Abstract

The trajectory, or slope, of cognitive decline may provide differentiation of older adults with and without incipient neurodegenerative disease. Cognitive aging phenotypes based on memory trajectories could be used as outcome measures for clinical trials or observational studies of risk and protective factors for dementia. This study used growth mixture modeling (GMM) to identify trajectory groups based on age- and education-corrected composite memory scores derived from immediate, delayed and recognition trials of the Selective Reminding Test. Participants included 2593 participants initially without dementia (mean age at entry = 76) in a community-based study of aging and dementia in northern Manhattan. Trajectory groups were compared on consensus diagnoses of dementia and structural MRI measures of hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortical thickness. Heterogeneity in memory trajectories allowed us to identify four groups: Stable-High (43.5 %), Stable-Low (17.1 %), Decliner (26.8 %), and Rapid Decliner (12.5 %). Decliners had more brain atrophy and higher rates of conversion to dementia. This study highlights the heterogeneity in cognitive aging and provides evidence that most elderly maintain memory function as they age. Associations with dementia and imaging measures validate subgroups of older adults identified with GMM based on their memory trajectories. Future research should use these memory trajectory phenotypes to determine whether dementia risk and protective factors differ for individuals following different memory trajectories.

Keywords: Cognitive aging, Alzheimer's disease, MRI

Introduction

Identifying the preclinical phase of late onset Alzheimer's disease (LOAD) has been a major focus of contemporary research. Over 25 % of older adults have brain pathology consistent with LOAD but appear to be clinically normal [1, 2]. A recent investigation of older adults who were clinically normal during life determined that the trajectory, or slope of decline, in cognitive performance differentiated those who had pathology consistent with LOAD at death from those who did not [2]. The authors of that report concluded that “subtle cognitive changes in the preclinical stage of LOAD may be more readily determined by changes over time compared to the person's baseline rather than differences compared to population norms”. Understanding variables associated with the decline or stability of cognitive function can help to identify factors that increase risk or protect against the development of LOAD and facilitate the development of interventions for high-risk individuals. In addition to providing an early marker of LOAD risk, change in cognitive functioning represents an important clinical outcome unto itself.

Previous research has shown that growth mixture modeling can be used to identify groups of older adults based on longitudinal cognitive trajectories [3, 4]. Further, resultant subgroups differ in terms of Alzheimer's neuropathology measured post-mortem [3]. However, previous studies have not investigated whether trajectory groups reflect underlying disease processes measured concurrently, as through serial neuroimaging. In addition, it is not known how well subgroups based on longitudinal cognitive trajectories correspond to clinical diagnoses of dementia.

We tested the hypothesis that at least two subgroups of older adults with stable or declining cognitive trajectories could be identified from longitudinal data. The specific goals of this study were to (1) identify groups of older adults based on individual differences in longitudinal memory trajectories; (2) validate resultant trajectory groups using dementia conversion rates and MRI measures of brain atrophy. Investigators have identified structural brain changes, measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as important biomarkers in the study of cognitive aging and preclinical LOAD [5]. This approach to cognitive aging phenotypes based on memory trajectories could be used as an outcome measure for clinical trials or observation studies of risk and protective factors for dementia.

Methods

Participants and setting

Data were included from persons without dementia initially who participated in at least two visits of the Washington Heights Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP), a prospective, community-based study of aging and dementia among Medicare-eligible adults aged 65 years and older residing in Northern Manhattan. Recruitment occurred at two time points, one beginning in 1992 (N = 1150) and the other in 1999 (N = 1443). Briefly, for both cohorts, a stratified random sample of 50 % of individuals aged 65 and older residing in Northern Manhattan was obtained from the Health Care Finance Administration. The sampling strategies and recruitment outcomes of these two cohorts have been described in detail elsewhere [6]. Participants have subsequently been followed at approximately 18–24 month intervals with similar assessments. The current study examined participants with up to five assessments over an average of 6.0 years (SD = 3.1 years). Recruitment, informed consent and study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University.

Neuropsychological testing

Participants underwent an in-person evaluation at baseline and each follow-up visit, including full medical and neurological examination and neuropsychological testing in English or Spanish. Episodic memory was the primary cognitive domain examined in this study, based on previous research that demonstrated the sensitivity of episodic memory to LOAD risk and progression [7]. Episodic memory was quantified as composite scores of total immediate recall, delayed recall, and delayed recognition trials from the Selective Reminding Test [8]. Each of these three variables measured at each occasion was standardized using means and standard deviations from the entire WHICAP sample at baseline. Composite scores were computed by averaging the standardized scores at each occasion. Variables included in this memory composite were identified through a previously-published factor analysis of the WHICAP neuropsychological battery [9]. Scores were then rescaled to a T-score metric with mean 50 and standard deviation 10.

Diagnosis of dementia and Alzheimer's disease

Diagnosis of dementia was established by a review of all available clinical information (not including radiological data) and was based on standard criteria. Following each clinical evaluation, a consensus conference reviewed available data to assign a research diagnosis. First, a diagnosis of dementia [10] was made, and then the type was determined based on research criteria for probable or possible AD, [11] Lewy body dementia, [12] vascular dementia, [13] and other dementias.

Structural magnetic resonance imaging

Structural MRI scans were available for a subset of 701 participants from the cohort chosen because they had no evidence of dementia and could tolerate the brain MRI [14]. These participants were younger (74.4 versus 76.6 years) and had more education (10.7 versus 9.5 years) than the 1892 participants who did not undergo MRI, but they did not differ in proportion of women, African Americans, or Hispanics. The MRI occurred 5.8 years after the baseline cognitive assessment (SD = 3.0 years). Images were obtained on a 1.5T Philips Intera scanner as previously described [14, 15]. T1-weighted (repetition time = 20 ms, echo time = 2.1 ms, field of view 240 cm, 256 × 160 matrix, 1.3 mm slice thickness) and T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR; repetition time = 11,000 ms, echo time = 144.0 ms, inversion time = 2800, field of view 25 cm, 2 nex, 256 × 192 matrix with 3 mm slice thickness) images were acquired in the axial orientation. Total intracranial volume, total hippocampal volume across hemispheres, and mean entorhinal cortical thickness across hemispheres were quantified with FreeSurfer version 5.1 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) using T1-weighted images. Follow-up MRI scans were available for 297 participants (mean interval between occasions = 4.6 years; SD = 0.8). These participants were more likely to have been followed longer than the sample-average of 6 years, were younger (73.7 versus 74.9 years), and had more education (11.1 versus 10.4 years) than the 402 participants who did not have a follow-up MRI, but they did not differ in proportion of women, African Americans, or Hispanics. The FreeSurfer longitudinal pipeline was used for participants with follow-up scans.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and group comparisons were conducted in SPSS 22. Growth mixture modeling (GMM) was conducted in Mplus 7. We identified groups of older adults based on longitudinal memory trajectories using GMM of episodic memory scores obtained at baseline and up to 4 follow-up visits. Sample sizes were: 2593, 2593, 2040, 1464, and 938 for the five occasions. Of the 1655 participants who did not finish the study, 34.7 % were confirmed to have died prior to their next scheduled visit. Missing data were managed with full information maximum likelihood.

In order to identify differences and changes in episodic memory trajectories above and beyond those expected based on education and age, we first corrected all the memory scores using a regression model. Specifically, a regression of baseline memory score on baseline age, education, age × education and a cubic polynomial of education (included to capture non-linear education-memory relationship) was performed, and the resulting equation was used to adjust the baseline and all follow-up measurements. The equation was: age/education-corrected memory score = original memory score – (70.6979 – 0.2510 × age – 0.0068 × age × education + 1.0824 × education + 0.0169 × education2 – 0.0020 × education3), where age is age at the particular visit, and education is years of education centered at grade 9. As a result, an age/education-corrected memory score of zero indicates the person has memory equal to what would be expected for their age and education, while values greater (or less) than 0 indicate higher (or lower) than expected. The units of the corrected scores are the same as the original memory score; hence slopes (i.e., rates of decline) are expressed in T-score metric. To identify trajectory groups, we fit GMMs to the age/education- corrected memory scores with linear time trends that accommodated individual differences in time between visits. Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) of GMMs with different numbers of latent classes was examined to determine the optimal number of trajectory classes.

To validate the resultant trajectory groups, rates of dementia conversion across groups were compared using Cox regression, controlling for age, sex, education and race/ethnicity. To validate the trajectory groups in the subset of 701 participants with an initial structural MRI, we compared total hippocampal volume and mean entorhinal cortical thickness across groups using analyses of variance (ANOVA), controlling for age, sex and total intracranial volume. In the subset of 297 participants with a second MRI, we compared rates of change in total hippocampal volume and mean entorhinal cortical thickness across groups using repeated-measures ANOVA, controlling for age, sex and total intracranial volume. Demographic differences between groups were characterized using unadjusted ANOVA for continuous variables and Chi square tests for categorical variables.

Results

Identifying memory trajectory groups

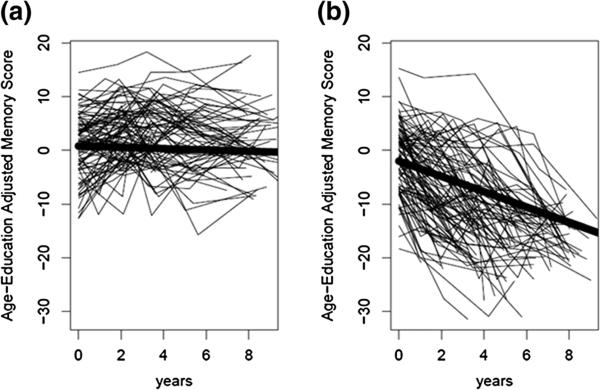

Models estimating one, two or three classes produced BIC values of 59,603.3, 59,390.0 and 59,395.1, respectively. Memory trajectories were most parsimoniously summarized (i.e., smallest BIC) by two classes: “Stable” (74.7 %) and “Decliner” (25.3 %). On average, participants in the “Stable” group scored above the sample-average by 0.79 T-score points at baseline and exhibited a decline of 0.12 T-score points per year. Participants in the “Decliner” group scored below the sample-average by –2.01 T-score points at baseline and exhibited a decline of 1.43 T-score points per year. There were substantial individual differences in trajectories within class, as shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, the intercepts varied significantly (“Stable”: p < 0.001; “Decliner”: p < 0.001) in both classes, and there were significant individual differences in slopes (i.e., rates of decline) within the “Decliner” class (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Representative individual memory trajectories within (a) stable and (b) declining classes identified through growth mixture modeling

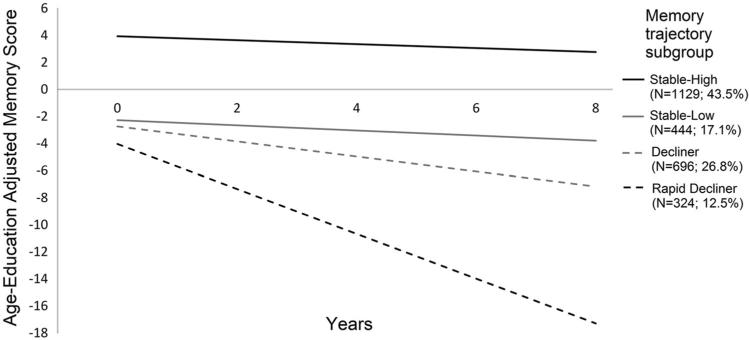

Given the substantial individual variability within the two-class model, we sought to establish more homogeneous groups for validation and characterization. Specifically, the two classes differed in both baseline cognitive level and rate of cognitive decline, disallowing comparisons between groups with similar baseline cognition but differing rates of change or between groups with similar rates of cognitive change but differing baseline cognition. Therefore, these classes were further refined into four groups based on the following criteria: (1) “Stable-High”: ≥80 % probability of being in the stable class and intercept ≥0 (43.5 %) indicating above average memory at baseline; (2) “Stable-Low”: ≥80 % probability in stable class and intercept <0 (17.1 %) indicating below average memory at baseline; (3) “Decliner”: <80 % probability in stable class and slope ≥–1 T-score point per year (26.8 %) and (4) “Rapid Decliner”: <80 % probability in stable class and slope <–1 T-score point per year (12.5 %). The cut-off of greater than or less than 1 T-score point per year to delineate the two decliner groups was chosen due to its simplicity for dissemination as a clinical recommendation. We chose to delineate between the stable and decliner groups conservatively requiring >80 % probability of being in the stable class (from the GMM posterior probability estimates) before identifying individuals as stable. Note that this scheme resulted in only 60.6 % (43.5 + 17.1 %) of individuals being labeled as stable in comparison to the 74.7 % identified as stable from the two-class GMM if the more common >50 % posterior probability rule is used. Figure 2 shows average trajectories for these four groups.

Fig. 2.

Average memory trajectories of the four groups

Table 1 shows characteristics of the four groups. Specifically, the two stable groups were significantly younger than both groups of decliners, and the “Rapid-Decline” group was 1 year older than the “Decline” group, on average. There was a lower proportion of women in the “Stable-Low” group, compared to the “Stable-High” group. The “Stable-High” group had attained more education than the two groups of decliners. The two stable groups comprised lower proportions of African Americans than both groups of decliners. There were more Hispanic older adults in the “Stable-Low” group, compared to the “Stable-High” and “Decline” groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the four trajectory groups

| Stable-high (N = 1129) | Stable-low (N = 444) | Decline (N = 696) | Rapid decline (N = 324) | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 74.9 ± 5.8 | 74.6 ± 5.1 | 77.4 ± 6.5 | 78.6 ± 6.4 | SH = SL < D < RD |

| N, % female | 834 (73.9) | 287 (64.6) | 443 (63.6) | 217 (67.0) | SH > SL = D = RD |

| Education | 10.4 ± 4.8 | 9.8 ± 5.9 | 9.4 ± 4.6 | 9.3 ± 4.8 | SL = SH > D = RD |

| N, % African American | 318 (28.2) | 135 (30.4) | 260 (37.4) | 124 (38.3) | SH = SL< D=RD |

| N, % Hispanic | 407 (36.0) | 212 (47.7) | 264 (38.1) | 133 (41.0) | SH < SL> D=RD |

| Number of study visits | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | SH = SL> D=RD |

| N, % with baseline MRI | 334 (29.6) | 168 (37.8) | 138 (19.8) | 61 (18.8) | SH < SL> D=RD |

| N, % with follow-up MRI | 153 (13.6) | 77 (17.3) | 47 (6.8) | 20 (6.2) | SH = SL> D=RD |

| Adjusted memory score at baseline (intercept) | 3.9 (2.6) | –2.3 (1.8) | –2.7 (3.6) | –4.0 (5.0) | SH > SL = D > RD |

| Annualized change in adjusted memory score (slope) | –0.1 (0.1) | –0.2 (0.1) | –0.6 (0.2) | –1.7 (0.5) | SH > SL > D > RD |

| Total hippocampal volume | |||||

| Time 1 (N = 701) | 6868.6 (818.5) | 6890.4 (823.5) | 6588.3 (1093.3) | 6061.3 (1045.8) | SH = SL > D > RD |

| Time 2 (N = 297) | 6393.9 (820.9) | 6309.7 (928.7) | 5951.7 (1174.7) | 5170.1 (1328.4) | SH = SL > RD < D |

| Mean entorhinal cortical thickness | |||||

| Time 1 (N = 701) | 3.1 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.4) | SH = SL > D > RD |

| Time 2 (N = 297) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | 2.7 (0.4) | SH = SL> D=RD |

| N, % incident dementia | 74 (6.6) | 80 (18.0) | 210 (30.2) | 231 (71.3) | SH < SL < D < RD |

Validating memory trajectory groups

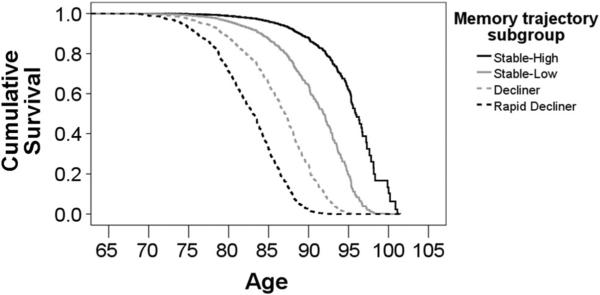

As expected, the frequency of conversion to dementia differed across the four groups (X2(3) = 626.61; p < 0.001, Table 1). Results of survival analysis adjusting for age, sex, education, and race/ethnicity confirmed different conversion rates, with Rapid Decliners showing the fastest rates, followed by Decliners, Stable-Low, and Stable-High (Fig. 3). Among cases of dementia, 93 % met criteria for LOAD [11]. Other cases met criteria for other dementias (e.g., Lewy body dementia).

Fig. 3.

Rates of dementia conversion by group, adjusting for baseline age, sex, education, and race/ethnicity

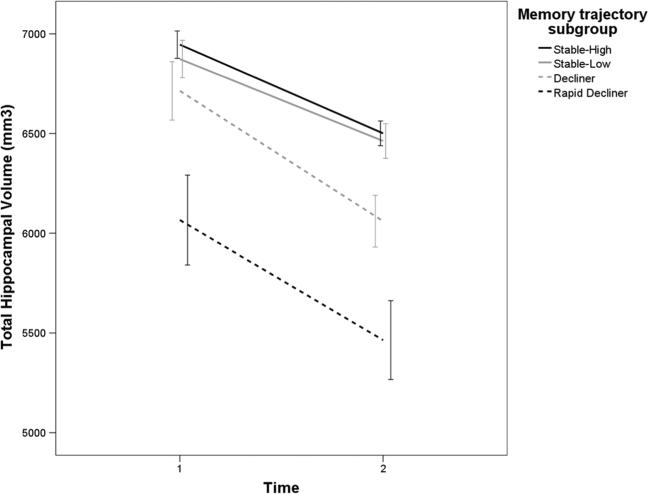

Adjusting for age, sex, and total intracranial volume, hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortical thickness at both time points differed across groups, with “Rapid Decliners” showing the lowest values (see Table 1). Adjusting for age, sex and total intracranial volume, the rate of hippocampal atrophy across the two MRI sessions was greatest among the two declining groups, compared with the two stable groups (F (3, 288) = 4.824, p = 0.003). Figure 4 shows rates of hippocampal atrophy by trajectory group. Similarly, the rate of entorhinal cortical thinning was greatest among the two declining groups, compared with the two stable groups, independent of age, sex and total intracranial volume (F (3, 288) = 4.087, p = 0.007).

Fig. 4.

Hippocampal atrophy varies as a function of trajectory group, independent of age, sex and total intracranial volume. Error bars reflect 95 % confidence intervals

Discussion

This study identified and validated four groups of initially cognitively healthy older adults based on memory trajectories over an average of 6 years. Two groups remained cognitively stable over time, and two groups showed declining memory scores over time. Evidence for the existence of four groups highlights the heterogeneity in cognitive aging. Our finding that a large segment of older adults (60.6 %) were best characterized as having stable memory performance indicates that most older adults are able to maintain cognitive stability with age, consistent with previous analyses [3, 4].

As expected, the four memory trajectory groups differed in rates of conversion to dementia and LOAD, specifically, confirming that memory trajectory is an excellent indicator of clinical disease. Among the subset of 701 participants who underwent structural MRI, the four memory trajectory groups showed different hippocampal volumes and entorhinal cortical thicknesses. Among the subset of 297 participants who underwent serial structural MRI, the four memory trajectory groups showed different rates of hippocampal and entorhinal cortical atrophy. Structural MRI findings, consistent with neurodegeneration, indicate that the memory decline occurred simultaneously.

Among individuals with stable memory trajectories, sex differentiated groups that differed primarily in baseline level of performance (i.e., “Stable-High” versus “Stable-Low”). Specifically, women obtained higher age- and education-corrected memory scores at baseline than men [16]. This baseline memory advantage did not translate into different subsequent patterns of decline, as sex did not differentiate between groups with stable versus declining trajectories. Several demographic variables were associated with memory decline versus stability among participants with similar baseline cognitive level (i.e., “Stable-Low” versus “Decliner”), including older age [17], less education [18], and race/ethnicity [19]. Among decliners, only older age was associated with more rapid memory decline (i.e., “Rapid Decliner” versus “Decliner”). These findings highlight the importance of incorporating rates of cognitive decline, not just cognitive level, in cognitive aging research. Variables associated with cognitive level may not predict subsequent rates of cognitive change, or vice versa.

Strengths of this empirically-guided approach to trajectory grouping include the large number of well-characterized, educationally diverse and multi-ethnic older adults, as previous work was conducted in samples that were smaller and more homogeneous with regard to age [3] and/or other demographics [3, 4], and life experiences [4]. Thus, this study allowed for a more comprehensive investigation of the relationships between demographics, including race/ethnicity, and memory trajectories. In addition, the availability of longitudinal MRI and consensus diagnoses of incident dementia in the current study provided validation of memory trajectory subgroups against markers of brain pathology and clinical disease measured concurrently. A novel finding of this study was that even the highest-performing group that, on average, exhibited a relatively stable memory trajectory contained individuals who converted to dementia. Future research should explore whether the predictors of incident dementia differ for this highly select subgroup.

This study demonstrates the heterogeneity of cognitive aging. Most elderly maintain cognitive function as they age, with a subset exhibiting differing rates of pathological decline. Growth mixture modeling can be used to guide subgrouping of older adults based on longitudinal memory trajectories, which are sensitive to both clinical disease and underlying neurodegeneration. The use of cognitive trajectory phenotypes to identify risk and protective factors for LOAD prior to the clinical diagnosis would be a worthwhile endeavor. Such work would allow clinicians to make more individualized prognoses based on a patient's unique cognitive history when evaluating dementia risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded with support from the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers AG047963, AG037212, AG034189, AG007232). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Etical standard All participants gave informed consent before entering the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University.

References

- 1.Crystal H, Dickson D, Fuld P, et al. Clinico-pathologic studies in dementia: nondemented subjects with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1988;38:1682–1687. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.11.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monsell SE, Mock C, Hassenstab J, et al. Neuropsycho-logical changes in asymptomatic persons with Alzheimer disease neuropathology. Neurology. 2014;83:434–440. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayden KM, Reed BR, Manly JJ, et al. Cognitive decline in the elderly: an analysis of population heterogeneity. Age Ageing. 2011;40:684–689. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muniz Terrera G, Brayne C, Matthews F, the CC75C Study Collaboration Group One size fits all? Why we need more sophisticated analytical methods in the explanation of trajectories of cognition in older age and their potential risk factors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:291–299. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack CR, Knopman D, Jagust W, et al. Update on hypothetical model of Alzheimer's disease biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, et al. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collie A, Maruff P. The neuropsychology of preclinical Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci Biobeh Rev. 2000;24:365–374. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology. 1974;24:1019–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.11.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siedlecki KL, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Schupf N, Tang M-X, Stern Y. Do neuropsychological tests have the same meaning in Spanish speakers as they do in English speakers? Neuropsychology. 2010;24:402–411. doi: 10.1037/a0017515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, revised. 3rd edn. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann G, Drachman D, FolsteinM Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKeith IG, Perry EK, Perry PH. Report of the second dementia with Lewy body international workshop: diagnosis and treatment. Neurology. 1999;53:902. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for research studies: report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brickman AM, Schupf N, Manly JJ, et al. Brain morphology in older African Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and whites from northern Manhattan. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brickman AM, Zahodne LB, Guzman VA, et al. Reconsidering harbingers of dementia: progression of parietal lobe white matter hyperintensities predicts Alzheimer's disease incidence. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleecker ML, Bolla-Wilson K, Agnew J, Meyers DA. Age-related differences in verbal memory. J Clin Psychol. 1988;44:403–411. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198805)44:3<403::aid-jclp2270440315>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhaeghen P, Salthouse TA. Meta-analyses of age-cognition relations in adulthood: estimates of linear and nonlinear age effects and structural models. Psychol Bull. 1997;122:231–249. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piccinin AM, Muniz G, Clouston S, et al. Coordinated analysis of age, sex, and education effects on change in MMSE scores. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68:374–390. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan AA, Marsiske M, Whitfield KE. Characterizing and explaining differences in cognitive test performance between African American and European American older adults. Exp Aging Res. 2008;34:80–100. doi: 10.1080/03610730701776427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]