Abstract

Engineering has not only developed in the field of medicine but has also become quite established in the field of dentistry, especially Orthodontics. Finite element analysis (FEA) is a computational procedure to calculate the stress in an element, which performs a model solution. This structural analysis allows the determination of stress resulting from external force, pressure, thermal change, and other factors. This method is extremely useful for indicating mechanical aspects of biomaterials and human tissues that can hardly be measured in vivo. The results obtained can then be studied using visualization software within the finite element method (FEM) to view a variety of parameters, and to fully identify implications of the analysis. This is a review to show the applications of FEM in Orthodontics. It is extremely important to verify what the purpose of the study is in order to correctly apply FEM.

Keywords: Finite element analysis, orthodontics, stress

INTRODUCTION

Whenever load is applied to a structure, deformation of the structure and stresses are generated, which cannot be measured directly. In complex structures such as the stomatognathic system, computational techniques have been used to understand the oral biomechanics aspect. The oral cavity is a complex biomechanical system and most of the research has been performed in vitro. But these tests have hardly provided information about their behavior intraorally.[1]

Orthodontics is gradually changing from an opinion-based practice to an evidence-based practice. In the contemporary period, it is necessary to have a scientific rationale for any treatment modality and the evidence of tissue response to it. The greatest progress lies in perceiving some unifying concepts in the abundant evidence and ideas.[2]

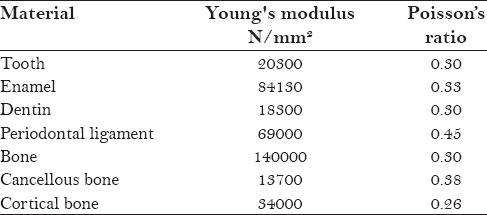

Orthodontic tooth movement takes place when force systems are delivered to the teeth, resulting in different types of displacement in the periodontium. The stress in the periodontal ligament initiates cellular reaction, which results in resorption and apposition of alveolar bone and leads to tooth displacement. Several studies have described the reactions of teeth and their supporting tissues when loaded with an orthodontic force. However, each method of study has its own shortcomings. The most advanced and reliable study is finite element analysis. This is a numeric form of analysis that allows stresses and displacements to be identified. It involves discretization of the continuum (dividing the structure of interest) into a number of elements. There are three basic steps involved: Pre-processing, processing, and post-processing. Pre-processing consists of construction of the geometric model and its conversion finite element, material property data representation, defining the boundary conditions, and loading configuration. Processing includes solving the system of linear algebraic equations. Post-processing consists of interpretation of the results.[3] If we know the mechanical properties of the material, it will be easy to determine the stresses. With FEM, different directed forces applied and stresses which develop, can be calculated. To conduct this experimental method it is interesting to use a resource with anatomical records and modifications in computer aided design (CAD) software so as to build geometrically superior and accurate models. To that purpose, it is necessary to build a virtual model using an image-processing and digital reconstruction software, such as Mimics or Simpleware.[4] In general, regarding the maxillomandibular complex, these reconstructions are carried out through computed tomography (CT) [Figure 1]. CT is mostly obtained with cross-sections of at least 0.25 mm distance to acquire advanced resolution. This is recorded on DICOM format (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) and imported into an image processing and digital reconstruction software [Figure 2]. This is non-invasive procedure with low operating cost and provide information that cannot be obtained by experimental studies.[5] Now days newer and sophisticated programs are available for generating a better model. Many software packages have been developed over the years for various applications like NISA, ANSYS and NASTRAN-PATRAN. In terms of Orthodontics it has resulted in complex tooth periodontium models and model assumptions [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Model image created after CT scan

Figure 2.

Model mesh created

Table 1.

Material parameters used in the finite element model

Studies involving various FEA in orthodontics are:

Williams and Edmundson[6] studied the position of the instantaneous center of rotation (ICR) of a maxillary central incisor using the FEM. It shows that the center of rotation is insensitive to the elastic properties of the PDL. The position of the ICR is independent of load but dependent on the point of loading

Tanne et al.[7] determined principal stresses at the root, alveolar bone, and PDL. Tipping movement produced nonuniform stresses from the cervix to the apex of the root. Translation produced stresses at occlusogingival levels with some difference of the stress from the cervix to the apex

Tanne et al.[8] determined moment to force ratio for the upper right central incisor. The centre of resistance was located at 0.24 times the root length measured from apex to alveolar crest. The centre of rotation varies with moment to force ratio following a hyperbola curve. It was found that even a small difference in the moment to force ratios produced clinically significant changes in the centers of rotation

McGuinness et al.[9] found that the quantification of stress in the PDL is an important concept, as stress in PDL is transmitted to the alveolus with subsequent bone remodeling and tooth movement produced by an edgewise appliance. The maximum stress at the cervical margin of the PDL was 0.072 N/mm2 while the maximum stress induced at the level of the apical foramen was 0.0038 N/mm2. The findings suggested that even with edgewise mechanics, it would be difficult to obtain pure translation or bodily movement

Geramy[10] studied the behavior of initial tooth displacements associated with alveolar bone loss situations when loaded by a force of 1 N. The results revealed that the M/F ratio (at the bracket level) required to produce bodily movement increases in association with alveolar bone loss. Bone loss causes center of resistance movement toward the apex but its relative distance to the alveolar crest decreases at the same time

Rudolph et al.[11] performed FEM analysis to know the displacement and stress distribution of 5 different load systems on a maxillary central incisor. The FEA showed that purely intrusive, extrusive, and rotational forces had stresses concentrated at the apex of the root. The principal stress from a tipping force was located at the alveolar crest. For bodily movement, stress was distributed throughout the PDL; however, it was concentrated more at the alveolar crest

Vasquez et al.[12] evaluated a model using FEM comprising endosseous implant and an upper canine with PDL and cortical and cancellous bone. The initial levels of stress were measured during two types of canine retraction mechanics (friction and frictionless). On the basis of the results, when the anchor unit is an endosseous implant, it seems better to use a recalibrated retraction system without friction (T-loop) where a low load-deflection curve would be generated

Geramy[13] investigated the stress components that appear in the periodontal membrane (PDM), when subjected to transverse and vertical loads equal to 1 N. A further aim was to quantify the alteration in stress that occurs as the alveolar bone is reduced in height by 1 mm, 2.5 mm, 5 mm, 6.5 mm, and 8 mm. The results showed that alveolar bone loss caused increased stress production when compared to healthy bone support. Tipping movements resulted in an increased level of stress at the cervical margin of the PDM in all sampling points and at all stages of alveolar bone loss

Schneider et al.[14] determined the optimal force system for bodily movement of a single-root tooth, with an orthodontic bracket attached using the numerical finite element method (FEM). For different geometries, the ideal M/F ratios that induce a bodily movement were determined. The knowledge of root geometry is important in defining an optimal force system

Zhang et al.[15] studied FEA on a model of six maxillary anterior teeth. Two retractive forces (150 g) were simulated:First, force was used for anterior teeth retraction between the anterior hook of 2 mm and the first molar tube and second simulated anterior tooth retraction by an anterior hook of 4 mm and the implant 10 mm. The first situation showed controlled lingal tipping of the lateral incisor and lingual crown tipping of the central incisors and canines. Stresses were seen at the cervix and root apex of each tooth. In the second situation, central incisors and canines showed lingual crown tipping, whereas the lateral incisors showed bodily retraction and intrusion and also the displacement and stress level were higher

Tominaga et al.[16] studied to determine the optimal height of power arm retraction force and attachment position. A model of bilateral 1st premolar extraction was used. A retractive force of 150 g was applied on to the power arms of height 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 mm from the bracket slot. When the power arm was placed mesial to the canine, at the level of 0 mm (bracket slot level), uncontrolled lingual crown tipping of the incisor was observed and the anterior segment of the archwire was deformed downward. At a power arm height of 5.5 mm, bodily movement was produced and the archwire was less deformed. When the power arm height exceeded 5.5 mm, the anterior segment of the archwire was raised upward and lingual root tipping occurred. When the power arm was placed distal to the canine, lingual crown tipping was observed up to a level of 11.2 mm

Sung et al.[17] constructed model with proclined incisors. The center of resistance was at 9mm superiorly for the 6 anterior teeth and 13.5 mm posteriorly from the midpoint of the labial splinting wire. The working archwires were 0.019 × 0.025-inch or 0.016 × 0.022-inch stainless steel. The anterior retraction hook and compensating curve had less effects on the labial crown torque of the central incisors for en-masse retraction. The 0.016 × 0.022-inch wire showed more tipping of teeth as compared to 0.019 × 0.025-inch archwire. There was no bodily movement of anterior teeth in either archwire when high mini-implant traction and 8-mm anterior retraction hook was considered. Anterior teeth intruded and tipped labially for high mini-implant traction, 2-mm anterior retraction hook, and 100-g midline vertical traction condition

Ansari et al.[3] evaluated the effectiveness of the power arm on the movement of the tooth. The results showed that at the center of resistance and 2 mm above and below it, teeth moved bodily by 0.008 mm. At the center of resistance and 2 mm above and below it, teeth moved bodily by 0.012 mm. At the center of resistance and 2 mm above and below it, teeth moved bodily by 0.013 mm

Padmawar et al.[18] evaluated and compared the stresses generated in the maxillary anterior region during absolute en masse intrusion of six maxillary teeth using mini-implants at two different points of force applications. The study found that use of bilateral implants was more efficient and less detrimental for the teeth during absolute intrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth

Chetan et al.[19] studied maxillary anterior teeth in sagittal and vertical planes during en masse retraction by altering the vertical levels of force application as implant (between second premolar and first permanent molar) at 13.5 mm, 9 mm, and 4.5 mm and also from conventional molar hook in the posterior region. A force of 150 g/side was applied. Results were obtained in relation to two planes––sagittal and vertical. In the sagittal plane, the molar hook level showed lingual tipping of all anterior teeth but the tipping was seen more in canines and least in central incisors. Implant at 4.5 mm also exhibited tipping but was less when compared to the retraction from the molar hook. Similarly, implant at 9 mm and 13.5 mm showed tipping, which was almost the same as that of 4.5 mm. In the vertical plane, molar hook exhibited extrusion of anterior teeth, whereas implant positions showed intrusion

Rokutanda et al.[20] studied to assess the movement pattern of the anterior teeth using power arms and miniimplant. En-masse retraction with sliding mechanics using a force of 250 g parallel to the occlusal plane was applied to the power arm hooks with elastic chains. Authors conclude that the height level of the power arm relative to the level of the centre of resistance may be the most influential factor affecting tooth movement, while power arm length alone has less impact on the subsequent tooth movement. Therefore, it is necessary to calculate an optimal power arm length back from the location of the centre of resistance

Ozaki et al.[21] determined the optimal height of power arm for attaining controlled movement of the anterior teeth in segmented power arm mechanics at a height of 0 mm, 2 mm, 4 mm, 6 mm, 8 mm, 10 mm, and 12 mm from the bracket slot. They found that segmented arch mechanics with power arm can provide higher M/F ratio that is sufficient for controlled anterior tooth movement

Bica et al.[4] evaluated the stress and displacements with the alveolar bone at a height of 0 mm, 2 mm, and 4 mm to which a force of 1N, 3N, and 5N was applied at the center of the clinical height crown. Alveolar bone loss leads to an increase in displacement values. The stress depended on force direction, which increased alveolar bone loss, both on the apical and cervical levels. The loss of alveolar bone lowered the center of tooth resistance and modified the stress distribution at the apex.

LIMITATIONS

FEA result is based on the modeling system. So modeling is a crucial step when performing an FEA study. For this an expert operator is required. Also, one must be aware of material properties, load applied, and boundary condition. Thus, the results must be evaluated with great care.

CONCLUSION

FEM is a reliable experimental analysis that is easy, cost-effective, and takes less time. This field has not only taken orthodontics to new heights but is also used extensively by other fields of dentistry and medicine. The role of FEM in treatment planning, bone remodeling, determining the center of resistance and rotation, and retraction has helped in understanding the biomechanics of tooth movement. Further, newer ideas can be easily implied using FEM.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Piccioni MA, Campos EA, Saad JR, Andrade MF, Galvão MR, Rached AA. Application of the finite element method in dentistry. RSBO. 2013;10:369–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarmah A, Mathur AK, Gupta V, Pai VS, Nandini S. Finite element analysis of dental implant as orthodontic anchorage. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011;12:259–64. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansari TA, Mascarenhas R, Husain A, Salim M. Evaluation of the power arm in bringing about bodily movement using finite element analysis. Orthodontics (Chic.) 2011;12:318–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bica C, Brezeanu L, Bica D, Suciu M. Biomechanical reactions due to orthodontic forces. A finite element study. Procedia Tech. 2015;19:895–900. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamble RH, Lohkare S, Hararey PV, Mundada RD. Stress distribution pattern in a root of maxillary central incisor having various root morphologies: A finite element study. Angle Orthod. 2012;82:799–805. doi: 10.2319/083111-560.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams KR, Edmundson JT. Orthodontic tooth movement analysed by the finite element method. Biomaterials. 1984;5:347–51. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(84)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanne K, Sakuda M, Burstone CJ. Three-dimensional finite element analysis for stress in the periodontal tissue by orthodontic forces. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;92:499–505. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanne K, Koenig HA, Burstone CJ. Moment to force ratios and the center of rotation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;94:426–31. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuinness N, Wilson AN, Jones M, Middleton J, Robertson NR. Stresses induced by edgewise appliances in the periodontal ligament - A finite element study. Angle Orthod. 1992;62:15–22. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1992)062<0015:SIBEAI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geramy A. Initial stress produced in the periodontal membrane by orthodontic loads in the presence of varying loss of alveolar bone: A three-dimensional finite element analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24:21–33. doi: 10.1093/ejo/24.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph DJ, Willes PM, Sameshima GT. A finite element model of apical force distribution from orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:127–31. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0127:AFEMOA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasquez M, Calao E, Becerra F, Ossa J, Enríquez C, Fresneda E. Initial stress differences between sliding and sectional mechanics with an endosseous implant as anchorage: A 3-dimensional finite element analysis. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:247–56. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0247:ISDBSA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geramy A. Alveolar bone resorption and the center of resistance modification (3-D analysis by means of the finite element method) Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117:399–405. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(00)70159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider J, Geiger M, Sander FG. Numerical experiments on long-time orthodontic tooth movement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;121:257–65. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.121007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang DQ, Su JH, Xu LY, Zhong PP. 3D finite element study of En masse retraction of maxillary anterior teeth in two typical force directions. Chin J Dent Res. 2008;11:101–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tominaga JY, Tanaka M, Koga Y, Gonzales C, Kobayashi M, Yoshida N. Optimal loading conditions for controlled movement of anterior teeth in sliding mechanics. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:1102–7. doi: 10.2319/111608-587R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sung SJ, Baik HS, Moon YS, Yu HS, Cho YS. A comparative evaluation of different compensating curves in the lingual and labial techniques using 3D FEM. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:441–50. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padmawar SS, Belludi A, Makhija PG, Bharadwaj A, Virang B. Stress Appraisal with simulation of en masse absolute intrusion of maxillary anteriors deploying strategic mini-implant locations: A finite element Orthod analysis. J Ind Soc. 2012;46:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19.S C, Keluskar KM, Vasisht VN, Revankar S. En-masse retraction of the maxillary anterior teeth by applying force from four different levels - A finite element study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZC26–30. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8408.4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rokutanda H, Koga Y, Yanagida H, Tominaga J, Fujimura Y, Yoshida N. Effect of power arm on anterior tooth movement in sliding mechanics analyzed using a three-dimensional digital model. Orthod Waves. 2015;74:93–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozaki H, Tominaga JY, Hamanaka R, Sumi M, Chiang PC, Tanaka M, et al. Biomechanical aspects of segmented arch mechanics combined with power arm for controlled anterior tooth movement: A three-dimensional finite element study. J Dent Biomech. 2015;6:1758736014566337. doi: 10.1177/1758736014566337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]