of the first two stages is described here in order to provide sufficient background. Further details on the first two stages can be found elsewhere.7,12 All data were collected via DatStat Illume, a web-based survey platform.

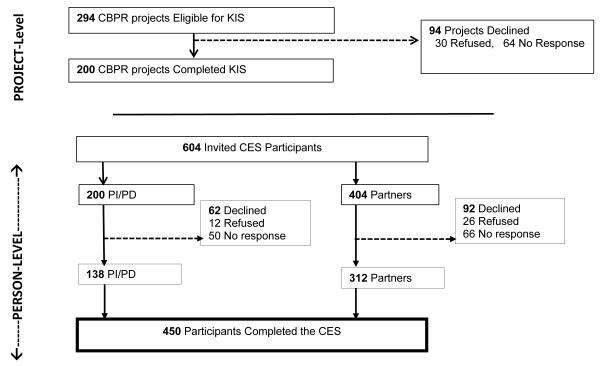

First, 103,250 federally-funded extramural projects funded in 2009 were screened using a computer algorithm and staff review to identify projects that involved CBPR or community-engaged research and included a range of institutes, funding agencies, health topics, and funding mechanisms (citation added after review); 333 were identified and invited to participate in the study. Second, among the invited projects, only 294 actually involved CBPR or community-engaged research (based on self-identification or re-screening of non-participating abstracts); 200 (68.0%) of the principal investigators/project directors (PI/PD) participated in a key informant survey (KIS) in the latter part of 2011. The KIS asked the PI/PD to identify project characteristics and also up to four individuals (one academic partner and three community partners) to participate in the third stage, the community engagement survey (CES). In addition, the PI/PD was invited to complete the CES and to nominate community partners to complete the CES. This survey included the measures evaluated in the current study and took about 30 minutes to complete. Survey follow-up included five e-mail reminders and contact via phone as needed. The study protocol was approved by two university IRBs and the National Indian Health Service IRB.

Sample

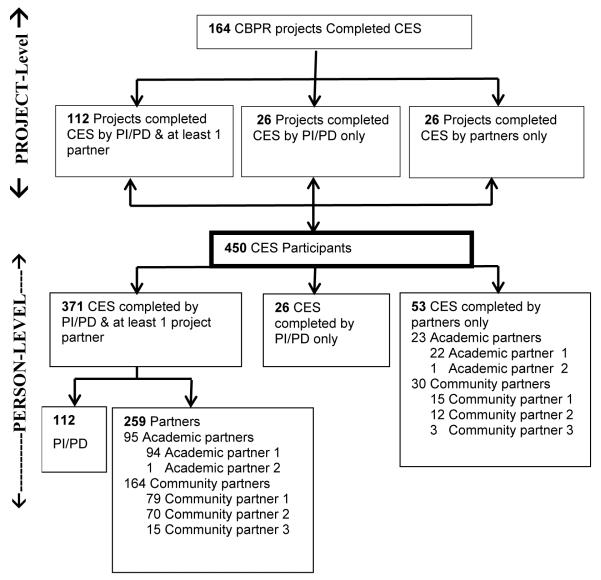

The PI/PD nominated a total of 404 partners with 312 completing the survey in 2012. Of the 200 eligible PI/PD’s, 138 completed the CES. These 450 participants represented 82% of the total projects where a KIS was completed and 56% of the original 294 projects. The CES sample included the following demographic characteristics (with missing data accounting for totals not adding to 450): a) 118 academic and 194 community partners; b) 205 female and 73 male, and c) 272 White, non-Hispanic, 37 American Indian/Alaska Native, 37 African American, 32 Hispanic, 28 Asian/Pacific Islander, and 23 mixed race or other. Figure 2 displays the flowchart of the stages and includes the reasons people did not participate. Figure 3 displays the number of responding projects and individuals per project.

Figure 2.

Selection flow chart of the community engagement survey

PI/PD = Principle investigators or project directors, KIS= key informant survey; CES = community engagement survey; Bolded box includes the sample for this study

Figure 3.

Community engagement survey (CES) flow chart for projects and participants

PI/PD = Principle investigators or project directors, CES= community engagement survey; Bolded box includes the sample for this study

Measures

The selection of measures and writing items for new measures were developed in the following manner. First, the literature on measures of CPBR and community-engaged research constructs within the conceptual model was consulted with a focus on which measures had evidence of validity and reliability. Thus, we began with the list of 224 measures noted in the purpose section. Second, the research team consulted with a team of CBPR experts for advice on measurement and research design. This advisory group was used to help determine the most important constructs and domain within the conceptual model, especially given constraints of survey length. Third, the survey was part of a larger study that included seven in-depth case studies of CBPR projects. Three of those case studies were completed before the initiation of the survey and thus helped to inform item generation for constructs without prior measures. These steps allowed for the creation of items of face and content validity consistent with the CBPR conceptual model. Further, areas where the case studies could better address the constructs were identified and left off the survey (i.e., many context and research design constructs). Fourth, the surveys used in this study were piloted with CBPR projects not funded in 2009 and this information was used to revised item wording and improve the flow of the on-line survey, and ensure the participant burden in completing the survey was reasonable. The large number of measures and items is appropriate given the breadth of CBPR and community-engaged research.

The measures included a total of 101 items. The first two columns in the tables presented in the results section help to organize the domain and measures described here. For context, seven items measuring the capacity of the partnership to meet its aims were included.10 In addition, a single item that was created for this study measured the degree of trust at the beginning of the partnership, which distinguishes from current levels of trust.

There were three measures of structural/individual dynamics. There were two new measures created for this study: “bridging social capital” (3 items) assessed the ability of community and academic members to work effectively with each other, and “alignment with CBPR principles” consisted of two sub-scales (partner and community focus; 4 items each) and was constructed from Israel et al.’s3 principles of effective CBPR and consistent with a recent conceptualization of principles.13 Finally, “partner values” (4 items) captures the degree to which there is agreement with the mission and strategies of the project.14

There were 11 measures of relational dynamics. They include the following: “research tasks and communication” consisting of three subscales that capture level of involvement for community partners in various stages of the research process—background (5 items), data collection (4 items), and analysis & dissemination (4 items);9 “Dialogue and mutual learning” consisting of tree subscales participation, cooperation, and respect (3 items each).15 “Trust” (4 items);16 “influence and power dynamics” (3 items);17 “participatory decision making”;9 “Leadership” effectiveness (12 items),9 and “resource management” (3 items; labeled efficiency in the original).9

In the final domains, intervention and outcomes, there were seven measures. For intervention, the degree to which the partnership had “synergy” was employed (5 items).9 Outcomes include “system and capacity changes” with four scales. Partner capacity building (4 items) was from an existing scale and agency capacity building (4 items) was from the same existing scale, but re-written for an agency instead of an individual 9 and “changes in power relations” (5 items) and “sustainability of partnership/project” (3 items) were created for this study. There were also two scales measuring more distal outcomes: “community transformation” (7 items) from an existing scale9 and “community health improvement” (1 item) created for this study.

Some of the original measures cited were altered for the purpose of the current study (i.e., to fit the CBPR conceptual model) and because of concerns about the length of the survey for participants. Specifically, the following changes were made: (a) capacity items were from an original scale that was labeled non-financial resources with subscales of social and human capital;9 (b) task communication included one additional item and the items were also divided into three subscales to reflect different phases in the research process whereas the original items were written as a single scale (community-engagement in research index);4, 9 (c) dialogue and mutual learning measures included only 3 items from the original measures of 5 (participation), 7 (cooperation), and 5 (respect) items;15 (d) participatory decision making items were from the original scale of decision making with two subscales of inclusion and exclusion from decision making;9 (e) synergy included only 5 of the original 11 items;9 (f) partner capacity building included only 4 of the original 11 items that were part of three subscales related to personal outcomes in the original;9 and (g) community transformation included 2 items written for this study to add to the original 5 items of a scale originally labeled perceived community/policy-level benefits.9 Thus, the revised measures cannot be considered an empirical validation of the original scales.

Analyses

To address factorial validity, all measures were analyzed with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using SPSS AMOS 20.0 in 2013. The CFAs were completed using the following protocol. First, all missing values were replaced with series mean; while replacing data in this manner can be problematic, missing data was determined to be missing at random with a very small portion of missing values in the entire data set (< 1%) and hence is not a major concern. Second, the individual measures were assessed using three fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean squared residual (RMR). Good fit was determined if CFI and TLI were at or above .90 and RMR was less than .08. If all three fit indices were not acceptable, measures were modified by removing items. Items were removed if there was a suggested modification of correlating error terms or suggested path to another item. In these cases, the item that had the largest modification impact was removed. The modification of measures is controversial and cautioned against by some.18 However, as this is the first study to validate a number of CBPR measures and there is a large and robust sample of CBPR projects, it seems reasonable to explore the factor structure if good fit was not achieved. To mitigate the concern of modifying measures, the sample was split into two random halves. The measure was modified with the first random sample; the second random sample was used to confirm the modifications. This approach allows for a confirmation of the modifications. Third, once all of the individual measures were confirmed, an additional CFA for measures within particular domains of the CBPR model was completed. In the case of relational dynamics, there were several multiple factor models given the large number of measures in this domain. These multiple factor models allow for further testing of the factorial validity of the scales. Finally, since the partners are nested within partnerships, the factors loadings and structural covariances of these multiple factor models were tested for measurement invariance by comparing a random selection of one partner in each partnership to the other remaining partners. All of these models had evidence of invariance and thus only the results for the entire sample are presented.

After completing the factor analysis, internal consistency of the measures was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha. Further, means and standard deviations of the averaged items were calculated. Finally, a correlation matrix was constructed to address construct validity. All of these analyses were completed with SPSS 20.0.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the results of the CFAs and includes information on the fit indices on unmodified measures, modified measures (where relevant), and multiple factor CFAs. All tables include 22 multi-item measures and 2 single-item measures that are displayed because of their use in construct validity. The results focus primarily on the analysis of the 22 multi-item measures. Of the 22 multi-item measures, 15 of the measures achieved good fit without any modification. An additional two measures (partner capacity building and agency capacity building) also had good fit without modification, but had to be modified in order to achieve a good multiple-factor model. Five measures needed to have one item removed to achieve good model fit (project capacity, task analysis & dissemination, participatory decision-making, partner capacity building, and agency capacity building). One measure needed two items removed (leadership) and one measure needed three items removed (community transformation).

Table 1.

Psychometric properties of measures

| Domain | Name of Measure | Number of Items and Range |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Mean | SD | Factorial Validity (single construct- unmodified) |

Factorial Validity (single construct- modified) |

Factorial Validity (multiple constructs within a domain) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context |

Project capacity. Project has the resources it needs to meet its aims |

6 modified; 7 original (1-5) |

0.78 | 4.34 | 0.52 | χ2(14) = 89.35, p < .001; CFI = .91, TLI = .87, SRMR = .03 |

χ2(9) = 20.88, p = .013, CFI = .96, TLI = .93, SRMR = .03 |

N/A |

|

Initial trust. Level of trust at the beginning of the partnership |

1 (1-7) | N/A | 5.21 | 1.26 | N/A | N/A | ||

|

Structural/

Individual Dynamics |

Bridging social capital. Academic and community partners have the skills and cultural knowledge to interact effectively |

3 (1-5) | 0.69 | 4.16 | 0.70 | Saturated model | Not modified | χ2(84) = 206.27, p < .001, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, SRMR = .03 |

|

Alignment with CBPR principles: Partner focus. Develops individual partner capacity and equitable partnerships in all phases of the research |

4 (1-5) | 0.82 | 4.51 | 0.59 | χ2(2) = 0.65, p = .724, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, SRMR = .003 |

Not modified | ||

|

Alignment with CBPR principles: Community focus. Builds on resources and strengths of the community for the well-being of the community |

4 (1-5) | 0.85 | 4.30 | 0.67 | χ2(2) = 3.58, p = .167, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, SRMR =.01 |

Not modified | ||

|

Core values. Shared understanding of the project mission, priorities, and strategies |

4 (1-5) | 0.89 | 4.41 | 0.60 | χ2(2) = 27.77, p < .001, CFI = .98, TLI = .93, SRMR = .01 |

Not modified | ||

|

Relational

Dynamics |

Task roles and communication: Background research. Community partners' level of involvement in the background research |

5 (1-3) | 0.81 | 2.07 | 0.57 | χ2(5) = 35.49, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .91, SRMR =.02 |

Not modified | χ2(51) = 93.12, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .93, SRMR = .03 |

|

Task roles and communication: Data collection. Community partners’ level of involvement in the data collection |

4 (1-3) | 0.69 | 2.50 | 0.51 | χ2(2) = 11.61, p = .003, CFI = .97, TLI = .90, SRMR = .02 |

Not modified | ||

|

Task roles and communication: Analysis & Dissemination. Community partners' level of involvement in data analysis and dissemination of findings |

3 modified; 4 original (1-3) |

0.82 | 2.07 | 0.71 | χ2(2) = 60.89, p < .001, CFI = .92, TLI = .77, SRMR = .03 |

Saturated model | ||

|

Dialogue and mutual learning: Participation. Degree to which all partners participate in the process |

3 (1-5) | 0.78 | 4.44 | 0.58 | Saturated model | Not modified | χ2(59) = 160.48, p < .001, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, SRMR = .03 |

|

|

Dialogue and mutual learning: Cooperation. Degree to which partners cooperate to resolve disagreements |

3 (1-5) | 0.83 | 4.15 | 0.68 | Saturated model | Not modified | ||

|

Dialogue and mutual learning: Respect. Degree to which partners convey respect to each other (low score equals higher respect) |

3 (1-5) | 0.83 | 1.74 | 0.89 | Saturated model | Not modified | ||

|

Trust. Degree of current trust within the partnership |

4 (1-5) | 0.86 | 4.36 | 0.63 | χ2(2) = 8.80, p = .012, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, SRMR = .01 |

Not modified | ||

|

Influence and power dynamics. Degree of voice and influence in the decision making |

3 (1-5) | 0.58 | 3.79 | 0.71 | Saturated model | Saturated model | χ2(13) = 41.35, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .93, SRMR = .04 |

|

|

Participatory decision making. Degree to which decisions are made in a participatory manner |

4 modified; 5 original (1-5) |

0.83 | 4.03 | 0.62 | χ2(5) = 116.01, p < .001, CFI = .89, TLI = .78, SRMR = .05 |

χ2(2) = 12.63, p = .002, CFI = .97, TLI = .92, SRMR = .02 |

||

|

Leadership. Overall effectiveness of project's leadership |

10 modified; 12 original (1-5) |

0.94 | 4.28 | 0.61 | χ2(54) = 455.78, p < .001, CFI = .91, TLI = .89, SRMR = .03 |

χ2(35) = 139.84, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .92, SRMR = .03 |

χ2(64) = 171.09, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, SRMR = .02 |

|

|

Stewardship. Effective use of financial & in-kind resources |

3 (1-5) | 0.86 | 4.36 | 0.65 | Saturated model | Not modified | ||

|

Intervention/

Research |

Partnership synergy. Partners ability to develop goals, recognize challenges, respond to needs, and work together |

5 (1-5) | 0.90 | 4.46 | 0.59 | χ2(5) = 33.27, p < 001, CFI = .98, TLI = .96, SRMR = .01 |

Not modified | N/A |

| Outcome |

Systems and capacity changes: Partner capacity building. Develops the skills to benefit the individual members |

3 modified; 4 original (1-5) |

0.80 | 3.42 | 0.99 | χ2(2) = 6.45, p = .040, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, SRMR = .02 |

Saturated model | χ2(125) = 255.59, p < .001, CFI = .93, TLI = .92, SRMR = .07 |

|

Systems and capacity changes: Agency capacity building. Develops the reputation and skills of agencies involved in the partnership |

3 modified; 4 original (1-5) |

0.87 | 3.54 | 0.96 | χ2(2) = 18.83, p < .001, CFI = .98, TLI = .94, SRMR = .04 |

Saturated model | ||

|

Systems and capacity changes: Changes in power relations. Degree to which power and capacity has been developed in the community members |

5 (1-5) | 0.81 | 4.17 | 0.60 | χ2(5) = 12.74, p = .026, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, SRMR = .01 |

Not modified | ||

|

Systems and capacity changes: Sustainability of partnership/project. Likelihood of the project and partnership continuing beyond the funding period |

3 (1-5) | 0.71 | 4.00 | 0.76 | Saturated model | Not modified | ||

|

Health outcomes: Community transformation. Policy changes and community improvement. |

4 modified; 7 original (1-5) |

0.79 | 2.92 | 1.00 | χ2(14) = 122.08, p < .001, CFI = .92, TLI = .87, SRMR = .09 |

χ2(2) = 7.37, p = .025, CFI = .98, TLI = .95, SRMR = .06 |

||

|

Health outcomes: Community health improvement. Improvement of health for the community as a result of the project |

1 (1-5) | N/A | 3.63 | 1.02 | N/A | N/A |

The multiple-factor models provide further support of the factorial validity of the measures. In most cases, the multiple-factor models confirmed the original measures without any need for further modification. For the outcome domain, the multiple-factor model did not achieve a good fit initially, χ2(179) = 839.04, p < .001, CFI = .86, TLI = .84, SRMR = .08. A single item from the partner and agency capacity building were removed and good model fit was achieved..

Table 1 also displays descriptive information about each of the measures. The internal consistency of the measures was generally very good. Only one measure failed to reach the minimum threshold of .60 (influence and power dynamics at .58), while most of the measures were at or above .78 (18 of 22). The individual items and factors loadings are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Items and factor loadings

| Domain | Name of Scale | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Project capacity |

|

| Initial trust |

|

|

| Structural/ Individual Dynamics |

Bridging social capital |

|

|

Alignment with CBPR

principles: Partner focus |

|

|

|

Alignment with CBPR

principles: Community focus |

|

|

| Core values |

|

|

| Relational Dynamics |

Task roles and

communication: Background research |

|

|

Task roles and

communication: Data collection |

|

|

|

Task roles and

communication: Analysis & Dissemination |

|

|

|

Dialogue and mutual

learning: Participation |

|

|

|

Dialogue and mutual

learning: Cooperation |

|

|

|

Dialogue and mutual

learning: Respect |

|

|

| Trust |

|

|

|

Influence and power

dynamics |

|

|

|

Participatory decision

making |

|

|

| Leadership |

|

|

| Stewardship |

|

|

| Intervention / Research |

Partnership synergy |

|

| Outcome |

Systems and capacity

changes: Partner capacity building |

|

|

Systems and capacity

changes: Agency capacity building |

|

|

|

Systems and capacity

changes: Changes in power relations |

|

|

|

Systems and capacity

changes: Sustainability of partnership/project |

|

|

|

Health outcomes:

Community transformation |

|

|

|

Health outcomes:

Community health improvement |

|

Table 3 displays the correlation matrix. This matrix helps to support the construct validity of the measures by offering information specifically about convergent and discriminant validity. First, the measures for constructs within domains generally demonstrate positive and moderate correlations. One exception is that within the relational dynamics domain, lack of respect was negatively and moderately correlated with other measures in this domain. These expected patterns illustrate that the measures have good convergent validity. Second, measures for constructs across domains, but that should be related, are positively and moderately correlated. For example, the principles measures are positively associated with the degree to which community partners were involved in the task roles (background, data collection, and analysis & dissemination) in the partnership. This pattern is further evidence of convergent validity. Finally, there is also good convergent and discriminatory validity for the relational dynamics measures and outcomes. A positive relationship between partnering behaviour and outcomes is expected. However, some outcomes should be better predicted than others. Specifically, improved health is a distal outcome that would not be expected to be largely associated with specific partnering behavior. In contrast, most of the other outcomes are proximal or intermediate to the partnership and thus would be expected to have a stronger and positive relationship with relational dynamics compared to improved health. The matrix supports this pattern with small to insignificant correlations for relational dynamics and improved health and moderate and positive relationships for relational dynamics and the other outcomes.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of measures

| Domain | Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | 1. Project Capacity |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Initial Trust | .16* | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Structural/Individual

Dynamics |

3. Bridging social capital |

.44* | .21* | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Principles: Partner |

.53* | .14 | .53* | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Principles: Community |

.51* | .18* | .48* | .74* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Core Values | .49* | .18* | .49* | .64* | .64* | |||||||||||||||||||

| Relational Dynamics | 7. Task Background |

.25* | .10 | .22* | .38* | .41* | .28* | |||||||||||||||||

| 8. Task Data Collection |

.16* | .01 | .12 | .36* | .31* | .30* | .56* | |||||||||||||||||

| 9. Task Analysis & Dissemination |

.15 | −.01 | .10 | .28* | .31* | .21* | .65* | .59* | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Participation | .35* | .20* | .36* | .43* | .50* | .54* | .23* | .17* | .19* | |||||||||||||||

| 11. Cooperation | .20* | .10 | .22* | .32* | .38* | .41* | .26* | .24* | .23* | .53* | ||||||||||||||

| 12. (Dis)Respect | −.13 | −.12 | −.23* | −.23* | −.26* | −.37* | −.06 | −.02 | −.01 | −.43* | −.24* | |||||||||||||

| 13. Trust | .43* | .21* | .44* | .54* | .57* | .64* | .26* | .24* | .22* | .51* | .40* | −.34* | ||||||||||||

| 14. Influence | .32* | .16* | .27* | .44* | .54* | .48* | .51* | .38* | .46* | .44* | .42* | −.19* | .59* | |||||||||||

| 15. Participatory Decision Making |

.37* | .21* | .41* | .52* | .55* | .61* | .24* | .21* | .19* | .55* | .37* | −.40* | .63* | .56* | ||||||||||

| 16. Leadership | .50* | .18* | .52* | .59* | .68* | .67* | .28* | .20* | .18* | .67* | .46* | −.39* | .68* | .50* | .65* | |||||||||

| 17. Stewardship | .40* | .13 | .35* | .46* | .51* | .52* | .24* | .23* | .18* | .47* | .32* | −.26* | .58* | .36* | .50* | .59* | ||||||||

| Research | 18. Synergy | .49* | .17* | .51* | .59* | .61* | .65* | .30* | .27* | .22* | .59* | .40* | −.33* | .60* | .43* | .59* | .76* | .60* | ||||||

| Outcomes | 19. Partner Capacity Building |

.33* | .15 | .27* | .36* | .37* | .33* | .26* | .29* | .24* | .25* | .28* | −.05 | .38* | .41* | .33* | .39* | .41* | .39* | |||||

| 20. Agency Capacity Building |

.38* | .11 | .34* | .49* | .48* | .39* | .29* | .30* | .28* | .31* | .31* | −.13 | .40* | .42* | .32* | .46* | .39* | .49* | .68* | |||||

| 21. Change in power relations |

.33* | .13 | .30* | .52* | .56* | .44* | .49* | .49* | .46* | .43* | .36* | −.13 | .50* | .52* | .45* | .48* | .43* | .52* | .44* | .53* | ||||

| 22. Sustainability | .38* | .18* | .28* | .47* | .52* | .40* | .38* | .32* | .33* | .35* | .29* | −.10 | .46* | .47* | .41* | .43* | .40* | .48* | .45* | .49* | .58* | |||

| 23. Community transformatio n |

.28* | .01 | .29* | .32* | .30* | .25* | .23* | .24* | .22* | .21* | .20* | −.01 | .28* | .32* | .21* | .30* | .31* | .35* | .39* | .50* | .33* | .39* | ||

| 24. Improved community health |

.27* | .09 | .32* | .34* | .36* | .29* | .14 | .14 | .07 | .21* | .20* | −.06 | .30* | .29* | .22* | .36* | .30* | .40* | .59* | .36* | .51* | .30* | .38* |

p <.001

DISCUSSION

There are several strengths of this study that contribute to the science of CBPR. First, this study is the first large scale study of CBPR projects in the U.S. Prior studies of CBPR processes and outcomes have looked at a small number of, or single, projects.19, 20 Even when there have been a larger number of projects involved,9 the projects were limited to a similar health condition. The current study involves a rigorous three-stage random sampling of CBPR or community-engaged research projects across the United States. The response rates were generally high for every component of the sampling process; thus, the findings have some generalizability to the CBPR and community-engaged research community.

Second, this study provides evidence of the factorial, convergent, and discriminant validity and internal consistency of 22 measures related to the CBPR conceptual model.2 This evidence makes a significant contribution to the CBPR literature given the limited information on measurement validity and reliability of CBPR measures noted by prior reviews.10, 11 The vast majority of prior CBPR studies have utilized measures that have not been adequately tested and thus conclusions can be called into question. The current measures have strong psychometric properties that researchers can use to measure relevant constructs in the CBPR conceptual model. Of particular note is that the measures include proximal (synergy), intermediate (partner and agency capacity building, changes in power relations, and sustainability), and distal outcomes (community transformation and improving community health) that can be used for testing relationships among context, processes, and outcomes. In addition, the research team is in the process of developing an additional proximal outcome called culture centeredness21 that combines some of the validated scales for a measure of the level of voice and involvement of community partners and a trust typology that characterizes the process of trust over time.22

In addition to contributing to the science of CBPR, this study has strong practical implications. A key component of CBPR is the ability to self-reflect and self-assess partnering processes and outcomes.23 Community and academic partners want to use measures that are simple, and yet valid, assessments and evaluations of their partnering processes and outcomes. These measures have strong measurement validity and yet are straightforward. There is a website that includes the original survey instruments and their instructions and scaling so that interested partners can access and implement them in their own partnerships (web site to be added after review of the manuscript). These measures were designed to be a comprehensive list of processes and outcomes that community and academic partners can select from as they fit to their project. A good approach would be to focus on the outcomes that the project wants to achieve and then explore other measures that are most strongly correlated with those outcomes (i.e., in Table 3). Ideally all of the items in a measure would be used and yet space constraints may limit how many can be selected. In that case, selecting at least three items with the highest factor loadings is recommended.

The current study has a few limitations. First, there were some modifications in a few measures in order to achieve good model fit. Future research may be needed to examine the psychometric properties of these measures further. Some items did not make the final fit into the scales, but may be still useful for partnerships to collect as single items. For example, the item on “improved health services” was removed possibly because of our community-based research sample, but might be useful for health services partnerships. In addition, the sampling frame only included funded CBPR projects identified as CBPR or community-engaged research. This approach is reasonable given the research aims, yet the result may be less applicability for research projects with limited community engagement. Similarly, the study did not make comparisons to non-CBPR projects so that concurrent validity could not be established. Further, given the constraints of research design and resources, there was not any level of predictive validity of the measures; the psychometric properties are based solely on self-report data and not actual behaviour. Finally, the study included limited measures of particularly “context” and “intervention/research design” as it was difficult to identify measures that could be used across a variety of CBPR projects. Specifically, several measures that should be developed in the future include policy and funding context, historical collaboration, community and university readiness, fit of research to local/cultural norms and practices, and cultural renewal. The larger project included seven in-depth case studies that emphasized contextual and research design issues and yet is beyond the scope of this article.

In summary, despite these limitations, the current study provides evidence of the psychometric properties of 22 measures related to the CBPR conceptual model. The research design included strong response rates for two stages of surveys to provide further confidence in these data. While some modifications of the original measures were necessary to achieve model fit, there was a rigorous process of modifying and confirming the modifications with two random samples of the data. These steps strongly support the use of the measures by academic and community partners to evaluate and advance their own CBPR practice as a promising strategy for engaging in health promotion to address health disparities in underserved and minority communities. This study helps to establish the measurement validity of scales that can help to advance the practice and science of CBPR.

SO WHAT?

What is already known about this topic?

CBPR and other forms of community-engaged research are well accepted approaches to engage in health promotion to address health disparities in underserved communities and/or communities of color.

What does this article add?

While CBPR and community-engaged research are well accepted, there is a lack of understanding about how and why these approaches have positive outcomes. In order to better understand how CBPR works, good measurement of CBPR processes and outcomes is needed. This article offers 22 scales that are good measures of these processes and outcomes.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

These measures can be used by practitioners to help evaluate their partnership which enables them to engage in self-reflection and identify strengths and areas for improvement. In addition, these measures will enable researchers to better understand the “best practices” of CBPR and to identify the reasons why CBPR works (and perhaps when it does not).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Belone L, Tafoya G, Rae R. CBPR: What predicts outcomes? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participary research for health: From process to outcomes. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones A, Mango J, Jones F, Lizaola E. On measuring community participation in research. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):346–54. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community-partnered cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or resources for services to address depression disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(10):1268–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda J, Ong MK, Jones L, et al. Community-partnered evaluation of depression services for clients of community-based agencies in under-resourced communities in Los Angeles. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(10):1279–1287. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks S, Duran B, Wallerstein N, et al. Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(3):289–99. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Lantz P. Instrument for evaluating dimensions of group dynamics within community-based participatory research partnerships. Eval Program Plann. 2003;26(3):249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F, et al. An exploration of the effect of community engagement in research on perceived outcomes of partnered mental health services projects. Soc Ment Health. 2011;1(3):185–199. doi: 10.1177/2156869311431613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granner ML, Sharpe PA. Evaluating community coalition characteristics and functioning: a summary of measurement tools. Health Educ Res. 2004;19(5):514–532. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandoval JA, Lucero J, Oetzel J, et al. Process and outcome constructs for evaluating community-based participatory research projects: a matrix of existing measures. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):680–90. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearson C, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Magarati M, Villegas M, Lucero J. Research for improved health: variability and impact of structural characteristics in federally-funded community-engaged research projects. Prog Community Health Partnersh. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun KL, Nguyen TT, Tanjasiri SP, et al. Operationalization of community-based participatory research principles: assessment of the national cancer institute's community network programs. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allies again asthma evaluation instrument. Univesity of Michigan Center for Managing Chronic Disease; Ann Arbor, MI: 2003. Allies against Asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oetzel JG. Self-construals, communication processes, and group outcomes in homogeneous and heterogeneous groups. Small Group Research. 2001;32(1):19–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figueroa ME, Kincaid DL, Rani M, Lewis G. Communication for social change: an integrated model for measuring the process and its outcomes. The Rockefeller Foundation; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Israel BA, Checkoway B, Schulz A, Zimmerman M. Health education and community empowerment: conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(2):149–70. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed The Guilford Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheatham-Rojas A, Shen E. CBPR with Cambodian girls in Long Beach, California: A case study. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from processes to outcomes. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shepard P, Vasquez V, Minkler M. Using CBPR to promote environmental justice policy: a case study from Harlem, New York. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research: from processes to outcomes. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta MJ. Communicating about culture and health: theorizing culture - centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun Theory. 2007;17(3):304–328. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucero J. Trust as an ethical construct in community based participatory research partnerships [dissertation] University of New Mexico; Albuquerque, NM: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, Calif: 2012. [Google Scholar]