Abstract

Prevention of blindness due to diabetic retinopathy (DR) requires effective screening strategies, for which eye care providers need to know the magnitude of the burden and the risk factors pertinent in their geographical location. It is estimated that around 72 million of the global adult population (around 8.2%) has diabetes and about one-fifth of all adults with diabetes lives in the South-East Asia. In India, around 65 million people have diabetes. As the global prevalence of diabetes increases, so will the number of people with diabetes-related complications, such as DR; nearly one-third of them are likely to develop this complication. This article reviews the present status of diabetes and DR in India, the current situation of DR services and the projections on the load of morbidity associated with retinopathy. The article compiles the Indian studies elucidating the risk factors for DR.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, incidence, prevalence, risk factors

Epidemic of Diabetes: Local Versus Global

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a global epidemic. It is estimated that 439 million people are likely to have DM by the year 2030 in the world and that this increase is disproportionately more in developing countries (69% in developing countries vs. 20% in developed countries with 2010 as baseline).[1] This will result in a heavy burden on the health care system because of several DM-related complications.

The Indian Council of Medical Research-India Diabetes study, the first national study to determine the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes (impaired fasting blood glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) in India in people >20 years found diabetes to be prevalent in all parts of the country with few differences. They estimated that in India 62.4 million people have diabetes, and 77.2 million people have prediabetes.[2]

Recently, the 10 years incidence study found the incidence of diabetes, prediabetes, and “any dysglycemia” in South Indian population was 22.2, 29.5, and 51.7 per 1000 person-years, respectively. Among those with normal glucose tolerance, the conversion rate to dysglycemia was 45.1%. Among those with prediabetes, 58.9% converted to diabetes.[3]

Asian Indian Phenotype of Diabetes and Influence on Retinopathy

The South Asian region is characterized by high prevalence rates of Type 2 diabetes, in spite of having a young population with relatively low levels of obesity. To explain this phenomenon, the existence of a “South Asian” or an “Asian Indian” phenotype has been postulated. This phenotype is characterized by higher waist circumference, higher levels of total and visceral fat, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and a greater predisposition to diabetes as compared with white Caucasians of comparable body mass index (BMI).[4] This phenotype makes Indians more prone to diabetes and early-onset coronary artery disease. This phenotype could be partly attributed to genetic factors. But, the main driver of the epidemic of diabetes is the rapid epidemiological transition associated with changes in dietary patterns and decreased physical activity as evident from the higher prevalence of diabetes in the urban population.

Chan et al. described examples of common clinical features in Asian populations with diabetes are the so-called “Asian phenotypes.” These include low BMI, increased body fat, especially visceral fat, high rate of central obesity and metabolic syndrome (MS), increased inflammatory markers, insufficient beta cell response to counter insulin resistance, low rate of autoimmune Type 1 diabetes, high rate of young-onset Type 2 diabetes, high rate of childhood obesity, high rate of gestational diabetes, social disparity and psychosocial stress, high rate of renal disease and high rate of cancer, especially those with viral causes, for example, liver cancer.[5]

It is difficult to assess how far does the presence of Asian phenotype influence diabetic retinopathy (DR). However, Raman et al. had reported the prevalence of MS in an urban cohort of Type 2 diabetes, using the International Diabetes Federation criteria, to be 73.3%. The prevalence was higher in women (83.3%) compared to men (65.3%).[6] There were no differences in the prevalence of retinopathy in subjects with DM, without and with MS. The clustering of MS components led to an increase in the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy but not retinopathy and neuropathy. Likewise, Raman et al. also reported that in the urban South Indian population, isolated abdominal obesity and higher waist-hip ratio in women is associated with DR, but not with the severity of DR.[7]

One of the most disturbing trends seen in India is the shift in age of onset of diabetes to a younger age in the recent years. This has a direct impact on nation's health and economy. It is also linked with a higher prevalence of retinopathy. Raman et al. reported that the prevalence of DR was almost twice more in those subjects who developed diabetes before the age of 40 years than those who developed it later.[8]

Diabetic Retinopathy: Global Scenario

Regional variations in prevalence, incidence, and progression

In a meta-analysis to compare the global prevalence of DR across ethnicities, the study found a lower prevalence of DR in Asians (19.9%) as compared to Caucasians (45.7%), African-Americans (49.6%), and Hispanics (34.6%); still the absolute number of people with DR was alarming. In India, in 1970–1975 DR was the 20th cause of blindness, and today, it is the 6th cause of blindness. Table 1 shows the regional differences in prevalence, incidence, and progression of DR in different global geographic regions.

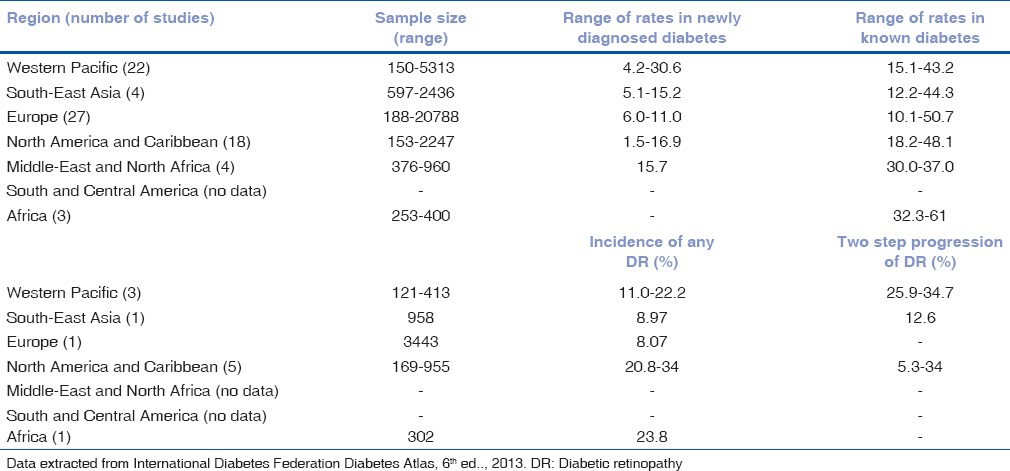

Table 1.

Region-wise global diabetic retinopathy prevalence, incidence, and progression

Regional differences in risk factors

Literature reports various risk factors associated with DR, of which, the common risk factors were age, increase in duration of diabetes, poor glycemic control in various regions. Aiello et al.[9] have reported that after 20 years of diabetes more than 60% of subjects with Type 2 diabetes will develop DR irrespective of their diabetic control which was confirmed by various other studies. Studies also suggest that duration of diabetes might reflect glycemic control and also exposure to other risk factors.[10] Studies from Western Pacific region report that low education level, increase in cerebrospinal fluid pressure, and short axial length are independent risk factors for DR, which was not reported in other studies.[11] MADIABETES cohort study reported a unique factor which was not observed in other studies that use of aspirin is an independent predictor of DR as they noticed that patients who developed DR have used aspirin in a higher percentage than those who did not develop DR.[12] Studies from South-East Asia and Africa report that middle and upper socioeconomic status groups and those subjects living in urban areas were at higher risk of developing DR.[13,14] Other factors associated with DR were men, hypertension, and the use of insulin.

Diabetic Retinopathy: Indian Scenario

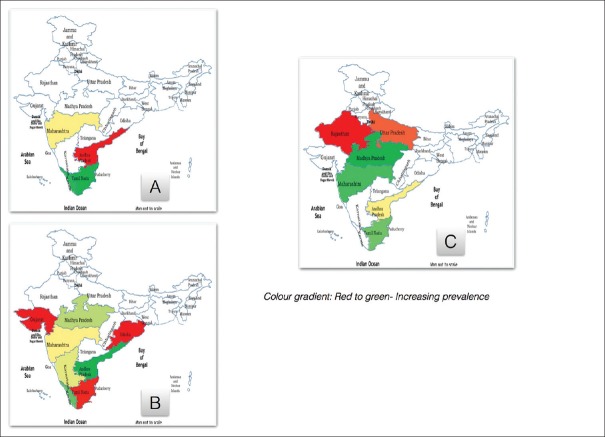

There are few population-based studies regarding DR in India. These are mainly from the Southern states; Fig. 1A shows the population-based studies in India which reported the prevalence of DR. There seems to be a rural-urban difference for the prevalence of DR. The prevalence of DR in urban areas is between 13–18% and in rural areas is 9–10%. Unlike diabetes, which shows regional variation, DR shows lesser regional differences.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in India: Population-based and self-reported studies. (A) Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy in population-based studies. (B) Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy in self-reported diabetics (World Diabetes Foundation funded projects). (C) Prevalence of Sight-threatening Diabetic Retinopathy in self reported diabetics (World Diabetes Foundation funded projects)

However, there are many reports from the clinic or self-reported Type 2 diabetes; which gives us information on the regional trends in DR. Fig. 1B and C show the prevalence of DR and sight-threatening DR (STDR) in self-reported group, across different service projects supported by the World Diabetes Foundation in India.

Sankara Nethralaya DR Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study found the 4-year incidence of any DR in Urban India to be 9%. The study found, in people who had DR at baseline, the incidence of diabetic macular edema (DME) and STDR increased to 11.5% and 22.7% respectively. This highlights the fact of detection of nonreferrable stages of DR and an appropriate follow-up to identify DME and STDR at an early stage. The 1-step and 2-step progression was seen in 30.2% and 12.6%, respectively.

Risk Factors in Indian Population

Epidemiological studies in many populations have identified clinical risk factors for DR. Population-based studies from India[15,16] have identified the following risk factors in Indian population. The most significant risk factor in both rural and urban India is the longer duration of diabetes (6.5 times more risk in people with > 15 years duration of diabetes).[15,17]

People who develop diabetes early in their life (before 40 years age) have double the risk of developing retinopathy and also sight-threatening retinopathy.[8] If a person is diagnosed to have diabetes, at the time of diagnosis of diabetes 1 in 10 would have nephropathy and neuropathy and 1 in 20 would have retinopathy.[18] Obesity increases the chances of developing DR. In Indian population, those with central obesity are associated with two times increased risk for DR.[7]

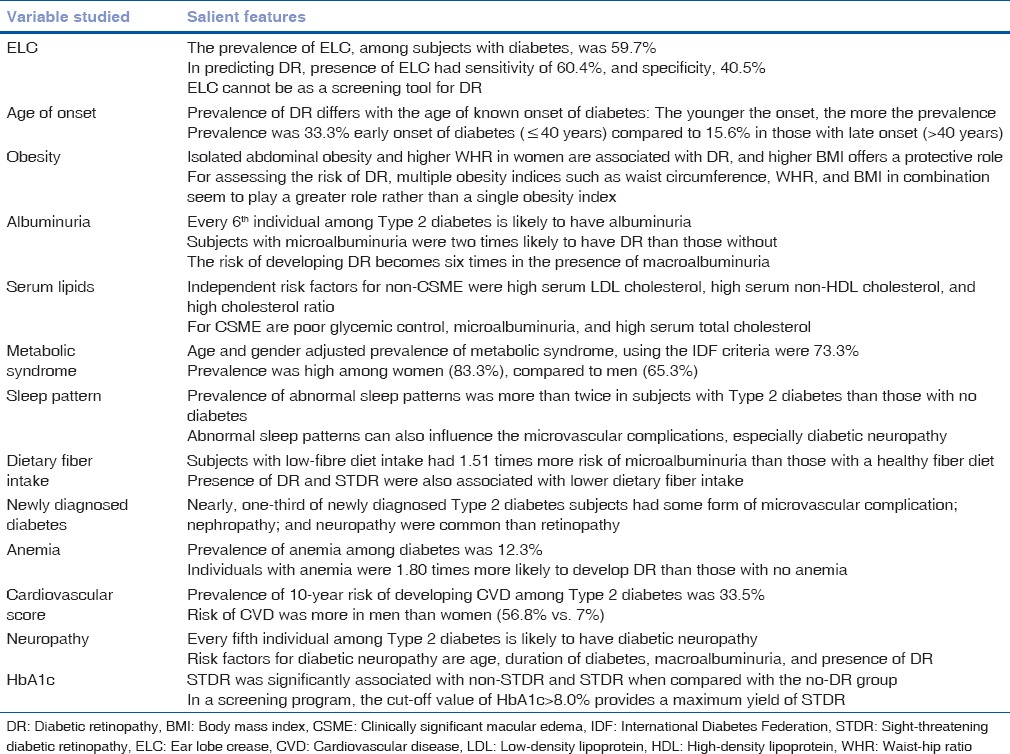

The occurrence of DR is more in diabetics who take low fiber diet in comparison with people who take high fiber diet (20% vs. 15%).[19] People with suboptimal glycemic control (HbA1c > 7) have more risk for having DR and those with poor control (HbA1c > 8) also had more risk of sight-threatening retinopathy.[20] Abnormal serum lipids (especially serum cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) have more role in DME (both in center involving and center not involving DME).[21] People with a combination of suboptimal control (blood sugar, blood pressure, and lipids) have greater risk of both retinopathy and sight-threatening retinopathy. Nearly, 1 in 3 diabetics with suboptimal control have retinopathy.[20] If a person has early nephropathy (presence of microalbuminuria) he has two times more risk of retinopathy. If he has advanced nephropathy (albuminuria) he has six times more risk of retinopathy.[22] Anemia is more prevalent in India, more so in women and has two times more risk of developing retinopathy.[23] Table 2 highlights the role of systemic risk factors in DR based on studies from the Indian subcontinent. Table 3 describes the Indian studies on other ocular parameters among people with diabetes.

Table 2.

Role of systemic risk factors in diabetic retinopathy based on studies from Indian subcontinent

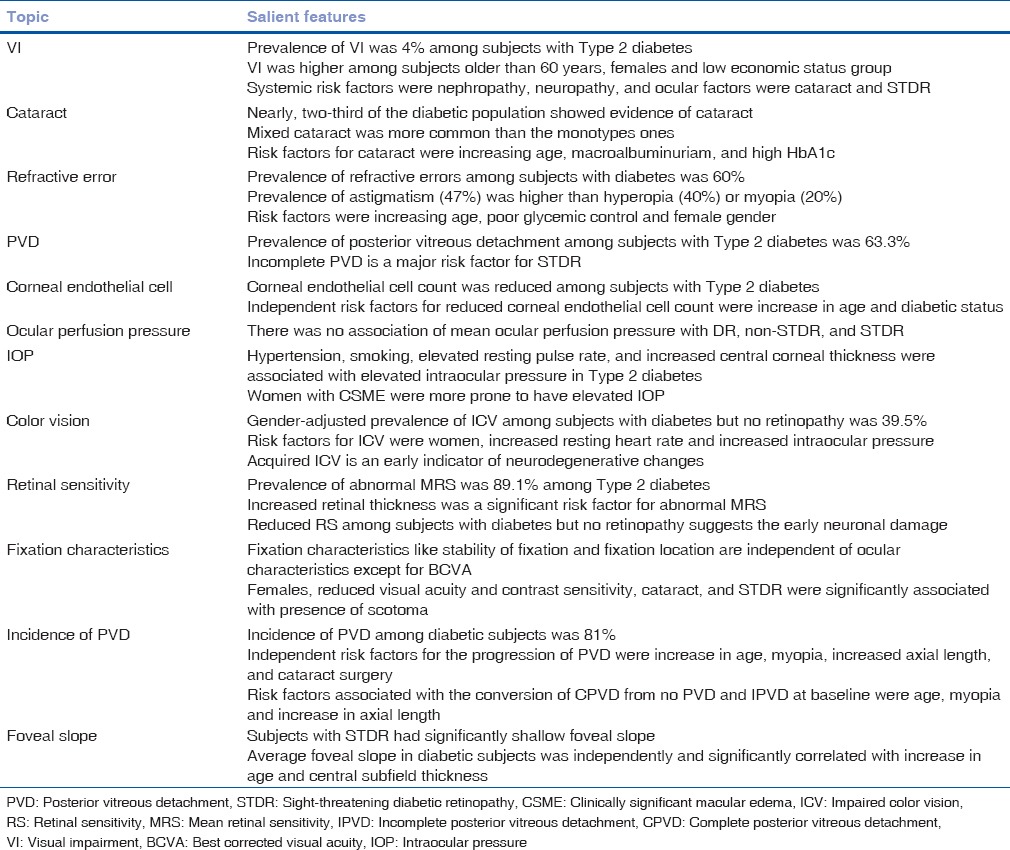

Table 3.

Other ocular parameters among people with diabetes from Indian studies

Genetic risk factors

In clinical practice, some patients seem to be having a protection against DR despite having multiple risk factors, while others exhibit severe vision-threatening complications even with fewer or no risk factors. Hence, many groups have started exploring the role of genetic factors in DR. There are few reports on genetic studies from India. But significant advancements are happening in basic research at the different major eye institutes in the country. One group from Southern India studied nine candidate genes (receptor for advanced glycation end product [RAGE], pigment epithelium derived factor [PEDF], AKR1B1, EPO, HTRA1, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM), HFE, CFH, and ARMS2) which were chosen based on their roles in biological pathways implicated in DR.[24] Among the 15 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) studied, in DR and diabetic patients without retinopathy (DNR), only 1 SNP rs2070600 (G > A) in exon 3 of RAGE, which leads to a change of amino acid glycine to serine at codon 82 displayed statistically significant (P = 0.016) association with DR in this study population.

Another group in India studied the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), PEDF, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), protein kinase C beta (PKC-β), aldose reductase 2 (ALR2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), RAGE, and ICAM-1 for their possible association with retinopathy in Indian population. Variants Z-2 of ALR2, (CA) 18 of IGF-1, and AA genotype of ICAM-1 have been identified as high-risk alleles,[25,26,27] whereas (GT)9 of tumor necrosis factor-β and (CCTTT)15 of iNOS genes were reported as low-risk alleles for retinopathy; however, variants Gly82Serand T130T in RAGE and PEDF genes, respectively, showed a protective association.[28,29] In addition, they also found the variants in the promoter and 3’ untranslated region in PKC-β and VEGF and the 27 bp intron four variable number tandem repeat in eNOS gene showing a lack of association with Type 2 DR in the South Indian population.[30,31] Recently, in a genome-wide association study, a subset of replication cohort from South India showed rs9896052 to be associated with STDR in Type 2 diabetes (P = 0.016).[32]

Diabetic Retinopathy: Projections for India

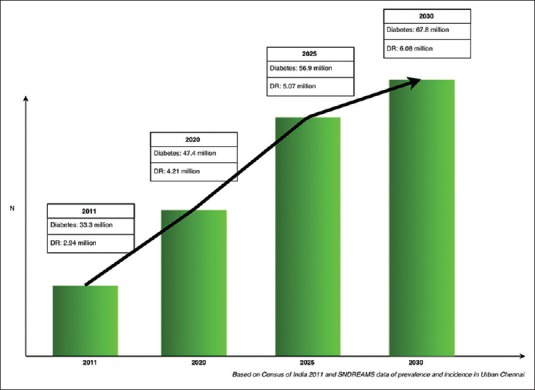

The number of people with diabetes (>40 years) is expected to increase to 79.4 million and patients with DR would increase to 22.4 million in another two decades.[1] This would imply approximately 2 million diabetics who would have STDR. Fig. 2 depicts the projections for a number of new cases of DR in India, based on a census of India 2011 and incidence and progression of DR based on SN-DREAMS urban data. India ranks third in the world in the number of Internet users by volume. In addition, 70% has access to mobile phones, and 39% of them live in rural areas. Teledensity has increased from merely 12.1% to 73.3%, a growth of 600%, during the past 5 years.[33] This makes screening of DR using imaging and teleophthalmology a distinct possibility that can revolutionize the health care system.

Figure 2.

Projections of new cases of diabetic retinopathy in urban India

Awareness Regarding Diabetic Retinopathy

The awareness about DR is low, both among the diabetics and the diabetic care providers. In a population-based study to determine knowledge, awareness, and practices relating to DR among paramedics in a South Indian population, it was found that over 50% of the respondents were not aware of risk factors for DR. Only one-fifth of paramedics and one-tenth of the people from the community were aware that uncontrolled diabetes was a risk factor for retinopathy. Although 80% of respondents from the community felt that yearly eye examinations were essential, only 43.5% had ever visited an ophthalmologist.[34]

In another study done at Chennai, it was found that the uptake of eye care was poor both in urban and in rural areas. Around 63% (n = 2168) of individuals in the rural areas and 75% (n = 2399) in the urban areas had never undergone an eye examination for DR. 45% (n = 139) of rural and 50% (n = 74) of urban diabetics who had sight-threatening retinopathy, had never undergone a fundus evaluation before.[35]

This lack of awareness in India warrants initiation of a mass awareness program on diabetes and its microvascular complications such as DR. Over period of time, increased awareness would result in improved utilization of health services.

Diabetic Retinopathy Screening in India

There is no national screening program for DR in India. Currently, screening in the country is undertaken on an ad hoc or project basis, and no optimal strategy has been developed at the national level. Different models have been developed for DR case finding in India, and they are implemented to varying degrees of success across the country.

Screening camps

These camps screen people with diabetes for STDR and those with STDR are referred for treatment.[36,37] Outreach screenings camps are conducted in the community with the help of physicians with the help of local community participation. Here, known diabetics are screened for DR by an ophthalmologist - based strategy. These camps increase awareness in the community regarding retinopathy.

Telemedicine

This method tackles the problem of access. Nonmydriatic digital retinal images are taken for people with diabetes. These images are then transmitted to an expert who reads them remotely.[38] Mobile vans with communication capabilities have been deployed in the community with fundus cameras in various states of India. The pooled diabetic patient's fundus pictures are captured and sent to a centralized reading center by a telecommunication network. The images are graded and a report is generated and sent back to the mobile van. The patient receives this report along with counseling for further follow-up and treatment. Using the World Health Organization threshold of cost-effectiveness, telescreening in India is found to be cost-effective ($1320 per quality-adjusted life year) compared to no screening by a health provider perspective.[39]

Opportunistic screening

In this approach, diabetics are screened when they visit their physician or diabetologist. A trained technician takes the fundus photos of these diabetic patients using nonmydriatic fundus cameras and sends them to a centralized reading center or an ophthalmologist. The images are read and a report is generated and sent back to the diabetic center on the same day. The patient is advised accordingly based on the report received.

Physicians also do a screening using direct ophthalmoscopy (DO); however, according to a study in South India, only 1.3% of general practitioners actually use DOs. Among them, only 50% practice DO after dilatation. The barriers for doing DR screening among general practitioners are a lack of time, lack of ophthalmoscopes, and lack of training.[40]

Ophthalmologists in India

The burden of DR in India can be tackled only by a pool of well-qualified, efficient, and geographically and culturally accessible ophthalmologists and supporting eye care infrastructure. However, there are wide variations in the accessibility to ophthalmic care in India. Against a national ophthalmologist: Population ratio of 1:107,000, there are certain regions in India which have a ratio of 1:9000 while in other regions there is only one ophthalmologist for 608,000 population.[41]

There is limited information regarding ophthalmologists in India who are specialized in retinal diseases. With increasing short-term fellowship programs in medical retina, there is also now an overlap of anterior segment practicing ophthalmologists who also treat DR. As of 2012, there are 655 ophthalmologists who are registered in the Vitreoretinal Society of India. In 2015, based on the Novartis India user data, 1058 ophthalmologists inject intravitreal ranibizumab across India. This number is far less to tackle the projected load of DR in India.

In India, services for people with diabetes and for blindness control are provided by the public health system as well as private practitioners and the not-for-profit sector. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has a program for control of noncommunicable diseases (the National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke) and for blindness (the National Blindness Control Program). The Government of India, through its National Program for Control of Blindness, has included support for laser treatment for DR in its 11th 5-year-plan. A range of different approaches is being used by the government and not-for-profit sector in India to detect and treat DR.

The burden of DR in India can be tackled by increasing awareness among people living with diabetes providing an educational package for physicians, and other staff who care for diabetics and by extending programs for the detection and treatment of DR, which are integrated into the Government of India health system.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Sudha V, Unnikrishnan R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) in urban and rural India: Phase I results of the Indian Council of Medical Research-INdia DIABetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3022–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anjana RM, Shanthi Rani CS, Deepa M, Pradeepa R, Sudha V, Divya Nair H, et al. Incidence of diabetes and prediabetes and predictors of progression among Asian Indians: 10-year follow-up of the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1441–8. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeigue PM, Shah B, Marmot MG. Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Lancet. 1991;337:382–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91164-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan JC, Yeung R, Luk A. The Asian diabetes phenotypes: Challenges and opportunities. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105:135–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raman R, Gupta A, Pal SS, Ganesan S, Venkatesh K, Kulothungan V, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its influence on microvascular complications in the Indian population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study (SN-DREAMS, report 14) Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:67. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-2-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raman R, Rani PK, Gnanamoorthy P, Sudhir RR, Kumaramanikavel G, Sharma T. Association of obesity with diabetic retinopathy: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study (SN-DREAMS Report no 8) Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:209–15. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raman R, Vaitheeswaran K, Vinita K, Sharma T. Is prevalence of retinopathy related to the age of onset of diabetes?. Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Report No 5. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;45:36–41. doi: 10.1159/000314720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiello LP, Gardner TW, King GL, Blankenship G, Cavallerano JD, Ferris FL, 3rd, et al. Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:143–56. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giloyan A, Harutyunyan T, Petrosyan V. The prevalence of and major risk factors associated with diabetic retinopathy in Gegharkunik province of Armenia: Cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:46. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Xu L, Wang YX, You QS, Jonas JB, Wei WB. Ten-year cumulative incidence of diabetic retinopathy. The Beijing eye study 2001/2011. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salinero-Fort MÁ, San Andrés-Rebollo FJ, de Burgos-Lunar C, Arrieta-Blanco FJ, Gómez-Campelo P. MADIABETES Group. Four-year incidence of diabetic retinopathy in a Spanish cohort: The MADIABETES study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnaiah S, Das T, Nirmalan PK, Shamanna BR, Nutheti R, Rao GN, et al. Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: Findings from the Andhra Pradesh eye disease study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2007;1:475–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyari F, Tafida A, Sivasubramaniam S, Murthy GV, Peto T, Gilbert CE. Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Study Group. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: Results from the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raman R, Rani PK, Reddi Rachepalle S, Gnanamoorthy P, Uthra S, Kumaramanickavel G, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in India: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study Report 2. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradeepa R, Anjana RM, Unnikrishnan R, Ganesan A, Mohan V, Rema M. Risk factors for microvascular complications of diabetes among South Indian subjects with type 2 diabetes – The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) eye study-5. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:755–61. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raman R, Ganesan S, Pal SS, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in rural India. Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study III (SN-DREAMS III), report no 2. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014;2:e000005. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2013-000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raman R, Gupta A, Krishna S, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic microvascular complications in newly diagnosed type II diabetes mellitus. Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study (SN-DREAMS, report 27) J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganesan S, Raman R, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Influence of dietary-fibre intake on diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: Sankara Nethralaya-Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study (report 26) Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:288–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raman R, Gupta A, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in subjects with suboptimal glycemic, blood pressure and lipid control. Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study (SN-DREAMS, Report 33) Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:513–23. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.669005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raman R, Rani PK, Kulothungan V, Rachepalle SR, Kumaramanickavel G, Sharma T. Influence of serum lipids on clinically significant versus nonclinically significant macular edema: SN-DREAMS report number 13. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:766–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rani PK, Raman R, Gupta A, Pal SS, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Albuminuria and diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study (SN-DREAMS, report 12) Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2011;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranil PK, Raman R, Rachepalli SR, Pal SS, Kulothungan V, Lakshmipathy P, et al. Anemia and diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balasubbu S, Sundaresan P, Rajendran A, Ramasamy K, Govindarajan G, Perumalsamy N, et al. Association analysis of nine candidate gene polymorphisms in Indian patients with type 2 diabetic retinopathy. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumaramanickavel G, Sripriya S, Ramprasad VL, Upadyay NK, Paul PG, Sharma T. Z-2 aldose reductase allele and diabetic retinopathy in India. Ophthalmic Genet. 2003;24:41–8. doi: 10.1076/opge.24.1.41.13889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uthra S, Raman R, Mukesh BN, Rajkumar SA, Kumari RP, Agarwal S, et al. Diabetic retinopathy and IGF-1 gene polymorphic cytosine-adenine repeats in a Southern Indian cohort. Ophthalmic Res. 2007;39:294–9. doi: 10.1159/000108124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinita K, Sripriya S, Prathiba K, Vaitheeswaran K, Sathyabaarathi R, Rajesh M, et al. ICAM-1 K469E polymorphism is a genetic determinant for the clinical risk factors of T2D subjects with retinopathy in Indians: A population-based case-control study. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001036. pii: E001036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumaramanickavel G, Ramprasad VL, Sripriya S, Upadyay NK, Paul PG, Sharma T. Association of Gly82Ser polymorphism in the RAGE gene with diabetic retinopathy in type II diabetic Asian Indian patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2002;16:391–4. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uthra S, Raman R, Mukesh BN, Rajkumar SA, Kumari PR, Lakshmipathy P, et al. Protein kinase C beta (PRKCB1) and pigment epithelium derived factor (PEDF) gene polymorphisms and diabetic retinopathy in a South Indian cohort. Ophthalmic Genet. 2010;31:18–23. doi: 10.3109/13816810903426231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uthra S, Raman R, Mukesh BN, Rajkumar SA, Padmaja KR, Paul PG, et al. Association of VEGF gene polymorphisms with diabetic retinopathy in a south Indian cohort. Ophthalmic Genet. 2008;29:11–5. doi: 10.1080/13816810701663527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uthra S, Raman R, Mukesh BN, Padmaja Kumari R, Paul PG, Lakshmipathy P, et al. Intron 4 VNTR of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene and diabetic retinopathy in type 2 patients in Southern India. Ophthalmic Genet. 2007;28:77–81. doi: 10.1080/13816810701209669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burdon KP, Fogarty RD, Shen W, Abhary S, Kaidonis G, Appukuttan B, et al. Genome-wide association study for sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy reveals association with genetic variation near the GRB2 gene. Diabetologia. 2015;58:2288–97. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3697-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telecom Regulatory Authority of India. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 24]. Available from: http://www.trai.gov.in/WriteReadData/WhatsNew/Documents/IndicatorReports-01082013 .

- 34.Namperumalsamy P, Kim R, Kaliaperumal K, Sekar A, Karthika A, Nirmalan PK. A pilot study on awareness of diabetic retinopathy among non-medical persons in South India. The challenge for eye care programmes in the region. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2004;52:247–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rani PK, Raman R, Paul PG, Agarwal S, Kumaramanickavel G, Sharma T. Use of eye care services by people with diabetes – South Indian experience. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;82:410–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Namperumalsamy P, Nirmalan PK, Ramasamy K. Developing a screening program to detect sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy in South India. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1831–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rani PK, Raman R, Agarwal S, Paul PG, Uthra S, Margabandhu G, et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening model for rural population: Awareness and screening methodology. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5:350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liesenfeld B, Kohner E, Piehlmeier W, Kluthe S, Aldington S, Porta M, et al. A telemedical approach to the screening of diabetic retinopathy: Digital fundus photography. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:345–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rachapelle S, Legood R, Alavi Y, Lindfield R, Sharma T, Kuper H, et al. The cost-utility of telemedicine to screen for diabetic retinopathy in India. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:566–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raman R, Paul PG, Padmajakumari R, Sharma T. Knowledge and attitude of general practitioners towards diabetic retinopathy practice in South India. Community Eye Health. 2006;19:13–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar R. Ophthalmic manpower in India – Need for a serious review. Int Ophthalmol. 1993;17:269–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01007795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]