Abstract

The objective of this qualitative research study was to discover how creating mandalas (art made in reference to a circle) might provide medical students with an opportunity for reflection on their current psychological state. As part of their year 3 family medicine rotation, medical students participated in an art-making workshop, during which, they created mandalas based on their current emotional state. Afterwards, they engaged in reflective writing and discussion. The responses of 180 students were analysed and coded according to the mandala classification framework ‘Archetypal Stages of The Great Round of Mandala’. The results indicated that students were actively struggling in integrating conflicting perspectives as they were attempting to reconcile their professional identity as doctors. Additional results pertaining to psychosocial characteristics included navigating difficult emotions, requiring nurturance, handling endings, contemplating existential concerns and managing stress. The study has implications for making use of mandala making within a Jungian framework as means for medical students to reflect on their emotional state and achieve psychological balance.

Introduction

A growing trend in medical schools is the introduction of the medical humanities into a biomedically oriented medical curriculum. Among its aims, such initiatives seek to nurture the capacity of doctors to understand the psychosocial impact of disease and to gain increased perspective on pain and suffering as part of a holistic model of care. The curriculum also aims to help medical students enhance self-awareness for both self-care and in order to improve patient care,1 2 Through such training, it is hoped that doctors will achieve a better balance in their emotional, psychological and spiritual aspects. Building on our earlier work exploring the use of art to enhance empathy among medical students,3 4 we present the findings from an arts-based workshop designed to both understand and help medical students cope with their psychosocial stressors.

Jungian psychology and mandalas

Achieving balance is the primary goal of Jungian psychology.5 To this end, through both his own personal experience and his professional clinical work, Jung came to appreciate the benefit of creating mandalas.6 Mandala is a Sanskrit word for circle or centre, and refers to art created within or with reference to the form of a circle. Historically, the mandala is a religious or ritual form designed along specific guidelines. When used individually or therapeutically, individuals are free to spontaneously create their own forms while making use of the circle as a symbol of the self at a particular moment in time. The mandala allows for psychological integration of conscious and unconscious, while promoting meaningful self-reflection.7 Temporarily retreating into a symbolic world provides opportunities for achieving integration of conscious and unconscious mind and spirit. Jung referred to this process as active imagination.8 Although he did not specify rigid steps in this process, in general, it involves focusing on an intention or emotion, creating art spontaneously and then reflecting on the resulting images.

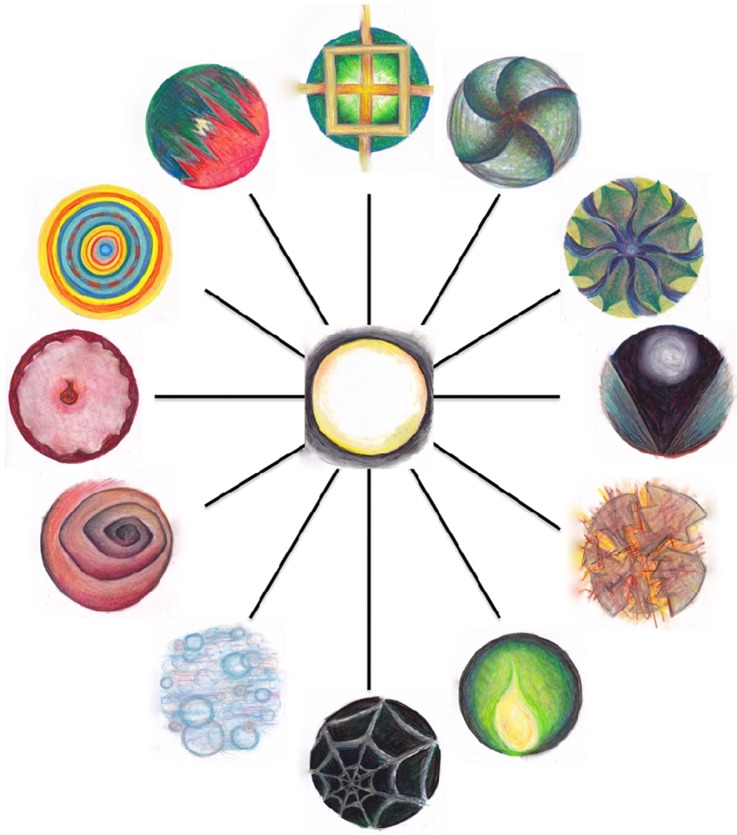

Fascinated by Jung's work, art therapist Kellogg9 began using mandalas in her work with psychiatric patients. From her vast collection of mandalas, she identified 13 mandala patterns that she referred to as the ‘Archetypal Stage of The Great Round of Mandala’ (often abbreviated to the ‘Great Round’). For each of the patterns, she identified associated archetypal, psychological and emotional themes that she saw as various ‘states of consciousness’ (p. 49) (figures 1 and 2). Hillman saw great benefit in identifying archetypal content of an individual's psyche in order to understand motivations, as such ideas suggest aspects of the general human condition.10 Further, through reflecting on one's own psychological experiences through metaphor, individuals are able to arrive at new insights that are, otherwise, limited by a focus on literal or actual events. With this new understanding, individuals are in a better position to assess their current state, discover discrepancies in how they view themselves and identify missing areas that are necessary for psychological balance.

Figure 1.

The Archetypal Stages of the Great Round of Mandala: illustration of stages (mandala images were created by the first author as inspired by Kellogg's work).

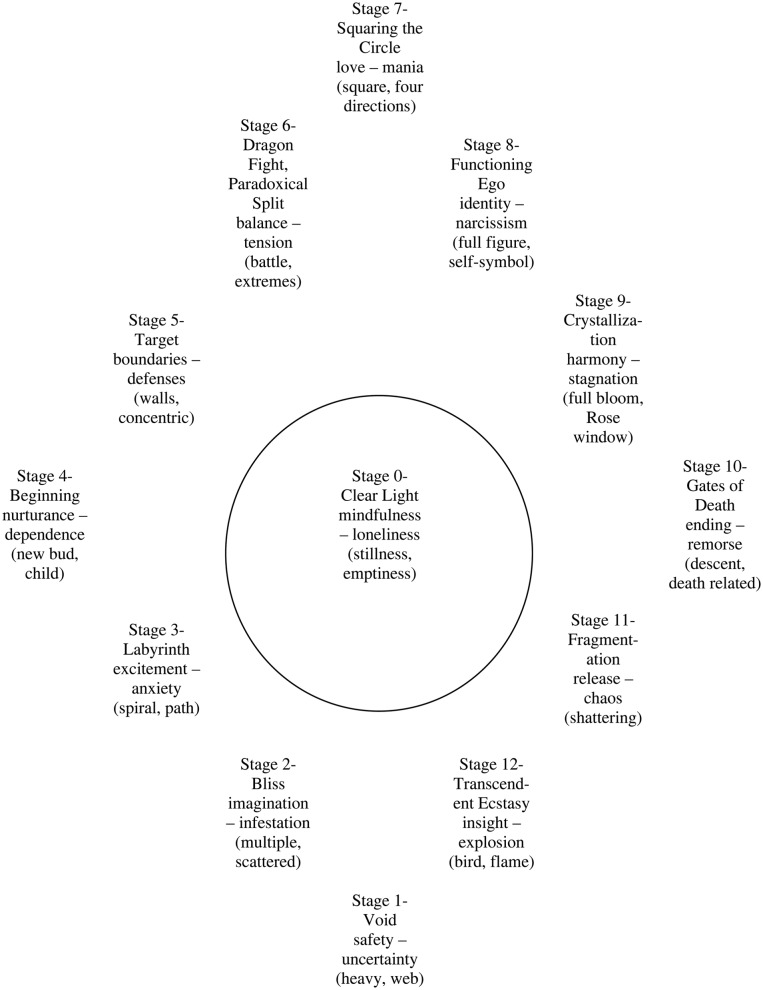

Figure 2.

Brief overview of the Great Round (stage number and name, psychological tasks, representative symbolic images).

The Great Round was intentionally arranged as a circle to promote a notion of holistic well-being. The sequential nature of the stages denotes development that mirrors Jung's studies of alchemical change as a metaphor for psychological growth. This sequence is readily apparent when looking at the quadrants of the Great Round as divided into incubational (Stages 1–3), developmental (Stages 4–6), actualisation (Stages 7–9) and transcendental stages (Stages 10–12). With the exception of Stage 0, which is situated in the centre, each stage has a counter stage to promote energy and provide balance. It is important to note that in keeping with Jungian theory, Kellogg's stages do not indicate healthy or pathological states. Every stage represents a normal aspect of human consciousness and development that is experienced repeatedly over one's lifetime. Distress is not caused by which stage a person is in, but rather by how one relates to or adapts to their current state of consciousness.

Mandala as tool for self-awareness

Henderson et al,11 found that creating mandalas, when compared with other forms of art, resulted in decreased depression and anxiety, as well as, significant reductions in trauma symptoms. Several art therapists have described the usefulness of mandalas for reducing anxiety, as well as, for increased self-awareness.12–14 Not limited to clinical settings, mandalas have been used for general wellness,15 as well as, with health professionals and nursing students.16 End-of-life care workers created mandalas to help them become more focused and aware of their feelings as a first step towards recognising and reducing burnout.17 18 Similarly, nursing students assigned to create mandalas found the process personally meaningful as it enabled them to experience a sense of self-discovery in a non-threatening manner.19 However, in this study, researchers focused on the process of creating mandalas, but did not provide much information on the images produced or their implication for participant well-being.

As far as we are aware, mandala making is a novel way of engaging medical students in the process suggested by Jung for creation and reflection. Further analysis of the content of the mandalas would contribute a new approach to understanding medical students’ psychological state.

Methods

Objectives

This qualitative research study intended to discover how creating mandalas might provide medical students with an opportunity for reflection on their current psychological state. We specifically sought to identify common mandala patterns and associated archetypal themes, which may reveal the concerns and well-being of the students. This information could have direct implications for training in the medical humanities and in initiatives to monitor and address student well-being.

Research design

This study used a qualitative research design.

Ethical review

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties at The University of Hong Kong (Ref. No. EA021112).

Sampling

The target participants were the two cohorts of medical students (n=320) enrolled in their third year of medical studies in the 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 academic years. As part of their year 3 family medicine rotation, students were required to attend a single 2½ h art workshop in the art studio at the Centre on Behavioral Health, a holistic health research centre of The University of Hong Kong.

Procedure and data collection

An art therapist (first author) was selected to facilitate this workshop in order to help students create art that was personally meaningful and focused on self-awareness. After entering the art studio, students received a briefing from the art therapist about the nature of the workshop as an opportunity to engage in art making for self-awareness and as a means towards burnout reduction. The art therapist also explained that the workshop was based on principles of art therapy. As such, the time in the studio was an opportunity to experiment with art materials and be creative. Therefore, no prior drawing and painting skills were required or expected. Instead, students were introduced to the art therapy expectations related to spontaneity, creating images that were personally meaningful and working within their current skill levels. The students were told that their art would not be judged by traditional aesthetics, but rather by their own subjective feeling that their final art felt as complete or finished as possible.

Participants were introduced to the use of the mandala as a Jungian-inspired art process designed to enhance self-understanding. After a brief breathing exercise designed to focus their attention, they had 45 min to use any of the drawing or painting materials of their choosing to create a mandala by answering the question, ‘How am I right now’? If students struggled during art making, the art therapist would offer guidance as needed in order to facilitate comfort with art materials and reduce frustration with the creative process. Following art-making, they completed reflective writing by writing a title, description and indication of what their art meant to them. Students were then divided into small groups based on finding other mandalas that were similar in subject matter, composition, colour pattern or intuitive association. Lastly, the art therapist facilitated a large group discussion on the experience and related discussion themes to self-awareness as a primary method towards burnout reduction, patient-centred care and stress management. At the conclusion of the workshop, the art therapist informed the students about the research study and invited them to submit their mandalas and reflective writings. This step was taken to ensure that students felt comfortable engaging in the workshop as intended before deciding whether they wanted to participate in the study.

Data analysis

The mandalas were analysed according to a priori or predetermined themes as described in the Great Round.20 Each mandala was first assessed according to compositional pattern and symbols used to determine a particular stage of the Great Round. Then the title, description and reflective writing were analysed for themes. If there was a discrepancy between the stage assigned to the mandala and the stage assigned to the writing, then the stage assigned to the writing was used in order to honour the intentions and personal interpretations of the participants. This method is endorsed in Kellogg's writings. Although she emphasised the symbolic, she honoured individual associations to their own art. After this process, each mandala was categorised into one stage of the Great Round.

Rigour

The primary assessor (first author) was specially trained in Kellogg's theory, and has used it in clinical and research applications for the past 15 years. If it was difficult to determine dominant themes of the reflective writings, coresearchers and colleagues were asked to read the writings and offer their opinions of the emotional and psychological content expressed by the participants. The primary assessor then related these ideas to the themes of the Great Round. To ensure accuracy and reliability, approximately 10% of the mandalas and associated writings were independently analysed by a senior teacher of Kellogg's work.

Results

Participants

Of the 320 students, 241 students attended the mandala workshop and 180 (table 1) submitted their mandalas and reflective writing for the research study.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n=180)

| Gender | n |

| Women | 76 |

| Men | 97 |

| Missing data | 7 |

| Age | |

| 18–25 | 171 |

| 25–29 | 4 |

| Missing data | 5 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Chinese | 173 |

| Missing data | 7 |

Overview of results

The art demonstrated many ways that the students were able to make use of mandala making to achieve self-awareness and discover coping methods. For example, an image described as ‘a circle of darkness inside a prison’ also contained spontaneous ‘golden threads’, which prompted the reflection ‘there is beauty even in the realistic and relatively depressing world’ (figure 3). Figure 4 describes the frequency of the stages, whereas figure 5 offers examples of mandalas created by the participants for each of the 13 stages.

Figure 3.

Battle.

Figure 4.

Frequencies of stages individually, by axis and by quarter.

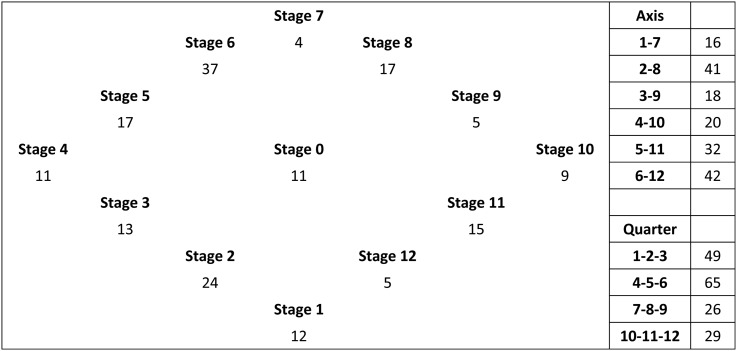

Figure 5.

Great Round (created from mandalas created by participants).

In keeping with a Jungian perspective and Kellogg's framework, the results are presented according to the axes of the Great Round in order to demonstrate the continuum of experiences that relate to each stage at the end of any given axis. The exception is Stage 0, as it is in the centre and not situated on any one axis. Direct quotations are from the participants’ written reflections.

Stages 6/12 axis

Thirty-seven mandalas, the category with the highest frequency, were coded as Stage 6—Paradoxical Split, Dragon Fight. This stage entails either a conflict or balance of internal opposites between ‘two sides’. An example of conflict was described in the artwork titled Volcano. The reflection described inner feelings of calm (‘comfortable and undisturbed’) contrasted with surrounding violence (‘rocks and high temperature fluid that can even melt our bones’). Other illustrations of conflict include ‘my conflicting values’, ‘how beautiful this period of my life is, but how it oversees a chaotic sea of problems’, and a brainstem ‘half of which is cold, meticulous knowledge while the other…all the goodies in life’. The aspect of balance was evident in just 11 images, including Displacement (see figure 5), which shows a dynamic of positive blue elements and negative black elements. The introduction of the black can induce ‘frustration and fear’, but enhancing the blue can ‘impact me so that things turn out better’.

Demonstrating how conflict can lead to solutions, five images contained the themes of Stage 12—Transcendent Ecstasy, which represents celebration, hope and insight. Three students described hope in the artworks titled Hope in the Midst of Storm (‘I feel that life is always changing, and for everything that happens in my life- they have their own beauties’), Sunrise (‘There is always hope… Dawn will eventually come and no matter how long is the night’) and Beyond the Death (‘after death…a stage of life…hope’). The other examples included ‘a bright flame amidst a chaotic background’ (see Ember figure 5) and a bird in flight ‘seeking a way to correct faults of this world’.

Stages 2/8 axis

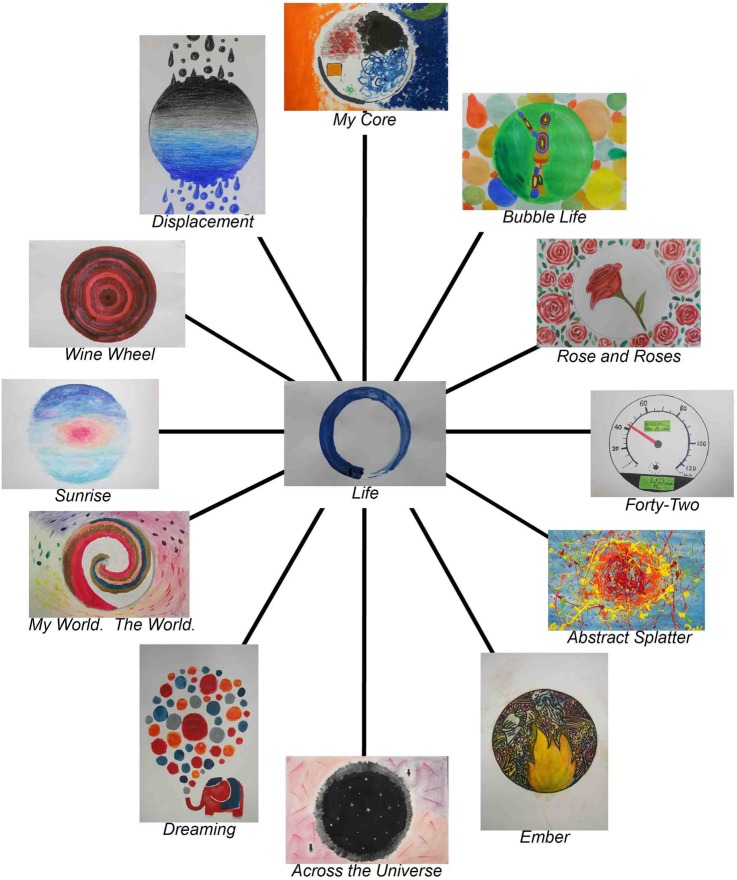

Stage 2—Bliss relates to peace and imagination, but also disassociation, diffusion and unstoppable growth. Twenty-four mandalas pertained to this stage. Of these, 10 of the images could be described as one student wrote, ‘a state of serenity and peacefulness of mind’. The uncontained aspect of this stage was described by one student as, ‘I just come up with everything I want to express in my head. And I do not want to be trapped in the circle so I draw something outside the circle’ (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Life (example of the Great Round Stage 2).

In contrast to a lack of definition and endless possibilities, Stage 8—Functioning Ego pertains to secure identity, individuality and direct expression of feelings. Of the 17 mandalas coded in this stage, a description of certainty accompanied an image titled I Am, There I Am with the phrase, ‘I feel more certain to my path of life’. An image of a person composed of many ‘bubbles’ and concentric circles was described as, ‘Every person is a unique individual. We live in our own bubble and have our own life’ (see Bubble Life figure 5). Three of these images specifically referenced acquiring a doctor identity. An example is a drawing titled Listener. The image of a stethoscope curling into a heart that extended beyond the perimeter of the mandala described how the student has been able to ‘gain the confidence’, ‘build up the relationship with the patient’ and ‘think “out of the bubble”’.

Stages 5/11 axis

Seventeen mandalas were coded as Stage 5—Target, which pertains to boundaries, defences and routines. The layering pattern of Stage 5 relates to learning and growth. This aspect was described by a student who created an image of concentric circles and the metaphor of wine to describe ‘degree of maturation… This resonates with my life stages and growth’ (see Wine Wheel figure 5). Six referenced boundaries between people or between one's internal aspects. Some examples include the necessity to maintain a ‘composed appearance’ or ‘Try to block my feelings from the unhappy things’. Three students described wanting to maintain order, while another wrote about the fatigue of unchanging routine.

In contrast to the containment of Stage 5, 15 mandalas were coded as Stage 11—Fragmentation that relates to psychic shattering or chaos. The image Life in Handcuffs described this feeling as, ‘It reflects my internal struggles and all the bottle-up emotions that no one seems to recognise or understand’. In another example, a student wrote, ‘my thoughts are actually quite scattered, although it might look a bit more formed from a distance’. A similar idea was expressed in Tied to Medicine. This image shows a mandala in which different aspects of life are portrayed in different wedges that do not have a central or unifying core. Although such feelings of disorder can be difficult to endure, it can also promote creativity. The creator of Abstract Splatter (see figure 5) wrote, ‘I was feeling excited, adventurous, creative and above all, joyful. I wanted to spread my joy to other calmer, composed people, and create a wonderful orderly chaos amidst the homogenous world’.

Stages 4/10 axis

Eleven mandalas were coded as Stage 4—Beginning. This stage relates to being nurtured or dependent on another, such as receiving ‘a lot of support and encouragement’ from family and being ‘loved by everyone around me, and cared by them’. Three students depicted a boat floating gently to represent these ideas. This state of nurturance is often in relation to the necessary support required in new beginnings. Some examples include a new bud seen through a keyhole or the image of a ‘first beam of light… To people who start another new page’ (see Sunrise figure 5).

Beginning is on the opposite end of ending. Stage 10—Gates of Death includes review and letting go, but often sadness as an ending is near. Nine students were coded within this category. A figure attempting to move towards a green light experienced ‘sadness, regret, self-blame and a loss of purpose and orientation’. The struggle of this stage was seen in an image of a disintegrating sphere with the reflection, ‘The new concept seems so attractive to me, but I kind of don't want to give up the old one I have had’. One of the themes of this stage is descent, which was observed in the image described as a ‘fallen explorer lost his bag and is surrounded by unknown beasts, boulders fall around him’. The Sunset contained a reflection of regret, ‘I wish I had more time to enjoy the simple things in life and do more of the things I like’. A speedometer displaying the number 42 (see Forty-Two figure 5) was described as:

There is a special meaning concerning the number “42” in Japanese culture which means “death.” But to me, this number has another meaning – failure. The markings of the speedometer go up to 125 km/h, showing that one originally should have the potential to go to the maximum of one's own strength, but at times one has depleted his or her own resources (as seen in the “fuel low” signal).

Stages 3/9 axis

Thirteen students described feelings of a powerful moving-forward sensation or a calling that pertain to Stage 3—Spiral, Labyrinth. Drive was described as, ‘some sense of passion and energy, bursting out in different ways’. The notion of being on a path, but without clear knowledge of the end was described as ‘a long tunnel’, ‘dark tunnel’, ‘pathway’ that perhaps leads to ‘a world of mystery lies beyond…unexpected events await one's discovery’. Similarly, a mandala titled The Direction contained the reflection, ‘I see a piece of land faraway… I'm still searching out’. The inability to adequately describe this state was revealed in the comment, ‘I don't particularly have anything on my mind. I just feel like there's something inside that's keeping me going’. That internal drive might relate to ‘showing a dynamic process’ (see My World. The World. Figure 5).

Lying opposite Stage 3, Stage 9—Crystallisation relates to fruition and connecting to the world beyond oneself. Five mandalas were coded under this state of consciousness. The rose in full bloom is representative of this stage (see Rose and Roses figure 5) and described by one student as, ‘It is easy to feel alone and insecure at times, but as long as you open up and see the world in a more optimistic way, the world is actually filled with colours and pleasant surprises’! The idea of completion can also lead to a feeling of stagnation. One student who drew a globe wrote, ‘Daily life is quite monotonous and I always want to have some stimulation’. To end this monotony, the student wrote, ‘I really want to get more variable experience, not just staying in one place…’, which demonstrates a desire for Stage 3.

Stages 1/7 axis

Twelve mandalas related to Stage 1—The Void as demonstrations of existential concerns and feelings of heaviness. An example of the existential is a mandala that takes the patient's perspective of many doctors looking down accompanied by the student's questions and observation, ‘What are we doing? What am I? Something scary within a dark void’. The feeling of stress was described as a burden as captured in the portrayal of ‘a huge weight’. Despite a painting of a sunflower, the space within the mandala of a dark colour and the archetypal pattern of a net contained the reflection, ‘I've been feeling down…I miss feeling energetic and positive’. The opportunity to peer into such a ‘black hole’ allowed for new realisations described as how ‘Stars twinkle bright against the darkness’ (see Across the Universe figure 5).

On the opposite end of the axis, four students created mandalas representative of Stage 7—Squaring the Circle. This stage relates to the integration and union of opposites. A mandala that shows yellow and blue forms joining to form a central green diamond was described as, ‘Sometimes things can merge to give a new colour but some other times, colours merge while pertaining to their own quality’. The painting titled My Core (see figure 5) displayed the quaternary pattern of this stage in contrast to a background of opposite colours clashing with the reflection, ‘Many[chaotic events] are happening around me. But the deepest part of me remain[s] untouched’.

Stage 0

Eleven mandalas were coded as Stage 0—Clear Light. This stage relates to mindfulness and centredness, but can also relate to isolation. One student described ‘danger around…yet, the white circle at the centre stays calm and stable’. As a way to ensure such stability, another student reflected:

Life is every day, every hour, every second. Life is what we do, what we think at every moment. More importantly, life is not about oneself. Everything is connected in this world, as all of us (and all creatures) are part of “life”. (see Life figure 5)

Identifying the Chinese ideal state of health, another student identified her image as ‘inner peace and harmony’ and ‘the homeland of our heart’. The potential possibility aspect of Stage 0 was captured in the statement ‘one of the wonder and amazement, and the wonders and mysteries that lies in the unknown…wondering what could have been, what can be, and the wonders of the unknown’. The mindful observation qualities or third-eye aspect of Stage 0 was revealed in a drawing of an eye accompanied by the statement, ‘I want to have a more thorough look on the things around me’.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse medical student mandalas through a Jungian perspective using Kellogg's Great Round. As a result, this study offers implications for how mandalas may be used within medical education to help students become more self-aware and to develop personal well-being. Although this use of art is helpful for individuals, noticing the patterns of several students may demonstrate some of the struggles, strengths and concerns of the students overall. Determining common patterns as they relate to archetypal content provides insight into the current state of the medical students, which provides opportunities for additions to the curriculum.

Implications for medical education

Professional identity as a doctor

Just over half of the mandalas were coded as falling along either the Stages 6/12 or 2/8 axes. These findings indicate that these areas may be most pressing for the students at this stage of their development. The 6/12 axis pertains to the continuum of balancing internal opposites to discover meaningful resolution. The students who described awareness of internal polarities either experienced them as in balance or in conflict. Medical school, and especially the first of the clinical years, can be a time to experience stress and uncertainty.21 Students encounter life and death, competence and incompetence, novice and healer. This may also be a time in which students have to reconcile their motivations for pursuing medicine with the realities of being in the profession. Kellogg described this state of consciousness as a natural stage of development, with particular relevance to identity formation. As only 11 students were categorised as Stage 6, indicated balance, and only five were classified as Stage 12; many of the students expressed experiences of conflict. This demonstrates an imbalance, which may need to be addressed. In order to ensure that the opposites manifest as maturity and the achievement of insight, individuals in this stage should be encouraged to explore the dualities, notice their relation to each other and learn strategies for maintaining balance.

In relation to identity, the 2/8 axis describes movement from formlessness to full formation. Metaphorically, the images of stardust settling or cells multiplying coalesce into specific beings and forms. As students are developing their physician identities, it is not surprising that this axis was prominent. Most of the mandalas coded as Stage 2 related to peacefulness and relaxation. It is possible that this was a result of the guided imagery and potential soothing nature of the creative process. It may also describe the need that medical students have for moments of intentional stress management. Medical students, with heavy workload and also anxiety in facing pain and suffering, often have little support or time to think and relax.22 This stage also relates to unfettered growth and imagination. Its prominence could be an indication that there are aspects of themselves in the process of coalescing, movement from Stage 2 to Stage 8, or continued questions on professional role, movement from Stage 8 to Stage 2. The lesson of this axis is that students should be supported in the development of their professional identity, while still giving them room to imagine possibilities for themselves. Reflection and reflective practice is increasingly being recognised as a crucial means of developing professional identity from the earliest stages of medical education,23 and mandala making is one means through which this could be enhanced.

Psychosocial characteristics and well-being

Another frequently indicated area pertained to the 5/11 axis, which was nearly perfectly balanced. The balance between order and chaos is the feature of this axis. Keeping in mind that each stage has its own positive and negative qualities, the balance should not obscure that there were students coded as Stage 5 who were attempting to block off emotions or impose order to manage being overwhelmed. Both order and chaos are components of positive mental health, but only when properly balanced. As a whole, the group was well balanced. Still, individuals may benefit from personal development of ability to manage the unknown or how to engage flexible routines.

The 4/10 axis, which pertains to beginnings and endings, was also balanced. Although there were relatively few mandalas classified along this axis, the identification of supportive relationships is encouraging. At this stage of their career, students move between states of needing to be nurtured while also begin challenged. Given the academic rigour and the immense knowledge to obtain, often, the aspect of feeling supported is not as apparent to the students. Based on some of the mandalas, it does seem that they may need some support with handling endings and transitions. The lessons associated with Stage 10 speak of the importance of attending to losses that come with transitions and taking the time to review. Relatively few students seemed to have this state as a focus. Still helping them cope with changes in their roles, inevitable deaths that they will encounter and how endings relate to beginnings may be helpful.

Both the 3/9 and 1/7 axes were imbalanced at approximately the same ratio of 3:1. The 3/9 axis demonstrates urging and completion. Individuals experiencing this tension may be torn by a feeling pointing them or pulling them in a particular direction, even if the end goal is not readily unidentifiable. In contrast, moments of completion may be accompanied by boredom or irritation at the lack of novel energy. The mandalas categorised along this axis overwhelmingly fell on Stage 3. The indications of being on a path are appropriate for learning to be a doctor. However, if not managed well, this energy and uncertainty can lead to anxiety or distress regarding the future. Students may benefit from learning how to accept the uncertainty of this time and how to best direct their energy.

The 1/7 axis describes the process of integrating existential concerns into living a dynamic existence. This axis was heavily weighted on the existential side of Stage 1. Given their educational level and encounters with patient suffering, it makes sense that students would have many questions regarding their purpose and motivation to pursue medical studies. As a necessary state of development, it is important to allow for moments of intense introspection. When left unattended, these questions can burden students or trap them in questions that deny their ability to move forward. Students may benefit from helping them periodically review what led them to the field of medicine, identify their own existential dilemmas and how their training can lead to new understandings on life, health and healing.

The presence of Stage 0 indicates that it is possible for medical students to access internal resources and potential to pay attention to themselves and their environment. As all of the mandalas classified to this stage focused on qualities of mindfulness and strength, rather than the negative qualities of isolation or shock, students appear to already possess the tools for constructive stress management. Although some students accessed this state quite readily, it can be nurtured in others. One of the benefits of Stage 0 consciousness is that it allows for a slight detachment to observe where one's experiences fit into the whole cycle of development, appreciate that stage of development and then willingly re-engage.

Medical students’ psychological distress is an issue worldwide and also in our programme.24 25 Proactively recognising students who may be feeling overwhelmed or distressed in a non-threatening and constructive way is not easy, and an approach such as mandala making under the guidance of a healthcare professional can be a first step towards acknowledging and addressing the human side of medical trainees, and the psychological burdens they may carry.

Limitations

Despite these findings for the use of mandalas to assess medical students, there are limitations to this study. Students only completed a single mandala in a single session. Although the mandalas may indicate their state at the time of the workshop, we should be careful that we do not make large-scale generalisations between the created art and the totality of the students’ character. Even though an isolated mandala may not totally reflect each individual student, the large sample size was useful for identifying patterns. An additional limitation is that Kellogg's theory has not been extensively researched, and like Jungian psychology, in general, assumes the presence of the collective unconscious and archetypes. When considered within this framework, the findings may still be considered valid. The fact that so many of the themes were identified in the study does point out the cross-cultural application of Kellogg's archetypal states. Each mandala was classified according to only one stage to aid the research, but human experience is multileveled and complex. In addition, the process of creating art and reflecting on it changes one's state, which was not captured in this study. As such, the art and writing reflected their state of being at the moment of creation, but not what might have emerged as a result of further reflection through the small and large group discussions. Lastly, the sample is biased as the desire to preserve autonomy, and fidelity meant some students were not represented due to their lack of desire to participate. As all of the stages of the Great Round were noted in the sample and casually observed during the workshop, the sample may still be considered as offering useful ideas for further workshops.

Conclusion

According to Jungian psychological theory, we all have access to the wealth of archetypes that exist in the world. At different moments of life, certain ones are more active or present, while others seem absent or dormant. Archetypal psychology reminds us to pay attention to all of the areas in order to maintain psychological well-being. By helping medical students connect their experiences to the general human condition, they can attend to and appreciate each stage of their development. Mandala making as a reflective activity also provides insight into evolving professional identity and the psychological state of students, which may help medical educators as they nurture the development and well-being of our future doctors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Centre on Behavioral Health at The University of Hong Kong for the use of their art studio and to Carol T Cox for consulting on the applications of the ‘Archetypal Stages of the Great Round of Mandala’.

Footnotes

Contributors: JSP and JYC designed the study. JSP led the data collection, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. JYC and JPYT contributed to data analysis and revised the manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties at The University of Hong Kong.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cole TR, Carlin N. The suffering of physicians. Lancet 2009;374:1414–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61851-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong JGWS. Doctors and stress. Hong Kong Med Diary 2008;6:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potash J, Chen J. Art-mediated peer-to-peer learning of empathy. Clin Teach 2014;11:327–31. 10.1111/tct.12157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potash JS, Chen JY, Lam C, et al. Art-making in a family medicine clerkship: how does it affect medical student empathy? BMC Med Educ 2014;14:247 10.1186/s12909-014-0247-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storr A. The essential Jung. New York, NY: MJF Books, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung CG. Memories, dreams, and reflections. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung CG. Mandalas. Appendix to Concerning Mandala Symbolism. Collected Works, Vol 9 Part 1: The archetypes of the collective unconscious. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chodorow J, ed. Jung on active imagination. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellogg J. Mandala: Path of beauty. Mandala Assessment and Research Institute, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillman J. Re-visioning psychology. New York, NY: Harper, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson P, Rosen D, Mascaro N. Empirical study on the healing nature of mandalas. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 2007;1:148 10.1037/1931-3896.1.3.148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couch JB. Behind the veil: Mandala drawings by dementia patients. Art Therapy 1997;14:187–93. 10.1080/07421656.1987.10759280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox CT, Cohen BM. Mandala artwork by clients with DID: Clinical observations based on two theoretical models. Art Therapy 2000;17:195–201. 10.1080/07421656.2000.10129701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry NA, Kasser T. Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? Art Therapy 2005;22:81–5. 10.1080/07421656.2005.10129441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisarik CT, Larson KR. Facilitating College Students’ authenticity and psychological well-being through the use of mandalas: an empirical study. J Humanist Couns 2011;50:84–98. 10.1002/j.2161-1939.2011.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall MC. Creative learning: the mandala as teaching exercise. J Nurs Educ 2003;42:517–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potash JS, Chan F, Ho AH, et al. A model for art therapy-based supervision for end-of-life care workers in Hong Kong. Death Stud 2015;39:44–51. 10.1080/07481187.2013.859187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potash JS, Bardot H, Wang XL, et al. Mandalas as indicators of burnout among end-of-life care workers. J Appl Arts Health 2014;4:363–77. 10.1386/jaah.4.3.363_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahar DJ, Iwasiw CL, Evans MK. The Mandala: first-year undergraduate nursing students’ learning experiences. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 2012;9 10.1515/1548-923X.2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Method 2003;15:85–109. 10.1177/1525822X02239569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nevalainen M, Mantyranta T, Pitkala K. Facing uncertainty as a medical student—a qualitative study of their reflective learning diaries and writings on specific themes during the first clinical year. Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:218–23. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephenson A, Higgs R, Sugarman J. Teaching professional development in medical schools. Lancet 2001;357:867–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04201-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ 2009;14:595–621. 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med 2006;81:354–73. 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong JGWS, Patil NG, Beh SL, et al. Cultivating psychological well-being in Hong Kong's future doctors. Med Teach 2005;27:715–19. 10.1080/01421590500237945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]