Abstract

Amyloid-β proteins (Aβ) of 42 (Aβ42) and 40 aa (Aβ40) accumulate as senile plaques (SP) and cerebrovascular amyloid protein deposits that are defining diagnostic features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A number of rare mutations linked to familial AD (FAD) on the Aβ precursor protein (APP), Presenilin-1 (PS1), Presenilin-2 (PS2), Adamalysin10, and other genetic risk factors for sporadic AD such as the ε4 allele of Apolipoprotein E (ApoE-ε4) foster the accumulation of Aβ and also induce the entire spectrum of pathology associated with the disease. Aβ accumulation is therefore a key pathological event and a prime target for the prevention and treatment of AD. APP is sequentially processed by β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE1) and γ-secretase, a multisubunit PS1/PS2-containing integral membrane protease, to generate Aβ. Although Aβ accumulates in all forms of AD, the only pathways known to be affected in FAD increase Aβ production by APP gene duplication or via base substitutions on APP and γ-secretase subunits PS1 and PS2 that either specifically increase the yield of the longer Aβ42 or both Aβ40 and Aβ42. However, the vast majority of AD patients accumulate Aβ without these known mutations. This led to proposals that impairment of Aβ degradation or clearance may play a key role in AD pathogenesis. Several candidate enzymes, including Insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), Neprilysin (NEP), Endothelin-converting enzyme (ECE), Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), Plasmin, and Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have been identified and some have even been successfully evaluated in animal models. Several studies also have demonstrated the capacity of γ-secretase inhibitors to paradoxically increase the yield of Aβ and we have recently established that the mechanism is by skirting Aβ degradation. This review outlines major cellular pathways of Aβ degradation to provide a basis for future efforts to fully characterize the panel of pathways responsible for Aβ turnover.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid β degradation, amyloid β peptide, endothelin-converting enzyme, insulin-degrading enzyme, neprilysin, neurodegeneration

1. INTRODUCTION

AD is the most common form of dementia in the elderly population in the United States, with age being the number one risk factor but the occurrence of a number of cognitively normal centenarians argues against the aging process directly causing dementia. It has been reported that over 50% of people who are 85 years or older suffer from the disease [1]. Unfortunately, all FDA approved treatments for AD only provide temporary cognitive improvement with negligible disease modifying effect on the neuropathology [2, 3]. Since sporadic AD generally manifests late in life, multiple environmental, physiological and cellular processes appear to modify the risk for developing the disease [4]. It may be possible to target one or more of these hits to prevent the disease, but the repeated failure of clinical trials suggests that treatment treatments devised so far are missing key therapeutic targets. Therefore, it is important to understand the silent biochemical cascades involved in neurodegeneration, hoping that these will walk us toward the disease etiology. The reality in the AD field is that yet we have no clue as to its cause, “an embarrassment of riches” where all bets are on, from hormonal deficiencies to viral reactivation [5].

As a central component of life, the levels and types of proteins are important in determining the structure of cells and in optimizing their role within the context of their function. In addition to controlling gene expression at the transcriptional and translational levels, the steady state concentration of a particular protein within a cell is also determined by its turnover rate. A plethora of studies have demonstrated that regulation of proteolysis play a key role in many processes critical to cell survival. Such mechanisms are also central to many physiologic pathways in multicellular organisms such as blood clotting, complement activation, cell cycle, cell differentiation and embryo growth pattern and development. Specific proteins are called into action at defined times during development and are subsequently degraded after completing their task. Failure of these processes is associated with substantive congenital morbidity and mortality. At the other end of life, these processes can significantly contribute to age related disease. While some structural proteins remain stable for prolonged periods, others with regulatory function are constantly degraded; i.e., cleaved to either activate or inactivate precursors [6]. If, however, the proteins are not degraded, then their subsequent accumulation can significantly affect their regulatory activity to ultimately cause dysfunction. Cellular homeostasis must therefore be maintained by turnover mechanisms to ensure a fastidious balance. This is also the case with clearance of Aβ from cells in the normal brain and in AD patients. Here in, this review highlights the predominant cellular mechanisms that have been demonstrated to affect the trafficking and clearance of the Aβ peptide within the brain.

AD is characterized by widespread neuronal degeneration and synaptic loss affecting the hippocampus, cortex and other brain regions, resulting in diffuse brain atrophy. However, senile plaques (SP) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), the two microscopic hallmark lesions originally described by Alois Alzheimer, are still considered the most important pathological markers of AD [7]. SPs are primarily composed of Aβ and NFTS of hyperphosphorylated microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) accumulates in the form of paired helical filaments. Whether Aβ accumulation or hyperphosphorylated tau contribute to the disease pathogenesis or are merely bystander markers of the disorder, remains a matter of intense debate [8–12]. Nevertheless, Aβ accumulation is found in all forms of the disease and its production is specifically altered by FAD mutations even in cultured cells The convergence of FAD mutations on APP and presenilins to specifically increase Aβ, which then accumulates as SPs, lays the foundation for the widely recognized ‘amyloid hypothesis’ of AD [13]. This hypothesis proposes that abnormally high levels of Aβ trigger a cascade of events leading to neurodegeneration. The hypothesis is supported by four main observations: i)-amyloid accumulation generally precedes the development of MAPT abnormalities by many years [14, 15], ii)-mutations in the APP gene cause a form of familial AD that is neuropathologically indistinguishable from the sporadic form [16]; iii)- Aβ oligomers are neurotoxic [17–19] and iv) APP variants that reduce Aβ production protect against AD pathogenesis and increase longevity [20]. Thus, understanding the regulation of Aβ production and turnover is critical to identify potential therapeutic targets [20–24].

2. AMYLOID PRODUCTION PATHWAYS

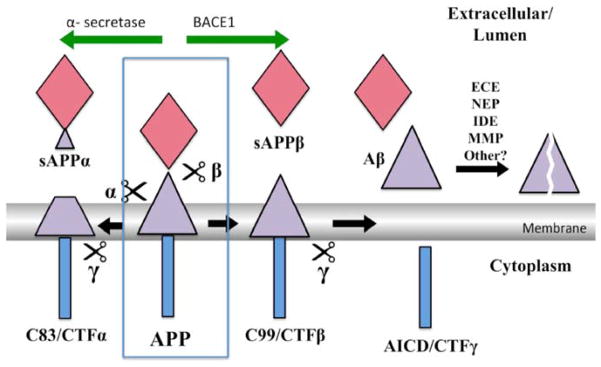

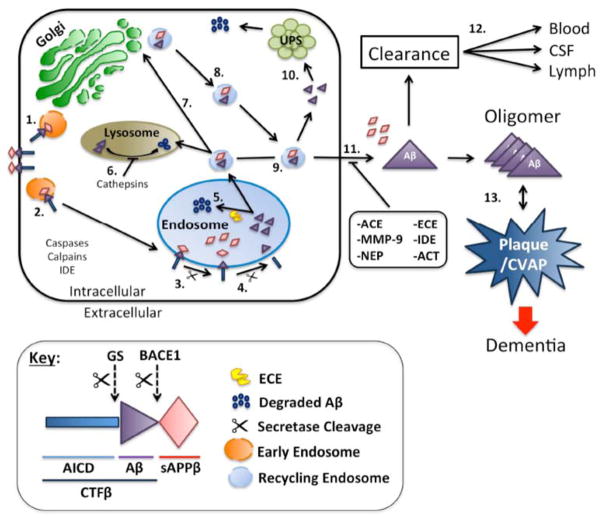

Aβ is produced following sequential cleavage ofa larger precursor protein, APP, which has become the major subject of study in AD pathogenesis. APP is a large type-I integral membrane protein of 695–770 aa that is sequentially processed by either BACE1 or α-secretase to carboxy-terminal fragments of 99 aa (CTFβ) or 83 aa (CTFα). An intramembrane protease, γ-secretase, cleaves CTFβ to 4 kDa Aβ and CTFα to a smaller 3 kDa fragment named P3 or Aα (Fig. 1). Other Aβ-like fragments have also been described, but they are relatively minor [25]. Several reviews, have detailed the processing pathway of APP [13]. The compartmentalization of the processing events is a critical part of its regulation [26]. In particular, this report demonstrated that BACE1 and α-secretase processing takes place in two different cellular compartments. Although BACE1 represents a minor pathway for APP processing, the enzyme is not limiting and overexpression of APP results in a proportionately higher CTFβ and Aβ yield. Finally inhibiting α-secretase does not increase Aβ production, showing that although it cleaves inside the Aβ sequence and represents the major APP processing pathway, it does not limit Aβ biogenesis [26]. The exact compartments involved in this process vary by cell type as Aβ is generated in both constitutive and regulated secretory pathways [27, 28]. It is generally accepted that APP is first transported to the cell surface and processed either in the secretory pathway or at the surface by a constitutive or inducible form of α-secretase to CTFα [29–32]. The membrane-bound CTFα fragment is processed by γ-secretase which appears to reside within multiple locations including the Golgi apparatus and the cell surface [33]. APP not processed by α-secretase becomes internalized into endocytic vesicles, where BACE1, an aspartyl protease with an acid pH optimum, cleaves it to generate CTFβ. This, in turn, is further processed by γ-secretase to Aβ40 and Aβ42 that gets transported to the cell surface and secreted via recycling vesicles (Fig. 1, 2). It has been proposed that accumulated Aβ generates oligomers that interact with phosphorylated MAPT to induce synaptic dysfunction [34]. In addition to genetics, epigenetics, and environment, other factors including dietary imbalance, exercise, and early-life exposure to metals and pesticides (as described in the ‘LEARn’ model) also play an important and complex role in the development of dementia[35, 36].

Fig. 1. Key APP processing pathways.

The neuronal form of APP is a type-1 integral-membrane glycoprotein of 695 aa with a large ectodomain a single transmembrane domain and a short intracellular domain (Blue box). A group of metalloproteases named α-secretase cleave APP inside the Aβ sequence (violet triangle) between residues 16 and 17 to produce a secreted fragment of 612 aa, sAPPα, and a cellular fragment of 83 aa - CTFα. This is the major pathway and accounts for 80–90% of APP turnover. In the amyloidogenic pathway, BACE1 (β) cleaves APP to the secreted fragment, sAPPβ (red diamond), of 596 aa and membrane-bound fragment CTFβ of 99 aa. Which in turn is processed to Aβ by γ-secretase. Aβ is degraded and cleared by multiple known and unknown pathways as shown.

Fig. 2. Model showing the cell biology of Aβ production and degradation.

APP is synthesized in the ER and gets transported to the Golgi apparatus where it is packaged to vesicles (orange circles) for delivery to the cell surface (Step 1.). APP that does not get processed by the α-secretase in the secretary pathway is internalized into endosomes (Large blue circles), which are acidic compartments (Steps 2 and 3). BACE1 cleaves APP in the endosome to generate CTFβ, which is then processed to Aβ by γ-secretase within the endosome (Step 4). In neurons, a large fraction of the Aβ generated in this compartment is degraded by ECE and unknown proteases (Step 5). Aβ that escapes this pathway may be transported to the lysosome and degraded (Step 6). Alternatively, Aβ containing recycling vesicles (small blue circles) can be recycled to the cell surface either via the Golgi apparatus (Steps 7 and 8)or directly from the endosome to the cell surface (Step 9). Aβ may be released from recycling vesicles to the UPS for degradation (Step 10) or get degraded at the cell surface by other known pathways such as NEP, IDE, MMP-9 or by other unidentified pathways. The Aβ that escapes degradation may be drained into the cerebrospinal fluid or cleared into the lymphatic or vascular circulation. Failure of all these redundant turnover mechanisms will lead to accumulation and aggregation of Aβ into SP and as CVAP.

3. GENE VARIANTS LINK Aβ TO AD

Although FAD only accounts for a small fraction of AD cases (~5%), these mutations on APP, PS1 and PS2induce the entire range of pathology starting with increase in Aβ accumulation to SPs, passing through NFT formation and leading to synaptic dysfunction, neuron loss, brain atrophy and dementia [9, 37, 38]. Despite the strong genetic and toxic connection between Aβ and AD, the topic remains controversial with some investigators dismissing its role as an epiphenomenon [39]. Most of the argument revolves around a direct role for Aβ toxicity in the AD-associated neurodegeneration as a potential treatment target. Indeed, with failure of clinical trials against Aβ, these arguments have suddenly become quite popular. However, in vivo labeling for Aβ provided evidence that these lesions accumulate as early as twenty years before the onset of dementia and highlight the multistep process of dementia with Aβ serving as a potential preclinical target, like cholesterol for cardiovascular disease [40–43]. These imaging studies have led to a new hypothesis that SPs and even NFTs are early preclinical stages of the disease and that even some visible neurodegeneration predates the onset of mild dementia, suggesting that treatments to reduce Aβ and MAPT must start early during the disease course for subjects at high risk for prevention of dementia [42, 43]. The prevention focus has become widely recognized and discussed [44]. These studies highlight the importance of understanding the basic mechanisms underpinning the development of dementia, and the various steps down the slippery steps that may need reinforcement for preventive strategies. The most revealing strategies have been imaging to define the disease, genetics to identify minor variants of the genome that undergo linkage disequilibrium, and genomic and proteomic strategies to identify changes in the disease. The three major FAD mutations have been followed by extensive efforts at identifying loci linked to AD and other neurodegenerative diseases, and have identified a large crop of genes associated with various diseases. They also show that several gene variants may be associated independently with multiple degenerative diseases. Interestingly, while APP, PS1 and PS2 are all linked to Aβ production, few variants are consistently linked to Aβ degradation. However, we have recently discovered that impairment of γ-secretase can paradoxically increase Aβ yield by skirting Aβ degrading pathways [45]. We hence need to determine whether mutations in PS1 and APP that presumably impair γ-secretase activity [13] can also operate via this mechanism. Interestingly, proteomic strategies have revealed that there are several proteins that accumulate in AD along with Aβ and MAPT, indicating that the disease represents failure of protein homeostasis [46].

4. APOE AND SELECTED RISK FACTORS AFFECTING AMYLOIDOSIS

Since the start of the Human Genome Project, there have been a number of GWAS studies that have identified several genetic risk factors associated with AD [37]. A major AD risk factor identified by genome wide association studies is ApoE-ε4, which is strongly associated with typical late onset forms of AD, but with low penetrance [47–49]. ApoE within the brain is produced by glial cells [50], and normally maintains brain cholesterol and triglyceride homeostasis, and in the periphery and has been linked to familial hypercholesterolemia syndromes. ApoE is additionally the major cholesterol transporter within the brain and appears to drive AD by multiple mechanisms that, as discussed below, includes reduced Aβ degradation [47, 51]. ApoE exists as a combination of three different isoforms, ε2, ε3, and ε4, wherein ε4 increases AD risk in a dose-dependent manner and ε2 provides some protection against the disease risk introduced by presence of an ε4 allele [52]. Brain imaging studies utilizing the Pittsburgh compound B show that in comparison to ApoE4-ε4-negative subjects, cognitively normal middle-aged subjects carrying the ApoE-ε4 allele have a far greater likelihood of having a higher cerebral amyloid load [43, 53] and, consequently, lower levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 [53]. Studies show that ApoE-ε4, which also promotes premature atherosclerosis, is significantly less frequent in centenarians than in controls, whereas the ApoE-ε2 allele that has been associated with type III and IV hyperlipidemia is significantly increased in this extremely long-lived group [54]. However, ApoE-ε4 as a risk factor in human disease is complex, as it appears to protect carriers against development of age-related macular degeneration, a condition that is associated with amyloid deposition in subretinal pigmented epithelium deposits known as drusen [55]. Several theories are built around ApoE-ε4, such as the failure of CNS cholesterol homeostasis, promoting plaque formation by chaperoning Aβ deposition, reduced Aβ degrading capacity, incorporation into plaques as fragments, promoting APP degradation affecting neuronal survival to ultimately cause AD-related neurodegeneration [56–58]. There is also evidence that ApoE facilitates aggregation and polymerization of Aβ into amyloid fibrils, a process that is less efficiently carried out by the ApoE-ε4 allele [59–63].

Cholesterol is an independent AD risk factor and can foster amyloidosis by stimulation BACE1 processing of APP[64]. Thus cholesterol transport may be another mechanism for ApoE-driven amyloidosis [47]. It is interesting that HMGCR, a cholesterol synthesis gene, has variants that act as genetic modifiers that reduce AD risk of ApoE-ε4 [48]. In addition to cholesterol, HMGCR also mediates synthesis of isoprenoids that regulate several small GTPases such as rho and ras, and these, in turn, regulate Aβ biogenesis [65]. It is reported that ApoE receptors, LRP, and α2-macroglobulin, are involved in the internalization of APP and Aβ generation, and degradation [66, 67], because ApoE binds Aβ and APP [68, 69]. Once internalized and associated with the recycling pathways, ApoE-ε3 more efficiently promotes Aβ lysosomal trafficking and degradation than does ApoE-ε4 [60]. These data point to rapid endocytic trafficking of Aβ-containing vesicles in the presence of ApoE resulting from an increase in efficiency of the recycling of Rab7 from lysosomes to early endosomes. Thus, ApoE-induced intracellular Aβ degradation appears to be mediated by the cholesterol efflux function of ApoE, which lowers cellular cholesterol levels and simultaneously facilitates the intracellular trafficking of Aβ to lysosomes for degradation [63]. It is, however, important to note that the degradation pathway for Aβ in lysosomes has not yet been worked out. In fact, our laboratory found that inhibition of the aspartyl-, serine- and thiol- protease pathways was not sufficient to efficiently block Aβ degradation in lysosomes, suggesting that other novel pathways may be involved in its turnover.

5. CELLULAR MAINTENANCE AND Aβ REGULATION

The role of Aβ degradation takes on a new importance based on our group’s recent findings that Aβ production and degradation may be coupled. Specifically, partial inhibition of γ-secretase, the final step in Aβ production, paradoxically increases Aβ production by circumventing one or more Aβ degradation pathways [45]. However, only a few of the multiple redundant pathways that degrade Aβ have been carefully studied [70–72]. The purpose of this review is to highlight the known and proposed Aβ degrading pathways to provide a foundation for further research in this important area. Two of the major pathways that mediate cellular proteolysis involve the proteasome and the lysosome. The two systems maintain cellular homeostasis by digesting multiple classes of proteins, including faulty or misfolded proteins with different lifespans, and play an important role in orchestrating protein concentrations inside the cell [73–75]. Other widely recognized pathways are cytosolic neutral proteolytic pathways linked to cellular injury and programmed death. In the first pathway, a family of Ca++-activated cysteine proteases named calpains is induced during cellular injury. Secondly, another group of cystolic cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases (caspases) are activated by rapid posttranslational mechanisms and trigger a cascade of events that are characteristic of programmed cell death or apoptosis [76]. The role of these pathways in Aβ turnover is beginning to be uncovered, as described below.

5.1. Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) has Function in SP and NFT Formation

The proteasome is a constitutive multi-catalytic, multi-subunit protease complex that utilizes homopolymers of ubiquitin as a signal to target proteins for degradation in an ATP-dependent pathway[71, 77–79]. In mammals, the most common form is the 26S proteasome (~2 million Da) containing a proteolytic 20S core subunit flanked by two 19S regulatory subunits. The protease complex core is hollow, which provides an opening for proteins to enter and become degraded. First, ubiquitin is adenylylated by the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme and subsequently transferred to the active-site cysteine of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme - E2. In the final step, a family of ubiquitin ligases - E3 -identifies specific targets and catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target protein [80]. A target protein must be labeled by at least 4 ubiquitin molecules before it becomes recognized for proteolysis. Although Aβ is not directed ubiquitinated other proteins involved in its degradation participate in this pathway. NFT’s are also heavily ubiquitinated [81]. The rate of turnover of an individual protein is determined by the amino acid at its N-terminus -termed the ‘N-end’ rule [79, 82, 83]. Although cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins are primary targets of proteasome-mediated degradation, there are other proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the secretory pathway that can also be degraded [84]. Unfolded proteins that translocate to the ER can be degraded by ER-associated degradation (ERAD), which acts as a quality control system and is an essential component of the secretory pathway that tags ER proteins for degradation. ERAD substrates are ultimately transported to the cytosol where they can be more easily accessed by the proteasome [85]. Interestingly, proteins that escape degradation and accumulate in the cytosol can form an aggresome, a juxtanuclear inclusion body that remains accessible for removal by autophagy or proteasome-dependent degradation [86, 87]. However, since our understanding of aggresome formation in neurodegenerative diseases is limited, additional studies are required to advance our knowledge of its underlying molecular mechanisms.

A number of studies have implicated impairment of UPS and proteasome-dependent degradation in neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and Parkinson’s disease (PD). The role of the proteasome in AD has been previously reviewed and is therefore outside the scope of this article [88]. UPS dysfunction leads to the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, as seen in several neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, PD and Huntington’s disease (HD) [89]. Ubiquitin immunohistochemistry detects conjugates in NFTs, dystrophic neurites in SPs, lysosomes, endosomes, and a variety of inclusion bodies and degenerative fibers making it a nearly universal label in protein accumulation diseases [90, 91]. In AD, it appears that the ubiquitin-related pathways are involved in the development of abnormal neuritic processes and NFTs rather than Aβ accumulation [81, 92]. Pharmacological inhibition of the proteasome is sufficient to induce neurodegeneration and cell death [93–95], demonstrating its importance in cellular homeostasis. It has been reported that proteasome inhibition increases APP processing at the γ-secretase site and elevates levels of Aβ in a human neuroblastoma - SH-SY5Y - cell line [83, 96]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that Aβ and MAPT inhibit proteasome activity [97, 98]. However, despite the ability of Aβ40 to inhibit the proteasome, it does not appear to be a substrate of the UPS [98]. The proteasome can additionally modulate intracellular concentrations of both PS1 and PS2, which may indirectly affect γ-secretase activity [99], and provides insights into the complexity of the regulatory system that encompasses the proteasome and key elements of Aβ generation and clearance.

Despite the evidence that implicates impaired UPS function with AD, we are still uncertain about its exact role in aging and neurodegeneration. Even though the proteasome plays a major part in regulating the concentration of proteins while degrading excess or damaged proteins via proteolysis, if the neuron’s metabolic activity becomes compromised and the UPS activity declines, the cell must compensate with redundant pathways to survive. In particular, the role of UPS function in Aβ degradation to prevent its accumulation in the disease state remains to be investigated.

5.2. Lysosomal Processing and its Role in Regulating AD-Associated Proteins

Most extracellular and some cell surface proteins can be internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis and degraded within lysosomes. These organelles contain acid proteases (such as cathepsins B, H, L, and D) and acid hydrolases (such as phosphatases, nucleases, proteases, and glycosidases). Material tagged for degradation is first surrounded by a phagophore-formation and then wrapped into double membrane vesicles called autophagosomes, which then can fuse with late endosomes to form an amphisome. Some cytosolic proteins are degraded after being engulfed in autophagic vacuoles that fuse with lysosomes for removal [100–103].

Previous reports have shown that endosomes and autophagic vacuoles accumulate in the brains of both AD patients and APP-transgenic mice, and that they co-localize intimately with the γ-secretase complex, APP, and CTFβ [104]. Other studies also observe the accumulation of endosomes and present evidence to indicate that it may be a consequence of impaired lysosomal proteolysis [102]. These data suggest that endosomes maybe one of the generation sites for Aβ as inhibiting the C-subunit of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase with bafilomycin, a macrolide antibiotic that inhibits vesicular acidification, leads to intracellular accumulation of both APP and CTFs within the cell [105–108]. This may be due to the processing of APP to CTFβ by BACE1, an aspartyl protease with an acid pH optimum, in an endosome where γ-secretase is also present and converts CTFβ to Aβ [25, 45]. As inhibition of lysosomal acidification will inhibit Aβ production and, thereby, prevent us from evaluating its degradation, one cannot use this approach to determine whether freshly released Aβ is also degraded in the endosome by multiple proteases to limit its yield in the medium.

Impaired autophagic processes have been described to significantly reduce extracellular Aβ due to the inhibition of Aβ secretion through impaired exocytosis [109]. However, this impairment does not inhibit Aβ that, instead, accumulates within intracellular vesicles. Moreover, autophagy deficiency-induced neurodegeneration is further aggravated by amyloidosis. These, together, have been reported to severely impair memory in an AD mouse model. It has been reported that autophagy directly affects the levels of both intracellular and extracellular Aβ, and that intracellular Aβ severely affects memory function. This bolsters the hypothesis that intracellular Aβ is more pathogenic than soluble Aβ in AD [110–113]. Briefly, loss of Atg7 reduces Aβ yield, as evaluated by ELISA analysis, while immunohistochemistry detected an accumulation of intracellular Aβ.

During the early stages of AD, it has been reported that neurons in vulnerable brain regions, such as the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, respond by increasing their production of lysosomal system components [60]. Aging results in the increased expression and lysosomal localization of aspartyl proteases in cortical and brainstem neurons and changes in the endosomal-lysosomal pathway, which may be related to altered intracellular APP metabolism [114, 115]. It has been reported that much of the γ-secretase activity occurs within the endosome to produce nascent Aβ [116]. An overexpression of Rab5 or Rab7, small GTPases that function in vesicle fusion for early and late endosomes, respectively, significantly accelerates Aβ endocytic trafficking to the lysosomes [117]. A potential role for Rho-GTPase has also been elucidated in TgCRND8, a transgenic mouse model that rapidly deposits human Aβ [118]. However, as this compartment is known to be rich in other acid proteases, nascent Aβ may also undergo degradation at this location. As described later, at least one protease, endothelin-converting enzyme has been implicated in Aβ degradation within this compartment [70, 119]. In addition, cathepsin B has been associated with Aβ degradation and its loss in knockout mice leads to an increase in Aβ and development of neurodegeneration [120–122]. However, others have suggested that cathepsin B is a β-site cleaving enzyme specific for wild type APP in the regulated secretory pathway [123, 124].

6. OTHER PATHWAYS FOR Aβ TURNOVER

In addition to the major protein elimination pathways - proteasomal and lysosomal degradation, cells employ a number of constitutive and regulated proteolytic activities that maintain proteostasis - the integrated pathways that regulate the biogenesis, trafficking, and degradation of proteins to maintain their steady-state levels [125]. There is increasing evidence that deficient clearance rather than increased production of Aβ contributes to its accumulation in late-onset AD [126]. Aside from the typical deposition into blood and CSF, it has also been reported that Aβ deposits along perivascular interstitial fluid drainage channels [127] possibly leading to cervical lymph nodes or other lymphatic pathways (Fig. 2). Consistently, recent reports indicate that Aβ is present in lymph nodes and accumulates with brain amyloid deposition [128]. Lymphatic clearance of Aβ appears to be an overlooked, nevertheless important pathway for Aβ removal, particular in view of the recent GWA studies highlighting the role of several genes involved in trafficking between the brain and lymph nodes. Some of these genes code for protein receptors localizing to brain immune competent cells such as dendritic and microglial cells. Germane to this discussion, these cells participate in Aβ degradation and clearance. Although only a few proteolytic pathways have been implicated in the degradation of Aβ, there are several enzymes possessing a broad specificity that may be degrade Aβ; but the exact identity and role of these enzymes in maintaining Aβ levels needs further investigation [129].

6.1. Insulin-Degrading Enzyme (IDE)

Insulin-degrading enzyme is a zinc-endopeptidase located in the cytosol, peroxisomes, and at the cell surface that can cleave a variety of small peptides. These include insulin, glucagon, and insulin-like growth factors I and II, and IDE also converts β-endorphin to γ-endorphin [130, 131]. Interestingly, the enzyme does not contain an obvious signal sequence and is mostly intracellular, yet reports suggest that IDE, in neurons, may be membrane-associated and even secreted into the medium [132, 133]. However, it remains unclear whether IDE is secreted or simply released from damaged cells. IDE appears to participate in both insulin and Aβ catabolism and its levels are reported to be increased in the hippocampus of AD patients [134]. However, the extent to which IDE mediates these processes in vivo has been questioned as the protein is predominantly cytoplasmic and lacks a signal sequence [59]. When the IDE gene was selectively deleted in a hybrid transgenic mouse, it presented key hallmark phenotypic characteristics of AD, including a chronic elevation of cerebral Aβ. The IDE knock-out animals showed a significant 64% increase in brain levels of Aβ X-40 over their wild type littermates [135, 136]. Using Western blotting and in-situ hybridization, it was reported that there was an inverse relationship between IDE expression and age, suggesting that loss of this activity may play a role in the development of AD pathology [137].

Although it is predominantly a cytosolic protease, IDE activity is detected in the medium where it can also degrade secreted Aβ [138]. It has been reported to be the primary soluble Aβ degrading enzyme at neutral pH within the human brain [139]. In a study where chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with APP were treated with conditioned medium of BV-2 microglial cells expressing IDE, there were decreased levels of monomeric, but not oligomeric, Aβ40 and Aβ42 secreted into the medium [140]. Interestingly, Aβ40 and Aβ42 regulate IDE levels via a feedback mechanism, suggesting that cells may attempt to regulate IDE expression to eliminate these toxic peptides [141]. Studies within our laboratory have provided evidence that CTFγ is, likewise, degraded by IDE in a dose-dependent manner and at multiple cleavage sites, which is consistent with its role in the removal of multiple APP-derived γ-secretase cleavage products [136, 142]. A careful analysis of its in vivo function is essential to determine the true contribution of IDE in Aβ accumulation and AD-associated neurodegeneration. It is also important to understand the mechanisms by which IDE is released into the extracellular space where it can degrade Aβ.

6.2. Neprilysin (NEP)

Neprilysin (a.k.a. neutral endopeptidase 24.11 or enkephalinase) is a membrane-bound zinc endopeptidase that is synthesized in the Golgi and transported to the cell surface where its ectodomain is shed into the extracellular space. Although there are four splice variants of the 24 exon NEP gene, their protein-coding region remains constant and codes for a single 750 aa polypeptide (NCBI Accn # NP_009220). Analysis of the NEP sequence by PSORT [143] reveals a type 2 integral-membrane protein structure that starts with a short 31 aa cytoplasmic domain and has a single transmembrane domain (residues 31–47) that serves as a signal and anchor followed by a long extracellular domain that constitutes its catalytically active domain. Some known substrates of the enzyme are shown in Table 1. NEP is a part of a group of vasoendopeptidases that include endothelin-converting enzyme and angiotensin converting enzyme, which are key drug targets for the control of hypertension. NEP is expressed in several tissues, most notably the brain, but is also abundant within the kidney and the lung. NEP is a neutral metalloendopeptidase that is inhibited by phosphoramidon, a natural compound derived from Streptomyces tanashiensis, and thiorphan, an active metabolite of Rececadotril, an anti-diarrheal agent. In a pioneering study, Iwata et al. (2000) evaluated the catabolism of injected radiolabeled synthetic Aβ in the rat hippocampus and discovered that the yield of residual peptide increased significantly in the presence of thiorphan, an inhibitor of NEP [144]. In accord with this, NEP gene disruption showed a gene dose-dependent elevation of endogenous levels of Aβ in the mouse brain [145]. These data suggest that dysregulation of NEP activity may have profound effects on AD pathogenesis and progression by promoting Aβ deposition. The role of NEP in AD is further supported by a decline in NEP in the AD brain, particularly in vulnerable regions such as the hippocampus and the midtemporal gyrus [146], associated with an increase in deposition of Aβ [147]. However, in the striatum, a brain region where Aβ does not typically accumulate, NEP levels appear to increase with age [148]. Interestingly, NEP levels appear to be reduced in the brain of cerebral amyloid angiopathy subjects but are increased in the AD brain [149, 150]. Presynaptic NEP has also been demonstrated to degrade Aβ efficiently and to retard development of amyloid pathology [151]. Further, amyloid plaques have been described that were co-localized with reactive astrocytes expressing high levels of NEP [151]. NEP is therefore a promising candidate protease that accounts for the degradation of secreted Aβ, and mechanisms that maintain its activity in the aging brain are important to investigate. However, as the size of the catalytic subunit of the enzyme is estimated to be smaller than an Aβ monomer, an important area of inquiry that requires more detailed examination relates to the mechanisms by which the enzyme accommodates this large substrate [152]. The role of Neprilysin-2, a soluble and secreted endopeptidase related to NEP, is another unexplored area in the field.

Table 1.

List of known Aβ degrading enzymes with their major substrates.

| Enzyme Name | Substrate | Levels/Activity in AD Brain vs. Control | Metal - Binding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neprilysin | Aβ, Bradykinin, Substance P, Angiotensin-I, Angiotensin-II, Endothelin-1, Kinins, Adrenomedullin, Opioid peptides, enkephalin, gastrin | Increased Reduced |

Zinc | [150, 149] |

| Endothelin-converting enzymes (ECE) | Aβ, Endothelin, substance P, bradykinin, angiotensin I, neurotensin, somatostatin | ECE-1 (no change), ECE-2 (reduced) | Zinc | [158, 157] |

| Insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) | Aβ, Insulin, atrial natriuretic peptide, insulin-like growth factor II, transforming growth factor-α, β-endorphin, amylin, glucagon | Increased Reduced |

Zinc | [134, 139, 149] |

| Angiontensin-converting enzyme (ACE) | Aβ, Angiotensin I, Bradykinin | Increase | Zinc | [163–165] |

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) - primarily MMP-2, MMP-3 and MMP-9 | Aβ, collagen proteins, gelatin | Increase activity | Zinc and calcium | [180] |

| Cathepsin B | Aβ, APP | Unknown | Thiol | [121, 122, 124] |

| Plasmin | Aβ, Fibrin, collagenases, fibronectin, thrombospondin, laminin, von willebrand factor | Reduced activity | [170] |

6.3. Endothelin-Converting Enzyme (ECE)

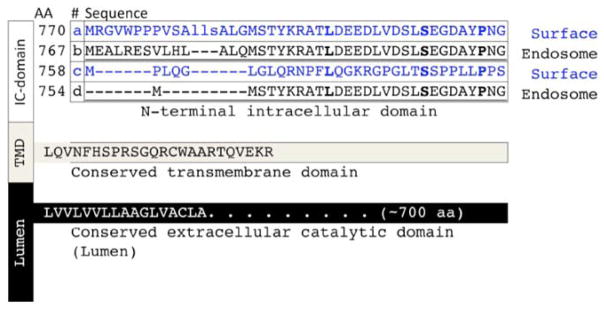

Like NEP, endothelin-converting enzyme is a member of the M13 family of zinc-metalloproteases that processes the inactive big endothelin to its active mature form and, thereby, regulates blood flow [153]. The primary substrates (Table 1) for ECE are big endothelin-1 and -2, which are potent vasoconstrictive peptides produced in vascular endothelial cells. There are two forms of ECE, each having multiple isoforms generated by multiple promoters. ECE-1 is of particular interest, as its isoforms are differentially located at the cell surface and within different intracellular compartments, including endosomes [154]. A homologous enzyme ECE-2 and its isoforms also show similar activities but their localization appears to be exclusively intracellular, including endosomes and the role of its differentially spliced isoforms is not yet established. ECE-1 has four human isoforms (735–770 aa), which are all encoded by a single gene on chromosome 1 (1p36). Each isoform has a unique N-terminal cytoplasmic domain that determines their subcellular localization along with a shared transmembrane domain (Fig. 3). ECE-1 preferentially cleaves at the N-terminal side of its hydrophobic substrates, corresponding to residues Leu17, Val18, and Phe20 of the Aβ peptide [119]. Although NEP and ECE share a similar primary structure, significant differences exist between the two. ECE-1 is a disulfide-linked dimer, whereas NEP is a monomer. As opposed to NEP, ECE-1 is relatively insensitive to thiorphan, but is inhibited by phosphoramidon. A recent study examining the cellular distribution of the ET system in the brain showed the immunohistochemical evidence for the presence of virtually all components of the ET system in 24 regions of the human CNS, including neurons within the cingulate gyrus, hypothalamus, caudate, cerebellum, amygdala, and hippocampus [155]. Therefore, ECE appears to be present within a number of key regions of the brain; thereby, suggesting that this enzyme may be important in AD pathogenesis.

Fig. 3. Sequence variants of endothelin converting enzyme.

ECE-1 is a type-II membrane protein with a variable N-terminal intracellular (IC) domain, and conserved transmembrane (TMD) and extracellular (Lumen) domains [153]. Through multiple alternate promoters, at least four isoforms of ECE-1 have been identified, each with unique intracellular domains that determine subcellular localization and tissue distribution, Isoforms 1a and 1c are primarily localized in the plasma membrane, whereas isoform 1b and 1d are predominantly located in late endosomes/multivesicular bodies and recycling endosomes, respectively [70, 119, 154].

ECE-1 is the best characterized Aβ degrading enzyme, as its activity has been demonstrated in cell cultures and animal models [70]. Interestingly, although they were considered as neutral endopeptidases, the pH optimum of ECE was shown to be substrate dependent with preferential cleavage of Aβ at acid pH, cleaving both Aβ40 and Aβ42 with a strong preference for the former [119]. This finding is consistent with the intracellular degradation of Aβ by ECE-1, which strongly affects the yield of Aβ production, but does not affect the degradation of externally added Aβ into the medium. Moreover, genetic knock down of either ECE-1 or ECE-2 in mice has been reported to significantly increase both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, whereas levels of APP and CTFs remained unchanged [156]. These studies further demonstrate the importance of NEP in Aβ degradation in vivo, as knocking down both enzymes increases Aβ levels more than either enzyme alone. Additionally, genetically knocking out both NEP and ECE yields an additive increase in Aβ within the brain of mice, suggesting that the two enzymes are responsible for regulating two different pools of Aβ. However, it has been reported that there was no change in the levels of ECE-1 in post-mortem AD brain compared to cognitively normal control brain specimens [157], and a reduction in ECE-2 (Table 1), suggesting that the activity is not subject to feedback regulation by Aβ accumulation [158]. This finding is also consistent with the coupled production and degradation of Aβ in the recycling endosome with residual Aβ either being transported to the surface for secretion from the cell or to lysosomes for further degradation.

6.4. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE)

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (aka dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase-1 or DCP-1) is a membrane-bound ectoenzyme that plays an important role in blood pressure and body fluid homeostasis by catalyzing the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, and degrading bradykinin (Table 1), which is a potent vasodilator. Therefore, ACE inhibition has become an effective treatment strategy for hypertension. ACE is secreted in the lung and kidney by cells in the inner layer of blood vessels. Studies on the renin-activating system of mammalian brains may elucidate potential associations between ACE and AD. It has been reported that angiotensin in astrocytes is required for the functional maintenance of the blood-brain barrier [159], which is also impaired in AD. Additionally, ACE inhibits Aβ toxicity in cultured PC12 cells, blocks the aggregation of synthetic Aβ, and cleaves Aβ between the Asp7-Ser8 residues [160, 161].

Although such studies are helpful in elucidating ACE’s activity in relationship to AD, there are data that suggest that ACE is not a direct physiological regulator of steady-state Aβ concentrations in the brain [162]. Following ACE inhibition or genetic disruption, Aβ levels remain unchanged in both soluble and insoluble fractions in vivo[156]. Therefore, despite ACE’s ability to cleave Aβ in vitro, in vivo studies indicate that it does not appear to regulate cerebral amyloidosis. Intriguingly, the level/activity of the enzyme, itself, appears to be increased in AD brains [163–165].

6.5. Plasmin

The serine protease plasmin is derived from the inactive zymogen plasminogen following cleavage by plasminogen activators, such as tissue plasminogen activator and urokinase plasminogen activator. Plasmin is involved in the degradation of blood plasma proteins, including fibrin and many components of the extracellular matrix. Studies have successfully demonstrated that plasmin degrades both non-aggregated monomeric and aggregated fibrillar Aβ with physiologically relevant efficiency [166]. There is evidence indicating that plasmin activity is reduced in AD human brain homogenates compared to cognitively normal control subjects. However, plasminogen and plasmin protein levels were not significantly altered in the AD brain [167]. Nevertheless, Aβ40 aggregate-induced neurotoxicity in primary rat cortical neuronal cultures can be fully mitigated by plasmin treatment [168]. One group reported that plasmin also increases the processing of human APP preferentially at the α cleavage site and efficiently degrades secreted APP fragments [169, 170]. Plasmin is closely associated with cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains called lipid rafts, a preferred site of Aβ generation [171]. It is therefore likely to reduce Aβ levels at a site close to production.

6.6. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs)

MMPs belong to the family of zinc-dependent enzymes that are synthesized as prepro-peptides and are released into the extracellular space as pro-MMPs. Activation of pro-MMPs involves an initial cleavage of part of the propeptide by a tissue, plasma or bacterial proteinase followed by the final removal of the propeptide by an MMP intermediate or another MMP [172, 173]. After activation, MMPs are able to breakdown extracellular matrix and are essential for embryonic development, tissue resorption and remodeling. Inappropriate expression of MMPs has been associated with a wide range of disorders including cardiovascular diseases [173], asthma [174], and multiple sclerosis [175].

An increase of both MMP expression and CSF levels of the major endogenous inhibitor of MMPs, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP), have been documented in AD patients [176, 177]. In contrast, other studies have compared AD to other neurodegenerative disorders and have found either no change or reduced levels of MMPs and TIMPs within the CSF [178, 179]. One study reported an increase in MMP activity in the hippocampus of post-mortem AD patients [180]. Of the MMPs, specifically MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 have been implicated in Aβ degradation. Although MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 levels are not related to Aβ levels in the frontal cortex of AD [181], various studies have suggested that these three MMPs are stimulated by Aβ [177, 182–184].

MMP-2 cleavage of Aβ40 and Aβ42 has been mapped to the Lys16-Leu17, Leu34-Met35, and Met35-Val36 peptide bonds to generate Aβ fragments that have been detected in vivo [185]. In addition to MMP-2’s ability to degrade exogenous Aβ40 and Aβ42, MMP-2 activator, membrane type 1 MMP, it has been reported to degrade fibrillar amyloid plaques extracted from APP transgenic mice [186]. MMP-3’s ability to degrade Aβ directly is unclear; however, MMP-3 appears able to degrade Aβ indirectly by activating other MMPs, like MMP-9 [182, 187]. It has been demonstrated that MMP-9 cleaves soluble Aβ primarily between Leu34-Met35 and secondarily at the Lys15-leu17, Ala30-Ile31, and Gly37-Gly38, sites that are considered to be important for β-sheet formation [187]. When compared to other degrading proteases, such as ECE, IDE, and NEP, MMP-9 was found to be unique in its ability to degrade Aβ fibrils in vitro and within compact plaques in situ, liberating Aβ fragments 1–20 and 1–30 by cleaving sites within the hairpin loop formation of the β-sheet structure [186, 188]. Nevertheless, more studies are required to confirm and understand the role of this nearly ubiquitous protease family.

CONCLUSION

Typical late onset AD has a prolonged course of development and amyloid deposits accumulate for numerous years before causing dementia. For patients with FAD carrying the highly penetrant dominantly inherited mutations, Aβ production begins 30–60 years prior to the onset of dementia [189–194]. Furthermore, amyloid appears to even deposit twenty or more years before the onset of dementia [189–194]. In this regard, it is of interest that using noninvasive amyloid plaque and NFT imaging technologies combined with family history and APOE genotypes, one can identify individuals at risk for developing AD. This is important for recruitment of subjects for clinical trials and for individual planning to confront this devastating disease. A number of clinical trials strongly suggest that late treatment of AD to eliminate Aβ is ineffective in restoring patients after dementia is detected, indicating that blocking the initial step to the complex process leading to AD late during the disease course is insufficient when the nervous system has already undergone degeneration. Furthermore, Aβ-induced initiation of MAPT phosphorylation and neuroinflammation over a decade prior to the development of dementia likely instigates self-sustaining cycles that drives ‘clinically silent’ disease towards the development of clinically observable MCI and AD, and, once initiated, such cycles will be little impacted by later treatments focused on Aβ removal [195]. Despite this, a number of opportunities for prevention or early preclinical intervention remain feasible [3]. As discussed earlier, the ApoE genotype and molecular imaging of SP and NFT has converged to identify individuals at high risk of developing AD, making it particularly important to identify paradigms for AD prevention. It has been reported that that AD patients suffer from poor Aβ clearance [126], suggesting that reducing Aβ production early in the development of pathology may be protective. The best-developed paradigm for potentially reducing Aβ has been the development and use of γ-secretase inhibitors. However, others and we have previously proposed that, contrary to one of the predictions of the amyloid hypothesis, AD may be caused by γ-secretase inhibition [23, 24, 196]. Nevertheless, our recent findings that partial γ-secretase inhibition paradoxically increases Aβ by a mechanism that bypassed Aβ degradation reconciles the two theories [45]. This study also indicates that ECE is a major Aβ-degrading pathway, but there are additional unidentified Aβ degrading pathways in the cell that need to be characterized. In addition, there are proteins other than Aβ and MAPT that accumulate in the AD brain indicating that there is a more generalized failure of protein homeostasis that needs to be addressed [46]. The major constitutive protein degradation systems include the lysosomal pathway, the proteasome and membrane-associated neutral endopeptidases such as matrix metalloproteases. Intramembrane proteolysis by γ-secretase is a recent addition to this rather small list of pathways. Efficient degradation of Aβ is critical to maintain low levels and to avoid accumulation of homo-polymers that form spontaneously. Yet the pathways for Aβ degradation have not been systematically evaluated. This review summarizes the current state of knowledge on Aβ degradation and highlights the key lacunae that need to be filled in order to understand the role of this pathway in preventing SP biogenesis.

The major pathways demonstrated to be involved in degrading Aβ are ECE, NEP, IDE, Cathepsin B, plasmin and MMP. ECE and NEP are membrane proteases that are tissue and brain region specific in their relative distribution. IDE is a cytosolic enzyme but is secreted by an unknown mechanism and is a potent Aβ degrading enzyme. Cathepsin B is an endosomal-lysosomal protease, which has been identified as a β-secretase that can generate Aβ, but knockout mouse studies suggest that it is an Aβ-degrading enzyme. Although convincing genetic variant association has not been demonstrated in humans for these activities with the exception of IDE, mice lacking these enzymes show increases in amyloid accumulation. ECE is the only enzyme whose inhibition acutely increases Aβ production in cell cultures suggesting that the Aβ degradation is actually coupled to production in the endosome. However, we have recently published data showing that γ-secretase inhibition allows Aβ to bypass degradation by multiple activities in the endosomal pathway [45]. Since inhibition of lysosomal proteolysis using known inhibitors does not increase yield of Aβ, we propose that there are novel lysosomal proteases that degrade Aβ that need to be identified. Understanding the clearance pathways will allow us to determine whether and how this mechanism is impaired in AD. Moreover, the degradation pathways may offer targets that can be stimulated to prevent amyloidosis. This type of approach may have advantages over inhibiting critical multifunctional enzymes in the Aβ biogenesis pathways. Therefore, additional research is needed on Aβ degrading enzymes as well as on the earliest events in amyloid accumulation in addition to identifying the steps that lead from Aβ to neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Alzheimer’s Association IIRG 10-173-180 and NIH AG022103 to KS, Alzheimer’s Association IIRG-11-206418 and NIH AG042804 to DKL and Intramural NIA to NHG supported this work. KLB was supported by an MSTP grant - NIH T32 GM08716-13. The authors thank Ms. Meera Parasuraman for reading and editing the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- Aβ

Amyloid-β proteins

- Aβ40

Aβ of 40 aa

- Aβ42

Aβ of 42 aa

- ACE

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM 10

Adamalysin10

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- ApoE-ε4

ApoE ε4 allele

- APP

Aβ precursor protein

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme

- CERAD

Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease

- CTFβ

APP Carboxy terminal fragment of 99 aa

- CTFa

APP Carboxy terminal fragment of 83 aa

- DCP-1

Dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase-1

- ECE

Endothelin-converting Enzyme

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

ER-associated degradation

- FAD

Familial AD

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- IDE

Insulin-degrading Enzyme

- MAPT

Microtubule-associated protein tau

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- NEP

Neprilysin

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangles

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PS1

Presenilin-1

- PS2

Presenilin-2

- SP

Senile plaques

- TIMP

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

- UPS

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Thies W, Bleiler L, Alzheimer’s A. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dem. 2013;9(2):208–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahiri DK, Farlow MR, Sambamurti K, Greig NH, Giacobini E, Schneider LS. A critical analysis of new molecular targets and strategies for drug developments in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2003;4(2):97–112. doi: 10.2174/1389450033346957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker RE, Greig NH. A new regulatory road-map for Alzheimer’s disease drug development. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11(3):215–20. doi: 10.2174/156720501103140329210642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahiri DK, Zawia NH, Greig NH, Sambamurti K, Maloney B. Early-life events may trigger biochemical pathways for Alzheimer’s disease: the “LEARn” model. Biogerontology. 2008;9(6):375–9. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wozniak MA, Frost AL, Itzhaki RF. The helicase-primase inhibitor BAY 57-1293 reduces the Alzheimer’s disease-related molecules induced by herpes simplex virus type 1. Antiviral Res. 2013;99(3):401–4. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nash R, Tokiwa G, Anand S, Erickson K, Futcher AB. The WHI1+ gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tethers cell division to cell size and is a cyclin homolog. EMBO J. 1988;7(13):4335–46. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42(3 Pt 1):631–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2011;10(9):698–712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HG, Zhu X, Castellani RJ, Nunomura A, Perry G, Smith MA. Amyloid-beta in Alzheimer disease: the null versus the alternate hypotheses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321(3):823–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.114009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lahiri DK, Sambamurti K, Bennett DA. Apolipoprotein gene and its interaction with the environmentally driven risk factors: molecular, genetic and epidemiological studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(5):651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambamurti K, Greig NH, Utsuki T, Barnwell EL, Sharma E, Mazell C, et al. Targets for AD treatment: conflicting messages from gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Neurochem. 2011;117(3):359–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pappolla MA, Omar RA, Sambamurti K, Anderson JP, Robakis NK. The genesis of the senile plaque. Further evidence in support of its neuronal origin. Am J Pathol. 1992;141(5):1151–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robakis NK, Pappolla MA. Oxygen-free radicals and amyloidosis in Alzheimer’s disease: is there a connection? Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15(4):457–9. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90077-9. discussion 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1991;349(6311):704–6. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bali J, Halima SB, Felmy B, Goodger Z, Zurbriggen S, Rajendran L. Cellular basis of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Ind Acad Neurol. 2010;13(2):S89–93. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.74251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh DM, Hartley DM, Condron MM, Selkoe DJ, Teplow DB. In vitro studies of amyloid beta-protein fibril assembly and toxicity provide clues to the aetiology of Flemish variant (Ala692-->Gly) Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem J. 2001;355(Pt 3):869–77. doi: 10.1042/bj3550869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochem Intern. 2002;41(5):345–52. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Bjornsson S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488(7409):96–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Younkin SG. The role of A beta 42 in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of physiology, Paris. 1998;92(3–4):289–92. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Kao SY, Lee FJ, Song W, Jin LW, Yankner BA. Dopamine-dependent neurotoxicity of alpha-synuclein: a mechanism for selective neurodegeneration in Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 2002;8(6):600–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambamurti K, Greig NH, Utsuki T, Barnwell EL, Sharma E, Mazell C, et al. Targets for AD treatment: conflicting messages from gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Neurochem. 2011;117(3):359–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambamurti K, Suram A, Venugopal C, Prakasam A, Zhou Y, Lahiri DK, et al. A partial failure of membrane protein turnover may cause Alzheimer’s disease: a new hypothesis. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3(1):81–90. doi: 10.2174/156720506775697142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, et al. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286(5440):735–41. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gandhi S, Refolo LM, Sambamurti K. Amyloid precursor protein compartmentalization restricts beta-amyloid production: therapeutic targets based on BACE compartmentalization. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;24(1):137–43. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:1:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hook VY. Protease pathways in peptide neurotransmission and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26(4–6):449–69. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hook VY, Toneff T, Aaron W, Yasothornsrikul S, Bundey R, Reisine T. Beta-amyloid peptide in regulated secretory vesicles of chromaffin cells: evidence for multiple cysteine proteolytic activities in distinct pathways for beta-secretase activity in chromaffin vesicles. J Neurochem. 2002;81(2):237–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Refolo LM, Sambamurti K, Efthimiopoulos S, Pappolla MA, Robakis NK. Evidence that secretase cleavage of cell surface Alzheimer amyloid precursor occurs after normal endocytic internalization. J Neurosci Res. 1995;40(5):694–706. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambamurti K, Shioi J, Anderson JP, Pappolla MA, Robakis NK. Evidence for intracellular cleavage of the Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 1992;33(2):319–29. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambamurti K, Refolo LM, Shioi J, Pappolla MA, Robakis NK. The Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor is cleaved intracellularly in the trans-Golgi network or in a post-Golgi compartment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;674:118–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent B, Checler F. alpha-Secretase in Alzheimer’s disease and beyond: mechanistic, regulation and function in the shedding of membrane proteins. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(2):140–56. doi: 10.2174/156720512799361646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambamurti K, Greig NH, Lahiri DK. Advances in the cellular and molecular biology of the beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2002;1(1):1–31. doi: 10.1385/NMM:1:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manczak M, Reddy PH. Abnormal interaction of oligomeric amyloid-beta with phosphorylated tau: implications to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal damage. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36(2):285–95. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maloney B, Sambamurti K, Zawia N, Lahiri DK. Applying epigenetics to Alzheimer’s disease via the latent early-life associated regulation (LEARn) model. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(5):589–99. doi: 10.2174/156720512800617955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahiri DK. Prions: a piece of the puzzle? Science. 2012;337(6099):1172. doi: 10.1126/science.337.6099.1172-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy J. Toward Alzheimer therapies based on genetic knowledge. Ann Rev Med. 2004;55:15–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raux G, Guyant-Marechal L, Martin C, Bou J, Penet C, Brice A, et al. Molecular diagnosis of autosomal dominant early onset Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Journal of medical genetics. 2005;42(10):793–5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castellani RJ, Lee HG, Siedlak SL, Nunomura A, Hayashi T, Nakamura M, et al. Reexamining Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a protective role for amyloid-beta protein precursor and amyloid-beta. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(2):447–52. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiman EM. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: advances in 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiman EM, Quiroz YT, Fleisher AS, Chen K, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, et al. Brain imaging and fluid biomarker analysis in young adults at genetic risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in the presenilin 1 E280A kindred: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(12):1048–56. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70228-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleisher AS, Chen K, Quiroz YT, Jakimovich LJ, Gomez MG, Langois CM, et al. Florbetapir PET analysis of amyloid-beta deposition in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease kindred: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(12):1057–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, Bandy D, Yu M, Lee W, et al. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(16):6820–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gandy S. Alzheimer’s disease: new data highlight nonneuronal cell types and the necessity for presymptomatic prevention strategies. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(7):553–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnwell E, Padmaraju V, Baranello R, Pacheco-Quinto J, Crosson C, Ablonczy Z, et al. Evidence of a Novel Mechanism for Partial gamma-Secretase Inhibition Induced Paradoxical Increase in Secreted Amyloid beta Protein. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bai B, Hales CM, Chen PC, Gozal Y, Dammer EB, Fritz JJ, et al. U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex and RNA splicing alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(41):16562–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310249110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poirier J, Miron J, Picard C, Gormley P, Theroux L, Breitner J, et al. Apolipoprotein E and lipid homeostasis in the etiology and treatment of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(Suppl 2):S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leduc V, De Beaumont L, Theroux L, Dea D, Aisen P, Petersen RC, et al. HMGCR is a genetic modifier for risk, age of onset and MCI conversion to Alzheimer’s disease in a three cohorts study. Molecular psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nalbantoglu J, Gilfix BM, Bertrand P, Robitaille Y, Gauthier S, Rosenblatt DS, et al. Predictive value of apolipoprotein E genotyping in Alzheimer’s disease: results of an autopsy series and an analysis of several combined studies. Ann Neurol. 1994;36(6):889–95. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rigat B, Hubert C, Alhenc-Gelas F, Cambien F, Corvol P, Soubrier F. An insertion/deletion polymorphism in the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene accounting for half the variance of serum enzyme levels. J Clin Investig. 1990;86(4):1343–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI114844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Champagne D, Pearson D, Dea D, Rochford J, Poirier J. The cholesterol-lowering drug probucol increases apolipoprotein E production in the hippocampus of aged rats: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. 2003;121(1):99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E affects the rate of Alzheimer disease expression: beta-amyloid burden is a secondary consequence dependent on APOE genotype and duration of disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53(5):429–37. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(1):122–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schachter F, Faure-Delanef L, Guenot F, Rouger H, Froguel P, Lesueur-Ginot L, et al. Genetic associations with human longevity at the APOE and ACE loci. Nat Genet. 1994;6(1):29–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prakasam A, Venugopal C, Suram A, Pacheco-Quinto J, Zhou Y, Pappolla MA, et al. Amyloid and Neurodegeneration: Alzheimer’s Disease and Retinal Degeneration. In: Banik N, Ray SK, editors. Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology. 3. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 131–64. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crutcher KA, Lilley HN, Anthony SR, Zhou W, Narayanaswami V. Full-length apolipoprotein E protects against the neurotoxicity of an apoE-related peptide. Brain Res. 2010;1306:106–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raber J, Huang Y, Ashford JW. ApoE genotype accounts for the vast majority of AD risk and AD pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(5):641–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poirier J. Apolipoprotein E in animal models of CNS injury and in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17(12):525–30. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, Lane S, Finn MB, et al. apoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid beta peptide clearance from mouse brain. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):4002–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI36663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Kanekiyo T, Shinohara M, Zhang Y, LaDu MJ, Xu H, et al. Differential regulation of amyloid-beta endocytic trafficking and lysosomal degradation by apolipoprotein E isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(53):44593–601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.420224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zlokovic BV. Cerebrovascular transport of Alzheimer’s amyloid beta and apolipoproteins J and E: possible anti-amyloidogenic role of the blood-brain barrier. Life Sci. 1996;59(18):1483–97. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00310-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang Q, Lee CY, Mandrekar S, Wilkinson B, Cramer P, Zelcer N, et al. ApoE promotes the proteolytic degradation of Abeta. Neuron. 2008;58(5):681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee CY, Tse W, Smith JD, Landreth GE. Apolipoprotein E promotes beta-amyloid trafficking and degradation by modulating microglial cholesterol levels. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(3):2032–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Refolo LM, Malester B, LaFrancois J, Bryant-Thomas T, Wang R, Tint GS, et al. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates the Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7(4):321–31. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou Y, Suram A, Venugopal C, Prakasam A, Lin S, Su Y, et al. Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate stimulates gamma-secretase to increase the generation of Abeta and APP-CTFgamma. Faseb J. 2008;22(1):47–54. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8175com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Narita M, Holtzman DM, Schwartz AL, Bu G. Alpha2-macroglobulin complexes with and mediates the endocytosis of beta-amyloid peptide via cell surface low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Neurochem. 1997;69(5):1904–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69051904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ulery PG, Beers J, Mikhailenko I, Tanzi RE, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, et al. Modulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein processing by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). Evidence that LRP contributes to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(10):7410–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holtzman DM, Bales KR, Tenkova T, Fagan AM, Parsadanian M, Sartorius LJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E isoform-dependent amyloid deposition and neuritic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(6):2892–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050004797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kounnas MZ, Moir RD, Rebeck GW, Bush AI, Argraves WS, Tanzi RE, et al. LDL receptor-related protein, a multifunctional ApoE receptor, binds secreted beta-amyloid precursor protein and mediates its degradation. Cell. 1995;82(2):331–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eckman CBaE, E.A. Aβ-degrading enzymes: modulators of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and targets for therapeutic intervention. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2005;33(5):1101–05. doi: 10.1042/BST20051101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nijholt DA, De Kimpe L, Elfrink HL, Hoozemans JJ, Scheper W. Removing protein aggregates: the role of proteolysis in neurodegeneration. Current medicinal chemistry. 2011;18(16):2459–76. doi: 10.2174/092986711795843236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pacheco-Quinto J, Herdt A, Eckman CB, Eckman EA. Endothelin-converting enzymes and related metalloproteases in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(1):S101–10. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gonda DK, Bachmair A, Wunning I, Tobias JW, Lane WS, Varshavsky A. Universality and structure of the N-end rule. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(28):16700–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234(4773):179–86. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway of protein degradation. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 1997;2(1):13–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1020301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harwood SM, Yaqoob MM, Allen DA. Caspase and calpain function in cell death: bridging the gap between apoptosis and necrosis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42(Pt 6):415–31. doi: 10.1258/000456305774538238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hershko A, Leshinsky E, Ganoth D, Heller H. ATP-dependent degradation of ubiquitin-protein conjugates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(6):1619–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, et al. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78(5):761–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lecker SH, Goldberg AL, Mitch WE. Protein degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in normal and disease states. J Am Soc Nephrology : JASN. 2006;17(7):1807–19. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thrower JS, Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M, Pickart CM. Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. EMBO J. 2000;19(1):94–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pappolla MA, Omar RA, Kim KS, Robakis NK. Immunohistochemical evidence of oxidative [corrected] stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(3):621–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.DeMartino GN, Slaughter CA. The proteasome, a novel protease regulated by multiple mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22123–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. EMBO J. 1998;17(24):7151–60. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hampton RY, Sommer T. Finding the will and the way of ERAD substrate retrotranslocation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24(4):460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2008;9(12):944–57. doi: 10.1038/nrm2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kopito RR, Sitia R. Aggresomes and Russell bodies. Symptoms of cellular indigestion? EMBO reports. 2000;1(3):225–31. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kopito RR. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends in cell biology. 2000;10(12):524–30. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Checler F, da Costa CA, Ancolio K, Chevallier N, Lopez-Perez E, Marambaud P. Role of the proteasome in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1502(1):133–8. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McNaught KS, Olanow CW, Halliwell B, Isacson O, Jenner P. Failure of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(8):589–94. doi: 10.1038/35086067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Perry G, Friedman R, Shaw G, Chau V. Ubiquitin is detected in neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaque neurites of Alzheimer disease brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(9):3033–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ihara Y, Morishima-Kawashima M, Nixon R. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagic-lysosomal system in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(8) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manetto V, Perry G, Tabaton M, Mulvihill P, Fried VA, Smith HT, et al. Ubiquitin is associated with abnormal cytoplasmic filaments characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(12):4501–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Heinemeyer W, Fischer M, Krimmer T, Stachon U, Wolf DH. The active sites of the eukaryotic 20 S proteasome and their involvement in subunit precursor processing. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(40):25200–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Qiu JH, Asai A, Chi S, Saito N, Hamada H, Kirino T. Proteasome inhibitors induce cytochrome c-caspase-3-like protease-mediated apoptosis in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20(1):259–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00259.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]