Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess behavioural recovery from the patient's perspective as a prespecified secondary outcome in a multicentre parallel‐group randomized clinical trial comparing ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and surgery for the treatment of primary varicose veins.

Methods

Participants were recruited from 11 UK sites as part of the CLASS trial, a randomized trial of UGFS, EVLA or surgery for varicose veins. Patients were followed up 6 weeks after treatment and asked to complete the Behavioural Recovery After treatment for Varicose Veins (BRAVVO) questionnaire. This is a 15‐item instrument that covers eight activity behaviours (tasks or actions an individual is capable of doing in an idealized situation) and seven participation behaviours (what the individual does in an everyday, real‐world situation) that were identified to be important from the patient's perspective.

Results

A total of 798 participants were recruited. Both UGFS and EVLA resulted in a significantly quicker recovery compared with surgery for 13 of the 15 behaviours assessed. UGFS was superior to EVLA in terms of return to full‐time work (hazard ratio 1·43, 95 per cent c.i. 1·11 to 1·85), looking after children (1·45, 1·04 to 2·02) and walks of short (1·48, 1·19 to 1·84) and longer (1·32, 1·05 to 1·66) duration.

Conclusion

Both UGFS and EVLA resulted in more rapid recovery than surgery, and UGFS was superior to EVLA for one‐quarter of the behaviours assessed. The BRAVVO questionnaire has the potential to provide important meaningful information to patients about their early recovery and what they may expect to be able to achieve after treatment.

Short abstract

BRAVVO questionnaire provides important recovery information

Introduction

Minimally invasive treatments for varicose veins such as ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) and thermal ablation techniques have become widely used alternatives to surgery for the treatment of varicose veins. One of the advantages of these techniques is the reported quicker return to normal activities, particularly following UGFS1, 2, 3. However, it is unclear whether thermal ablation, in particular endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), is also associated with a clinically significant quicker return to normal activities compared with surgery; some studies4, 5 have shown an earlier return and others2, 6, 7, 8 no difference.

Until recently, there was no standard means of assessing recovery from the patient's perspective. This led to the use of varying definitions such as return to ‘normal activities’, ‘full activity’, ‘daily activity’ or ‘basic physical activities’ and/or ‘return to work’ in previous studies. This lack of standardization led the authors to develop a 15‐item questionnaire to assess distinct aspects of normal activities that were identified as important by patients9 – the Behavioural Recovery After treatment for Varicose Veins (BRAVVO) questionnaire.

This paper reports behavioural recovery results from a multicentre parallel‐group randomized clinical trial (CLASS, Comparison of LAser, Surgery and foam Sclerotherapy) that compared the clinical efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of three treatment modalities: UGFS, EVLA with delayed foam sclerotherapy to residual varicosities if required, and surgery. Behavioural recovery was one of the prespecified secondary outcomes of the CLASS trial. The clinical and cost‐effectiveness results have been reported elsewhere10, 11.

Methods

Patients were recruited from 11 centres in the UK between November 2008 and October 2012. This study (ISRCTN51995477) had research ethics committee and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority approval. Eight centres randomized participants to one of three treatment options, and three centres offered only UGFS and surgery. Participants were randomized between the treatments with even allocation, using a minimization algorithm that included centre, age (less than 50 years, 50 years or more), sex, great saphenous vein (GSV) or small saphenous vein (SSV) reflux, and unilateral or bilateral disease. Inclusion criteria were: age over 18 years; primary unilateral or bilateral symptomatic varicose veins (Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiological (CEAP) grade C2 or above); GSV and/or SSV involvement; and reflux exceeding 1 s on duplex ultrasonography. Exclusion criteria were: current deep vein thrombosis; acute superficial vein thrombosis; a GSV or SSV diameter smaller than 3 mm or larger than 15 mm; tortuous veins considered unsuitable for EVLA or stripping; and contraindications to UGFS or to general/regional anaesthesia that would be required for surgery.

Treatments

The treatments have been described in detail elsewhere9, 10. For UGFS, foam was produced using the Tessari technique12 using a ratio of 0·5 ml sodium tetradecyl sulphate to 1·5 ml air (3 per cent for GSV/SSV truncal veins, 1 per cent for varicosities; maximum 12 ml foam per session). EVLA of GSVs/SSVs was performed under local anaesthetic, and patients were offered UGFS to any residual varicosities at 6‐week follow‐up if required, with the exception of one centre that performed concurrent phlebectomies. Surgery in the form of proximal GSV/SSV ligation and stripping (all GSV) and concurrent phlebectomies was performed under general or regional anaesthetic as a day‐case procedure. Compression stockings were applied after all three treatments.

Post‐treatment activity

All participants were given a study patient information leaflet (PIL), which recommended a return to all normal activities as soon as they were able, but that strenuous activity/contact sport should be avoided for 1–2 weeks. The PIL specifically stated that following EVLA or UGFS ‘most people are able to return to work within 2–3 days of treatment, but some people go back the following day or even the same day’, and that following surgery ‘people can return to office or sedentary work after 2–3 days; and that most people will be back at work within a week after surgery to one leg and 2 weeks after surgery to both legs; but there is no reason to remain off work as long if it can be managed with reasonable comfort’. Participants undergoing UGFS or EVLA were advised to wear compression stocking for 10 days constantly (day and night). Those in the surgery group were advised that bandages would be removed the day after operation, following which they should wear a stocking for 10 days, but that it was reasonable to remove the stocking after 4 or 5 days, providing that they were active.

Data collection

The participants were asked to complete the BRAVVO questionnaire along with other study questionnaires (Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire, EQ‐5D™ (EuroQoL, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) and Short Form 36 (QualityMetric, Lincoln, Rhode Island, USA)) at the 6‐week follow‐up appointment. Participants who failed to attend the 6‐week appointment were sent the questionnaire to complete at home.

The BRAVVO questionnaire was developed as an instrument to assess the activity and participation components of the World Health Organization International Classification of Disability and Function model13. Variation in activity and participation is not fully explained by impairment and so these constructs are important additional indicators of health outcome. An interview study involving 17 patients who had recently undergone varicose vein treatment was carried out to identify normal activities and ‘milestone’ behaviours to incorporate into the questionnaire. In addition to sampling from the three treatment options, diversity sampling was used in an attempt to gain a mix of sex, age and rural–urban location. Seventeen interview transcripts were content‐analysed in four stages to identify appropriate items to include in a questionnaire. Full details of this process have been published previously9.

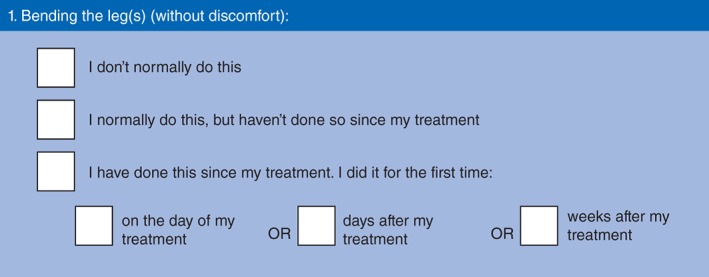

The BRAVVO questionnaire assesses the time taken for patients to return to performing 15 behaviours: eight ‘activity’ behaviours (tasks or actions an individual is capable of doing in an idealized situation) and seven ‘participation’ behaviours (what the individual does in an everyday, real‐world situation) that were identified to be important from the patient's perspective9. Fig. 1 shows the question layout.

Figure 1.

Question layout

Statistical analysis

Data from the BRAVVO questionnaire were analysed within an interval‐censored time‐to‐event framework using flexible parametric survival models14. For each behaviour item, each participant's response was converted into the number of days to return to that behaviour. If a participant indicated that return to the behaviour was on the day of the procedure, this was assumed to be interval‐censored between day 0 and day 1. If a participant indicated return to the behaviour was after a number of weeks, not days, this was assumed to be interval‐censored between the previous week and the week indicated. For example, if a participant reported 5 weeks, it was assumed that the return to the behaviour took place between 28 and 35 days. A participant who indicated that they had not returned to a behaviour that they usually performed was right‐censored at 42 days. Participants who indicated that they did not normally perform a specific behaviour were not included in analysis of that behaviour. No missing data were imputed.

Data are reported as the number of days for 50 and 90 per cent of participants to return to each behaviour, estimated from the parametric survival models (the 50 per cent value represents the median time to return to this behaviour). Extrapolation beyond the 42‐day cut‐off was performed for behaviours where 90 per cent of participants had not returned to the behaviour by 42 days. Treatment effects are presented as hazard ratios with associated 95 per cent c.i. All analyses were carried out in Stata® 1215. Flexible parametric survival models were fitted using the stpm package16.

Results

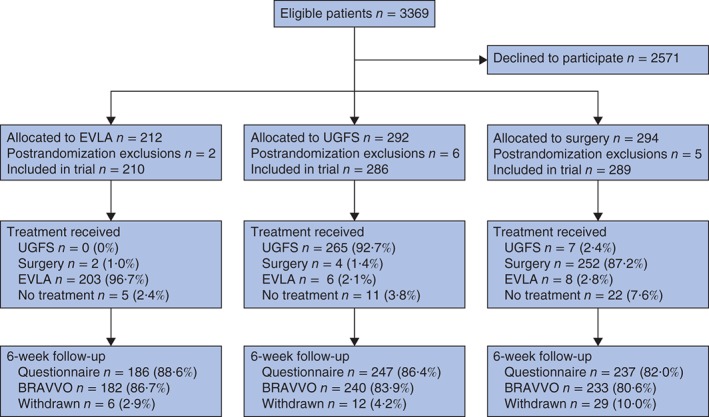

Seven hundred and ninety‐eight participants were recruited, of whom 13 were ineligible (for example because they had recurrent veins or veins larger than 15 mm in diameter) after randomization and were considered postrandomization exclusions (Fig. 2). The groups were well balanced in terms of demographic characteristics at baseline, but there was an increased incidence of deep venous reflux in the foam group compared with the surgery group (P = 0·005) (Table 1). Of the 670 participants who completed the 6‐week questionnaire, 655 completed at least one of the BRAVVO questions. Completion rates were slightly lower for the questions about going out socially (74·8 per cent) and sporting activity (66·0 per cent), which may not have been relevant to all participants. For all behaviours, except wearing clothes that show the leg, going out socially and sporting activities, over 95 per cent of participants had returned to normal behaviour within 6 weeks of intervention.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram for the trial. Reasons for postrandomization exclusion included: recurrent varicose veins and veins larger than 15 mm. Reasons for withdrawal from follow‐up included: patient decided not to proceed with treatment (and also declined follow‐up), declined follow‐up after treatment or did not wish to complete questionnaires. UGFS, ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy; EVLA, endovenous laser ablation

Table 1.

Demographic details at recruitment

| EVLA | UGFS | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 210) | (n = 286) | (n = 289) | |

| Age (years)* | 49·7 (18–80) | 49·0 (19–78) | 49·2 (22–85) |

| Sex ratio (F : M) | 120 : 90 | 162 : 124 | 163 : 126 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | 27·0 (17–42) | 27·1 (17–44) | 27·7 (17–44) |

| Unilateral disease | 153 (72·9) | 215 (75·2) | 196 (67·8) |

| Employment status | |||

| Self‐employed | 21 (10·2) | 37 (13·0) | 29 (10·3) |

| Employed | 120 (58·3) | 169 (59·3) | 179 (63·5) |

| Other | 65 (31·6) | 79 (27·7) | 74 (26·2) |

| Unknown | 4 | 1 | 7 |

| Saphenous vein involvement | |||

| Great saphenous | 182 (86·7) | 232 (81·1) | 239 (82·7) |

| Small saphenous | 14 (6·7) | 21 (7·3) | 21 (7·3) |

| Great and small saphenous | 14 (6·7) | 33 (11·5) | 29 (10·0) |

| Deep vein reflux | 28 of 205 (13·7) | 47 of 280 (16·8) | 25 of 282 (8·9) |

| CEAP classification | |||

| C2, varicose veins over 3 mm | 113 (54·1) | 169 (59·1) | 147 (51·2) |

| C3, oedema | 28 (13·4) | 35 (12·2) | 39 (13·6) |

| C4, skin/subcutaneous changes | 56 (26·8) | 74 (25·9) | 90 (31·4) |

| C5/C6, healed/active venous ulcer | 12 (5·7) | 8 (2·8) | 11 (3·8) |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean (range). EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; UGFS, ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy; CEAP, Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic.

Ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery

Participants randomized to UGFS recalled being able to carry out 13 of the 15 behaviours significantly more quickly than those randomized to surgery (Table 2 ). The two behaviours for which there was no evidence of a difference in the time to recover between the trial arms were ‘having a bath or shower’ and ‘wearing clothes that show the legs’. In general, the median time to return to the activity behaviours was 5 days or less for those randomized to UGFS and up to 9 days for those randomized to surgery. In both groups, there was greater variation in the median time to return to the participation behaviours than the activity behaviours.

Table 2.

Behavioural recovery: ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery

| Proportion carrying out behaviour (%) | Time until specified proportion of participants could carry out behaviour (days)* | Hazard ratio† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGFS | Surgery | |||

| Activity items | ||||

| Bending the legs without discomfort | 50 | 3·0 | 4·6 | 1·38 (1·14, 1·67) |

| 90 | 14·1 | 21·3 | ||

| Lifting heavy objects without discomfort | 50 | 4·8 | 9·8 | 1·97 (1·59, 2·44) |

| 90 | 16·9 | 34·5 | ||

| Moving from standing to sitting without discomfort | 50 | 1·9 | 3·7 | 1·63 (1·35, 1·97) |

| 90 | 9·3 | 17·5 | ||

| Standing still for a long time (> 15 min ) without discomfort | 50 | 3·9 | 7·1 | 1·67 (1·36, 2·05) |

| 90 | 15·8 | 28·7 | ||

| Walking short distances (< 20 min ) without discomfort | 50 | 1·9 | 4·4 | 2·00 (1·65, 2·42) |

| 90 | 8·2 | 19·1 | ||

| Walking long distances (> 20 min) | 50 | 4·5 | 8·0 | 1·76 (1·45, 2·14) |

| 90 | 15·2 | 27·1 | ||

| Having a bath or shower | 50 | 5·4 | 4·9 | 0·85 (0·70, 1·03) |

| 90 | 11·4 | 10·3 | ||

| Driving a car | 50 | 4·1 | 7·0 | 1·78 (1·45, 2·19) |

| 90 | 12·4 | 21·1 | ||

| Participation items | ||||

| Doing housework | 50 | 2·1 | 4·5 | 2·10 (1·72, 2·56) |

| 90 | 7·3 | 15·7 | ||

| Looking after children | 50 | 1·2 | 3·5 | 2·20 (1·61, 3·00) |

| 90 | 6·2 | 17·9 | ||

| Wearing clothes that show the legs | 50 | 12·4 | 12·8 | 1·03 (0·78, 1·35) |

| 90 | 56·6 | 58·7 | ||

| Partial return to normal work/employment | 50 | 4·4 | 9·9 | 2·16 (1·72, 2·72) |

| 90 | 15·4 | 34·2 | ||

| Full return to normal work/employment | 50 | 4·8 | 11·7 | 2·56 (2·05, 3·21) |

| 90 | 14·9 | 36·2 | ||

| Going out socially | 50 | 7·1 | 9·3 | 1·29 (1·06, 1·57) |

| 90 | 25·8 | 34·0 | ||

| Sporting activity or exercise | 50 | 15·7 | 21·8 | 1·33 (1·05, 1·68) |

| 90 | 62·6 | 86·7 | ||

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i.

The 50 per cent value is equivalent to the median time to return to the behaviour.

A hazard ratio greater than 1·00 shows that return to the behaviour took longer in the surgery arm. UGFS, ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy.

Endovenous laser ablation versus surgery

Participants randomized to EVLA recalled being able to carry out 13 of the 15 behaviours significantly more quickly than those randomized to surgery (Table 3). Return to ‘having a bath or shower’ was quicker after surgery than after EVLA. There was no difference in time to return to the participation behaviour of ‘wearing clothes that show the legs’.

Table 3.

Behavioural recovery: endovenous laser ablation versus surgery

| Proportion carrying out behaviour (%) | Time until specified proportion of participants could carry out behaviour (days)* | Hazard ratio† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVLA | Surgery | |||

| Activity items | ||||

| Bending the legs without discomfort | 50 | 2·7 | 4·6 | 1·49 (1·19, 1·75) |

| 90 | 12·6 | 21·3 | ||

| Lifting heavy objects without discomfort | 50 | 5·9 | 9·8 | 1·79 (1·39, 2·27) |

| 90 | 20·5 | 34·5 | ||

| Moving from standing to sitting without discomfort | 50 | 2·2 | 3·7 | 1·56 (1·27, 1·96) |

| 90 | 10·4 | 17·5 | ||

| Standing still for a long time (> 15 min) without discomfort | 50 | 4·8 | 7·1 | 1·41 (1·11, 1·79) |

| 90 | 20·0 | 28·7 | ||

| Walking short distances (< 20 min) without discomfort | 50 | 3·0 | 4·4 | 1·30 (1·04, 1·61) |

| 90 | 13·2 | 19·1 | ||

| Walking long distances (> 20 min) | 50 | 5·6 | 8·0 | 1·53 (1·06, 1·67) |

| 90 | 19·8 | 27·1 | ||

| Having a bath or shower | 50 | 5·5 | 4·9 | 0·74 (0·59, 0·93) |

| 90 | 12·8 | 10·3 | ||

| Driving a car | 50 | 4·4 | 7·0 | 1·82 (1·43, 2·33) |

| 90 | 12·7 | 21·1 | ||

| Participation items | ||||

| Doing housework | 50 | 2·5 | 4·5 | 1·89 (1·49, 2·38) |

| 90 | 8·4 | 15·7 | ||

| Looking after children | 50 | 1·9 | 3·5 | 1·61 (1·15, 2·27) |

| 90 | 8·8 | 17·9 | ||

| Wearing clothes that show the legs | 50 | 14·6 | 12·8 | 0·97 (0·69, 1·35) |

| 90 | 75·1 | 58·7 | ||

| Partial return to normal work/employment | 50 | 6·3 | 9·9 | 1·75 (1·33, 2·27) |

| 90 | 21·1 | 34·2 | ||

| Full return to normal work/employment | 50 | 7·7 | 11·7 | 1·79 (1·37, 2·27) |

| 90 | 23·5 | 36·2 | ||

| Going out socially | 50 | 6·9 | 9·3 | 1·41 (1·12, 1·75) |

| 90 | 23·9 | 34·0 | ||

| Sporting activity or exercise | 50 | 14·2 | 21·8 | 1·47 (1·12, 1·92) |

| 90 | 55·5 | 86·7 | ||

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i.

The 50 per cent value is equivalent to the median time to return to the behaviour.

A hazard ratio greater than 1·00 shows that return to the behaviour took longer in the surgery arm. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation.

Endovenous laser ablation versus ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy

There were no differences in the time taken to return to 11 of the 15 behaviours between participants randomized to EVLA and those randomized to UGFS (Table 4). Return to ‘walking short distances without discomfort’, ‘walking long distances’, ‘looking after children’ and ‘full return to normal work/employment’ took longer for the EVLA group than the UGFS group. Following UGFS or EVLA only one‐third of the specific behaviours could be carried out by 50 per cent of participants by 3 days after treatment.

Table 4.

Behavioural recovery: endovenous laser ablation versus ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy

| Proportion carrying out behaviour (%) | Time until specified proportion of participants can carry out behaviour (days)* | Hazard ratio† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVLA | UGFS | |||

| Activity items | ||||

| Bending the legs without discomfort | 50 | 2·7 | 3·0 | 0·94 (0·75, 1·17) |

| 90 | 12·6 | 14·1 | ||

| Lifting heavy objects without discomfort | 50 | 5·9 | 4·8 | 1·11 (0·87, 1·42) |

| 90 | 20·5 | 16·9 | ||

| Moving from standing to sitting without discomfort | 50 | 2·2 | 1·9 | 1·12 (0·90, 1·40) |

| 90 | 10·4 | 9·3 | ||

| Standing still for a long time (> 15 min) without discomfort | 50 | 4·8 | 3·9 | 1·14 (0·90, 1·44) |

| 90 | 20·0 | 15·8 | ||

| Walking short distances (< 20 min) without discomfort | 50 | 3·0 | 1·9 | 1·48 (1·19, 1·84) |

| 90 | 13·2 | 8·2 | ||

| Walking long distances (> 20 min) | 50 | 5·6 | 4·5 | 1·32 (1·05, 1·66) |

| 90 | 19·8 | 15·2 | ||

| Having a bath or shower | 50 | 5·5 | 5·4 | 1·19 (0·96, 1·48) |

| 90 | 12·8 | 11·4 | ||

| Driving a car | 50 | 4·4 | 4·1 | 0·95 (0·74, 1·21) |

| 90 | 12·7 | 12·4 | ||

| Participation items | ||||

| Doing housework | 50 | 2·5 | 2·1 | 1·03 (0·82, 1·29) |

| 90 | 8·4 | 7·3 | ||

| Looking after children | 50 | 1·9 | 1·2 | 1·45 (1·04, 2·02) |

| 90 | 8·8 | 6·2 | ||

| Wearing clothes that show the legs | 50 | 14·6 | 12·4 | 1·17 (0·83, 1·64) |

| 90 | 75·1 | 56·6 | ||

| Partial return to normal work/employment | 50 | 6·3 | 4·4 | 1·17 (0·89, 1·52) |

| 90 | 21·1 | 15·4 | ||

| Full return to normal work/employment | 50 | 7·7 | 4·8 | 1·43 (1·11, 1·85) |

| 90 | 23·5 | 14·9 | ||

| Going out socially | 50 | 6·9 | 7·1 | 0·88 (0·70, 1·10) |

| 90 | 23·9 | 25·8 | ||

| Sporting activity or exercise | 50 | 14·2 | 15·7 | 0·80 (0·61, 1·04) |

| 90 | 55·5 | 62·6 | ||

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i.

The 50 per cent value is equivalent to the median time to return to the behaviour.

A hazard ratio greater than 1·00 shows that return to the behaviour took longer in the endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) arm. UGFS, ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy.

Discussion

This study showed that both UGFS and EVLA resulted in a more rapid recovery compared with surgery for 13 of the 15 behaviours. UGFS was superior to EVLA in terms of return to full time work, looking after children and walking (both short and long distances). Importantly, the specific behaviours assessed were shown to have a range of different recovery trajectories.

Previous randomized clinical trials showed behavioural recovery to be more rapid following UGFS compared with surgery1, 2, but the benefit of EVLA over surgery was less clear2, 4, 8 . In this study, for all but two behaviours (wearing clothes that showed the legs and showering/bathing) the recovery was quicker following UGFS or EVLA compared with surgery. These findings may have arisen as a result of information contained in the study PIL, which recommended that compression hosiery was worn continuously for 10 days following UGFS or EVLA but for 4–5 days routinely after surgery.

In the comparison between UGFS and EVLA, behavioural recovery was faster following UGFS for four of the 15 behaviours; there was no difference between the groups for the other behaviours. Two previous randomized trials2, 3 showed earlier return to ‘normal activities’ in patients undergoing UGFS compared with EVLA. Specifically, the present study showed a quicker return to full‐time work following UGFS, similar to the findings of Rasmussen and colleagues2. The median time taken to return to work following EVLA (7·7 days) was within the ranges reported2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. However, Rasmussen and colleagues2 reported earlier return to work after UGFS compared with the present study (median 2·9 versus 4·8 days respectively). A partial explanation of the difference between the two studies may be that, unlike the previous study, the present analysis did not correct for weekends.

For other behaviours, the recalled recovery times following both UGFS and EVLA were longer than might be expected from the literature2, 3, 4, 5, 8. This may be explained by the timing of the questionnaire at 6 weeks, and thus it is the nature of the differences between treatment groups rather than the absolute timings taken to return to these activities that the authors wish to highlight in this paper.

The extent of this overall delay in recovery is hard to justify, particularly in light of the standard information and advice given in the study PIL. There may have been a number of external influences affecting participants' recollection of their recovery, including misinformation and fear. Although attitudes to recovery and return to normal behaviours have changed in secondary care, this may not have filtered into primary care or ‘public knowledge’. Fear of activity or fear of pain caused by activity has been documented following surgery for other conditions17, 18. It is possible that some people undergoing treatment for varicose veins experience similar fears, and this may limit or restrict their activity following treatment. With regard to return to work, there are clearly a number of additional factors that might play a role, such as a person's employment status (employed or self‐employed), the sickness benefits they are entitled to, the type of work they are employed to do, how long they are ‘signed off’ by the doctor, and the views of their employer on return to work after an operation. It should be noted that this study distinguished between partial and full return to work, and that no difference was noted in partial return to work following UGFS and EVLA. This finding may be of substantial importance to patients, their employers and the economy as a whole.

The main strength of this study is that the behaviours investigated were based on systematic investigation of the recovery milestones that are important to patients following treatment for varicose veins. Hence, the findings are of personal importance from a patient perspective. Distinguishing between the behaviours that contribute to ‘normal activity’ helps build a profile of recovery that may be particularly useful for patients preparing for, or recovering from, treatment. Furthermore, the methodology used to develop the BRAVVO questionnaire could be used in other conditions to provide normative information about behavioural recovery that is relevant to patients. The BRAVVO questionnaire was pilot tested and found to be acceptable to patients, comprehensible and appropriate for self‐completion. Despite this, a potential weakness of the study is that the level of missing data in the BRAVVO questionnaire was higher for two of the questions. Further work to reformat or rephrase the questions or response options may help minimize levels of missing data. A further potential weakness is the choice of assessment time point (6 weeks after treatment). This may have compromised recall, particularly for behaviours that participants were able to return to a short time after treatment; however, any compromise in recall is likely to have affected the three treatment groups equally. Other study outcomes were assessed at 6 weeks, and behavioural recovery was assessed at the same time point to minimize participant burden. Further work is required to determine the optimal timing(s) of this questionnaire. Given that the median time to return to the behaviour was less than 14 days for 13 of the behaviours, and up to 22 days for the other two (wearing clothes that show the legs, sporting activity or exercise), the use of the questionnaire at approximately 2–3 weeks would seem appropriate.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Cruden for secretarial support and data management; G. McPherson and the programming team at the Centre for Healthcare Randomized Trials; members of the Project Management Group for their ongoing advice and support of the trial; D. Bolsover, who contributed to the development of the BRAVVO questionnaire; the independent members of the Trial Steering Committee (A. Davies (Chair), I. Loftus, J. Nixon) and Data Monitoring Committee (G. Stansby (Chair), W. Banya, M. Flather); and the staff at recruitment sites who facilitated recruitment, treatment and follow‐up of trial participants.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme (project number 06/45/02). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, National Health Service or the Department of Health. The Health Services Research Unit is funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorate.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Wright D, Gobin JP, Bradbury A, Coleridge‐Smith P, Spoelstra H, Berridge D et al Varisolve polidocanol microfoam compared with surgery or sclerotherapy in the management of varicose veins in the presence of trunk vein incompetence: European randomised controlled trial. Phlebology 2006; 21: 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rasmussen LH, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Vennits B, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomised clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 1079–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lattimer CR, Azzam M, Kalodiki E, Shawish E, Trueman P, Geroulakos G. Cost and effectiveness of laser with phlebectomies compared with foam sclerotherapy in superficial venous insufficiency. Early results of a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 43: 594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Samuel N, Carradice D, Wallace T, Mekako A, Hatfield J, Chetter I. Randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser therapy versus conventional surgery for short saphenous varicose veins. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darwood RJ, Theivacumar N, Dellagrammaticas D, Mavor AI, Gough MJ. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with surgery for the treatment of primary great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2008; 95: 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rasmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, Blemings A, Lawaetz B, Eklof B. Randomised trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with high ligation and stripping in patients with varicose veins: short‐term results. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pronk P, Gauw SA, Mooij MC, Gaastra MT, Lawson JA, van Goethem AR et al Randomised controlled trial comparing sapheno‐femoral ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein with endovenous laser ablation (980nm) using local tumescent anaesthesia: one year results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 40: 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rass K, Frings N, Glowacki P, Hamsch C, Graber S, Vogt T et al Comparable effectiveness of endovenous laser ablation and high ligation with stripping of the great saphenous vein: two‐year results of a randomized clinical trial (RELACS study). Arch Dermatol 2012; 148: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, Tassie E, Scotland G, Ramsay CR et al Clinical and cost‐effectiveness of foam sclerotherapy, endovenous laser ablation and surgery for varicose veins: results from the Comparison of LAser, Surgery and foam Sclerotherapy (CLASS) randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2015; 19: 1–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, Ramsay CR, Norrie J, Burr J et al A randomized trial comparing treatments for varicose veins. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tassie E, Scotland G, Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, Campbell MK et al. Cost‐effectiveness of ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy, endovenous laser ablation or surgery as treatment for primary varicose veins from the randomised CLASS trial. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 1532–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tessari L, Cavezzi A, Frullini A. Preliminary experience with a new sclerosing foam in the treatment of varicose veins. Dermatol Surg 2001; 27: 58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [accessed 25 November 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Royston P, Parmar MK. Flexible proportional‐hazards and proportional‐odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Stat Med 2002; 21: 2175–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. StataCorp . Stata Multiple‐Imputation Reference Manual Release 12. StataCorp LP: College Station, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Royston P. Flexible alternatives to the Cox model, and more. Stata J 2001; 1: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross MD. The relationship between functional levels and fear‐avoidance beliefs following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Traumatol 2010; 11: 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear‐avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception – I. Behav Res Ther 1983; 21: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]