Abstract

We have developed an enantioselective, copper(I)-catalyzed addition of terminal alkynes to isochroman ketals to set diaryl, tetrasubstituted stereocenters. The success of this reaction relies on identification of a Cu/PyBox catalyst capable of distinguishing the faces of the diaryl-substituted oxocarbenium ion. This challenging transformation enables efficient conversion of readily available, racemic ketals to high-value, enantioenriched isochroman products with fully substituted stereogenic centers. High yields and enantiomeric excesses are observed for various isochroman ketals and an array of alkynes.

Keywords: oxocarbenium ion, asymmetric catalysis, alkynes, oxygen heterocycles, enantioselectivity

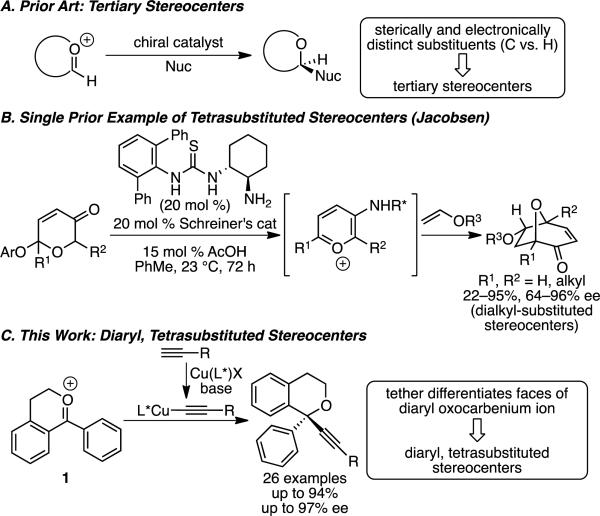

Oxygen heterocycles with α-tetrasubstituted stereocenters possess biological activities against various targets, including as anti-oxidant, anti-depressant, and anti-HIV agents.[1] A common strategy for asymmetric synthesis of these molecules is to first install the stereocenter, and then to perform a cyclization.[1e, 2] This approach often relies on enantioselective additions to ketone substrates, which generally require significant differences in the electronic or steric character of their substituents to achieve high ee's.[3],[1e, 4],[5] In particular, enantioselective additions to diaryl ketones are rare, and none enable addition of an acetylide to our knowledge.[6] We envisioned that enantioselective addition to a cyclic oxocarbenium ion might provide an opportunity for differentiating the faces of a diaryl-substituted oxocarbenium ion, providing an alternative strategy to set α-diaryl, tetrasubstituted stereocenters on oxygen heterocycles. By tethering one aryl group to the oxygen, the otherwise similar aryl substituents are differentiated by freedom of rotation and by their relationship to the oxygen substituents (alkyl vs. lone pair). These factors make the geometry of the oxocarbenium ion similar to that of a trisubstituted olefin, which has been utilized in powerful enantioselective transformations.[7] Notably, however, the oxocarbenium ion reacts as an electrophile in contrast to its alkene analogue.

However, enantioselective additions of carbon nucleophiles to oxocarbenium ions remain challenging, and no known method enables formation of the proposed motif. Significant advances in enantioselective additions to cyclic oxocarbenium ions have been made by using organo- and/or Lewis acid catalysts to deliver a number of different carbon nucleophiles.[8] We have developed a copper(I)-catalyzed method to enable enantioselective alkynylation via addition of a chiral organometallic nucleophile.[9] However, the vast majority of enantioselective additions of carbon nucleophiles are limited to the formation of tertiary stereocenters via additions to oxocarbenium ions with sterically and electronically distinct substituents on the cationic carbon (C vs. H, Scheme 1A).[10] Only a single method exists for the formation of tetrasubstituted stereocenters via enantioselective addition to oxocarbenium ions; Jacobsen's thiourea-catalyzed [5+2] cycloaddition of pyrilium ions enables formation of α-trialkyl tetrasubstituted stereocenters on 8-oxabicylcooctanes (Scheme 1B).[8k, 8l] Beyond this, there are no examples of setting tetrasubstituted stereocenters via additions of carbon nucleophiles to oxocarbenium ions, and no such additions enable formation of challenging diaryl tetrasubstituted stereocenters. We now report the first enantioselective addition to oxocarbenium ions to provide α-diaryl tetrasubstituted stereocenters. This alkynylation harnesses a Cu/PyBox catalyst to deliver chiral organometallic nucleophiles to diaryl-substituted oxocarbenium ions in high yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 1C).

Scheme 1.

Enantioselective Additions to Oxocarbenium Ions.

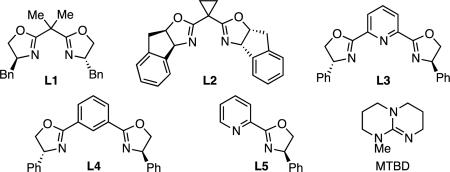

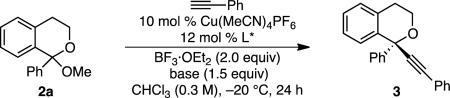

We began by studying the alkynylation of isochroman ketal 2a, which is readily synthesized by addition of phenyl lithium to isochromanone. Under conditions similar to those used in the formation of tertiary stereocenters, low yields and enantioselectiv ities of product 3 were observed (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).[9a] Higher yield was observed when CHCl3 was employed as solvent, but the product was nearly racemic (entry 3). However, when benzyl-substituted L1 was replaced with phenyl-substituted bis(oxazoline) L2 or phenyl-substituted pyridine-(bis)oxazoline (PyBox) L3, promising enantioselectivities were obtained (entries 4 and 5). Base also affected the enantioselectivity (entries 5–8). With the use of L3 and 7-methyl-1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (MTBD), 84% ee was obtained, albeit in 22% yield (entry 8). Optimization of the copper salt, equivalents of base, concentration and temperature led to an optimized 87% yield and 78% ee (entries 9 and 10). Other pyridine-bis(oxazoline) ligands did not provide higher enantioselectivities.[11]

Table 1.

Optimization of Alkynylation of Acetal 2a[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | L* | base | yield(%)[b] | ee (%)[c] |

| 1[d],[e] | L1 | iPr2NEt | 21 | 8 |

| 2[e] | L1 | iPr2NEt | 20 | 0 |

| 3 | L1 | iPr2NEt | 83 | 4 |

| 4 | L2 | iPr2NEt | 83 | 37 |

| 5 | L3 | iPr2NEt | 24 | 27 |

| 6 | L2 | DBU | 16 | 36 |

| 7 | L3 | DBU | 32 | 81 |

| 8 | L3 | MTBD | 22 | 84 |

| 9[f] | L3 | MTBD | 12 | 87 |

| 10[f],[g],[h] | L3 | MTBD | 87 | 78 |

Conditions: Acetal 2a (0.08 mmol, 1.0 equv), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (0.008 mmol, 10 mol %), L*(0.01 mmol, 12 mol %), phenylacetylene (0.096 mmol, 1.2 equiv), BF3·Et2O (0.16 mmol, 2.0 equv), base (0.12 mmol, 1.5 equv), CHCl3 (0.3M), −20 °C, 24 h, unless otherwise noted.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase.

TMSOTf (1.2 equiv) replaced BF3·-Et2O.

Et2O instead of CHCl3.

CuSPh instead of Cu(MeCN)4PF6.

MTBD (1.55 equiv), CHCl3 (0.15 M).

4 °C.

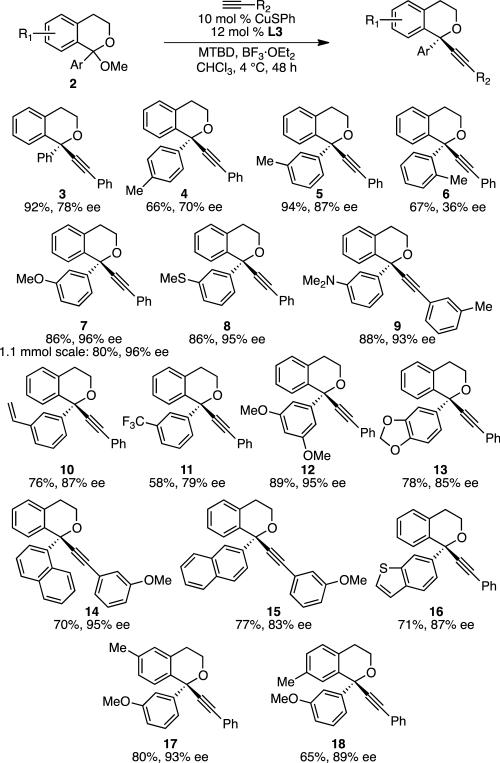

Under the optimized conditions (Table 1, entry 10), a variety of isochroman ketals successfully underwent alkynylation (Scheme 2). Product 3 was isolated in 92% yield and 78% ee, which we deemed to be impressive selectivity given the challenging nature of this highly substituted stereocenter. With this success, we explored other ketals. As discussed below, even higher enantioselectivities, up to 97% ee, were realized with substituted substrates. Investigation of substituent effects on the 1-aryl group (Ar) showed that useful yields are observed in the formation o-, m-, and p-tolyl-substituted products (4–6). However, low enantioselectivity is observed for o-tolyl-substituted 6, indicating the limit of steric hindrance. Higher enantioselectiv ities are obtained with meta substituents; m-heteroatom substituents led to the best enantioselectivities (up to 97% ee, 7–9, 12). A range of functional groups was well tolerated, including ethers (7, 12, 17, 18), thioethers (8), anilines (9), alkenes (10), trifluoromethyls (11), and acetals (13). Although the o-tolyl substituent led to low ee, 1-naphthyl-substituted 14 was formed in 95% ee. Substrates with 2-naphthyl and heteroaryl substituents also underwent alkynylation (15 and 16). Substitution on the benzopyranyl core was also well tolerated (17 and 18). Importantly, increasing the scale of the reaction results in similar yield with no change in enantioselectivity (see 7). The absolute configuration of 14 was determined by X-ray crystallography.[12] The configurations of other products were assigned by analogy. Unfortunately, 1-alkylisochroman acetals are poor substrates under these conditions; no desired product was observed in the reaction of 1-methoxy-1-methylisochromane with phenylacetylene.[13]

Scheme 2.

Scope of Isochroman Acetals. Conditions: acetal 2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), CuSPh (0.02 mmol, 10 mol %), (R,R)-L3 (0.024 mmol, 12 mol %), alkyne (0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv), BF3·Et2O (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), MTBD (0.31 mmol, 1.55 equiv), CHCl3 (0.15M), 4 °C, 48 h. Average isolated yield from duplicate experiments (±5%) and average ee from duplicate experiments as determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase (±2%), unless otherwise noted. For 8, 10, and 17, result of a single experiment.

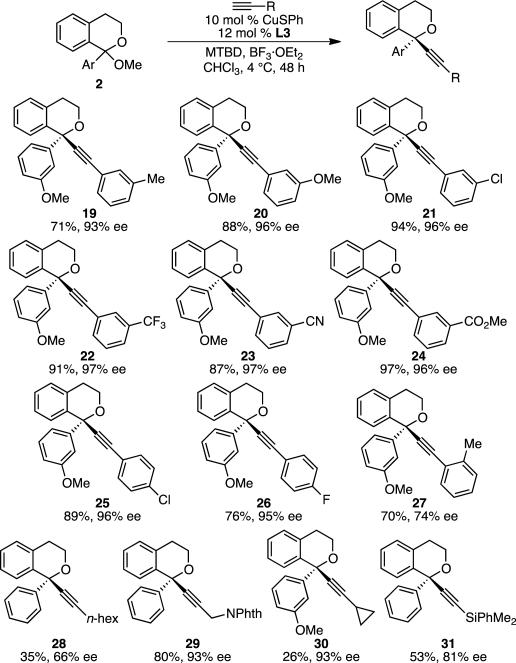

Good yields and high enantioselectivities were observed across a range of acetylenes (Scheme 3). In particular, electron-poor to moderately electron-rich aryl groups were well tolerated, including various m-substituents (19–24) and electron-poor p-substituents (25 and 26). Functional groups including ethers (20), trifluoromethyls (22), nitriles (23), esters (24), and halides (21, 25, 26) can be incorporated. O-Tolyl 27 was also formed in 75% yield, albeit 73% ee. However, the use of aryl acetylenes with electron-rich p-substituents, such as p-(dimethylamino) or p-methyl, led to low or irreproducible enantioselectivities (0 and 20–90% ee, respectively, not shown). We hypothesize that electron-rich isochroman products may undergo epimerization via Lewis acid-induced ionization of the benzylic C–O bond leading to a trityl-like cation. With respect to alkyl-substituted alkynes, 1-octyne gave low yield and modest enantioselectivity (28). However, addition of propargyl phthalimide resulted in 80% yield of product 29 in 93% ee. High enantioselectivity was also observed in the addition of cyclopropylacetylene (30). Silyl acetylenes also underwent addition. The addition of (trimethylsilyl)acetylene resulted in modest yield (40% by 1H NMR), but relatively high enantioselectivity (82% ee, not shown). (Dimethylphenylsilyl)acetylene showed greater reactivity, giving 53% yield and 80% ee of silyl-protected acetylene 31.

Scheme 3.

Scope of Alkynes. Conditions: Acetal 2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), CuSPh (0.02 mmol, 10 mol %), (R,R)-L3 (0.024 mmol, 12 mol %), alkyne (0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv), BF3·Et2O (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), MTBD (0.31 mmol, 1.55 equiv), CHCl3 (0.15M), 4 °C, 48 h. Average isolated yield from duplicate experiments (±5%) and average ee from duplicate experiments as determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase (±2%), unless otherwise noted. For 26, 28, and 30, result of a single experiment.

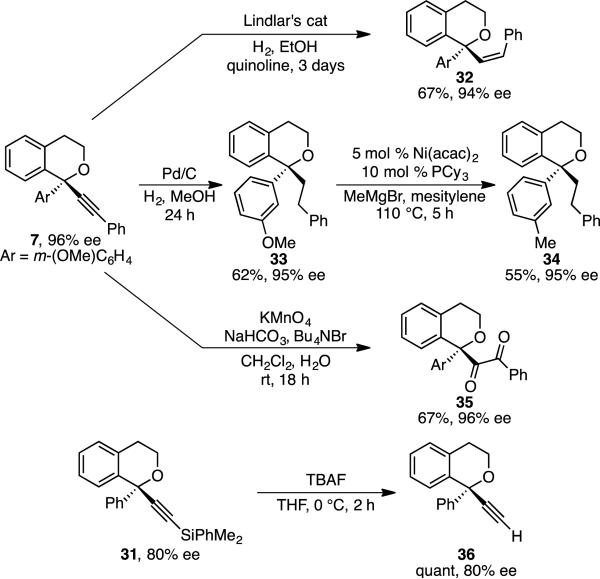

The products can be easily elaborated. Reduction of alkyne 7 gives vinyl- and alkyl-substituted isochromans 32 and 33 in good yields and high enantiopurities (Scheme 4). Oxidation to diketone 35 was accomplished in 67% yield and perfect stereochemical fidelity.[14] As noted above, m-methoxyphenyl-substituted isochroman products are formed in the highest enantioselectivities. This m-methoxy substituent is easily functionalized via cross coupling; it can be converted to a m-methyl group without loss in ee (34).[15] Finally, deprotection of silyl acetylene 31 was accomplished in quantitative yield and perfect stereochemical fidelity to deliver terminal alkyne 36.

Scheme 4.

Elaboration of products

For mechanism, this reaction likely proceeds via addition of a chiral copper acetylide to an oxocarbenium ion intermediate (Scheme 1C). Two equivalents of BF3·OEt2 are required; less leads to lower yields and ee's, likely due to incomplete ionization to the oxocarbenium ion. However, the isolated isochroman products racemize when subjected to BF3·OEt2.[11] As with other acetals,[16] BF4− was detected in the reaction of ketal 2a with BF3 (2 equiv) by 19F NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. This observation suggests that the second equivalent of BF3 reacts with F3B(OMe)−, which forms upon ionization of the ketal. This disproportionation results in the less Lewis acidic BF2(OMe), which seems incapable of epimerizing most products.

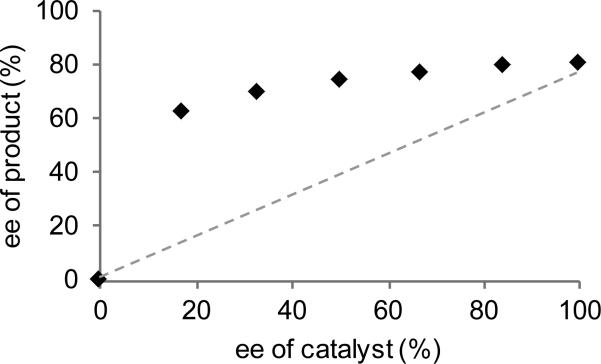

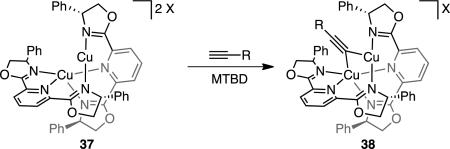

We are also interested in understanding the structure of the putative chiral copper acetylide. Although PyBox ligands often enforce a square planar geometry on a M–X fragment, there is no electronic benefit for copper(I) complexes to adopt this more sterically crowded geometry. We considered that PyBox L3 may act instead as a bidentate ligand, with either the pyridine or one oxazoline arm dissociating, but models for these types of coordination geometries resulted in much lower enantioselectivities (L4: 4% ee; L5: 28% ee).[17] Another possibility is a dimeric (or other higher order) copper/L3 catalyst. Cu2(L3)2X2 complexes (37, eq 2) have been previously observed,[18] and these dinuclear copper catalysts have been proposed to proceed via dicopper acetylide intermediates (38) in related reactions.[18c, 19] Consistent with the presence of higher order copper/L3 species, a positive nonlinear correlation is observed between the ee of L3 and ee of product (Fig. 1).[20] Although this data does not exclude the possibility that these higher order copper species may exist in an off-cycle reservoir, we currently favor a dicopper acetylide intermediate, given their importance in other copper acetylide chemistry. Due to the multiple possible catalyst structures, we cannot yet propose a detailed rationale for the observed stereochemistry. However, we hypothesize that the role of the phenyl substituents on (R)-Ph-PyBox(L3) is largely steric in nature, because (R)-t-Bu-PyBox results in the same major enantiomer.[11]

|

(1) |

Figure 1.

Positive Nonlinear Effect in Formation of Isochroman 3.

In conclusion, we developed a copper-catalyzed alkynylation of 1-aryl isochroman ketals that enables efficient formation of diaryl, tetrasubstituted stereocenters in high enantioselectivities. Application of this strategy to the preparation of other diaryl, tetrasubstituted stereocenters, as well as mechanistic investigations of these reactions, are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Acknowledgement is gratefully made to the National Science Foundation (CAREER CHE 1151364) for support of this research. T.R. thanks the UD Chemistry and Biochemistry Plastino Alumni Undergraduate Research Fellowship program. NMR and other data were acquired at UD on instruments obtained with the assistance of NSF and NIH funding (NSF CHE 0421224, CHE 1229234, CHE 0840401; NIH P20 GM103541, S10 RR02682, 5P30 GM110758).

References

- 1.a Trost BM, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9074–9075. [Google Scholar]; b Sommer MB, Nielsen O, Petersen H, Ahmadian H, Pedersen H, Brosen P, Geiser F, Lee J, Cox G, Dapremont O, Suteu C, Assenza SP, Hariharan S, Nair U. 2011 US 2011/0065938. [Google Scholar]; c Giridhar T, Srinivasulu G, Rao KS. 2011 US 2011/0092719.; d Unterhalt B, Heppert U. Pharmazie. 2002;57:346–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Chinkov N, Warm A, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2957–2961. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Cox N, Uehling MR, Haelsig KT, Lalic G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4878–4882. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Trost B, Toste F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9074–9075. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riant O, Hannedouche J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:873–888. doi: 10.1039/b617746h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For examples of enantioselective alkynylations of ketones, see: Cozzi PG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:2895–2898. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351230. Thompson A, Corley E, Huntington M, Grabowski EJJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:8937–8940. Thompson A, Corley E, Huntington M, Grabowski E, Remenar J, Collum D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:2028–2038. Tan L, Chen C-Y, Tillyer R, Grabowski E, Reider P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:711–713. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990301)38:5<711::AID-ANIE711>3.0.CO;2-W..

- 5.For examples of enantioselective, copper-catalyzed additions, see: Madduri AVR, Harutyunyan SR, Minnaard AJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3164–3167. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109040. Yamasaki S, Fujii K, Wada R, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6536–6537. doi: 10.1021/ja0262582. Wada R, Oisaki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8910–8911. doi: 10.1021/ja047200l..

- 6.a Schmidt F, Stemmler RT, Rudolph J, Bolm C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:454–470. doi: 10.1039/b600091f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Truppo MD, Pollard D, Devine P. Org. Lett. 2007;9:335–338. doi: 10.1021/ol0627909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Goto M, Konishi T, Kawaguchi S, Yamada M, Nagata T, Yamano M. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2011;15:1178–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547. [Google Scholar]; b Wang Z-X, Tu Y, Frohn M, Zhang J-R, Shi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11224–11235. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Braun M, Kotter W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:514–517. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Reisman SE, Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7198–7199. doi: 10.1021/ja801514m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Moquist PN, Kodama T, Schaus SE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7096–7100. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hsiao C-C, Liao H-H, Sugiono E, Atodiresei I, Rueping M. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:9775–9779. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Rueping M, Volla CMR, Atodiresei I. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4642–4645. doi: 10.1021/ol302084q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Meng Z, Sun S, Yuan H, Lou H, Liu L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:543–547. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Benfatti F, Benedetto E, Cozzi PG. Chem. Asian J. 2010;5:2047–2052. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Terada M, Li F, Toda Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:235–239. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Terada M, Yamanaka T, Toda Y. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:13658–13662. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Cui Y, Villafane LA, Clausen DJ, Floreancig PE. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:7618–7626. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Burns NZ, Witten MR, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14578–14581. doi: 10.1021/ja206997e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Witten MR, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:5912–5916. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Maity P, Srinivas HD, Watson MP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17142–17145. doi: 10.1021/ja207585p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Srinivas HD, Maity P, Yap GPA, Watson MP. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:4003–4016. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxocarbenium ions derived from acetals may also impose less steric hindrance in the approach of a nucleophile than their fully substituted counter-parts derived from ketals.

- 11.See Supporting Information.

- 12. CCDC 973167 contains the supplementary cry stallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- 13.19% isolated yield was observed with an achiral catalyst (12 mol % [Cu(MeCN)4]PF6, Et3N, TMSOTf , Et2O, rt, 24 h).

- 14.Karastatiris P, Mikroyannidis JA, Spiliopoulos IK, Kulkarni AP, Jenekhe SA. Macromolecules. 2004;37:7867–7878. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan B-T, Xiang S-K, Wu T, Sun Z-P, Wang B-Q, Zhao K-Q, Shi Z-J. Chem. Commun. 2008:1437–1439. doi: 10.1039/b718998b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell TA, Bode JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18057–18059. doi: 10.1021/ja906514s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Kanazawa Y, Tsuchiya Y, Kobayashi K, Shiomi T, Itoh J.-i., Kikuchi M, Yamamoto Y, Nishiyama H. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:63–71. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Debono N, Djakovitch L, Pinel C. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691:741–747. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Díez J, Gamasa MP, Panera M. a. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:10043–10045. doi: 10.1021/ic061453t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Panera M. a., Díez J, Merino I, Rubio E, Gamasa MP. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:11147–11160. doi: 10.1021/ic901527x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Nakajima K, Shibata M, Nishibayashi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:2472. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a Ahlquist M, Fokin VV. Organometallics. 2007;26:4389–4391. [Google Scholar]; b Díez J, Gamasa MP, Gimeno J, Aguirre A, García-Granda S, Holubova J, Falvello LR. Organometallics. 1999;18:662–669. [Google Scholar]; c Mealli C, Godinho SSMC, Calhorda MJ. Organometallics. 2001;20:1734–1742. [Google Scholar]; d Rodionov VO, Fokin VV, Finn MG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:2210–2215. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girard C, Kagan H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2922–2959. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981116)37:21<2922::AID-ANIE2922>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.