Abstract

Background

Athletic groin pain remains a common field-based team sports time-loss injury. There are few reports of non-surgically managed cohorts with athletic groin pain.

Aim

To describe clinical presentation/examination, MRI findings and patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores for an athletic groin pain cohort.

Methods

All patients had a history including demographics, injury duration, sport played and standardised clinical examination. All patients underwent MRI and PRO score to assess recovery. A clinical diagnosis of the injured anatomical structure was made based on these findings. Statistical assessment of the reliability of accepted standard investigations undertaken in making an anatomical diagnosis was performed.

Result

382 consecutive athletic groin pain patients, all male, enrolled. Median time in pain at presentation was (IQR) 36 (16–75) weeks. Most (91%) played field-based ball-sports. Injury to the pubic aponeurosis (PA) 240 (62.8%) was the most common diagnosis. This was followed by injuries to the hip in 81 (21.2%) and adductors in 56 (14.7%) cases. The adductor squeeze test (90° hip flexion) was sensitive (85.4%) but not specific for the pubic aponeurosis and adductor pathology (negative likelihood ratio 1.95). Analysed in series, positive MRI findings and tenderness of the pubic aponeurosis had a 92.8% post-test probability.

Conclusions

In this largest cohort of patients with athletic groin pain combining clinical and MRI diagnostics there was a 63% prevalence of PA injury. The adductor squeeze test was sensitive for athletic groin pain, but not specific individual pathologies. MRI improved diagnostic post-test probability. No hernia or incipient hernia was diagnosed.

Clinical trial registration number

Keywords: Groin, Overuse, Football, Epidemiology, MRI

Introduction

The groin is classically described as the inguinal region (L. inguen) at the junction of the abdomen and thigh.1 In an athletic population, chronic pain and injury in this area commonly presents in multidirectional sports including soccer,2 Australian rules football,3 gaelic football,4 ice hockey5 and rugby union.6 7 Recent work in football reports an incidence of up to 2.1/1000 h of play for groin injury.8

A systematic review9 reported 33 different terminologies in 72 studies including ‘osteitis pubis’10 in Australia; to ‘Gilmores’ groin in the UK;11 ‘sportsman's hernia’ in Europe;12 13 and ‘slap shot gut’ in North America.14 A recent surgical consensus group agreed on the descriptor ‘inguinal disruption’, while agreeing a visible or palpable disruption may not be obvious at presentation.15 These diagnoses are of purportedly injured anatomical structures and surgical approaches may be broadly grouped into tensioning,11 16 17 detensioning18–21 of the soft tissues of the inguinal region and in some patients hip arthroscopy.22 23 In the past decade, there has been increasing recognition that hip morphological changes can contribute to athletic groin pain.24 Whether this justifies a 365% increase in hip arthroscopy among 20–39-year-olds in the USA23 is questionable. This focus on early default to surgical intervention may be due to the perception of faster return to play over rehabilitation.25 Recent evidence25a contradicts this, a clearer description of the conservative management is therefore timely. Weir26 characterised pain in the groin area in an athletic population as ‘the field of athletic groin injuries’, similarly we employ the umbrella term ‘athletic groin pain’.

The four main cross-sectional studies in this area vary considerably in presenting diagnosis. Renström and Peterson27 described primarily adductor and rectus abdominis pathology. Lovell et al diagnosed incipient hernia in 50% of cases, while, Hölmich28 diagnosed adductor longus-related pathology in 58% of cases and sports hernia-related in 1.4%. Bradshaw et al29 reported pathology of the hip in 46% of cases, osteitis pubis in 22%. None of these studies had a complete series of prospectively-gathered standardised clinical examination, MRI and patient-reported outcome measures (PROM).

Different sporting cohorts or geographical populations may explain this variance in diagnosis, but it is more likely to represent the interpretation of clinical examination. These variations do not appear to have been accompanied by a corresponding change in management.30 31

In 2009, we published a means of simplifying the anatomical diagnostic process based on simple clinical algorithms used in clinical practice32 (figure 1). Our experience is that specific MRI protocols33 have played a role in the clinical differentiation process. Ultrasound examination of the groin is only partially effective; it facilitates a dynamic examination of the soft tissue structures of the groin; it is non-diagnostic for joint pathology or bone marrow oedema (BMO).34

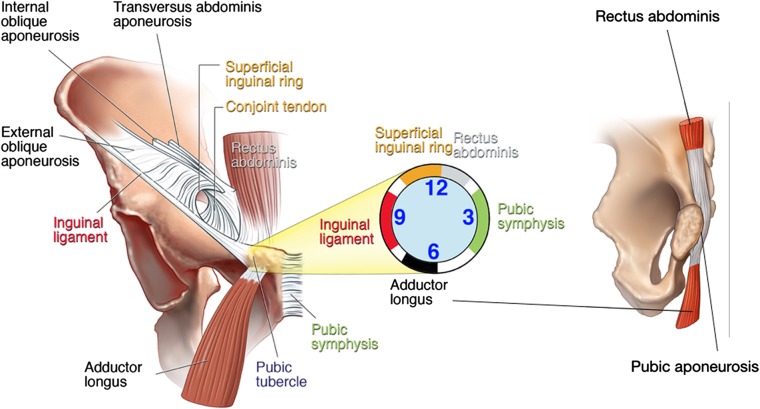

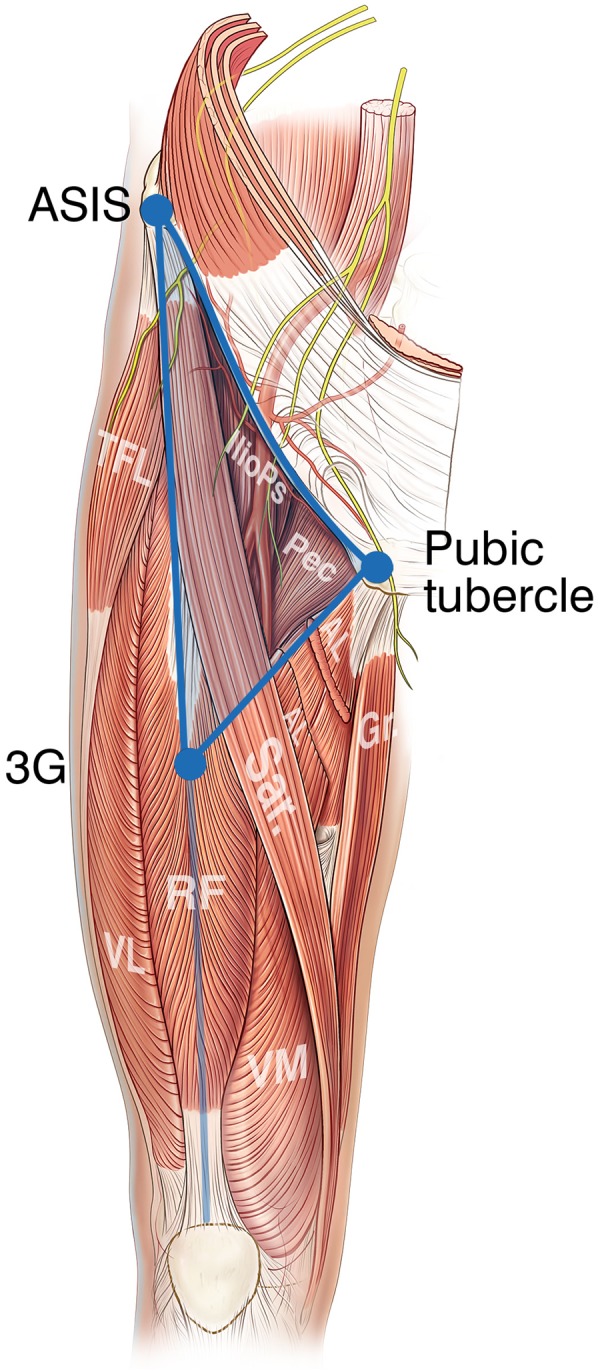

Figure 1.

The groin triangle—ASIS, anterior superior iliac spine, 3G point—point midway between the ASIS and upper pole of patell. TFL, tensor fascia lata; Pec, pectinius; ilioPs, iliopsoas; AL, adductor longus; Gr, gracilis; Sar, sartorius; RF, rectus femoris; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastus intermedius.

Patient function and the impact of injury on physical function are important factors to assess outcome. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS)35 36 is a validated tool which reflects these issues. This study included a PROM as part of initial assessment and ongoing monitoring throughout the rehabilitation process.

We aimed to describe clinical presentation, physical examination, MRI findings and PROM for a consecutive group of athletes presenting to a secondary and tertiary referral clinic with athletic groin pain.

Methods

Clinical examination was completed by two consultant sports physicians and senior physiotherapist and followed an agreed standardised format,37 based on prior publication.32 The patient undressed to underwear and hip joint range of motion (flexion, internal and external rotation) was assessed. Hip provocation tests, flexion adduction internal rotation38 (FADIR) and flexion abduction external rotation38 (FABER), were performed. Adductor squeeze tests (bilateral resisted adduction)39 at 90°, 45° and 0° hip flexion were performed (abbreviated as SQ90°, SQ45° and SQ0°). The crossover test40 and squeeze test39 were used to measure pain provocation and load tolerance through the pelvic ring. Prone internal and external rotation of the hip, Gaenslen's test41 and hip extension were performed. Slump test,42 femoral slump test,43 Thomas and Modified Thomas tests38 were performed. Palpation of the adductor insertion to tubercle, pubic symphysis and superficial and deep inguinal ring scrotal invagination were performed.

A consultant sports physician read all MRI scans at initial consultation and recorded structural pathology, a consultant radiologist subsequently reported all scans, the contents of which were recorded for this study. In particular abnormalities of the adductor origin, pubic aponeurosis, pubic bone, iliopsoas muscle or hip joints were recorded. Pubic BMO was recorded as a sign rather than a diagnosis.

All patients completed informed consent and the Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score (HAGOS),35 a validated PROM—at presentation. The Sports Surgery Clinic Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study (REF 25EF011).

Clinical diagnostic groupings

A clinical diagnosis was the product of directed history, clinical examination and MRI findings. This process is outlined in previous work by Falvey et al.32

PA injury

History of insidious onset pain superior and medial to the groin triangle (figure 1). Tenderness (ie, pain with palpation) of the rectus abdominis insertion to the superomedial aspect of the pubic bone (figure 2). Pain (at the pubic insertion of rectus abdominis) on squeeze test, positive crossover test, pain on resisted lower abdominal muscle contraction. MRI scan findings of high signal of, microtearing of,33 or separation of the PA from the pubic bone (figure 3).33

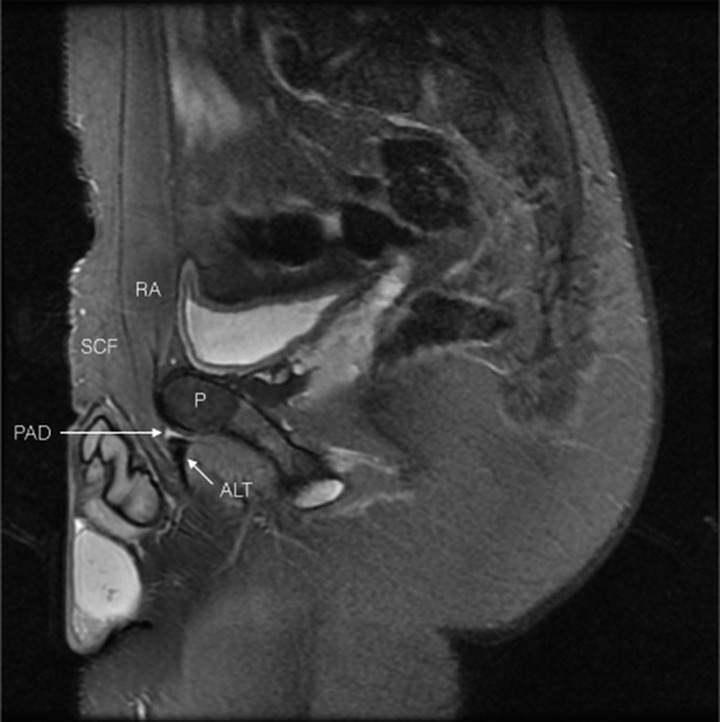

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the groin and pubic aponeurosis.

Figure 3.

Fat suppressed sagittal view of the groin. SCF, subcutaneous fat; RA, rectus abdominis; P, pubic bone; ALT, adductor longus tendon; PAD, pubic aponeurosis defect.

Adductor injury

History of insidious onset pain medial (but not superior) to the groin triangle (figure 1). Tenderness at the adductor origin from the inferior aspect of the pubic bone (figure 2). Pain (at the adductor origin) on squeeze test, pain noted on passive abduction of hip. MRI scan findings of high signal at, microtearing of or separation of the adductor from the pubic bone.44

Hip injury

History of pain within or lateral to the groin triangle (figure 1). Limited internal rotation of the hip (<30° with hip flexed to 90°), pain on FABER and/or FADIR.40 MRI scan findings consistent with hip pathology—femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI), osteochondral/chondrolabral pathology.45

Hip flexor injury

History of pain within the groin triangle32 (figure 1), insidious onset, worsened on rising from seated position. Pain within the groin triangle on Thomas test and on resisted hip flexor passive stretch. Tenderness over the iliopsoas belly,46 within the groin triangle.32

Inguinal injury

Diagnosis of exclusion where clinical and imaging findings above are not present. Resolution of presenting symptoms on local anaesthetic infiltration of ilioinguinal nerve.47

Data were collected on sport played and level of competition. Level was grouped into ‘recreational’ for non-organised physical activity, ‘club’ for organised competition or practice, ‘elite’ for representative, international and professional sport.

Statistical analysis

Distributions were summarised using means (SDs) or medians (intraquartile ranges) as appropriate. Proportions were compared using χ2 tests. Univariate associations of (1) squeeze test and (2) presence of pubic BMO on MRI with a diagnosis of PA injury were examined using logistic regression analysis. The presence, strength, independence and significance of these tests with a clinical diagnosis of PA injury was further quantified using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.20, (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA), using a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05. Two-by-two tables were created with the clinical diagnosis or imaging finding as the true positive/negative condition and the results of the clinical tests or imaging finding representing the diagnostic test being evaluated. Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios (LR) were calculated from these tables separately. Interpretation of likelihood ratios of disease for investigations was as follows; −LR <0.2 is moderate decrease in the likelihood and +LR >8 a moderate increase in the likelihood. A +LR <1.0 and a −LR >1.0 are of very limited clinical value.48

Results

Demographics

A total of 382 consecutive patients with athletic groin pain for a median time of (IQR) 36 (16–75) weeks presented for investigation and rehabilitation at Sports Surgery Clinic, Dublin, Ireland (mean±SD: age, 24.6±5.1 years; height, 181.1±5.4 cm; mass, 81.9±9.1 kg;). The majority listed gaelic football (57.9%) as their primary sport, followed by soccer (13.6%), hurling (10.5%) and finally rugby (8.6%; table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical findings

| Category | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 27.6 (7.6) | |

| Height (cm) (mean, SD) | 180 (6.0) | |

| Weight (kg) (mean, SD) | 81.9 (9.4) | |

| Duration of symptoms in weeks- (median, IQR, range) | 36 (16–75), (8–520) | |

| Sport | (%) | Individual diagnosis |

| Gaelic Football | 57.9 | PA (59%), Add (15%), Hip (22%), HF (3%), Ing (1%) |

| Hurling | 10.5 | PA (53%), Add (15%), Hip (27%), HF (3%), Ing (2%) |

| Soccer | 13.6 | PA (77%), Add (12%), Hip (11%), HF (0%), Ing (0%) |

| Rugby | 8.6 | PA (67%), Add (12%), Hip (21%), HF (0), Ing (0) |

| Athletics | 6.3 | PA (54%), Add (13%), Hip (25%), HF (4%), Ing (4%) |

| Other | 3.1 | PA (58%), Add (25%), Hip (17%), HF (0), Ing (0) |

| Level of participation | (%) | |

| Elite | 25.7 | PA (61%), Add (15%), Hip (21%), HF (2%), Ing (1%) |

| Club | 65.2 | PA (58%), Add (16%), Hip (21%), HF (4%), Ing (1%) |

| Recreational | 9.2 | PA (62%), Add (9%), Hip (26%), HF (0), Ing (3%) |

Add, adductor injury; HF, hip flexor injury; Hip, hip injury; Ing, inguinal injury; Other, golf, ju-jitsu, rowing, hockey.

Clinical examination

Pain on presentation was localised primarily to the left in 163 (42.7%) cases, to the right in 146 (38.2%) cases, and bilateral in 73 (19.1%) cases. Tenderness of the adductor origin was noted in 225 (58.9%) cases, (right-sided; n=139 (36.4%), left-sided; n=144 (37.7%). The PA was tender in 256 (67%) cases (right-sided; n=150 (39.3%), left-sided; n=166 (43.5%)). Palpation of the superficial inguinal ring and deep inguinal ring provoked the patient's presenting pain in 10 (2.6%) and 2 (0.5%) cases, respectively. Hip internal rotation was limited (<30°) on the left side in 287 (75.1%) cases and on the right side in 305 (79.8%) cases. Reduced hip rotation on either or both sides was seen in 328 (85.9%) cases.

Pain was reported in the adductor squeeze test at 90° (SQ90°) in 314 (82.2%) cases; in 290 (75.9%) cases on SQ45° and in 310 (81.2%) on SQ0°. The crossover test was painful in 159 (41.6%) cases.

MRI findings

Pubic BMO was present on MRI in 259 (67.8%) cases. Oedema was bilateral in 151 (39.5%); unilateral left-sided in 58 (15.2%); unilateral right-sided in 50 (13.1%). Abnormal adductor imaging findings were seen in 145 (38%) cases—right side 51 (13.4%), left side 67 (17.5%), bilateral 27 (7.1%). Abnormal PA imaging findings were seen in 201 (52.6%) cases—right side 90 (23.5%), left side 111 (22%), bilateral 27 (7.1%). Abnormal hip imaging findings were seen in 170 (44.5%) cases—right side 43 (11.3%), left side 41 (10.7%), bilateral 86 (22.5%). Twenty-seven (7.1%) patients had ‘normal’ MRI scans (no abnormal findings). More than a third (n=131, 34.3%) had 2 abnormal findings, and 112 (29.3%) patients had 3 or more abnormal findings on MRI.

Clinical diagnosis

A primary clinical diagnosis of PA injury was made in 240 (62.8%) cases, hip injury was diagnosed in 81 (21.2%) cases these overlapped in 8 (2.1%) cases. Ten patients (2.6%) were referred for arthroscopic hip evaluation. Adductor injury was diagnosed in 56 (14.7%) cases, iliopsoas injury in 10 (2.6%) and inguinal injury in 3 (0.8%) cases (all related to the ilioinguinal nerve). The 10 overlapping patients were deemed primarily PA injury secondary to an underlying hip issue.

Clinical test association with diagnostic category

The adductor SQ was closely associated with tenderness of the adductor origin; Pearsons χ2 SQ90°, p<0.001; SQ45°, p<0.001; SQ0°, p=0.002. The adductor SQ was also associated with tenderness of the PA; SQ90°, p=0.004; SQ45°, p=0.174; SQ0°, p<0.0001. There was no association between the adductor SQ and a physician diagnosis of adductor injury; SQ90°, p=0.15; SQ45°, p=0.428; SQ0°, p=0.890. PA injury was strongly associated with adductor SQ at 0° (SQ0°, p<0.0001), less so at 90° (SQ90°, p=0.033) and 45° (SQ45°, p=0.029). The relationship of PA diagnosis and a positive adductor SQ at 0° persisted when we used logistic regression analysis (univariate) and it remained significant following adjustment for tenderness of the adductor origin, BMO on MRI, sporting activity, level of participation and duration of symptoms (table 2).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted OR for association of diagnosis pubic aponeurosis injury and positive squeeze test at 0° hip extension (SQ0°)

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 2.9 | 1.7 to 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 2.8 | 1.6 to 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 2.6 | 1.5 to 4.5 | 0.001 |

| Model 4 | 2.5 | 1.5 to 4.4 | 0.001 |

| Model 5 | 2.7 | 1.4 to 4.9 | 0.002 |

Model 1: unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for pain on palpation of adductor origin (bilateral).

Model 3: adjusted for pain on palpation of adductor origin (bilateral) and BMO.

Model 4: adjusted for pain on palpation of adductor origin (bilateral), BMO, sporting activity and level of participation.

Model 5: adjusted for pain on palpation of adductor origin (bilateral), BMO, sporting activity and level of participation and duration of groin pain (weeks).

BMO, bone marrow oedema.

MRI findings, associations with clinical signs

The presence of pubic BMO was closely related to site of pain (p<0.001). In particular the positive predictive value for left-sided BMO in a patient with left-sided pain was 86.21% (CI 74.62% to 93.85%) and for right-sided BMO in a patient with right-sided pain was 92% (CI 80.77% to 97.78%) while the negative predictive value of bilateral BMO in a patient with bilateral pain was 79.22% (CI 74.45% to 83.45%). The presence of BMO was closely associated with a diagnosis of PA injury on univariate logistic regression analysis (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.5 to 3.8, p<0.001). This relationship persisted on multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for tenderness of the PA, SQ90°, SQ45° and SQ0°, sporting activity and level of participation but was attenuated on addition of duration of symptoms (table 3). The presence of BMO was also closely associated with a diagnosis of pathology of the adductor origin (OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.7 to 8.7, p=0.001). Tenderness of the PA (OR 3.2, 95% CI 2.1 to 5.1, p<0.001) and adductor origin (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.5 to 3.6, p<0.001) was closely associated with the positive imaging findings for the presence of BMO.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted OR for association of diagnosis pubic aponeurosis and bilateral bone marrow oedema

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 2.4 | 1.5 to 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 2.4 | 1.4 to 4.2 | 0.002 |

| Model 3 | 2.4 | 1.4 to 4.2 | 0.002 |

| Model 4 | 2.4 | 1.4 to 4.1 | 0.002 |

| Model 5 | 2.0 | 1.3 to 3.3 | 0.004 |

| Model 6 | 2.1 | 1.2 to 3.7 | 0.007 |

Model 1: unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for palpation aponeurosis (either side).

Model 3: adjusted for palpation aponeurosis (either side) and SQ90.

Model 4: adjusted for palpation aponeurosis (either side), SQ90 and SQ45.

Model 5: adjusted for palpation aponeurosis (either side), SQ90, SQ45 sporting activity and level of participation.

Model 6: adjusted for palpation aponeurosis (either side), SQ90, SQ45 sporting activity and level of participation and duration of groin pain (weeks).

SQ, squeeze test.

The presence of BMO was not associated with confirmed hip pathology on MRI scan (p=0.172), or limitation in hip range of motion on clinical examination (p=0.513). There was no association seen between confirmed hip pathology on MRI and limitation of internal rotation of the hip on examination, either when sides were compared (left-sided imaging findings and left-sided examination findings) or when grouped into limited hip range of motion and presence of hip pathology on scan; left side—p=0.233; right side—p=0.177; grouped—p=0.539.

Clinical utility of examination and investigations

Clinical tests such as the adductor SQ tended to be sensitive however the negative likelihood ratio of 1.95 indicates that this is a very poor test to exclude pathology of the PA (table 4). The negative likelihood ratio for palpation of the PA of 0.22 is the most accurate way to exclude PA pathology. No tenderness is the best to rule PA injury out. The adductor SQ at all ranges were poor tests for adductor and PA pathology (table 4). Again a strong negative likelihood ratio is seen for palpation of the adductor origin at 0.11—indicating that pain-free direct palpation of the adductor origin is the most accurate clinical test to exclude adductor pathology.

Table 4.

Clinical tests used to diagnose pubic aponeurosis, adductor and hip pathology

| Diagnosis | Test | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA injury | SQ90° | 85.4 | 7.5 | 65.3 | 48.5 | 0.92 | 1.95 |

| SQ45° | 79.5 | 30.3 | 65.9 | 46.7 | 1.14 | 0.68 | |

| SQ0° | 87.5 | 29.6 | 67.7 | 58.3 | 1.24 | 0.42 | |

| Palp PA | 85.3 | 68.1 | 85.4 | 77.4 | 2.67 | 0.22 | |

| Palp adductor | 62.1 | 46.5 | 66.2 | 42 | 1.16 | 0.82 | |

| Hip IR limited | 86.6 | 15.3 | 63.4 | 40.7 | 1.02 | 0.88 | |

| Cross-over +ve | 45 | 64.1 | 67.9 | 40.8 | 1.25 | 0.86 | |

| Adductor injury | SQ90° | 89.3 | 18.6 | 16 | 90.9 | 1.1 | 0.58 |

| SQ45° | 80.4 | 24.5 | 15.6 | 87.8 | 1.07 | 0.8 | |

| SQ0° | 82.1 | 18.6 | 14.9 | 85.7 | 1.01 | 0.96 | |

| Palp adductor | 94.6 | 47.5 | 23.9 | 98.1 | 1.8 | 0.11 | |

| Palp PA | 53.6 | 30.2 | 12.2 | 78.9 | 0.77 | 1.54 | |

| Hip IR limited | 82.1 | 13.4 | 14.2 | 81.1 | 0.95 | 1.34 | |

| Cross-over +ve | 41.1 | 58.4 | 14.6 | 85.1 | 0.99 | 1.01 | |

| Hip injury | SQ90° | 67.2 | 18.8 | 15 | 72.8 | 0.83 | 1.74 |

| SQ45° | 65.4 | 21.0 | 18.3 | 69.2 | 0.83 | 1.64 | |

| SQ0° | 71.6 | 16.0 | 18.7 | 67.6 | 0.85 | 1.78 | |

| Hip IR limited | 90.1 | 15.3 | 14.1 | 85.2 | 1.06 | 0.65 | |

| Cross-over +ve | 34.6 | 56.7 | 17.7 | 76.2 | 0.80 | 1.15 |

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for tests shown.

Cross-over +ve, pain on cross-over test; L, left side; NPV, negative predictive value; PA, pubic aponeurosis, Hip IR limited, limited hip internal rotation; Palp adductor, palpatory tenderness of the adductor origin; Palp PA, palpatory tenderness of the pubic aponeurosis; PPV, positive predictive value; R, right side; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; SQ0°, adductor squeeze test at 0° hip flexion; SQ45°, adductor squeeze test at 45° hip flexion; SQ90°, adductor squeeze test at 90° hip flexion.

Following MRI scan there was a moderate increase in the likelihood of PA and a small increase in the likelihood of adductor injury (table 5).

Table 5.

MRI findings seen at examination

| Diagnosis | MRI finding | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA injury | Bilateral BMO | 47.3 | 73.0 | 74.8 | 45.0 | 1.75 | 0.35 |

| BMO present | 75.7 | 44.7 | 69.9 | 52.0 | 1.36 | 0.54 | |

| MRI PA injury | 75.3 | 85.7 | 89.6 | 67.0 | 5.27 | 0.29 | |

| MRI adductor injury | 38.4 | 68.1 | 62.8 | 37.0 | 1.0 | 0.99 | |

| Hip pathology | 31.4 | 32.6 | 44.1 | 21.9 | 0.47 | 2.10 | |

| Adductor injury | Bilateral BMO | 41.1 | 60.7 | 15.4 | 85.5 | 1.05 | 0.32 |

| BMO present | 87.5 | 35.2 | 19.1 | 94.2 | 1.35 | 0.36 | |

| MRI PA injury | 25.0 | 42.0 | 7.0 | 76.3 | 0.43 | 1.78 | |

| MRI adductor injury | 85.7 | 70.1 | 33.3 | 96.6 | 2.86 | 0.20 | |

| Hip pathology | 35.7 | 53.4 | 11.9 | 82.9 | 0.77 | 1.20 | |

| Hip injury | Bilateral BMO | 23.5 | 55.9 | 12.6 | 72.9 | 0.53 | 1.36 |

| BMO present | 40.7 | 24.4 | 12.7 | 60.3 | 0.54 | 2.43 | |

| MRI PA injury | 12.3 | 36.1 | 4.98 | 60.3 | 0.19 | 0.66 | |

| MRI adductor injury | 75.3 | 85.7 | 8.28 | 70.6 | 0.33 | 1.54 | |

| MRI hip pathology | 96.3 | 69.2 | 45.9 | 98.6 | 3.13 | 0.05 |

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for tests shown.

BMO, pubic bone marrow oedema; L, left side; NPV, negative predictive value; PA, pubic aponeurosis; PPV, positive predictive value; R, right side; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; SQ0°, adductor squeeze test at 0° hip flexion; SQ45°, adductor squeeze test at 45° hip flexion; SQ90°, adductor squeeze test at 90° hip flexion.

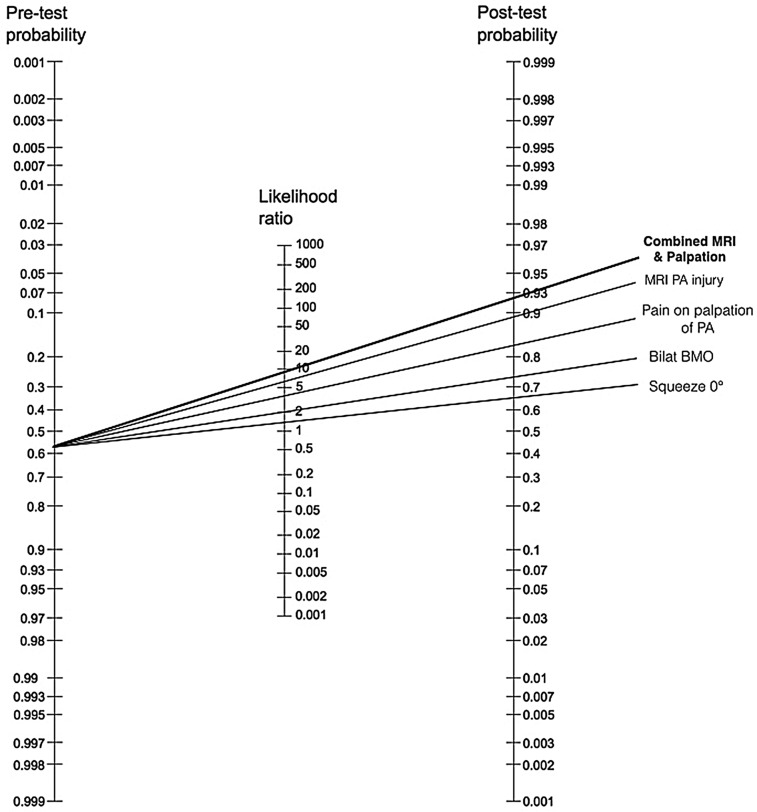

The pretest and post-test odds for tests used to investigate PA and adductor injury are described in table 6. When the clinical and radiological tests were conducted in series the post-test odds of PA injury increased to 7.78 (table 6), these findings are demonstrated for PA injury in the Fagan nomogram (figure 4).

Table 6.

Most discriminative tests in combination

| Diagnosis | Investigation | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | Preprob | Postprob | Preodds | Postodds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA injury | Bilateral BMO | 47.3 | 73.0 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 1.67 | 2.92 |

| MRI PA injury | 75.3 | 85.7 | 0.63 | 0.89 | 1.67 | 8.80 | |

| SQ0° | 87.5 | 29.6 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 1.67 | 2.07 | |

| Palp PA | 85.3 | 68.1 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 1.67 | 4.46 | |

| Tests conducted in series | Palp PA and MRI PA | 64.2 | 95.4 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 1.67 | 7.78 |

| Adductor injury | BMO present | 87.5 | 35.2 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| MRI adductor injury | 85.7 | 70.1 | 0.15 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.49 | |

| SQ90° | 89.3 | 18.6 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.19 | |

| Palp Add | 94.6 | 47.5 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.31 | |

| Tests conducted in series | Palp Add and MRI Add | 81.1 | 84.3 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 1.67 | 0.89 |

Sensitivity, specificity, pretest probability, pretest odds, post-test probability and post-test odds for the most useful diagnostic tests for pubic aponeurosis and adductor injury.

BMO, pubic bone marrow oedema; L, left side; PA, pubic aponeurosis; R, right side; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; SQ0°, adductor squeeze test at 0° hip flexion; SQ90°, adductor squeeze test at 90° hip flexion.

Figure 4.

Fagan nomogram showing pretest and post-test probability and likelihood ratios of tests for pubic aponeurosis injury. BMO, pubic bone marrow oedema; MRI; PA, pubic aponeurosis; SQ0°, adductor squeeze test at 0°.

Patient-reported outcome scores

Median HAGOS scores at presentation are shown in table 7. Median HAGOS scores of 35 (IQR 25–50) for athletic function and 50 (IQR 37.5–65) for function in sport and recreation demonstrate the impact of athletic groin pain on athletic function.

Table 7.

HAGOS findings

| HAGOS | Median | Interquartile range |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | 72.5 | 60–85 |

| Symptoms | 64 | 50–71.5 |

| Sport/rec | 50 | 37.5–65 |

| PA | 75 | 12.5–100 |

| QoL | 35 | 25–50 |

| ADL | 80 | 60–90 |

ADL, activities in daily living; HAGOS, hip and groin outcome score; PA, participation in physical activities; QoL, hip and/or groin-related Quality of Life; Sports/rec, function in sport and recreation.

Discussion

This is the largest prospective cohort of patients with athletic groin pain in the literature to date, and the first to directly combine clinical and MRI findings in making a diagnosis. The cohort demographics are similar, including HAGOS scores, to previously published data.28 29 49

The most common clinical diagnosis was pain arising the PA injury.33 This diagnosis is described, it has not been a common diagnosis in the existing literature.27–29 50 Previous studies describing adductor pathology did so in the absence of MRI findings, focusing on clinical examination alone; localised adductor tenderness, pain with the adductor squeeze test and painful passive abduction.28 30 51 We highlight the poor post-test probability of the adductor SQ. We contend that rather than a new diagnosis, our diagnosis of PA injury represents the anatomical presentation seen in many previous studies but is delineated appropriately with the advent in particular of sagittal MRI.

Clinical tests classically utilised in the examination of the painful groin such as the adductor SQ39 are unable exclude pathology of the PA or adductor. Absent tenderness at the PA and adductor insertion are specific tests with a negative likelihood ratio of 0.22 and 0.11 respectively.

Contribution of MRI to accurate diagnosis of patients with chronic athletic groin pain

The use of MRI in ‘adductor related groin pain’52 53 and groin injury,53 has been challenged due to a risk of misinterpretation of chronic imaging changes in an acute setting. We believe our study supports the role of MRI as part of the diagnostic workup. Not only of inguinal pathology but also inflammatory change in hip joint, sacrum, ilium and proximal femora, pelvic tendon attachments and pelvic musculature.33 54 55 In our approach to diagnosis, MRI combined with clinical tests (MRI finding of PA injury and tenderness of the PA) increases the probability of the diagnosis from a pretest probability of 62–93%, highly favourable when compared to clinical findings alone (table 6, figure 4).

The majority of non-surgical literature in athletic groin pain has focused on the role of the adductor muscles.28 30 31 39 51 56–58 Pain in the lower abdominal area, frequently occurs in combination with pain in the adductor. If the diagnosis is made clinically using tenderness of the pubic area and pain on resisted adduction, this presentation is likely to be labelled adductor pain.39 The anatomy of the PA33 is such the rectus abdominis insertion is in direct continuation with the adductor origin. We argue that this means the traditional dogma for diagnosing adductor pain has the potential to miss PA injury. Thus a patient with combined lower abdominal and adductor pain may be suffering from pathology in the PA area (figure 2).

Recent work52 53 has highlighted that pubic BMO and adductor changes were common on MRI scan, in symptomatic and asymptomatic soccer players. We would agree that ‘BMO may reflect a sports-specific stress reaction in the pubic bones’.52 perhaps indicating that BMO may lie on a spectrum from normal to excessive training load. Our data supports that MRI findings of BMO, adductor and PA pathology had poor sensitivity but were specific for site of pain in athletic groin pain.

Adductor SQ: does it have limitations?

We found a strong relationship between the adductor SQ0°, the clinical signs of tenderness of the adductor origin and an MRI finding of BMO. There was no relationship between physician diagnosis of adductor pathology and the adductor SQ. We argue that pain reproduced during the adductor SQ represents a degree of distress across the anterior pubic area, both soft tissue (adductor, rectus abdominis and obliques) and bone (pubic bone and symphysis). We dispute the dogma that the test is specific for adductor pathology. Our data indicate that the adductor SQ is sensitive for athletic groin pain, but not specific for adductor, rectus abdominis or iliopsoas pathology. Thus we argue the adductor SQ is unlikely to be diagnostic in the manner it has been argued to date. Through its various insertions into the pubic tubercle, pubic symphysis, PA and the conjoint tendon, the adductor exerts multiple force vectors across the anterior groin and difficult to isolate clinically.

This has significant implications for rehabilitation protocols used in athletic groin pain. Many utilise static or isometric contractions of the adductor to strengthen apparent adductor muscle strength deficits.30 31 51 Many patients in this study diagnosed with rectus abdominis and hip flexor injury had a painful weakened SQ. We did not measure adductor squeeze strengths with handheld dynamometry or sphygmomanometery and thus cannot comment on deficits in this metric. Where pain inhibition of the adductor muscle rather than primary weakness is the cause of a positive SQ—rehabilitation measures, guided by adductor signs alone and subsequent adductor strengthening programmes may be misdirected. This may serve to significantly lengthen the rehabilitation process.

Hip pathology, inguinal pathology

MRI revealed abnormal signal within the hip in 170 patients (bilateral in 86 cases) this was deemed the cause of the patient's pain in less than half of these cases (n=81, 21.2% of total cases). Only 10 of these cases (2.6%) were referred for arthroscopic surgery. This is concordant with high rates of asymptomatic hip imaging changes seen in collegiate athletes,59 and high incidences of hip morphological changes in patients presenting with adductor-related athletic groin pain.58

The superficial and deep inguinal rings were palpated in all patients via invagination of the scrotum. The correlation of physical examination and MRI has a specificity of 94.5% and specificity of 96.3% in the diagnosis of inguinal hernia.60 Inguinal canal pathology was not diagnosed. Multiple abnormalities were however identified on MRI scan in nearly two-thirds of patients (n=243, 63.6%).

Limitations

There are some limitations in this work.

The MRI protocol used in this study did not include axial oblique images of the femoral head/neck. Sequences used were primarily directed toward soft tissue pathology in the anterior groin. Further imaging of the hip, where clinically relevant, was performed.

The examination performed was standardised and based on published literature in the area. Both examining physicians have published on the most evidence-based means of examining the groin. Where possible validated tests with inter-tester reliability were used, inter-tester reliability was not assessed for the standardised examination.

Control groups for comparison of both clinical and radiological findings were not included in this work, this raises the possibility that chronic yet asymptomatic MRI findings may have been included.52

Conclusion

In this largest cohort of patients with athletic groin pain combining clinical and MRI diagnostics—we made the diagnosis of PA injury in 63% of the series. This diagnosis should be considered more often by clinicians working in this area—failure to do so underestimates the role of lower abdominal musculature in the genesis of athletic groin pain.

The adductor SQ was sensitive for athletic groin pain, but not specific for adductor, PA or iliopsoas pathology. The specificity and post-test probability of diagnosis were improved by combination of clinical (palpation) and radiological findings in series.

The improved post-test diagnostic probabilities seen following the incorporation of MRI in the diagnostic process highlights the benefits of immediate correlation between clinical examination and MRI by the sports physician. Surgery for presumed inguinal pathology dominates the literature yet we failed to identify a hernia, clinically or radiologically, despite MRI findings of a variety of concomitant abnormalities in any subject. Nearly two-thirds of patients (63.6%) demonstrated pain and abnormality in multiple anatomical structures. This implies that at any point in time a number of structures may be ‘pathological’ resulting in pain. As a result we argue that focusing on injury mechanism may be more productive rather than attempting to isolate individual pathological structures. If our approach proves correct, addressing biomechanical abnormalities will prove a novel treatment approach.

What are the findings?

The most common diagnosis was that of pubic aponeurosis injury.

MRIs commonly revealed several areas of abnormal signal,—raising the possibility of several sources of pain in the one patient.

A combination of clinical findings and MRI improved post-test diagnostic probability.

Despite the prevalence of abnormal hip signal on MRI, relatively few patients met the criteria for surgical intervention.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the future?

Future work should be directed at understanding the underpinning biomechanical loads in change of direction and the development of femoroacetabular impingement and pubic bone oedema.

Reliance on clinical tests alone to make the diagnosis has the potential for inaccuracy and MRI support may improve diagnostic likelihood ratios.

This paper outlines an integrated physical examination and radiological review for accurate diagnosis of athletic groin pain. It highlights the presentation of multiple concurrent pathologies (a combined clinical radiological diagnosis) and lack of sensitivity of individual physical diagnostic tests.

Diagnostic and rehabilitation strategies aimed at and designed toward treating single pathological anatomical entities are likely to be limited.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of the patients who participated in this study. The authors wish to acknowledge the efforts of all of the staff of Sports Surgery Clinic in particular Eamon O'Reilly and Jenny Ward.

Footnotes

Twitter: New Research: Clinical examination alone in Athletic Groin pain under diagnoses anatomical pathology in abscence of MRI @BJSM_BMJ@SSCSantry

Contributors: EF, EK and AF-M examined patients, gathered data, analysed data, prepared and reviewed the manuscript. SK performed statistical analysis and aided in preparation and review of manuscript.

Funding: This clinical study was funded by the Sports Surgery Clinic, Dublin.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Sport Surgery Clinic Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study (REF 25EF011).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Moore KL. The lower limb. In: Satterfield TS, ed. Clinically oriented anatomy. Williams & Wilkins, 1992:373–497. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walden M, Hagglund M, Ekstrand J. Football injuries during European Championships 2004–2005. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Sep;15(9):1155–62. Epub 2007 Mar 21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Fon GT. Incidence of pubic bone marrow oedema in Australian rules football players: relation to groin pain. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:28–33. 10.1136/bjsm.35.1.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy JC, O'Malley E, Gissane C, et al. Incidence of injury in Gaelic football: a 4-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2113–20. 10.1177/0363546512455315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH, Powell JW. Groin and abdominal strain injuries in the National Hockey League. Clin J Sport Med 1999;9:151–6. 10.1097/00042752-199907000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, et al. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: part 1 match injuries. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:757–66. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks J, Fuller C, Kemp S, et al. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: part 2 training Injuries. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:767–75. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldén M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J. The epidemiology of groin injury in senior football: a systematic review of prospective studies. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:792–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serner A, van Eijck CH, Beumer BR, et al. Study quality on groin injury management remains low: a systematic review on treatment of groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:813 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verrall GM, Hamilton IA, Slavotinek JP, et al. Hip joint range of motion reduction in sports-related chronic groin injury diagnosed as pubic bone stress injury. J Sci Med Sport 2005;8:77–84. 10.1016/S1440-2440(05)80027-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmore J. Groin pain in the soccer athlete: fact, fiction, and treatment. Clin Sports Med 1998;17:787–93, vii 10.1016/S0278-5919(05)70119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziprin P, Prabhudesai SG, Abrahams S, et al. Transabdominal preperitoneal laparoscopic approach for the treatment of sportsman's hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2008;18:669–72. 10.1089/lap.2007.0130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moeller JL. Sportsman's hernia. Curr Sports Med Rep 2007;6:111–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RA, Mascia A, Kinnear DG, et al. An 18-year review of sports groin injuries in the elite hockey player: clinical presentation, new diagnostic imaging, treatment, and results. Clin J Sport Med 2008;18:221–6. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318172831a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheen AJ, Stephenson BM, Lloyd DM, et al. ‘Treatment of the sportsman's groin’: British Hernia Society's 2014 position statement based on the Manchester Consensus Conference. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1079–87. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muschaweck U, Berger LM. Sportsmen's groin-diagnostic approach and treatment with the minimal repair technique: a Single-Center Uncontrolled Clinical Review. Sports Health 2010;2:216–21. 10.1177/1941738110367623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brannigan AE, Kerin MJ, McEntee GP. Gilmore's groin repair in athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2000;30:329–32. 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.6.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lloyd DM, Sutton CD, Altafa A, et al. Laparoscopic inguinal ligament tenotomy and mesh reinforcement of the anterior abdominal wall: a new approach for the management of chronic groin pain. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2008;18:363–8. 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181761fcc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maffulli N, Loppini M, Longo UG, et al. Bilateral mini-invasive adductor tenotomy for the management of chronic unilateral adductor longus tendinopathy in athletes. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:1880–6. 10.1177/0363546512448364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann CD, Sutton CD, Garcea G, et al. The inguinal release procedure for groin pain: initial experience in 73 sportsmen/women. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:579–83. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.053132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyers WC, McKechnie A, Philippon MJ, et al. Experience with “sports hernia” spanning two decades. Ann Surg 2008;248:656–65. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187a770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozic KJ, Chan V, Valone FH III, et al. Trends in hip arthroscopy utilization in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2013;28(8 Suppl):140–3. 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hobson T, et al. Trends and demographics in hip arthroscopy in the United States. Arthroscopy 2013;29:661–5. 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiman MP, Thorborg K. Femoroacetabular impingement surgery: are we moving too fast and too far beyond the evidence? Br J Sports Med 2015;49:782–4. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jardi J, Rodas G, Pedret C, et al. Osteitis pubis: can early return to elite competition be contemplated? Transl Med UniSa 2014;10:52–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.King E, Ward J, Small L, Falvey E, et al. Athletic groin pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical versus physical therapy rehabilitation outcomes Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weir A. From disruption to consensus: the thousand mile journey. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1075–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renström P, Peterson L. Groin injuries in athletes. Br J Sports Med 1980;14:30–6. 10.1136/bjsm.14.1.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hölmich P. Long-standing groin pain in sportspeople falls into three primary patterns, a “clinical entity” approach: a prospective study of 207 patients. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:247–52; discussion 52 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradshaw CJ, Bundy M, Falvey E. The diagnosis of longstanding groin pain: a prospective clinical cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:851–4. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.039685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hölmich P, Uhrskou P, Ulnits L, et al. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:439–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03340-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weir A, Jansen JA, van de Port IG, et al. Manual or exercise therapy for long-standing adductor-related groin pain: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Man Ther 2011;16:148–54. 10.1016/j.math.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falvey EC, Franklyn-Miller A, McCrory PR. The groin triangle: a patho-anatomical approach to the diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:213–20. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.042259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zoga AC, Mullens FE, Meyers WC. The spectrum of MR imaging in athletic pubalgia. Radiol Clin North Am 2010;48:1179–97. 10.1016/j.rcl.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson P, Bhat V, English B. Imaging in the assessment and management of athletic pubalgia. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2011;15:14–26. 10.1055/s-0031-1271956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorborg K, Branci S, Stensbirk F, et al. Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score (HAGOS) in male soccer: reference values for hip and groin injury-free players. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:557–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorborg K, Hölmich P, Christensen R, et al. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:478–91. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.080937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SSC. Examination of the painful athletic groin. Secondary Examination of the painful athletic groin [Online resource] 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SudZH3FcwMo&feature=em-share_video_user

- 38.Malanga GA, Nadler SF. Physical examination of the hip. In: Malanga GA, ed. Musculoskeletal physical examination–an evidence-based approach. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby, 2006:251–78. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hölmich P, Hölmich LR, Bjerg AM. Clinical examination of athletes with groin pain: an intraobserver and interobserver reliability study. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:446–51. 10.1136/bjsm.2003.004754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brukner PB, Kahn K. Groin pain. Clinical sports medicine. 4th edn Syndey: McGraw-Hill, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaenslen FJ. Sacro-iliac arthrodesis. JAMA 1927;89:2031–5. 10.1001/jama.1927.02690240023008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cyriax J. Perineuritis. Br Med J 1942;1:578–80. 10.1136/bmj.1.4244.578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Estridge MN, Rouhe SA, Johnson NG. The femoral stretching test. A valuable sign in diagnosing upper lumbar disc herniations . J Neurosurg 1982;57:813–17. 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson P, Barron DA, Parsons W, et al. Adductor-related groin pain in athletes: correlation of MR imaging with clinical findings. Skeletal Radiol 2004;33:451–7. 10.1007/s00256-004-0753-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riley GM, McWalter EJ, Stevens KJ, et al. MRI of the hip for the evaluation of femoroacetabular impingement; past, present, and future. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41:558–72. 10.1002/jmri.24725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bui KL, Ilaslan H, Recht M, et al. Iliopsoas injury: an MRI study of patterns and prevalence correlated with clinical findings. Skeletal Radiol 2008;37:245–9. 10.1007/s00256-007-0414-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Comin J, Obaid H, Lammers G, et al. Radiofrequency denervation of the inguinal ligament for the treatment of ‘Sportsman's Hernia’: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:380–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Refining clinical diagnosis with likelihood ratios. Lancet 2005;365:1500–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66422-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sansone M, Ahldén M, Jonasson P, et al. Can hip impingement be mistaken for tendon pain in the groin? A long-term follow-up of tenotomy for groin pain in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:786–92. 10.1007/s00167-013-2738-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport 1995;27:76–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmich P, Dienst M. [Differential diagnosis of hip and groin pain. Symptoms and technique for physical examination]. Orthopade 2006;35:8, 10–5 10.1007/s00132-005-0888-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Branci S, Thorborg K, Bech BH, et al. MRI findings in soccer players with long-standing adductor-related groin pain and asymptomatic controls. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:681–91. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robinson P, Grainger AJ, Hensor EM, et al. Do MRI and ultrasound of the anterior pelvis correlate with, or predict, young football players’ clinical findings? A 4-year prospective study of elite academy soccer players. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:176–82. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ansede G, English B, Healy JC. Groin pain: clinical assessment and the role of MR imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2011;15:3–13. 10.1055/s-0031-1271955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palisch A, Zoga AC, Meyers WC. Imaging of athletic pubalgia and core muscle injuries: clinical and therapeutic correlations. Clin Sports Med 2013;32:427–47. 10.1016/j.csm.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delahunt E, McEntee BL, Kennelly C, et al. Intrarater reliability of the adductor squeeze test in Gaelic games athletes. J Athl Train 2011;46:241–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thorborg K, Serner A, Petersen J, et al. Hip adduction and abduction strength profiles in elite soccer players: implications for clinical evaluation of hip adductor muscle recovery after injury. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:121–6. 10.1177/0363546510378081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weir A, de Vos RJ, Moen M, et al. Prevalence of radiological signs of femoroacetabular impingement in patients presenting with long-standing adductor-related groin pain. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:6–9. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.060434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frank JM, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, et al. Prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement imaging findings in asymptomatic volunteers: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 2015;31:1199–204. 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van den Berg JC, de Valois JC, Go PM, et al. Detection of groin hernia with physical examination, ultrasound, and MRI compared with laparoscopic findings. Invest Radiol 1999;34:739–43. 10.1097/00004424-199912000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]