Abstract

Bone formation and remodeling occurs throughout life and requires the sustained activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, particularly during periods of rapid bone growth. Despite increasing evidence linking bone cell activity to global energy homeostasis, little is known about the relative energy requirements or substrate utilization of bone cells. In these studies, we measured the uptake and distribution of glucose in the skeleton in vivo using positron-emitting 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]-FDG) and non-invasive, high-resolution positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging and ex vivo autoradiography. Assessment of [18F]-FDG uptake demonstrated that relative to other tissues bone accumulated a significant fraction of the total dose of the glucose analog. Skeletal accumulation was greatest in young mice undergoing the rapid bone formation that characterizes early development. PET/CT imaging revealed that [18F]-FDG uptake was greatest in the epiphyseal and metaphyseal regions of long bones, which accords with the increased osteoblast numbers and activity at this skeletal site. Insulin administration significantly increased skeletal accumulation of [18F]-FDG, while uptake was reduced in mice lacking the insulin receptor specifically in osteoblasts or fed a high-fat diet. Our results indicated that the skeleton is a site of significant glucose uptake and that its consumption by bone cells is subject to regulation by insulin and disturbances in whole-body metabolism.

Introduction

To maintain tissue strength and architecture, the skeleton undergoes a lifelong remodeling process. This task is performed by highly specialized, terminally differentiated cells; osteoclasts that resorb old and damaged bone, and osteoblasts that synthesize new tissue. The production of this new collagen-rich matrix and its subsequent mineralization is expected to require substantial energetic input 1 and as a result the osteoblastic differentiation program is associated with the accumulation of a large number of high transmembrane-potential mitochondria to fulfill energy demands.2–4 Furthermore, recent assessments of bone cell bioenergetics indicate that osteoblasts adjust their metabolic programming according to differentiation state-specific fluctuations in energy requirements. Immature, proliferative pre-osteoblasts rely primarily upon glycolysis to generate energy.3,5 As maturation proceeds, osteoblasts engage oxidative phosphorylation to increase the levels of ATP production during matrix deposition and mineralization, before reverting back to glycolysis during terminal differentiation.3,6

To coordinate osteoblast metabolism with whole-body energy expenditure, accumulating evidence has revealed that the skeleton also functions as a dynamic endocrine organ that contributes to metabolic homeostasis.7 Osteocalcin, produced by the mature osteoblast, is now postulated to act as a hormone that contributes to the regulation of glucose homeostasis.8–10 Osteocalcin initiates the activation of a feed-forward bone-pancreas endocrine loop wherein circulating osteocalcin stimulates β-cell proliferation and insulin synthesis,11,12 while insulin, in turn, enhances osteocalcin production and bioavailability.13,14 Genetic evidence points to the existence of still other, unidentified bone-derived hormones that also contribute to metabolic regulation.15

Despite this increasing body of evidence linking bone cell activity to global energy homeostasis, relatively little is known about the energy requirements or substrate usage by bone cells. Early studies utilizing bone slices and then cultures of isolated calvarial cells indicated that the osteoblast is highly glycolytic and the rate of utilization is on par with liver hepatocytes.16–18 Consistent with these findings, osteoblasts express functional glucose transporters (Glut)19,20 and insulin as well as other osteoanabolic agents increase glucose consumption.5,20–23 Likewise, recent genetic evidence suggests that early bone development requires the expression of Glut1.19 The utilization of fatty acids, glutamine, or other macromolecules as energy sources by osteoblasts has not been well studied.24–27

Radiolabeled glucose analogs, including positron-emitting 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]-FDG), can be used to quantify glucose utilization. In a manner analogous to glucose, 2-deoxyglucose and radiolabeled derivatives are imported into cells via a mechanism that involves Glut-mediated transport. Substrates then pass into the first stage of glycolysis and are phosphorylated by hexokinases to form 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate.28,29 Further metabolic conversion is impaired due to its actions as a competitive inhibitor of phosphoglucoisomerase.30 The resulting accumulation of radiolabelled glucose can be exploited to delineate sites of heightened glucose utilization by autoradiograpy or non-invasive and highly sensitive positron emission tomography.29,31 The latter technique is now widely used in clinical nuclear medicine to diagnose and monitor glucose-avid malignancies.

Here we utilized quantitative in vivo imaging and biodistribution studies to examine skeletal glucose uptake during growth and in states of impaired metabolism. We demonstrate that bone exhibits significant [18F]-FDG uptake, especially within the trabecular bone compartment. Unexpectedly, the magnitude of [18F]-FDG accumulation in examined bone tissue exceeds that of classical glucose storage/utilizing organs including the liver, muscle, and white adipose tissue. Moreover, the acquisition of glucose by the skeleton appears to be directly regulated by insulin, as [18F]-FDG uptake was reduced in a genetic model of impaired insulin receptor signaling as well as a model of diet-induced obesity. These data suggest that the metabolic demands of osteoblasts and osteocytes represent a significant component of whole-body energy glucose utilization and disposal.

Materials and methods

Mouse models

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University approved all animal procedures. Male C57BL/6 mice (C57BL/6J, 6, 8, and 12 weeks of age) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and acclimated for at least 2 weeks prior to use. Young, 3-week-old males were acquired from established breeding pairs obtained from the same source. For diet-induced obesity studies, male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks of age) were fed a low fat (D12450J, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or high-fat diet (D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), in which 10 and 60% of calories are derived from fat, for 12 weeks. Body weights were measured weekly. Glucose levels were assessed with a handheld glucometer (OneTouch Ultra, LifeScan, Wayne, PA, USA) after a 6 h fast. Mice lacking the insulin receptor in osteoblasts were previously described.14 In brief, mice containing floxed alleles of the insulin receptor (IRflox/flox, Bruning et al. 32) were crossed with mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of the human osteocalcin promoter (Oc-Cre, Zhang et al.33) in order to delete the insulin receptor in osteoblasts and osteocytes (ΔIR mice). ΔIR mice were used at 12 weeks of age. Insulin was administered via intraperitoneal injection (0.5 units per kg body weight) directly before the biodistribution study.

[18F]-FDG biodistribution

Clinical grade [18F]-FDG was obtained from the Johns Hopkins PET Center Radiopharmacy, supplied by PETNET Solutions (Siemens Healthcare, Malvern, PA, USA). Injectate was assayed using a sodium iodide CRC-15 dose calorimeter and a calibration factor of 439 (Capintec, Ramsey, NJ, USA). Standard [18F]-FDG uptake studies were preformed. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and injected intravenously via the retro-orbital sinus with 100 μCi of tracer diluted to a final volume of 150 μL in isotonic saline. Following a 2 h uptake period under continuous isoflurane anesthesia, animals were killed and tissues were collected. Tissue activity was assessed by gamma-counting, using an energy set ±50 keV from the 511 keV photopeak (Wizard2, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). [18F]-FDG levels were normalized to the weight of resected tissue and expressed as the percent injected dose per gram tissue weight (%ID·g−1).

Small animal positron emission tomography

Mice were injected with [18F]-FDG as described for [18F]-FDG biodistribution. Following a 90 min uptake period under continuous isoflurane anesthesia, mice were imaged on a SuperArgus small-animal integrated PET/CT scanner (Sedecal Systems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Sequential PET (12 min acquisition, 140–700 keV energy window) and CT scans were performed. CT parameters for acquisition were 40 kVp and 0.8 mA with 2 mm aluminum filtration. The three dimensional imaging analysis platform Amira (version 5.0; FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) was used to merge the PET and CT data sets to visualize [18F]-FDG uptake in relation to the skeleton.

Autoradiography

The whole right hind-limb was resected during [18F]-FDG biodistribution. Tissue was incubated at 4 °C for 1 h in optimal cutting temperature media (Fisher Healthcare, Houston, TX, USA). The limb was then transferred to a fresh optimal cutting temperature-filled mold and flash frozen on dry ice. The limb was rapidly sectioned using a custom modified CM1800 cryostat (Leica, Wetzler, Germany) at 10 μm. Standard sensitivity phosphor-screens (PerkinElmer) were exposed to the section in order to visualize [18F]-FDG uptake as needed for digital autoradiography and read using a Cyclone Phosphorimager (PerkinElmer).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Data were subjected to an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test or analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test as appropriate. P-values <0.05 are considered significant.

Results

Skeletal uptake and distribution of [18F]-FDG in mouse bone

To examine glucose uptake by the skeleton and to determine the relative contribution of bone to whole-body glucose homeostasis, we administered the radiolabeled glucose analog [18F]-FDG via retro-orbital injection and performed whole-body biodistribution studies. As indicated above, [18F]-FDG is transported into cells in a manner similar to endogenous glucose but metabolism beyond conversion to [18F]-FDG-6-phosphate by hexokinases is minimal.31,34

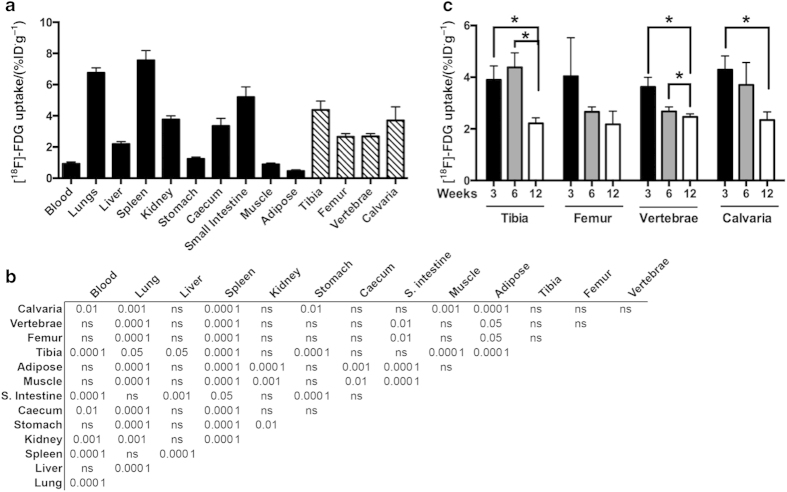

In 6-week-old C57Bl/6 mice, maintained at the plane of anesthesia to reduce variance in uptake due to locomotion, [18F]-FDG uptake by bone ranged from (4.38±0.56)%ID·g−1 in the tibia to (2.65±0.20) % ID·g−1 in the femur (Figure 1a). By comparison, the levels of uptake in classical insulin target and glucose storing tissues including gonadal white adipose tissue (0.45±0.56) % ID·g−1 and the quadriceps (0.89±0.08) % ID·g−1 were significantly lower (P<0.000 1 analysis of variance, Figure 1b). Uptake by the femur and L4–L5 vertebrae (2.67±0.18) % ID·g−1 was similar with that of the liver (2.19±0.15) % ID·g−1. Taken together, these data suggest bone contributes significantly to the clearance of circulating glucose, at least in the steady state.

Figure 1.

Skeletal and whole-body accumulation of [18F]-FDG. (a) Whole-body biodistribution of [18F]-FDG in 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mice following 2 h uptake (10 μCi per mouse). (b) Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests are shown for each tissue pair depicted in a. P-values for the indicated level of significance or not significant (NS) are shown for each pair. (c) [18F]-FDG levels in tibia, femur, L4–L5 vertebrae, and calvaria of 3, 6, and 12 weeks old C57BL/6 male mice. n=4–6 mice per group. *P<0.05.

We next examined whether glucose uptake by bone is altered with age. Cohorts of 3-, 6-, and 12-week-old mice were generated and then analyzed for [18F]-FDG distribution by quantitative γ-counting. In three of the four skeletal sites examined, including the tibia, vertebrae, and calvarium, [18F]-FDG uptake was reduced with increasing age (Figure 1c). The effect of age was most drastic in the tibia and calvaria where uptake at 12 weeks of age was reduced by 43% and 45%, respectively, when compared with 3 weeks of age. [18F]-FDG uptake in the femur followed a similar trend, but did not reach statistical significance.

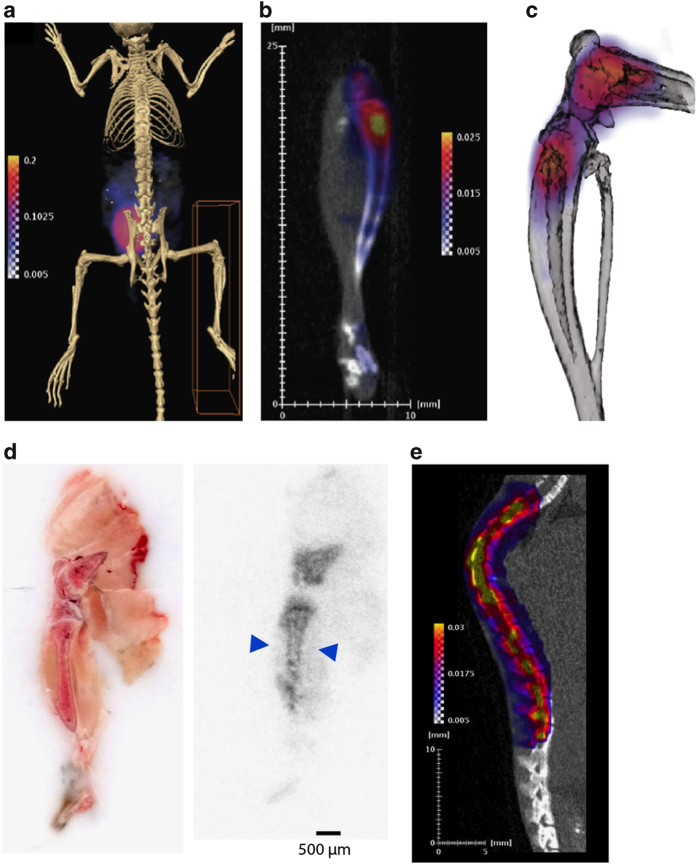

To distinguish the relative uptake of [18F]-FDG by different skeletal envelopes, we localized the [18F]-FDG signal in the cortical and trabecular bone compartments by PET/CT imaging and autoradiography. In whole-body PET/CT scans, the greatest level of [18F]-FDG accumulation was evident in the urinary bladder (Figure 2a), consistent with the primary route of [18F]-FDG clearance.35,36 Closer inspection of the hind limb demonstrated that [18F]-FDG uptake by bone was most prominent in the trabecular bone compartments in the epiphyses and metaphyses of the distal femur and proximal tibia (Figure 2b and c). A similar distribution was evident in rapid, whole-mount hind limb autoradiography studies. This technique also revealed significant uptake by cortical bone (Figure 2d). In the spinal column, [18F]-FDG signal intensity in PET/CT scans corresponded with individual vertebrae (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Localization of [18F]-FDG in bone. (a) Whole-body PET/CT image of 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mouse 2 h after [18F]-FDG administration. (b) [18F]-FDG uptake in the right hind limb of the mouse from a. (c) Computer rendering of PET/CT image of [18F]-FDG uptake of the distal femur and proximal tibia of mouse from a. (d) Whole-mount tissue section of 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mouse hind limb with autoradiograph on the right showing [18F]-FDG uptake in the distal femur and proximal tibia. Arrows denote uptake in the cortical bone compartment. (e) PET/CT image of the spinal column of a 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mouse. Images are representative of five mice. Intensity thresholds map counts per second per voxel.

Reduced skeletal uptake of [18F]-FDG in mouse models of insulin resistance

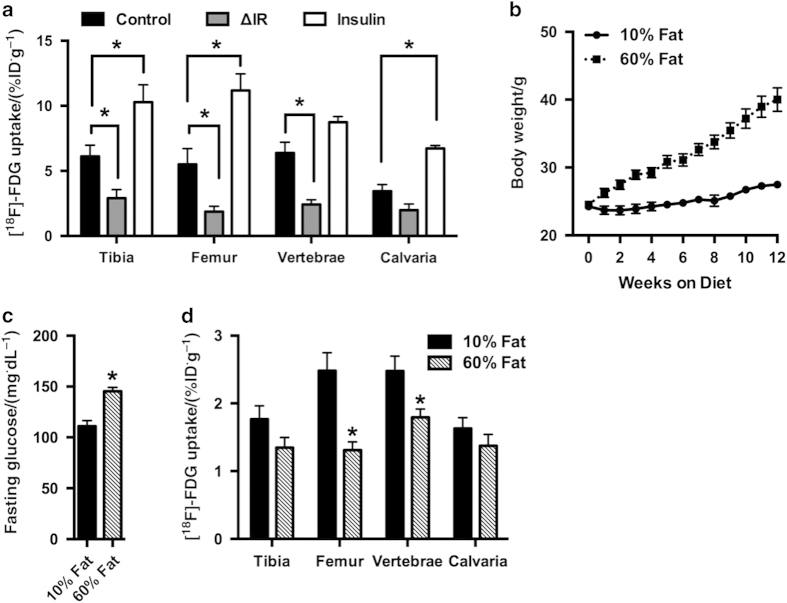

As insulin is the major regulator of glucose disposal from the circulation and is critical for normal post-natal bone development,14 we next queried whether [18F]-FDG uptake by the skeleton is influenced by insulin. For these studies, we generated cohorts of ΔIR mice, in which the insulin receptor has been disrupted specifically in osteoblasts and osteocytes,14 and control littermates. As expected, the loss of insulin receptor expression in osteoblasts significantly reduced [18F]-FDG uptake in the tibia, femur, and vertebrae (Figure 3a). The effect was most severe in the femur where [18F]-FDG uptake was 44% of that in control mice. Residual activity within the bone tissue of ΔIR mice could be the result of uptake by non-osteoblastic cells (such as endothelial cells, marrow cells, osteoclasts, and osteoprogenitors) within bone that are not targeted by the osteocalcin-CRE transgene or due to uptake via insulin-insensitive mechanisms. As these data could be influenced by the overall decrease in trabecular bone volume in ΔIR mice,14 we also preformed the reverse study and treated an additional group of control mice with insulin (0.5 units per kg body weight) immediately prior to [18F]-FDG injection. Consistent with the notion that insulin directly regulates glucose uptake by bone, this manipulation significantly increased [18F]-FDG accumulation in the tibia, femur, and calvaria. [18F]-FDG levels in the femur of insulin treated mice were more than double those in control mice.

Figure 3.

Insulin signaling and high-fat diet feeding influence skeletal accumulation of [18F]-FDG. (a) [18F]-FDG levels in tibia, femur, L4–L5 vertebrae, and calvaria in control, ΔIR, and control mice treated with insulin (0.5 units per kg body weight). n=5–11 mice per group. (b) Body weights of mice fed a high-fat diet (60% fat) or an isocaloric low-fat diet (10% fat). (c) Blood glucose levels after a 6 h fast in mice fed a high or low fat diet for 12 weeks. (d) [18F]-FDG levels in tibia, femur, L4–L5 vertebrae, and calvaria. n=8 mice per diet. *P<0.05.

Finally, we questioned whether diet-induced obesity, which has been reported to trigger the development of insulin resistance in bone,37 alters [18F]-FDG uptake. Cohorts of male C57Bl/6 mice were fed calorically matched low- (10% of calories from fat) and high-fat (60% of calories from fat) diets for 12 weeks and body weights were assessed weekly. In accordance with the development of a state of disturbed metabolism in the mice fed a high-fat diet, body weight increased rapidly (Figure 3b) and was accompanied by fasting hyperglycemia (Figure 3c), when compared with mice fed a low-fat diet. In biodistribution studies, high-fat diet feeding reduced [18F]-FDG uptake in the femur and vertebrae by 47 and 28%, respectively (Figure 3d). A trend for reduced [18F]-FDG uptake was also evident in the tibia. Taken together these data suggest that the regulation of glucose uptake by bone is comparable to that in other more classical glucose storage/utilizing tissues and is similarly influenced by disturbances in whole-body metabolism.

Discussion

Bone formation and remodeling are critical lifelong processes in all mammals. The structure and biological complexity of the dynamic nature of bone is likely to command significant utilization of available energy substrates. In these studies, we utilized the positron-emitting glucose analog [18F]-FDG to examine glucose uptake by the skeleton and to position bone within the physiologic control mechanisms by which glucose homeostasis is maintained. To our knowledge, our data provide the first in vivo evidence that glucose is normally consumed at high levels by bone in an insulin-dependent fashion. Moreover, evaluation of genetically engineered and metabolic disease models demonstrate that glucose acquisition by the skeleton is impaired by global metabolic perturbations associated with high-fat diet feeding.

A striking finding in our study was the relatively large amounts of [18F]-FDG accumulation in the skeleton, which supports the hypothesis that bone makes a significant contribution to overall glucose clearance. For example, in 6-week-old C57Bl/6 mice, the accumulation of [18F]-FDG by the tibia, femur, L4–L5 vertebrae, and calvaria exceeded that of the quadriceps and gonadal white adipose tissue and uptake in two of the four bones were comparable to that of the liver on a per gram tissue basis. In the postprandial state and under the conditions of a euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp, more than 80% of glucose is taken up by skeletal muscle in humans.38 Moreover, genetic disruption of insulin receptor expression in skeletal muscle leads to a redistribution of glucose to other tissues, including fat, in mouse models.39 We eliminated one mechanism by which glucose transport into skeletal muscle is stimulated40 by maintaining mice under anesthesia and thereby minimizing muscle contractions. In addition, the amount of [18F]-FDG administered in our study is unlikely to elicit a significant insulin response. Consequently, the relative levels of [18F]-FDG uptake in each tissue likely represent the baseline levels of glucose acquisition.

Our findings demonstrate that [18F]-FDG uptake by the skeleton is also under the control of insulin and is reduced by high-fat diet feeding. These data accord with a recent report that demonstrated the development of insulin resistance in bone after high-fat diet feeding, and that compromised insulin signaling under these conditions contributed to disturbances in whole-body metabolism.37 Although this study attributed the overall contribution of the skeleton to impairments in osteocalcin activation,37 our studies suggest that deficiencies in glucose uptake by bone may also directly contribute to the development of metabolic impairments. A second study demonstrated that under the conditions of a euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp, glucose uptake in the femur was significantly less responsive to insulin than that of the gastrocnemius.19 Unfortunately, we were unable to compare the relative levels of insulin-stimulated [18F]-FDG uptake in bone with that of muscle due to logistical constraints associated with the short half-life of this glucose analog. Nonetheless it seems evident that bone should now be viewed as a possible organ that contributes to glucose disposal.

The apparent preferential accumulation of [18F]-FDG uptake in the epiphyseal and metaphyseal trabecular bone compartment over that of cortical bone accords with the greater surface area and higher numbers of osteoblasts and rate of (re)modeling at this skeletal site. As indicated above, the protein synthesis required for the preparation of new bone is expected to be the most energetically costly cellular process.1 However, it is interesting that lower levels of [18F]-FDG uptake are still evident in the cortical bone. It is likely that uptake at this site would be increased following an appropriate anabolic signal. Indeed, the activation of enzymes involved in glucose metabolism is among the earliest response associated with increased mechanical loading.41

Our finding of an age-related decline in glucose uptake by the skeleton was expected given the dynamics of bone mass, especially in the C57Bl/6 mouse strain, which is known to have relatively low bone mass among inbred strains.42 However, the rate at which [18F]-FDG was reduced with advancing age is intriguing. Peak trabecular bone volume is achieved between 6 and 8 weeks of age in C57Bl/6 strain and then steadily declines.43 Our data suggest that glucose uptake by the skeleton begins to decline even before peak trabecular bone volume is attained with significant decreases or strong downward trends in [18F]-FDG accumulation evident even between 3- and 6-week-old animals. Although confirmation would require additional study, it seems likely that the age-related decline in [18F]-FDG uptake is due to corresponding decreases in osteoblast numbers. In vitro studies suggest that osteoblasts are highly glycolytic,16–18 and osteoblasts numbers decrease even more rapidly than trabecular bone volume in C57Bl/6 mice.43

In summary, these data indicate that the skeleton is far from metabolically inert and should be considered as a possible site of significant glucose disposal. Quantitative and non-invasive nuclear medicine techniques can be used to provide novel insights into the metabolic requirements of this mineralized tissue. Moreover, glucose uptake by the skeleton appears to respond to the same metabolic cues as other tissues. These data contribute to the growing body of evidence pointing to the skeleton as a major contributor in the regulation of organismal metabolism.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant DK099134 to RCR, Steve Wynn Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation to DLJT and the Johns Hopkins University Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA006973). TLC is supported by a Merit Review Grant (BX001234) and is the recipient of a Senior Research Career Scientist Award from the Veterans Administration.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Buttgereit F , Brand MD . A hierarchy of ATP-consuming processes in mammalian cells. Biochem J 1995; 312 Pt 1: 163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passi-Even L , Gazit D , Bab I . Ontogenesis of ultrastructural features during osteogenic differentiation in diffusion chamber cultures of marrow cells. J Bone Miner Res 1993; 8: 589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova SV , Ataullakhanov FI , Globus RK . Bioenergetics and mitochondrial transmembrane potential during differentiation of cultured osteoblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2000; 279: C1220–C1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BY , Gal I , Hartshtark Z et al. Induction of osteoprogenitor cell differentiation in rat marrow stroma increases mitochondrial retention of rhodamine 123 in stromal cells. J Cell Biochem 1993; 53: 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esen E , Chen J , Karner CM et al. WNT-LRP5 signaling induces Warburg effect through mTORC2 activation during osteoblast differentiation. Cell Metabolism 2013; 17: 745–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntur AR , Le PT , Farber CR et al. Bioenergetics during calvarial osteoblast differentiation reflect strain differences in bone mass. Endocrinology 2014; 155: 1589–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGirolamo DJ , Clemens TL , Kousteni S . The skeleton as an endocrine organ. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012; 8: 674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK , Sowa H , Hinoi E et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 2007; 130: 456–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoch ML , Clemens TL , Riddle RC . New insights into the biology of osteocalcin. Bone 2016; 82: 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty G , Ferron M . The contribution of bone to whole-organism physiology. Nature 2012; 481: 314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M , Hinoi E , Karsenty G et al. Osteocalcin differentially regulates beta cell and adipocyte gene expression and affects the development of metabolic diseases in wild-type mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 5266–5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M , McKee MD , Levine RL et al. Intermittent injections of osteocalcin improve glucose metabolism and prevent type 2 diabetes in mice. Bone 2011; 50: 568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M , Wei J , Yoshizawa T et al. Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell 2010; 142: 296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulzele K , Riddle RC , DiGirolamo DJ et al. Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell 2010; 142: 309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y , Kode A , Xu L et al. Genetic evidence points to an osteocalcin-independent influence of osteoblasts on energy metabolism. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26: 2012–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle AB , Nichols N , Nichols G Jr . Metabolic studies of bone in vitro. I. Normal bone. J Biol Chem 1960; 235: 1206–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn DV , Forscher BK . Aerobic metabolism of glucose by bone. J Biol Chem 1962; 237: 615–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck WA , Birge SJ Jr , Fedak SA . Bone Cells: Biochemical and Biological Studies after Enzymatic Isolation. Science 1964; 146: 1476–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J , Shimazu J , Makinistoglu MP et al. Glucose uptake and Runx2 synergize to orchestrate osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 2015; 161: 1576–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM , Rogers SD , Sleeman MW et al. Modulation of glucose transport by parathyroid hormone and insulin in UMR 106-01, a clonal rat osteogenic sarcoma cell line. J Mol Endocrinol 1995; 14: 263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esen E , Lee SY , Wice BM et al. PTH Promotes bone anabolism by stimulating aerobic glycolysis via IGF signaling. J Bone Miner Res 2015; 30: 2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ituarte EA , Halstead LR , Iida-Klein A et al. Glucose transport system in UMR-106-01 osteoblastic osteosarcoma cells: regulation by insulin. Calcif Tissue Int 1989; 45: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoidis E , Ghirlanda-Keller C , Schmid C . Stimulation of glucose transport in osteoblastic cells by parathyroid hormone and insulin-like growth factor I. Mol Cell Biochem 2011; 348: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner CM , Esen E , Okunade AL et al. Increased glutamine catabolism mediates bone anabolism in response to WNT signaling. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 551–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey JL , Li Z , Ellis JM et al. Wnt-Lrp5 signaling regulates fatty acid metabolism in the osteoblast. Mol Cell Biol 2015; 35: 1979–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamek G , Felix R , Guenther HL et al. Fatty acid oxidation in bone tissue and bone cells in culture. Characterization and hormonal influences. Biochem J 1987; 248: 129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeier A , Niedzielska D , Secer R et al. Uptake of postprandial lipoproteins into bone in vivo: impact on osteoblast function. Bone 2008; 43: 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas J , Salas M , Vinuela E et al. Glucokinase of rabbit liver. J Biol Chem 1965; 240: 1014–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L , Reivich M , Kennedy C et al. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem 1977; 28: 897–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick AN , Drury DR , Nakada HI et al. Localization of the primary metabolic block produced by 2-deoxyglucose. J Biol Chem 1957; 224: 963–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps ME , Huang SC , Hoffman EJ et al. Tomographic measurement of local cerebral glucose metabolic rate in humans with (F-18)2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: validation of method. Ann Neurol 1979; 6: 371–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning JC , Michael MD , Winnay JN et al. A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell 1998; 2: 559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M , Xuan S , Bouxsein ML et al. Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 44005–44012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender D , Munk OL , Feng HQ et al. Metabolites of (18)F-FDG and 3-O-(11)C-methylglucose in pig liver. J Nucl Med 2001; 42: 1673–1678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher BM , Fowler JS , Gutterson NI et al. Metabolic trapping as a principle of oradiopharmaceutical design: some factors resposible for the biodistribution of [18F] 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose. J Nucl Med 1978; 19: 1154–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fueger BJ , Czernin J , Hildebrandt I et al. Impact of animal handling on the results of 18F-FDG PET studies in mice. J Nucl Med 2006; 47: 999–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J , Ferron M , Clarke CJ et al. Bone-specific insulin resistance disrupts whole-body glucose homeostasis via decreased osteocalcin activation. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebaud D , Jacot E , DeFronzo RA et al. The effect of graded doses of insulin on total glucose uptake, glucose oxidation, and glucose storage in man. Diabetes 1982; 31: 957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK , Michael MD , Previs SF et al. Redistribution of substrates to adipose tissue promotes obesity in mice with selective insulin resistance in muscle. J Clin Invest 2000; 105: 1791–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter EA , Hargreaves M . Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol Rev 2013; 93: 993–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry TM , Bitensky L , Chayen J et al. Early strain-related changes in enzyme activity in osteocytes following bone loading in vivo. J Bone Miner Res 1989; 4: 783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer WG , Donahue LR , Rosen CJ et al. Genetic variability in adult bone density among inbred strains of mice. Bone 1996; 18: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt V , Canalis E , Stadmeyer L et al. Age-related changes in trabecular architecture differ in female and male C57BL/6J mice. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22: 1197–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]