Abstract

Background:

Vitamin D deficiency (<32 ng/mL) is a reversible cause of statin-intolerance, usually requiring vitamin D3 (50,000-100,000 IU/week) to normalize serum D, allowing reinstitution of statins. Longitudinal safety assessment of serum vitamin D, calcium, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is important.

Aims:

Prospectively assess the safety-efficacy of vitamin D3 therapy.

Materials and Methods:

In 282 statin-intolerant hypercholesterolemic patients for 6 months and in 112 of the 282 patients for 12 months, with low-entry serum vitamin D (<32 ng/mL), we assessed safety-efficacy of vitamin D3 therapy (50,000-100,000 IU/week).

Results:

On mean (66,600 IU) and median (50,000 IU) of vitamin D3/week in 282 patients at 6 months, serum vitamin D rose from pretreatment (21—median) to 46 ng/mL (P < 0.0001), and became high (>100 ng/mL) but not toxic (>150 ng/mL) in 4 patients (1.4%). Median serum calcium was unchanged from entry (9.60 mg/dL) to 9.60 at 6 months (P = .36), with no trend of change (P = .16). Median eGFR was unchanged from entry (84 mL/min/1.73) to 83 at 6 months (P = .57), with no trend of change (P = .59). On vitamin D3 71,700 (mean) and 50,000 IU/week (median) at 12 months in 112 patients, serum vitamin D rose from pretreatment (21—median) to 51 ng/mL (P < 0.0001), and became high (>100 but <150 ng/mL) in 1 (0.9%) at 12 months. Median serum calcium was unchanged from entry (9.60 mg/dL) to 9.60 mg/dL and 9.60 mg/dL at 6 months and 12 months, respectively; P > 0.3. eGFR did not change from 79 mL/min/1.73 at entry to 74 mL/min/1.73 and 77 mL/min/1.73 at 6 months and 12 months, P > 0.3. There was no trend in the change in serum calcium (P > 0.5 for 6 months and 12 months), and no change of eGFR for 6 months and 12 months, P > 0.15.

Conclusions:

Vitamin D3 therapy (50,000-100,000 IU/week) was safe and effective when given for 12 months to reverse statin intolerance in patients with vitamin D deficiency. Serum vitamin D rarely exceeded 100 ng/mL, never reached toxic levels, and there were no significant change in serum calcium or eGFR.

Keywords: Deficiency, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hypercalcemia, myalgia, myositis, hypervitaminosis D, serum calcium, supplementation, Vitamin D

Introduction

To understand the safety parameters of therapeutic vitamin D supplementation, it is important to know that 10,000-25,000 IU/day are made in the skin in response to adequate sunlight exposure.[1,2,3,4,5]

From 1934 to 1946, supraphysiological doses of vitamin D (25(OH)D) were used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (200,000-600,000 IU/day),[6] 60,000-300,000 IU/day for asthma[7] and 100,000-150,000 IU/day for tuberculosis.[8] However, after months of supplementation at these doses, hypercalcemia often appeared,[6,7] with reports of resultant deaths.[9,10] Subsequently, much smaller doses of vitamin D were used to treat rickets, limited to 200 units per day.[11]

According to the Institute of Medicine, a serum 25(OH)D level of 25 ng/mL is adequate for most of the population[12] while levels >50 are high. However, much more widely used clinical normal ranges are 30-100 ng/mL[13] or 32-100 ng/mL.[4] Serum 25(OH)D of 100 ng/mL is considered by several groups to be the laboratory upper normal limit.[4,13] In treating chronic plaque psoriasis, serum vitamin D levels >50 and ranging up to 112 ng/mL were not a cause for concern.[14]

Many studies have been conducted to assess the adverse outcomes of vitamin D supplementation at various dose levels.[3,15,16,17,18,19] In normal healthy subjects, no adverse outcome was reported by Heaney et al.,[15] giving 836 IU/day, 5500 IU/day or 11,000 IU/day. Serum vitamin D levels rose from 28.1 to 64 ng/mL in 5 months in the 5,500 IU/day group, and rose to 88 ng/mL in the 11,000 IU/day group.[15] Ten thousand units/day has been proposed as a safe tolerable upper intake level, and it has been estimated that serum 25(OH)D levels >240 ng/mL would be required to result in clinically significant hypercalcemia.[16] In 2011, a community-based study with 3,667 subjects reported that dosing with 10,000 IU/day was safe, with no reported serum 25(OH)D level >200 ng/mL.[17] With 4,000 IU/day of D3 given for 1 year in two studies, no adverse effect due to vitamin D supplementation was reported,[18,19] and mean serum 25(OH)D levels after 12 months were 66ng/mL and 67 ng/mL.

In a 10-year population study, the incidence of serum 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL increased significantly without a corresponding increase in serum calcium values or with the risk of hypercalcemia.[20] As recently summarized by Hossein-Nezhad and Holick, “serum 25(OH)D levels are usually markedly elevated (>150 ng/ml) in individuals with vitamin D intoxication,”[21] and daily doses of vitamin D3 up to 10,000 IU were safe in healthy males.[15,16]

One potential adverse outcome of high dose oral vitamin D supplementation might be the development of nephrocalcinosis but kidney stone development has not been reported for patients taking oral vitamin D3 up to 11,000 IU per day.[2,15,16,17,18,19] Moreover, there are no links reported[22,23,24,25] between oral vitamin D intake and development of kidney stones.

Statin-induced myalgia is a major cause of statin intolerance[26,27,28,29,30] and is common, reported in 27% of the subjects treated with statins.[29] Statin therapy in community-dwelling older adults may exacerbate muscle performance decline and falls associated with aging without a concomitant decrease in muscle mass, a reversible effect after the cessation of statins.[31]

Most[24,26,27,28,32,33,34,35,36,37] but not all[38,39,40] recent studies have suggested that low serum vitamin D additively or synergistically interacts with statins to produce myalgia-myopathy.

Since myalgia, myositis, myopathy, and/or myonecrosis are the major causes of statin intolerance,[41] and the association of serum vitamin D deficiency, statin treatment, and myalgia, myositis, myopathy and/or myonecrosis has physiologic plausibility,[42,43,44,45,46,47] resolution of vitamin D deficiency interacting with statins to produce myalgia, myositis, myopathy, and/or myonecrosis would have significant clinical importance, allowing reinstitution of statins to optimize reduction of Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC) and prevent cardiovascular disease.[48]

In the current study, our specific aim was determine whether and to what degree vitamin D3 supplementation of 50,000-100,000 IU/week for 6-12 months in 282 vitamin D-deficient, statin-intolerant patients was safe with regard to the development of serum hypervitaminosis D, hypercalcemia, or changes in the calculated estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board-approved protocol

The study followed an institutional review board-approved protocol with signed informed consent.

Statin-intolerant patients with low serum vitamin D (<32 ng/mL)

In the temporal order of their referral from Midwestern physicians (Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, West Virginia), we prospectively studied hypercholesterolemic patients with statin intolerance (unable to tolerate ≥2 statins) who were found by us to have serum 25(OH)D <32 ng/mL, our laboratory lower normal limit. After experiencing myalgia, myositis, myopathy, and/or myonecrosis, most referred patients refused to take another statin unless steps were taken to explicate and treat[26,27,28,48] the pathoetiology of their statin intolerance.

We excluded patients who had previously developed rhabdomyolysis during statin therapy and those who were taking corticosteroids at study entry or who had comorbidities that would result in muscle or bone pain (diabetic sensory neuropathy, fibromyalgia, polymyalgia rheumatica, arthritis, peripheral vascular disease, sensory neuropathy, and hypothyroidism). Age was not used as an inclusion or exclusion criterion. After the above inclusions and exclusions, we prospectively studied 282 patients treated with 50,000-100,000 IU vitamin D3/week for 6 months, and 112 of these 282 patients for 12 months.

Laboratory determinations

At the initial visit, after an overnight fast, blood was drawn and measured for serum total 25(OH)D by LabCorp using two-dimensional liquid chromatography (HPLC) with tandem mass spectrometry detection after protein precipitation.[49] The laboratory lower normal limit for total 25(OH)D was 32 ng/mL.[49] Additional measures included plasma cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL cholesterol (HDLC), and LDLC, serum calcium, and phosphorous, along with creatine phosphokinase (CK), glucose, insulin, and renal (electronic GFR), thyroid, and liver function tests. At each follow-up visit, fasting blood was obtained for serum total 25(OH)D levels, serum calcium and phosphorous, eGFR, lipid profile, CK, glucose, and liver function tests.

Vitamin D supplementation and prospective follow-up

After documentation of low serum 25(OH)D at study entry, the 282 statin-intolerant, vitamin D-deficient patients were started on vitamin D3 by prescription[50] with 161 (57%) given ≤50,000 IU/week (median: 50,000 units/week) and 113 (40%) >50,000 IU/week but ≤100,000 IU/week (median 100,000 units/week). Only 8 patients (2.8%) were given >100,000 IU/week, with the highest dose 150,000 IU/week in 3 patients.

Patients were prospectively reassessed at 6-month intervals for 1 year [Table 1 and Figures 1–2], with remeasurement of serum vitamin D, serum calcium, and eGFR. At each follow-up visit, a detailed history was obtained for statin and prescription drug use, and the amount of vitamin D supplementation.[48]

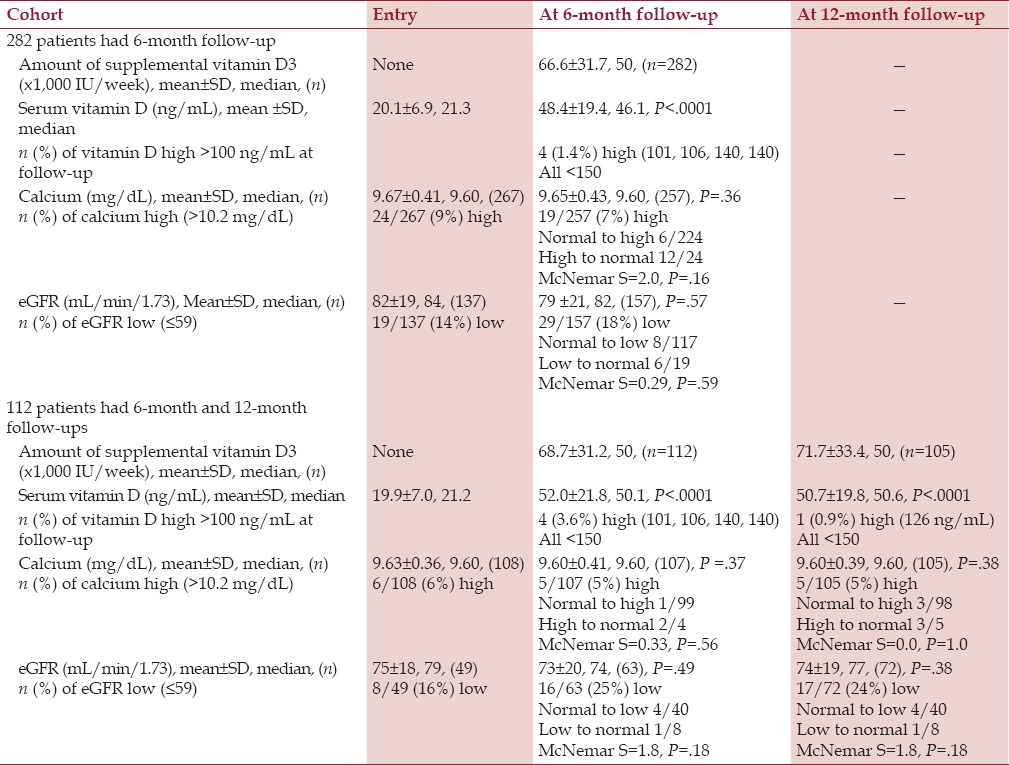

Table 1.

Serum vitamin D, calcium, and eGFR at pretreatment entry and up to 6-month and 12-month therapies with 50,000-100,000 IU/week of vitamin D3

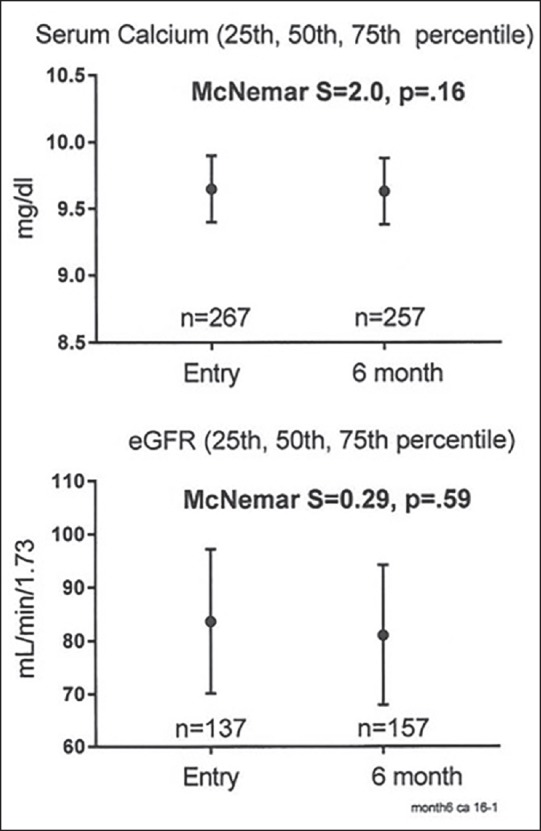

Figure 1.

Serum calcium and eGFR at pretreatment entry and at the 6-month follow-up on vitamin D3 supplementation in 282 patients, median, 25th-75th percentiles are exhibited

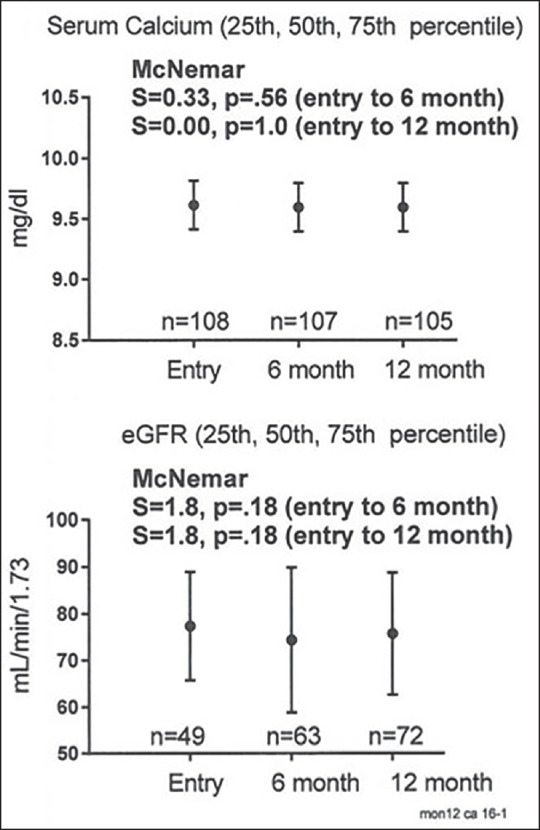

Figure 2.

Serum calcium and eGFR at pretreatment entry and at the 6-month, 12-month follow-ups on vitamin D3 supplementation in 112 patients, median, and 25th-75th percentiles are exhibited

Statistical methods

Based on our recent study of 146 vitamin D-deficient, statin-intolerant patients with pretreatment serum vitamin D 21 ± 7 ng/mL and levels 57 ± 19 ng/mL on supplementation,[48] power and sample size were calculated. We would have needed 24 patients before and on vitamin D supplementation to be able to observe the vitamin D treatment effect, with serum vitamin D increasing at least 20 ng/mL at a significance level of P = 0.05, with power of 80%.

Differences between pretreatment serum vitamin D, calcium, and eGFR and levels at 6 months and 12 months on vitamin D supplementation were assessed by paired Wilcoxon tests of difference. McNemar's tests were used to check trends over time in serum calcium and eGFR (normal→abnormal or abnormal→normal).

Results

Follow-up for 6 months

As summarized in Table 1, at study entry there were 282 patients (155 men, 127 women) who had measurements of serum 25(OH)D at pretreatment entry and at 6-month follow-up. By selection, pretreatment serum vitamin D was low (<32 ng/mL) in all patients, with median levels of 21.3 ng/mL [Table 1]. On 6-month follow-up on vitamin D supplementation (median 50,000 IU D3/week), median serum vitamin D rose to 46.1 ng/mL (P <.0001). Of the 282 patients, serum vitamin D levels rose into the normal range (>32 ng/mL) in 222 (79%), with 56 (20%) still low (<32 ng/mL) (median: 25 ng/mL). Serum vitamin D levels rarely rose above the laboratory upper normal limit (100 ng/mL) (n = 4, 1.4% of 282 patients, 101 ng/mL, 106 ng/mL, 140 ng/mL, 140 ng/mL) at 6-month follow-up [Table 1].

On vitamin D supplementation, no patient had serum vitamin D levels in the hypervitaminosis range (>150 ng/mL) [Table 1]. On vitamin D supplementation, serum calcium was unchanged (P = .36), as was eGFR (P = .57). There was no significant trend of change in serum calcium (McNemar P = .16) or in eGFR (P = .59) from entry to 6-month follow-up [Table 1 and Figure 1].

Of the 282 patients with pretreatment serum vitamin D <32 ng/mL, 183 were unable to tolerate any statin pre-vitamin D treatment because of myalgia-myositis. At 6-month follow-up on vitamin D supplementation, 136 of these 183 patients (74%) were able to tolerate statin therapy without myalgia-myositis. Of the 99 patients taking statins at the study entry, at 6-month follow-up on vitamin D supplementation 84 (85%) continued statins without symptoms.

Sequential follow-up for 12 months

Of the 282 patients, 112 (65 men, 47 women) had both 6-month and 12-month follow-ups on vitamin D3 supplementation (median 50,000 IU/week). Median serum vitamin D rose to the normal range and remained in it [Table 1]. On vitamin D supplementation, 87 of the 112 patients (78%) had serum vitamin D in the normal range (32-100 ng/mL) and 21 (19%) had serum vitamin D still low at 6 months (median 26 ng/mL). At 12 months, 87/112 (78%) patients had vitamin D in the normal range, and 24 (21%) had serum vitamin D below 32 (median 26 ng/mL). Serum vitamin D levels rarely rose above the laboratory upper normal limit (100 ng/mL) [n = 4 ng/mL, 101 ng/mL, 106 ng/mL, 140 ng/mL, 140 ng/mL, (3.6%) at 6 months, n = 1, 126 ng/mL (0.9%) at 12 months], and no patient had serum vitamin D levels in the hypervitaminosis range (>150 ng/mL) [Table 1].

At follow-up, on vitamin D3 supplementation, serum calcium was unchanged (P = .37 for month 6, P = .38 for month 12) as was GFR (P = .49 for month 6, P = .38 for month 12). There was no significant trend of change in serum calcium (P > .5) or in eGFR (P > .1) by McNemar's test [Table 1 and Figure 2].

Of the 112 patients with pretreatment serum vitamin D <32 ng/mL, and 12-month follow-up, 82 were unable to tolerate any statin pre-vitamin D treatment because of myalgia-myositis. At 12-month follow-up on vitamin D supplementation, 74 (90%) of these 82 patients were able to tolerate statin therapy without myalgia-myositis. Of the 30 patients taking statins at study entry, at 12-month follow-up on vitamin D supplementation, 29 (97%) continued statins without symptoms.

Discussion

Low serum vitamin D is associated with statin intolerance in most studies,[26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36] and vitamin D3 supplementation appears to reverse statin intolerance in most studies[33,34,35,37] including our four previous reports.[26,27,28,48]

In our most recent study of 146 vitamin D-deficient, statin-intolerant patients,[48] the amount of vitamin D3 supplementation used was 50,000-100,000 units/week, and there was no adverse effect at this level of supplementation. In the current study, in a larger cohort of statin-intolerant patients with low pretreatment serum vitamin D (<32 ng/mL), with vitamin D3 supplementation of 50,000-100,000 units/week, there was no significant change in calcium levels and no significant change in eGFR. Moreover, none of the patients developed serum vitamin D levels >150 ng/mL, conventionally identified as hypervitaminosis D,[21] and very few (<4%) had serum vitamin D levels above the laboratory upper normal limit of 100 ng/mL. In the current study, vitamin D3 supplementation (50,000-100,000 units/week) for amelioration of vitamin D-dependent statin intolerance[26,27,28,48] was safe, as determined by the lack of change in serum calcium, eGFR, or development of hypervitaminosis D.

In the current study, at 6-month and 12-month follow-ups on vitamin D supplementation, 74% and 90%, respectively, of statin-intolerant patients, none of whom would take any statin at the pretreatment baseline, were able to successfully take statins.

Our finding of the safety of vitamin D3 supplementation of 50,000-100,000 units per week is paralleled by previous studies providing 11,000 units per day.[15,16] As recently summarized by Hossein-Nezhad and Holick, “…daily doses of vitamin D3 up to 10,000 IU were safe in healthy males.”[21]

Our paper is limited as it is not double-blind and placebo-controlled but this design is difficult to carry out in statin-intolerant patients who refuse, as did the patients in the current study, to try any new statin therapy without an antecedent attempt to reverse low serum vitamin D at study entry.

Overall, in our initial four reports[26,27,28,48] we have provided supplemental vitamin D3 to 402 statin-intolerant patients with low serum vitamin D at entry, of whom 352 (88%) were subsequently able to tolerate a rechallenge of statins with excellent tolerability and LDLC lowering to targeted levels.[51] The documentation of safety of 50,000-100,000 IU/week of vitamin D3 supplementation for up to 1-year follow-up as documented in the current study is important, given the utility of vitamin D supplementation as an approach to reverse statin intolerance.[48]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tavera-Mendoza LE, White JH. Cell defenses and the sunshine vitamin. Sci Am. 2007;297:62–5. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1107-62. 68-70, 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamp TC, Haddad JG, Twigg CA. Comparison of oral 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, vitamin D, and ultraviolet light as determinants of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Lancet. 1977;1:1341–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:842–56. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: Implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005;135:317–22. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreyer I, Reed CI. The treeatment of arthritis with massive doses of vitamin D. Archives of Physical Therapy. 1935;16:537–43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rappaport BZ, Reed CI, Hathaway ML, Struck HC. The treatment of hay fever and asthma with Viosterol of high potency. J Allergy. 1934;5:541–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowling GB, Thomas EW, Wallace HJ. Lupus vulgaris treated with calciferol. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1946;39:225–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leake CD. Vitamin D toxicity. Cal West Med. 1936;44:149–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bevans M, Taylor HK. Lesions following the use of ertron in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol. 1947;23:367–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gartner LM, Greer FR. Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition. American Academy of Pediatrics. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency: New guidelines for vitamin D intake. Pediatrics. 2003;111:908–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan C, Moran B, McKenna MJ, Murray BF, Brady J, Collins P, et al. The effect of narrowband UV-B treatment for psoriasis on vitamin D status during wintertime in Ireland. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:836–42. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heaney RP, Davies KM, Chen TC, Holick MF, Barger-Lux MJ. Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:204–10. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:6–18. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garland CF, French CB, Baggerly LL, Heaney RP. Vitamin D supplement doses and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the range associated with cancer prevention. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:607–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrett-Mayer E, Wagner CL, Hollis BW, Kindy MS, Gattoni-Celli S. Vitamin D3 supplementation (4000 IU/d for 1 y) eliminates differences in circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D between African American and white men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:332–6. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall DT, Savage SJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Keane TE, Hollis BW, Horst RL, et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation at 4000 international units per day for one year results in a decrease of positive cores at repeat biopsy in subjects with low-risk prostate cancer under active surveillance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2315–24. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudenkov DV, Yawn BP, Oberhelman SS, Fischer PR, Singh RJ, Cha SS, et al. Changing incidence of serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D values above 50 ng/mL: A 10-year population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:577–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossein-Nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin D for health: A global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:720–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen S, Baggerly L, French C, Heaney RP, Gorham ED, Garland CF. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in the range of 20 to 100 ng/mL and incidence of kidney stones. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1783–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pipili C, Oreopoulos DG. Vitamin D status in patients with recurrent kidney stones. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;122:134–8. doi: 10.1159/000351377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang J, McFann KK, Chonchol MB. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and nephrolithiasis: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988-94. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:4385–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penniston KL, Jones AN, Nakada SY, Hansen KE. Vitamin D repletion does not alter urinary calcium excretion in healthy postmenopausal women. BJU Int. 2009;104:1512–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glueck CJ, Abuchaibe C, Wang P. Symptomatic myositis-myalgia in hypercholesterolemic statin-treated patients with concurrent vitamin D deficiency leading to statin intolerance may reflect a reversible interaction between vitamin D deficiency and statins on skeletal muscle. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77:658–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed W, Khan N, Glueck CJ, Pandey S, Wang P, Goldenberg N, et al. Low serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels (<32 ng/mL) are associated with reversible myositis-myalgia in statin-treated patients. Transl Res. 2009;153:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glueck CJ, Budhani SB, Masineni SS, Abuchaibe C, Khan N, Wang P, et al. Vitamin D deficiency, myositis-myalgia, and reversible statin intolerance. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1683–90. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.598144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandenberg BF, Robinson J. Management of the patient with statin intolerance. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12:48–57. doi: 10.1007/s11883-009-0077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, Morrison F, Mar P, Shubina M, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott D, Blizzard L, Fell J, Jones G. Statin therapy, muscle function and falls risk in community-dwelling older adults. QJM. 2009;102:625–33. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palamaner Subash Shantha G, Ramos J, Thomas-Hemak L, Pancholy SB. Association of vitamin D and incident statin induced myalgia — A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee P, Greenfield JR, Campbell LV. Vitamin D insufficiency — A novel mechanism of statin-induced myalgia? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:154–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang S, Wu J. Resolution of statin-induced myalgias by correcting vitamin D deficiency. South Med J. 2011;104:380. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318213d123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell DS. Resolution of statin-induced myalgias by correcting vitamin D deficiency. South Med J. 2010;103:690–2. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mergenhagen K, Ott M, Heckman K, Rubin LM, Kellick K. Low vitamin D as a risk factor for the development of myalgia in patients taking high-dose simvastatin: A retrospective review. Clin Ther. 2014;36:770–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linde R, Peng L, Desai M, Feldman D. The role of vitamin D and SLCO1B1* gene polymorphism in statin-associated myalgias. Dermatoendocrinol. 2010;2:77–84. doi: 10.4161/derm.2.2.13509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurnik D, Hochman I, Vesterman-Landes J, Kenig T, Katzir I, Lomnicky Y, et al. Muscle pain and serum creatine kinase are not associated with low serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels in patients receiving statins. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riphagen IJ, van der Veer E, Muskiet FA, DeJongste MJ. Myopathy during statin therapy in the daily practice of an outpatient cardiology clinic: Prevalence, predictors and relation with vitamin D. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1247–52. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.702102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisen A, Lev E, Iakobishvilli Z, Porter A, Brosh D, Hasdai D, et al. Low plasma vitamin D levels and muscle-related adverse effects in statin users. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16:42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA. 2003;289:1681–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erkal MZ, Wilde J, Bilgin Y, Akinci A, Demir E, Bödeker RH, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, secondary hyperparathyroidism and generalized bone pain in Turkish immigrants in Germany: Identification of risk factors. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1133–40. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shinchuk LM, Holick MF. Vitamin d and rehabilitation: Improving functional outcomes. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:297–304. doi: 10.1177/0115426507022003297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bunout D, Barrera G, Leiva L, Gattas V, de la Maza MP, Avendaño M, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation and exercise training on physical performance in Chilean vitamin D deficient elderly subjects. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:746–52. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dietrich T, Orav EJ, Hu FB, Zhang Y, Karlson EW, et al. Higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with better lower-extremity function in both active and inactive persons aged > or = 60 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:752–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lips P. Vitamin D physiology. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glueck CJ, Conrad B. Severe vitamin d deficiency, myopathy, and rhabdomyolysis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:494–5. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.117325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khayznikov M, Hemachrandra K, Pandit R, Kumar A, Wang P, Glueck CJ. Statin intolerance because of myalgia, myositis, myopathy, or myonecrosis can in most cases be safely resolved by vitamin D supplementation. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:86–93. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.153919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsugawa N, Suhara Y, Kamao M, Okano T. Determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in human plasma using high-performance liquid chromatography — tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3001–7. doi: 10.1021/ac048249c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michalska-Kasiczak M, Sahebkar A, Mikhailidis DP, Rysz J, Muntner P, Toth PP, et al. Analysis of vitamin D levels in patients with and without statin-associated myalgia — A systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies with 2420 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2015;178:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]