Abstract

Long-term exposure to arsenic has been linked to cancer in different organs and tissues, including skin. Here, non-malignant human keratinocytes (HaCaT) were exposed to arsenic and its effects on microRNAs (miRNAs; miR) expression were analyzed via miRCURY LNA array analyses. A total of 30 miRNAs were found differentially expressed in arsenic-treated cells, as compared to untreated controls. Among the up-regulated miRNAs, miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141, are well known to be involved in carcinogenesis. Additional findings confirmed that those three miRNAs were indeed up-regulated in arsenic-stimulated keratinocytes as demonstrated by quantitative PCR assay. Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis of both potential cancer-related pathways and targeted genes affected by miR-21, miR-200a and/or miR-141 was performed. Results revealed that miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 are implicated in skin carcinogenesis related with melanoma development. Conclusively, our results indicate that arsenic-treated keratinocytes exhibited alteration in the miRNAs expression profile and that miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 could be promising early biomarkers of the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells and they could be potential novel targets for melanoma therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Arsenite, cancer, carcinogenesis, miR-21, miR-200a, miR-141, miRNA-based cancer therapy, skin cancer

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to the metalloid arsenic around the world is a complex global environmental problem. Humans are frequently in contact to arsenic due that is a natural environmental pollutant of water, air, soil and food [1]. Arsenic is an element that occurs in the minerals surrounding aquatic underground reservoirs and it leaches to deposits that have been stored for prolonged time periods [2–4] resulting in extensive human exposure throughout the world. Several epidemiological studies have correlated the arsenic exposure with increases in the incidence of skin, liver, bladder, and lung cancer [5, 6]. This problem has been exacerbated by an increment in the use of arsenic contaminated water, especially in developing countries [7]. Moreover, melanoma is a skin cancer type that has an unfavorable prognosis and in developed countries is the main cause of death from skin cancers, with extensive influence of environmental factors to its etiology [8]. As one of the deadliest human cancers, malignant melanoma frequently conducts to death within a year, when it converts metastatic [9]. As a result, the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States, the European Union and the World Health Organization have adopted a 10 ppb limit for arsenic in drinking water and there are plans to reduce these limits to lower levels [10, 11]. For these reasons, there is a need to improve our knowledge of the molecular effects following arsenic exposure and its association with skin cancer, to reveal novel approaches for the design of melanoma therapeutic strategies.

MiRNAs are a big family of short single-stranded (~22 nucleotides) non-coding RNA molecules endogenously produced that are transcribed in animals, plants and some viruses, suppressing target gene translation by binding to their mRNA [12]. Also, miRNAs function as versatile gene expression regulators in virtually all cellular pathways in higher eukaryotes, including proliferation, apoptosis, cell differentiation, cell cycle, embryonic development and cellular disease [13, 14]. Additionally, miRNAs expression is altered in cancer emergence and metastatic occurrences, therefore having a pivotal role in health and disease [13]. The miRNAs family, grouping 1881 miRNAs sequences from Homo sapiens (hsa), is known to regulate the expression of more than 60% of human protein-coding genes [15–17]. Thus, miRNAs revealed an additional mechanism by which genes are regulated and added yet another dimension of complexity to the regulation of biological systems [18, 19]. The expression of miRNAs is affected by several toxicants and cellular stressors [20] and they can be used as novel biomarkers of toxicological insult [21].

Experimental manipulation has shown an important role of miRNAs as regulators in carcinogenesis and possibly in anti-cancer therapy [22]. For example, a recent study demonstrated that disturbing the expression of a single miRNA (miR-21) is sufficient to induce cancer in a mouse model [23]. Another experiment showed that restoring the expression of miR-26a in mice resulted in the significant size reduction of liver tumors without noticeable toxicity to healthy tissues [24]. Also, studies utilizing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) derived from epidermal keratinocyte indicates that miR-31 controls cancer-related phenotypes [25]. Moreover, it was revealed that miR-20a is involved in the tumor inhibition of CSCC [26]. Due to the role of miRNAs in cancer, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the functions of these small RNA molecules acting as gene regulators are disturbed by chemical carcinogens, such as arsenic. In this context, the investigation of miRNAs expression during arsenic exposure would open novel epigenetic perspectives to understand the toxicological effects derived by the presence of this cytotoxic metalloid in the environment, as well as in drinking water. It was proposed that more research is required to clarify the molecular mechanisms leading arsenic-driven carcinogenesis [27] and this study is a contribution to that type of endeavors, linking the miRNAs expression with skin carcinogenesis.

The non-tumorigenic human keratinocyte HaCaT cell line, at its full differentiation capacity [28], provides an excellent model to understand the effects of arsenic in the skin [29]. This cell line can be malignantly transformed after continuous exposure to low levels of sodium arsenite [30–32]. In the present study, HaCaT cells were used to investigate the effects of in-vitro arsenic exposure on miRNAs levels. We hypothesized that arsenite would disturb miRNAs expression in the HaCaT cells in connection with its other well-known genotoxic effects. The expression of miRNAs was investigated by using a specific Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) miRNA array. Our data demonstrated that human epithelial HaCaT cells differentially expressed miRNAs after lowconcentration sodium arsenite exposure and provided information about potential epigenetic markers of arsenic-driven skin carcinogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

The human keratinocyte HaCaT cell line (Cell Lines Service, Eppelheim, Germany) are spontaneously transformed to non-malignant keratinocytes that have been established from human male-derived skin cells [28, 33]. HaCaT cells exhibit a doubling time of approximately 24 hours [28]. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B. Consistently, cell cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Culture media was replaced with fresh growth media every 2–3 days. To ensure high cell viability, cells were processed as described earlier [34].

Arsenite Treatment

Aqueous solutions of sodium arsenite (NaAsO2, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; hereafter referred as arsenite) were prepared as concentrated stocks of 500 µM with sterile PBS (1000×), aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. HaCaT cells were seeded in eight flasks and grown to 80–90% confluence without arsenite. On the first day of exposure, cells from four flasks (control samples) were separately harvested by the use of 0.25% trypsin solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and stored in RNAlater RNA stabilization reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX) at −80 °C. The cells in the remaining four experimental flasks were then treated with medium containing 500 nM arsenite for a period of four weeks. During this period of time, at approximately 80–90% confluence level (~6–7 days), the cells were harvested with 0.25% Trypsin solution and a fraction (~150 000 cells) was seeded again to continue the arsenite exposure. As a consequence of the high dilution factor of the stock arsenite solution (1:1000), the final concentration of vehicle/solvent in the cell culture media was very low, 1 µl of PBS per 1 ml of growth media and therefore the vehicle control was omitted. At the end of this period, the cells in each of the four arsenite treated flasks were independently harvested and stored in RNAlater RNA stabilization solution at −80 °C. Four untreated control samples and four arsenite-treated samples were collected, each one representing a biological replicate.

Microarray Analysis

One control sample and one experimental sample were sent to the company Exiqon Inc. (Woburn, MA) in order to perform miRNA microarray hybridization and analysis. The miRCURY™ RNA Isolation Kit and the miRCURY™ LNA Array power labeling kit (Exiqon) were used to extract total RNA and to label the samples. The samples were then scanned using the Agilent G2565BA Microarray Scanner System (Santa Clara, CA) The ImaGene 8.0 software was used for image analysis (BioDiscovery, Inc., Hawthorne, CA). Normalization was performed with the global Lowess regression algorithm. The miRCURY™ LNA Array contains 1,890 capture probes that cover 1,395 human miRNAs (Exiqon Inc.).

MiRNAs Isolation and cDNA Preparation

In order to validate the microarray data, a miRNA purification kit (Biosynthesis, Lewisville TX) was used to extract miRNAs from the remaining biological replicates of the untreated control (N=3) and arsenite-treated (N=3) samples. Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized for each sample using the miRNA First-Strand synthesis kit following manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Briefly, 3.75 µl of miRNA sample were combined with 5 µl of mRQ Buffer (2×) and 1.25 µl of mRQ enzyme. The samples were incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C in a thermocycler and then, diluted with 90 µl of ddH2O.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

MiRNA primers, used to amplify their entire sequence, were designed for five selected miRNAs (Integrated DNA technologies Inc, Coralville, IA). The miRNAs expression was quantified using the SYBR qRT-PCR kit (Clontech) and the cDNA from each of the three biological replicates of arsenite-treated (N=3) and control samples (N=3). For each biological replicate the quantitative PCR (qPCR; real time PCR) assay was run in duplicates and miR-191 was used for normalization purposes, as recommended in the literature [35]. For data analysis, the fold change values were obtained by the delta-delta Ct (cycle threshold) method [36].

Potential Signaling Pathways and Target Genes

The DIANA-mirPath computational algorithm [37] was used to identify potential molecular pathways related to the three miRNAs whose differential expression was significantly overexpressed following qPCR analysis (miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141) as well as common gene targets of these miRNAs.

Statistical Analyses

Two-tailed paired Student's t-tests were accomplished to found the statistical significance of the differences between the mean values of experimental and control samples; arsenite-treated (N=3) vs. untreated (N=3) cells. Statistical significance was deemed for p values < 0.05.

RESULTS

Arsenic Exposure Caused Differential Expression of miRNAs

The microarray-based analysis showed thirty differentially expressed miRNAs in the miRNA samples from arsenite-treated HaCaT cells, as compared to the untreated controls (Table 1). Based on the fold change difference (cutoff expression value was of >1.5), twenty one of them were up-regulated and nine were down-regulated. The highest fold change difference was for miR-22 (2.43 fold) and the lowest for miR-PLUS-A1087 (0.33 fold). Some of the differentially expressed miRNAs are linked to carcinogenesis: miR-22 [38], miR-21, miR-34b [39], miR-141, miR-200a [40], miR-27b and miR-23b [41]. Six of the nine down-regulated miRNAs are denoted as miRPLUS. These six sequences are present in the miRCURY Exiqon array and are licensed human sequences that were not yet annotated in the miRBase at the time of the hybridization. These miRNAs were discovered by Exiqon which provided novel information about miRNAs that were not available in the literature.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed miRNAs in HaCaT cells after exposure to arsenite.

| miRNA | Fold Change |

miRNA | Fold Change |

miRNA | Fold Change* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-22† | 2.43 | hsa-miR-30e | 1.75 | hsa-miR-29b | 1.63 |

| hsa-miR-21 | 2.22 | hsa-miR-27b | 1.72 | hsa-miRPLUS-E1012 | 0.59 |

| hsa-miR-34a | 2.04 | hsa-miR-23b | 1.69 | hsa-miRPLUS-G1246-3p | 0.58 |

| hsa-miR-205 | 2.00 | hsa-miR-27a | 1.66 | hsa-miR-1285 | 0.57 |

| hsa-miR-141 | 1.92 | hsa-miR-1274a | 1.66 | hsa-miRPLUS-E1247 | 0.57 |

| hsa-miR-1260 | 1.92 | hsa-miR-181a | 1.66 | hsa-miRPLUS-F1147 | 0.56 |

| hsa-miR-720 | 1.88 | hsa-miR-1469 | 1.66 | hsa-miRPLUS-F1231 | 0.56 |

| hsa-miR-1280 | 1.85 | hsa-miR-19a | 1.63 | hsa-miR-34b | 0.56 |

| hsa-miR-200a | 1.81 | hsa-miR-184 | 1.63 | hsa-miR-F1017 | 0.49 |

| hsa-miR-19b | 1.78 | hsa-miR-101 | 1.63 | hsa-miRPLUS-A1087 | 0.33 |

The first three letters indicate the organism origin of the miRNA (miR); hsa, Homo sapiens. The numbering of miRNA genes is the sequential order that they were entered in the database.

A LNA miRNA microarray was used to detect differential expression in the experimental and control samples.

Fold change (FC) is the ratio of expression in the treated sample as compared to the untreated control. A fold change >1 means higher expression in the arsenite treated sample; whereas a fold change <1 means lower expression in the arsenite treated sample, as compared with the untreated control cells.

Quantitative PCR Analysis

Five miRNAs were selected for further analysis via qPCR to corroborate their expression levels obtained by microarray-based assay. Four of them were selected, based on their notorious differential expression and their relevance in carcinogenesis, and these were miR-21, miR-34b, miR-141 and miR-200a. The other miRNA, miR-PLUS-A1087, was selected for validation because it was the miRNA with greatest expression change (Table 1). The results acquired by both qPCR and microarray assays for those miRNAs are presented in (Table 2). Three of them, miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141, were found be up-regulated based on both the microarray and qPCR analyses techniques, and their p value of the qPCR fold change for all of them was consistently statistically significant (p<0.05), as compared with untreated controls (Table 2). The miRPLUS-A1087 was downregulated in the array and in qPCR but the qPCR fold change was marginally significant for this miRNA (Table 2). MiR-34b was down-regulated based on the array and up-regulated based on qPCR, although the fold change was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

MiRNAs expression validation by qPCR.

| miRNA | qPCR Untreated Cells (2^−(ΔCt)) |

qPCR Arsenite Treated Cells (2^−(ΔCt)) |

qPCR Fold Change |

Microarray Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | 70.44 ± 9.17† | 157 ± 28.54 | 2.22** | 2.22 |

| miR-34b | 0.44 ± 0.22 | 0.722 ± 0.54 | 1.64 | 0.56 |

| miR-Plus-A1087 | 8.6 ± 4.74 | 1.99 ± 1.06 | 0.231 | 0.33 |

| miR-200a | 4.35 ± 1.744 | 9.11 ± 1.159 | 2.09* | 1.81 |

| miR-141 | 10.08 ± 4.08 | 24.15 ± 3.93 | 2.39* | 1.92 |

ΔCt = delta (Δ) cycle threshold.

Average values and their corresponding standard deviation from triplicates.

Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test in the qPCR analysis;

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

Potential Signaling Pathways of Selected Target Genes

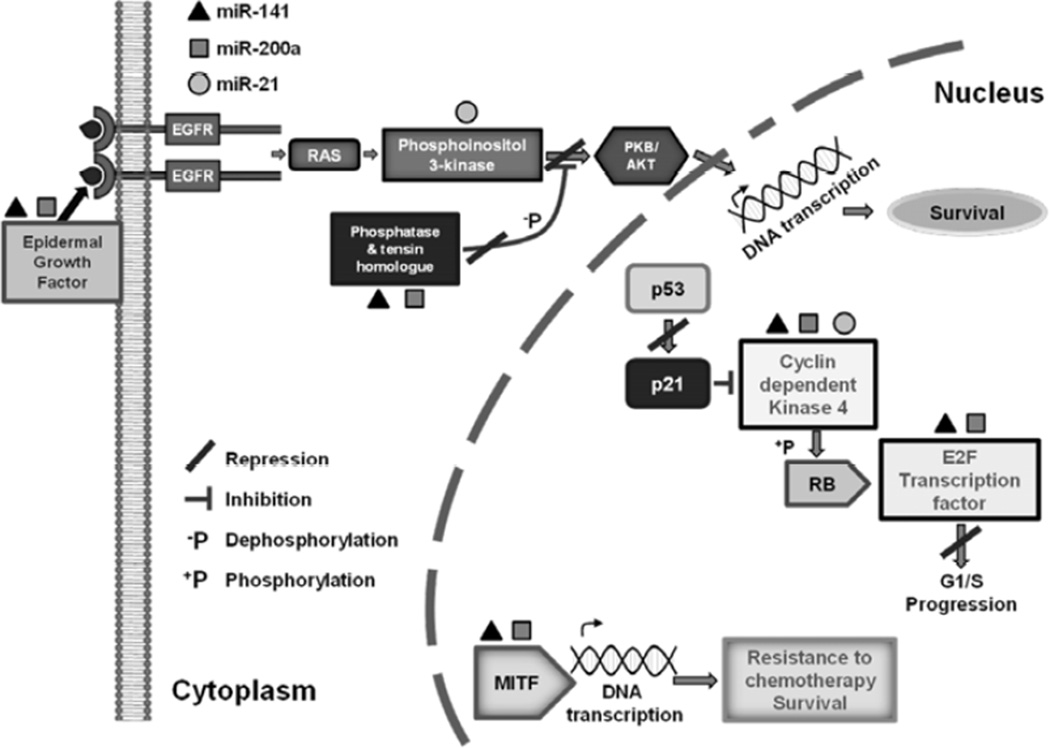

To establish the importance of miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 expression on arsenite-treated HaCaT cells and to investigate their involvement in the cellular metabolism context, the DIANA-mirPath computational database was utilized for in silico analysis. This database is designed to identify molecular pathways that are affected by single or multiple miRNAs occurrences. The DIANA-mirPath analysis revealed that at least one or more of the three selected miRNAs targeted genes involved in 16 pathways relevant to carcinogenesis (Table 3). The KEGG mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway was the most pronounced, comprising potential alteration of 27 target genes within its metabolic pathway (map04010). Additionally, the KEGG melanoma pathway (map05218), which is the most relevant pathway implicated in the skin carcinogenesis, was found to be affected by those three miRNAs and some of their potential targets genes are depicted in (Fig. 1). Other pathways appeared to be also potentially altered, including the Jak-STAT and several cancer related pathways (prostate, pancreatic and lung).

Table 3.

Cancer-related pathways affected by miR-21, miR-200a and/or miR-141.

| KEGG Pathway | Pathway ID | Number of miRNA Target Genes Within Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| MAPK signaling | hsa04010 | 27 |

| Wnt signaling | hsa04310 | 18 |

| Prostate cancer | hsa05215 | 12 |

| Jak-STAT | hsa04630 | 17 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | hsa04810 | 17 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | hsa05220 | 10 |

| Small cell lung cancer | hsa05222 | 10 |

| Pancreatic cancer | hsa05212 | 9 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | hsa04810 | 17 |

| Colorectal cancer | hsa05210 | 9 |

| TGF-beta signaling | hsa04350 | 9 |

| Cell cycle | hsa04110 | 10 |

| Melanoma | hsa05218 | 7 |

| Glioma | hsa05214 | 6 |

| Apoptosis | hsa04210 | 7 |

| p53 signaling | hsa04115 | 6 |

The three miRNAs whose fold change was statistically significant in the qPCR analysis (miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141) were used in the DIANA-mirPath database to identify potential signaling pathways regulated by them. The ones related to carcinogenesis are shown in the list. The number of genes targeted by one or more of the significant miRNAs (miR-21, 200a or miR-141) is annotated in the right column; Number of miRNA target genes within the respective pathway.

Fig. (1). KEGG Melanoma Pathway.

MiRPath showing the genes involved in the melanoma pathway that are potentially regulated by miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141. EGFR - Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; RAS - Rat Sarcoma proteins; PKB/AKT - Protein kinase B/AKT oncogene; RB - Retinoblastoma gene; p53-cellular tumor protein; p21- cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor; and MITF - Microphtalmia Transcription Factor.

The DIANA-miRPath data base was also used to find an intersection of potential target genes of miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141. We found common potential targets affected by all three miRNAs simultaneously (Fig. 1 and Table 4). Genes involved in the TGF-beta signaling pathway followed by actin regulation and cytokine pathways were the most commonly regulated by the three selected miRNAs. In addition, a group of target genes was also identified, participating in more than one biochemical pathway, including cyclin-dependent kinase 6, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II, activin receptor type 2A and phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate/5-kinase genes (Fig. 1 and Table 4).

Table 4.

Targeted genes regulated simultaneously by miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 that were up-regulated after exposure of HaCaT cells to arsenic.

| Targeted Genes Regulated by miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 |

KEGG Pathway | KEGG Pathway ID |

|---|---|---|

| Activin receptor type-2A | ||

| Bone morphogenetic receptor | TGF-beta signaling pathway | hsa04350 |

| Homodomain transcription factor 2 | ||

| T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis inducing protein 1, | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | hsa04810 |

| Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate/5-kinase | ||

| Jagged 1 protein | Notch signaling pathway | hsa04330 |

| Activin receptor type-2A | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | hsa04060 |

| Bone morphogenetic receptor | ||

| Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate/5-kinase | Inositol phosphate metabolism | hsa00562 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Non-small cell lung cancer | hsa05223 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Glioma | hsa05214 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | p53 signaling pathway | hsa04115 |

| Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate/5-kinase | Phosphatidylinositol signaling system (PI3K) | hsa04070 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Melanoma | hsa05218 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Pancreatic cancer | hsa05212 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | hsa05220 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Small cell lung cancer | hsa05222 |

| cAMP-responsive element-binding protein 5 | Prostate cancer | hsa05215 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Cell cycle | hsa04110 |

| Thyroid hormone receptor beta | Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction | hsa04080 |

The genes listed in the left column are common potential targets of miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141. In the center column are annotated some pathways in which those genes are involved.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate differential expression of miRNAs in human HaCaT keratinocytes after low-dose arsenic exposure. Previous reports revealed that long-term (20 or 28 weeks) low-dose exposure to sodium arsenite (0.1 or 0.5 or 1 µM) transformed non-malignant human cells, HaCaT keratinocytes, into a cancer cell phenotype or tumorigenic cells [30–32]. Thus, it was decided to expose the HaCaT cells to 500 nM of arsenite and study their miRNAs expression; an average arsenite concentration previously reported [30–32]. Five out of the thirty miRNAs identified to be altered by microarray analysis were selected for further validation via qPCR; on the basis of significant fold change expression (Table 2). Three out of those five, miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141, were found to be up-regulated by both microarray and qPCR assays (Table 2).

In this report, the simultaneous up-regulation of miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 provided an interesting point of intersection to understand convergent mechanisms of arsenic toxicology and to predict with more accuracy potential carcinogenetic targets of this metalloid. Moreover, our findings could be applied to additional metals- and metalloid-related toxicological disorders. Through the modulation of these three miRNAs, arsenic may affect several signaling pathways related to cell growth and proliferation as well as apoptosis regulation (Table 3). Some of the signaling pathways that are potentially regulated by miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 include pathways with a well-known role in carcinogenesis such as the MAPK, Jak-STAT and Wnt pathways (Table 3). These pathways have also been reported in the literature to be disturbed by arsenic exposure and contain many genes in common [42–44]. For these reasons, the genes that are simultaneously targeted by these three miRNAs throughout these pathways (Table 4) constitute an interesting cluster of genetic biomarkers that deserve special attention for future research and therapy design in skin carcinogenesis. In addition, these findings highlight the complexity of miRNA-mediated regulatory networks.

MiR-21 expression is involved in several pathologies from cancer to cardiovascular disease [45]. MiR-21 is over-expressed in most human tumors [46], including early pancreatic cancer lesions, pancreatic tumors, and pancreatic cancer-derived cell lines [47], breast [48], cervix [49], lung [50], and other types of cancer (for review, see Jazbutyte et al. 2010 [45]). This miRNA is one of the most frequently disturbed miRNA during carcinogenesis and its induction has been related to reduction of apoptosis [51] and is the most dramatically overexpressed miRNA in both solid and hematological malignancies [50]. Moreover, miR-21 up-regulation is commonly associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients and has been suggested to be a potential useful biomarker for cancer prognosis, as well as a potential therapeutic target in various diseases [25, 45, 47]. A recent report indicated that miR-21 inhibits the tumor suppressive activity of FBXO11 to promote tumorigenesis in melanoma, glioblastoma and prostate cancer [52]. For instance, it was found that by using an antisense suppressor of miR-21, this treatment significantly sensitized the K562 leukemic cells to arsenic trioxide by promoting apoptosis [53]. Thus, the regulation of miRNAs expression in combination with well-known anti-cancer drugs remains as a promising strategy for miRNA-based anticancer therapy.

Previous report proved that miR-141 and its targets PH domain leucine-rich-repeats protein phosphatase 1 and 2 (PHLPP1 and PHLPP2) play key roles in non-small cell lung cancer tumorigenesis [54]. MiR-141 was found to be significantly down-regulated in pancreatic cancer tissues and cell lines and also was found that miR-141 targets MAP4K4, which acts as a tumor suppressor in pancreatic cancer cells, providing a novel therapeutic option for miRNA-based pancreatic cancer therapy [55]. It was proposed that miR-141 expression is involved with the progression of bladder carcinoma and its overexpression is independently associated with favorable prognosis of patients affected with bladder cancer [25]. Also, MiR-141 conferred resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis by targeting YAP1 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [56]. In contrast, miR-141 functions as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) through the inhibition of HNF-3β expression, and suppressed proliferation and invasion by promoting the apoptosis of HCC cells [57]. Also, miR-141 inhibited tumor growth and metastasis by directly targeting transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) in gastric cancer [58].

It was suggested that the miR-200 family determines the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer progression phenotype [59]. Furthermore, both in epithelial cancer cells and other well-differentiated cancers, miR-200 family members are highly expressed strongly controlling the expression of the E-cadherin repressors, zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factors 1 and 2 (ZEB1 and ZEB2) [59]. The miR-200 family is a biomarker for cells that express E-cadherin but lack expression of vimentin, determining the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells [59]. Additionally, ZEB2 is over-expressed in various advanced stages of ovarian, gastric, and pancreatic cancer [60–62]. The possible role for miR-200a in lung adenocarcinoma was investigated, finding that low levels of miR-200a were significantly associated with poorer overall survival rate [63]. Furthermore, the miRNA-200 family regulates cellular motility and controls “stemness” in several cancers [64, 65]. Conversely, breast cancer with low expression of a miR-200a was correlated with improvement of clinical prognosis [63]. MiR-200 delivered into ovarian, lung, renal and basal-like breast cancers resulted in blocking cancer angiogenesis and suppressing metastasis [63]. Thus, miRNA-200 could be utilized also as potential therapeutic agents.

It is well documented that arsenite, or other arsenic-derived compounds, induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in several cell lines, included keratinocytes. A previous report proposed that arsenite exerts its cytotoxic effect on myoblasts by inducing apoptosis, evidenced by reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and Akt inactivation signaling pathway [66]. Also, arsenite was found to induce apoptosis in lymphoblastic cells [67]. Additionally, results indicated that arsenic-induced ROS apoptosis via several downstream alterations including genotoxicity, signal transduction, cell proliferation and inhibition of DNA repair [1]. Moreover, as consequence of long-term arsenite exposure, mouse lymphoid A20 cells manifested premature senescence through enhance DNA damage and p130 accumulation [68]. In cultured lung epithelial cells exposed to low levels of arsenic triggered oxidative stress and also activated the expression of genes related to stress [69]. In keratinocytes, NF-kB activity was increased by low concentrations of arsenic promoting proliferation, in contrast, the activity of NF-kB was not increased with high arsenic concentrations and Fas/FasL-associated apoptosis was induced; suggesting that the change of NF-kB activity is associated with arsenic-induced keratinocyte proliferation and cell death via the apoptosis pathway [70]. These results were confirmed for an additional study, concluding that arsenite, as well as arsenic pentoxide and arsenic iodide, was capable of inducing programmed cell death via DNA fragmentation in cultured HaCaT keratinocytes [71]. Moreover, it was proposed that arsenic-induced ROS formation provide evidence of apoptotic DNA fragmentation in keratinocytes, which may be implicated in the mechanism for arsenic-induced skin carcinogenicity [72]. Thus, arsenite-induced cytotoxicity involves oxidative stress, increases ROS production and DNA fragmentation, which cause apoptosis.

Arsenite-induced malignant transformation of human embryo lung fibroblast (HELF) cells was mediated by miR-21 overexpression, which was facilitated by ROS activation of the ERK/NF-κB pathway [73]. Additionally, it was proposed that miR-21 levels were over-expressed by the activations of ERK/NF-kB and JNK/c-Jun, and concomitantly, miR-21 inhibited target proteins of Pdcd4 and Spry1, which function as two feedback regulation loops of miR-21-Spry1-ERK/NF-kB and miR-21-Pdcd4-JNK/c-Jun in arsenite-induced transformation of HELF cells [74]. Also, it was reported that arsenic-exposed human umbilical vein endothelial (HUVEC) cells expressed alteration in miRNAs expression profiles, including miR-21 [75]; however, no change in miR-141 and miR-220a was reported. Moreover, miR-21 was found to be involved in both carcinogenesis and angiogenesis after arsenite exposure of non-tumorigenic SV40-transformed HBE and HUVEC cells [76]. In human primary neonatal keratinocytes (NHEKs) it was found that arsenic causes cumulative disruptions to epigenetic regulation of miR-34a expression and alteration of its target histone deacetylase SIRT1 protein, by disrupting the profile of histone acetylation and DNA methylation and by suppressing SIRT1 activity [77]. In a separate report, it was demonstrated that acute exposure of HaCaT keratinocytes to arsenite, p21waf1/Cip1 was up-regulated and Notch1 was down-regulated, favoring the Notch1 contribution on arsenic-induced keratinocyte transformation and cancerogenesis [78]. In addition, it was reported that arsenite induced epigenetic silencing of let-7c via Ras/NF-κB that is involved in the acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties and neoplastic transformation of HaCaT cells, which contribute to the tumorigenesis [79].

Investigating the expression profile of three cancer-associated miRNAs, miR-21, -141, and -221, in the blood of patients afflicted with metastatic prostate advanced cancer was found that they were significantly over-expressed as compared with non-metastatic cancer patients, where the alteration of the miR-141 was the most noticeable [80]. Also results suggested that both miR-141 and miR-200a are possible players in regulation of Th17/Treg differentiation and pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis [81]. Moreover, the up-regulation of miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 in our profiling implicates them as important carcinogenic biomarkers associated with arsenite exposure. Among the potential targets regulated by miR-21, miR-200a and miR-14, there are components of the Wnt and the PI3K pathways (Table 3, Table 4). There is a lack of knowledge about the signaling pathways that regulate epigenetic events and how cells communicate these signals among them. However, the Wnt pathway has been proposed as an ideal candidate for regulation of epigenetics due to its role in several stages of cellular differentiation [82]. The PI3K signaling pathway is involved in the movement of exosomes between cells [83], as well as many processes [84]. The transport of miRNAs and other regulatory molecules through exosomes is a proposed mechanism for epigenetic communication between cells, which could have great relevance to cellular differentiation and carcinogenesis [85]. Our results suggest that these pathways are tentative toxicological targets of arsenic through the differential expression of miRNAs. Due to the potential implications of these effects in epigenetic signaling, they deserve more in depth analyses in the future. Hence, miRNAs as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression are implicated in carcinogenesis, cancer diagnosis and prognosis, as well as potential targets for miRNA-based cancer therapy, alone or in combination with anticancer drugs.

The DIANA-mirPath analysis revealed that miR-21, miR-141 and miR-200a were not associated with squamous cell carcinoma, neither basal cell carcinoma; which both are non-melanoma types of skin cancer. Nevertheless, finding that the miR-21, miR-141 and miR-200a expression levels were altered in arsenite-exposed keratinocytes and that those miRNAs were also implicated with melanoma pathway is certainly interesting; being that melanoma is the most frequent, highly aggressive and deadly skin cancer type. Furthermore, the same miRNAs alteration pattern observed in arsenite-exposed HaCaT cells should be investigated by using a melanocyte cell line or a melanocyte derived cell line.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our study reveals that several miRNAs were altered in non-malignant human keratinocytes after low-concentration arsenic exposure. Also, the potential biochemical pathways that could be affected by arsenic were investigated and three of the most altered miRNAs, miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141, were found to regulate a highly complex pattern of genes and are associated to the melanoma pathway. Furthermore, these findings could be extended to characterize the role of potential miRNAs targets in the molecular toxicology networks provoked by arsenic and their inference in carcinogenesis. Additionally, increasing our understanding of up- or down-regulation of miRNAs and theirs involvement in cancer, as well as their roles in multifaceted regulatory pathways, may provide foundations for developing better therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the University Research Institute Grant (URI) of the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) to HG and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences-Support of Competitive Excellence Research Grant 1SC3GM103713 to RJA. Authors thank the staff of the Cytometry, Screening and Imaging Core Facility at UTEP for services and facilities provided. This core facility is supported by grant 2G12MD007592 to the Border Biomedical Research Center (BBRC) from Research Centers in Minority Institutions (RCMI) program and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of UTEP, NIMHD or NIH. Special thanks to Drs. Elisa Robles-Escajeda, Joanne T. Ellzey, Siddhartha Das and Kyle L. Johnson for their valuable critical comments; to Ms. Gladys Almodovar for her assistance with cell culture techniques and to Dr. Jeremy A. Ross for his support with the qPCR analysis; all employees of UTEP.

Biographies

H. Gonzalez

A. Varela-Ramirez

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes MF, Beck BD, Chen Y, Lewis AS, Thomas DJ. Arsenic exposure and toxicology: a historical perspective. Toxicol Sci. 2011;123(2):305–332. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandal BK, Suzuki KT. Arsenic round the world: a review. Talanta. 2002;58(1):201–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smedley PL, Kinniburgh DG. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl Geochem. 2002;17(5):517–568. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya P, Naidu R, Polya DA, Mukherjee A, Bundschuh J, Charlet L. Arsenic in hydrological processes-Sources, speciation, bioavailability and management. J Hydrol. 2014;518(Part C):279–283. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt KM, Srivastava RK, Elmets CA, Athar M. The mechanistic basis of arsenicosis: pathogenesis of skin cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;354(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Council NR, editor. NRC. Arsenic in drinking water. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. 2001 Update. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordstrom DK. Public health. Worldwide occurrences of arsenic in ground water. Science. 2002;296(5576):2143–2145. doi: 10.1126/science.1072375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson AR, Konat E, Alani RM. Melanoma biomarkers: current status and vision for the future. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6(2):105–117. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji Z, Flaherty KT, Tsao H. Targeting the RAS pathway in melanoma. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentry PR, Clewell HJ, Greene TB, Franzen AC, Yager JW. The impact of recent advances in research on arsenic cancer risk assessment. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69(1):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AH, Lingas EO, Rahman M. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: a public health emergency. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1093–1103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, et al. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2005;37(7):766–770. doi: 10.1038/ng1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garzon R, Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in Cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:167–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.053006.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeffries CD, Fried HM, Perkins DO. Additional layers of gene regulatory complexity from recently discovered microRNA mechanisms. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;42(8):1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brummer A, Hausser J. MicroRNA binding sites in the coding region of mRNAs: extending the repertoire of post-transcriptional gene regulation. Bioessays. 2014;36(6):617–626. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D152–D157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, et al. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403(6772):901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lema C, Cunningham MJ. MicroRNAs and their implications in toxicological research. Toxicol Lett. 2010;198(2):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor EL, Gant TW. Emerging fundamental roles for non-coding RNA species in toxicology. Toxicology. 2008;246(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price C, Chen J. MicroRNAs in Cancer Biology and Therapy: Current Status and Perspectives. Genes Dis. 2014;1(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medina PP, Nolde M, Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;467(7311):86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'Donnell KA, et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137(6):1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XL, Xie HY, Zhu CD, et al. Increased miR-141 expression is associated with diagnosis and favorable prognosis of patients with bladder cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;36(2):877–883. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J, Liu R, Luo C, et al. MiR-20a inhibits cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma metastasis and proliferation by directly targeting LIMK1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15(10):1340–1349. doi: 10.4161/cbt.29821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez VD, Becker-Santos DD, Vucic EA, Lam S, Lam WL. Induction of human squamous cell-type carcinomas by arsenic. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:454157. doi: 10.1155/2011/454157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106(3):761–771. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klimecki WT, Borchers AH, Egbert RE, Nagle RB, Carter DE, Bowden GT. Effects of acute and chronic arsenic exposure of human-derived keratinocytes in an In Vitro human skin equivalent system: a novel model of human arsenicism. Toxicol In Vitro. 1997;11(1–2):89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(97)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chien CW, Chiang MC, Ho IC, Lee TC. Association of chromosomal alterations with arsenite-induced tumorigenicity of human HaCaT keratinocytes in nude mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(17):1704–1710. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pi J, Diwan BA, Sun Y, et al. Arsenic-induced malignant transformation of human keratinocytes: involvement of Nrf2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(5):651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Y, Pi J, Wang X, Tokar EJ, Liu J, Waalkes MP. Aberrant cytokeratin expression during arsenic-induced acquired malignant phenotype in human HaCaT keratinocytes consistent with epidermal carcinogenesis. Toxicology. 2009;262(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunes LM, Robles-Escajeda E, Santiago-Vazquez Y, et al. The gender of cell lines matters when screening for novel anti-cancer drugs. AAPS J. 2014;16(4):872–874. doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9617-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lema C, Varela-Ramírez A, Aguilera RJ. Differential nuclear staining assay for high-throughput screening of cytotoxic compounds. Curr Cellular Biochem. 2011;1(1):1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peltier HJ, Latham GJ. Normalization of microRNA expression levels in quantitative RT-PCR assays: identification of suitable reference RNA targets in normal and cancerous human solid tissues. RNA. 2008;14(5):844–852. doi: 10.1261/rna.939908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papadopoulos GL, Alexiou P, Maragkakis M, Reczko M, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-mirPath: Integrating human and mouse microRNAs in pathways. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1991–1993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fendler A, Stephan C, Yousef GM, Jung K. MicroRNAs as regulators of signal transduction in urological tumors. Clin Chem. 2011;57(7):954–968. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.157727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melo SA, Esteller M. Dysregulation of microRNAs in cancer: playing with fire. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(13):2087–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munoz P, Iliou MS, Esteller M. Epigenetic alterations involved in cancer stem cell reprogramming. Mol Oncol. 2012;6(6):620–636. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chhabra R, Dubey R, Saini N. Cooperative and individualistic functions of the microRNAs in the miR-23a~27a~24-2 cluster and its implication in human diseases. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:232. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng HY, Li P, David M, Smithgall TE, Feng L, Lieberman MW. Arsenic inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23(20):3603–3612. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen TJ, Wozniak RJ, Eblin KE, Wnek SM, Gandolfi AJ, Futscher BW. Epigenetic mediated transcriptional activation of WNT5A participates in arsenical-associated malignant transformation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling M, Li Y, Xu Y, Pang Y, Shen L, Jiang R, et al. Regulation of miRNA-21 by reactive oxygen species-activated ERK/NF-kappaB in arsenite-induced cell transformation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(9):1508–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jazbutyte V, Thum T. MicroRNA-21: from cancer to cardiovascular disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11(8):926–935. doi: 10.2174/138945010791591403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nair VS, Maeda LS, Ioannidis JP. Clinical outcome prediction by microRNAs in human cancer: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(7):528–540. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.du Rieu MC, Torrisani J, Selves J, et al. MicroRNA-21 is induced early in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma precursor lesions. Clin Chem. 2010;56(4):603–612. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.137364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7065–7070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lui WO, Pourmand N, Patterson BK, Fire A. Patterns of known and novel small RNAs in human cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(13):6031–6043. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(1):39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang CH, Pfeffer SR, Sims M, et al. The oncogenic microRNA-21 inhibits the tumor suppressive activity of FBXO11 to promote tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(10):6037–6046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.632125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Zhu X, Gu J, et al. Anti-miR-21 oligonucleotide sensitizes leukemic K562 cells to arsenic trioxide by inducing apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(4):948–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mei Z, He Y, Feng J, et al. MicroRNA-141 promotes the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells by regulating expression of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(17):3055–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao G, Wang B, Liu Y, et al. miRNA-141, downregulated in pancreatic cancer, inhibits cell proliferation and invasion by directly targeting MAP4K4. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(11):2569–2580. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seki N. A commentary on MicroRNA-141 confers resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis by targeting YAP1 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Hum Genet. 2011;56(5):339–340. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin L, Liang H, Wang Y, et al. microRNA-141 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion and promotes apoptosis by targeting hepatocyte nuclear factor-3beta in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:879. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuo QF, Zhang R, Li BS, et al. MicroRNA-141 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in gastric cancer by directly targeting transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif, TAZ. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1623. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park SM, Gaur AB, Lengyel E, Peter ME. The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev. 2008;22(7):894–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.1640608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosivatz E, Becker I, Specht K, et al. Differential expression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulators snail, SIP1, and twist in gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(5):1881–1891. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elloul S, Silins I, Trope CG, Benshushan A, Davidson B, Reich R. Expression of E-cadherin transcriptional regulators in ovarian carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;449(5):520–528. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Imamichi Y, Konig A, Gress T, Menke A. Collagen type I-induced Smad-interacting protein 1 expression downregulates E-cadherin in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(16):2381–2385. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pecot CV, Rupaimoole R, Yang D, et al. Tumour angiogenesis regulation by the miR-200 family. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2427. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Korpal M, Kang Y. The emerging role of miR-200 family of microRNAs in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer metastasis. RNA Biol. 2008;5(3):115–119. doi: 10.4161/rna.5.3.6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia H, Cheung WK, Sze J, et al. miR-200a regulates epithelial-mesenchymal to stem-like transition via ZEB2 and beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(47):36995–37004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yen YP, Tsai KS, Chen YW, Huang CF, Yang RS, Liu SH. Arsenic induces apoptosis in myoblasts through a reactive oxygen species-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction pathway. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86(6):923–933. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0864-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zebboudj A, Maroui MA, Dutrieux J, et al. Sodium arsenite induces apoptosis and Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in lymphoblastoid cells. Biochimie. 2014;107(Pt B):247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okamura K, Nohara K. Long-term arsenite exposure induces premature senescence in B cell lymphoma A20 cells. Arch Toxicol. 2015;2015:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li M, Cai JF, Chiu JF. Arsenic induces oxidative stress and activates stress gene expressions in cultured lung epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem. 2002;87(1):29–38. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liao WT, Chang KL, Yu CL, Chen GS, Chang LW, Yu HS. Arsenic induces human keratinocyte apoptosis by the FAS/FAS ligand pathway, which correlates with alterations in nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1 activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(1):125–129. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tse WP, Cheng CH, Che CT, Lin ZX. Arsenic trioxide, arsenic pentoxide, and arsenic iodide inhibit human keratinocyte proliferation through the induction of apoptosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326(2):388–394. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.134080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shi H, Hudson LG, Ding W, et al. Arsenite causes DNA damage in keratinocytes via generation of hydroxyl radicals. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17(7):871–878. doi: 10.1021/tx049939e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ling M, Li Y, Xu Y, et al. Regulation of miRNA-21 by reactive oxygen species-activated ERK/NF-kappaB in arsenite-induced cell transformation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(9):1508–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shen L, Ling M, Li Y, et al. Feedback regulations of miR-21 and MAPKs via Pdcd4 and Spry1 are involved in arsenite-induced cell malignant transformation. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li X, Shi Y, Wei Y, Ma X, Li Y, Li R. Altered expression profiles of microRNAs upon arsenic exposure of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;34(2):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao Y, Xu Y, Luo F, et al. Angiogenesis, mediated by miR-21, is involved arsenite-induced carcinogenesis. Toxicol Lett. 2013;223(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herbert KJ, Holloway A, Cook AL, Chin SP, Snow ET. Arsenic exposure disrupts epigenetic regulation of SIRT1 in human keratinocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;281(1):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cialfi S, Palermo R, Manca S, et al. Loss of Notch1-dependent p21(Waf1/Cip1) expression influences the Notch1 outcome in tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(13):2046–2055. doi: 10.4161/cc.29079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang R, Li Y, Zhang A, et al. The acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties and neoplastic transformation of human keratinocytes induced by arsenite involves epigenetic silencing of let-7c via Ras/NF-kappaB. Toxicol Lett. 2014 Jun 5;227(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yaman Agaoglu F, Kovancilar M, Dizdar Y, et al. Investigation of miR-21, miR-141, and miR-221 in blood circulation of patients with prostate cancer. Tumour Biol. 2011;32(3):583–588. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Naghavian R, Ghaedi K, Kiani-Esfahani A, Ganjalikhani-Hakemi M, Etemadifar M, Nasr-Esfahani MH. miR-141 and miR-200a, Revelation of New Possible Players in Modulation of Th17/Treg Differentiation and Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0124555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mohammad HP, Baylin SB. Linking cell signaling and the epigenetic machinery. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pant S, Hilton H, Burczynski ME. The multifaceted exosome: Biogenesis, role in normal and aberrant cellular function, and frontiers for pharmacological and biomarker opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(11):1484–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fresno Vara JA, Casado E, de Castro J, Cejas P, Belda-Iniesta C, Gonzalez-Baron M. PI3K/Akt signalling pathway and cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(2):193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Record M, Subra C, Silvente-Poirot S, Poirot M. Exosomes as intercellular signalosomes and pharmacological effectors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81(10):1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]