Abstract

Background

The environments where parents spend time, such as at work, at their child's school, or with friends and family, may exert a greater influence on their parenting behaviors than the residential neighborhoods where they live. These environments, termed activity spaces, provide individualized information about the where parents go, offering a more detailed understanding of the environmental risks and resources to which parents are exposed.

Objective

This study conducts a preliminary examination of how neighborhood context, social processes, and individual activity spaces are related to a variety of parenting practices.

Methods

Data were collected from 42 parents via door-to-door surveys in one neighborhood area. Survey participants provided information about punitive and non-punitive parenting practices, the locations where they conducted daily living activities, social supports, and neighborhood social processes. OLS regression procedures were used to examine covariates related to the size of parent activity spaces. Negative binomial models assessed how activity spaces were related to four punitive and five non-punitive parenting practices.

Results

With regards to size of parents' activity spaces, male caregivers and those with a local (within neighborhood) primary support member had larger activity spaces. Size of a parent's activity space is negatively related to use of punitive parenting, but generally not related to non-punitive parenting behaviors.

Conclusions

These findings suggest social workers should assess where parents spend their time and get socially isolated parents involved in activities that could result in less use of punitive parenting.

Keywords: activity spaces, neighborhood social processes, punitive parenting, maladaptive parenting, non-punitive parenting, harsh parenting

Over the past few decades, neighborhoods increasingly have been seen as an important context for understanding parenting (Burton & Jarrett, 2000; Cuellar, Jones, & Sterrett, 2015; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Neighborhood social processes, or those interactions between neighbors that build social and supportive relationships, have been identified as one aspect of neighborhoods that could affect punitive and non-punitive parenting behaviors. Punitive parenting can include belittling, physical punishment or other actions involving aggression (Straus & Fauchier, 2011). In contrast, non-punitive parenting involves teaching the child the effects of their actions on others and the difference between right and wrong (Hoffman, 1983 in Van Leeuwen et al., 2012). Punitive parenting can include actions that would be considered child physical abuse, such as severe corporal punishment and other violence (e.g., hitting or kicking; Widom, 1989; Whipple et al., 1997), but not all punitive parenting practices are abusive (e.g., depriving a child of privileges).

Although neighborhood effects are present in cross-sectional studies, their effect sizes on parenting, including abusive or neglectful behaviors, generally tend to be non-significant or small in magnitude (Coulton et al., 2007; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). These small or null effects sizes occur regardless of how these residential neighborhoods are defined (e.g., neighborhoods with names, administrative units such as Census tracts, or common boundaries by neighborhood resident). One explanation for this is that focusing on residential neighborhoods (i.e., the geographic areas where people live) do not adequately capture where people, including parents, spend their time and the social conditions they encounter in the places where they do go (Browning & Soller, 2014; Inagami et al., 2007; Jones & Pebley, 2014; Matthews 2011). Some adults spend very little time during the week at their homes and within their defined residential neighborhood boundaries (Sastry et al., 2002). Thus, more realistically, the geospatial context of environments where parents do spend time, such as at work, at their child's school, or with friends and family, may exert a greater influence on their parenting behaviors. The study of these locations, termed activity spaces, provides individualized information about the where parents go, offering a more detailed understanding of the environmental risks and resources to which parents are exposed. Instead of focusing on the relatively small residential neighborhood areas where parents may or may not spend significant amounts of time, this study creates these activity spaces to see whether or not the geographic area of these spaces is related to the use of punitive and non-punitive parenting behaviors. Thus our study extends the concept of “neighborhood” by moving beyond residential neighborhood areas to capture those geographic areas where parents actually spend time during the course of their daily lives (Jones & Pebley, 2014).

Literature Review

Size of Parenting Activity Spaces

Despite the move from studying residential neighborhoods to activity spaces in the geography, public health, and demography literatures, research examining the size of activity spaces, particularly for parents, is emerging and limited. Activity spaces appear to be larger than either traditionally defined or individually perceived neighborhoods (Crawford, Jilcott Pitts, McGuirt, Keyserling, & Ammerman, 2014). For adults, having at least one friend in their neighborhood (as defined by the respondent) was related to having a smaller activity space, and moving in the past two years was related to larger activity spaces (Jones & Pebley, 2014). However, having at least one friend or family member in their neighborhood created a perception that the neighborhood was larger in size, compared to those who did not have someone close living in the neighborhood. For some adults (e.g., parents) this perception may lead to greater movement across a larger area of space both inside and outside the traditionally defined neighborhood areas (Sastry, Pebley, & Zonta, 2002). Adults who participated in a civic organization (e.g., neighborhood associations, political organizations or volunteer groups) reported larger neighborhoods than those who did not (Sastry et al., 2002). Taken together, people living in the same geographic area may not agree on what the boundaries of their neighborhood are and perceptions of the size of their neighborhood may be based on their own use of local space or the social relationships within those areas. Applying these findings to parents, smaller activity spaces may provide an assessment of social isolation for parents which may lead to punitive parenting, but this isolation may be negated if the same populations have greater access to resources like local friends or family and positive neighborhood social processes. We know little about activity spaces among parents, including whether or not these same features are related to the size of activity spaces for parents.

Parenting Practices, Activity Spaces, and Neighborhood Social Processes

In addition to the dearth of information about those elements that are related to the size of a parent's activity space, little is known about how activity spaces might be associated with parenting behaviors. Qualitative or mixed-methods analyses suggest that parenting may affect the activity spaces of mothers in particular (Noach, 2011; Kamruzzaman & Hines, 2012), who spend more time caring for children than fathers (Parker & Wang, 2013). However, recent quantitative data indicates there may be no difference in the size of activity spaces between those who have a child in the home and those who do not (Pebley & Jones, 2014).

Punitive parenting is associated with low levels of support and geographic isolation from support networks (Oates, Davis, Ryan & Stewart, 1979; Wolock & Magura, 1996; Coohey, 2007). Socially isolated parents may have few buffers from stress and less access to positive parent role models (Limber & Hashima, 2002; Thompson, 2014). However, social supports can also reinforce negative parenting practice, if parents are socializing with individuals who support punitive or abusive parenting (Emery, Nguyen, & Kim, 2014; Thompson, 2014). Recent evidence suggests that where a parent's social support lives (inside or outside the neighborhood) is related to parenting behaviors (Freisthler, Holmes, & Price Wolf, 2014). Thus parenting and social relationships have a geographic dimension.

Where a parent spends time during the course of their day could increase their exposure to positive or negative social supports and neighborhood social processes. Higher levels of neighborhood disengagement (defined as lack of community or neighborly involvement) have been related to less use of positive parenting styles (as measured by parental warmth, monitoring and behavioral control; Chung & Steinberg, 2006; Cuellar et al., 2015; Dorsey & Forehand, 2003). These neighborhoods may not afford opportunities for parents to interact with positive parenting role models. However, results have been mixed as to whether neighborhood social processes are associated with extreme punitive parenting (e.g., physical abuse). Early studies found no relationship between social processes and maladaptive parenting (Coulton, Korbin, & Su, 1999; Molnar et al., 2003). More recent studies have found that a composite measure of negative perceptions of neighborhood social processes (which included scales for social disorder, informal social control, and social cohesion) was related to more use of abusive parenting (Guterman et al., 2009) while neighborhood social disorder (as defined by the presence of a variety of neighborhood problems such as loitering, drug sales) was related to more frequent physical abuse (Author Citation). These findings suggest that parents living in areas with positive social processes may have lower rates of punitive parenting such as child abuse.

Framework for Understanding Activity Space Size and Parenting

Simple models of communicable disease might provide useful in understanding why the size of an activity space might be important for parenting. As one example, the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model suggests that of the spread of these diseases (e.g., flu, measles) are a function of the susceptible population (in this case all parents), the exposure rate of this population (which could be defined as either number of number of people supporting or disapproving of various parenting practices), the rate of already infected individuals encountered (defined by those using either punitive or non-punitive parenting behaviors), and the rate at which recovery occurs (e.g., changes in parenting practices from punitive to non-punitive or vice versa; Brauer & Castillo-Chavez, 2001; Kermack & McKendrick, 1927).

If we view positive parenting behaviors as socially “contagious”, parents with larger activity spaces may expose them to more individuals who may be likely to censure punitive parenting either through nonverbal communication or by contacting Child Protective Services to report abusive and neglectful parenting. In this case the “infection” would actually be the spread of positive parenting norms through more exposure to more non-punitive types of parenting behaviors or guardians who will criticize punitive parenting practices. More exposure to these individuals (through a larger activity space) may serve to change parenting practices such that more non-punitive practices are used. This study is the first step in understanding how the overall size of a person's activity across space might be related to these parenting practices. This social contagion phenomenon (e.g., modifying behavior to match that of peers) is predicated on the premise that even weak ties can influence behavior outcomes (Coiera, 2013; Granovetter, 1973; El-Sayed, Scarbourough, Seeman, & Galea, 2012).

This study conducted a preliminary examination of how neighborhood context, social processes, and individual activity spaces are related to a variety of parenting practices. The research questions in this exploratory study are: (1) What factors are related to the size of activity spaces for parents? and (2) Is the size of an activity space related to the use of punitive and non-punitive parenting practices? With respect to our first research question, we hypothesize that those who work outside the home, and those with a social support living inside the neighborhood will have larger activity spaces. For our second research question, we hypothesize that parents with larger activity spaces will use non-punitive parenting practices more frequently and punitive parents less frequently. Higher levels of perceived informal social control and reciprocated exchange will be related to more frequent use of non-punitive parenting practices and less frequent use of punitive parenting. By focusing on individuals living in a one small geographic area, this study inherently controls for the structure of the residential neighborhood.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected during door-to-door surveys as part of a larger survey on neighborhood life in a part of one neighborhood in Los Angeles, California. Study protocols were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles institutional review board. The week before surveys were to be conducted, members of the research team canvassed the area to leave preannouncement flyers at each home announcing the study and its purpose. A contact number was provided so that neighborhood residents could opt out of the study. Participants had to be at least 18 years of age to complete the 30 to 60 minute survey. Interviewers obtained verbal informed consent for each of the participants. Participants were given a $50 gift card to Target for participating in the interview. Dozens of potential survey participants contacted the research office using the phone number on the preannouncement letter to opt into the study (rather than opt out as was intended). From these phone calls, 57 survey interviews were conducted. The remaining 144 participants were obtained through the sampling procedures described below. The final sample size was 201. Of those, 42 were parents who were also primary caregivers of at least one child under the age of 12 and included in the analyses conducted here. The study had a 45% response rate for the sampled households.

The sample for this study was comprised largely of women (71%) with an average age of 43.4 years. The sample was highly educated with 38.1% having a Bachelor's degree and 38.1% having a more advanced graduate degree. Almost all (90.5%) of the respondents were married or in a marriage-like relationship and 69% of participants were Caucasian. Half of the survey participants reported working at least part-time. Over two-thirds of respondents reported yearly household incomes of over $100,000. This particular sample is more advantaged than many neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

Procedures

Households were sampled on randomly selected street segments in the study area. The study area was defined by four major streets (one on each side) and covered a .56 square mile area in Los Angeles, CA. The larger study, from which these survey participants were drawn, was sampled to understand how changes in the built environment might affect a variety of social connections and health behaviors. The study was conducted before a new public transportation railway line was to be built through the middle of this particular geographic area. The condensed geographic area was comprised of parts of two Census tracts and was a smaller part of a larger named neighborhood area.

For sampling purposes, each street segment was given a number. A street segment consisted of a block from intersection to intersection on each side of the street (North or South, and East or West) depending on where the street segment and side of street was located. The segments were sampled in random order until all homes either participated in the study, refused, or were not able to be contacted after four attempts.

Survey interviewers knocked on doors at each home in the sample segment, explained the study, and asked if an adult 18 years or older was interested in participating. If interested, the interview would either take place immediately or re-scheduled for a later date. If no one was home, another preannouncement flyer was left at the home. Each home was visited at least four times (varying the day and time of the visit) or until an interview was scheduled or potential respondents refused to participate. If more than one adult was interested in participating in the study, the adult with the most recent birthday was chosen. A household was considered eligible for inclusion in the study if it was located within the boundaries of the pre-determined study area and there was at least one adult over the age of 18 willing to participate. Individuals who were under the age of 18, who were not well enough to complete the survey, or did not speak English were excluded from the study. All of the surveys were conducted with a live interviewer in the home or other location of choice of the respondent. For those respondents with children under the age of 12, they were asked to select the child with the most recent birthday and provide responses to questions related to parenting behaviors and interactions among siblings.

Measures

The dependent measure was the use of various parenting behaviors from the Dimensions of Discipline Inventory (DDI). The DDI (Straus & Fauchier, 2011) measured the frequency of many of behaviors parents use to correct misbehavior. Twenty-six different behaviors are measured covering nine constructs of discipline including corporal punishment (e.g, How often did you spank, slap, smack, or swat this child?), deprivation of privileges (e.g., How often did you send this child to bed without a meal?), psychological aggression (e.g., How often did you shout or yell at this child?), penalty tasks and restorative behavior (e.g., How often did you give this child extra chores as a consequence?), diversion (e.g., How often did you put this child in “time out”?), explain/teach (e.g., How often did you show or demonstrate the right thing to do to this child?), ignore misbehavior (e.g., How often did you deliberately not pay attention when this child misbehaved?), reward (e.g., How often did you praise this child for finally stopping bad behavior or for behaving well?), and monitoring (e.g., How often did you check on this child to see if they were misbehaving?). The first four are considered punitive or harsh parenting while the remaining five are non-punitive discipline behaviors. Responses were: “Never,” “Not in the past year, but in a previous year,” “1-2 times in the past year,” “3-5 times in the past year,” “6-9 times in the past year,” “Monthly,” “A few times a month (2-3 times a month),” “Weekly (1-2 times a week),” “Several times a week (3-4 times),” “Daily (5 or more times a week),” and “Two or more times a day.” Reliability for the subscales ranged from .011 to .744. Frequency of each of the types of parenting behaviors was created by summing the number of times each behavior occurred within each subtype. For categories with a range (e.g., 3 – 5 times in the past year), the midpoint of the item was used. The frequency created referred to the number of times each subtype of parenting behavior occurred during the past year (i.e. ignored misbehavior 300 times in the past year). We do not have information on how the frequency for all types of parenting behaviors compare to other samples. However, we do know that the frequency of corporal punishment in this study (3.24 times per year) is similar to geographically-based studies that found parents use corporal punishment about 3.12 times per year (Freisthler & Gruenewald, 2013) in a sample of California parents and 3.64 times per year (Molnar et al., 2003) in a sample of parents in Chicago.

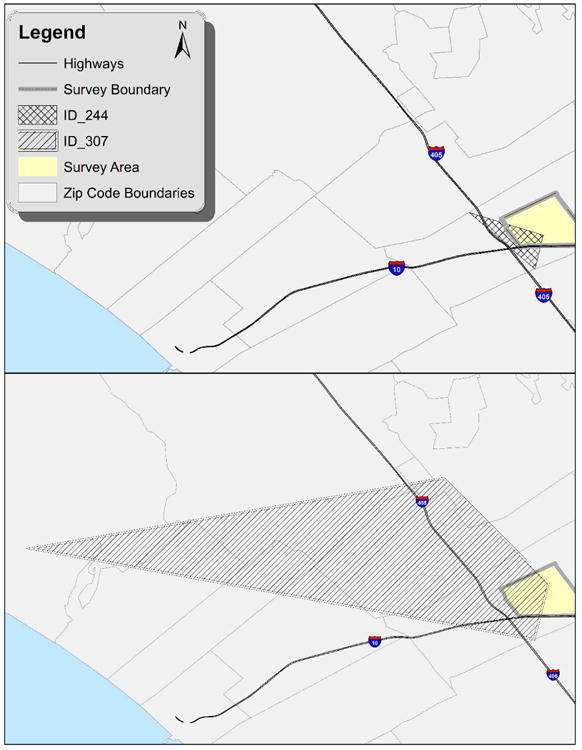

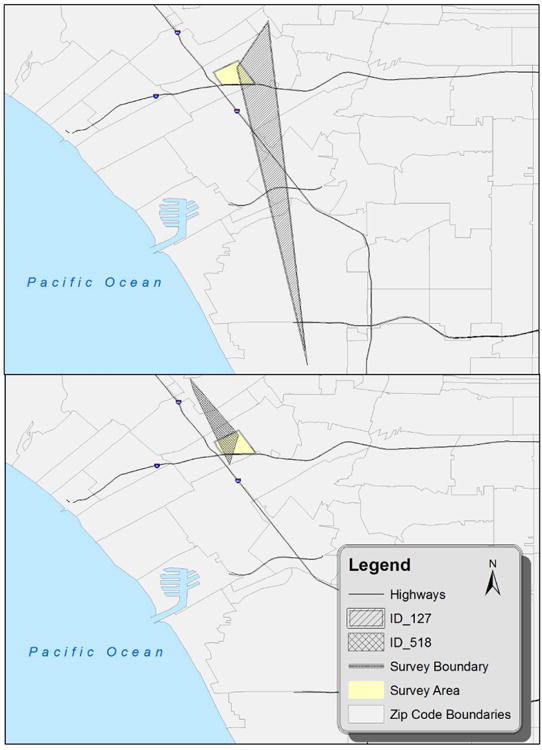

Activity spaces, defined as those areas where we live our day-to-day lives, was the dependent measure when examining what factors were related to size of parents activity spaces and as an independent measure to assess parenting behaviors. As each individual used different local resources, including work, different stores, doctor's offices, schools, etc., the size and location of an activity space is generally unique. We assessed each study participants individual activity spaces by asking them what grocery store they used most often, the location of their doctor, location of their children's school or day care, location of their favorite gym or coffee shop, location of their most supportive friend, and location of where they were employed. We mapped each of these points to create a polygon giving a general size of each person's activity space. We used “as the crow's flies” distance (e.g., straight line), not roadway networks to develop the activity space and measured the area of these polygons in square miles. Due to skewness, the natural log of the activity spaces were created and used for all analyses. Figures 1 and 2 present the depiction of four respondent's activity spaces. The use of activity spaces (vs. distance) allows us to assess “bigger” vs. “smaller” areas (more consistent with how residential neighborhoods are studied) where parents are traveling and is consistent with previous research conducted with larger sample sizes on activity spaces. That people often bundle activities together (e.g., go to the dry cleaners near the grocery store) is also recognized by this approach. Activity spaces allow us to identify the possible size of the spaces where social contacts occur that may ultimately affect parenting.

Figure 1. Activity Space Polygons for Two Similar Female Respondents.

Figure 2. Activity Space Polygons for Two Similar Male Respondents.

Social support was measured using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (Cohen, Mermelstein, Kamarck, & Hoberman, 1985). Twelve items assessed various aspects of social support, including having help with family, someone to talk over problems, and going to the movies with someone. Four response categories of “Definitely False,” “Probably False,” Probably True,” and “Definitely True” were used. Averages were constructed across all items for which participants provided responses (range: 1 to 4), with higher averages indicating higher levels of social support. Internal consistency reliability was high (α = .79).

Neighborhood social processes are measured through scales representing reciprocated exchange and informal social control. Reciprocated exchange refers to mutual exchange provided to families in a neighborhood, including watching each other's children, inviting neighbors to parties, and going to each other's housing (Sampson et al., 1999). In answering these questions, parents are providing their perceptions of reciprocated exchange in their self-defined neighborhood area (which may or may not correspond to official neighborhood boundaries.) Four items assess how often this occurred within the neighborhood: “Often,” “Sometimes,” “Rarely,” and “Never.” Cronbach's alpha assessing internal consistency reliability was .75. An average score was created for all the questions answered by the respondents (range: 1 to 4). Those respondents with higher averages reported higher levels of reciprocated exchange in the neighborhood.

Child-centered informal social control assessed the likelihood that neighbors would intervene in a child's antisocial behavior if they saw it occurring (Sampson et al., 1999). The four items included the likelihood of intervention is a youth was caught skipping school, spraying graffiti, fighting, and showing disrespect. The five response categories were “Very Likely,” “Somewhat Likely,” “Neither Likely nor Unlikely,” “Somewhat Unlikely,” and “Very Unlikely.” Responses were averaged (range: 1 to 5), with higher averages indicating higher levels of informal social control. Internal consistency reliability was measured at .65.

Participation in local organizations was assessed with three items. These items asked whether or not the respondent participated in any (1) local block clubs or neighborhood associations; (2) social clubs, sports teams, or fraternal groups; and (3) church related groups. A positive response to any of these questions was recoded as a “1” indicating participation.

Survey participants were asked to identify the person who they asked for help from most often who did not live in the home. They were then asked whether or not that person lived in their neighborhood or elsewhere. Primary social supports within the neighborhood were recoded as “1” and those located outside the neighborhood were recoded as a “0.”

Additional control variables included parent gender (male coded as “1”), parent age, and employment status. Respondents who reported part or full time employment were recoded as employed. Those reporting not being employed, a stay at home parent, or retired were coded as not employed.

Data Analysis Procedures

This study first assessed the factors related to the natural logarithm for size of activity spaces for parents using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression procedures. Negative binomial models were used to assess the how activity spaces and other neighborhood social processes were related to frequency of punitive and non-punitive parenting behaviors. Negative binomial procedures were chosen because the outcome variables represented counts and were overdispersed (i.e., variance was greater than the mean), meaning Poisson models were not appropriate for these data. Due to the exploratory nature of the study and small sample size, significance was assessed at .10.

Results

We first present the results for the OLS model examining those variables related to a size of a parent's activity space (Table 2). Next we present the results of the relationship between size of activity spaces and neighborhood social processes for the frequency of non-punitive parenting behaviors (Table 3) while Table 4 shows the same for punitive parenting behaviors.

Table 2. OLS Regression of Demographic, Family, Social Characteristics on Logged Size of Activity Space (n = 39).

| Variable Name | B | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.064 | 0.485 | |

| Male | 1.081 | 0.485 | 0.032 |

| Employed | -0.006 | 0.434 | |

| More than 1 child under 18 in household | -0.635 | 0.565 | |

| Primary social support lives within neighborhood | 0.883 | 0.430 | 0.048 |

| Participation in any local neighborhood, social, or church group | -0.473 | 0.451 |

Table 3. Negative Binomial Model of Activity Space Size, Neighborhood Social Processes, and Non-Punitive Parenting.

| Reward (n = 38) | Monitoring (n = 39) | Ignore Misbehavior (n = 40) | Explain/Teach (n =39) | Diversion (n = 40) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Name | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Intercept | -1.220 | 3.472 | 0.828 | 3.572† | -0.878 | 4.066 | 1.382 | 4.144 | 5.108 | 4.311 |

| Male | -0.284 | 0.616 | 1.254 | 0.715 | 0.735 | 0.702 | -0.326 | 0.643 | 0.412 | 0.771 |

| Parent Age | 0.002 | 0.050 | -0.057 | 0.053 | -0.085 | 0.064 | -0.011 | 0.046 | -0.154 | 0.069* |

| Activity Space Size (ln) | -0.049 | 0.144 | -0.158 | 0.169 | -0.552 | 0.200** | 0.007 | 0.135 | -0.323 | 0.198 |

| Social Support | 1.882 | 0.538*** | 2.034 | 0.570*** | 2.295 | 0.878** | 1.313 | 0.643* | 1.493 | 0.610* |

| Reciprocated Exchange | 0.095 | 0.302 | 0.880 | 0.364* | 0.495 | 0.362 | 0.376 | 0.285 | 1.089 | 0.327** |

| Informal Social Control | -0.149 | 0.324 | -0.393 | 0.471 | 0.576 | 0.409 | -0.459 | 0.435 | -1.150 | 0.560* |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Table 4. Negative Binomial Model of Activity Space Size, Neighborhood Social Processes, and Punitive Parenting.

| Psychological Aggression (n = 40) | Penalty Tasks (n = 40) | Deprivation of Privileges (n = 40) | Corporal Punishment (n = 40) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Name | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Intercept | 0.638 | 4.189 | 7.510 | 4.528† | -4.698 | 3.935 | -26.336 | 9.551** |

| Male | -0.439 | 0.837 | -0.400 | 0.832 | -0.028 | 0.756 | -0.850 | 1.305 |

| Parent Age | 0.046 | 0.062 | -0.079 | 0.058 | 0.003 | 0.063 | 0.157 | 0.104 |

| Activity Space Size (ln) | -0.096 | 0.140 | -0.425 | 0.138** | -0.322 | 0.174† | -0.672 | 0.267* |

| Social Support | 1.152 | 0.570* | 0.372 | 0.662 | 2.816 | 0.668*** | 6.500 | 1.718*** |

| Reciprocated Exchange | 1.649 | 0.454*** | 0.548 | 0.432 | 0.427 | 0.419 | 1.123 | 0.622† |

| Informal Social Control | 0.161 | 0.573 | -0.069 | 0.674 | 0.911 | 0.485† | 1.890 | 0.876* |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Size of activity space

Bivariate results in Table 1 show that the size of activity space (in square miles, logged) is related to gender and presence of a primary support living within the neighborhood. In the multivariate model, men who are primary caregivers report having larger activity spaces than do women. Parents who report having their primary social support within the neighborhood also had larger activity spaces than those who do not have a local primary support. Employment outside the home, having more than one child under the age of 18, and participating in any local community organizations were not related to the size of activity spaces for parents. A visual depiction of differences in activity spaces can be found in Figures 1 and 2. Respondent 307 is a 43 year old married White female with a graduate degree, reporting her parenting behavior for her 8 year old. Respondent 244 is a 42 year old married White female with a graduate degree, reporting her parenting behavior for her 10 year old. Both women were employed outside of the home. The main difference between these two respondents was that Respondent 307 reported that her primary source of support was located within her neighborhood while Respondent 244 identified her primary social support as being outside her neighborhood area. Respondent 127 is an employed, married, White male, 46 years of age who has a graduate degree and is reporting parenting behavior for his 8 year old. His primary social support is located within the neighborhood. Respondent 518 is a non-White, 49 year old, married, employed male, with a graduate degree reporting on how he parents his 9 year old. This respondent's primary support lives outside his neighborhood.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Individual, Family, Parenting, and Social Characteristics of Study Sample.

| Variable Name | % or x̄ (sd) | n | Activity Space Size, logged |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Activity Space (in square miles, logged) | 0.49 (1.37) | 40 | |

| Dimensions of Discipline (number of times per year) | |||

| Reward | 405.75 (425.23) | 40 | |

| Monitoring | 252.39 (337.97) | 41 | |

| Ignore Misbehavior | 17.57 (43.01) | 42 | |

| Explain/Teach | 370.78 (395.78) | 41 | |

| Diversion | 75.27 (150.75) | 41 | |

| Psychological Aggression | 57.29 (137.91) | 42 | |

| Penalty Tasks | 102.19 (178.83) | 42 | |

| Deprivation of Privileges | 52.81 (129.28) | 42 | |

| Corporal Punishment | 3.24 (15.44) | 42 | |

| Child Age (in years) | 7.76 (2.93) | 42 | -0.02 |

| Parent Age (in years) | 43.34 (5.72) | 42 | -0.12 |

| Parent Gender* | |||

| Male | 28.6 | 12 | 1.16 |

| Female | 71.4 | 30 | 0.21 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Latino | 9.5 | 4 | 0.36 |

| White | 69.0 | 29 | 0.62 |

| Asian | 14.3 | 6 | 0.02 |

| Other | 7.2 | 3 | 0.49 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 52.4 | 22 | 0.27 |

| Not employed, including stay at home parents | 47.8 | 20 | 0.69 |

| Education | |||

| Less than college degree | 23.8 | 10 | 0.65 |

| Four year college degree | 38.1 | 16 | 0.49 |

| Graduate degree | 38.1 | 16 | 0.39 |

| Income | |||

| Less than or equal to $100,000 | 35.2 | 13 | 0.50 |

| $101,000 - $150,000 | 32.4 | 12 | 0.09 |

| Greater than $150,000 | 32.4 | 12 | 1.16 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 90.5 | 38 | 0.41 |

| Separated, divorced, or never married | 9.5 | 4 | 1.27 |

| Number of children less than 18 | 2.14 (0.78) | 42 | -0.09 |

| Primary Social Support* | |||

| Within neighborhood | 59.5 | 25 | 0.82 |

| Outside neighborhood | 40.5 | 17 | -0.05 |

| Social Support | 3.72 (0.30) | 42 | 0.19 |

| Reciprocated Exchange | 3.10 (0.62) | 42 | -0.09 |

| Informal Social Control | 4.35 (0.57) | 42 | -0.06 |

| Participation in neighborhood, social or church groups | |||

| Yes | 71.4 | 30 | 0.41 |

| No | 28.6 | 12 | 0.69 |

p < .05 (logged size of activity space and covariates)

Values for social support, reciprocated exchange, and informal social control refer to averages on the scale where higher values represent higher levels of each of the variables.

Non-punitive Parenting

In Table 3, size of activity space was negatively related to frequency of ignoring misbehavior, but was not related to any of the other non-punitive parenting behaviors. Having higher levels of social support was related to more frequent non-punitive parenting for all five of the behaviors assessed (use of rewards, monitoring, ignoring misbehavior, explaining/teaching, and diversion). Older parents and those reporting higher levels of informal social control used diversion tactics less frequently. Higher levels of reciprocated exchange were related to more frequent use of diversion and monitoring.

Punitive Parenting

In contrast to non-punitive parenting, size of activity space was related to frequency for three of four punitive parenting behaviors. Parents with larger activity spaces used penalty tasks, deprivation of privileges, and corporal punishment less frequently. Paradoxically, higher levels of social support were related to more frequent use of psychological aggression, deprivation of privileges, and corporal punishment. Higher levels of reciprocated exchange was related to more frequent use of psychological aggression and corporal punishment. Informal social control was positively related to frequency of deprivation of privileges and corporal punishment.

Discussion

Here we present findings from an exploratory study examining correlates of activity spaces for parents and how these activity spaces are related to use of punitive and non-punitive parenting behaviors. We found partial support for our first hypothesis: men did have a larger activity space but employment status was not related to size of activity space in our study. Those with a local (within neighborhood) primary support member had larger activity spaces. Having a local primary support provides parents with needed child care or respite that allow them to conduct activities or errands that take longer or are further from home. Parents without this support would have to take children on these errands or leave older children home alone, curtailing longer trips that are further away from home. Sastry and colleagues (2002) found that having friends or family members within the neighborhood was related to a perception of a larger neighborhood area which may make people feel more comfortable traversing across larger areas to conduct daily activities and access services or resources. Although Jones & Pebley (2014) found that having any friends in the neighborhood was related to a smaller activity space (not larger activity space like found here), our study was different in that we asked about the location of a primary support outside the home. Unlike previous work, we did not find participation in organizations to be related to the size of activity space (Sastry et al., 2002). We also did not find employment to be related to size of activity space. Given that this is a sample of a fairly homogenous middle to upper middle class area, these parents are better able to live closer to where they work and/or design their lives to be closer to home. As these findings are among the first to examine activity spaces specifically for parents, more work should be conducted that attempts to understand the exact mechanisms behind these findings.

Our second hypothesis was also partially confirmed. With regards to parenting behaviors, our preliminary assessment suggests that the size of a parent's activity space is negatively related to use of punitive parenting, but generally not related to non-punitive parenting behaviors. These findings for punitive parenting might be tapping into social isolation of parents, a risk factor for maladaptive parenting (Thompson, 2014). This isolation could lead to frustration and harsh parenting practices. Parents who have bigger activity spaces are also likely to come into contact with people who would report or not sanction these types of harsh parenting.

Interpreting our parenting findings within a contagion model, parents' concerns for this censure by others, particularly when traversing larger geographic areas, may make parents more mindful of using non-punitive behaviors with their children. (We should note that in general, non-punitive parenting behaviors occurred much more frequently on average than punitive parenting.) Thus the influence of weak ties through more contacts for parents provide opportunities for exposure to different parenting styles or make parents modify their own parenting to conform to practices that are less likely to receive censure. This interpretation is supporting by findings of a social network intervention (e.g., social skills training, personal networking) designed to reduce child neglect which found parents used corporal punishment less often than a control group that did not receive the intervention (Gaudin, Wodarski, Arkinson, & Avery, 1990). In some respects education and awareness campaigns are designed to take advantage to these contacts between individuals to encourage bystanders to report abusive or neglectful parenting practices. The extent to which this social contagion occurs creates an environment where parents who are participating in activities or running errands in a variety of geographic areas are likely to come into contact with someone who is willing to acknowledge and censure punitive and harsh parenting practices. This study furthers our understanding of how the size of a parent's activity spaces is related to punitive parenting by identifying a geographic component which could enhance the transmission of positive parenting behaviors.

Our study found that higher levels of social support was related to more frequent use of all almost all types of punitive and non-punitive parenting behaviors (the lone exception being use of penalty tasks.) This finding was somewhat unexpected as social support is considered to be protective of maladaptive parenting, particularly as it relates to abusive and neglectful parenting (Thompson, 2014). One interpretation is that parents with high levels of social support use all types of parenting behaviors more often, resulting in the relationship seen here. In other words, more frequent use of punitive and non-punitive parenting behaviors could be indicative of a child who needs a lot of parenting intervention, so parents try all the tools at their disposal to address behavior problems. These parents might also seek out social support because of the stress associated with a child exhibiting these needs. As another interpretation, if punitive parenting behaviors are not censured by social supports, then these behaviors might occur more frequently (Emery et al., 2014). Recent work has found that one type of social support, social companionship (defined as having a large number of people to do social activities with), was related to more frequent use of physical abuse (Freisthler et al., 2014). The small sample size of this study precluded us from examining different types of social support.

Neighborhood social processes were also related to use of punitive and non-punitive parenting practices. Higher levels of reciprocated exchange were related to greater use of monitoring and diversion, but also more frequent use of psychological aggression and corporal punishment. The findings related to monitoring and diversion suggest that having reciprocating relationships with others in the neighborhood provides access to individuals who can assist with helping parents keep track of children's behaviors or providing the parent with ideas of other activities when children are misbehaving. On the other hand, this level of reciprocation might make parents more keenly aware of when their children are acting up, compelling them to use more punitive measures (such as corporal punishment) to ensure this behavior does not occur again in front of their neighbors. A similar relationship is seen with social control. If neighbors are willing to intervene when they see bad behavior of children and youth in the neighborhood, parents might be more willing to deprive a child of privileges or use corporal punishment when they act up, in order to prevent future behavior from occurring. The findings related to informal social control are in contrast to recent findings related to child maltreatment, where higher levels of social control were related to less frequent use of abusive parenting (Guterman et al., 2009). While informal social control may increase use of punitive parenting, but not quite abusive parenting, the same social control could result in neighbors reporting abusive parenting. Further, as this study was conducted within the same neighborhood, we are able to better identify individual differences in perceptions of informal social control and reciprocated exchange than those due to structural neighborhood processes. The exact role of neighborhood social process on parenting should be studied in larger samples with a variety of parenting measures to ascertain how reciprocated exchange and informal social control can be leveraged to increase positive parenting practices.

Limitations

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, several limitations do not permit generalizability. The small sample size of parents in the dataset meant that the number of variables that could be included in any analysis was limited. Further, we were not able to test any interactions between activity spaces and neighborhood social processes. Our sample was largely comprised of white middle class residents living in one neighborhood in Los Angeles. Los Angeles is known for its vast urban sprawl so activity spaces of individuals living in this city may be significantly different than others living in other urban, suburban, or rural contexts. This study needs to be replicated with larger sample sizes and in different geographic locales to examine whether or not these findings are consistent across other locations, among different populations, and using alternative measurement techniques. Reliability estimates for some parenting subtypes were quite low. This was likely due to small number of items making up that subtype and the small sample size used here.

Our preliminary assessment of activity spaces were based on “as the crow flies” distances where we created straight lines from one location to another. The resulting polygon gave us an assessment of how large or how small the activity space was, but did not provide any information on additional risks that might occur when you use roadway networks to assess these activity spaces. While roadway networks might provide a better estimation of where people spend time and how they get there, it also requires more resources to ascertain exact routes and geocode those to create roadway based activity spaces. In general, such studies use GPS tracking devices to monitor a person's movement for several days to determine the full extent of geospatial contexts within which individuals move. Our small study did not have the resources to construct activity spaces in that manner. A different measurement of activity spaces could result in different findings and remains a ripe area for future study. Given these limitations, this study should be viewed as preliminarily and cautiously as one of the first to examine the role of activity spaces on parenting behaviors, but much more research that seeks to replicate and extend this work among larger more diverse populations is needed.

Practice Implications and Conclusions

Despite these limitations, several practical, if limited, implications would be to assess where parents spend time and that location's distance from his or her home as a measure of social isolation. A sense of this would allow social workers who work with families to identify specific activities that would get vulnerable parents outside their own home and participating in activities that could result in less use of punitive or harsh parenting. This is particularly salient for young or new parents who are likely to feel overwhelmed initially. Connecting to a group or groups that encourage these folks to get out of the house more often and into the community could reduce the risk of using punitive parenting practices. We can also modify successful prevention efforts to add an explicit place-based or activity space component. For example, nurse family partnership programs have home visitors that visit new parents in their home to provide them with support and information. If home visitors do something with the new parent outside of the home (e.g., take the mother and child to a local park or another mother-child friendly venue), it might increase their activity space and exposure to child-friendly venues. This would also serve to increase those contact rates that might help prevent maladaptive parenting.

The list to where this line of inquiry could expand is quite long. In addition to building studies that fix the deficits of this study (low sample size, middle class families), future work can determine whether activity spaces differ for subgroups of people and how that might relate to risk for maladaptive parenting. For example, if wealthier white families are segregated into smaller areas, smaller activity spaces could buffer them from harm if all the resources they need are local. However, for low income minority segregated residents, small activity spaces may indicate a level of isolation that negatively affects parenting abilities. Thus depending on the availability of resources, the size of the activity space might not matter. For vulnerable families, understanding where they spend time can provide information on where social services should be placed in order to ensure families can easily access them. Understanding more about the social interactions (e.g., size of social networks, frequency of contacts) that occur within these activity spaces is an important consideration in determining whether it is merely size of activity space or the social relationships within them that affect parenting behaviors. Finally, can activity spaces be easily modified to place at-risk parents in contact with “better” parents? If so, these contacts could model and encourage less punitive parenting practices than would have been used. The exploratory nature of this study had some intriguing findings, but better-powered studies with more diverse samples would provide us with better direction of how activity spaces can be modified to reduce maladaptive parenting.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This project was supported by grant number P60-AA-006282 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and a faculty fellowship from the John Randolph and Dora Haynes Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Bridget Freisthler, Department of Social Welfare, Luskin School of Public Affairs, University of California, Los Angeles, 3250 Public Affairs Building, Box 951656, Los Angeles, CA 90095

Crystal A. Thomas, Department of Social Welfare, Luskin School of Public Affairs, University of California, Los Angeles, 3250 Public Affairs Building, Box 951656, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Susanna R. Curry, Department of Social Welfare, Luskin School of Public Affairs, University of California, Los Angeles, 3250 Public Affairs Building, Box 951656, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Jennifer Price Wolf, Prevention Research Center Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation 180 Grand Avenue, Suite 1200 Oakland, CA 94612-3749

References

- Brauer F, Castillo-Chávez C. Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology. NY: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Soller B. Moving beyond neighborhood: Activity spaces and ecological networks as contexts for youth development. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research. 2014;16(1):165–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Jarrett RL. In the mix, yet on the margins: The place of families in urban neighborhood and child development research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1114–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Chung HL, Steinberg L. Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance, and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):319–331. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarack T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research, and application. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Coiera E. Social networks, social media, and social diseases. BMJ. 2013;346:f3007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coohey C. Social networks, informal child care, and inadequate supervision by mothers. Child Welfare. 2007;68(6):53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C, Crampton D, Irwin M, Spilbury J, Korbin J. How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:1117–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C, Korbin J, Su M. Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: a multi-level study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(11):1019–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford T, Jilcott Pitts S, McGuirt J, Keyserling T, Ammerman A. Conceptualizing and comparing neighborhood and activity space measures for food environment research. Health and Place. 2014;30:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar J, Jones DJ, Sterrett E. Examining Parenting in the Neighborhood Context: A Review. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9826-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Forehand R. The relation of social capital to child psychosocial adjustment difficulties: The role of positive parenting and neighborhood dangerousness. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25(1):11–23. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed AM, Scarborough P, Seemann L, Galea S. Social network analysis and agent-based modeling in social epidemiology. Epidemiologic Perspectives & Innovations. 2012;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery C, Nguyen H, Kim J. Understanding child maltreatment in Hanoi: Intimate partner violence, low self-control, and social and child care support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29:1228–1257. doi: 10.1177/0886260513506276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ. Where the individual meets the ecological: A study of parent drinking patterns, alcohol outlets and child physical abuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;27(6):993–1000. doi: 10.1111/acer.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Holmes MR, Price Wolf J. The dark side of social support: Understanding the role of social support, drinking behaviors and alcohol outlets for child physical abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38:1106–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudin JM, Wodarski JS, Arkinson MK, Avery LS. Remedying child neglect: Effectiveness of social network interventions. Journal of Applied Social Sciences. 1990;15(1):97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Taylor CA, Rathouz P. Parental perceptions of neighborhood processes, stress, personal control, and risk for physical child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33(12):897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Affective and cognitive processes in moral internalization. In: Higgins ET, Ruble DN, Hartup WW, editors. Social cognition and social development: A sociocultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1983. pp. 236–274. [Google Scholar]

- Inagami S, Cohen DA, Finch BK. Non-residential neighborhood exposures suppress neighborhood effects on self-rated health. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1779–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Pebley AR. Redefining neighborhoods using common destinations: Social characteristics of activity spaces and home Census tracts compared. Demography. 2014;51:727–752. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamruzzaman M, Hine J. Analysis of rural activity spaces and transport disadvantage using a multi-method approach. Transport Policy. 2012;19:105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack WO, McKendrick AG. A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 1927;115:700–721. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1927.0118.JSTOR94815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limber SP, Hashima PY. The social context: What comes naturally in child protection. In: Melton GB, Thompson RA, Small MA, editors. Toward a child-centered, neighborhood-based child protection system: A report of the consortium on children, families, and the law. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA. Spatial polygamy and the heterogeneity of place: Studying people and place via geocentric methods. In: Burton LM, Kemp SP, Leung M, Matthews SA, Takeuchi DT, editors. Communities, neighborhoods, and health: Expanding the boundaries of place. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Brennan RT, Holton JK, Earls F. A multilevel study of neighborhoods and parent-to-child physical aggression: Results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:84–97. doi: 10.1177/1077559502250822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noach E. Are rural women mobility deprived? A case study from Scotland. Sociologia Ruralis. 2011;51(11):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Oates RK, Davis AA, Ryan MG, Stewart LF. Risk factors associated with child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1979;3:547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Parker K, Wang W. Modern Parenthood: Roles of Moms and Dads Converge as they Balance Work and Family. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F. Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:633–660. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry N, Pebley AR, Zonta M. CCPRWorking Paper 033-04. Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research, University of California–Los Angeles; 2002. Neighborhood definitions and the spatial dimension of daily life in Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Fauchier A. Manual for the Dimensions of Discipline Inventory (DDI) Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire; 2011. http://pubpages.unh.edu/∼mas2/ [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Social support and child protection: Lessons learned and learning. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen KG, Fauchier A, Straus MA. Assessing dimensions of parental discipline. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment. 2012;34(2):216–231. doi:org/10.1007/s10862-012-9278-5. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple EE, Richey CA. Crossing the line from physical discipline to child abuse: How much is too much? Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(5):431–444. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00004-5. doi:org/10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106(1):3. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. doi:org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolock I, Magura S. Parental substance abuse as a predictor of child maltreatment re-reports. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]