Abstract

Emerging research suggests significant positive associations between bullying and substance use behaviors. However, these studies typically focused either on the link between substance use and bullying perpetration or victimization, and few have conceptualized bullying perpetration and/or victimization as mediators. In this study, we simultaneously tested past bullying perpetration and victimization as mediational pathways from retrospective report of parenting styles and global self-esteem to current depressive symptoms, alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Data were collected from a college sample of 419 drinkers. Mediation effects were conducted using a bias-corrected bootstrap technique in structural equation modeling. Two-path mediation analyses indicated that mother and father authoritativeness were protective against bully victimization and depression through higher self-esteem. Conversely, having a permissive or authoritarian mother was positively linked to bullying perpetration, which in turn was associated with increased alcohol use, and to a lesser degree, more alcohol-related problems. Mother authoritarianism was associated with alcohol-related problems through depressive symptoms. Three-path mediation analyses suggested a trend in which individuals with higher self-esteem were less likely to report alcohol-related problems through lower levels of bullying victimization and depression. Results suggested that bullying perpetration and victimization may respectively serve as externalizing and internalizing pathways through which parenting styles and self-esteem are linked to depression and alcohol-related outcomes. The present study identified multiple modifiable precursors of, and mediational pathways to, alcohol-related problems which could guide the development and implementation of prevention programs targeting problematic alcohol use.

Keywords: Parenting, Self-esteem, Bullying, Depression, Alcohol, Mediation

The belongingness hypothesis (Baumiester & Leary, 1995) posits that a lack of positive social attachments may lead to adverse effects on an individual’s well-being, such as using alcohol to dampen the effects of rejection by parents or peers (Marlatt, 1987; Sayette, 1993; Sher, 1987). Consistent with this hypothesis, interpersonal rejection and social withdrawal in childhood have been proposed as developmental precursors of subsequent alcohol use disorders (Hussong, Jones, Stein, Baucom, & Boeding, 2011). Prospective research indicated that childhood bullying experiences elevated risks for alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use in young adulthood (Kim, Catalano, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2011; Niemelä et al., 2011). Generally, individuals can experience bullying as the perpetrator and/or the victim: bullying perpetration refers to intentional and repeated aggressive behavior intended to harm another with words or deeds (Olweus, 1993; Wang, Iannotti, & Luk, 2012), whereas bully victimization refers to being the victim of intentional social isolation, verbal or physical aggression (Olweus, 1993; Wang, Iannotti, Luk, & Nansel, 2010). The overarching goal of this study was to examine whether bullying perpetration and victimization respectively acted as externalizing and internalizing pathways from retrospective parenting styles to current alcohol use and alcohol-related problems.

Parenting Styles and Involvement in Bullying Behaviors

Impaired social adjustments may be traced back to early parent-child attachments, and bullying perpetration and victimization may both reflect dissatisfying interpersonal bonds early in development (Lereya, Samara, & Wolke, 2013). For example, Georgiou and Stavrinides (2013) found that parent-child conflict was positively associated with bullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents. Compared to victims of bullying, children who were not bullied reported a greater level of parenting that supports the development of social skills and healthy peer relationships (Healy, Sanders, & Iyer, 2013). In a recent randomized controlled trial of the Resilience Triple P intervention for bullied children, families receiving the intervention (combining facilitative parenting and social skills training for children with parents present for all eight sessions) showed greater improvements than families in the assessment control condition on multiple outcome measures, including overt aggression towards peers, overt victimization, internalizing feelings, and depressive symptoms (Healy & Sanders, 2015). This suggests that coaching parents to be more effective and facilitating in the way they interact with their children can be a promising avenue to intervene with bullying behaviors.

According to Baumrind’s (1971) classic parenting paradigm, parent-child interactions can broadly be described in three prototypical styles: authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive. Authoritative parenting is characterized by clear and reasonable instructions with high parental warmth; it has been linked to lower levels of bullying perpetration and victimization in some studies (Åman-Back & Björkqvist, 2007; Baldry & Farrington, 2005) but not in other studies (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2004; Dehue, Bolman, Vollink, & Pouwelse, 2012; Hay & Meldrum, 2010). Authoritarian parenting is characterized by forceful control of a child without providing reason or parental warmth, and it has been linked to higher levels of bullying and the co-occurrence of bullying and victimization (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2004; Baldry & Farrington, 1998). Permissive parenting is characterized by high parental warmth and limited structure and few demands, and it has rarely been examined in relation to bullying perpetration and victimization. In one study, permissive parenting was related to greater bullying perpetration but was unrelated to bullying victimization (Dehue et al., 2012).

Bullying Perpetration as an Externalizing Pathway to Alcohol Use and Related Problems

Etiological models of substance use suggest that early externalizing behaviors are significant predictors of later substance use behaviors (Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991; Tarter et al., 1999), in which behavioral undercontrol-disinhibition is conceptualized as the core risk phenotype (Zucker, Heitzeg, & Nigg, 2011). Empirical research suggested a positive association between bullying perpetration and externalizing problems, including carrying weapons and using substances (Luk, Wang, Simons-Morton, 2012; Wang et al., 2012). In a large-scale school-based survey, Radliff, Wheaton, Robinson and Morris (2012) found that middle school students who experienced bullying perpetration were at elevated risks for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in the past 30 days.

The direct association between bullying perpetration and substance use has been replicated in both cross-sectional (Carlyle & Steinman, 2007; Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpelä, Rantanen, & Rimpelä, 2000; Nansel et al., 2001) and longitudinal studies (Kim et al., 2011; Niemelä et al., 2011), suggesting bullying perpetration may represent an externalizing pathway to substance use (Peleg-Oren, Cardenas, Comerford, & Galea, 2012). Despite these studies, no prior research that we are aware of has tested bullying perpetration as a mediator of retrospective parenting styles and current alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. In testing the externalizing pathway, we sought to identify the specific type(s) of parenting style that would be indirectly linked to alcohol involvement through bullying perpetration.

Bullying Victimization as an Internalizing Pathway: Roles of Self-Esteem and Depression

Prior research suggested that authoritative parenting style is associated with higher self-esteem (Hamon & Schrodt, 2012; Steinberg, 2011), whereas authoritarian and permissive parenting styles are linked to lower self-esteem (Heaven & Ciarrochi, 2008; Milevsky, Schlechter, Netter, & Keehn, 2007). Moreover, self-esteem is a protective factor against bully victimization (Guerra, Williams, & Sadek, 2011; Skues, Cunningham, & Pokharel, 2005). One possible explanation is that children with low self-esteem may adopt a more passive response style to victimization from bullying (Sharp, 1996). Taken together, parenting styles may be indirectly associated with bullying victimization through self-esteem.

Emerging evidence also suggests a positive association between bullying victimization and substance use (McGee, Valentine, Schulte, & Brown, 2011; Tharp-Taylor, Haviland, & D'Amico, 2009; Wormington, Anderson, Tomlinson, & Brown, 2013), which may be mediated by internalizing symptoms such as depression (Luk, Wang, & Simons-Morton, 2010). Indeed, victims of bullying are more vulnerable to social alienation, negative mood, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation than non-victims (Cassidy, 2009; Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd, & Marttunen, 2010; Menesini, Modena, & Tani, 2009). Moreover, multiple longitudinal studies indicated depressive symptoms were associated with substance use in a bi-directional manner (Needham, 2007; Sihvola, Rose, Dick, Pulkkinen, Marttunen, & Kaprio, 2008; Wu et al., 2008). Presumably, some adolescents who experience bullying victimization may use alcohol or other substances to cope with their negative emotions (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2003). In testing the internalizing pathway, we first tested bullying victimization as the sole mediator in the internalizing pathway, and then added self-esteem and depression as additional mediators in the full model.

The Scope of the Present Study

Bullying and substance use are significant public health problems that are associated with poorer psychological and social adjustment (Nansel et al., 2001; Young et al., 2002). The goal of this study was to simultaneously model bullying perpetration and victimization as potential mediational pathways from retrospective parenting styles and global self-esteem to current depression, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. We hypothesized that authoritative parenting styles would promote self-esteem and protect against bullying, depression, alcohol-related outcomes, whereas authoritarian and permissive parenting styles would have detrimental effects of self-esteem, bullying, depression, and alcohol-related outcomes. Moreover, we expected that bullying perpetration and victimization would mediate some of the links between parenting styles and alcohol-related outcomes.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from 646 university students (330 women, 316 men) who received course credit for their participation. We restricted our final sample to only drinkers of alcoholic beverages yielding 419 participants (196 women, 223 men). The sample was 53% male, with an average age of 20.19 years (SD = 3.02). The sample was 58.2% Caucasian, 17.3% Hispanic, 11.1% Asian, and 8.8% African American and 4.6% reported “other” race/ethnicity.

Procedure

Data collection occurred at two major southwestern universities with full Institutional Review Board approval. All data were collected using paper-and-pencil questionnaires, with the use of an anonymous drop box to ensure participant anonymity.

Measures

Model 1: Parenting Styles, Bullying Experiences, Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Problems

Parenting Styles

The Parental Authority Questionnaire (Buri, 1989; Buri, 1991) is a 60-item retrospective measure, 30 per parent, based on Baumrind’s (1971) prototypes of permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian styles of decision making within a family. A sample item for the 10-item authoritativeness scale was: “My (mother/father) always encouraged verbal give-and-take whenever I have felt that the family rules and restrictions were unreasonable.” A sample item for the 10-item authoritarianism scale was: “My (mother/father) felt that wise parents should teach their children early just who is boss in the family”. A sample item for the 10-item permissive scale was: “My (mother/father) has always felt that what children need is to be free to make up their own minds to do what they want to do”. Responses for the Parental Authority Questionnaire were 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=unsure, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alphas in this sample were as follows: mother permissive 0.77, father permissive 0.80, mother authoritarian 0.85, father authoritarian 0.89, mother authoritative .84, and father authoritative 0.89.

Bullying Perpetration and Victimization

Participants were asked to retrospectively report on bullying during elementary school on an adapted version of the well-validated Revised Olweus Bullying/Victim Questionnaire (Kyriakides, Kaloyirou, & Lindsay, 2006; Lee & Cornell, 2010; van de Vijer & Hambleton, 1996; Vessey, Strout, Difazio, & Walter, 2014). Retrospective report of past bullying behaviors is common in the literature (e.g., Hoetger, Hazen, & Brank, 2015; Holt et al., 2014; Hunter, Mora-Merchan, & Ortega, 2004; Schäfer et al. 2004), which includes retrospective report of childhood and adolescent bullying experiences in adulthood (e.g., Frizzo, Bisol, & Lara, 2013; Staubli & Killias, 2011). Prior research indicated considerable stability of bullying experiences over time (Chapell, Hasselman, Kitchin, Lomon, Maclver, & Sarullo, 2006), and retrospective recall of specific types of bullying was rather consistent across time (Rivers, 2001). This bullying questionnaire has 16 items (8 questions on perpetration and 8 questions on victimization). Sample items for the perpetration scale included: “How many times did you take money or other things from them or damaged their belongings?” and “How many times did you spread false rumors about them and tried to make others dislike them?” Sample items for the victimization scale included: “How many times were you hit, kicked, pushed, shoved around, or locked indoors?” and “How many times were you called mean names, made fun of, or teased in a hurtful way?” We used an adapted 8-point likert scale for responses, with 1=never, 2=once a year, 3=once every 6 months, 4=once a month, 5=2 or 3 times a month, 6=once a week, 7=2 to 3 times a week, 8=daily or nearly daily. The Cronbach’s alphas for both bullying perpetration and victimization were 0.86.

Alcohol Use

The alcohol quantity and frequency items were combined into a single quantity/frequency scale by converting the frequency levels into equivalent occasions per month which ranged from 1=0.5 times per month to 7=28 times per month, and the quantity levels into equivalent grams of alcohol which ranged from 1=10 grams a month to 7=70 grams a month. These values were then multiplied, and the distribution of scores was converted through a log10 transformation (Wood, Nagoshi, & Dennis, 1992).

Alcohol-Related Problems

These items came from the Problem with Alcohol Use Scale measuring alcohol-related problems related to alcohol abuse or dependence (Rhea, Nagoshi, & Wilson, 1993). The questionnaire has 11 items. Sample items included: “How many times have you felt you drank too much, possibly damaging your mental and/or physical health?” and “How many times have you resented and/or avoided people who commented on your drinking habits?” Responses were assessed on a scale from 0=never to 3=many times. The Cronbach’s alpha for the Problems with Alcohol Use Scale was 0.88.

Model 2: Self-Esteem and Depression as Additional Mediators in the Internalizing Pathway

Self-Esteem

The Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) was administered in its original form to measure global self-esteem. Longitudinal research suggested that global self-esteem is a trait that tends to be stable across the lifespan except at very old ages (Arnold, 1988; Trzesniewski, Donnelian, & Robins, 2003; Wagner, Gertstorf, Hoppmann & Luszcz, 2013). As our sample consisted of college students, we measured self-esteem as a stable personality trait without asking participants to recall on a particular time span in the past. This questionnaire has 10-items, including: “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”, “I take a positive attitude towards myself” and “I certainly feel useless at times” (reverse coded). Participants provided their responses on a 4-point Likert scale with the anchors ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha for self-esteem was 0.90.

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item measure of frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week (Radloff, 1977). It is one of the most widely used depression instruments (Choi, Schalet, Cook, & Cella, 2014), and it has been validated in both late adolescent and young adult samples to assess current depression (Radloff, 1991; Roberts, Andrews, Lewinsohn, & Hops, 1990). Sample items included: “I felt sad,” “I had crying spells,” and “I did not feel like eating.” The Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D was 0.91 for this sample.

Statistical Approach

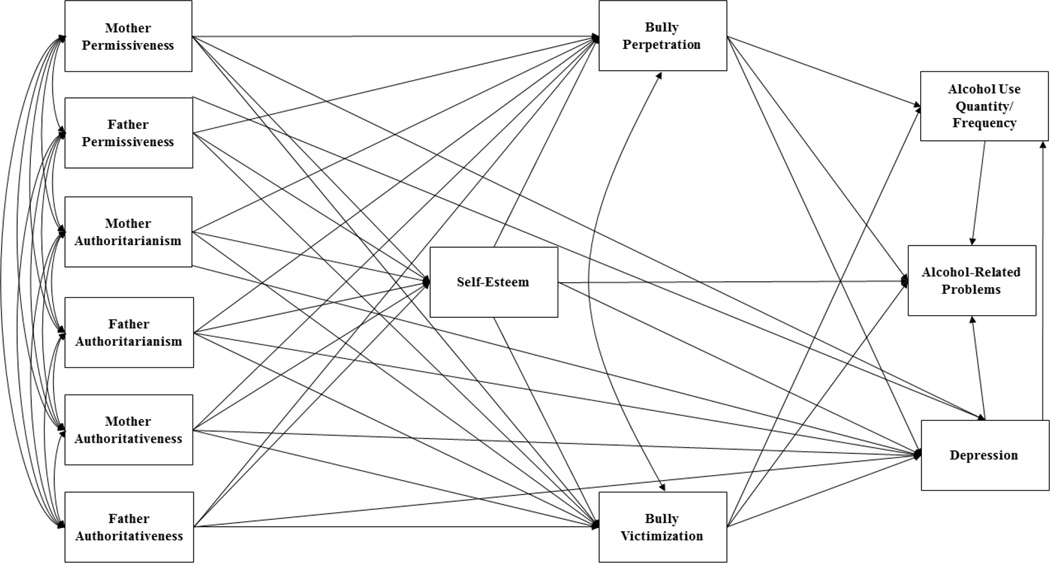

We first obtained descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among key variables of interest. We then tested our conceptual model (Figure 1) in two steps. In Model 1, we only examined the mediating roles of bullying perpetration and victimization on the associations between parenting styles and alcohol involvement. In Model 2, we tested whether self-esteem mediated the link between parenting styles and bullying victimization, and whether depression mediated the link between bullying victimization, alcohol use and alcohol-related problems.

Figure 1.

Bullying perpetration and victimization as externalizing and internalizing mediational pathways: A conceptual model

All analyses were conducted using Mplus version 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014). We evaluated model fit with the chi-squared statistic, RMSEA (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1998), and CFI (Bentler, 1990). Both direct and indirect effects were examined with tests of indirect effects relying on the bias-corrected bootstrap (K=20,000) technique (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993; Manly, 1997), using the model indirect command in Mplus. The bias corrected bootstrap technique was used to address nonnormality that is common in drinking and other drug use data (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). The 95% asymmetric confidence intervals around the estimates were examined to determine if the indirect effects included zero in the interval (Hancock & Liu, 2012; MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, 2007; Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011), with confidence intervals that do not include zero indicating significant indirect effects. Non-significant paths were excluded from both Models 1 and 2.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 1. For the externalizing pathway (without controlling for covariates), parental permissiveness and mother authoritarianism were associated with bullying perpetration. Bullying perpetration was positively associated with both alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. For the internalizing pathway (without controlling for covariates), father authoritative parenting was protective against bullying victimization, whereas father authoritarianism was a risk factor for bullying victimization. Parental authoritativeness was positively associated with self-esteem, whereas mother authoritarian parenting was inversely associated with self-esteem. Self-esteem was protective against bullying victimization, depression, and alcohol-related problems. Depression was not associated with alcohol use but was positively associated alcohol-related problems.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables

| M | SD | Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24.68 | 6.04 | 1 Mother Permissive | 1.00*** | |||||||||||

| 24.79 | 6.70 | 2 Father Permissive | 0.43*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 31.32 | 7.25 | 3 Mother Authoritarian | −0.51*** | −0.06 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 34.25 | 8.41 | 4 Father Authoritarian | −0.19*** | −0.56*** | 0.34*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 35.54 | 6.86 | 5 Mother Authoritative | 0.08 | −0.15** | −0.28*** | 0.08 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 33.26 | 8.17 | 6 Father Authoritative | 0.02* | 0.27*** | −0.10* | −0.38*** | 0.30*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3.24 | 0.63 | 7 Self-Esteem | −0.01* | −0.03 | −0.11* | −0.05 | 0.25*** | 0.23*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 16.76 | 8.95 | 8 Bully Victimization | 0.02* | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.17*** | −0.06 | −0.14** | −0.24*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 12.68 | 6.43 | 9 Bully Perpetration | 0.10* | 0.13** | 0.13** | 0.04 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.35*** | 1.00 | |||

| 34.88 | 11.11 | 10 Depression | −0.03* | 0.00 | 0.21*** | 0.11** | −0.18*** | −0.21*** | −0.60*** | 0.28*** | 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| 1.69 | 0.70 | 11 Alcohol Use | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.20*** | 0.02 | 1.00 | |

| 0.69 | 0.53 | 12 Alcohol Problems | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11* | 0.08 | −0.15* | −0.11* | −0.28*** | 0.21*** | 0.28*** | 0.34*** | 0.40*** | 1.00 |

n = 419 (223 men, 196 women)

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

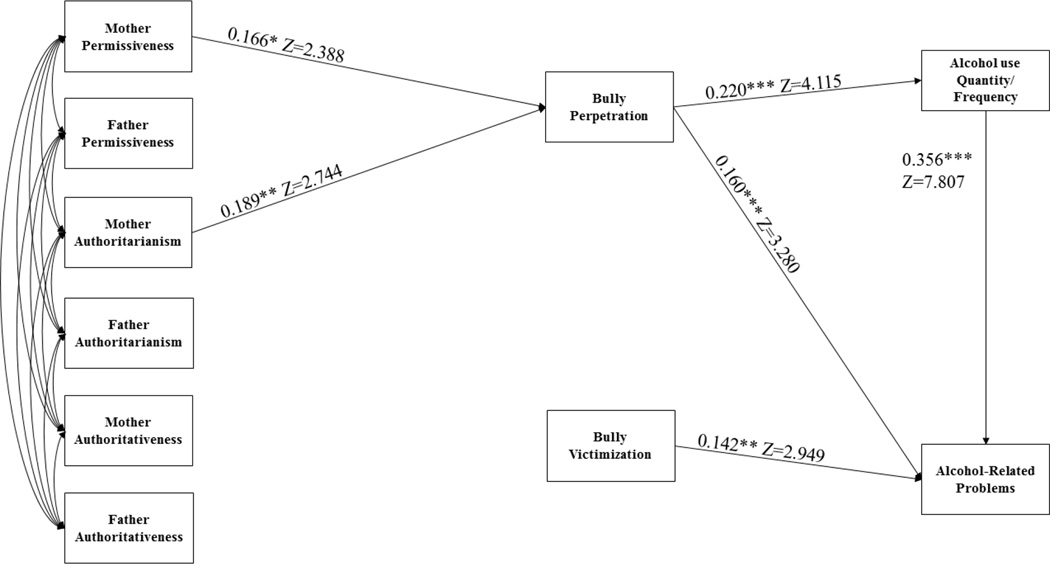

Model 1: Bullying Perpetration and Victimization as Mediational Pathways

The model fit the data well with a χ2 (12df) = 17.411, p = .1348; CFI = 0.970; RMSEA = 0.033, 90% CI (0.000, 0.064). Significant path coefficients are presented in Figure 2. Overall, we found several mediated effects on the externalizing pathway through bullying perpetration, but no mediated effects on the internalizing pathway through bullying victimization.

Figure 2.

Bullying perpetration and victimization as mediators of parenting styles and alcohol use and related problems (Model 1)

Note. Standardized coefficients are shown. All exogenous variables were allowed to correlate freely in the model. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. n = 419; χ2 (12df) = 17.411, p = .1348; CFI = 0.970; RMSEA = 0.033, 90% CI (0.000, 0.064).

Key Two-Path Mediational Links

Higher levels of mother permissiveness were indirectly linked to more alcohol use through more incidences of bullying others [indirect effect = .004, z = 2.098, p = .036; 95% CI (.001, .008)]. Higher levels of mother authoritarianism were indirectly linked to more alcohol use through more incidences of bullying others [indirect effect = .004, z = 2.147, p = .032; 95% CI (.001, .008)]. Higher levels of incidences of bullying others were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more alcohol use [indirect effect = .007, z = 3.196, p =.001; 99% CI (.002, .013)].

Key Three-Path Mediational Links

Higher levels of mother permissiveness were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more incidences of bullying others and more alcohol use [indirect effect = .001, z = 1.971, p =.049; 90% CI (0.000, .002)]. Higher levels of mother authoritarianism were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more incidences of bullying others and more alcohol use [indirect effect = .001, z = 1.991, p =.046; 90% CI (0.000, .002)].

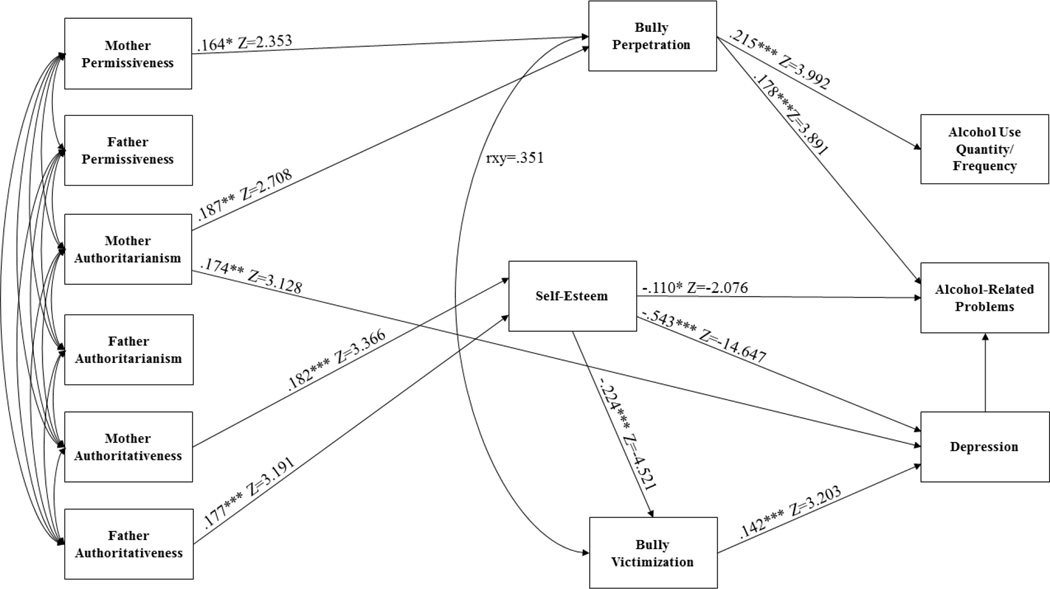

Model 2: Self-Esteem and Depression as Mediational Links in the Internalizaing Pathway

This model provided excellent fit to the data with a χ2 (13df) = 10.138, p = .6826; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.000; 90% CI [0.000, 0.039]. All significant path coefficients are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Testing full model with self-esteem and depression as mediational pathways to alcohol use and related problems (Model 2)

Note. Standardized coefficients are shown. All exogenous variables were allowed to correlate freely in the model. *p <.05, **p <.01, ***p <.001. n=419; χ2 (13df)=10.138, p = .6826; CFI=1.00; RMSEA=0.000, 90% CI (0.000, 0.039).

Key Two-Path Mediational Links

Bullying Victimization

Higher levels of mother authoritativeness were indirectly associated with fewer incidences of being a victim of bullying through higher levels of self-esteem (mediated effect = −0.052; z = −2.406, p = 0.016; 90% CI [−0.097, −0.023]). Similarly, higher levels of father authoritativeness were indirectly associated with fewer instances of being a victim of bullying through increased self-esteem (mediated effect = −0.043; z = −2.403, p = 0.016; 90% CI [−0.078, −0.019]).

Depression

Higher levels of mother authoritativeness were indirectly linked to fewer depressive symptoms through higher levels of self-esteem (mediated effect = − 0.158; z = −2.855, p = 0.004; 90% CI [−0.214, −0.053]). Similarly, higher levels of father authoritativeness were indirectly linked to fewer depressive symptoms through higher levels of self-esteem (mediated effect = −0.130; z = −2.637, p = 0.008; 90% CI [−0.214, −0.053]).

Alcohol Use

Higher levels of mother permissiveness were indirectly linked to increased alcohol use through more instances of bullying others (mediated effect = 0.004; z = 2.013, p = 0.044; 90% CI [0.001, 0.007]). Similarly, higher levels of mother authoritarianism were indirectly linked to increased alcohol use through more instances of bullying others (mediated effect = 0.004; z = 2.063, p = 0.039; 90% CI [0.001, 0.007]).

Alcohol-Related Problems

Similar mediational links through bullying others were found to approach significance (p < 0.10) when we treated alcohol-related problems as the outcome. Specifically, there were trends suggesting that higher levels of mother permissiveness and authoritarianism being indirectly associated with more alcohol-related problems through more incidences of bullying others (mediated effect for mother permissiveness = 0.003; z = 1.742, p = 0.081; 90% CI [0.001, 0.006]; mediated effect for mother authoritarianism = 0.002; z = 1.701, p = 0.089; 90% CI [0.001, 0.005]). There was also a tread suggesting that more instances of being a victim of bullying was associated with more alcohol-related problems through depressive symptoms (mediated effect = 0.002; z = 1.949, p = 0.051; 90% CI [0.001, 0.004]). Finally, higher levels of mother authoritarianism were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through increased depressive symptoms (mediated effect = 0.003; z = 2.561, p = 0.010; 90% CI [0.001, 0.006]).

Key Three-Path Mediational Links

Alcohol-Related Problems

There were two trending three-path mediated effects. First, higher levels of mother authoritarianism were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through more instances of bullying others and alcohol use quantity/frequency (mediated effect = 0.001; z = 1.960, p = 0.050; 90% CI [0.000, 0.002]). Second, higher levels of self-esteem were indirectly linked to fewer alcohol-related problems through fewer instances of bully victimization and fewer depressive symptoms (mediated effect = −0.007; z = −1.854, p = 0.064; 90% CI [−0.015, −0.002]).

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study that simultaneously tested bullying perpetration and victimization as potential externalizing and internalizing pathways to alcohol-related outcomes. We found partial support for our hypothesized model in which parenting styles and self-esteem were tested as precursors of bullying perpetration and victimization, suggesting that other factors may play a significant role in understanding involvement in bullying behaviors. Nonetheless, the current findings indicated specificity in the associations between parenting styles and bullying behaviors. In particular, authoritative parenting style by both mother and father were associated with lower levels of bullying victimization through higher self-esteem, suggesting that positive parenting might be especially relevant to the prevention of bullying victimization. Children who were raised by authoritative parents might have higher levels of self-esteem (Hamon & Schrodt, 2012), which could enable them to adapt a more active rather than passive response style to victimization from bullying (Sharp, 1996). Alternatively, these children might be an unlikely target of bullying in the first place given that they often perform well in academic, psychological, and social domains (Steinberg, 2011).

In contrast, having a permissive or authoritarian mother was linked to increased instances of bullying perpetration. These findings can be understood within the broad framework of the belongingness hypothesis (Baumiester & Leary, 1995) which suggests that a lack of positive social attachments early in life might be linked to poorer social adjustment. Specifically, children who were raised by permissive mothers might be used to testing and pushing limits being paired with no consequences or even reinforcements (Dehue et al., 2012). Eventually, these children might generalize these unacceptable behaviors to target their peers and thus engage in bullying perpetration. According to Baldry and Farrington (1998), authoritarian parents who tend to be punitive and controlling might serve as models of aggressive behaviors, thereby increasing the likelihood of their children to bully their peers. Taken together, mother permissiveness and authoritarianism might both provide a poor socialization context for children and adolescents to develop their social competence, which in turn, might elevate risks for bullying perpetration.

A key finding of this study is that bullying perpetration served as a mediator of the associations between mother permissiveness and authoritarianism and alcohol use (statistically significant effects) as well as alcohol-related problems (trending effects). Etiological theories support the idea that externalizing behaviors may precede the emergence of substance use behaviors across development (Sher et al., 1991; Tarter et al., 1999). Prior empirical research suggested that bullying perpetration is an externalizing behavior that is associated with substance use behaviors (Carlyle & Steinman, 2007; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2000; Nansel et al., 2001). In this study, we identified bullying perpetration as a specific externalizing pathway from poor mother parenting to alcohol use and problems. One plausible explanation is that bullying perpetration is an outward expression of the underlying core deficits in behavioral control-inhibition (Zucker et al., 2011). Alternatively, bullying perpetration may be a unique pathway that is independent of the broader externalizing pathway. Regardless, the implication of this finding is that intervention targeting bullying perpetration may also be one avenue of preventing alcohol use and alcohol-related problems.

We also investigated potential internalizing pathways to alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Our findings are generally consistent with the internalizing pathway model proposed by Hussong and colleagues (2011) which postulates peer rejection and social disengagement in childhood as developmental precursors of subsequent alcohol use disorders. Notably, we found that having an authoritarian mother was associated with more depressive symptoms, which in turn elevated risks for alcohol-related problems. Additionally, we found two trending mediation effects which suggest a potential role of bullying victimization in the internalizing pathway. First, replicating and extending the findings by Luk and colleagues (2010), the present study showed a trend in which bullying victimization was linked not only to a composite scale of substance use (including smoking, alcohol use, and marijuana use), but also to a specific measure of alcohol-related problems through the mediating mechanism of elevated depressive symptoms. Second, we found a three-path mediation in which higher self-esteem was protective against alcohol-related problems through the mediating mechanisms of fewer instances of bullying victimization and fewer depressive symptoms. One explanation for the role of bullying victimization in the internalizing pathway is that individuals who struggle with bullying victimization are more likely to misuse alcohol to cope with their negative emotions (Cooper et al., 1995; Holahan et al., 2003). If this interpretation holds true, then assisting victims of bullying to develop alternative coping methods for peer rejection and depressive symptoms would likely be an important step towards more targeted intervention efforts for problematic alcohol use.

This study has several limitations. First, we utilized retrospective, cross-sectional data to take a first step in testing a developmental model of precursors and outcomes of bullying perpetration and victimization. Although retrospective reporting of bullying is common (e.g., Frizzo et al., 2013; Hoetger et al., 2015; Holt et al., 2014; Hunter et al., 2004; Schäfer et al. 2004), there may be memory errors and biases due to varying degrees of current depression and alcohol involvement. Importantly, the direction of effects tested in this study represents one theoretical framework that ties these variables of interest together and does not capture potential bi-directional effects. For instance, both self-esteem and depression may predict and be affected by bullying victimization. Future studies should extend the current findings by testing bi-directional effects using prospective data. Second, this study utilized a convenience sample of college students, which limits the generalizability of findings. Third, we modeled bullying perpetration and victimization as two correlated variables in the current analysis and did not examine the co-occurrence of both. Finally, three of the mediation effects were trending based on p-values and/or the 90% confidence intervals, and thus should be replicated in future studies.

Despite these limitations, this study adds to existing literature by simultaneously testing bullying perpetration and victimization as externalizing and internalizing pathways to alcohol-related outcomes in the same model. Overall, our findings support the idea that intervention for bullying may present a potentially cost-effective opportunity to prevent problematic alcohol use as it intervenes by targeting the externalizing and internalizing pathways simultaneously. Theoretically, the current findings highlight the importance of studying whether bullying perpetration and victimization are merely behaviors that respectively follow the externalizing and internalizing developmental pathways to problematic alcohol use, or if they represent unique risks that are over-and-above those accounted for by the externalizing and internalizing pathways. Future studies should examine these possibilities and further our understanding of the emergence of alcohol use and disorder across development.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism No. F31 AA020700

Contributor Information

Mr Jeremy W Luk, Email: jwluk@uw.edu, University of Washington, Seattle, United States.

Dr Julie A Patock-Peckham, Email: jpp01@asu.edu, Arizona State University, Tempe, United States.

Ms Mia Medina, Email: mmedin11@asu.edu, Arizona State University, Tempe, United States.

Mr Nathan Terrell, Email: Nathan.Terrell@asu.edu, Arizona State University, Tempe, United States.

Mr Daniel Belton, Email: dbelton@asu.edu, Arizona State University, Tempe, United States.

Dr Kevin M King, Email: kingkm@uw.edu, University of Washington, Seattle, United States.

References

- Ahmed E, Braithwaite V. Bullying and victimization: Cause for concern for both families and schools. Social Psychology of Education. 2004;7:35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Åman-Back S, Björkqvist K. Relationship between home and school adjustment: Children's experiences at ages 10 and 14. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2007;104:965–974. doi: 10.2466/pms.104.3.965-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldry AC, Farrington DP. Parenting influences on bullying and victimization. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 1998;3:237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry A, Farrington DP. Protective factors as moderators of risk factors in adolescence bullying. Social Psychology of Education. 2005;8:263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Self-esteem and appraisals of parental behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1989;4:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57:110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE, Steinman KJ. Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. Journal of School Health. 2007;77:623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy T. Bullying and victimisation in school children: The role of social identity, problem-solving style, and family and school context. Social Psychology of Education. 2009;12:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, Mackinnon DP. Mediation/indirect effects in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Handbook of Structural equation modeling. New York: The Gilford Press; 2012. pp. 417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehue F, Bolman C, Vollink T, Pouwelse M. Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in relation to adolescents' perception of parenting. Journal of CyberTherapy and Rehabilitation. 2012;5:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani TJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou SN, Stavrinides P. Parenting at home and bullying at school. Social Psychology of Education. 2013;16:165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Williams KR, Sadek S. Understanding bullying and victimization during childhood and adolescence: A mixed methods study. Child Development. 2011;82:295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon JD, Schrodt P. Do parenting styles moderate the association between family conformity orientation and young adults' mental well-being? Journal of Family Communication. 2012;12:151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Liu M. Bootstrapping standard errors and data-model fit statistics. In: Hoyle R, editor. Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hay C, Meldrum R. Bullying victimization and adolescent self-harm: Testing hypotheses from general strain theory. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:446–459. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy KL, Sanders MR, Iyer A. Parenting practices, children’s peer relationships and being bullied at school. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(1):127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Heaven P, Ciarrochi J. Parental styles, gender and the development of hope and self-esteem. European Journal of Personality. 2008;22:707–724. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, Boeding S. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:390–404. doi: 10.1037/a0024519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Fröjd S, Marttunen M. Involvement in bullying and depression in a 2-year follow-up in middle adolescence. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Rantanen P, Rimpelä A. Bullying at school—an indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:661–674. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Bullying at elementary school and problem behaviour in young adulthood: A study of bullying, violence and substance use from age 11 to age 21. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2011;21:136–144. doi: 10.1002/cbm.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides L, Kaloyirou C, Lindsay G. An analysis of the revised olweus bully/victim questionnaire using the rasch measurement model. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;76:781–801. doi: 10.1348/000709905X53499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lereya ST, Samara M, Wolke D. Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Wang J, Simons-Morton B. Bullying victimization and substance use among U.S. adolescents: Mediation by depression. Prevention Science. 2010;11:355–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Wang J, Simons-Morton B. The co-occurrence of substance use and bullying behaviors among U.S. adolescents: Understanding demographic characteristics and social influences. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:1351–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Manly BF. Randomized and Monte Carlo methods in biology. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA. Alcohol, the magic elixir: Stress, expectancy, and the transformation of emotional states. In: Weinstein SP, editor. Stress and addiction. Philadelphia, PA US: Brunner/Mazel; 1987. pp. 302–322. [Google Scholar]

- McGee E, Valentine C, Schulte MT, Brown SA. Peer victimization and alcohol involvement among adolescents self-selecting into a school-based alcohol intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2011;20:253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini E, Modena M, Tani F. Bullying and victimization in adolescence: Concurrent and stable roles and psychological health symptoms. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development. 2009;170:115–133. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.170.2.115-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A, Schlechter M, Netter S, Keehn D. Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL. Gender differences in trajectories of depressive symptomatology and substance use during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1166–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä S, Brunstein-Klomek A, Sillanmäki L, Helenius H, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Sourander A. Childhood bullying behaviors at age eight and substance use at age 18 among males. A nationwide prospective study. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg-Oren N, Cardenas GA, Comerford M, Galea S. An association between bullying behaviors and alcohol use among middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2012;32:761–775. [Google Scholar]

- Radliff KM, Wheaton JE, Robinson K, Morris J. Illuminating the relationship between bullying and substance use among middle and high school youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:569–572. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rhea SA, Nagoshi CT, Wilson JR. Reliability of sibling reports on parental drinking behaviors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:80–84. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MJ. When dissonance fails: On eliminating evaluation apprehension from attitude measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1965;1:28–42. doi: 10.1037/h0021647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. An appraisal-disruption model of alcohol's effects on stress responses in social drinkers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:459–476. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S. Self-esteem, response style and victimization: Possible ways of preventing victimization through parenting and school based training programmes. School Psychology International. 1996;17:347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Stress response dampening. In: Blane HT, Leonard K, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York: Guilford; 1987. pp. 227–271. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvola E, Rose RJ, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Marttunen M, Kaprio J. Early-onset depressive disorders predict the use of addictive substances in adolescence: A prospective study of adolescent finnish twins. Addiction. 2008;103:2045–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skues JL, Cunningham EG, Pokharel T. The influence of bullying behaviours on sense of school connectedness, motivation and self-esteem. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2005;15:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Giancola P, Dawes M, Blackson T, Mezzich A, Clark DB. Etiology of early age onset substance use disorder: A maturational perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:657–683. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, Tein J. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:241–269. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D'Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver FJR, Hambleton RK. Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. European Psychologist. 1996;1:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Luk JW. Patterns of adolescent bullying behaviors: Physical, verbal, exclusion, rumor, and cyber. Journal of School Psychology. 2012;50:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Luk JW, Nansel TR. Co-occurrence of victimization from five subtypes of bullying: Physical, verbal, social exclusion, spreading rumors, and cyber. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:1103–1112. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Nagoshi CT, Dennis DA. Alcohol norms and expectations as predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18(4):461–476. doi: 10.3109/00952999209051042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormington SV, Anderson KG, Tomlinson KL, Brown SA. Alcohol and other drug use in middle school: The interplay of gender, peer victimization, and supportive social relationships. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2013;33:610–634. doi: 10.1177/0272431612453650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Liu X, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Musa G, Cook JA. The relationship between depressive symptom levels and subsequent increases in substance use among youth with severe emotional disturbance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:520–527. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Corley RP, Stallings MC, Rhee SH, Crowley TJ, Hewitt JK. Substance use, abuse and dependence in adolescence: Prevalence, symptom profiles and correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:309–322. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT. Parsing the undercontrol–disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: A multilevel developmental problem. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]