Summary

Background

With over one million Syrian refugee children in the region, we undertook this study to characterize care‐seeking behaviors and health service utilization for child refugees with the aim of informing humanitarian programming for non‐camp settings in Jordan.

Methods

A survey of Syrian refugees living outside of camps in Jordan was conducted using a 125 × 12 cluster design with probability proportional to size sampling to obtain a representative sample. The questionnaire focused on access to health services, including a module on care seeking for children.

Results

Care seeking was high with 90.9% of households with a child less than 18 years seeking medical care the last time it was needed. Households most often sought care for children in the public sector (54.6%), followed by private (36.5%) and charity sectors (8.9%). Among child care seekers, 88.6% were prescribed medication during the most recent visit, 90.6% of which obtained the medication. Overall, 49.4% of households reported out‐of‐pocket expenditures for either the consultation or prescribed medications at the most recent visit (mean $US21.1 and median $US0).

Conclusions

Syrian refugees had good access to care for their sick children at the time of the survey; however, this has likely deteriorated since the survey because of the withdrawal of free access for refugees. The number of refugees in Jordan and relative accessibility of care has resulted in a large burden on the health system; the Jordanian government will require additional support if current levels of health access are to be maintained for Syrian refugees. © 2016 The Authors. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Keywords: Syria, child health, Jordan, refugees, humanitarian assistance

Introduction

The landscape of forced displacement has evolved over the past two decades towards urban settings in middle‐income countries. Additional demographic and epidemiological shifts have forced humanitarian agencies to adapt traditional camp‐based assistance modalities to strategies better suited to the unique vulnerabilities, needs and capacities of both urban refugee and host communities (Spiegel, 2010; Gutierres & Spiegel, 2012). Ensuring accessibility and adequate coverage levels of health services is a challenge for non‐camp populations given that improving existing infrastructure often requires considerable amounts of time. In Jordan, which is host to more than 628 000 registered Syrian refugees, the additional refugee caseload is immense as are the costs of providing health services and upgrading facilities to cope with the increased burden (Murshidi et al., 2013; UNHCR, 2015d 2015a).

The highest mortality rates among displaced populations worldwide are in children younger than 1 year of age, followed closely by children under 5 years of age (Toole & Waldman, 1990; Toole & Waldman, 1997: Guha‐Sapir & Panhuis, 2004). Since the beginning of unrest in March 2011, the Syrian conflict has affected an estimated 14 million children (United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2015). There are an estimated 4.6 million Syrian refugees who have fled to Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and other countries in the region (Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS), 2014). Children under the age of 5 and 5–17 years of age account for 17.7% and 51.1% of the Syrian refugee population, respectively, which is higher than the average global proportion of child refugees (UNHCR, 2015b, 2015c). In Jordan, a majority of Syrian refugees reside in host communities and receive health services through existing health infrastructure (UNHCR, 2015b 2015d). There is no end in sight to the Syrian crisis and the struggle of host countries to provide adequate healthcare for both refugees, and their own populations will likely increase in the coming years (The New York Times, 2015). This study aimed to assess the access to and utilization of health services among Syrian refugee children in non‐camp settings in Jordan.

Methods

A cross‐sectional survey of Syrian refugees in Jordan was conducted in June 2014 to characterize health‐seeking behaviors and issues related to accessing health services. A two‐stage cluster survey design with probability proportional to size sampling was used to attain a nationally representative sample of Syrian refugees living outside of camps. A sample size of 1500 was calculated for key study objectives based on the most conservative prevalence rate estimate of 50%, a power of 80% to detect a 10% difference between subnational regions for key indicators, a design effect of 2.0 to account for the cluster sample design and a 10% non‐response rate.

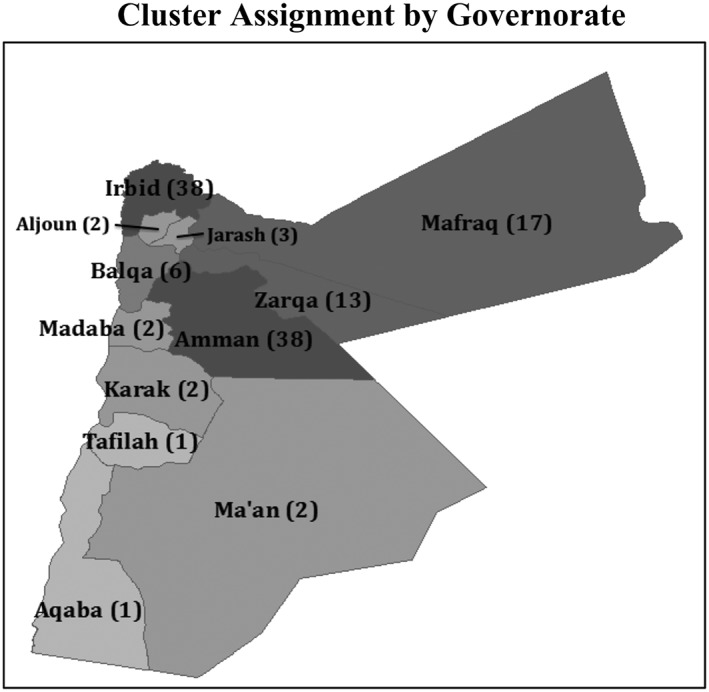

Given the concentration of Syrian refugees and logistical considerations relating to the country's small size and good transportation infrastructure, a 125 cluster × 12 household design was chosen. Probability proportional to size sampling was used to assign clusters to subdistricts using UNHCR registration data, assuming that non‐registered refugees had similar residence patterns. The final cluster assignment included 38 clusters (30%) in Amman governorate, 38 clusters (30%) in Irbid governorate and 49 clusters (40%) distributed proportionately in the remaining governorates (Figure 1). In each cluster, UNHCR randomly selected five registered refugee households listed as living in that cluster's assigned subdistrict. Households were then called by the study team; the first household among the five that was currently residing in the specified subdistrict and agreed to meet with the study team was used as the index household for the cluster. The study team met this household and enquired about other Syrian households living in the vicinity, both registered and unregistered. The information collected from the index household was not used in this analysis, in an effort to minimize the bias in the data from being overly representative of registered refugees. The household(s) to which the index household referred the interview teams were then interviewed using the complete questionnaire and were included. Household heads and primary caretakers of children were prioritized to answer questions on behalf of the households and its members. Household members were defined as people who share a dwelling space and share meals, regardless of biological relation. At the conclusion of each interview, a referral was requested to the nearest Syrian household, and this process was used until 10 interviews were completed. Only Syrian households arriving in 2011 or after were eligible to participate; however, none of the households approached arrived before 2011.

Figure 1.

Cluster assignment by governorate

The questionnaire was developed by consensus between partner agencies and focused on health service utilization, access to care, barriers to care seeking, children's health and vaccination and chronic medical conditions. The questionnaire was translated to Arabic, and both a pre‐pilot test and a formal pilot test were performed. Interviewers underwent 2 days of classroom training on the questionnaire, e‐data collection using tablets, interview techniques, basic principles of human subjects' protections and sampling methods followed by 1 day of practical field training. To protect the anonymity of respondents, no information was recorded that could be used to identify the household or individuals, and verbal consent was obtained from all respondents. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min depending on the household size, number of children and individuals with chronic medical conditions. Data were collected on tablets using the Magpi mobile data platform by DataDyne LLC (Washington, DC, USA). Data were analyzed using stata 13 (College Station, TX, USA) and tableau desktop (Seattle, WA, USA) software packages and employed standard descriptive statistics and methods for comparison of means and proportions. The stata svy command was used to account for the cluster survey design so that standard errors of the point estimates were adjusted for survey design effects.

The study was reviewed by ethics committees at the World Health Organization (WHO), Jordan University of Science and Technology and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and was approved by the Jordanian Ministry of Health.

Results

A total of 1634 households were approached to participate in the survey. Of these households, 2.9% (n = 47) were not at home, 0.8% (n = 14) were already interviewed for this survey, and 1.4% (n = 23) declined to be interviewed. The final sample included 1550 households (with 9580 household members), which equates to a response rate of 94.7%. Overall, 64.6% of households had at least one child age 0–5 years and 89.6% had at least one child age 6–17 years. Children age 0–5 and 6–17 years accounted for 20.2% and 33.6%, respectively, of the survey population.

Care seeking and health service utilization

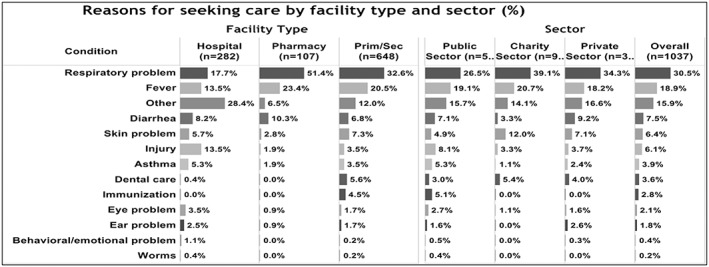

Respondents were asked to report on the most recent time a child in their household, age 17 years or younger, needed medical care (Table 1). A large percentage of households reported a child needing medical care within the month preceding the survey (68.5%). Overall, 90.9% of households reported medical attention was received the last time a child needed care; there were no significant differences in the care‐seeking rate by region (p = 0.520). Among the 9.0% that did not seek care, the primary reason reported was cost (68.0%). Other reasons include the following: child not being sick enough (7.8%); provider was perceived as having inadequate medications or equipment (5.8%); not knowing where to go (3.9%); and lack of transportation (2.9%). Care seeking was reported for the following conditions: respiratory illness (30.5%), fever (18.9%), diarrhea (7.5%), skin problems (6.4%) and injury (6.1%). The conditions for which care was sought were similar across the regions (p = 0.524) but differed significantly by sector (p < 0.001) and facility type (p < 0.001) (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Healthcare seeking in Jordan among Syrian refugee children

| Survey total (N = 1141) %95 CI | By region | Regional comparison p‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

North (n = 545) %95 CI |

Central (n = 535) %95 CI |

South (n = 61) %95 CI |

|||

| Received care last time it was needed* | 90.9 [88.9, 92.6] | 92.8 [89.9, 95.0] | 88.6 [85.5, 91.1] | 93.5 [84.8, 97.4] | 0.522 |

| Last time care was needed* | n = 1141 | n = 545 | n = 535 | n = 61 | |

| Less than 2 weeks ago | 41.9 [38.8, 45.1] | 45.8 [40.9, 50.7] | 38.3 [34.2, 42.6] | 38.7 [30.1, 48.1] | 0.249 |

| 2 weeks to less than 1 month ago | 26.6 [24.0, 29.3] | 24.8 [21.2, 28.8] | 27.9 [24.0, 32.1] | 30.6 [26.1, 35.6] | |

| 1 month to less than 3 months ago | 19.6 [17.3, 22.2] | 18.9 [15.5, 22.9] | 20.4 [16.8, 24.4] | 19.4 [15.9, 23.4] | |

| 3 months to less than 6 months ago | 7.2 [5.8, 8.9] | 6.3 [4.6, 8.4] | 8.6 [6.4, 11.5] | 3.2 [1.0, 10.0] | |

| 6 months to less than 1 year ago | 3.7 [2.7, 5.0] | 3.1 [2.0, 4.8] | 3.7 [2.4, 5.8] | 8.1 [3.5, 17.4] | |

| More than 1 year ago | 1.1 [0.6, 2.0] | 1.1 [0.4, 2.7] | 1.1 [0.5, 2.7] | 0 | |

| Reason for most recent care seeking** | n = 1037 | n = 506 | n = 474 | n = 57 | |

| Respiratory problem | 30.6 [27.6, 33.8] | 31.7 [26.9, 37.0] | 29.9 [26.1, 34.1] | 26.2 [19.0, 35.0] | |

| Fever | 18.8 [16.5, 21.4] | 16.3 [13.0, 20.3] | 20.7 [17.5, 24.4] | 24.6 [19.6, 30.4] | 0.545 |

| Diarrhea | 7.8 [6.2, 9.7] | 7.2 [5.1, 9.9] | 8.6 [6.3, 11.7] | 6.6 [2.6, 15.4] | |

| Injury | 6.0 [4.7, 7.5] | 6.1 [4.4, 8.4] | 6.4 [4.6, 8.7] | 1.6 [0.3, 9.0] | |

| Skin problem | 6.0 [4.7, 7.8] | 7.0 [4.9, 9.8] | 4.9 [3.2, 7.2] | 8.2 [3.0, 20.6] | |

| Asthma | 4.0 [3.0, 5.5] | 4.6 [3.0, 7.1] | 3.4 [2.1, 5.2] | 4.9 [1.4, 15.7] | |

| Dental care | 3.9 [2.9, 5.1] | 4.4 [3.0, 6.4] | 3.6 [2.3, 5.5] | 1.6 [0.3, 9.6] | |

| Immunization | 2.6 [1.7, 3.9] | 3.3 [1.9, 5.7] | 1.9 [0.9, 3.7] | 3.3 [1.1, 9.6] | |

| Eye problem | 2.0 [1.3, 3.1] | 2.2 [1.1, 4.2] | 1.9 [1.1, 3.3] | 1.6 [0.3, 9.3] | |

| Ear problem | 1.7 [1.1, 2.5] | 1.1 [0.5, 2.4] | 2.4 [1.5, 3.9] | 0 | |

| Behavioral/emotional problem | 0.4 [0.1, 0.9] | 0.6 [0.2, 1.7] | 0.2 [0.0, 1.3] | 0 | |

| Worms | 0.2 [0.0, 0.7] | 0 | 0.4 [0.1, 1.5] | 0 | |

| Other | 16.0 [13.9, 18.5] | 15.6 [12.4, 19.4] | 15.9 [12.9, 19.5] | 21.3 [15.0, 29.4] | |

| Location of most recent care** | n = 1037 | n = 506 | n = 474 | n = 57 | |

| Public primary healthcare center | 25.2 [21.5, 29.2] | 25.3 [20.0, 31.5] | 23.8 [19.0, 29.5] | 34.5 [17.9, 55.9] | 0.021 |

| Public hospital | 21.0 [18.3, 24.0] | 23.2 [19.4, 27.4] | 18.1 [14.6, 22.3] | 25.9 [13.3, 44.1] | |

| Private Jordanian clinic or doctor | 18.4 [15.7, 21.5] | 16.2 [13.0, 20.2] | 21.3 [17.1, 26.3] | 13.8 [5.7, 29.9] | |

| Pharmacy | 9.2 [7.3, 11.4] | 7.5 [5.3, 10.7] | 10.8 [8.0, 14.3] | 10.3 [3.5, 27.0] | |

| Public comprehensive center | 8.4 [6.6, 10.6] | 7.9 [5.6, 11.1] | 9.1 [6.5, 12.6] | 6.9 [2.7, 16.6] | |

| Non‐religious charity | 6.8 [4.9, 9.2] | 10.7 [7.5, 15.1] | 3.2 [2.0, 5.0] | 1.7 [0.3, 9.5] | |

| Private hospital | 6.2 [4.6, 8.2] | 4.6 [3.0, 7.0] | 8.2 [5.7, 11.7] | 3.4 [0.5, 20.5] | |

| Islamic charity | 2.1 [1.3, 3.3] | 3.2 [1.8, 5.4] | 1.3 [0.6, 2.7] | 0 | |

| Syrian doctor | 1.6 [0.9, 3.0] | 0.8 [0.2, 2.6] | 2.7 [1.4, 5.4] | 0 | |

| Shop or other | 1.2 [0.6, 2.1] | 0.6 [0.2, 1.8] | 1.5 [0.7, 3.0] | 3.4 [0.6, 17.6] | |

| Sector of most recent care** | n = 1037 | n = 506 | n = 474 | n = 57 | |

| Public sector | 54.6 [50.5, 58.6] | 56.3 [50.1, 62.3] | 51.1 [45.5, 56.6] | 68.4 [54.8, 79.5] | <0.001 |

| Private sector | 36.5 [32.7, 40.5] | 29.8 [25.0, 35.2] | 44.5 [38.9, 50.3] | 29.8 [18.3, 44.7] | |

| NGO/charity sector | 8.9 [6.6, 11.8] | 13.8 [9.8, 19.2] | 4.4 [3.0, 6.6] | 1.8 [0.3, 9.7] | |

| Facility type of most recent care** | n = 1037 | n = 506 | n = 474 | n = 57 | |

| Primary/secondary/private provider | 62.5 [59.0, 65.9] | 64.2 [59.4, 68.8] | 61.4 [55.9, 66.6] | 56.1 [45.3, 66.4] | 0.448 |

| Hospital | 27.2 [24.3, 30.3] | 27.7 [23.6, 32.2] | 26.4 [22.3, 30.9] | 29.8 [16.5, 47.8] | |

| Pharmacy or shop | 10.3 [8.3, 12.7] | 8.1 [5.8, 11.2] | 12.2 [9.5, 15.6] | 14 [3.9, 39.6] | |

CI, confidence interval; NGO, non‐governmental organization.

Per cent of all household index cases that needed care in Jordan.

Per cent of all household index cases that received care in Jordan.

Table 2.

Reason for most recent healthcare seeking in Jordan among Syrian refugee children by sector and facility type*

| By sector | Sector comparison p‐value | By facility type | Facility comparison p‐value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public %95 CI n = 566 |

Private %95 CI n = 379 |

Charity %95 CI n = 92 |

Primary/secondary %95 CI n = 648 |

Hospital %95 CI n = 282 |

Pharmacy %95 CI n = 107 |

|||

| Respiratory problem | 26.5 [23.2, 30.1] | 34.3 [29.3, 39.7] | 39.1 [28.8, 50.5] | <0.001 | 32.6 [28.7, 36.7] | 17.7 [13.6, 22.8] | 51.4 [42.5, 60.2] | <0.001 |

| Fever | 19.1 [16.1, 22.5] | 18.2 [14.4, 22.7] | 20.7 [12.7, 31.7] | 20.5 [17.4, 24.0] | 13.5 [9.7, 18.4] | 23.4 [17.0, 31.2] | ||

| Diarrhea | 7.1 [5.1, 9.6] | 9.2 [6.8, 12.5] | 3.3 [1.0, 10.0] | 6.8 [5.1, 9.0] | 8.2 [5.2, 12.6] | 10.3 [6.0, 17.1] | ||

| Skin problem | 4.9 [3.3, 7.4] | 7.1 [4.9, 10.2] | 12 [7.2, 19.1] | 7.3 [5.4, 9.6] | 5.7 [3.1, 10.3] | 2.8 [0.9, 8.4] | ||

| Injury | 8.1 [6.1, 10.8] | 3.7 [2.3, 6.0] | 3.3 [1.1, 9.4] | 3.5 [2.3, 5.4] | 13.5 [9.9, 18.1] | 1.9 [0.5, 7.1] | ||

| Asthma | 5.3 [3.7, 7.5] | 2.4 [1.2, 4.8] | 1.1 [0.2, 7.3] | 3.5 [2.2, 5.7] | 5.3 [3.2, 8.7] | 1.9 [0.5, 7.2] | ||

| Dental care | 3.0 [1.8, 4.9] | 4.0 [2.3, 6.8] | 5.4 [2.4, 11.8] | 5.6 [4.0, 7.6] | 0.4 [0.0, 2.5] | 0 | ||

| Immunization | 5.1 [3.4, 7.6] | 0 | 0 | 4.5 [3.0, 6.7] | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ear problem | 1.6 [0.8, 3.0] | 2.6 [1.4, 4.8] | 0 | 1.7 [1.0, 3.0] | 2.5 [1.2, 5.0] | 0.9 [0.1, 6.6] | ||

| Eye problem | 2.7 [1.5, 4.7] | 1.6 [0.7, 3.4] | 1.1 [0.1, 7.5] | 1.7 [1.0, 3.0] | 3.5 [1.9, 6.5] | 0.9 [0.1, 6.1] | ||

| Behavioral/emotional problem | 0.5 [0.2, 1.6] | 0.3 [0.0, 1.9] | 0 | 0.2 [0.0, 1.1] | 1.1 [0.3, 3.2] | 0 | ||

| Worms | 0.4 [0.1, 1.4] | 0 | 0 | 0.2 [0.0, 1.1] | 0.4 [0.0, 2.5] | 0 | ||

| Other | 15.7 [12.8, 19.2] | 16.6 [13.4, 20.4] | 14.1 [8.1, 23.5] | 12.0 [9.8, 14.8] | 28.4 [23.1, 34.4] | 6.5 [3.2, 12.8] | ||

CI, confidence interval.

Per cent of all household index cases that received care in Jordan.

Figure 2.

Reasons for seeking care by facility type and sector (%)

Among households that sought care for a sick child, approximately half (54.6%) went to public sector facilities (Table 1), including primary healthcare centers (25.2%), public hospitals (21.0%) and comprehensive health centers (8.4%). Another 36.5% sought care in private sector facilities, including private clinics (18.4%), pharmacies (9.2%) and private hospitals (6.2%). The remaining 8.9% of visits took place in the charity/non‐governmental organization (NGO) sector, including NGO facilities (6.8%) and Islamic charity facilities (2.1%). Statistically significant differences in care‐seeking location were observed by region (p = 0.021). A higher proportion of households in the South (68.4%) sought care at public facilities compared with the North (56.3%) and Central (51.0%) regions (p < 0.001). More than half (62.5%) of child healthcare seekers utilized a primary or secondary level facility, 27.2% sought care at hospitals, and 10.3% sought care in a pharmacy or shop; there were no significant differences by region in type or level of facility utilized (p = 0.448).

Among the child care seekers, 88.6% were prescribed medication during the most recent visit (Table 3); no significant differences were observed by region (p = 0.623). The proportion of children receiving a prescription varied significantly by sector type as follows: private facilities, 94.7%; charity/NGO facilities, 87.0%; and public facilities, 84.8% (p < 0.001). Of those prescribed medications, 90.6% were able to obtain all medicines; however, among the remaining 9.4%, the most common reasons for not receiving medicines were stock outs in public facilities (52.9%) and cost (37.6%).

Table 3.

Medication access among Syrian refugee children in Jordan

|

Survey total (N = 1037) %95 CI |

By region | Regional comparison p‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

North (n = 505) %95 CI |

Central (n = 474) %95 CI |

South (n = 58) %95 CI |

|||

| Prescribed medication during most recent health facility visit | 88.6 [86.1, 90.7] | 86.7 [82.5, 90.1] | 90.9 [87.9, 93.3] | 86.2 [75.8, 92.6] | 0.623 |

| By facility type* | |||||

| Public facility | 84.8 [81.0, 88.0] | 82.1 [75.6, 87.1] | 88.0 [83.5, 91.4] | 84.6 [69.1, 93.1] | 0.208 |

| Private facility | 94.7 [92.2, 96.4] | 94.7 [90.1, 97.2] | 95.3 [92.0, 97.2] | 88.9 [64.5, 97.2] | 0.472 |

| Charity facility | 87.0 [77.9, 92.6] | 88.6 [78.5, 94.3] | 81.0 [57.0, 93.2] | 100 | 0.819 |

| Able to obtain all medications prescribed at most recent visit** | n = 919 | n = 439 | n = 431 | n = 49 | |

| 90.6 [88.6, 92.3] | 90.4 [87.7, 92.6] | 91.4 [88.0, 93.9] | 86.0 [78.4, 91.2] | 0.733 | |

| Reason for not obtaining medications*** | n = 85 | n = 41 | n = 37 | n = 7 | |

| Medication out of stock at public facility | 52.9 [41.6, 63.9] | 56.1 [39.2, 71.7] | 48.6 [33.4, 64.2] | 57.1 [16.4, 90.1] | 0.948 |

| Could not afford the medication | 37.6 [27.6, 48.9] | 31.7 [19.1, 47.7] | 43.2 [28.1, 59.8] | 42.9 [9.9, 83.6] | |

| Medication out of stock at private pharmacy | 3.5 [1.1, 10.4] | 4.9 [1.3, 17.0] | 2.7 [0.4, 17.5] | 0 | |

| Chose a different treatment | 1.2 [0.2, 8.1] | 0 | 2.7 [0.4, 17.5] | 0 | |

| Decided medicines were not needed | 1.2 [0.2, 8.1] | 2.4 [0.3, 15.9] | 0 | 0 | |

| Purchasing medication was not a priority | 1.2 [0.2, 8.1] | 2.4 [0.3, 15.9] | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 2.4 [0.6, 8.9] | 2.4 [0.3, 15.2] | 2.7 [0.4, 16.7] | 0 | |

CI, confidence interval.

Per cent of household index cases that received care at this facility type.

Per cent of household index cases prescribed medication.

Per cent of household index cases that did not obtain prescribed medication.

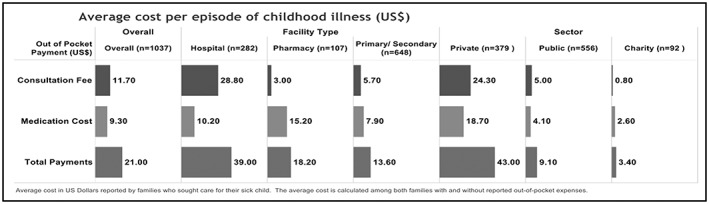

Spending on child health

Of the 1141 families with sick children needing care identified in the survey, 1037 (91%) sought care or treatment for their child (Table 4). Among the 1037 families that sought care, half (49.4%, confidence interval: 45.3–53.4) reported an out‐of‐pocket payment. The average total out‐of‐pocket cost per visit among all seeking care was $US21 ($US11.7 for consultations and $US9.3 for medications); however, the median cost per visit was $US0. There was a statistically significant difference in total out‐of‐pocket cost per visit by sector as follows: private facilities, $US43; public facilities, $US9.1 and NGO/charity facilities, $US3.4 (p < 0.001). Out‐of‐pocket payment amounts varied significantly by type of facility where care was sought, with the highest out‐of‐pocket payments reported in hospitals ($US39) versus $US18.2 for pharmacies and $US13.6 at primary/secondary level facilities (p = 0.002). Out‐of‐pocket payments were lower in the North region ($US15.0) than Central ($US25.1) and South ($US26.9); however, difference was only marginally significant (p = 0.063).

Table 4.

Out‐of‐pocket payments for consultation fees, medications and healthcare visit

|

Survey total Point 95 CI |

By region | By facility type* | By sector | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

North Point 95 CI |

Central Point 95 CI |

South Point 95 CI |

Primary/secondary Point 95 CI |

Hospital Point 95 CI |

Pharmacy Point 95 CI |

Public Point 95 CI |

Private Point 95 CI |

NGO/Charity Point 95 CI |

||

| Among all care seekers | n = 1037 | n = 506 | n = 474 | n = 57 | n = 648 | n = 282 | n = 107 | n = 566 | n = 379 | n = 92 |

| Total costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 8.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 0 | 22.6 | 0 |

| Mean | 21.0 [16.0, 26.0] | 15.0 [10.8, 19.2] | 26.9 [18.0, 35.8] | 25.1 [−5.8, 55.9] | 13.6 [11.3, 15.9] | 39.0 [22.3, 55.6] | 18.2 [13.6, 22.8] | 9.1 [5.4, 12.8] | 43.0 [31.1, 55.0] | 3.4 [1.9, 5.0] |

| Consultation costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.1 | 0 |

| Mean | 11.7 [7.4, 16.0] | 7.5 [4.2, 10.9] | 15.2 [7.4, 22.9] | 19.6 [−9.5, 48.7] | 5.7 [4.5, 6.9] | 28.8 [13.3, 44.2] | 3.0 [0.2, 5.8] | 5.0 [1.7, 8.3] | 24.3 [13.5, 35.2] | 0.8 [0.3, 1.4] |

| Medication costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 0 | 14.1 | 0 |

| Mean | 9.3 [8.0, 10.6] | 7.5 [5.9, 9.1] | 11.7 [9.6, 13.7] | 5.4 [2.4, 8.4] | 7.9 [6.6, 9.3] | 10.2 [7.8, 12.6] | 15.2 [12.2, 18.2] | 4.1 [3.1, 5.1] | 18.7 [16.4, 21.1] | 2.6 [1.2, 4.0] |

| Among care seekers with any payment | n = 508 | n = 207 | n = 276 | n = 25 | n = 283 | n = 124 | n = 101 | n = 137 | n = 345 | n = 26 |

| Total costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 21.1 | 21.1 | 22.6 | 14 | 24 | 28.2 | 14.1 | 16.9 | 25.4 | 8.5 |

| Mean | 42.8 [33.5, 52.2] | 36.7 [28.0, 45.4] | 46.1 [31.5, 60.8] | 57.1 [−8.6, 122.9] | 31.2 [27.6, 34.7] | 88.6 [52.8, 124.5] | 19.3 [14.5, 24.1] | 37.5 [25.0, 49.9] | 47.3 [34.4, 60.1] | 12.2 [7.8, 16.6] |

| Consultation costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 5.6 | 7.1 | 5.6 | 0 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 0 | 0 | 7.1 | 1.4 |

| Mean | 23.9 [15.4, 32.3] | 18.4 [10.6, 26.2] | 26.1 [13.0, 39.2] | 44.7 [−18.4, 107.9] | 13.0 [10.8, 15.2] | 65.4 [31.5, 99.4] | 3.2 [0.2, 6.2] | 20.7 [8.4, 32.9] | 26.7 [14.9, 38.5] | 2.9 [1.0, 4.8] |

| Medication costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 8.5 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 5.6 |

| Mean | 19.0 [17.1, 20.9] | 18.3 [15.5, 21.0] | 20.1 [17.3, 22.8] | 12.4 [7.0, 17.8] | 18.1 [16.0, 20.2] | 23.2 [18.6, 27.8] | 16.1 [13.0, 19.2] | 16.8 [14.0, 19.6] | 20.6 [18.2, 23.0] | 9.3 [5.1, 13.5] |

| Among households paying for consultation | n = 296 | n = 121 | n = 164 | n = 11 | n = 217 | n = 68 | n = 11 | n = 44 | n = 237 | n = 15 |

| Consultation costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 28.2 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 14.1 | 2.8 |

| Mean | 41 [26.7, 55.3] | 31.5 [19.0, 44.0] | 43.9 [22.0, 65.7] | 101.6 [−40.2, 243.5] | 17.0 [14.5, 19.5] | 119.3 [61.8, 176.9] | 29.2 [10.0, 48.4] | 64.3 [30.2, 98.5] | 38.9 [22.3, 55.5] | 5.1 [2.3, 7.9] |

| Among households paying for medications | n = 453 | n = 182 | n = 250 | n = 21 | n = 251 | n = 102 | n = 100 | n = 121 | n = 314 | n = 18 |

| Medication costs | ||||||||||

| Median | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 11.3 | 14.1 | 21.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 9.9 |

| Mean | 21.3 [19.3, 23.2] | 20.8 [18.0, 23.6] | 22.2 [19.4, 24.9] | 14.8 [7.9, 21.6] | 20.5 [18.2, 22.7] | 28.2 [23.2, 33.2] | 16.3 [13.2, 19.3] | 19.0 [16.1, 22.0] | 22.6 [20.1, 25.1] | 13.4 [8.5, 18.3] |

All costs presented in $US.

Bold italic indicates statistically significant (p < 0.001) findings.

Bold indicates statistically significant (p < 0.50) findings.

CI, confidence interval; NGO, non‐governmental organization.

Private providers are included under primary/secondary and shops reported with pharmacies.

Details about the total and component costs of treatment (consultations and medications) are provided in Table 4 and Figure 3. Among the 1037 families who sought care for their sick child, 508 reported out‐of‐pocket payment for consultation, medication or both (Table 4). Among these families who paid for consultations and/or medications, the average total payment was $US42.8 ($US23.9 for consultations and $US19.0 for medications). The median values of these payments were as follows: total cost, $US21.1; consultation cost, $US5.6; and, medication cost, $US14.1. There were no statistically significant differences in costs across the three regions, type of facility or sector among paying families, but generally out‐of‐pocket payments were lowest in the North, in pharmacies and from NGO/Charity facilities.

Figure 3.

Average cost per episode of childhood ($US)

Among the 1037 families who sought care or treatment for their sick child, 296 reported paying for consultation, regardless of whether or not they paid for medications (Table 4). Among these 296 families who paid for consultations, the average and median cost per consultation was $US41 and $US14.1, respectively; there were statistically significant differences in average consultation cost across regions (p = 0.030) and types of facilities (p = 0.002). Average consultation cost in the South ($US101.6) was much higher than in the Central ($US43.9) and North ($US31.5) regions; however, the median value for all three regions was the same ($US14.1). The average consultation cost was $US119.3 at hospitals (median = $US28.2), $US29.2 at pharmacies (median = $US21.1) and $US17 at primary/secondary level facilities (median = $US14.1). Although the differences in average consultation costs among these 296 families was not statistically significant by sector (p = 0.188), there were large differences between the average consultation costs at public facilities ($US64.3) and private facilities ($US38.9), compared with NGO/charity facilities ($US5.1).

Among the 1037 families who sought care or treatment for their sick child, 453 reported paying for medications, regardless of whether or not they paid for a consultation (Table 4). Among these 453 families who paid for medications, the average cost per medication was $US21.3 (median = $US14.1). The differences in the average cost per medication (among paying families) were not statistically significant across the three regions (p = 0.839), the three types of health facilities (p = 0.291) or across the three sectors (p = 0.497).

Discussion

The most frequently reported cause of childhood illness among Syrian refugees in Jordan was respiratory problems, followed by fever, diarrhea, injury and skin problems. Injury was also a common reason for seeking care accounting for 6.1% of consultations. The burden of conflict‐related injuries is high in this population, but it is possible that many of these are also related to unintentional injury in and around the home. More information should be sought to better understand the causes of injury in this population and appropriate interventions designed.

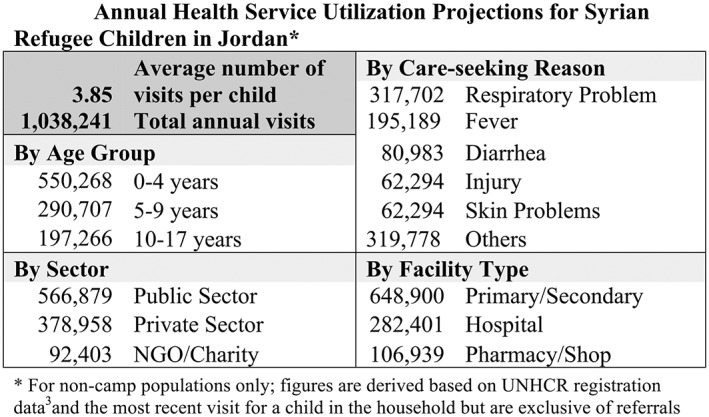

More than 90% of families who reported needing care for their sick child received care. If we extrapolate the reported care seeking among the survey sample, we estimate an average of 3.85 visits per child per year (Figure 4). This value is within the range of 2 to 4 provided by SPHERE standards and suggests relatively good access to care for sick children among Syrian refugees in Jordan (Sphere Project, 2011). Given the survey findings, we estimate that the increased burden on the Jordanian health system from sick child visits alone is more than 100 000 health visits per year including over 565 000 in the public sector (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Annual health service utilization projections for Syrian refugee children in Jordan.* NGO, non‐governmental organization

It is possible that many of the most frequently reported causes of sick child visits (respiratory problems, fever and diarrhea) are not from severe illness. A potential public health intervention would be to educate families to better discriminate when to seek care outside the home and to provide appropriate home management of minor childhood illness when indicated. This might be carried out through a variety of communication channels including community health volunteers and through providers at sites where Syrian families obtain services. About one‐half of families with sick children report paying either consultation or medication costs at an average cost of about $US21 per illness episode and an average of about $US43 among families who reported paying something. Both the Jordanian health system and refugee families would benefit from more rational care seeking and appropriate home management of childhood illness.

A large proportion of Syrians (36.5%) sought care for their children in the private sector even though total out‐of‐pocket cost per visit was significantly higher in private facilities (more than four times that of public facilities and more than 10 times NGO/charity facilities). More information is needed on why the private sector is being utilized by a large proportion of refugees when more cost‐effective options of a satisfactory standard are available. Significant savings could be made by families if they were to seek care at the public sector, NGOs and Islamic charity facilities.

The primary reason reported by families for not seeking care for their child when they believed it was needed was cost (68%). As mentioned earlier, many child health visits resulted in an out‐of‐pocket payment for the consultation and/or medication. This finding is more relevant today because health services for refugees now receive a lower subsidy than at the time of the survey—changes to Ministry of Public Health access policies for refugees in late 2014 have likely resulted in higher costs for refugees, which may have further reduced affordability of care (The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2015). Evidence from similar surveys conducted in 2014 and 2015 provides insight into the implications of this policy change. In the 2014 UNHCR health access and utilization survey, 4% of households needing care did not seek it compared with 13% in the 2015 survey, accompanying a measured increase in average cost of care from $US32 per visit in 2014 to $US46 in 2015. Similar to this study, the main barrier to care was cost of care in both prior surveys (UNHCR, 2015e, 2014). This has been even more critical now that most Syrian families in Jordan no longer have access to the full food voucher support and are exhausting their savings and other coping strategies. We raise the question of how the humanitarian community will ensure access to care given a future that portends further funding shortfalls.

Limitations

With respect to sampling, reliance on United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) registration data may have resulted in sampling bias if the geographic distribution of registered and unregistered households differed; 95% of households in the survey reported being registered with UNHCR. The within‐cluster referral process also presents potential for bias, as respondents may not have always referred to the nearest household; referral procedures and small clusters size may have attenuated within‐cluster similarities and the associated design effect. Replacement sampling, which was carried out for logistical purposes, also could contribute to bias if there are systematic differences between households that were and were not at home. Finally, interviews were conducted by Jordanians that could have resulted in a higher refusal rate, hesitance or influence on the part of Syrian refugees in responding to certain questions than if interviews had been conducted by Syrians.

Conclusions

Syrian refugees had good access to care for their sick children at the time of the survey. And given the number of refugees in Jordan, this level of access to care has resulted in a very large burden on the health system in particular the public health system. Access to care is likely to have deteriorated since the survey because of lower levels of subsidies to health facilities for serving Syrian refugees. The Jordanian government will require additional support to increase and maintain levels of access. In addition, public health promotion activities would help to better rationalize care and reduce out‐of‐pocket expenses among Syrian families who have settled in Jordan.

Author Contributions

SD led the design of the study and preparation of the manuscript; EL oversaw data collection, led data analysis and contributed to preparation of the manuscript; LA oversaw data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript; AB contributed to the design of the study, preparation of the manuscript and critical review of the manuscript; and WW AB contributed to the design of the study, data analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study was implemented by The Center for Refugee and Disaster Response at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (JHSPH) and The School of Nursing at Jordan University for Science and Technology (JUST). Technical support was provided by the UNHCR, the WHO and the Ministry of Health (MoH) of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The study team would like to acknowledge Timothy Roberton, Tyler Alvare and Gilbert Burnham from JHSPH for their many contributions to study design and implementation. We also extended our gratitude to Dr. Arwa Oweis and the JUST interviewers, without whom this work would not have been possible. Finally, we would like to acknowledge Rick Brennan, Claudine Prudhon, Altaf Musani, Basel Al‐Yousfi, Miranda Shami, Mary Sweidan and Said Aden from WHO and Paul Spiegel and Marian Schilperoord from the UNHCR for their support and efforts to facilitate the survey.

The authors have no competing interests.

Doocy, S. , Lyles, E. , Akhu‐Zaheya, L. , Burton, A. , and Weiss, W. (2016) Health service utilization and access to medicines among Syrian refugee children in Jordan. Int J Health Plann Mgmt, 31: 97–112. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2336.

References

- Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS) . 2014. Regional analysis Syria: part II—host countries. Available at: http://www.acaps.org/reports/downloader/part_ii_host_countries_july_2014/90/syria, accessed 12 June 2015.

- Guha‐Sapir D, Panhuis WG. 2004. Conflict‐related mortality: an analysis of 37 datasets. Disasters 28: 418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierres A, Spiegel P. 2012. The state of the world's refugees: adapting health responses to urban environments. JAMA 308(7): 673–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshidi MM, Hijjawi MQB, Jeriesat S, Eltom A. 2013. Syrian refugees and Jordan's health sector. Lancet 382(9888): 206–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sphere Project . 2011. Sphere handbook: humanitarian charter and minimum standards in disaster response. P. 297 Available at: http://www.sphereproject.org/content/view/720/200/lang, English, accessed 29 September 2015.

- Spiegel P. 2010. Public health and HIV section at UNHCR. Urban refugee health: meeting the challenges. Forced Migr Rev 34: [Google Scholar]

- The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation . 2015. Jordan response plan for the Syria crisis. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2ulC5rjYSncTi1PUC03M01sMGM/view, accessed 29 September 2015.

- The New York Times . 2015. Funding shortfalls for Syrian refugees in 5 host countries. May 19, 2015. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2015/05/19/us/ap‐ml‐syrian‐refugees‐glance.html?_r=0, accessed 17 June 2015.

- Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. 1990. Prevention of excess mortality in refugee and displaced populations in developing countries. JAMA 263: 3296–3302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. 1997. The public health aspects of complex emergencies and refugee situations. Annu Rev Public Health 18: 283–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR . 2015b. External statistical report on active registered Syrians in Jordan. Available at: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=8714, accessed 12 June 2015d.

- UNHCR . 2015b. UNHCR global trends: forced displacement in 2014. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/556725e69.html, accessed 19 June 2015.

- UNHCR . 2015c. Syria regional response. Available at: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php, accessed 15 June 2015.

- UNHCR . 2015d. Syria regional response: Jordan. Available at: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=107, accessed 15 June 2015a.

- UNHCR . 2015e. At a glance: health access and utilization survey among non‐camp refugees in Jordan. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/JordanHAUS2015FINALReport‐2.pdf, accessed 29 September 2015.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) . 2014. Health access and utilisation survey among non‐camp Syrian refugees. Available at: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=6029, accessed 29 September 2015.

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) . 2015. Syrian children under siege. Available at: http://www.unicefusa.org/mission/emergencies/conflict/syria, accessed 18 June 2015.