Abstract

Objectives

Type 1 diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood. Active parental involvement, parental support in the diabetes management and family functioning are associated with optimal diabetes management and glycemic control. The purpose of this study was to assess parental satisfaction with participation in the group and their perceptions of the impact of the intervention on living and coping with childrens T1D.

Methods

A sample of 34 parents of children with T1D participated in this trend study. The participants’ experience and satisfaction with support group was measured by a self- evaluation questionnaire, designed for the purpose of the present study.

Results

Quantitative data show that parents were overall satisfied with almost all measured items of the evaluation questionnaire (wellbeing in the group, feeling secure, experiencing new things, being able to talk and feeling being heard) during the 4-year period. However, parents from the second and third season, on average, found that the support group has better fulfilled their expectations than the parents from the first season (p = 0,010). The qualitative analysis of the participants’ responses to the open-ended questions was underpinned by four themes: support when confronting the diagnosis, transformation of the family dynamics, me as a parent, exchange of experience and good practice and facing the world outside the family.

Discussion

The presented parent support group showed to be a promising supportive, therapeutic and psychoeducative space where parents could strengthen their role in the upbringing of their child with T1D.

Keywords: mothers, fathers, emotional regulation, family functioning, relational family model

Abstract

Izhodišče

Sladkorna bolezen tipa 1 je ena izmed pogostejših kroničnih bolezni v otroštvu. Optimalno vodenje in presnovna urejenost otrokove sladkorne bolezni sta povezana z aktivno vključenostjo staršev/skrbnikov, podporo otroku pri nadzoru nad boleznijo in funkcionalnostjo družine. Raziskava predstavlja oceno zadovoljstva staršev s programom skupine za starše in njihovo doživljanje vpliva omenjenega programa na življenje otroka in spoprijemanje z njegovo SBT1.

Metode

V raziskavi je sodelovalo 34 staršev otrok s SBT1. Udeleženci so izpolnili evalvacijski vprašalnik o izkušnji in zadovoljstvu s skupino za starše, ki je bil sestavljen za namen te raziskave.

Rezultati

Kvantitativni podatki so pokazali, da so bili starši v splošnem zadovoljni pri skoraj vseh merjenih postavkah (počutje v skupini, občutek varnosti, odkrivanje novih stvari, možnost pogovora, občutek slišanosti) v štirih sezonah skupine za starše, razen pri postavki izpolnitev pričakovanj. Udeleženci iz druge in tretje sezone so poročali, da je skupina izpolnila njihova pričakovanja v večji meri, kot pa so o svojih pričakovanjih poročali udeleženci iz prve sezone (p = 0,010). Kvalitativna analiza odprtih vprašanj je pokazala štiri teme: opora skupine pri soočanju z diagnozo SBT1, preoblikovanje družinske dinamike, vzgoja otroka s SBT1, izmenjava konkretnih izkušenj in dobrih praks ter soočanje z okoljem. Tema »opora skupine pri soočanju z diagnozo SBT1« je prevladujoča v vseh štirih sezonah.

Razprava

Skupina za starše se kaže kot pomemben terapevtski, podporni in psihoedukativni dejavnik; v njej starši ob voditeljih in drugih udeležencih krepijo svojo pomembno vlogo, ki jo imajo v življenju otroka s SBT1.

1 INTRODUCTION

A diagnosis of chronic illness, such as type 1 diabetes (T1D), in a child, has a substantial impact not only on the child’s life but on the entire family (1). Parents have the key role in coping with the new way of life not only as caregivers but also as regulators of the child, and their own emotions influenced by chronic illness and the loss of a healthy child. Relevant literature shows the importance of parental role and experience in coping with T1D (2–4).

T1D is a chronic illness caused by autoimmune destruction process of insulin producing pancreatic β cells, and is characterized by persistent hyperglycemia (5, 6). Treatment regimen includes frequent blood glucose monitoring, appropriate adjustments of insulin doses that match carbohydrate intake, exercise and stress. Daily self-management regimen is crucial to maintain optimal health, to avoid the most frequent acute complications such as high- (hyperglycemia) or low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and, in the long run, also reduces the risk of long-term complications (5, 7, 8). The entire family has an important role in daily routine of careful self-management (9). Optimal metabolic control is associated with greater family cohesion (10, 11) and lower family conflicts (2–4, 12). Research shows that parents hold a high level of responsibility, are the main source of the child’s support and an important link between the child and the health care team in diabetes management (1, 13). Continuous parent involvement that results in frequent blood glucose measurements is associated with better quality of life and metabolic control in children, but also with higher anxiety and stress in parents (14–17), especially in parents of younger children (18, 19) and mothers of children and adolescents (15). Mothers are more concerned and report greater fear of hypoglycemia (16, 20), parental stress, feelings of depression and diabetes burnout than fathers (15, 17, 21). These findings support the need for parent-based interventions that reduce parent distress while improving coping and supportive involvement (22–24). Studies show that support and psychoeducation groups for parents of children with T1D may decrease the influence of stressful treatment management and improve the quality of life in the sense of emphasizing the provision of information (knowledge about diabetes and general principles for management), or teaching specific coping skills to accomplish increased competence in medical management.

Relational Family Therapy (RFT) is a psycho-biological model based on the assumption that various patterns (of early relationships with parents, physical, emotional and behavioral sensations) are restoring throughout the life cycle on the systemic, interpersonal and intrapsychic level (25). Through interpersonal and systemic matrix of family relationships, members learn and develop skills of functional communication and emotion regulation. Parents of children with T1D find themselves in an entirely new role, and must regulate the child’s physical (medication, food, rest) and psychological states (level of stress, emotions), as well as cope with the world outside their families (kindergarten, school, friends, co-workers, etc.), which may lead to the feelings of unacceptability, misunderstandings, guilt, anger and sadness (26). The Relational Family Model traces the mechanism of affect regulation, which plays an important role in the balancing of parental intrapsychic level of experiences as well as experiences in the parent-child relationship. The process of affect regulation may help a parent to identify and regulate her child’s distress, influenced by the chronic illness, transform it into a form that is manageable and acceptable for a child, and explore new meanings of the illness (27, 28). The impact of T1D on the entire family directs the need for parent-centered interventions to reduce distress and improve mental health, psychological adjustment and coping.

The present study reports the experiences of the parents of children with T1D enrolled in the parent support group. The purpose of this study was to assess parental satisfaction with participation in the group and their perceptions of the impact of the intervention on living and coping with their children’s T1D.

2 METHODS

2.1 Parent Support Group

The parent support group was designed to provide psychosocial support for parents of children with T1D. The program started in 2010, in collaboration with The Department of Endocrinology Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at University Children’s Hospital, Ljubljana, Association for children with metabolic disorders and Franciscan Family Institute. The support group program is based on the relational family paradigm (27), and takes into account the specific dynamics of the family systems with children with chronic illnesses (29, 30). The primary aim of the program is to create a space for awareness, understanding and development of more flexible and adaptive coping strategies for regulating stressful emotions influenced by child’s T1D, and to empower parents to be sensitive to their own and children’s needs (30–32). The key objectives of the program are to help parents reflect their role as parents, to enhance ‘attunement’ to children’s needs, connection and deeper understanding between a parent and child (31), as well as to improve their own coping and ability for effective and functional living with the child’s diabetes. The content of the program was accentuated to parents’ challenges in living with the child’s T1D from diagnosis onwards, experiences of responsibility and daily stress related to diabetes management, coping with emotions and worries, their view of child’s experience of T1D and challenges in adolescents with T1D (e. g. rebellion, setting limits), as well as family adjustment, communication, relationships and support. The therapists used group and psychotherapeutic intervention techniques, such as problem-solving skills, feedback, modeling, the validation of feelings with further questions in collaboration with all the other participants in search of alternative solutions to a concrete situation. Nine monthly sessions, from September to May, of 2 hour duration, were facilitated by a therapeutic pair of trained marriage and family therapists. The setting of the group was of a closed type for the first three seasons and of an open type for the final season.

2.2 Participants

Forty-seven parents (32 mothers, 15 fathers) of 33 children with T1D participated in the support group on at least one of the four seasons from January 2010 to May 2013. Participating parent’s average age was 42.4 years (SD = 6.9), their child’s average age was 8.9 years (SD = 5.04). The average duration of child’s T1D at the parents’ inclusion in the support group was 1.6 years (0 years–10 years; SD = 2.59). The drop-out rate during the first three seasons was four of 21 families. The reasons stated were the change of working times or birth of a new child. Nine families attended the group for two seasons, and one family for three seasons.

The self-evaluation questionnaires were returned by four out of six participants in the first season (2009/10), 11 of 15 participants in the second season (2010/11), 10 of the 12 participants in the third season (2011/12) and by nine of 22 participants in the final (open group type) season (2012/13).

2.3 Self-Evaluation Questionnaire

The self-evaluation questionnaire was designed by the authors for the purpose of the present study, and consisted of two parts. The first part of the questionnaire was related to the parents’ well-being in the group. Parents answered to the questions such as ‘I felt safe in the group’ and rated each of the six items (feelings, expectations, safety, new knowledge, an opportunity to speak and the feeling to be heard) on a five-point Likert scale from 1 - not at all true to 5 - absolutely true. In the fourth season (2012/13), the participants were also asked to quantitatively evaluate the organizational aspect of the group (topics of the meetings, the organization of meetings and the team) on the scale from 1 - very poor to 5 - very good. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions, regarding: the topics that were of the most interest to the participant; the effect or changes that the group might have brought to the participant, to his/her partner or child; the comments on the group organization and structure; the aspects of the group that the participants liked, or the aspects they would change in the program in general.

2.4 Participation in the Parent Support Group and Analyses of the Data

The parents were informed and invited to the support group by the Association for children with metabolic disorders and at the regular outpatient visits at The Department of Endocrinology Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases, University Children’s Hospital, Ljubljana. The participation in the group was voluntary. At the first meeting, the parents signed the informed consent of participation in the group and completed the demographic questionnaire. At the final meeting of each group season, the participants were invited to complete the self-evaluation questionnaire. All information about the members was used only for the purpose of the group and present research. The study protocol was approved by the National Medical Ethics Committee (Approval No. 122/04/10).

The quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS software version 19. The Brown-Forsythe test was conducted to compare the differences between the average scores of the first three seasons. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyse differences between the third season of the closed group (2011/12) and the open group season (2012/13). The differences were considered statistically significant at the p < 0,05. The qualitative data was analysed using content analysis (30). All of the participants’ answers were grouped into themes by way of a cyclical process of reflection, observation, and analysis by the consensus of two researchers. Illustrative examples for each theme were then used in the paper.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Group Attendance

The mothers were more than twice as frequently present as the fathers (154 versus 74). The fathers attended the group more frequent than the mothers only in seven of 33 families. More parents visited the open group than the closed group - the open group was attended by 22 parents (2012/13), and the closed group, in the first season (2010), was attended by 9 parents, 14 parents in the second (2010/11), and 16 parents in the third season (2011/12). However, a smaller core of parents was formed within the open group (7 parents), which attended the group throughout the year.

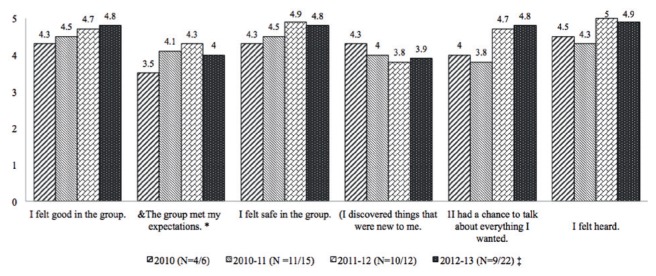

3.2 Questions on Wellbeing in the Group

Parents in the group were overall satisfied with regards to all six items of the questionnaire (Figure 1). The results show a statistically significant difference with regards to the item ‘expectations’ (F (2, 22) = 5,757, p = 0,010), namely: parents from the second and third season, on average, found that the support group has better fulfilled their expectations than the parents from the first season. Regarding other items, there were no statistically significant differences on: wellbeing in the group (F (2, 22) = 0,761, p = 0,479), feeling secure (Welch F (2, 6,722) = 2,743, p = 0,135), experiencing new things (Welch F (2, 7,090) = 0,331, p = 0,729), being able to talk (F (2, 22) = 2,158, p = 0,139) and the feeling of being heard (Welch F (2, 6,761) = 2,166, p = 0,188).

Figure 1.

Parent support group questionnaire mean scores in parents of children with T1D by seasons (1 – not at all true, 5 – true to a great extent).

Note:‡the group was of a closed type in the seasons 2010, 2010–11, 2011–12 and of an open type in 2012–13, * the difference is statistically significant.

There were also no statistically significant differences between the last season of the closed group (2011/12) and the season of the open group (2012/13) on any of the items: wellbeing in the group (M-W = 48,50, p > 0,05), expectations (M-W = 10,50, p > 0,05), feeling secure (M-W = 39,50, p > 0,05), experiencing new things (M-W = 46,00, p > 0,05), being able to talk (M-W = 48,50, p > 0,05) and the feeling of being heard (M-W = 44,50, p > 0,05).

3.3 Questions on Organization and Subjects

The parents in the season 2012/13 (N = 9) also completed the questionnaires about the organisation and subjects discussed in the group. Their average score pertaining to the item on subjects discussed in the group (relevance, importance) was 4.4, their average score pertaining to the item regarding organisation (time, location, informing) was 4.7, and pertaining to the item regarding group leading (attitude of group leaders, moderating, giving feedback) was 4.7.

3.4 Open-Ended Questions

The participants’ responses to the open-ended questions are grouped according to similar topics, and illustrative disclosures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Disclosures of the participants of the parent support group, according to the most relevant emerging themes.

| Disclosures of the participants of the parent support group, according to the most relevant emerging themes. | One thing is what you read in the literature and what doctors and nurses tell you. And another thing is what other parents tell you … The parents who, by themselves, calculate, weight, inject and question themselves if they are doing it the right way. And who answer their children ‘why’ and ‘how’ to go through the disease that will stay with them forever. It is much easier to share our sorrow and joy of our ‘sugarplums’ (child with T1D) growing up in a group of parents with the same stories. I would like to welcome ‘the new family member’ (the disease), so that I could face the difficulties and the struggle of living with the disease. |

| Transformation of the family dynamic | Diabetes is a good teacher. It forces the family into better relationships, so that the family can survive as a whole. You devote to your child more fully and in a different way. It takes a lot of discipline, determination and persistence. When you accept diabetes into your life, it can give you a lot of positive things. But I definitely don’t neglect all of distress that accompanies that. I could tell my husband what I experience about the disease and I could also hear what my husband experiences. |

| Me as a parent | … (The most valuable thing is) to meet other people with the same problems regarding diabetes management, and to see that you are not alone with the problems and that you can get along with the disease. Oh, yes, I would say a lot (changed in him as a parent). I am more tolerant, better educated and prepared for problems that may emerge in the future. And what I think the best outcome of the group is: despite of the reality of living with my son’s T1D and a heap of limitations and regulations because of this, the life and coping with daily things is simpler and better – less stressful and tiring. … in the situation when ‘you lose control,’ I can calm down much easier and count to 10 before I respond. |

| Exchange of experience and good practice | Exchange of experiences, how to respond in different everyday situations (was very important). (A great value in) … expert help of the group and qualified group leaders. I have more information about everything - upbringing and living with my son’s diabetes. One has so much faith in those words, you just absorb them. What she (the doctor) says is as if you hear this for the first time, even though you have heard this often. |

| Facing the world outside the family | This group means a lot to me because I feel I am accepted and understood. I miss that in my everyday life, with co-workers, friends … |

Support when confronting the diagnosis

One of the most important themes that emerged was the feeling of emotional support and being understood by the other parents that are in a similar situation.

Transformation of the family dynamics

T1D requires adjustments of a family by re-shaping the family member roles and their dynamics (i.e. time that parents spend with the child with T1D, other children and with each other; time for everyday activities; family roles and burden of responsibility of every family member, etc.), and also to re-establish adequate relationships to the world outside the family (i.e. kindergarten, school, friends and relatives, etc.). In most of the families, the mothers took over the majority of the burden of T1D. The fathers, on the other hand, distanced themselves from emotional burden and focused on more technical aspects of family functioning (finances, logistics, etc.).

Me as a parent

The participants serve each other as models of emotion regulation. In this way, they got a better insight into more or less functional strategies of coping with distress. For most, this was a very valuable experience. They experienced the group as a space where they could evaluate their part in disease management, their experience of different emotions, and as a space where they got enough emotional support, so that they could respond to their children’s emotional problems and challenges of growing up with T1D.

Exchange of experience and good practice

The participants pointed out the need for practical solutions to the problems of living with T1D. Some of them found value especially in expert information. Furthermore, the visit of the paediatric diabetologist turned out to be especially appreciated and valued.

Facing the world outside the family

The participants experienced the group environment supporting and understanding, as opposed to their communities (friends, family, work).

4 DISCUSSION

The article presents a quantitative assessment of the participants’ satisfaction with the support group for parents of children with T1D, and a qualitative exploration of the perceived impact of the group to their functioning.

In all of the seasons, the parents experienced the support group as a safe space where they could connect, talk and also be heard about their challenges and feelings.

According to the Relational Family Model, a sense of security is essential for a functional affect regulation (24, 25). For the parents of children with T1D, the biggest challenge is to accept the disease and transform their relationship to the children’s diabetes. The ability of a family’s coping with difficulties of a child’s T1D depends on the mental health of the parents (14–17, 20, 31).

When considering a sense of security, it is important if the group is open or closed. In our instance, in the first three seasons, the group was closed so that only the members from the first meeting could attend the meetings. The only significant difference between these seasons was with regards to the item expectations. The lowest score was in the first season, which can be explained by the fact that the program of the group developed through the seasons so that the needs of the parents could be better met. When comparing the last season of the closed group (2011/12) with the season of the open group (2012/13), there was no statistically significant differences on any item. That indicates that, also in the open group, when the parents could join the group at any meeting, the parents felt that they can express themselves and be heard. Possibly, this means that the closeness of the group is not the most important factor for the parents’ feelings of security. The detailed analysis of attendance of the season 2012/13 revealed an establishment of a smaller group of parents who regularly attended the meetings, possibly contributing to a stronger sense of security among new members. Moreover, the experience of being a parent of a child with T1D could contribute to a stronger and faster development of the feelings of empathy and understanding among the members. The f finding was supported also by their reflections.

The participants also evaluated the organisation of the open group in the last season. The results of the questionnaires indicated that parents found the open group setting with monthly two hour meetings suitable.

The mothers visited the support group twice as frequently as the fathers. The reason could be a greater engagement of the mothers in the responsibility and care for a child with T1D, a finding in accordance with other research (3, 15, 16). In the study by Streisand et al., 79 % of the mothers took care for injecting the insulin and, in 70 % of the cases, they took care for blood glucose measurements (15). The fathers’ generally lower involvement in the process of disease management is also connected with worse treatment outcomes in adolescents with T1D (3, 16).

The topics the participants pointed out in the evaluation questionnaires are in accordance with the themes other researchers found to be important for the parents of children with T1D (27). The participants pointed out that emotional support of other parents was the most important benefit of the group. This finding is in line with their feelings of social isolation, loss of the healthy child and, consequently, the way of life they used to know. When their child is diagnosed with T1D, the family life changes dramatically. Because of the constant threats of hypoglycaemia and a fear of complications, later in life, the parents are overwhelmed with emotions of sadness, fear, anger, guilt, which often isolates them from a wider social network (17, 20, 21). They are faced with a completely new challenge of regulating their children’s physical (food, rest, blood sugar) and psychical states (stress, emotions). Moreover, they must communicate their new circumstances and needs to a wider community (relatives, friends, school or kindergarten, co-workers, etc.), which can trigger new feelings of alienation, misunderstanding, guilt, anger and overall stress (20).

Parents have also noticed that the group helped to improve their family dynamics. T1D influences a family profoundly: the roles in the family change, the hierarchy changes, also communication, interpersonal relations and finances (13, 27). The child and also other family members must learn to regulate the effects through their interpersonal relationships. Good family functioning and coping with challenges of T1D leads to a better glycemic control (10, 11). On the other hand, conflicts, unclear boundaries between family systems, unclear or rigid rules and undefined roles in the family lead to worse diabetes management and glycemic control (2–4, 12). Relational family model asserts that dysfunctional family system achieves its homeostasis by transmitting tension to the child who becomes a carrier of unresolved family conflicts, and is therefore unable to functionally express and regulate emotions (23, 32). This is especially crucial in the families with children with T1D. When evaluating the group, one of the mothers pointed out that she could express to her husband what she felt and also that she could hear what he was experiencing. In the functional regulation of emotions in the family, it is crucial for the parents to be heard and understood among themselves. Their interpsychic and interpersonal emotion regulation, furthermore, enables them to feel the child’s distress and help to regulate it and transform it into a form the child can manage (24, 25).

The parents felt more competent in their upbringing after attending the group, as a consequence of gaining new knowledge and exchanging good practice in the management of diabetes, which they got from other parents as well as from the group leaders and the diabetologist. The perceived change helped them to adapt to new circumstances of their family, reduced the anxiety and stress in the family, which are all important themes in the families with T1D (27). Another important aspect that the participants perceived as helpful in the family’s adaptation to the disease was open communication between the diabetic team and the family members. Communication about the possible disease complications and the accompanying emotions is very important for the family in order to be able to accept the new situation of living with the T1D, to try to find the meaning in the disease and to start to live anew (33). In other words, the parents, in the management of their children’s T1D, do not become just medical experts and dietetics for T1D, but remain the most important regulators of all difficult emotional states that T1D awakes in the child and other family members.

However, a few limitations of the study should be considered. There were no standardised measures used in the study which would more accurately indicate the process of the group and specific differences and changes in the parents’ experiencing pre- and post-intervention. Additional data about children’s psychosocial and diabetes characteristics were lacking, which could show a potential pathway to the parental coping with the child and T1D, and thereby limiting the analysis of the results.

5 CONCLUSION

The research in the field of psychological support for parents with chronically ill children is scarce. T1D is a big challenge, not only for the child, but also for other family members facing this new physical and emotional state. The parent support group helps the parents to express their concerns, to give support to one another and, especially, to recognise, accept and regulate their children’s physical and psychological changes and needs. The presented parent support group showed to be a promising supportive, therapeutic and psychoeducative space, where parents could strengthen their role in the upbringing of their child with T1D. Effective psychosocial support to families is a part of integrative healthcare in children and adolescents with T1D.

For the future work of the support group, it would be important to employ a quantitative analysis of the changes in the experience of the parents, using standardised measures, and to follow the process and the dynamics of the group.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

FUNDING

The study was financed in part by EU-CDEC project number 2013-1-GB2-LEO-05-10755, and Slovene National Research Agency Grants J3-9663, J3-2412, J3-4116 and P3-0343.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Received from the Slovene National Medical Ethics Committee (Approval No. 122/04/10).

REFERENCES

- 1.Snoek F, Skinner C. Psychology in diabetes care. 2nd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson B, Vangsness L, Connell A, Butler D, Goebel-Fabbri A, Laffel LMB. Family conflict, adherence, and glycaemic control in youth with short duration Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2002;19:635–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shorer M, David R, Schoenberg-Taz M, Levavi-Lavi I, Phillip M, Meyerovitch J. Role of parenting style in achieving metabolic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1735–7. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiebe DJ, Berg CA, Korbel C, Palmer DL, Beveridge RM, Upchurch R, et al. Children’s appraisals of maternal involvement in coping with diabetes: enhancing our understanding of adherence, metabolic control, and quality of life across adolescence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:167–78. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association AD . Standards of medical care in diabetes 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):11–66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyürüs E, Green A, Soltész G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratina N, editor. Sladkorčki: vse, kar ste želeli vedeti o sladkorni bolezni. Ljubljana: Društvo za pomoč otrokom s presnovnimi motnjami; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.DCCT Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delamater AM. Psychological care of children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:175–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen D, Lumley M, Naar-King S, Partridge T, Cakan N. Child behavior problems and family functioning as predictors of adherence and glycemic control in economically disadvantaged children with type 1 diabetes: a prospective study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:171–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis C, Delamater A, Shaw K, La Greca A, Eidson M, Perez-Rodriguez J, et al. Parenting styles, regimen adherence, and glycemic control in 4- to 10-year-old children with diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26:123–9. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsamparli A, Kounenou K. The Greek family system when a child has diabetes mellitus type 1. Acata Pediatr. 2004;93:1646–53. doi: 10.1080/08035250410018283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drotar D. Psychological interventions in childhood chronic illness. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewin AB, Storch EA, Silverstein JH, Baumeister AL, Strawser MS, Geffken GR. Validation of the pediatric inventory for parents in mothers of children with type 1 diabetes: an examination of parenting stress, anxiety, and childhood psychopathology. Fam Syst Health. 2005;23:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streisand R, Swift E, Wickmark T, Chen R, Holmes CS. Pediatric parenting stress among parents of children with type 1 diabetes: the role of self-efficacy, responsibility, and fear. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:513–21. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haugstvedt A, Wentzel-Larsen T, Graue M, Sovik O, Rokne B. Fear of hypoglycaemia in mothers and fathers of children with Type 1 diabetes is associated with poor glycaemic control and parental emotional distress: a population-based study. Diabet Med. 2010;27:72–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stallwood L. Influence of caregiver stress and coping on glycemic control of young children with diabetes. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monaghan MC, Hilliard ME, Cogen FR, Streisand R. Nighttime caregiving behaviors among parents of young children with type 1 diabetes: associations with illness characteristics and parent functioning. Fam Syst Health. 2009;27:28–38. doi: 10.1037/a0014770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton S, Dolan L, Henry R, Powers S. Fear of hypoglycemia in parents of young children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15:252–9. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9123-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landolt M, Vollrath M, Laimbacher J, Gnehm H, Sennhauser F. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:682–9. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000161645.98022.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streisand R, Mackey ER, Elliot BM, Mednick L, Slaughter IM, Turek J, et al. Parental anxiety and depression associated with caring for a child newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes: opportunities for education and counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:333–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schore A. Affect regulation and the repair of the self. New York: Norton; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkin K, Ahmad WI. Family care-giving and chronic illness: how parents cope with a child with a sickle cell disorder or thalassaemia. Health Soc Care Community. 2000;8:57–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gostečnik C. Inovativna relacijska družinska terapija: inovativni psiho-biološki model. Ljubljana: Brat Frančišek, Teološka fakulteta in Frančiškanski družinski inštitut; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gostečnik C. Relacijska paradigma in travma. Ljubljana: Brat Frančišek, Frančiškanski družinski inštitut; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couch R, Jetha M, Dryden DM, Hooten N, Liang Y, Durec T, et al. Diabetes education for children with type 1 diabetes mellitus and their families. Evi Rep Technol Assess. 2008;166:1–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whittemore R, Jaser S, Chao A, Jang M, Grey M. Psychological experience of parents of children with type 1 diabetes: a systematic mixed-studies review. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38:562–79. doi: 10.1177/0145721712445216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoey H. Psychosocial factors are associated with metabolic control in adolescents: research from the Hvidoere Study Group on Childhood Diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 13):9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel DJ, Bryson TP. The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child’s developing mind. New York: Delacorte Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snape D, Spencer L. The foundations of qualitative research. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaser SS, Whittemore R, Ambrosino JM, Lindemann E, Grey M. Mediators of depressive symptoms in children with type 1 diabetes and their mothers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:509–19. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smyth JM, Arigo D. Recent evidence supports emotion-regulation interventions for improving health in at-risk and clinical populations. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:205–10. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283252d6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gostečnik C. Sistemske teorije in praksa. Ljubljana: Brat Frančišek in Frančiškanski družinski inštitut; 2010. [Google Scholar]