Abstract

Two-dimensional materials have become a major focus in materials chemistry research worldwide with substantial efforts centered on synthesis, property characterization, and technological application. These high-aspect ratio sheet-like solids come in a wide array of chemical compositions, crystal phases, and physical forms, and are anticipated to enable a host of future technologies in areas that include electronics, sensors, coatings, barriers, energy storage and conversion, and biomedicine. A parallel effort has begun to understand the biological and environmental interactions of synthetic nanosheets, both to enable the biomedical developments and to ensure human health and safety for all application fields. This review covers the most recent literature on the biological responses to 2D materials and also draws from older literature on natural lamellar minerals to provide additional insight into the essential chemical behaviors. The article proposes a framework for more systematic investigation of biological behavior in the future, rooted in fundamental materials chemistry and physics. That framework considers three fundamental interaction modes: (i) chemical interactions and phase transformations, (ii) electronic and surface redox interactions, and (iii) physical and mechanical interactions that are unique to near-atomically-thin, high-aspect-ratio solids. Two-dimensional materials are shown to exhibit a wide range of behaviors, which reflect the diversity in their chemical compositions, and many are expected to undergo reactive dissolution processes that will be key to understanding their behaviors and interpreting biological response data. The review concludes with a series of recommendations for high-priority research subtopics at the “bio-nanosheet” interface that we hope will enable safe and successful development of technologies related to two-dimensional nanomaterials.

1. Introduction

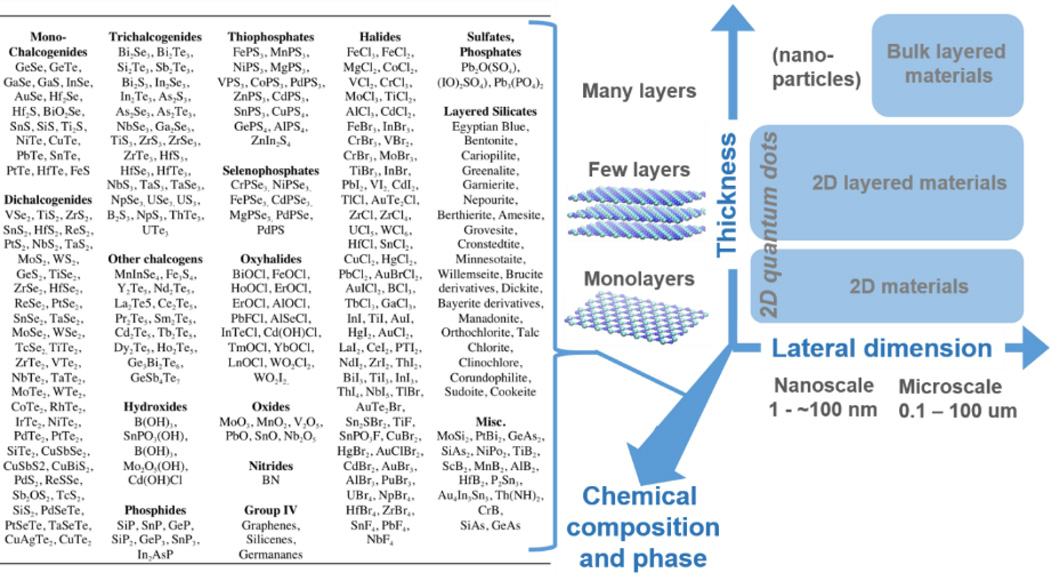

The class of two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials is large and diverse – encompassing monolayer carbons to chalcogenides to layered silicate minerals (Fig. 1). The isolation of graphene1, 2 and the demonstration of an indirect to direct band gap transition in monolayer MoS23, 4 among other findings, have made 2D materials research one of the most exciting fields in science today. For the purposes of this review, we define a 2D material as a single sheet of covalently bonded atoms, arranged in one to several atomic layer planes, of extended lateral dimension that form a high-aspect-ratio (>10) sheet- or plate-like solid. The review scope also includes “2D layered materials” which we define as sheet-like solids that consist of several such covalently bonded layers separated by van der Waals (vdW) gaps, as well as “layered materials”, which are bulk substances with lamellar crystal structures that consist of many such covalent layers and associated vdW gaps. For convenience the broad material class will sometimes be referred to in this review using the abbreviated phrase: “2D materials”.

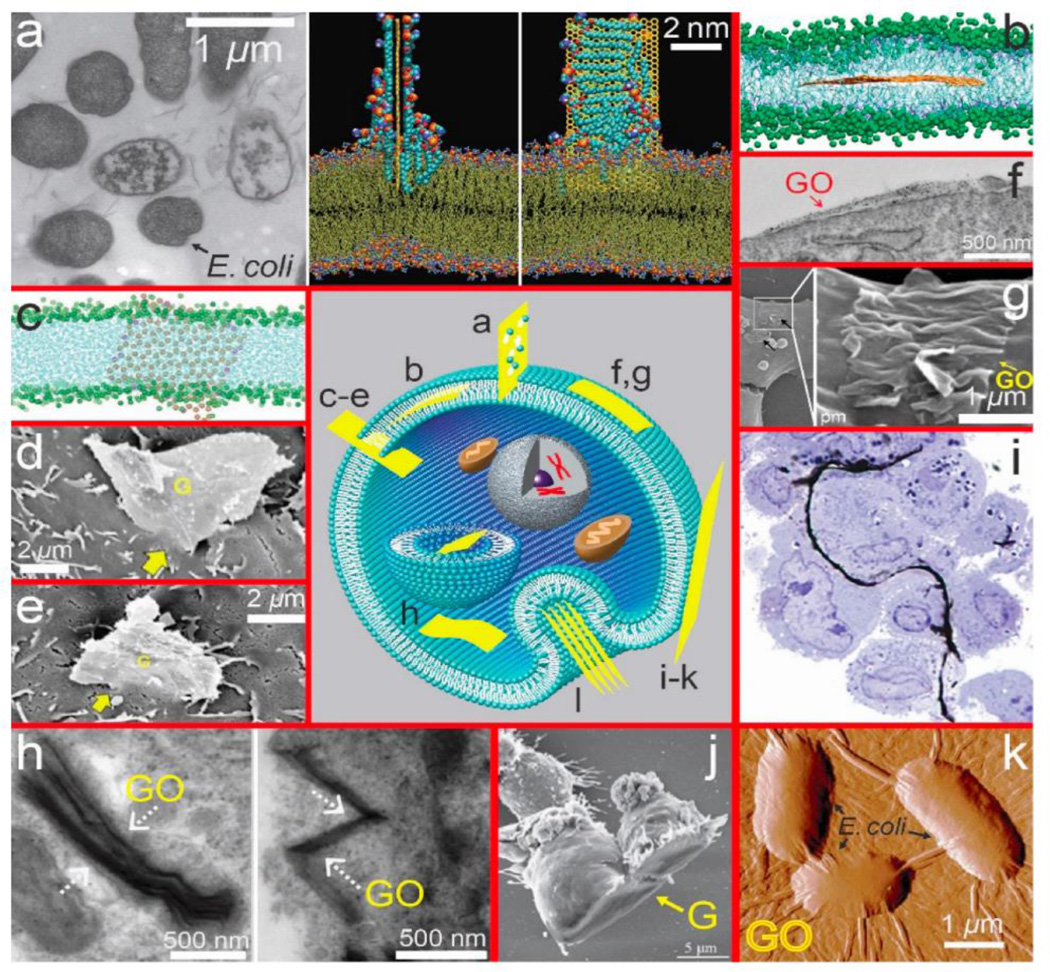

Figure 1.

Diversity in chemistry and morphology of 2D and layered materials. Right: Classification of 2D materials used in this review. Morphology (thickness and lateral dimension) together with chemical composition and phase are co-determinants of biological and environmental behavior. Left: Examples of 2D and layered material compositions, illustrating the high degree of chemical diversity.

The current rate of innovation in 2D materials is very high, but it is important to recognize that this material class is not new to science or industry.5–12 Chalcogenide, oxide, and graphitic layered materials already find applications in batteries as intercalation electrodes.13 Boron nitride is used as a lubricant and as a cosmetic additive that imparts optical luster or “shine”. The chalcogenides are semiconductors and find use in thermoelectric devices13 and some oxide layered materials exhibit electrochromic properties, changing color upon electrochemical intercalation.13 MoS2 has been in use for well over a century as a solid industrial lubricant13 and a catalyst.14 The layered mineral, bentonite or montmorillonite, is used as an adsorbent in applications such as cat litter and the packing of nuclear fuels – it is also used as a food additive, giving yogurt its smoothness. These applications have generated considerable knowledge and experience in the environmental health and safety issues for layered materials. While that experience can inform the 2D material field, the complexity and diversity of these emerging materials (see Fig. 1), together with their very rapid rate of development, will require a much more systematic and comprehensive approach to ensure their safety.

1.1 The importance of biological and environmental interactions

Much of the current work on 2D materials focuses on basic synthesis, or the characterization of fundamental electronic, photonic, and catalytic behaviors.15 One may ask what the motivation is for studying behavior in biological systems and the natural environment? First, 2D materials are being actively explored for applications in biology16 and the environment,17 and we anticipate these application areas will grow, much in the same way that applications for carbon nanotubes grew far beyond their initial application area of electronic devices as the field matured. Secondly, the study of biological and environmental interactions forms the scientific basis for understanding and managing development risks, which is equally important for biomedical and non-biomedical technologies. The latter inevitably lead to unintended human exposures and environmental releases both from R&D (research and development) activities and larger-scale nano-manufacturing. In our experience, environmental health and safety (EHS) issues are typically raised by parties outside of science, and an early, proactive approach to risk characterization within the scientific community can benefit all parties by reducing the uncertainties that become barriers to investment and permitting needed for large-scale development and commercialization. One can argue that early-stage research on EHS implications should be an essential task along the development pathway for all new chemical and materials-based technologies, and the 2D material field, as a subset of the larger nanotechnology field, should be a high priority for this type of research over the next decade.

1.2 Scope of review and diversity of 2D materials

This review focuses on emerging 2D and layered materials “beyond graphene”. This choice was made because the graphene field has already been the subject of several detailed reviews,18–20 and where the present review does refer to graphene data or behaviors, it is done to inform or guide the thinking on the other 2D materials. We also choose to cover both monolayer (2D) and multilayer (2D layered) forms, as both types will likely be fabricated and commercialized at large scale leading to human and environmental exposures. Relatively little is known about plate-like material interactions with biological systems, and even the thicker multilayer nanomaterials (< 100 nm) may show new and interesting modes of interaction worthy of scientific attention. This review therefore considers all plate-like, high-aspect-ratio (>10) materials with at least one dimension less than about 100 nm (in correspondence with the US federal government definition of nanoscale materials). Where data on the 2D versions are lacking, the review will offer relevant information on bulk lamellar materials, which are often precursors for 2D materials, to give insight into the fundamental chemistry.

A major challenge for the field and for this review is the sheer diversity of this material class (Fig. 1). The numerous chemical compositions and atomic configurations, when crossed with the different physical forms (Fig. 1) lead to an enormous set of new 2D materials for potential study. It will be obvious to readers that understanding biological interactions or quantifying risks by the brute force in vivo testing of all relevant 2D materials is not a practical path forward. There is strong motivation to use fundamental materials chemistry and physics to classify the materials into categories to prioritize research and generalize the results of that research wherever possible. Toward this goal, the present review proposes a framework for relating biological responses to fundamental 2D materials chemistry and physics, which we believe will promote a more systematic approach for the 2D material field going forward.

In the remainder of this review, Section 2 gives background information on synthesis, processing and exposure, while Section 3 reviews the available data on biological interactions. Section 4 outlines a proposed framework for the systematic study of biological interactions grounded in materials chemistry and physics, while Section 5 focuses on material behavior in the natural environment. Our conclusions and recommendations are briefly summarized in Section 6.

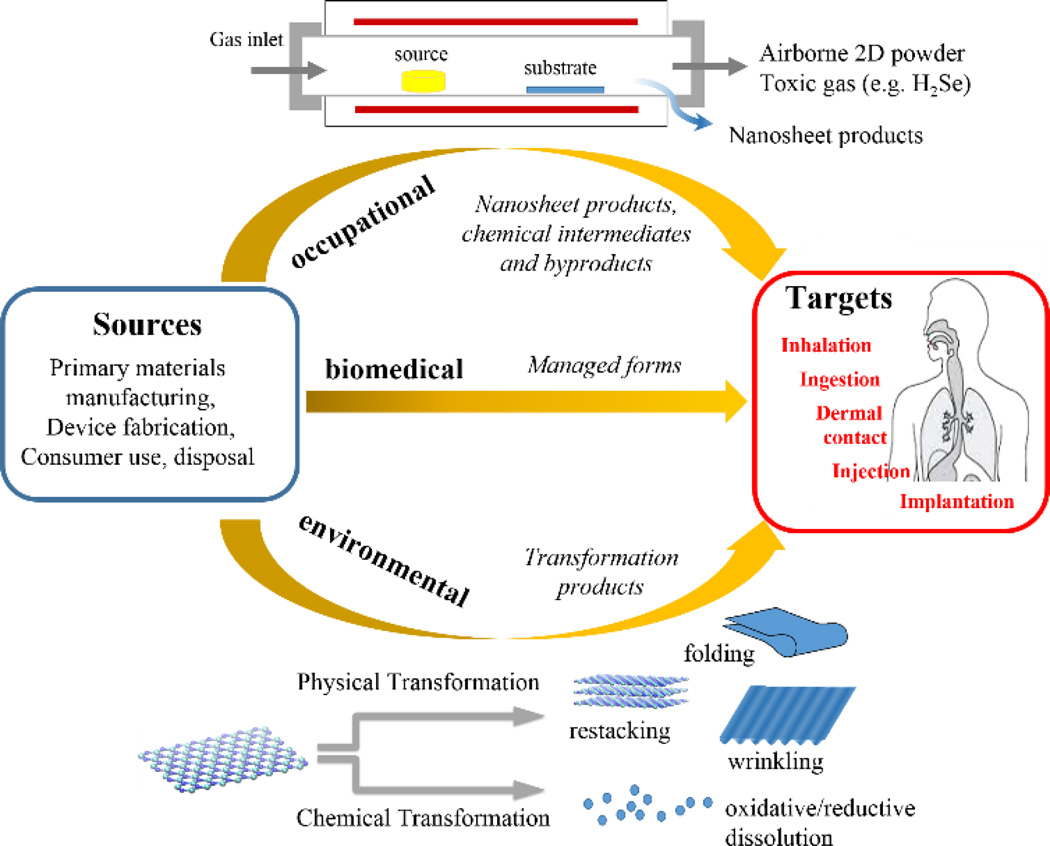

2. Fabrication methods, processing and exposure potential

A central paradigm in toxicology is that risk = hazard (i.e. toxicity) x exposure. Modern technology makes use of countless hazardous substances, for which risk is adequately managed by controlling exposure. For the 2D materials field it will be important to understand and anticipate potential exposures as a guide to safe processing, and in order to set research priorities in the area of toxicity evaluation. In general, human exposures are occupational, environmental, or biomedical, as shown in Fig. 2. Occupational exposures are occurring now for R&D workers and will become increasingly important for workers in nano-manufacturing industries as the field evolves. In occupational settings workers are typically exposed to materials in their as-produced form, or to manufacturing intermediates or byproducts (see below), and the importance of these exposures provides motivation for studying the biological interactions of primary 2D materials in their as-produced form. Environmental exposures, in contrast, occur after the uncontrolled release of materials, which often undergo chemical transformation to other forms before returning to humans through air, food, or water (see Section 5). Biomedical exposures are potentially important, but occur in more controlled settings, and their management is already an integral part of drug and biomedical device development.16 As a first step, it will be useful to briefly consider the most common 2D material synthesis and processing methods that determine the nature of the current and near-term exposures to researchers and process developers.

Figure 2.

Exposure types and pathways for emerging 2D nanomaterials. Most behaviors and issues are similar to those for particulate nanomaterials,21 but there are also distinctive 2D behaviors as shown here, such as physical transformations by folding, wrinkling, and restacking, and the importance of hazardous chemical byproducts and reductive dissolution processes associated with the particular chemical compositions of some important inorganic nanosheet materials.

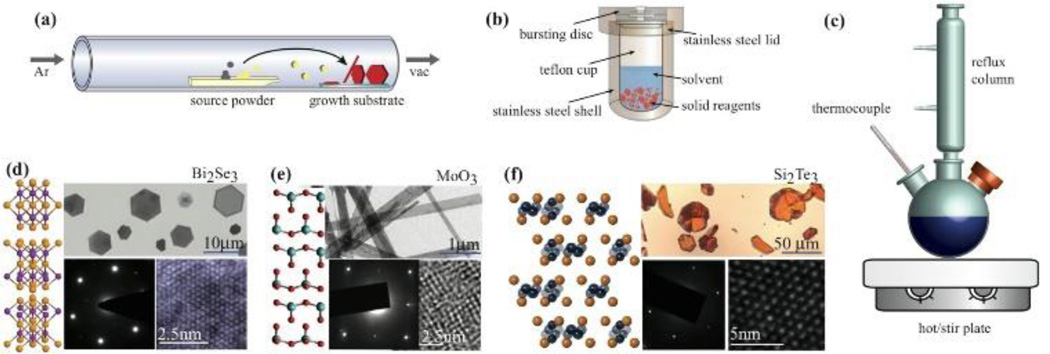

Several excellent reviews cover synthesis methods for 2D materials including graphene-based materials, oxides, and chalcogenides.22–25 The very different types of chemical bonding among oxides, halides, nitrides, and chalcogenides result in very different melting points and vapor pressures, which call for different synthesis approaches. While there are a variety of synthetic techniques, most can be categorized as either (i) solution phase (wet chemical) or (ii) vapor phase (Fig. 3). It remains a challenge to directly synthesize many materials in true monolayer form; however, graphene, MoS2,26 and some of the other transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) can be synthesized as high quality monolayer sheets.27 Few-layer materials can often be generated through exfoliation either after synthesis of a layered parent material or through exfoliation of a naturally occurring bulk layered powder.

Figure 3.

Common synthetic routes to 2D materials. (a) Vapor-phase synthesis, (b) solvothermal/hydrothermal solution synthesis, (c) colloidal solution-based growth. (d) Example Bi2Se3 plates (1–5nm thick) synthesized through solvothermal growth.30 Adapted with permission from ref. 30. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (e) MoO3 nanoribbons synthesized through hydrothermal growth.32 Adapted with permission from ref. 32. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (f) vapor-phase synthesized silicon telluride, Si2Te3.33 Adapted with permission from ref. 33. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

2.1 Solution-based growth

Wet chemical approaches can be used to synthesize 2D materials with thicknesses ranging from the monolayer to hundreds of layers28, 29 and have several advantages. Reaction temperatures are much lower than in vapor-phase routes, and the products can exhibit exceptional uniformity and low defect density. Materials can be doped during growth by addition of other reagents, and the material surface can be capped using ligand chemistry for surface modification and protection.27, 30, 31 Solution-based methods may become more prevalent as 2D material technologies move into the commercialization phase because they are often easily translated into larger-scale manufacturing processes. By selection of environmentally benign precursors and solvents, solution-based methods can be adapted to adhere to principles of green chemistry and manufacturing.27

A traditional wet-chemical approach to chalcogenides involves hydrothermal or solvothermal growth (Fig. 3b). In a typical reaction, the precursors, solvent, and a reducing agent are sealed in a Teflon-lined steel autoclave (Fig.3b) and held at modest temperatures (< 250°C) for hours to days.31, 34–36 Materials synthesized in this manner tend to be thinner (contain fewer layers) than some other methods. Examples of layered Bi2Se3 synthesized solvothermally (1–5 layers) and MoO3 synthesized hydrothermally (~10nm thick) are shown in Fig. 3d and 3e, respectively.30, 32

Colloidal synthesis (Fig. 3c) is a well-established technique for fabrication of chalcogenide and oxide nanomaterials.27 It can also be used to obtain large platelets of layered materials with lateral dimensions ranging from nanometers to ~0.5 micron.27, 37 An excellent review by Han et al. details the variety of wet chemical routes.27 Layered materials are generated through either injection of a cold solution of precursor chemicals into a hot solvent, similar to other colloidal synthetic routes, or through a one-pot route where precursors are combined and heated (up to 320 °C). Recently, Yoo et al.38 showed a novel colloidal route to generate monolayer dichalcogenides such as TiS2, HfS2, and ZrS2 through a technique referred to as “diluted chalcogen continuous influx”. In this method, one controls the rate of delivery of a chalcogen source (such as H2S or CS2) to a transition metal halide precursor in solution. The rate of chalcogen influx is controlled to be slow enough to favor lateral (2D) growth over 3D growth. Large sheets of 0.2–0.5 µm in lateral dimension can be grown directly from solution.38

2.2 Vapor-phase growth

Vapor phase growth of 2D materials yields large, high quality single crystals of oxide and chalcogenide materials with morphologies ranging from nanoribbons to plates to monolayers.23, 39, 40 An excellent review of the current state of the art can be found in Chhowalla et al.15 In a typical vapor-phase process (Fig. 3a), source powder(s) or molecular precursor in solution are heated. A carrier gas (e.g. argon, nitrogen, or forming gas) transports the vapor-phase precursors downstream to substrates that are placed in a region of appropriate temperature for nucleation of the layered or 2D material. Optimization of substrate choice, molecular precursors, and reaction geometry can facilitate growth of monolayers. An example of a quartz tube setup for vapor-phase growth is shown in Fig. 3a along with Si2Te3 generated through large area vapor-solid growth shown in Fig. 3f.33

2.3 Exfoliation

Exfoliation refers to a class of natural or synthetic processes in which thin flakes are derived from bulk materials either through surface shedding or bulk splitting into sheet-like fragments. In contrast to the growth-based methods above, exfoliation is a top-down assembly method that is primarily physical, though chemical driving forces are sometimes used to drive the physical separation. When used for 2D material synthesis, the precursors are most commonly bulk layered materials, but can also be multilayer products of the above growth processes. Exfoliation has long been used to prepare thin samples for transmission electron microscopy,41, 42 and happens naturally in the environment with rock weathering of layered materials.43

To exfoliate a layered material, some external or internal driving force is needed to overcome or weaken the van der Waals forces between adjacent layers. This can proceed mechanically through friction or shear forces, or chemically through intercalation, where the driving force is provided by the free energy of the intercalation reaction or by electrochemical energy added externally to drive ion intercalation. Exfoliated sheets must typically be stabilized to prevent aggregation and re-stacking using surfactants, polymers, solvents, or liquid-liquid interfaces that trap and stabilize the exfoliated sheets.15, 44–46

The isolation of graphene from graphite using scotch tape was the original spark that ignited interest in 2D materials. This type of dry mechanical exfoliation suffers from low-yield and contaminates monolayer surfaces with the adhesive polymer, but has high reproducibility and is quite suitable for making single devices for research purposes and works for all layered materials.1, 2, 47 Recently, large-area mechanical exfoliation has been demonstrated in MoS2 by exploiting the chemical affinity of sulfur to gold. The chalcogenide is deposited on a gold substrate; top layers are removed by thermal adhesive tape leaving behind a large monolayer.48 The limitations on throughput can be overcome by exfoliation in the liquid phases.15, 45, 46, 49 In general, direct sonication of a layered host is carried out in a solvent chosen to stabilize the exfoliated sheets and sometimes selected based on matching surface tension to solid surface energies. While this method can partially exfoliate chalcogenide and oxide systems into few-layer materials, it does not typically provide high yields of the monolayer form. Exfoliated chalcogenides can also be stabilized in solution against reaggregation with ionic surfactants such as sodium cholate46 or alkyl-trichlorosilanes, which form self-assembled monolayers on the chalcogenide surface.50 Layered silicates and double layered hydroxides can be exfoliated through a number of routes including ion exchange and swelling of parent compounds.15, 49, 51

Electrochemical exfoliation has been used for several decades for exfoliation and restacking of layered materials to generate novel compounds.13, 22 It proceeds through electrochemical insertion of an ion (such as Li+) into the host crystal.

| (1) |

| (2) |

This destabilizes the crystal while also inducing a phase change (Eq. 1). Placing the intercalated material in polar solvents forces hydrolysis of the lithiated species and formation of single-sheet colloidal suspensions which can also be used as-produced or restacked through sandwiching with other materials.13, 52, 53 The yield of this method is nearly 100% but requires high temperatures, long reaction times, and careful exfoliation to prevent destruction. This method may be one of the most promising for large-scale fabrication of true monolayer materials.22, 52, 54–57

2.4 Potential for occupational exposure

The nature of the synthesis and processing methods govern the nature of potential occupational exposures. Based on experience with other nanomaterials, a useful distinction can be made between: (a) dry processes (vapor phase growth, dry exfoliation), and (b) wet processes (liquid-phase growth or liquid-phase mechanical or electrochemical exfoliation). Inhalation exposure is a primary concern and occurs most often during dry processing, when CVD reactors are opened, or dry powders are transferred or packaged. Vapor-phase processes that yield substrate-bound films are of less concern than those yielding free powders as primary products. Wet synthesis methods are preferred for managing airborne exposure, but wet growth is often followed by drying to produce powdered products, for which the same issues apply. Exposure issues in wet processing can also arise from spills and splashes, or for spray processing or aerosolization.58

There are limited data on airborne concentrations of 2D materials and their respirability, with most of the data on graphene19, 59 or from human health impact studies of sheet-like silicates (see Section 3). Graphene materials may reach the deep lung despite their large lateral dimension, and the atomic-scale third dimension greatly reduces their aerodynamic diameter and settling behavior.19, 59 Nanomaterial aerosols are often aggregates, and 2D materials form fundamentally different aggregate structures than 1D materials – they can stack face-to-face into robust, high-density aggregates rather than entangle into low-density spherical aggregates like carbon nanotubes.60 Research is clearly needed to measure airborne concentrations and identify aggregate structures when emerging 2D materials are subjected to common processing methods. Research is also needed on the respirability of 2D materials and their common aggregate and agglomerate structures.

An underappreciated aspect of 2D material safety is the chemical hazards associated with precursors or byproducts. For both liquid- and vapor-phase processes, toxic gases such as H2S, H2Te, and H2Se can be used as starting materials or are formed by decomposition during processing or with exposure to water.61–63 Most vapor phase reactions are carried out in sealed air-free environments, but during high temperature process failure some chalcogenides such as Bi2Te3 can react violently if exposed to moisture at high temperature. More information is also needed on the byproducts of 2D material synthesis, which must be managed as potential environmental pollutants, as has been pointed out for carbon nanotubes, whose growth intermediates include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.64

3. Literature review on biological response and risk

This section reviews in vitro, in vivo and epidemiological studies relevant to 2D material biological response and risk. In some cases where there are no specific data yet on the 2D monolayer or few-layer forms, we include data on bulk layered materials to provide information on intrinsic chemical toxicity, with the caveat that bulk behavior will not always be a reliable indicator of nanosheet behavior. Because neither in vitro studies nor in vivo studies in animal models are fully predictive of human disease, we include discussion of known health impacts in workers, and do this for what is arguably the best available case study today – exposure to sheet-like silicates. We begin with general information on material behavior organized by chemical class.

3.1 General information by chemical class

Selenides and tellurides

The largest class of 2D and layered materials is the chalcogenides (compounds containing S, Se, Te, or Po). Se and Te have various oxidation states from −2 to +6 in even numbers, and appear in several layered material states (Fig. 1). Upon dissolution or decomposition, these materials can release free Se or Te species (see Section 4.1), which are known toxicants for humans and environmental organisms. Selenium is an essential trace element in living organisms that include archaea, algae, bacteria, and many eukaryotes, but at higher doses is an established toxicant. Selenium has been implicated in livestock poisoning through a condition incorrectly referred to as “chronic alkali disease”,65 because it was wrongly attributed to alkaline salts in the soil.66 Chronic selenium poisoning causes hair loss in the manes and tails of horses, sore hooves in cattle, and poor egg hatchability in fowl.65 Very high levels of selenium cause blind-stupor and ultimately death in cattle. This condition is common in the several states of the US (Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska), where plants can contain up to several thousand ppm of selenium. Tellurium is chemically similar to selenium though more electropositive, more basic, and more metallic. It was noticed that acute tellurium exposure67 causes suppression of saliva and sweat in humans by paralyzing secretory nerves, similar to atropine. This is usually associated with dryness of the mouth and a metallic taste. Te also causes dilation of capillaries of splanchnic nerves in humans, similar to arsenic. Exposure, in small doses, also leads to somnolence (sleepiness).67 Tellurium is known to pass the blood-brain barrier and can accumulate in nerve cells.68 Rabbits injected with tellurium developed dark grey discoloration of the brain after prolonged administration.68 Injection of tellurium in rats, led to hydrocephalus in their offspring.

In acute selenium or tellurium poisoning, whether through exposure to solid materials or through vapor inhalation, organoselenium species are released as dimethyl selenide, dimethyldiselenide, dimethyl telluride, or dimethylditelluride. This results in a characteristic garlic odor.65, 69 Microorganisms make methyl-selenide, dimethyl-selenide, dimethyl-diselenide and dimethyl-selenenyl-sulfide with selenium exposure. In some microorganisms this leads to the formation of selenium (0) which can likely bioaccumulate.69 Exposure to Se and Te can lead to replacement of sulfur in peptides and proteins.70 Organoselenium and organotellurium byproduct compounds can react with thiol groups from biologically important molecules and oxidize them to disulfides.71 During synthesis or processing of Se- or Te-based 2D materials, exposure to water or atmospheric moisture can generate H2Se or H2Te gases, which have a characteristic odor and are highly toxic.

Sulfides

Sulfur is an earth abundant element that is also common in biological systems and not usually associated with toxic effects. For this reason, any health concerns associated with sulfides are likely governed by the metal constituent, or a unique solid-state behavior of the sheet-like compound (Section 4.2). Molybdenum sulfide, MoS2 is currently the most intensely investigated of the 2D materials beyond graphene. It has received enormous attention for the appearance of an indirect to direct band gap transition as it is exfoliated to a monolayer.4 MoS2 also has several superior catalytic properties for hydrogen evolution and hydrodesulfurization – both properties that are affected by the number of layers of the material.13 Bulk MoS2 has been an industrial material for over a century, serving as a solid lubricant. As a mineral, molybdenite, it is a major byproduct of mining and is also major mineral constituent of acid mine drainage.72, 73 Metal sulfides are formed in geological environments such as a sulfur-heavy, reducing atmosphere. After the process of mining, these metal sulfides often as wastes and including MoS2, are exposed to water, bacteria, and atmospheric oxygen. Slowly, these materials begin to oxidize and in the process generate acidity, for example in the form of sulfur acid.73 Bacterial activity enhances dissolution of sulfide metals and subsequent creation of heavy metals. This toxic mixture can lead to contamination of groundwater, rivers, and environmental ecosystems. Although most forms of sulfur are not toxic, sulfide-based 2D materials can evolve the toxic gas H2S during processing, an example being the exposure of the layered phases smithite (Fe3S4) or mackinawite (FeS) to mild acids.74

Oxides

Only a few of the 2D materials in Figure 1 are oxides, and some of these have polymorphs that are not simply layered. As an example, lead oxide has two polymorphs; of these only the tetragonal α-PbO (litharge, yellow lead) is a layered material. Many transition metal oxides are reactive and potentially toxic in nanoparticle form, as they exhibit increasing catalytic activity and dissolution rates at small sizes. Micron-sized vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) is a layered material with notable toxicity, landing it on the EPA “p-list” of acutely hazardous chemicals. It exhibits unique chromic properties and has been investigated as a lithium ion battery electrode material.13 Bulk V2O5 is also used as a catalyst in industry – for example in the manufacture of sulfuric acid and steel alloys, and is a byproduct of petroleum processing.75 Emissions of V2O5 from natural sources such as volcanoes, sea salt spray, forest fires, and other biogenic processes has been estimated at 8.4 metric tons annually.76–78 As a layered material, bulk V2O5 has been the subject of numerous biological response studies. It is genotoxic,79 and causes destruction of the testicular and liver architecture in male guinea pigs, and has been reported to be a developmental toxicant in mice.80 To our knowledge, there is no specific data on the 2D (exfoliated) forms of V2O5.

Molybdenum trioxide, MoO3, exhibits similar chromic properties to V2O5, changing color from transparent white to blue upon intercalation in the bulk form.13 It is important in the 2D field, standing out as the layered precursor for many MoS2 growth methods.26 Bulk molybdenum oxide itself is an industrial byproduct from the metal alloy industry, and is used as a catalyst and a pigment. Ingested as a solid, bulk MoO3 powders are fatal to rats and guinea pigs at 1200 to 6000 mg, which is a high dose, while inhalation of its vapor does not lead to fatality,81 Nanoscale MoO3 also exhibits anti-bacterial and anti-fouling properties,82 which suggests its future use in marine paints or coatings.

Oxyhalides

Oxychloride materials have received little attention in the 2D field though several synthetic routes exist to create nanosheet forms.83, 84 Layered bismuth oxychloride is used in some cosmetics for its appearance, where it is referred to as “synthetic pearl”. Before the arrival of antibiotics, it was used to treat syphilis.85 No carcinogenicity is observed following ingestion of large quantities of bulk bismuth oxychloride by rats.86 Another common layered oxychloride is AlOCl, which is now used commercially as in antiperspirant formulations.

Metal toxicity

Most of the 2D materials in Figure 1 contain metallic elements, which upon dissolution or degradation (Section 4.1) can induce biological responses characteristic of the element and its soluble species. Because of the diverse sources of metal contamination in the environment, many of these effects have been well characterized and the subject of extensive reviews on metal toxicity.87–92 Metals or metalloids found in 2D materials include well-known toxicants such as Hg, Pb, and As with their own extensive literature on environmental and human health effects. Among the most common metals found in emerging 2D materials are molybdenum, tungsten, manganese, vanadium, bismuth, and nickel. Molybdenum is an essential trace element for both animals and plants, and in mammals is incorporated in certain metalloflavoproteins.93 Molybdate is also an antioxidant and has been tested for treatment of diabetes in animal models.94 In plants, it is necessary for fixing of atmospheric nitrogen by bacteria at the start of protein synthesis. Molybdenum ions have relatively low toxicity, but mobilization and extracellular release of cadmium, nickel, and chromium ions are of concern because they are lung carcinogens.95, 96 Vanadium compounds are cofactors for several enzymes, although vanadium salts can inhibit phosphatases, protein kinases, and ribonucleases.97 On the other hand, vanadium salts are important for iron, thyroid, and cholesterol metabolism and have been proposed for treatment of diabetes and cancer.98 Similar to vanadate, sodium tungstate has been shown to be effective in animal models of diabetes.99 However, soluble sodium tungstate administered chronically to rats has been shown to induce oxidative stress in the brain and neurobehavioral changes.100, 101 Heavy metal tungsten alloy particles are used as a less toxic alternative for depleted uranium for military applications. However, these particles have been shown to induce acute oxidative stress and lung toxicity following intratracheal instillation in rats.102 Tungsten carbide cobalt (WC-Co) particles are known to induce hard metal lung disease associated with fibrosis or scarring and lung cancer following occupational exposure.103 In an in vitro model using human lung epithelial cells, nano-WC-Co particles were more toxic than micro-WC-Co particles.104 Implantation of heavy metal tungsten alloy pellets into rat muscles produced aggressive tumors at the implantation site.105 Manganese is an essential element important for brain glutamate metabolism, energy metabolism, immune function, and growth of bone and connective tissues.90, 91 Mn+3 is more toxic than Mn+2 or Mn+4 and is redox active.92 High levels of manganese accumulate in the brain following inhalation by humans associated with a Parkinson-like disease.106 Metallic bismuth is used as a lead substitute and there is concern about potential toxicity following occupational exposure. In comparison to lead, repeated oral doses in rats produced minimal toxicity up to 1,000 mg/kg.107 Bismuth salts and colloidal compounds have been widely used in humans for treatment of skin lesions, syphilis, and gastrointestinal disorders. Due to limited absorption and low solubility, these compounds have low toxicity when tested using in vitro cellular toxicity assays at doses up to 100 µM.108 Bismuth has a low toxicity for a heavy metal, but is known to bioaccumulate in algae.109

3.2 In vitro and in vivo studies

Table 1 summarizes the current literature on the biological response to 2D materials, including oxides, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), and metal chalcogenides. Bulk MoS2 materials are generally regarded to have low toxicity,110 and only recently have studies begun to address the 2D forms. Teo et al.111 compared the toxicity of exfoliated versions of transition metal dichalcogenides with three different chemical compositions: MoS2, WS2 and WSe2. The studies using lung epithelial cells (A549) concluded that all three materials showed low cytotoxicity up to 100 µg/ml, and that WSe2 nanosheets alone began to show toxicity above 200 µg/ml. Since WS2 and WSe2 nanosheets both contain tungsten, the data suggest that the adverse effects of WSe2 nanosheets at high dose are related to the specific chalcogen: Se. Chng et al.112 pursued a different question by studying a single chemistry (MoS2) but using a variety of preparation methods to compare MoS2 materials with different degrees of exfoliation (thickness/layer-number). Similar to Teo et al., they report low toxicity in all versions of 2D exfoliated MoS2, but do see cytotoxicity at high doses (above about 100 µg/ml) and the most cytotoxic materials are those with higher degrees of exfoliation (fewest layers). The cytotoxicity trends may reflect a fundamental effect of thickness (e.g. membrane damage caused by atomically thin edges in the most exfoliated samples) or elevated surface area.112 The discussion in Section 4.1 suggests such area effects in MoS2 may be related to increased rates of oxidative dissolution leading to increased concentrations of free molybdenum species. Wang et al.110 also report low cytotoxicity for several different formulations of MoS2 nanosheets, but go on to show that aggregating the nanosheets by flocculation increases pro-inflammatory responses both in vitro and in the mouse lung. This study suggests that “2D–MoS2 nanomaterials are relatively safe” and that their safety is promoted in formulations that ensure good dispersion. Shah et al.113 also report no loss of viability in cells exposed to few-layer MoS2 nanosheets at doses up to 100 µg/ml. All of these studies use MoS2 nanosheets of small lateral dimension (< 1 µm and typically < 200 nm), so the important issue of size effects, and the increased biological response to materials with large lateral dimension as reported for graphene-based materials,19, 20, 114, 115 remains unexplored for these other 2D materials (see section 4.2).

Table 1.

Toxicity of 2D Materials and their Compound Materials

| Materials | Exposure Method | Species/Cell Types | Biological Outcomes | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D and 2D Layered Materials | ||||

| MnO2 | cell culture | Human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) | ~45 % viability after exposure to 100 ppm PEG coated nanoplates (width 20–70 nm) for 24 h | 128 |

| MoO3 | cell culture | Human breast cancer cells (iMCF-7 and MCF-7) | ~ 40–50 % viability after 48 hr exposure to 400 ppm as-prepared nanoplates (400 nm × 100–200 nm) | 127 |

| TiO2 | IP injection | mice (C57) | PEG coated TiO2 nanosheets (anatase, lateral dimension 92.5 nm) accumulate in liver and spleen and cause appreciable toxicity in liver at 10 µg/g-body weight. |

126 |

| WS2 | cell culture | mouse mammary gland cancer cells (4T1), Human Cervix cancer cells (Hela), human kidney cancer cells (293T) and human lung cancer cells (A549) |

~ 50% viability for 4T1, Hela, 293T after 24 hr exposure to 100 ppm nanosheets; ~30% viability for A549 after 24 hr exposure to 400 ppm nanosheets (lat. dim. ~500 nm, thickness ~20 nm) |

129,111 |

| MoS2 | cell culture; oropharyngeal aspiration |

human Cervix cancer cells (Hela) and human lung cancer cells (A549); Escherichia coli (E. coli) K12; human leukemia monocytes (THP1) and human lung cells (BEAS-2B) and C57Bl/6 mice; rat kidney cells (RAMEC) and rat Adrenal Gland cells (PC-12) |

~70–95% viability for Hela cells exposed to 160 ppm PEGylated nanosheets (50nm × 2nm); ~50% viability for A549 cells exposed to 400 ppm nanosheets (~400x~4.5 nm); cell viability decreases as extent of exfoliation increases in panel of MoS2 nanosheets; Aggregated but not dispersed MoS2 nanosheets induce acute lung inflammation in mice; no loss of viability in RAMEC and PC 12 cells exposed to few-layer MoS2 nanosheets at doses up to 100 µg/ml. |

110–113, 119, 123 |

| WSe2 | cell culture media | human lung cancer cells (A549) | ~30 % viability for A549 after exposure to 400 ppm as-exfoliated materials (lateral dimension ~200 nm, thickness ~7 nm) for 24 hrs |

111 |

| Bi2Se3 | cell culture media; IP injection |

mouse liver cancer cells (H22); male mice (C57) | ~90 % viability for hepatocarcinoma H22 cells after exposure to 200 ppm PVP-coated nanosheets (rhombohedral phase, lateral dimension 90 nm, outer layer 3.6 nm, inner thickness 21 nm) for 24, 48, 72 h; IP injection of PVP- coated Bi2Se3 nanosheets (50 nm × 6 nm) in mice at doses up to 20 mg/kg produced no obvious adverse effects on growth or changes in body weight up to 90 days, and a panel of measurements focused on immune response, hematology, and biochemistry suggested “limited biological damage” |

125, 130 |

| TiS2 | cell culture media and intravenous injection |

mouse mammary gland cancer cells (4T1); mice (Balb/c) |

No obvious toxicity with up to 100 pm TiS2-PEG nanosheets (cubic phase, lateral dimension ~100 nm) to 4T1 cells and no obvious damage to mouse organs up to the 2 mg/mL, 200 µl TiS2-PEG injection (20 µg/g-body weight) |

124 |

| Other Nanomaterials Forms (Particulate or Fibrous) | ||||

| MnOx | Inhalation; cell culture |

rats (Fischer 344); rat liver fibroblasts (BRL 3A) |

Manganese oxide nanoparticles (30 nm) altered gene expression in olfactory bulb, frontal context, midbrain, striatum, cerebellum rats after 11 days of inhalation; 60% viability for BRL 3A cells exposed to 250 ppm particles for 24 h. |

131,132 |

| h-BN | cell culture | human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293); rat adrenal gland cells (PC-12) |

Nontoxic up to 100 ppm for HEK293 cells after exposure to h-BN multiwalled nanotubes (diameter 20–30 nm, length up to 10 mm) for 4 days; 20% decrement of metabolic activity for PC12 cells after exposure to 100 ppm bamboo-like nanotubes (diameter 50 nm, length 200–600 nm) for 9 days. |

133, 134 |

| MoS2 | cell culture | human lung cancer cells (A549), human bone marrow leukemia cells (K562), human embryonic skin fibroblasts (CCC-ESF-1) |

No cytotoxicity for A549, K562, CCC-ESF-1 cells after exposure to 3.5 ppm nanoparticles (hexagonal phase, 120 nm) for 48 h |

135 |

| MoO3 | cell culture | rat fibroblasts (BRL 3A); human bone osteosarcoma cells (U2OS ) |

~ 60 or 50 % layered double hydroxide (LDH) leakage and ~20 or ~40 % viability for BRL 3A cells after exposure to 250 ppm nanoparticles (30 or 150 nm) for 24 h; No cytotoxicity for U2OS cells after exposure to 4 ppm nanospheres (290.4 ± 66.7 nm) for 2 h; |

132, 136 |

Antimicrobial activity of 2D graphene oxide nanomaterials and nanocomposites has been linked to their shape, dimensions, chemical composition, and surface properties.116 There is very limited information on the antibacterial activity of other emerging 2D nanomaterials. The geometry of nanomaterials has been reported to alter phototoxicity and bacterial killing by nano-TiO2 with nanosheets and nanotubes exhibiting lower phototoxicity than nanorods or nanospheres. However, alignment of nanosheets at the bacterial surface also impacted toxicity117 similar to graphene oxide sheets of large lateral dimension.118 A study performed by Fan et al.119 focused on environmental applications using 2D MoS2 to evaluate antibacterial activity. In this work the antimicrobial performance of exfoliated 2D MoS2 versus annealed 2D MoS2 in combination with EDTA was examined. This study revealed that the restacked exfoliated MoS2, which differs in phase composition from the exfoliated MoS2, leads to a significantly greater inactivation of Escherichia coli biofilm production then the annealed MoS2. Higher electron conductivity of 2D MoS2 leads to increased generation of reactive oxygen species and toxicity to both planktonic bacteria and mature biofilms without causing significant toxicity in eukaryotic cells. In this regard exfoliated MoS2 in combination with EDTA has similar potential as graphene oxide composites for water treatment applications and inhibition of biofilm formation as described previously.120 Krishnamoorthy et al.121 showed that MoO3 platelets cause toxicity in 4 different bacteria strains, due to physical disruption of bacterial cell walls with potential application as an antibacterial agent.

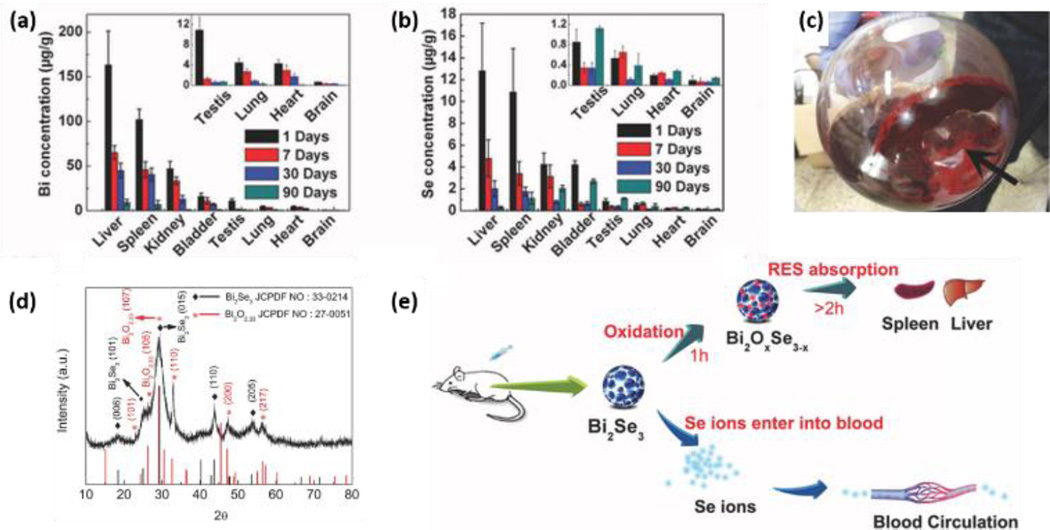

Studies on biomedical applications often contain some relevant information on toxicity/biocompatibility. Kou et al.122 report low cytotoxicity for 2D MoS2, coated with PEG/PEI as a carrier for gene delivery. Liu et al.123 showed that MoS2 and MoS2-PEG nanosheets do not cause significant toxicity in HeLa cells at concentrations up to 0.16 mg/ml for 24 hrs, and that plain MoS2 causes only a slightly increased toxicity at day 2 and 3 (around 80% and 73% viability) versus 90% viability in MoS2-PEG nanosheet-exposed HeLa cells at this concentration. PEGylated TiS2 nanosheets are reported to have low cytotoxicity in a murine breast cancer cell line up to a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml for 24 hrs.124 Zhang et al.125 explored polymer-coated Bi2Se3 nanosheets (50 nm × 6 nm) as tumor inhibitors and contrast agents due to the high atomic number of Bi (see Fig. 4). Direct injection in mice at doses up to 20 mg/kg produced no obvious adverse effects on growth or changes in body weight up to 90 days, and a panel of measurements focused on immune response, hematology, and biochemistry suggested “limited biological damage”.125 This study focused on biokinetics and showed clearance of the elemental Bi and Se over time scales from 2 – 90 days, and also reported the instability of Bi2Se3 nanosheets to oxidation as a dry powder in air or in cell culture medium (see Section 4.1).

Figure 4.

In vivo clearance of elemental Bi and Se and oxidation/dissolution of Bi2Se3 nanosheets. Time-depnedent decrease of Bi concentratoin (a) and Se concentration (b) caused by clearance effects. Digital image (c) and XRD spectrum of the oxidized Bi2Se3 nanosheets after exposure to air for 30 days (d). (e) Illustration showing dissolution and oxidation of the Bi2Se3 nanosheets after intraperitoneal injection. Reprinted with permission from ref. 125. Copyright 2013, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Song et al.126 report low toxicity for TiO2 nanosheets following intraperitoneal injection into mice, but also report particle accumulation in the liver, leading to minor abnormalities after prolonged exposure times. Tran et al.127 report that MoO3 nanosheets induce toxicity in the breast cancer cell line MCF7 by activation of the caspase pathway, but not in keratinocytes (HaCAT cells), suggesting possible applications in the treatment of breast cancer. MoO3 platelets have also been reported to be toxic to bacteria.82 In an exploration of MnO2 nanoplates as MRI contrast agents, a significant decrease of cell viability was reported in the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 suggesting that doses will need to be limited to avoid cell damage.128

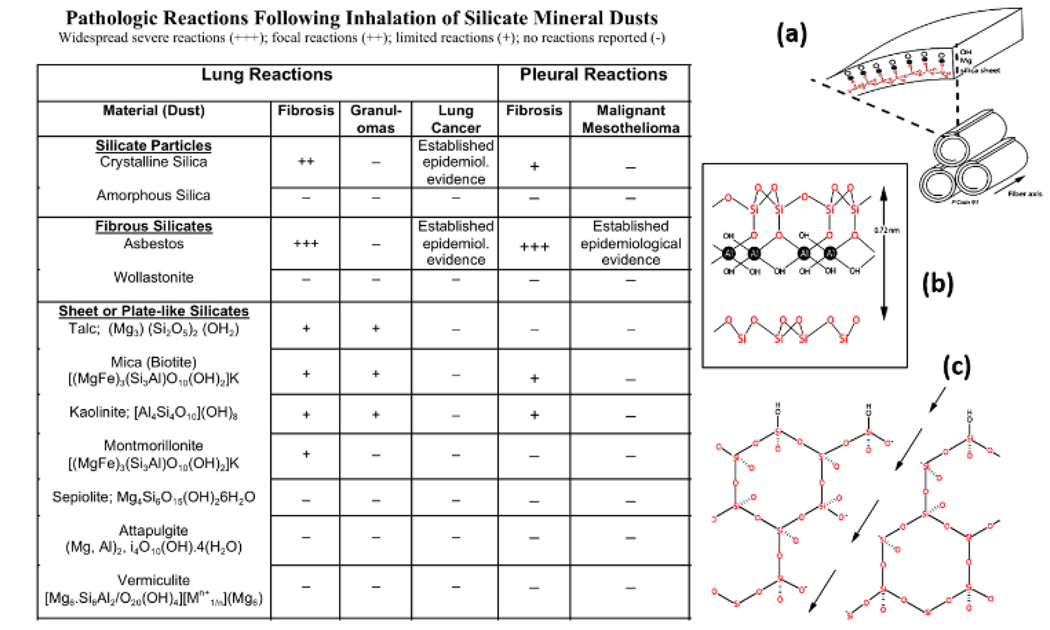

3.3 Human health impacts of 2D materials – a case study on sheet-like silicates

The largest body of data on human health effects associated with exposure to sheet-like materials comes from decades of experience in the mining, manufacturing, and applications of naturally occurring sheet-like silicates. Reviewing this literature may help us anticipate the issues that may arise with occupational exposure to the broader set of emerging 2D synthetic materials. The most important class of natural 2D silicate minerals are clays, which are composed of tetrahedral and octahedral sheets based on SiO4 tetrahedra as the basic unit. Kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4) for example, is a 1:1 layer silicate with a sheet of SiO4 tetrahedra bonded to an octahedral sheet of Al(OH)6 (Fig. 5b). Tetrahedral sheets bonded to an octahedral sheet on both sides are 2:1 layer silicates. The covalently bonded layers are separated by a hydrated gap that contains cations such as K+ in mica and Mg2+ or Ca2+ in vermiculite.137 The octahedral and tetrahedral sheets are called platelets, each approximately 0.1 – 0.5 µm in lateral dimension and 1 nm thick usually stacked in multiple layers,138 and in this regard have very similar dimensions to the emerging 2D synthetic materials. Clays are frequently used as composites in the building industry, in agriculture and in manufacturing of paper, plastics and ceramics.

Figure 5.

Structure and human health effects of sheet-like silicate minerals. Table 2 summarizes the known pathological responses to inhalation as a function of material type. (a) Crystal structure of chrysotile asbestos.139 Reprinted with permission from ref. 139. Copyright 2004, Springer. (b) Crystal structure of kaolinite, which is a 2D silicate clay mineral. (c) Lattice of crystalline silica or α-quartz. Fracturing the crystal along the arrows generates highly reactive Si• or SiO• dangling bonds on the new surface.140 Reprinted with permission from ref. 140. Copyright 1996, Taylor & Francis.

Bulk unprocessed sheet silicates (e.g. vermiculite) may be 100–1000 µm in lateral dimension,141 and can be delaminated producing nanoplates ~ 0.2 – 10 µm in lateral dimension and 10–40 nm thick142 using chemical exfoliation, sonication, or thermal shock.141 Chemical exfoliation of vermiculite into single silicate crystals was reported by Walker and Garrett using ion intercalation to produce swollen crystals that can be disrupted by shearing.137 These single silicate monolayers can be deposited on a flat surface and stripped off as very strong, flexible films; however, these 2D sheets have not been exploited commercially.

Similar to emerging 2D materials, some sheet-like silicates can roll up into fibrils to create 1D structures, and some of these pose serious human health concerns. Chrysotile asbestos is a 1:1 layer silicate that is rolled up in a spiral to form fibrils (Fig. 5a). These fibrils aggregate into bundles or fibers ~ 25 nm in diameter and up to 40 µm long143 that are highly flexible, long, and thin. Chrysotile asbestos fibers are very strong, chemically inert, heat resistant, and non-conducting and are widely used in roofing, insulation, tiles, wall board, and reinforcement for concrete.144

In contrast to these sheet-like and fibrous silicates, pure SiO2 is an abundant mineral that occurs as crystalline silica or α-quartz or as amorphous silica.145 Crystalline silica is used in concrete, mortar, porcelain, paints, and abrasives.145 Amorphous silica lacks the fixed geometric spatial orientation of crystalline silica. Synthetic amorphous silica is produced as a gel, thermal or fumed silica, or chemically modified, precipitated silica and used as fillers in the rubber industry, carriers in agrochemicals, paints, adhesives, inks, and cosmetics.146

Pneumoconiosis is a general term used to describe reactions of the lungs to dust inhalation that range in severity (Table 2) depending on the composition of the dust, dose, and duration of exposure.147 Mining, milling and processing of spherical and fibrous silicate minerals is a well-recognized occupational hazard. Crystalline silica or α-quartz represents 12 wt % of the earth’s surface. Rocks containing crystalline silica may have associated impurities, most commonly Al, Fe, and Ti. Inhalation of some sheet silicates has been associated with pneumoconiosis; however, naturally-occurring silicates are frequently contaminated with crystalline silica or asbestos fibers. The lung reactions to these mixtures have been named “mixed-dust pneumoconiosis” and occur in workers exposed to talc contaminated with crystalline silica or asbestos fibers148 and to mica or kaolinite contaminated with crystalline silica.149 Case reports of workers exposed to prolonged high levels (≥ 5 mg/m3) of pure talc, mica, or kaolinite who develop silicate pneumoconiosis have been published.148, 150 Other sheet silicates such as vermiculite are not associated with pneumoconiosis; however, a vermiculite mine in Libby, Montana is contaminated with asbestos fibers that are responsible for asbestosis or fibrosis of the lungs, fibrotic pleural plaques, lung cancer, and malignant mesothelioma in the vermiculite miners and residents.151, 152 Asbestos fibers are not readily cleared following inhalation and cause severe diseases of the lungs and pleural linings surrounding the lungs in contrast to wollastonite, a highly soluble fibrous silicate that is not associated with lung or pleural disease (Table 2). Inhalation of crystalline silica particles, but not amorphous silica, is also associated with development of lung fibrosis and cancer (Table 2);146 amorphous silica has a high surface area and dissolves more rapidly than crystalline silica, which is very biopersistent.153 The crystal lattice of α-quartz is a network of tetrahedral SiO2 units (Fig. 5c). Crushing or mining of crystalline silica fractures the crystal into small fragments in the micron size range which are respirable and have highly reactive dangling bonds at the surface.140

Sheet silicates may pose a potential health risk to workers because these exfoliated sheets can be less than 5 µm in aerodynamic diameter and are thus respirable, similar to other 2D materials such as graphene.115 Consumers and end users of commercial products containing sheet silicates typically have low levels of exposure and no significant health risks. Minimal toxicity has been shown following oral or dermal exposures in experimental animals.154 Humans have also been exposed to clay minerals used for food packaging and as pharmaceuticals with no reported toxicity.138 Clays have been added to the diet to adsorb aflatoxin, a highly toxic and carcinogenic food contaminant.155 Deliberate ingestion of soils containing clay is called geophagia and may cause nutrient deficiency due to adsorption by clay minerals.156 Clay minerals and composites are used for medical applications for sustained release in drug delivery, in hydrogels, and in periodontal films;157 no parenteral toxicity has been shown in experimental animals.154 However, repeated intravenous injections of drugs containing talc can cause serious inflammation and scarring in the lungs.158

Particle toxicity is related to chemical and physical properties of the mineral as well as shape and dimensions that influence lung deposition, clearance, and translocation.153, 159, 160 In general, particles up to 10µm in diameter can deposit in the alveolar spaces while smaller nanoparticles can penetrate into the lung interstitium and lymphatics and disseminate to distant sites. Macrophages are the primary cellular target of inhaled particles deposited in the conducting airways or alveolar spaces following inhalation. Engulfed particles accumulate in cytoplasmic membrane-bound vesicles called lysosomes where they are degraded by hydrolytic enzymes or stored.161, 162 Crystalline silica, sheet-liked silicates, and amphibole asbestos fibers are not biodegradable and persist in the lungs, in contrast to amorphous silica or wollastonite fibers that are more soluble and induce only transient inflammation (Table 2). In contrast, chrysotile asbestos is a serpentine silica mineral and the outer layer is brucite – Mg(OH)2, Figure 5a. Under acidic conditions in the lysosomes of macrophages, the outer brucite layer is leached allowing the fibers to split transversely into shorter fibrils that are cleared from the lungs.153, 163 In general, biopersistent minerals are more likely to induce chronic lung inflammation and fibrosis or scarring. Long, rigid fibrous minerals or large sheet-like silicates are incompletely phagocytized by macrophages 159 and induce formation of aggregates of inflammatory cells or granulomas and fibrosis (Table 2).

Highly toxic mineral particles can damage cellular and lysosomal membranes causing release of mediators that trigger inflammation or cell death.159, 164 Particle surface properties and surface reactivity, not bulk physical structure or chemical composition, are hypothesized to cause membrane damage in target cells.153, 165 The surface properties of crystalline silica resulting in lysis of red blood cell membranes (hemolysis) and lysosomal membrane disruption of macrophages are well known. Freshly-fractured crystalline silica exposes Si• and Si-O• dangling bonds on the cleavage planes that react with water to form highly toxic hydroxyl radicals (Fig. 5c)153, 163 that cause severe acute lung injury in silica miners. Depending on the geographic source and surface contaminants or impurities, aged crystalline silica is also toxic due to two surface chemical functionalities: silanols or –SiOH groups that form H bonds at neutral pH resulting in membrane disruption and dissociated silanols or siloxane – SiO− groups that are negatively-charged. This negative surface charge can be masked by Al3+, Zn2+, or Fe3+ ions, and aluminum-containing clays have been shown to reduce the toxicity of α-quartz.163 In recent comparative studies of a panel of well-characterized bulk and nanoscale silica samples, Pavan et al.166, 167 demonstrated that a defined spatial distribution of silanol and siloxane groups at the particle surface interacts with red blood cell and lysosomal membranes to disrupt their structural integrity resulting in hemolysis or lysosomal membrane destabilization.

In contrast to the well-described mechanisms for membrane reactivity of crystalline silica, the mechanism responsible for induction of hemolysis by sheet like silicates is unclear. Silicates like kaolinite have a net negative surface charge, but also have other functional groups with a positive charge resulting in overall amphoteric properties, depending on pH. Both silica and sheet-like silicate minerals adsorb phospholipids in cell membranes and in surfactant lung lining fluid. Keane and Wallace164 propose that phospholipid adsorption in the lung lining fluid is initially protective, but that the phospholipid coating is gradually digested in macrophage lysosomes. Differential lung toxicity of crystalline silica and sheet-like silicates may be related to slower rates of lysosomal degradation of adsorbed surfactant lipids. Alternatively, similar to 2D graphene nanosheets of large lateral dimension, sheet-like silicates may be less readily engulfed by macrophages than spherical crystalline silica particles19 resulting in less extensive lysosomal membrane disruption and lower release of inflammatory mediators. In the case of sheet-like silicate minerals, in vitro hemolytic activity is not predictive of in vivo toxicity and pathogenicity.

3.4 Implication for potential adverse health impacts of emerging 2D nanomaterials

Lessons can be drawn from these historical studies of toxicity of crystalline mineral particles and one-dimensional fibers. First, toxicity depends on surface chemical and mechanical properties, as well as material dimension and shape, and factors like aging and chemical and thermal treatments are important because they influence surface reactivity.153, 165 Surface chemistry and reactivity have shown to be important for toxicity of amphibole asbestos fibers due to iron-catalyzed generation of reactive oxygen species at the fiber surface.163 Endogenous biological chelators can mobilize this surface iron enhancing generation of reactive oxygen species in cells and in vivo; conversely, deposition of iron and protein onto fiber surfaces may either mask or enhance surface reactivity.153 Secondly, in vitro assays may not be predictive of in vivo biological activity if they do not consider in vivo surface modifications such as protein and lipid adsorption and subsequent target cell-particle interactions that may lead to additional surface modifications or particle leaching and degradation. Thirdly, we can expect material stability or biopersistence to be an important variable. Long, rigid one-dimensional fibrous particles that are resistant to dissolution can remain in the lungs or translocate to the pleura where they induce both lung and pleural fibrosis and cancer.168, 169 One-dimensional fibrous or high-aspect ratio nanomaterials are incompletely phagocytized by macrophages and induce lysosomal membrane permeabilization resulting in release of inflammatory mediators and secondary generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by inflammatory cells.159, 170 Crystalline silica particles are also highly biopersistent and induce persistent inflammation and reactive species generation that may lead to development of lung cancer.171, 172

Finally, the ability of the lung to clear foreign objects is likely to be important, and clearance of 2D materials may be impaired for flakes of large lateral dimension or for large aggregates, as has been shown recently for graphene-based materials.59, 173, 174 In early data on emerging 2D materials, exfoliated and well-dispersed MoS2 nanosheets were shown to induce less inflammation than aggregated MoS2.110 It is clear that during these early stages in synthesis, fabrication, and application of these novel 2D nanomaterials and their composites, occupational and environmental exposures must be controlled and carefully monitored to protect the health of workers, end-users, and consumers.

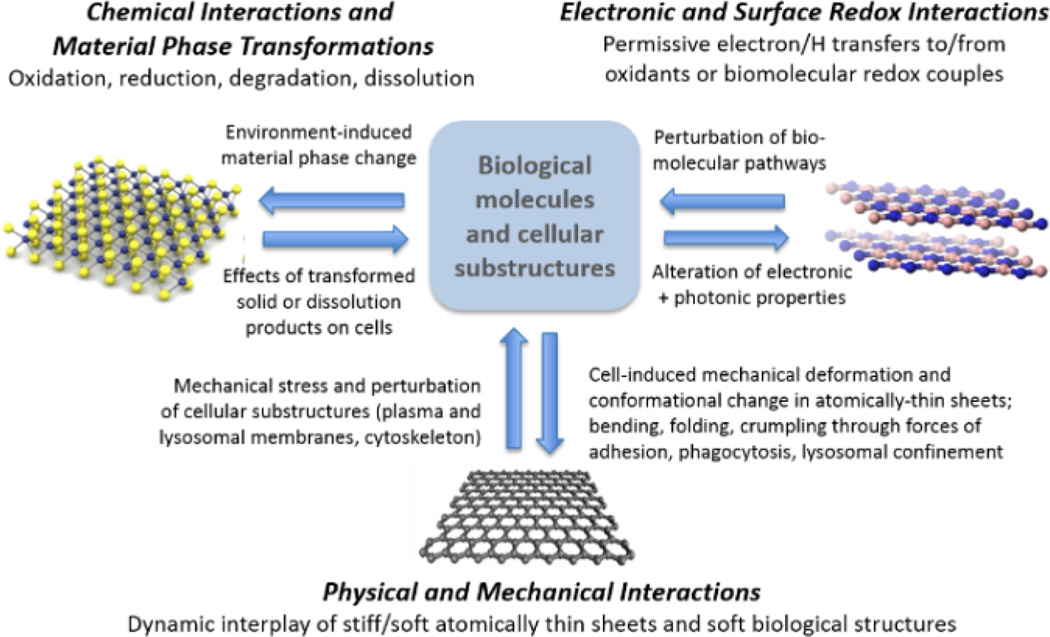

4. Fundamental modes of biological interaction

As discussed in Section 1, the extreme diversity in the 2D material family (Fig. 1) presents challenges to any approach that requires in vivo testing of each specific material of interest for risk assessment. There is strong motivation to address the problem more systematically through generalized methods or frameworks that group materials into rational classes, and for screening of materials to prioritize them for more detailed examination as part of a tiered testing strategy (e.g. see the work by Oberdörster et al.175) The central premise in this section is that the biological responses to 2D nanomaterials are initiated by material-specific behaviors that can be understood through fundamental materials chemistry and physics. More than a decade of nanotoxicology research focused on particulate and fibrous nanomaterials has provided significant insight into the fundamental chemical and physical basis of these behaviors. Here we propose a framework in which the interactions of 2D materials with biological systems are classified into three basic modes: chemical, mechanical, and electronic (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Fundamental modes of interaction between 2D materials and biological systems. The arrows show the bidirectionality of the interactions, in which the biological environment induces chemical or physical material transformations, while the materials and/or their transformation products induce biological responses.

Chemical interactions occur for materials in non-equilibrium states, which upon immersion in biological fluids undergo reaction or phase transformation that profoundly alters their structure and properties. Of particular importance are oxidative and reductive dissolution processes that release soluble ionic species that are often the primary drivers of adverse biological responses.

Physical and mechanical interactions between 2D materials and soft biological structures are governed by mechanical stiffness, surface charge and polarity. Mechanical interactions are of special importance for low-dimensional nanostructures (also known as high-aspect-ratio nanomaterials), which can mechanically perturb soft cellular substructures such as plasma and lysosomal membranes (Fig. 6). For example, long, stiff nanotubes have been implicated in adverse biological responses associated with frustrated cellular uptake and cytotoxicity.143 In 2D materials, atomically sharp edges can cause spontaneous penetration of cell membranes with low energy barriers and can lead to lipid extraction and membrane damage.114 Following cellular uptake, low-dimensional materials may cause mechanical stress, deformation, and damage when cells attempt to package large, stiff plate-like or fibrous structures into soft spherical lysosomes.

Finally, 2D nanomaterials can perturb biological process through electronic and surface redox interactions (Fig. 6). Permissive electron transfers or H-transfers between material surfaces and biomolecular redox couples in cells and tissue can perturb essential biochemical pathways or initiate new pathways that lead to adverse outcomes such as those mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. The remainder of Section 4 explores these fundamental interaction modes in more detail.

4.1 Chemical interactions and material phase transformations

Over a decade of nanotoxicology research has shown that nanomaterials typically interact with biological systems in chemically specific ways that reflect their unique elemental compositions, phases, and surface chemistries. Immersion of as-produced nanomaterials in biological environments often creates non-equilibrium systems that drive material phase transformations, including oxide formation,176 sulfidation,177 selenium/sulfur replacement,178 degradation, and dissolution driven by oxidation179 or hydrolysis.180 Chemical interactions between material surfaces and biological fluid phases also include chemical adsorption of ions, small molecules,181 proteins,182 and ligand exchange.181 Physical transformations such as aggregation, dispersion, settling, and deposition are also important,183–185 but are not the focus of this review. In some cases, transformations occur in the natural environment prior to exposure (Section 5), and the relevant biological response is not to the original material, but to its transformation products.186 Even during occupational exposures to freshly prepared materials, transformations can occur in the human body, which at different times interacts with the as-produced material, the final transformation product, and potentially reactive intermediate states that arise during the dynamic transformation process. A variety of phase transformations have been observed in 2D materials, examples including S replacement by Se,187 or alkali metal intercalation in TMDs, which converts the 2H phase to the metallic 1T phase.188 Most studies to date have not used physiologically-relevant fluid phases, so the relevance of the reports to biological interactions is unclear. Monolayer and few-layer materials have extraordinarily high surface areas, so biomolecular adsorption, including protein corona formation, is expected to be particularly important, but are also currently unexplored.

Among the possible transformations, dissolution is particularly significant for the biological response, since soluble dissolution products that co-exist with the solid phase have been implicated in the toxic responses for many nanomaterials, including Ag,178, 189 Cu,177, 190 ZnO,191, 192, CdSe,193 Ni and NiO.194, 195 The toxicological significance of material dissolution can be rationalized in general terms as a consequence of atomic bioavailability. A toxic metal in particle form interacts with biological molecules only at surface sites, which typically involve a very small fraction of the metal atoms (true in all but the smallest nanoclusters). In contrast, the same metal as free species in solution can be fully bioavailable at the atomic level with each ion or complex able to engage in chemically specific interactions such as thiol binding or redox cycling or metal substitution in enzymes or ion channels. Because dissolution is such a significant transformation, the following section examines dissolution chemistry in detail for 2D materials.

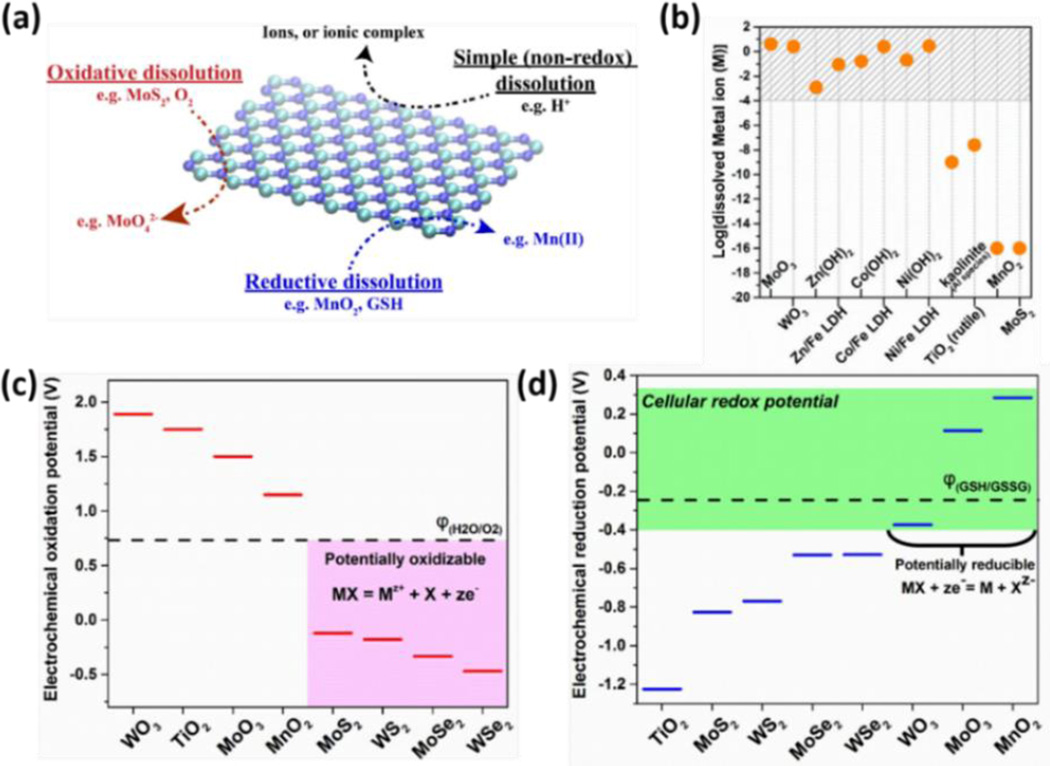

Dissolution processes for 2D materials

Biological dissolution is not a simple process -- it often involves solid-phase oxidation or reduction that occurs by rate-limiting chemical reactions with oxidizing or reducing agents in local fluid environments,196, 197 and the ion release can be promoted or inhibited by biomolecular ligands that complex ions in solution and reduce their chemical potential, or those that bind to and passivate particle surfaces.177, 196 We start here by considering three distinct dissolution modes: simple (non-redox), oxidative, and reductive (Fig. 7a), and review the existing literature on the basic chemistry of layered materials relevant to these complex processes.

Figure 7.

Dissolution behaviors of 2D nanomaterials. (a) Three dissolution mechanisms in biological and environmental media. (b) Equilibrium solubilities of metal sulfides, oxides, hydroxides and LDHs at pH 7 based on solubility constants for metal hydroxides and LAHs,203 or Visual MINTEQ 3.1 for metal oxides and sulfides at pH 7 with 1 mM NaNO3 as electrolyte.205 (c) Criterion for oxidative dissolution: comparison of 2D material oxidation potentials with the water/O2 redox couple (pH 7), suggesting that MoS2, MoSe2, WS2 and WSe2 are likely to be oxidatively unstable. (d) Criterion for reductive dissolution: comparison of 2D material reduction potential with the cellular redox potential (exemplified by GSH/GSSG couple) at pH 7, suggesting WO3, MoO3 and MnO2 are unstable to biological reduction and dissolution.

Material dissolution can occur by simple processes that do not involve changes in oxidation state, namely ion dissociation or hydrolysis, often promoted by acidic or basic conditions. Figure 7b shows solubilities by this simple (non-redox) mechanism for an example set of layered materials in simple media at pH 7. Some materials show high solubility and are thus not stable in dilute suspension, and convert completely to soluble forms. Other materials show lower solubilities (in mM range) that may allow the materials to persist in solid form, but will create a co-existing ion pool at mM concentrations, which is sufficient for many metals to show toxic effects (e.g. Zn, Ni, Mn191, 195). Several materials in Fig. 7b show very low solubilities (MoS2, MnO2), but interestingly these two will be shown to dissolve anyway because they participate in oxidative and reductive pathways respectively (next section).

In Figure 7b, MoO3 and WO3 are known to be thermodynamically unstable and readily hydrolyzed into molybdate and tungstate, respectively (e.g. ) in relatively high pH solution.198, 199 Thus the equilibrium concentration of MoO3 and WO3 at pH 7 are estimated based on the solubility of sodium molybdate and sodium tungstate, respectively.200 Acidic conditions have been reported to slow the hydrolysis process of MoO3 since increased proton concentrations shift the above reaction to the left.201 Below pH ~2, MoO3 is reported to be very stable against hydrolysis.202 The equilibrium concentration of metal hydroxide (Zn(II), Co(II), Ni(II)), and their corresponding Fe(III)-based LDHs in the form of M(II)2Fe(III)(OH−)6Cl− are calculated based on published solubility product constants, which indicate the 2D LDHs are even less stable than the corresponding metal(II) hydroxide raising the concerns about their toxicity.203 Kaolinite and TiO2 have low solubilities and their biological effects are not thought to depend on associated ions.

Fig. 7c and d use oxidation/reduction potentials for layered materials to anticipate the ability of 2D forms to undergo oxidative/reductive dissolution. This presentation follows the approach of Chen and Wang204 used to predict the ability of compound semiconductors MX (e.g. M=Mo, X=S2 in MoS2) to decompose through acquisition or loss of electrons as in the generic half reactions:

| (Oxidation) |

| (Reduction) |

where G is the Gibbs free energy of the compound at the standard state, e is the elementary charge and F is the Faraday constant.

This defines the thermodynamic oxidation potential φox and reduction potential φre, which can be obtained from published thermodynamic data.200, 204, 206–209 A 2D material is thermodynamically able to undergo oxidation in aerobic biological environments if its φox value is lower (more negative) than that of the oxygen/water redox couple φ(O2/H2O), and Fig. 7c shows that such oxidation is thermodynamically favorable for TMD materials. Bulk forms of TMDs are reported to be kinetically resistant to complete oxidation due to the formation of a passivating oxide layer,210, and even TMD thin films require a strong oxidizer and high temperature for their effective etching.211, 212 It is likely that the ultrathin 2D forms will not form passivating oxide films, and that the oxidative dissolution that is thermodynamically favored (Fig. 7c) would take place readily. Currently dissolution studies on 2D forms are very limited,213, 214 and experimental research work on this topic deserves to be a high priority.

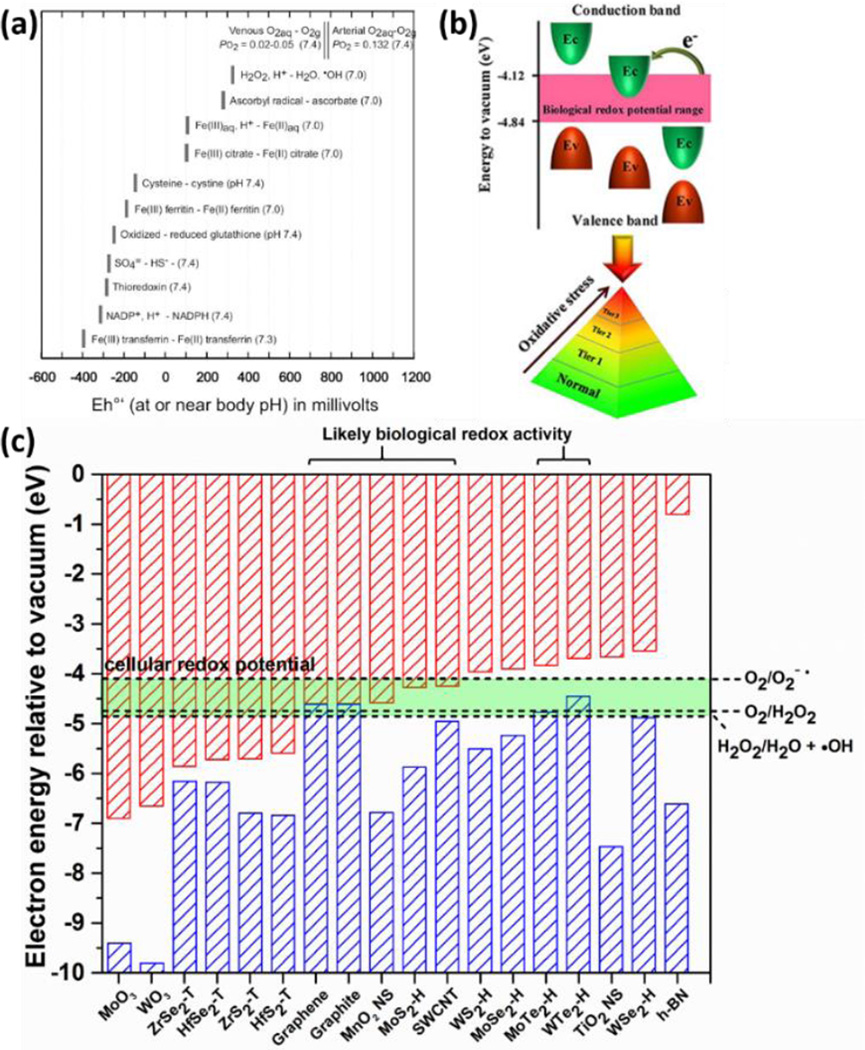

The reductive pathway to dissolution has received less attention in the nanotoxicology literature. Although biological media contain a variety of reducing agents, little is known about their effects on nanomaterial stability or ion release. Recently, the redox behavior of semiconducting nanomaterials has been correlated with the position of their conduction band edges to the cellular redox potential, which is estimated by the range of potentials in a set of significant biomolecular redox couples.192 (see Fig. 10). Here we use the cellular redox potential to assess the ability of biological fluids to chemically reduce 2D materials to soluble products. Figure 7d compares the cellular redox range with reduction potentials for an example set of layered materials, and shows that WO3, MoO3 and MnO2 are thermodynamically favored to undergo reductive dissolution. Indeed the literature reports degradation/dissolution of MnO2 nanosheets16 and this behavior has been used as a tool for intracellular glutathione detection.215 The reduction kinetics of colloidal MnO2 by cysteine and glutathione have also been studied, and the reaction products were identified as Mn(II) and corresponding disulfide.216

Figure 10.

Band structures of 2D and bulk layered materials, and band alignment with the cellular redox potential and the ROS-involved redox couples. (a) Cellular redox potential range defined by biomolecular redox couples. Reprinted with permission from ref. 323. Copyright 2006 Mineralogical Society of America. (b) The illustration of platform for modeling of structure–activity relationships based on band structures. Reprinted with permission from ref. 192 Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society. (c) The comparison a physicochemical in silico screening tool for identifying specific 2D materials with high potential for biological redox activity. Construction of the framework is based on published data in graphite,331 single wall carbon nanotubes,332 TMD,333 h-BN,334 MnO2 nanosheets,335 lepidocrocite-type TiO2 nanosheets,336 MoO3 and WO3,337 and ROS-involved redox couples.338

Finally, dissolution processes have important implications for biological response and risk. Materials that dissolve readily will be non-biopersistent, and this excludes certain pathogenic responses associated with long-term exposure to persistent particles in the lung or pleura, such as those that give rise to long-latency diseases such as lung fibrosis (asbestosis) or cancer (malignant mesothelioma). On the other hand, dissolution produces soluble species of high-bioavailability that can exert acute toxic effects. The relative importance of these competing effects of dissolution depends sensitively on the intrinsic toxicity of the soluble species, which in turn is closely related to the composition of the 2D material in question. 2D materials that dissolve into low-toxicity species (silicic acid, molybdate anion) can be reasonably anticipated to show low toxicity.

Overall, this review strongly suggests that many 2D materials will undergo biological dissolution (metal chalcogenides, some oxides and hydroxides) in the oxidative, reductive, or simple (non-redox) modes, and will thus not persist in their original solid state. There is critical need to confirm this analysis for monolayer and few-layer materials, and to characterize the dissolution processes (kinetics and product distributions), which can be coupled with information on the intrinsic toxicity of the soluble products to predict toxicity and manage risk. From a broader perspective, understanding the biological behavior of 2D materials will require much more research on their dynamic evolution in living systems, including not only dissolution, but also degradation, phase transformation, molecular adsorption events, and alterations in physical structure and edge states.

Surface states and molecular adsorption / exchange

The extraordinary high surface areas of mono- and few-layer nanosheet materials may not only accelerate dissolution processes, but may also lead to high chemical reactivities and adsorption capacities/rates relative to many other common nanomaterials. The surface chemistry of nanosheet materials must be understood in terms of their 2D geometries. Unlike the reactive, cleaved surfaces of 3D α-quartz (Fig. 5c), cleavage of 2D materials is typically a physical exfoliation that does not (necessarily) involve bond rupture and creation of nascent active sites. Nanosheet materials without crystalline defects may be expected to show low reactivities on their basal surfaces for many chemical processes. In contrast, the edge planes of 2D materials often involve unsatisfied valencies, or are decorated by extrinsic functional groups that result from environmental interactions of those unsatisfied bonds during synthesis or processing. This logic might suggest edge-dominated chemical reactivity in 2D materials, but this is not clear due to the large basal/edge ratio that is intrinsic to high-aspect-ratio sheet mono- or few-layer sheets (e.g. those of extended lateral dimension). Here the geometric area is dominated by the faces, which may have covalently-satisfied atomic planes in ideal form, but in most materials contain defects. The low edge/basal area ratio in ultrathin materials may result in basal defects driving much of the reactive surface chemistry.

An example of 2D material reactivity governed by basal defects is the MoS2 oxidation study of Yamamoto et al.,217 that uses AFM to track nucleation and growth of O2 etch pits in large monolayer MoS2 flakes on silica substrates. When organo-lithium intercalation is used for chemical exfoliation of TMDs, the resulting nanosheets are reported rich in internal edges (e.g. basal defects) due to the violent rupture process, and to possess high affinities for thiol groups shown by both experiment 218 and modeling.219 As a result, chemically exfoliated MoS2 can be easily functionalized with thiol-terminated ligands for applications.218 Thiol-terminated polymers (e.g. lipoic acid modified PEG) can be grafted onto MoS2 nanosheets through such thiol reactions to increase colloidal stability and biocompatibility for biomedical applications.123

Another behavior that is characteristic of layered materials is ion exchange to/from interlayer spaces. Layered double hydroxides, for instance, are anionic clays composed of trivalent cation substituted brucite-like layers with positive charges, compensated by exchangeable anions between layers. The high anion exchange capacity of LDHs has been utilized for the removal of anionic contaminants such as phosphate,220 fluoride ions,221 herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate.222 The adsorption process is strongly dependent on the nature and content of di- and trivalent cations, and higher initial content of trivalent cations usually possess larger adsorption capacity.220 Anionic molecules of larger size (e.g. sodium dodecylsulfate) can also be incorporated into LDH interspace via ion exchange.223 Other clays such as montmorillonite and vermiculite have exchangeable interlayer cations, and can be low-cost natural sorbents for heavy metal ion removal.224–227 Vermiculite has been reported to adsorb heavy metal ions primarily at planar sites via cation exchange but also at layer edges through formation of complexes with oxygen-containing groups.227