Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the safety of injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate during core decompression and to study its clinical (visual analogue scale; Harris-Hip-score) and radiological outcomes (magnetic resonance imaging). In this prospective and randomized clinical trial we evaluated 24 consecutive patients with non-traumatic femoral head necrosis (FHN) during a period of two years after intervention. In vitro analysis of mesenchymal stem cells was performed by evaluating the fibroblast colony forming units (CFU-Fs). Postoperatively, significant decrease in pain associated with a functional benefit lasting was observed. However, there was no difference in the clinical outcome between the two study groups. Over the period of two years there was no significant difference between the head survival rate between both groups. In contrast to that, we could not perceive any significant change in the volume of FHN in both treatment groups related to the longitudinal course after treating. The number of CFU showed a significant increase after centrifugation. This trial could not detect a benefit from the additional injection of bone marrow concentrate with regard to bone regeneration and clinical outcome in the short term.

Key words: Femoral head necrosis, core decompression, mesenchymal stem cells, autologous bone marrow concentrate

Introduction

Aseptic non-traumatic avascular osteonecrosis of the femoral head is a multi-factorial disease, the etiology of which is not entirely clear. Femoral head necrosis (FHN) most commonly affects young patients, often leading to femoral head collapse and resulting secondary osteoarthritis.1 Around 10% of all THA are performed due to FHN.2 In the early stages of the disease [Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) stage I - II] the treatment aims to preserve the joint and to prevent the collapse of the femoral head. One of the most widely used treatment options is the core decompression by retrograde drilling into the necrotic zone. Systematic reviews verified the significantly better head survival rates compared to non-operative treatment options.2 Based on the data by Mont et al., core decompression leads to clinical success in 53-71% of treated patients leaving room for further therapy improvement. Mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts that could potentially induce bone formation have been shown to be decreased in both number and activity in afflicted bone. Therefore the local application of autologous mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) into the necrotic region could stimulate the regeneration of the affected bone. MSCs can be isolated from the mononuclear cell fraction of bone marrow and expanded in-vitro to high-cell numbers using laboratory equipment and then injected into the necrotic zone.3 Bone marrow expansion is subject to restricted regulatory laws in many countries.Introduction of a single-use closed system would allow the surgical team to carry out the concentration procedure in the operating room.4 Hernigou et al. introduced the technique of intra-osseous injection of autologous concentrated bone marrow for the treatment of femoral osteonecrosis and pseudarthrosis.5 They reported on the results of core decompression with additional bone marrow grafting in 145 hips with early stage osteonecrosis (ARCO I - II). At 5 years after surgery, the head survival rate in their study was 93%, which would appear to be a considerable improvement over previous studies. Although this prospective study included an impressive number of patients, a control group and a randomized study protocol were missing. The aim of this study was i) to investigate the safety of additional injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) during core decompression and ii) to study the clinical (visual analogue scale, VAS; Harris-Hip-Score, HHS) and radiological outcome (magnetic resonance tomography, MRI) in comparison to core decompression only. In addition, in vitro analysis of MSCs was performed by evaluating the fibroblast colony forming units (CFU-F’s).

Materials and Methods

Study design

In this prospective and randomized clinical trial we evaluated 24 consecutive patients (25 hips) with non-traumatic FHN during a period of two years after intervention. All patients signed the informed consent, the institutional review board of the hospital approved the study; all procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The inclusion criteria for this study were age over 18 years and the presence of stage II femoral head osteonecrosis according to the Association of Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) classification. Before inclusion into the study all patients were evaluated with two plane radiographs and an MRI of the affected hip. At the day of the procedure patients were randomized in two groups using a simple randomization method based upon sequential patient allocation: core decompression only vs. core decompression with the application of BMAC. For clinical outcome the VAS and HHS were measured. For radiological outcome the volume of the necrotic zone and the stage according to ARCO classification was evaluated with an MRI. The subsequent course of osteonecrosis was evaluated at 12 and 24 months postoperatively. This study was approved by the ethics committee of University of Heidelberg, Germany.

Core decompression procedure

In all patients a core decompression procedure was performed under general anesthesia. Under the guidance of an image intensifier in two planes, three 2.0 mm K-wires (Kirschner wires) were drilled through the major trochanter and along the femoral neck axis into the femoral head, reaching the subchondral necrotic area (2-3 mm from the articular cartilage). The most centrally placed K-wire in the necrotic zone was over drilled using 5 mm trephine as has been previously described in the literature.

Bone marrow aspiration, processing and instillation

The harvesting of autologous bone marrow was performed by percutaneous aspiration from the ventral iliac crest (both sides) using a bone marrow biopsy device. The initial volume of harvested marrow was 200 to 220 mL. Intra-operative processing and concentration of stem cells was performed using a Sepax centrifugation device from Biosafe SA (Eysins, Switzerland) with a volume reduction protocol that isolates the nucleated cell (NC) fraction in the buffy coat. After cell segregation, the erythrocytes, nucleated cells and plasma were automatically decanted. 12 mL of bone marrow concentrate suspension was isolated. 2 mL of the final cell concentrate volume (BMAC) was collected for further experimental investigations. 10 mL of BMAC was instilled into the necrotic zone through the canulated trephine drill after removal of the central k-wire.

In vitro analysis of mesenchymal stem cells

The number of MSCs within the native bone marrow and the bone marrow concentrate was analyzed using the CFU-F’s. Assuming that each adherent MSC is able to form a fibroblast colony, the number of MSCs within a cell culture could be estimated. Per donor, 2×106 mononucleated cells (MNC) out of the native bone marrow and the BMAC were seeded into three T25 tissue culture flasks each and cultured in standard medium consisting of high glucose DMEM, 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10 ng/mL recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 10 ng/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). After seven days of culturing, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 70 % ethanol stained with toluidin blue. Fibroblast colonies were counted manually using a microscope at 25th magnification. (Modified protocol from Castro-Malaspina et al; 1980).6

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean or mean ± SEM. The nominal data of patients’ characteristics were tested using the test and χ2 Fisher exact test. The distribution of continuous data was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the appropriate parametric or non-parametric test was selected. Differences within the groups for radiological and clinical outcome data were compared with the Wilcoxon test and between the groups – with Mann-Whitney test. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. For radiological evaluation MRI scans of 25 hips before surgery, 20 hips at 1 year and 15 hips at 2 years after operation were available due to the presence of endoprosthesis and other reasons. For longitudinal and transverse comparison of the volume of the osteonecrosis, only data of patients with full radiological observation was analyzed. Calculation of FHN volume was performed using GE Healthcare RIS/PACS software (Milan, Italy). SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Graph Pad Prism software (Graph Pad, La Jolla, CA, USA) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Twenty-five hips of 24 patients with femoral head osteonecrosis were included into this study between 2008 and 2010 and assigned by random to the treatment method (14 in control group, 11 in verum group). All 25 hips were fully evaluated clinically (VAS: preoperatively, 3 months postoperatively, 1 and 2 years after treatment; HHP: preoperatively, 3 months, 1 and 2 years after treatment) and if feasible evaluated radiographically (MRI preoperatively, 1 and 2 years after treatment). Both study populations did not significantly differ in age, gender, side of FHN and risks factors for osteonecrosis (steroid therapy in the patients’ history) as shown in Table 1. According to the inclusion criteria all patients suffered from an ARCO II FHN and had no prior trauma. No side effects (hematoma, infection, nerve injury and others) either from the bone marrow aspiration from the pelvic rim or from the injection into the femoral head were observed during the entire study period.

Table 1.

Relevant clinical characteristics of patients with femoral head necrosis before operative procedure.

| Characteristics | CD (n=14) | CD with BMAC (n=11) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.5±3.3 | 44.3±3.4 | n.s. |

| Gender (m/f) | 12/2 | 10/1 | n.s. |

| Side (left/right) | 8/6 | 6/5 | n.s. |

| Chemotherapy | 2 | 0 | n.s. |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | 3 | 1 | n.s. |

CD, core decompression; BMAC, bone marrow aspiration concentration; n.s., not significant.

Clinical and functional outcome

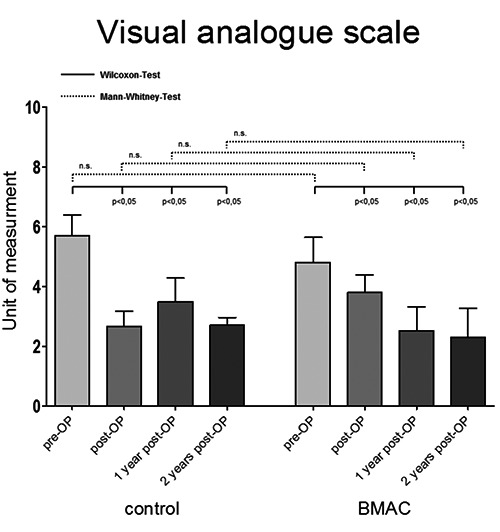

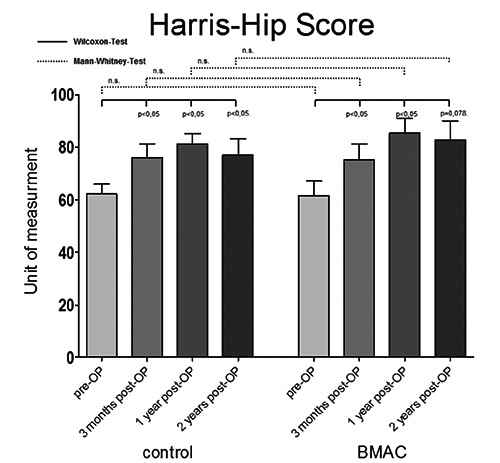

The clinical and functional outcome was measured using standardized scores (VAS; HHS). At the time of inclusion into the study there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding pain and function. Postoperatively, significant decrease in pain associated with a functional benefit lasting the entire observation period was observed. However, there was no difference in the clinical outcome between the two study groups (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Pre- and postoperative outcome of patients referring to visual analogue scale after core decompression vs. core decompression with bone marrow aspirated and concentrated application (BMAC). Significance value P<0.05; n.s., not significant.

Figure 2.

Pre- and postoperative functional outcome of patients measured with Harris-Hip Score after core decompression vs. core decompression with bone marrow aspirated and concentrated application (BMAC). Significance value P<0.05; n.s., not significant.

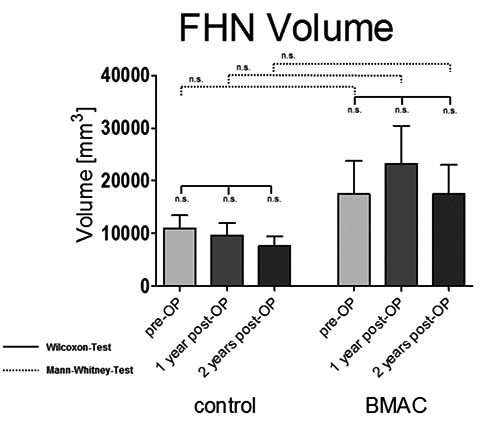

Radiological outcome

Before treatment there was no significant difference between the mean volumes of the osteonecrosis in both groups. In contrast to the clinical outcome, we could not perceive any significant change in the volume of FHN in both treatment groups related to the longitudinal course after treating (Figure 3). Again no statistically significant difference was detected between the groups. FHN progressing to ARCO III or IV was defined as failure of the treatment. This includes all patients with joint replacement (total hip arthroplasty) due to the FHN within two years in both groups. Over the period of two years there was no significant difference between the head survival rate of 8/14 (57%) in the control group, and 7/11 (64%) in the verum group. There was no difference between the two groups with regard to the interval between core decompression with or without BMAC application and THA.

Figure 3.

Pre- and postoperative femoral head necrosis (FHN) volume of patients after core decompression vs. core decompression with bone marrow aspirated and concentrated application (BMAC). Significance value P<0.05; n.s., not significant.

Bone marrow

The bone marrow was analyzed before and after the centrifugation procedure using the Sepax centrifugation device. Table 2 shows the significant increase in the number of nucleated cells due to the centrifugation step. Additionally, the number of CFU that best represents the number of MSC shows a significant increase (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of nucleated cells and CFU within the bone marrow of verum group patients before and after processing using SEPAX centrifugation device.

| Parameters | Native | SEPAX | Concentration | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear cells (106 cells/mL) | 18.9±3.1 | 118.9±15.1 | 6,3-fold | <00001 |

| f-CFU (20%FCS/2Mio) | 33.0±9.5 | 50.0±15.9 | 1,5-fold | <0.0178 |

f-CFU, colony forming units.

Discussion

Femoral head necrosis is a painful disease usually afflicting young male patients and the natural course of this disease tends to be progressive and ends in secondary osteoarthritis.7 In late stage osteonecrosis (ARCO III and IV), total hip arthroplasty (THA) currently seems to be the best treatment with good functional restoration. However, the young patient age and subsequent expected life span is substantially longer than the currently expected longevity of primary THA. Early recognition of FHN and lastly established less invasive treatment modalities open new possibilities to treat this disease for preservation of the spherical femoral head shape indicating a better outcome and finally,8 avoiding THA. One of these operations is the core decompression procedure9-11 and the literature indicates that it is superior to non-operative therapy.12,13 It has been shown that core decompression leads to significant post-operative pain reduction in early stage FHN.2,14 Nevertheless, in postoperative MRI and patho-morphologic trials it could be shown that no significant repair process in the necrotic area of FHN could be achieved with core decompression alone,15 making it a controversial procedure and calling for additional alternative treatment options. The long term results of this procedure are mainly influenced from the initial stage of the osteonecrosis with best prognosis for ARCO I and worst for ARCO III and IV. The outcome of the non-reversible early stage ARCO II is still under discussion. Therefore we included ARCO II hips in this study only.

The injection of mesenchymal progenitor cells into the osteonecrosis seems to improve the outcome of FHN as shown by Hernigou et al.16 The application of ex vivo cultivated stem cells for treatment of diseases of the musculoskeletal system is possible, but currently requires advanced laboratory and technical effort. In addition, this two-step procedure is associated with a higher risk of complications and higher costs. On the other hand, cell therapy systems using centrifugation steps were recently developed which permit intra-operative enrichment of mesenchymal progenitor cells from BMAC simultaneously at the time of core decompression followed by application of the BMAC into the necrotic area of FHN at the end of the same procedure. Simultaneous application of BMAC is praised as an encouraging approach. Hernigou et al. (2002, 2005) inaugurated this treatment option and published a large patient series, that demonstrates an obvious improvement in the head survival rate compared to other literature data with core decompression only.5,16 Lastly, Civinini et al. showed good results of treating early stage femoral head necrosis using injectable calcium and sulphate/calcium bioceramic with bone marrow concentrate.17

The first aim of our investigation was to evaluate the safety of the additional aspiration and injection of autologous bone marrow. In our study we did not encounter any complications resulting from this method of bone marrow transplantation. In particular, there were no infections, excessive new bone formation or tumor induction and there were no local complications at the harvesting side. These findings are in line with published data showing the very low risk of this one step procedure.18

The second aim of our study is the effect of the additional injection of BMAC into the femoral head on the clinical and radiological outcome. We found that significant pain relief and functional improvement could be achieved in both groups at the 2 year follow up independent of the operative procedure (core decompression or core decompression with BMAC application). There are a limited number of studies evaluating pain and functional gain after core decompression, and a direct comparison with these studies is difficult. Rajagopa et al. performed a systematic review of four studies evaluating core decompression of femoral head necrosis and its effect on pain and function of the hip over a minimum of two years postoperatively.19 The results of their analysis showed a variable gain of function after core decompression procedure. One of the articles quoted demonstrated a significant improvement in hip function,20 a second one just moderate improvement21 and two other studies only minor, or no improvement.22,23 Our study supports the latter. We did not note any significant differences relating to pain or functional state of patients between both groups, supporting the hypothesis, that additional BMAC application after core decompression provides no benefit to patients with FHN at this time. This finding seems to be in contrast to the studies of Hernigou et al. However, the study presented here was set up as a randomized controlled trial with restrictive inclusion criteria (ARCO II only). The rejection of ARCO I patients with a better prognosis might, at least in part, explain differences to the results of Hernigou et al. and other studies. Table 3 shows a comparison of head survival rate of this study and recently published studies using BMAC or similar bone marrow treatment options in femoral head necrosis. Because of different study protocols, meaningful comparison of these research findings is limited.

Table 3.

A comparison of head survival rates at two to five years after core decompression and BMAC (bone marrow aspiration and concentration) application or similar bone marrow treatment options in femoral head necrosis in recently published studies.

| Literature (year) | ARCO | Survival rate verum | Survival rate control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hernigou et al.33 (2002) | I-III* | 155/189 (82%) | No control | - |

| Gangji et al.40 (2004) | I-II | 9/10 (90%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0.016 |

| Gangji et al.41 (2011) | I-II | 10/13 (77%) | 3/11 (27%) | <0.05 |

| Zhao et al.10 (2012) | I-II | 51/53 (96%) | 34/44 (77%) | <0.05 |

| This study (2015) | II | 7/11 (64%) | 8/14 (57%) | >0.05 |

ARCO, Association Research Circulation Osseus.

*Hernigou et al. used Steinberg classification for recruiting patients in his study (Steinberg I-IV).

A study with a protocol similar to ours was published by Gangji et al.24 They presented the results of a randomized and prospective clinical trial of ARCO I-II patients treated with core decompression only vs. core decompression with autologous bone marrow application. Femoral head survival rate of this study is also mentioned in Table 3. Gangji et al. also describe an increased head survival rate in the BMAC group. Although this is a randomized controlled prospective trial, there are some principal limitations to this study: there is a short follow-up period (two years) and there are a small number of patients in both study groups. The small study population is a result of the prospective design and very restrictive inclusion criteria of FHN patients (ARCO II only). In comparison to the study presented by Hernigou et al.,16 the major advantage of this study is the comparison of a BMAC group with a control group, thereby increasing explanatory power.

Conclusions

Femoral head necrosis with a spherical head and irreversible necrosis of the bone (ARCO II) profits from core decompression. In contrast to previous series the current study excluded ARCO I stages of FHN which can regenerate on its own, and inclusion of ARCO I makes interpretation of drilling of this stage difficult. This trial of 25 hips could not detect a benefit from the additional injection of bone marrow concentrate with regard to bone regeneration and clinical outcome in the short term. Further studies of BMAC properties with a larger sample size and longer follow-up are needed to better validate our results and possibly modify our procedure.

References

- 1.Gangji V, Toungouz M, Hauzeur JP: Stem cell therapy for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2005;5:437-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mont MA, Hungerford DS. Non-traumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:459-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao D, Cui D, Wang B, et al. Treatment of early stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head with autologous implantation of bone marrow-derived and cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Bone 2012;50:325-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasten P, Beyen I, Egermann M, et al. Instant stem cell therapy: characterization and concentration of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Eur Cell Mater 2008;16:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernigou P, Poignard A, Manicom O, et al. The use of percutaneous autologous bone marrow transplantation in nonunion and avascular necrosis of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:896-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro-Malaspina H, Gay RE, Resnick G, et al. Characterization of human bone marrow fibroblast colony-forming cells (CFU-F) and their progeny. Blood 1980;56:289-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Issa K, Pivec R, Kapadia BH, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: the total hip replacement solution. Bone Joint J 2013;95B:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Osteonecrosis: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004;16:443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman JR, Berry DJ, Mont MA, et al. Osteonecrosis of the hip: management in the 21st century. Instr Course Lect 2003;52:337-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg ME, Steinberg DR. Classification systems for osteonecrosis: an overview. Orthop Clin North Am 2004;35:273-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ficat RP. Idiopathic bone necrosis of the femoral head. Early diagnosis and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985;67:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mont MA, Carbone JJ, Fairbank AC. Core decompression versus nonoperative management for osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996:169-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koo KH, Kim R, Ko GH, et al. Preventing collapse in early osteonecrosis of the femoral head. A randomised clinical trial of core decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995;77:870-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider W, Breitenseher M, Engel A, et al. [The value of core decompression in treatment of femur head necrosis]. Orthopade 2000;29:420-9. [Article in German]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plenk H, Jr., Hofmann S, Breitenseher M, Urban M. [Pathomorphological aspects and repair mechanisms of femur head necrosis]. Orthopade 2000;29:389-402. [Article in German]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernigou P, Beaujean F. Treatment of osteonecrosis with autologous bone marrow grafting. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002:14-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Civinini R, De Biase P, Carulli C, et al. The use of an injectable calcium sulphate/calcium phosphate bioceramic in the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Int Orthop 2012;36:1583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrich C, Franz E, Waertel G, et al. Safety of autologous bone marrow aspiration concentrate transplantation: initial experiences in 101 patients. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2009;1:e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopal M, Balch Samora J, Ellis TJ. Efficacy of core decompression as treatment for osteonecrosis of the hip: a systematic review. Hip Int 2012;22:489-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell ET, Lanzer WL, Mankey MG. Core decompression for early osteonecrosis of the hip in high risk patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997:181-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavernia CJ, Sierra RJ. Core decompression in atraumatic osteonecrosis of the hip. J Arthroplasty 2000;15:171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito S, Ohzono K, Ono K. Joint-preserving operations for idiopathic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Results of core decompression, grafting and osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniwa S, Nishikori T, Furukawa S, et al. Evaluation of core decompression for early osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000;120:241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gangji V, De Maertelaer V, Hauzeur JP. Autologous bone marrow cell implantation in the treatment of non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: five year follow-up of a prospective controlled study. Bone 2011;49:1005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]