Abstract

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) are the most commonly used scales to test cognitive impairment in Lewy body disease (LBD), but there is no consensus on which is best suited to assess cognition in clinical practice and most sensitive to cognitive decline. Retrospective cohort study of 265 LBD patients [Parkinson’s disease (PD) without dementia (PDnD, N = 197), PD with dementia (PDD, N = 40), and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB, N = 28)] from an international consortium who completed both the MMSE and MoCA at baseline and 1-year follow-up (N = 153). Percentage of relative standard deviation (RSD%) at baseline was the measure of inter-individual variance, and estimation of change (Cohen’s d) over time was calculated. RSD% for the MoCA (21 %) was greater than for the MMSE (13 %) (p = 0.03) in the whole group. This difference was significant only in PDnD (11 vs. 5 %, p < 0.01), but not in PDD (30 vs. 19 %, p = 0.37) or DLB (15 vs. 14 %, p = 0.78). In contrast, the 1-year estimation of change did not differ between the two tests in any of the groups (Cohen’s effect <0.20 in each group). MMSE and MoCA are equal in measuring the rate of cognitive changes over time in LBD. However, in PDnD, the MoCA is a better measure of cognitive status as it lacks both ceiling and floor effects.

Keywords: Parkinson disease, MMSE, MoCA, Dementia with Lewy bodies, Rate of cognitive decline

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common type of neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (10–15 vs. 65 % of cases, respectively) (Aarsland et al. 2008). A clinical diagnosis of DLB can be difficult because of the variability and the overlap with AD and Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PDD). The cognitive profile can vary between AD and DLB patients, with memory problems not necessarily the most prominent feature in DLB (McKeith et al. 2005). Accurate diagnosis and assessment of cognitive abilities is very important for patient management. For example, in PD cognitive decline is associated with reduced function, quality of life, caregiver burden and shorter time to nursing home admission (Temlett and Thompson 2006). Similarly, the prognosis is worse in DLB compared to AD, with shorter time to nursing home admission and death (Oesterhus et al. 2014; Rongve et al. 2014).

Cognitive screening tests should be short and easy to administer, but still sufficiently sensitive to detect both mild and severe impairment, as well as different cognitive domains. Two of the most commonly used cognitive screening scales are the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al. 2005). However, there is lack of consensus about which is best suited to assess cognition in patients with Lewy body disease (LBD; i.e., PD and DLB). Cross-sectional studies suggest that the MoCA is more sensitive than the MMSE in elderly people, AD, PD, Huntington disease and DLB (Gill et al. 2008; Lessig et al. 2012a; Wang et al. 2013). The MoCA’s better sensitivity may be due to lack of ceiling effect, since it is more challenging and contains more attention-executive items than the MMSE.

Few longitudinal studies have explored the rate of cognitive decline in DLB and PDD, and most of them have used only the MMSE. Although findings vary, MMSE rate of decline is similar in DLB and PDD compared with AD (Aarsland et al. 2011a; Breitve et al. 2014), but this may reflect that the MMSE is not sensitive in capturing some DLB-specific cognitive deficits.

Two longitudinal studies have compared the MoCA and MMSE in PD, with one showing the MMSE to be superior (Lessig et al. 2012a) and the other reporting the opposite (Hu et al. 2014). We recently (van Steenoven et al. 2014) reported a formula for conversion from MMSE to MOCA scores in PD but not in LBD. The aims of this analyses were to compare the clinical utility of MoCA and MMSE in both PD and DLB and their sensitivity in detecting cognitive decline over time.

Materials and methods

Population

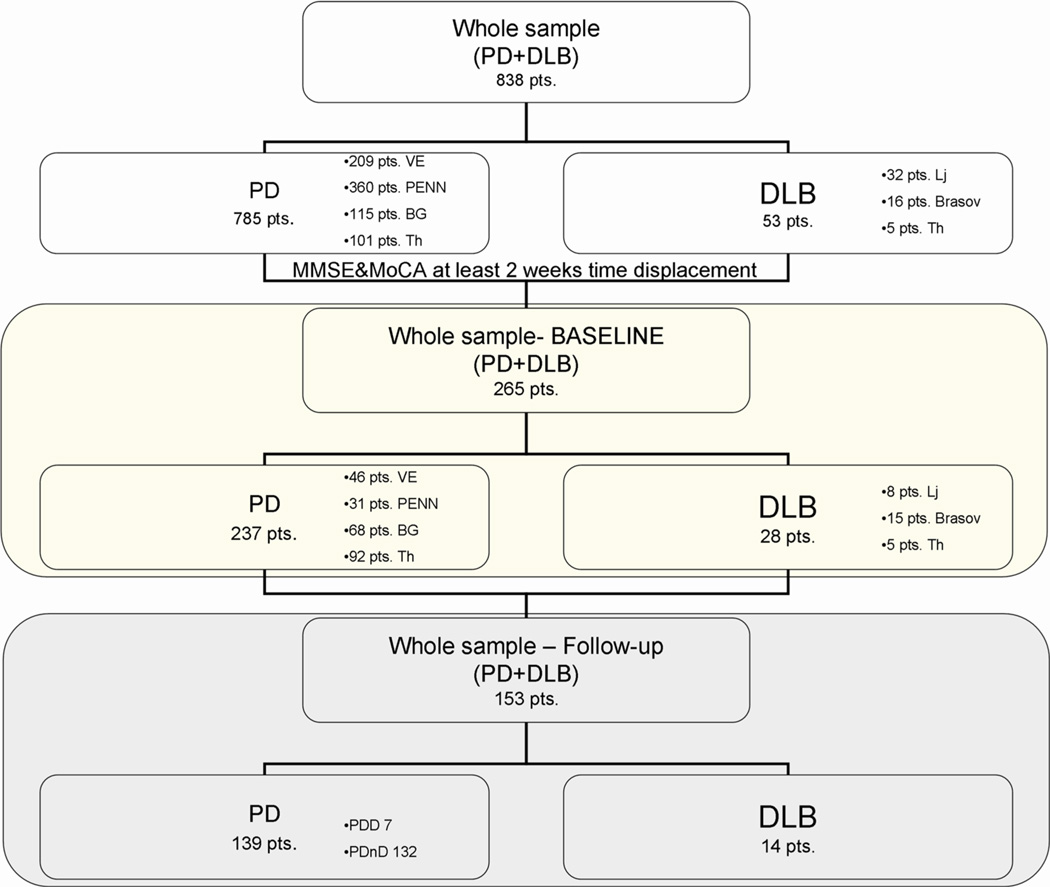

From a total of 838 LBD patients evaluated at six different centers [Venice (IT), Philadelphia (USA), Belgrade (SRB), Thessaloniki (GR), Brasov (RO) and Ljubljana (SLO)] we considered the 265 who completed both the MMSE and MoCA scales within 2 weeks of each other (197 PDnD, 40 PDD and 28 DLB) of which 153 (132 PDnD, 7 PDD and 14 DLB) also performed both scales at 1-year follow-up (FU) (Fig. 1). Demographic variables (age, education, gender) and clinical characteristics (age of onset, disease duration, UPDRS-III score) were collected by neurologists with experience in movement disorders.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram: inclusion criteria for selecting participants. PDD PD with dementia, PDnD PD without dementia

All PD patients were diagnosed according to the UK brain Bank criteria (Gelb et al. 1999). The clinical diagnosis of probable DLB was made according to international consensus criteria (McKeith et al. 2005). Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was calculated (Tomlinson et al. 2010). Patients with a history of deep brain stimulation were excluded in order to minimize observed cognitive change bias.

Cognitive assessment (including MMSE and MoCA scale) was administered and used to identify PDnD versus PDD according to the MDS PDD task force criteria in addition to the clinical interview (Dubois et al. 2007). MMSE and MoCA were administered in a random order across the centers in ON medication state. All patients gave informed written consent before study enrolment. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the local IRB approvals and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statistical analysis

Cross-sectional analysis

After assessing normal distribution across samples using Shapiro–Wilk test, independent unpaired t tests were run to compare continuous demographic and clinical variables among groups. Chi square test was adopted to analyze dichotomous variables. The percentage for the relative standard deviation (RSD%) [(SD/mean) × 100] was calculated to examine inter-individual variance of the MMSE and MoCA within each subgroup at baseline, assuming that greater RSD% indicates better detection of cognitive heterogeneity of the sample (Bland and Altman 1995; Kelley 2007). The MMSE and MoCA RSD% index of each subgroups obtained were further compared by means of Person–Chi square test (Richardson 2011). Moreover in order to evaluate presence of ceiling/floor effect we calculated for each subgroup 25–75 % percentiles. To avoid bias due to different distribution of the two scales, variances of the samples were logarithmically transformed and F-test analysis applied to compare variance ratio between the two scales for each cognitive subgroup. If significant, stepwise linear regression analysis was performed with MMSE or MoCA scores as dependent, and age, LEED, age of onset, UPDRSIII score, education, and disease duration as independent variables. Predictors were included in the multiple regression model if they increased F-value by at least tail probability value of 0.01 and excluded if they increase F-value by less than tail probability value of 0.1. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between the scales.

Longitudinal analysis

Cohen’s effect (d′) was calculated as an estimate of change in MMSE and MoCA (Cohen 1988). Pearson’s correlation between the two scale scores at 1-year follow-up assessment was calculated. Two-way ANOVA with scale (MMSE or MOCA) and baseline cognitive severity subgroups [based on published MoCA cut-offs (Biundo et al. 2014)] as predictors and rate of cognitive decline as dependent factor was carried out. Paired t test and Wilcoxon non parametric test (if normality was not assumed) were used to compare mean annual rate of change between the scales for each cognitive severity subgroup. Additional analyses were performed to check whether clinical–demographic characteristics, such as age, education, baseline MMSE and MoCA score, disease duration, predicted rate of decline on the MMSE or MoCA. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 20.0.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cross-sectional (237 PD and 28 DLB) and longitudinal (139 PD and 14 DLB) cohorts were similar. Compared with PD, DLB patients were older at onset and assessment, had shorter disease duration, less education, and were more cognitively impaired (Table 1, data provided by each sites are displayed in e-Table 1). Moreover PDnD and PDD demographic and clinical characteristics of the cross-sectional (197 PDnD, 40 PDD) and longitudinal (132 PDnD, 7 PDD) cohorts were displayed in e-Table 2.

Table 1.

Mean (±SD) of clinical and demographic characteristics of the total cohort and longitudinal subgroups

| Total cohort | Longitudinal cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD (237 pts.) |

DLB (28 pts.) |

PD (139 pts.) |

DLB (14 pts.) |

|

| M/F | 174/63 | 18/10# | 102/37 | 9/5# |

| Age | 65.27 ± 9.25 | 70.46 ± 8.35** | 65.53 ± 8.95 | 69.00 ± 8.98 |

| Education | 12.09 ± 3.80 | 10.11 ± 3.33* | 12.04 ± 3.66 | 11.00 ± 2.04 |

| Age of disease onset | 55.06 ± 9.91 | 67.75 ± 8.77** | 55.89 ± 10.4 | 65.79 ± 9.38** |

| Disease duration | 10.23 ± 5.16 | 2.71 ± 2.09** | 8.90 ± 5.37 | 2.71 ± 1.54** |

| DAED | 157.40 ± 120.10 | 176.00 ± 39.90 | 123.02 ± 82.34 | NA |

| LEDD | 583.90 ± 386.60 | 542.40 ± 216.90 | 605.75 ± 319.52 | 620.67 ± 236.23 |

| UPDRS-III | 35.81 ± 14.16 | 19.86 ± 8.67** | 43.06 ± 14.54 | 16.29 ± 4.20** |

| MMSE | 27.23 ± 3.38 | 23.18 ± 3.28** | 27.50 ± 2.34 | 22.60 ± 3.85 |

| MoCA | 23.57 ± 4.90 | 20.46 ± 3.01** | 24.53 ± 3.90 | 21.4 ± 1.92** |

UPDRS-III United Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, part III, LEDD Levodopa equivalent dose, DAED dopamine agonist equivalent dose, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment

p < 0.005 unpaired t test

p < 0.001 unpaired t test—(Levene’s test for equality of variance)

p < 0.05, Chi square test

68 % of PD and 100 % of DLB patients were on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine at baseline.

Baseline results

The mean MMSE score (26.80 ± 3.59) was higher than the mean MoCA score (23.24 ± 4.83) in the whole group, as well as in PD (p < 0.001) and DLB specifically (p < 0.001). The MoCA RSD% in the whole study population was significantly greater (21 %) compared with the MMSE (13 %) (p = 0.03) as well as in the PDnD group (5 % for MMSE vs. 11 % for MoCA, p = 0.03). Percentile analysis in this subgroup showed presence of ceiling effect for MMSE but not for MoCA scale (maximum total scores from the 75th percentile). By contrast in PDD and DLB cohorts the RSD% did not differ (Table 2). MMSE and MoCA baseline scores were highly correlated in the whole LBD cohort (r = 0.81, p < 0.0001), as well as in PD (r = 0.83, p < 0.0001), PDnD (r = 0.50, p < 0.0001), PDD (r = 0.75, p < 0.0001) and DLB (r = 0.57, p = 0.002) specifically.

Table 2.

MMSE/MoCA mean (SD), median, range scores, RSD% in the PD and DLB patients

| Mean | SD | RSD% | Median | Minimum | Maximum | 25–75 P | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBD (265) | ||||||||

| MMSE | 26.80* | 3.59 | 13 | 28 | 10 | 30 | 26–29 | p = 0.03 |

| MOCA | 23.24 | 4.83 | 21 | 24 | 7 | 30 | 21–27 | |

| DLB (28) | ||||||||

| MMSE | 23.18* | 3.28 | 14 | 24 | 13 | 29 | 22–25 | p = 0.78 |

| MOCA | 20.46 | 3.01 | 15 | 21 | 14 | 26 | 19–23 | |

| PD (237) | ||||||||

| MMSE | 27.23* | 3.38 | 12 | 28 | 10 | 30 | 27–29 | p = 0.01 |

| MOCA | 23.57 | 4.90 | 21 | 25 | 7 | 30 | 22–27 | |

| PDnD (197) | ||||||||

| MMSE | 28.42* | 1.48 | 5 | 29 | 23 | 30 | 27–30 | p = 0.03 |

| MOCA | 25.22 | 2.88 | 11 | 25 | 17 | 30 | 23–27 | |

| PDD (40) | ||||||||

| MMSE | 21.40* | 4.02 | 19 | 22 | 10 | 29 | 19–24 | p = 0.37 |

| MOCA | 15.43 | 4.70 | 30 | 15 | 7 | 26 | 12–18 |

LBD Lewy body disorders, DLB dementia with Lewy body, PD Parkinson disease, PDnD Parkinson without dementia, PDD Parkinson with dementia, MMSE Mini Mental State Examination, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment

χ2 = Chi square test within subgroup RSD percentage comparison in MMSE and MoCA; p significant RDS% differences between MMSE and MoCA;

= significant F-test variance ratio between MMSE and MoCA baseline score in each subgroup at p < 0.001; 25–75 p = MMSE and MoCA scores included between the 25th and 75th percentile

Stepwise linear regression analyses showed that none predictors included in the model survived for DLB and PDD subgroups. In PD and PDnD subgroups age, education and LEDD explained a relatively small proportion of the variance for both scales (23 % for MoCA and 14 % for MMSE in PD and 19 % for MoCA and 15 % for MMSE in PDnD) (see e-Table 3 for further details).

Longitudinal results

There was no difference in MMSE and MoCA change over 1 year. More specifically in the whole PD mean (SD) difference at 1-year follow-up was −0.33 (1.14) for MMSE and −0.30 (1.32) for MoCA (d′ = −0.06). In DLB the mean change was −0.98 (1.07) for MMSE and −1.04 (1.32) for MoCA (d′ = −0.13). Similar results were observed in each PD subgroup (see Table 3; e-Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Estimation of change comparison (d′) between MMSE and MoCA at 1 year follow up

| N | Mean difference T1–T0 |

SD | Mean difference T1–T0 |

SD | Score | MMSE versus MoCA T1–T0 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | MoCA | Group difference | Cohen’s effect | ||||

| PD | 237 | −0.33 | 1.14 | −0.30 | 1.32 | −0.03 | −0.066 |

| PDnD | 197 | −0.36 | 1.13 | −0.32 | 1.39 | −0.04 | −0.091 |

| PDD | 40 | −0.20 | 1.18 | −0.23 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.051 |

| DLB | 28 | −0.98 | 1.07 | −1.04 | 1.32 | 0.06 | 0.139 |

DLB dementia with Lewy body, PD Parkinson disease, PDnD Parkinson without dementia, PDD Parkinson with dementia

MMSE and MoCA follow-up scores were highly correlated in the whole LBD cohort (r = 0.81, p < 0.001), as well as in PD (r = 0.79, p < 0.0001), PDnD (r = 0.71, p < 0.0001), PDD (r = 0.98, p < 0.0001) and DLB (r = 0.74, p = 0.003) specifically.

Two-way ANOVA with baseline cognitive severity and cognitive scales as predictors, and cognitive rate of decline as dependent factor, showed an effect of baseline scale score in explaining decline over time (p = 0.003) in the whole LBD sample with a trend for faster rate of decline in more severely impaired patients. This effect was significant in the PD (p < 0.004), but not in the DLB (p < 0.172), cohort.

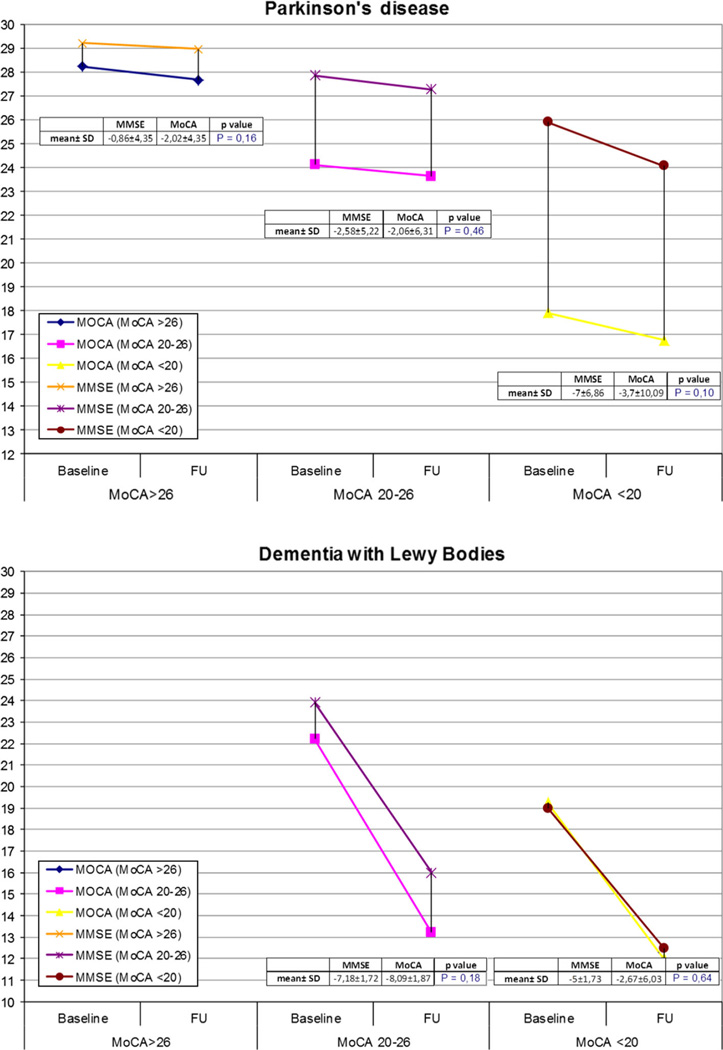

When we divided patients based on the severity of cognitive impairment [MoCA <20 (N = 40), 20–26 (N = 126), >26 (N = 71) for PD; MoCA <20 (N = 8), 20–26 (N = 20) for DLB] we did not find differences in MMSE and MoCA rate of change in the two diseases. However, we found a trend for greater MoCA versus MMSE change in subjects with milder cognitive impairment (i.e., MoCA >26) (−2.02 ± 4.35 in MoCA vs. −0.86 ± 4.35 for MMSE in PD, p = 0.16; and −8.09 ± 1.87 for MoCA vs. −7.18 ± 1.72 for MMSE in DLB, p = 0.18). Conversely, there was an opposite trend for greater MMSE versus MoCA decline over time in PD with severe cognitive deficits (MoCA cut-off <20) (−7.00 ± 6.86 for MMSE vs. −3.70 ± 10.9 for MoCA p = 0.1) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean percentage rate of change of MMSE and MoCA in PD and DLB group according to MoCA cognitive severity at baseline. FU follow up

Discussion

In this study we found that the MMSE and MoCA are not equivalent in assessing cognitive performance in LBD, as the MoCA showed greater variance compared with the MMSE in non-demented PD patients. However, there was no difference between the two scales in the 1-year rate of cognitive change both for the whole group, as well as PD and DLB. A second finding was that clinical and demographic variables explained only a small portion of the variance in the MMSE and MoCA scores in PD and non-demented PD (23 % for MoCA and 14 % for MMSE in PD and 19 % for MoCA and 15 % for MMSE in PDnD). Therefore, it can be inferred that the variability in scale performance observed likely reflects core differences in their characteristics.

The MMSE was initially developed to detect cognitive deficits in AD, which are characterized by difficulties in episodic memory (progressing from recent to remote) and language, and less frequently accompanied by word-finding, executive function, and visuospatial ability deficits in early disease (Koedam et al. 2010). Conversely, the MoCA investigates additional cognitive domains which are also affected in PD, in particular fronto-striatal (i.e., executive-attentional abilities) and visuospatial abilities (Owen 2004).

If it is true that MMSE captures relatively more “posterior” defects and the MoCA more “executive” dysfunction, our results of equal variance between MMSE and MoCA in DLB suggest that the DLB cognitive profile is characterized by both frontal and posterior involvement.

There was a non-significant trend towards greater MoCA variance in PDD (30 %) compared with DLB (15 %). As expected, motor symptoms were also less severe in DLB than PDD (UPDRS-III score of 40.00 ± 14.81 in PDD vs. UPDRS-III score of 19.86 ± 8.67 in DLB). It could be that motor severity affects MoCA performance more than MMSE, since MoCA contains more subtests requiring motor skills involvement, such as the trail making test, more complex construction test and the sustained attention test. Further analysis in this regard is needed.

Interestingly we found a gradually higher variability of MMSE and MoCA in PD with more severely impaired cognition. In particular we observed the lowest RSD percentage (5 %) expressed by MMSE compared with the MoCA in non-demented PD. This is most likely due to a ceiling effect (the 25th–75th percentile was 27–30 for MMSE scores compared with 23–27 for the MoCA) (Chou et al. 2010; Zadikoff et al. 2008). We found the highest RSD% expressed by MoCA in PDD (30 %). These results corroborate previous findings that MoCA is more sensitive than the MMSE in detecting early cognitive changes in PD (Biundo et al. 2014; Chou et al. 2014; Dalrymple-Alford et al. 2011; Hoops et al. 2009). Moreover, MoCA did not show a floor effect, suggesting that this scale, as well as the MMSE, may be a valid instrument to detect dementia in PD.

We found that dopaminergic therapy dose (i.e., LEDD) was associated with MoCA, but not MMSE score in PD. Multiple lines of research have demonstrated the key role of dopamine neuromodulation on mental abilities and that this is mediated by the activity of prefrontal neurons. This finding further highlights the importance of assessing PD global cognitive status always in the ON state.

Finally, we observed that age and education both impact MMSE and MoCA performance in non-demented PD. This is not surprising for the MMSE, because we used uncorrected data. Findings that fewer years of education and older age are associated with worse cognition in MoCA scale are consistent with previous studies (Glatt et al. 1996; Hu et al. 2014; Hughes et al. 2000; Levy et al. 2002) and further highlight the importance of using age and education specific normative data. In this regard alternative or education-adjusted norms have been proposed for the MoCA scale according to the age stage and to the different languages (Malek-Ahmadi et al. 2015; Santangelo et al. 2015).

The longitudinal analyses did not show differences between the MMSE and MoCA in rate of cognitive decline at 1-year follow-up. Conversely previous studies in PD were inconsistent and showed better performance either for MoCA (Hu et al. 2014; Kandiah et al. 2014) or MMSE (Lessig et al. 2012b) probably due to different sample disease duration (early stage favoring MoCA). Our findings for a trend of higher MoCA sensitivity in detecting cognitive decline in individuals with milder cognitive impairment can be interpreted in favour of MoCA. However further studies with longer follow-up period and broader range of disease duration are needed.

We recognize that the small DLB sample size might have hampered our ability to fully measure variance expressed by both scales. Moreover, the specialized nature of recruitment centres might have reduced the representativeness of the sample. Finally, the observation period was short, and measuring cognitive decline over a longer period may provide a more accurate estimate of sensitivity to change (Aarsland et al. 2004, 2011b). This was supported by the fact that some patients showed improvement in both scales scores (29/153 for MMSE and 26/153 for MoCA), also observed in another study (Hu et al. 2014) which is consistent with fluctuations in cognitive performance or practice effects in some patients. We believe this was not due to the long-term effect of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in some patients as it is known that treatment benefit on cognition is minor in both diseases (Wang et al. 2015). Moreover patients were likely in these medications for some time already at baseline, it is unlikely to expect a continued improvement in cognition. In addition since there was no research common protocol there may be minor differences between centres regarding the timing of testing and or the use of concomitant medications that we couldn’t account for. Finally, the PD and DLB diagnostic criteria may not discriminate two completely distinct populations (McKeith et al. 2005; Nelson et al. 2010; Verghese et al. 1999) thus blurring between-group differences.

In conclusion our results show that both MMSE and MoCA are suitable scales to assess cognitive abilities in PD and DLB. However, given the greater variability and the lack of ceiling and floor effects, we believe MoCA is superior for cognitive screening. Additional studies with longer follow-up are needed to confirm our findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Pablo Martinez-Martin for helping with statistical analysis

Funding This working group is funded by the Research Council of Norway, Norway under the aegis of JPND.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00702-016-1517-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards

All authors gave final approval of this version of the manuscript to be published. We can assure that there is no one else who fulfils the criteria but has not been included as an author.

Conflict of interest The authors have no competing interest to declare.

References

- Aarsland D, Andersen K, Larsen JP, Perry R, Wentzel-Larsen T, Lolk A, Kragh-Sorensen P. The rate of cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1906–1911. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland D, Beyer MK, Kurz MW. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:676–682. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283168df0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland D, Muniz G, Matthews F. Nonlinear decline of minimental state examination in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011a;26:334–337. doi: 10.1002/mds.23416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland D, Muniz G, Matthews F. Nonlinear decline of minimental state examination in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011b;26:334–337. doi: 10.1002/mds.23416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biundo R, Weis L, Facchini S, Formento-Dojot P, Vallelunga A, Pilleri M, Antonini A. Cognitive profiling of Parkinson disease patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Comparing two methods of clinical measurement: a personal history. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(Suppl 1):S7–S14. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.supplement_1.s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitve MH, Chwiszczuk LJ, Hynninen MJ, Rongve A, Bronnick K, Janvin C, Aarsland D. A systematic review of cognitive decline in dementia with Lewy bodies versus Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6 doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0053-6. 53-014-0053-6 (eCollection 2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou KL, Amick MM, Brandt J, Camicioli R, Frei K, Gitelman D, Goldman J, Growdon J, Hurtig HI, Levin B, Litvan I, Marsh L, Simuni T, Troster AI, Uc EY Parkinson Study Group Cognitive/Psychiatric Working Group. A recommended scale for cognitive screening in clinical trials of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2501–2507. doi: 10.1002/mds.23362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou KL, Lenhart A, Koeppe RA, Bohnen NI. Abnormal MoCA and normal range MMSE scores in Parkinson disease without dementia: cognitive and neurochemical correlates. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:1076–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple-Alford JC, Livingston L, MacAskill MR, Graham C, Melzer TR, Porter RJ, Watts R, Anderson TJ. Characterizing mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:629–636. doi: 10.1002/mds.23592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Burn D, Goetz C, Aarsland D, Brown RG, Broe GA, Dickson D, Duyckaerts C, Cummings J, Gauthier S, Korczyn A, Lees A, Levy R, Litvan I, Mizuno Y, McKeith IG, Olanow CW, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Tolosa E, Emre M. Diagnostic procedures for Parkinson’s disease dementia: recommendations from the movement disorder society task force. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2314–2324. doi: 10.1002/mds.21844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill DJ, Freshman A, Blender JA, Ravina B. The Montreal cognitive assessment as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1043–1046. doi: 10.1002/mds.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt SL, Hubble JP, Lyons K, Paolo A, Troster AI, Hassanein RE, Koller WC. Risk factors for dementia in Parkinson’s disease: effect of education. Neuroepidemiology. 1996;15:20–25. doi: 10.1159/000109885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoops S, Nazem S, Siderowf AD, Duda JE, Xie SX, Stern MB, Weintraub D. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1738–1745. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34b47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MT, Szewczyk-Krolikowski K, Tomlinson P, Nithi K, Rolinski M, Murray C, Talbot K, Ebmeier KP, Mackay CE, Ben-Shlomo Y. Predictors of cognitive impairment in an early stage Parkinson’s disease cohort. Mov Disord. 2014;29:351–359. doi: 10.1002/mds.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TA, Ross HF, Musa S, Bhattacherjee S, Nathan RN, Mindham RH, Spokes EG. A 10-year study of the incidence of and factors predicting dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2000;54:1596–1602. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.8.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandiah N, Zhang A, Cenina AR, Au WL, Nadkarni N, Tan LC. Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the screening and prediction of cognitive decline in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:1145–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K. Sample size planning for the coefficient of variation from the accuracy in parameter estimation approach. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:755–766. doi: 10.3758/bf03192966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koedam EL, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YA. Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: more than age alone. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1401–1408. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessig S, Nie D, Xu R, Corey-Bloom J. Changes on brief cognitive instruments over time in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012a;27:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/mds.25070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessig S, Nie D, Xu R, Corey-Bloom J. Changes on brief cognitive instruments over time in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012b;27:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/mds.25070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy G, Schupf N, Tang MX, Cote LJ, Louis ED, Mejia H, Stern Y, Marder K. Combined effect of age and severity on the risk of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:722–729. doi: 10.1002/ana.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek-Ahmadi M, Powell JJ, Belden CM, O’Connor K, Evans L, Coon DW, Nieri W. Age- and education-adjusted normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in older adults age 70–99. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2015;22:755–761. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2015.1041449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M Consortium on DLB. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Cooper G, Xu LO, Smith CD, Markesbery WR. Low sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol. 2010;257:359–366. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5324-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterhus R, Soennesyn H, Rongve A, Ballard C, Aarsland D, Vossius C. Long-term mortality in a cohort of home-dwelling elderly with mild Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38:161–169. doi: 10.1159/000358051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM. Cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: the role of frontostriatal circuitry. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:525–537. doi: 10.1177/1073858404266776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JTE. The analysis of 2 × 2 contingency tables—Yet again. Stat Med. 2011;30:890. doi: 10.1002/sim.4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongve A, Vossius C, Nore S, Testad I, Aarsland D. Time until nursing home admission in people with mild dementia: comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:392–398. doi: 10.1002/gps.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo G, Siciliano M, Pedone R, Vitale C, Falco F, Bisogno R, Siano P, Barone P, Grossi D, Santangelo F, Trojano L. Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in an Italian population sample. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1995-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temlett JA, Thompson PD. Reasons for admission to hospital for Parkinson’s disease. Intern Med J. 2006;36:524–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2649–2653. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steenoven I, Aarsland D, Hurtig H, Chen-Plotkin A, Duda JE, Rick J, Chahine LM, Dahodwala N, Trojanowski JQ, Roalf DR, Moberg PJ, Weintraub D. Conversion between Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and Dementia Rating Scale-2 scores in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1809–1815. doi: 10.1002/mds.26062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Lipton RB. Validity of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 1999;53:1974–1982. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CS, Pai MC, Chen PL, Hou NT, Chien PF, Huang YC. Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-Mental State Examination performance in patients with mild-to-moderate dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer’s disease, and normal participants in Taiwan. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:1839–1848. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HF, Yu JT, Tang SW, Jiang T, Tan CC, Meng XF, Wang C, Tan MS, Tan L. Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:135–143. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadikoff C, Fox SH, Tang-Wai DF, Thomsen T, de Bie RM, Wadia P, Miyasaki J, Duff-Canning S, Lang AE, Marras C. A comparison of the mini mental state exam to the Montreal cognitive assessment in identifying cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:297–299. doi: 10.1002/mds.21837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.