Abstract

Aim

To explore associations between health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and comorbidities in youth with Type 2 diabetes.

Patients & methods

Of 699 youth in the TODAY study, 685 (98%) had baseline HRQOL data, 649 (93%) at 6 months and 583 (83%) at 24 months. Comorbidities were defined by sustained abnormal values and treatment regimens.

Results

At baseline, 22.2% of participants demonstrated impaired HRQOL. Only depressive symptoms distinguished those with versus without impaired HRQOL and were significantly related to later impaired HRQOL (p < 0.0001). A significant correspondence between impaired HRQOL and number of comorbidities (p = 0.0003) was noted, but was driven by the presence of depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Results emphasize the need for evaluation of depressive symptoms. Other comorbidities did not have a significant impact on HRQOL in this cohort.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, microalbuminuria, pediatric Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) in youth has become a public health concern, and the development of complications appears accelerated when compared with adults with equivalent diabetes duration [1,2]. Initial studies suggest that comorbidities are observed early in the disease course in patients with youth-onset T2D, making prevention or treatment of comorbid conditions of utmost concern in this population [3–5]. Complications such as hypertension, microalbuminuria, dyslipidemia and depression have the potential to add significant health burden and expense, and have been associated with diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in adults [6]. It is important to understand whether the associations between comorbidities and perceived health status observed in the adult population with T2D are present in youth with T2D.

Studies in adults with T2D report that HRQOL worsens as diabetes-related conditions and complications increase in number, severity and duration [6]. The long-term follow-up (>23 years) of individuals with T1D [7] also shows that worsening metabolic control, serious diabetes complications and the emergence of psychiatric conditions are associated with increased HRQOL impairment. However, within an average 2.7 years of diagnosis, T1D youth report very similar HRQOL to their peers without illness [8]. Less is known about how comorbid conditions may influence self-reported health perceptions in adolescents or young adults with T2D. Some studies have found that within the first several years of disease onset, youth with T2D may have poorer HRQOL overall compared with those with T1D [9–11] but more prospective research is needed.

The TODAY randomized clinical trial (Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth) provided an opportunity to explore the effects of select comorbid conditions on HRQOL in a large well-characterized sample. Prior reports from TODAY have found that hypertension, dyslipidemia and microalbuminuria were frequently encountered at baseline and, despite aggressive management and therapies, new cases were diagnosed during follow-up of 2–6.5 years (average 3.9 years) [1,2]. In addition, 15% of TODAY participants had clinically significant depressive symptoms at baseline [12].

The primary objective of this analysis was to report on the association of comorbidities and impaired HRQOL in the TODAY cohort at baseline and during the study. Five comorbidities were examined both singly and in combination: hypertension, microalbuminuria, LDL dyslipidemia, triglyceride dyslipidemia and clinically elevated depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that the presence and accumulation of comorbid conditions would affect HRQOL in youth with T2D.

Patients & methods

TODAY design & primary results

The collaborative study group included 15 clinical centers, a data coordinating center and central laboratories and reading centers. Study design has been reported [13] and is briefly summarized. Between July 2004 and February 2009, 699 youth were enrolled between the ages of 10 and 17 years, with T2D (pancreatic autoantibody negative) diagnosed by American Diabetes Association criteria of less than 2 years duration, and with a BMI ≥85th percentile. Medically-related exclusion criteria included: refractory hypertension, hyperlipidemia or anemia (i.e., abnormal values despite appropriate medical therapy); use of steroids or medications known to affect insulin sensitivity or secretion, weight gain or loss, or the metabolism of study drugs; and other significant organ system illness or conditions (including psychiatric or developmental disorders) that would prevent participation in the opinion of the investigator. To be eligible, all TODAY participants had to identify an adult caregiver who agreed to support the youth participant in the study, including accompanying to all visits.

Eligible subjects also had to successfully complete a 2–6 month prerandomization runin period that included attaining glycemic control (HbA1c <8% measured monthly for at least 2 months) on 1000–2000 mg of metformin monotherapy, mastering standard diabetes education, demonstrating ≥80% adherence to study medication (percent of number of pills taken divided by number prescribed by pill count) for at least 8 of 12 consecutive weeks, and attending study visits. Eligible participants were randomized to one of three treatment arms: metformin (M), metformin plus rosiglitazone (M+R) and metformin plus an intensive lifestyle program (M+L). The primary objective was to compare the three arms on time to treatment failure – that is, loss of glycemic control defined as either HbA1c ≥8% over a 6-month period or inability to wean from temporary insulin therapy within 3 months following acute metabolic decompensation. After an average follow-up of 3.9 years, 319 (45.6%) lost glycemic control; M+R was superior to M (p = 0.006) and M+L was intermediate but not different from M [14].

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions; parents signed informed consent for a minor child, and youth signed informed assent according to local practice.

Data collection & measurements

Participants were seen every 2 months in year 1 and quarterly thereafter for purposes of medical monitoring and management and distribution of study drug; physical measurements were made and blood was drawn and sent to a central study laboratory [14]. Outcome data collection visits occurred at baseline, 6 months, 24 months and then annually.

Baseline characteristics

Race-ethnicity was determined by self report on two separate items: participants checked Hispanic/Latino ethnicity either yes or no and checked as many racial categories as needed. Participants were categorized as non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic and other (combination of categories too small for separate analysis). Household education was the highest education level attained by parent/guardian or current spouse/partner; 15 categories were collapsed into four for purposes of analysis. Annual household income of all persons living in the household in the past year was collected by self-report of participant and family member(s) present at the baseline visit; nine categories were collapsed into three for purposes of analysis. Participants were also asked whether they lived with their biological mother and/or father and total number living in the household.

Quality of life

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) measured youth perception of HRQOL. The Total Scale Score was computed using all 23 items, the Psychosocial Health Summary Score 15 items and the Physical Health Summary Score 8 items. Each score could range from 0 to 100. Impaired HRQOL was determined by cut-offs (mean – 1 SD) derived from over 5000 healthy youth [15] as follows: 71.19 ( = 83.84–12.65) for Total; 67.78 ( = 81.87–14.09) for Psychosocial; 74.03 ( = 87.53–13.50) for Physical.

Comorbidities

Diagnostic criteria for hypertension, dyslipidemia and microalbuminuria included consistently abnormal values and/or taking appropriate therapy. The cut-offs used have been described in detail elsewhere [4]. Briefly, cut-offs were: blood pressure ≥30/80 or ≥95th percentile for age, gender and height; LDL-cholesterol ≥130 mg/dl; triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl; and urine albumin:creatinine ratio ≥30 μg/mg. Once the diagnosis was made, it was treated according to study protocol and considered chronic. Depressive symptoms were assessed using either the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) for participants <16 years [16] or the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) for those ≥16 years [17]. Total scores were calculated for each instrument; a cut-off score ≥13 on the CDI and ≥14 on the BDI-II indicated clinically elevated levels of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms could be present or absent at each assessment.

Statistical analysis

Hypothesis testing applied χ2 for categorical data and one-way analysis of variance for continuous data. Significance was defined as p < 0.05 with no adjustment for multiple testing; the trial was powered for the primary outcome only.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the TODAY cohort of 699, 685 (98%) had HRQOL data at baseline, 649 (93%) at 6 months, and 583 (83%) at 24 months. At baseline, average PedsQL Total Scale Score was 88.4 (SD 12.5, range 37–100) and 22.2% had impaired HRQOL. Table 1 gives baseline characteristics overall and by HRQOL status (impaired/not impaired). Age, sex and race-ethnicity were representative of youth-onset T2D. Although the total sample was predominantly obese, participants with impaired HRQOL at baseline were significantly heavier than those not impaired (BMI z-score 2.33 vs 2.19, p = 0.0008; BMI ≥95th percentile 95.4 vs 86.3%, p = 0.0068). Several indicators of socioeconomic status (household highest level of education, total annual household income, total number in household) were not different between the two subgroups, but percent living with both biological parents was significantly different (30.2% impaired vs 41.4% not impaired; p = 0.0036).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (mean [standard deviation] or percentage) for demographics and characteristics at baseline overall and by impaired health-related quality of life at baseline.

| Characteristics determined at baseline | Overall (n = 685) | HRQOL |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired (n = 152; 22.2%) | Not impaired (n = 533; 77.8%) | p-value | ||

| Age (years); mean (SD) | 14.0 (2.0) | 13.9 (2.0) | 14.0 (2.0) | 0.5442 |

|

| ||||

| Female | 65.0% | 69.1% | 63.8% | 0.2279 |

|

| ||||

| BMI z-score; mean (SD) | 2.22 (0.47) | 2.33 (0.41) | 2.19 (0.48) | 0.0008 |

|

| ||||

| BMI percentile: | 0.0068 | |||

| – Overweight (85% to <95%) | 10.2% | 4.6% | 11.8% | |

| – Obese (≥95%) | 88.3% | 95.4% | 86.3% | |

|

| ||||

| Race: | 0.2189 | |||

| – Non-Hispanic black | 32.5% | 36.2% | 31.5% | |

| – Hispanic | 39.6% | 32.2% | 41.6% | |

| – Non-Hispanic white | 20.6% | 23.0% | 20.0% | |

| – Other | 7.3% | 8.6% | 6.9% | |

|

| ||||

| Household highest level education: | 0.3023 | |||

| – Less than high school | 26.5% | 21.6% | 27.9% | |

| – High school or equivalent | 25.0% | 29.1% | 23.9% | |

| – Some college or associates degree | 31.8% | 30.4% | 32.2% | |

| – Graduate degree | 16.7% | 18.9% | 16.0% | |

|

| ||||

| Total annual household income: | 0.2622 | |||

| – <US$25,000 | 41.5% | 42.1% | 41.3% | |

| – US$25,000–49,999 | 33.7% | 37.9% | 32.4% | |

| – ≥US$50,000 | 24.8% | 20.0% | 26.3% | |

|

| ||||

| Lives with biological parents: | 0.0036 | |||

| – Both biological parents | 39.0% | 30.2% | 41.4% | |

| – Biological mother only | 46.7% | 52.3% | 45.1% | |

| – Biological father only | 5.1% | 2.7% | 5.8% | |

| – Neither biological parent | 9.2% | 14.8% | 7.7% | |

|

| ||||

| Total number in household: | 0.3810 | |||

| – 2 | 9.5% | 13.4% | 8.4% | |

| – 3 | 18.7% | 16.8% | 19.2% | |

| – 4 | 30.9% | 30.9% | 30.9% | |

| – 5 | 21.5% | 18.8% | 22.3% | |

| – >5 | 19.4% | 20.1% | 19.2% | |

|

| ||||

| Treatment group assignment: | 0.7869 | |||

| – Metformin alone | 32.9% | 33.5% | 32.7% | |

| – Metformin + rosiglitazone | 33.9% | 31.6% | 34.5% | |

| – Metformin + lifestyle program | 33.2% | 34.9% | 32.8% | |

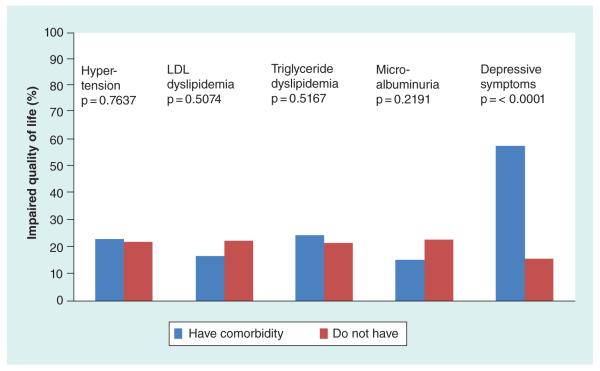

Distribution of impaired HRQOL for each comorbidity

Figure 1 shows the relationship of baseline impaired HRQOL with baseline status of each of the five comorbidities. Only the presence or absence of depressive symptoms distinguished those with impaired HRQOL from those without. The analysis was repeated at 6 and 24 months and for the two HRQOL subscales with identical results (data not shown).

Figure 1. Distribution of impaired HRQOL by each comorbidity at baseline.

Only the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms (by self-report) was associated with impaired HRQOL.

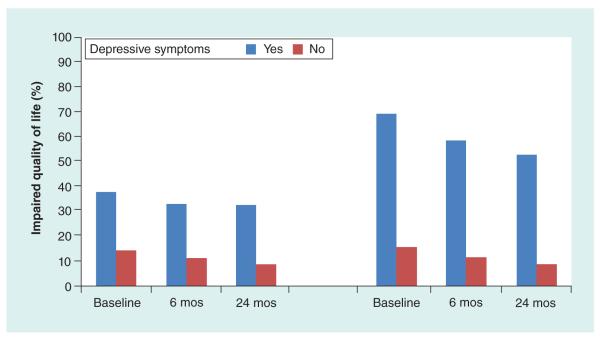

There was a significant negative correlation (r = −0.483, p < 0.0001) between total scores on the BDI and PedsQL at baseline in the TODAY cohort. Comparison of the PedsQL and the BDI shows some overlap between the PedsQL Psychosocial Health Summary Score (15 items addressing problems with feelings, getting along with others and school) and the BDI. The analysis was rerun testing for association between presence/absence of depressive symptoms and HRQOL separated into the Physical and Psychosocial Health Summary Scores. Figure 2 shows that, although much less pronounced in the subscale combining items addressing health and activities, there remains a significant association for both Physical and Psychosocial constructs.

Figure 2. Percent impaired HRQOL by presence of clinically depressive symptom summary subscales across visit month.

The significant association between presence of clinically depressive symptoms (total score) and impaired HRQOL was repeated for each subscale: (A) Physical Health Summary Score and (B) Psychosocial Health Summary Score: all p < 0.0001. The difference was less pronounced for the Physical Score than the Psychosocial Score (B), likely due in part to some overlap between the PedsQL Psychosocial Score (15 items addressing problems with feelings, getting along with others and school) and the BDI.

Effect of early comorbidity on later HRQOL

We examined whether the presence of a comorbidity had a ‘predictive’ effect on future HRQOL by testing the relationship between baseline comorbid condition versus impaired HRQOL at 6 months and at 24 months, and between comorbid condition early (at baseline or 6 months) versus impaired HRQOL at 24 months. In all cases, only depressive symptoms were significantly related to subsequent impaired HRQOL (all p < 0.0001).

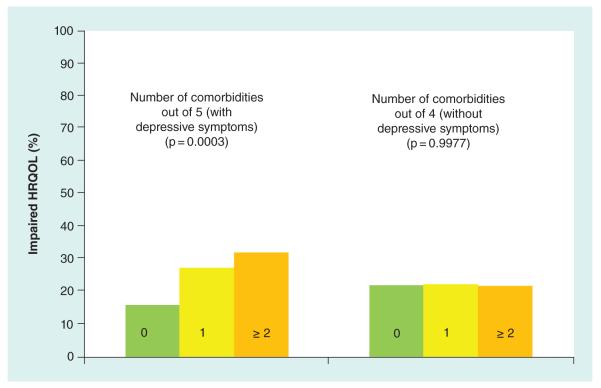

Cumulative effect of comorbidities on HRQOL

Participants were categorized as having 0, 1, or 2 or more comorbidities at each of the three time points. Figure 3 shows results at baseline. When all five comorbidities were included there was a significant correspondence between higher percent with impaired HRQOL and number of comorbidities (p = 0.0003). However, when the analysis was repeated with only four comorbidities not including depressive symptoms, there was no relationship between number of comorbidities and percent with impaired HRQOL. Results were the same at 6 and 24 months.

Figure 3. Percentage impaired HRQOL by presence of multiple comorbidities at baseline.

Participants were categorized as having 0 (56%), one (32%) or two or more (12%) comorbidities. When all five comorbidities were included there was a significant correspondence between impaired HRQOL and number of comorbidities (p = 0.0003). However, when the analysis was repeated with only four comorbidities not including depressive symptoms, there was no relationship between number of comorbidities and impaired HRQOL. Results were the same at 6 and 24 months.

Trend in HRQOL over time

Participants were categorized as either having declined in HRQOL (defined as changing from not impaired to impaired categories between visits) or improved (defined as changing from impaired to not impaired). Participants who were impaired at all visits (n = 28) or not impaired at all visits (n = 376) were excluded from this analysis. The groups were compared by whether the participant ever had the comorbidity over the 24 months of study. There was no relationship between decline or improvement in HRQOL and presence of any comorbidity.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of comorbid medical conditions including hypertension, microalbuminuria, dyslipidemia and depressive symptoms on HRQOL over time in a large sample of youth with T2D. At baseline, less than a quarter of the TODAY cohort reported poor perceived HRQOL. Of the comorbid conditions examined, only the presence of clinically elevated depressive symptoms significantly predicted HRQOL impairment at any time point. Roberto et al. [18] reported similar results, with a significant negative correlation (r = −0.548, p < 0.01) between total scores on the BDI and PedsQL in a sample of adolescents (ages 14–18 years) enrolled in a bariatric surgery program at a large, urban medical center. The relationship between elevated depressive symptoms and impaired HRQOL was consistent across TODAY study visits (baseline, 6 and 24 months). There was no cumulative effect of other medical comorbidities on perceived health, nor any relationship between perceived health declines or improvements and the presence of any other comorbidity.

Our main finding that depressive symptoms are a dominant predictor of HRQOL impairment over 2 years is consistent with the finding in previous studies of adults with diabetes that depression or a history of psychiatric events relates to HRQOL [19] even over long periods of time [7]. A study of the relationship of HRQOL to depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with T1D also found significant associations [9]. Our study extends these findings to youth with recent-onset T2D. The negative toll depression may have on a youth’s quality of life should be discussed with youth and with their families; this is particularly important given the challenges faced by families in following through with referrals for diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders [20]. Youth with either T2D or T1D are at elevated risk for mood disorders [21,22] and their healthcare providers should be equipped with resources to screen and/or make appropriate referrals. Interdisciplinary teams, including psychologists within the clinic or hospital, could assist in addressing this vital need [23], particularly since depression has been shown to be successfully treated in youth in this age group [24].

Analysis of TODAY data also revealed that, unlike findings in adults with T2D [6], the presence of hypertension, dyslipidemia and micro-albuminuria (alone or in combination) does not appear to significantly affect the HRQOL of youth with T2D at this early stage in their illness. In our sample, these seemingly ‘silent’ comorbidities did not have any measurable impact on the day-to-day functioning of youth based upon their reported HRQOL. As with T1D, the psychological and social needs and demands of adolescence may simply supersede the needs and demands of this chronic medical condition. Very similar findings have been reported in obese adolescents without diabetes [25]. Therefore, one challenge presented by this finding is how to implement strategies to promote positive self-management behaviors for youth with T2D who are not affected by chronic health concerns, given an apparently accelerated development of diabetic complications.

The robust relationship between HRQOL and elevated depressive symptoms and the lack of a relationship between HRQOL and the other comorbidities may suggest that those patients with indicators of depression may develop barriers to diabetes self-care management. Thus it may be appropriate to address psychosocial needs of youth with T2D as a first step to a more broad-based discussion of chronic illness self-management and other self-care behaviors (including weight management). We also found that at baseline, family composition was related to HRQOL – that is, youth who were living with both biological parents were less often in the impaired HRQOL group. While inclusion of this information as part of a clinical assessment would require an individualized approach appreciating the diversity of family circumstance, the association warrants further investigation.

This study has several strengths including the large sample size, the repeated measurements over time and the determination of comorbid conditions applying standardized criteria and measurements made by certified staff and/or laboratories. Limitations include the fact that the TODAY sample may not be representative of youth with T2D at large due to the stringent eligibility criteria. In addition, the BDI/CDI and PedsQOL rely entirely on self-report and the former indicate presence of depressive symptoms but not a diagnosis of depression.

Conclusion

In summary, impaired HRQOL in the TODAY cohort of youth with T2D was related only to clinically elevated depressive symptoms assessed by self report survey. This relationship was consistently identified over a 2-year period, and contrary to expectation, the presence of the other comorbidities or of multiple comorbidities did not significantly impact HRQOL at any time point. Additional correlates, though not the primary focus of this study, were identified at baseline including degree of obesity and absence of one or both biological parents from the home. These findings, taken together, may assist in identifying youth who may be vulnerable to challenges in self-management and need additional screening and support to cope with their chronic condition. They also point to the importance of implementing interventions to target weight control that take into account the psychological and overall health perspectives of youth in the early stages of their T2D diagnosis.

In conclusion, these results support the importance of early screening for depressive symptoms in youth with T2D. Whether treatment for depression will improve HRQOL is a subject for future research.

Future perspective

Youth with T2D may present with varying degrees of psychological vulnerability that may be compounded by challenging socio-economic environments and comorbidities. The TODAY clinical trial addressed the need to document the extent of this phenomenon. Our findings suggest that screening for depression is an integral part of any comprehensive approach to the clinical management of T2D in this population. In addition, we recommend that future research continue to evaluate and document the impact psychological health plays in the clinical management of T2D with this ever increasing group. An examination of the association between time since diagnosis and measures of psychological health may provide insights; because eligible participants in TODAY had to have been diagnosed <2 years, the range was too narrow in the TODAY cohort to perform a meaningful analysis.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00081328

Practice points.

Impaired HRQOL in the TODAY cohort of youth with Type 2 diabetes (T2D) was related only to clinically elevated depressive symptoms assessed by self report survey.

The presence of the other comorbidities or of multiple comorbidities did not significantly impact HRQOL at any time point.

The main finding that depressive symptoms are a dominant predictor of HRQOL impairment over 2 years is consistent with findings in previous studies of adults with diabetes.

Additional correlates were identified including degree of obesity and absence of one or both biological parents from the home.

The findings, taken together, may assist in identifying youth who need additional screening and support to cope with their chronic condition.

The findings point to the importance of implementing interventions to target weight control that take into account the psychological and overall health perspectives of youth in the early stages of their T2D diagnosis.

The results support the importance of early screening for depressive symptoms in youth with T2D.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation and guidance of the American Indian partners associated with the clinical center located at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, including members of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was completed with funding from NIDDK and the NIH Office of the Director (OD) through grants U01-DK61212, U01-DK61230, U01-DK61239, U01-DK61242 and U01-DK61254; from the National Center for Research Resources General Clinical Research Centers Program grant numbers M01-RR00036 (Washington University School of Medicine), M01-RR00043-45 (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles), M01-RR00069 (University of Colorado Denver), M01-RR00084 (Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), M01-RR01066 (Massachusetts General Hospital), M01-RR00125 (Yale University) and M01-RR14467 (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center); and from the NCRR Clinical and Translational Science Awards grant numbers UL1-RR024134 (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia), UL1-RR024139 (Yale University), UL1-RR024153 (Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), UL1-RR024989 (Case Western Reserve University), UL1-RR024992 (Washington University in St Louis), UL1-RR025758 (Massachusetts General Hospital) and UL1-RR025780 (University of Colorado Denver). The TODAY Study Group thanks the following companies for donations in support of the study’s efforts: Becton, Dickinson and Company; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly and Company; GlaxoSmithKline; LifeScan, Inc.; Pfizer; Sanofi Aventis. N Walders-Abramson is a paid consultant for Daiichi Sankyo Pharma Development. PM Yasuda runs monthly diabetes support groups for families with children with diabetes co-sponsored by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and received US$2500 last year.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional information

Materials developed and used for the TODAY standard diabetes education program and the intensive lifestyle intervention program are available to the public at https://today.bsc.gwu.edu

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The NIDDK science officer assigned to TODAY was involved in all aspects of the research, including design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, review and approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. K Hirst confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the respective Tribal and Indian Health Service Institution Review Boards or their members.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

- 1.TODAY Study Group Rapid rise in hypertension and nephropathy in youth with Type 2 diabetes: the TODAY clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1735–1741. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2420. • Provides background and details of the TODAY clinical trial.

- 2.TODAY Study Group Lipid and inflammatory cardiovascular risk worsens over 3 years in youth with Type 2 diabetes: the TODAY clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1758–1764. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2388. • Provides background and details of the TODAY clinical trial.

- 3.Copeland KC, Silverstein J, Moore KR, et al. Management of newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):364–382. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3494. • Provides background and details of the TODAY clinical trial.

- 4.Copeland KC, Zeitler P, Geffner M, et al. Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset Type 2 diabetes: the TODAY cohort at baseline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96(1):159–167. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1642. • Provides background and details of the TODAY clinical trial.

- 5.Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J. Pediatr. 2010;157(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021. • Describe similar studies and results performed in other populations.

- 6.Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Wittenberg E, et al. Correlates of health-related quality of life in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49(7):1489–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0249-9. • Describe similar studies and results performed in other populations.

- 7.Jacobson AM, Braffett BH, Cleary PA, Gubitosi-Klug RA, Larkin ME, DCCT/EDIC Research Group The long-term effects of Type 1 diabetes treatment and complications on health-related quality of life: a 23 year follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications cohort. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3131–3138. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2109. • Describes similar studies and results performed in other populations.

- 8.Laffel LM, Connell A, Vangsness L, Goebel-Fabbri A, Mansfield A, Anderson BJ. General quality of life in youth with Type 1 diabetes: relationship to patient management and diabetes-specific family conflict. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3067–3073. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naughton MJ, Ruggiero AM, Lawrence JM, et al. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus: SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008;162(7):649–657. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hood KK, Beavers DP, Yi-Frazier J, et al. Psychosocial burden and glycemic control during the first 6 years of diabetes: results from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. J. Adolesc. Health. 2014;55(4):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Jacobs JR, Gottschalk M, Kaufman F, Jones KL. The PedsQL in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life inventory generic core scales and Type 1 diabetes module. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):631–637. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson BJ, Edelstein S, Abramson NW, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in adolescents with Type 2 diabetes: baseline data from the TODAY study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2205–2207. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.TODAY Study Group Treatment options for Type 2 diabetes in adolescents and youth: a study of the comparative efficacy of metformin alone or in combination with rosiglitazone or lifestyle intervention in adolescents with Type 2 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2007;8:74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TODAY Study Group A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with Type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2247–2256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: a comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Quality Life Outcome. 2007;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Multi-Health Systems Inc.; North Tonawanda, NY, USA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory II. Psychological Corp.; San Antonio, TX, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberto CA, Sysko R, Bush J, et al. Clinical correlates of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale in a sample of obese adolescents seeking bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2012;20:533–539. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali S, Stone M, Skinner TC, Robertson N, Davies M, Khunti K. The association between depression and health-related quality of life in people with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2010;26(2):75–89. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radovic A, Farris C, Reynods K, Reis EC, Miller E, Bradley S. Primary care providers beliefs about teen and parent barriers to depression care. J. Dev. Behavioral Ped. 2014;35(8):534–538. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delamater AM. Psychological care of children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl. 12):175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polonsky WH. Emotional and quality-of-life aspects of diabetes management. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2002;2(2):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bitsko MJ, Bean MK, Bart S, Foster RH, Thacker L, Francis GL. Psychological treatment improves hemoglobin A1c outcomes in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 2013;20(3):333–342. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9350-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SY. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2006;132(1):132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walders-Abramson N, Nadeau KJ, Kelsey MM, et al. Psychological functioning in adolescents with obesity co-morbidities. Child Obes. 2013;9(4):319–325. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]