Abstract

Kinetochores are macromolecular machines that drive eukaryotic chromosome segregation by interacting with centromeric DNA and spindle microtubules. While most eukaryotes possess conventional kinetochore proteins, evolutionarily distant kinetoplastid species have unconventional kinetochore proteins, composed of at least 19 proteins (KKT1–19). Polo-like kinase (PLK) is not a structural kinetochore component in either system. Here, we report the identification of an additional kinetochore protein, KKT20, in Trypanosoma brucei. KKT20 has sequence similarity with KKT2 and KKT3 in the Cys-rich region, and all three proteins have weak but significant similarity to the polo box domain (PBD) of PLK. These divergent PBDs of KKT2 and KKT20 are sufficient for kinetochore localization in vivo. We propose that the ancestral PLK acquired a Cys-rich region and then underwent gene duplication events to give rise to three structural kinetochore proteins in kinetoplastids.

Keywords: kinetochore, kinetoplastid, Trypanosoma brucei, polo-like kinase, polo box domain, DPB

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic chromosome segregation is directed by the kinetochore, the macromolecular protein complex that assembles onto centromeric DNA and captures spindle microtubules during mitosis and meiosis [1,2]. The kinetochore is a highly complicated structure that consists of more than 30 different structural proteins even in a simple budding yeast kinetochore [3]. It is thought that most eukaryotes use these proteins to build kinetochores because of their conservation in diverse eukaryotes [4–7]. However, none of these conventional kinetochore components has been found in kinetoplastids, a group of evolutionarily distant eukaryotes that include medically important pathogens such as Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania [8]. These organisms instead have unconventional kinetochores, composed of at least 19 proteins named KKT1–19 (kinetoplastid kinetochore protein) [7]. Their sequence analyses failed to identify orthologous proteins in other organisms, suggesting that kinetoplastid kinetochores may have a distinct evolutionary origin [7]. The evolutionary origins of KKT proteins are not known.

Polo-like kinases (PLKs) are Ser/Thr kinases that regulate cell cycle progression, centriole biogenesis, kinetochore functions, cytokinesis, the DNA damage response and neuronal activity [9–12]. PLKs consist of an N-terminal kinase domain and C-terminal polo box domain (PBD) [13]. PLKs carry out diverse functions by phosphorylating numerous substrates, where specificity comes in part from the PBD that governs the localization of PLKs in space and time. The PBDs are protein–protein interaction domains that require priming phosphorylation [14], although phosphorylation-independent interactions are also possible [15]. PLK1 is known to localize at the kinetochore, interact with kinetochore/checkpoint proteins and regulate kinetochore functions in some eukaryotes [16–19]. However, it is not a structural kinetochore component in any organism studied thus far, and there is no report of a kinetochore protein that contains a PBD [20].

Here we report the identification of a previously unidentified kinetochore protein in T. brucei and discuss how it defines a family of three kinetoplastid kinetochore proteins that might have evolved from PLK.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of KKT20 in Trypanosoma brucei

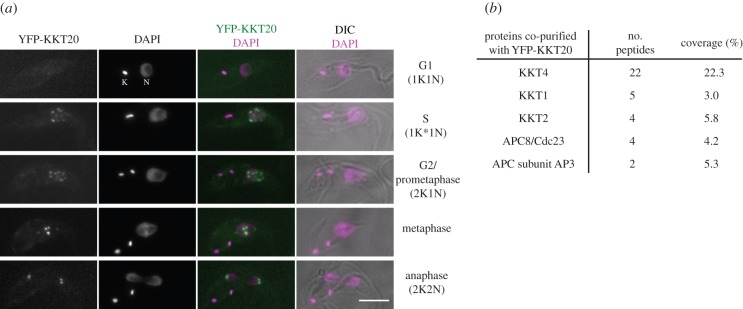

To understand the design principle of kinetoplastid kinetochores, it is essential to obtain a complete list of kinetochore components. We previously performed immunoprecipitation of the YFP-tagged version of KKT proteins in T. brucei and identified co-purifying proteins by mass spectrometry. Subsequent YFP tagging of candidate proteins led to the identification of 19 kinetochore proteins, named KKT1–19 [7]. KKT4 was unique among the 19 proteins, because KKT4, not other KKT proteins, co-purified with significant amounts of APC/C subunit proteins. Because the complete list of APC/C components in T. brucei remained unclear until recently [21], we thought that those proteins that were uniquely identified in the KKT4 immunoprecipitation sample may well be as-yet unidentified APC/C components. However, one such protein (ORF Tb927.8.4760) had typical kinetochore localization in vivo (figure 1a). We named this protein KKT20. Unlike KKT4, which localized at the kinetochore throughout the cell cycle, KKT20 localized from S phase until the end of anaphase (figure 1a). Mass spectrometry of proteins that co-purified with YFP-KKT20 confirmed its interaction with several KKT proteins, among which KKT4 was the most significant hit (figure 1b). In addition, some APC/C subunits were detected. Together with our previous result that KKT20 and APC/C subunits were detected only in the KKT4 sample, it is likely that KKT20 and KKT4 are in close proximity at the kinetochore. Supporting this possibility, KKT20 had weak spindle-like signal near the poles during metaphase (figure 1a), which was observed for KKT4 but not any other KKT protein [7].

Figure 1.

Identification of KKT20. (a) YFP-KKT20 localizes at kinetochores from S phase until the end of anaphase. Examples of trypanosome procyclic cells expressing YFP-KKT20 are shown. K and N stand for the kinetoplast and nucleus, respectively. Note that there are weak spindle-like signals near the poles besides kinetochore dots during metaphase. K* denotes an elongated kinetoplast. Scale bar, 5 µm. (b) YFP-KKT20 MS summary table. See electronic supplementary material, table S1 for all proteins identified by MS.

2.2. KKT20 has similarity to KKT2 and KKT3

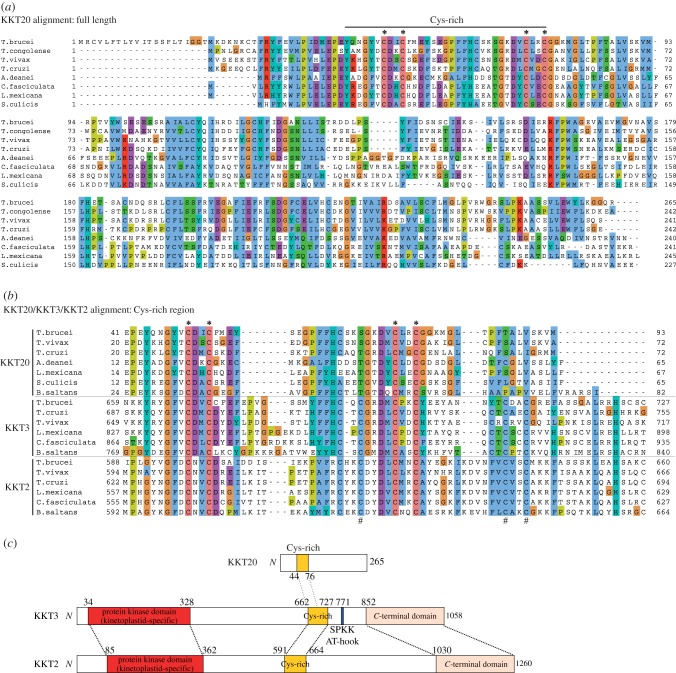

KKT20 is conserved among kinetoplastids and has four conserved Cys residues (figure 2a). Cys-rich motifs are present in hundreds of proteins in eukaryotic genomes [22], including two homologous KKT proteins, KKT2 and KKT3, in kinetoplastids [7]. Interestingly, PSI-BLAST search using T. brucei KKT20 on non-redundant protein sequence database containing proteome from numerous organisms collected KKT20 homologues in the first iteration and then identified the KKT3 proteins from Trypanosoma rangeli and Trypanosoma grayi in the second iteration, revealing similarity in the Cys-rich region. A similar result was obtained for T. cruzi KKT20, suggesting that the KKT20's Cys-rich region apparently has a higher level of similarity to KKT3's Cys-rich region than to other proteins. Alignment of KKT20/KKT3/KKT2 revealed that KKT20's four conserved Cys residues are also present in KKT3 and KKT2 (figure 2b, indicated by asterisk). In addition to these four Cys, KKT3 and KKT2 have several additional conserved Cys residues (figure 2b, indicated by hash). These results revealed that KKT20 has similarity to KKT3 and KKT2 at least in the Cys-rich region (figure 2c).

Figure 2.

KKT20 has similarity to KKT2 and KKT3 in the Cys-rich region. (a) Multiple alignment of KKT20 reveals four Cys residues conserved among kinetoplastids (indicated by asterisk). (b) Multiple alignment of KKT20/KKT3/KKT2 in the Cys-rich region shows the conservation of some Cys residues in all three proteins (denoted by asterisk), as well as several additional Cys conserved in KKT2 and KKT3, not KKT20 (denoted by hash). (c) Schematic of T. brucei KKT20, KKT3 and KKT2 proteins, showing similarity in the Cys-rich region. KKT2 and KKT3 additionally share similarity in the N-terminal kinase domain and C-terminal domain.

2.3. The C-terminal domain of KKT20, KKT2 and KKT3 has similarity to the polo box domain

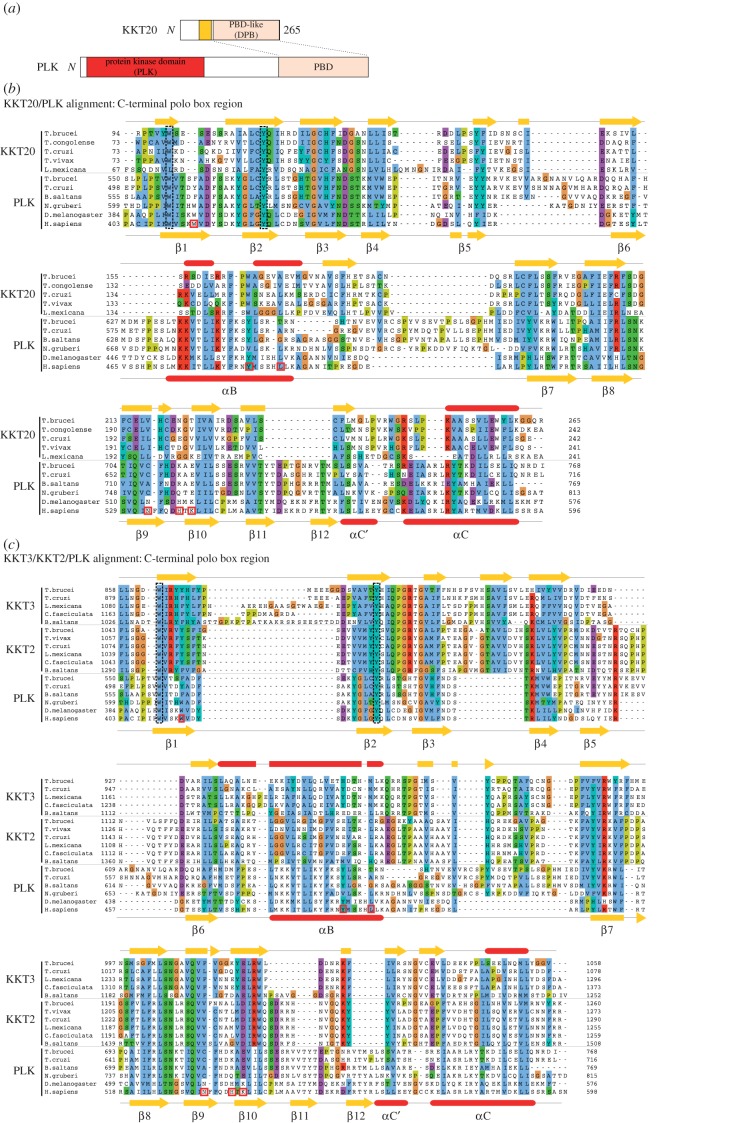

We then performed sensitive profile sequence searches using hidden Markov models [23,24]. To our surprise, a Jackhmmer search using T. brucei KKT20 identified the PLK from Candida tenuis (Fungi) in the second iteration (E-value < 10−2). A similar search using Trypanosoma congolense KKT20 hit the PLK from Trichoplax adhaerens (Metazoa). KKT20 does not have a kinase domain and the similarity was found between KKT20's C-terminal region and the polo boxes of these PLKs (figure 3a). Similar results were obtained using HHpred that allows profile-to-profile comparison [25], where the highest level of similarity was found for T. congolense KKT20 against polo boxes (pfam PF00659: probability 0.96, E-value < 10−2). Furthermore, secondary structure predictions revealed similarity between KKT20's C-terminal region and polo boxes (figure 3b). These results showed that the C-terminal region of KKT20 has weak but significant similarity to PBD.

Figure 3.

The C-terminal domain of KKT20/KKT2/KKT3 has similarity to the PBD. (a) Schematic of KKT20 and PLK, showing similarity in the C-terminal region. (b) Multiple alignment of the C-terminal domain of KKT20 and PLK PBDs with their secondary structure predictions reveals significant similarity between them. T. brucei KKT20 (top) and H. sapiens PLK1 (bottom) structural predictions were derived from PSIPRED. The fold nomenclature of H. sapiens PLK1 is based on [14], and the residues critical for phosphopeptide binding are shown in red boxes. (c) Multiple alignment of the C-terminal domain of KKT3/KKT2 and PLK PBDs with secondary structure predictions for T. brucei KKT3 (top) and H. sapiens PLK1 (bottom). Highly conserved residues that were mutated in this study are highlighted by black dotted boxes.

KKT2 and KKT3 have three domains conserved among kinetoplastids: a protein kinase domain, a central domain containing Cys-rich region and a C-terminal domain (figure 2c) [7]. Although KKT20 has similarity to KKT2/KKT3 in the Cys-rich region, we could not detect significant similarity elsewhere using PSI-BLAST or HMMER (figure 2c). However, a Jackhmmer search using the KKT2 C-terminal domain from Bodo saltans collected KKT2 homologues in the first iteration, KKT3 homologues in the second, and then detected Leishmania PLKs in the third iteration (E-value < 10−2). Furthermore, similar searches using the C-terminal domains of KKT2 from other kinetoplastids or KKT3 consistently revealed marginal (but non-significant) sequence similarity to PLKs from various eukaryotes. None of these searches hit KKT20, consistent with the lack of significant sequence similarity between KKT20 and KKT2/KKT3 except in the Cys-rich region. Again, structural predictions revealed similar secondary structures between KKT2/KKT3's C-terminal domain and polo boxes (figure 3c). Therefore, like KKT20, KKT2/KKT3 also have a domain that has weak similarity to polo boxes. We propose to call the C-terminal domain of KKT20/KKT2/KKT3 the divergent polo box (DPB) domain.

2.4. Isolated divergent polo box domains of KKT2 and KKT20 are sufficient for kinetochore localization

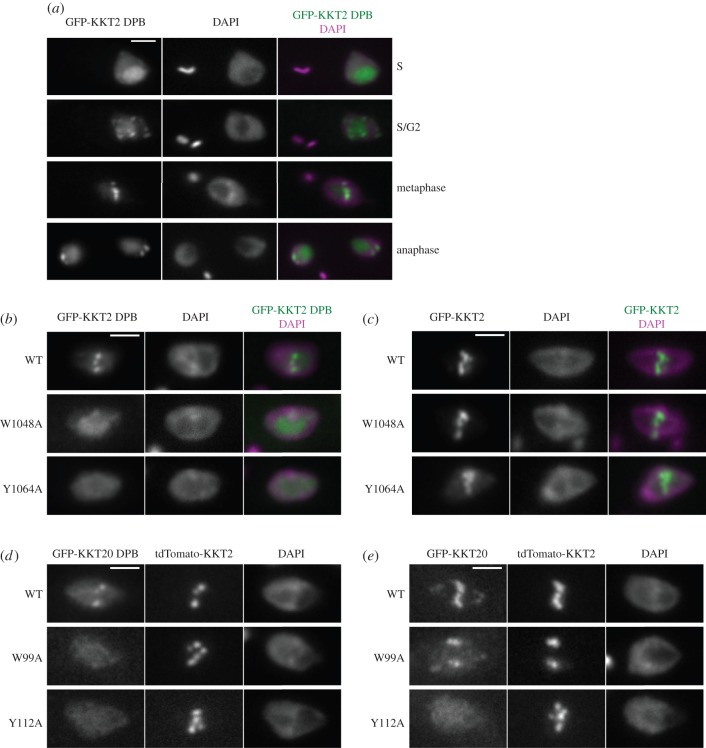

To investigate the role of DPB domains, we ectopically expressed the GFP–NLS fusion proteins in trypanosomes. We found that KKT2 DPB (residues 1024–1260) had typical kinetochore localization during G2 and mitosis (figure 4a), showing that the isolated DPB domain of KKT2 is sufficient for mediating kinetochore localization, presumably through interaction with other kinetochore proteins. We then mutated some residues conserved in both DPB domains and PBDs (highlighted by black dotted boxes in figure 3c). The resulting KKT2 DPBW1048A and KKT2 DPBY1064A mutants did not localize at kinetochores (figure 4b), suggesting that these conserved residues are important for its function.

Figure 4.

Isolated DPB domains of KKT2 and KKT20 can localize at kinetochores. (a) KKT2 DPB has kinetochore localization in G2, metaphase and anaphase. (b,c) W1048A and Y1064A mutations abolish the kinetochore localization of KKT2 DPB (b) but not the full-length protein (c). (d) KKT20 DPB localizes at kinetochores, which is abolished in W99A and Y112A mutants. Note that KKT20 DPB co-localizes with tdTomato-KKT2. (e) The Y112A mutation, but not W99A, abolishes the kinetochore localization of the full-length KKT20 protein. For (a–e), inducible GFP–NLS fusion proteins were expressed with 10 ng ml−1 doxycycline for 1 day. Scale bars, 2 µm.

In contrast to the DPB domain of KKT2, which localizes at kinetochores starting from G2 phase, full-length KKT2 localizes throughout the cell cycle [7] (data not shown). Furthermore, mutating the conserved residues in DPB did not abolish the kinetochore localization of the full-length protein (KKT2W1048A and KKT2Y1064A; figure 4c). These results suggest that KKT2 possesses other region(s) that promote its kinetochore localization, which is in line with the presence of putative DNA-binding motifs in the central region [7].

We did not observe any kinetochore localization for the DPB of KKT3 (residues 831–1058; data not shown). The KKT20 DPB (residues 83–265) had marginal kinetochore localization, which was abolished when highly conserved residues were mutated (KKT20-DPBW99A and KKT20-DPBY112A; figure 4d). The Y112A mutation (not W99A) also abolished the localization of the full-length protein (figure 4e), suggesting that the DPB plays a major role in promoting the kinetochore localization of KKT20. Taken together, these data provide functional evidence for the DPB domains of KKT2 and KKT20.

3. Discussion

This study revealed that three kinetoplastid kinetochore proteins (KKT2, KKT3 and KKT20) have a divergent PBD that is distantly related to the PBDs of PLKs. Bona fide PLK is present in kinetoplastids [26,27]. In T. brucei, PLK is known to play critical functions for basal body biogenesis and cytokinesis but is not known to localize at the kinetochore or regulate kinetochore functions [28–30]. The PBDs in kinetoplastid PLKs do not have residues that are crucial for phosphopeptide binding in human PLK1 [14], and it remains unknown whether they interact with other proteins in a phospho-dependent manner [31,32]. The DPBs of KKT20/KKT2/KKT3 also lack these residues (figure 3b,c). In the future, it will be important to identify their interaction partners (if any) and reveal the mechanism of interaction to shed light into the function of these proteins.

Besides the DPB domains, KKT20 and KKT2/KKT3 also have similarity in the Cys-rich region, suggesting that these proteins may share common ancestry. KKT2 and KKT3 additionally have an N-terminal kinase domain that does not have clear affiliation to any known kinase group [33]. Given the notion that PLK was present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor [34], we speculate the following scenario as a possible evolutionary origin of KKT2/KKT3/KKT20: PLK (or an ancestor of PLK) that had an N-terminal kinase domain and C-terminal polo boxes acquired a Cys-rich region in the middle. This ancestor highly diverged in amino acid sequences, so that the kinase domain looks unique among eukaryotic kinases, and underwent gene duplication to give rise to KKT2 and KKT3. These proteins in some kinetoplastids additionally acquired DNA-binding motifs such as AT-hook and SPKK, possibly to enhance their interaction with centromeric DNA [7]. While all three proteins retained the Cys-rich region and the DPB domain, KKT20 lost a kinase domain at some point. Now, these three proteins appear to perform distinct functions, judging from their distinct interaction profiles and localization patterns [7].

Gene duplication is thought to be a major mechanism to generate new functions using pre-existing proteins [35]. In non-kinetoplastid eukaryotes, the following structural modules are present in kinetochore proteins and spindle checkpoint proteins: the RWD domain in Spc24/Spc25, Ctf19/Mcm21, Csm1, Mad1 and KNL1 [36–39], CH domain in Ndc80/Nuf2 [40–42], TPR domain in Bub1/BubR1 and Mps1 [43,44], and histone-fold domain in CENT-T/W/S/X and CENP-A [45–47]. This suggests that the highly complicated present-day kinetochores originated from a small number of protein modules aided by gene duplication. So far, we could not detect any of these domains in the 20 kinetoplastid kinetochore proteins, consistent with the possibility that the kinetoplastid kinetochores have a distinct evolutionary origin [7]. The presence of kinetochore proteins that have DPB domains in kinetoplastids, but not in other eukaryotes, further supports this possibility. Nonetheless, gene duplication products are found in kinetoplastid kinetochores, namely KKT17/KKT18, KKT10/KKT19 and KKT2/KKT3/KKT20, highlighting the importance of gene duplication in the invention of macromolecular complexes.

4. Material and methods

4.1. Cells

All cell lines used in this study were derived from T. brucei SmOxP927 procyclic form cells (TREU 927/4 expressing T7 RNA polymerase and the tetracycline repressor to allow inducible expression) [48]. Cells were grown at 28°C in SDM-79 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum [49]. Endogenous YFP tagging was performed using the pEnT5-Y vector [50], with the following primers: BA887 and BA888 for 247 bp starting at the second codon of KKT20 coding sequence, and BA889 and BA890 for 250 bp of 5′ UTR. These two DNA fragments amplified from genomic DNA were ligated into pEnT5-Y cut with XbaI and BamHI restriction sites, making pBA463. Endogenous tdTomato tagging of KKT2 was performed by subcloning the KKT2 targeting sequence of pBA67 into pBA148 using XbaI and BamHI restriction sites, making pBA164 [7].

To make pBA310 (inducible expression vector with GFP–NLS), a synthetic DNA fragment that has an NLS sequence from La protein (RGHKRSRE) [51] and multiple cloning sites (made by annealing BA680 and BA681) was ligated into pDEX777 cut with XbaI and BamHI. Full-length KKT2 (pBA425: amplified from genomic DNA with BA763 and BA768), KKT2 DPB1024–1260 (pBA736: BA1159 and BA768) and KKT3 DPB831–1058 (pBA366: BA619 and BA620) were ligated into pBA310 cut with BamHI and AflII, whereas full-length KKT20 (pBA747: BA985 and BA988) and KKT20 DPB83–265 (pBA748: BA1157 and BA988) were ligated into pBA310 cut with PacI and AscI. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using Phusion polymerase and the following primers: KKT2W1048A (BA1292 and BA1293), KKT2Y1064A (BA1294 and BA1295), KKT20W99A (BA1296 and BA1297) and KKT20Y112A (BA1298 and BA1299). All constructs were sequence verified.

Plasmids linearized by NotI were transfected to trypanosomes by electroporation into an endogenous locus (pBA463 and pBA164) or 177 bp repeats on minichromosomes (pBA310 derivatives). Transfected cells were selected by the addition of 25 µg ml−1 hygromycin (pBA463), 10 µg ml−1 blasticidin (pBA164) or 5 µg ml−1 phleomycin (pBA310 derivatives). The expression of GFP–NLS fusion proteins (pBA310 derivatives) was induced by the addition of doxycycline (10 ng ml−1) for 1 day. All cell lines, plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in electronic supplementary material, tables S3, S4 and S5, respectively.

4.2. Fluorescence microscopy

For the analysis of fluorescently tagged proteins, cells were washed once with PBS, settled onto glass slides and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% NP-40 in PBS for 5 min and embedded in mounting media (1% w/v 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane, 90% glycerol, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 8.0) containing 100 ng ml−1 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI). Images were captured on a DeltaVision fluorescence microscope (Applied Precision) installed with softWoRx v. 5.5 housed in the Oxford Micron facility. Fluorescent images were captured with a CoolSNAP HQ camera and processed in ImageJ [52]. Cell cycle stages of individual cells were estimated as described previously [53,54].

4.3. Immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry

Immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry were performed essentially as described previously [7] except that a Q-Exactive (Thermo Scientific) at the Central Proteomics Facility (www.proteomics.ox.ac.uk, University of Oxford) was used and that peptides were identified with Mascot (Matrix Science). Proteins identified with at least two peptides were considered and shown in electronic supplementary material, table S1. Raw MS data are available upon request.

4.4. Bioinformatics

PSI-BLAST search was done on non-redundant protein sequences database (all non-redundant GenBank CDS translations + PDB + SwissProt + PIR + PRF excluding environmental samples from WGS projects, 14 July 2015), using default setting [55]. Jackhmmer search (v. 3.0) was done on UniProt reference proteomes, using default setting (E-value cut-off 0.01) [24]. HHpred was carried out using pfamA_28.0 HMM database [25]. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with MAFFT (L-INS-i method, v. 7) [56] and visualized with ClustalX colouring scheme in Jalview (v. 2.8) [57]. Secondary structure predictions were performed using PSIPRED (v. 3.3) [58]. Accession numbers for protein sequences retrieved from TriTryp database [59–61], GeneDB [62,63], NCBI database [64] or GenBank [65] are listed in electronic supplementary material, table S2.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Francis Barr and Sue Biggins for comments on the manuscript. We also thank Central Proteomics Facility, Benjamin Thomas and Svenja Hester for mass spectrometry analysis, as well as Micron Oxford Advanced Bioimaging Unit. We declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

A supplementary Excel file has the list of YFP-KKT20 MS/MS hits (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

A supplementary PDF file has accession numbers for protein sequences (electronic supplementary material, table S2), cell lines (electronic supplementary material, table S3), plasmids (electronic supplementary material, table S4) and primer sequences (electronic supplementary material, table S5) used in this study.

Author's contributions

O.O.N. performed experiments for figure 4. B.A. performed experiments for figures 1–4 and wrote the manuscript. Both authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

B.A. was supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (grant no. 098403/Z/12/Z), as well as a Wellcome-Beit Prize Fellowship (grant no. 098403/Z/12/A).

References

- 1.Santaguida S, Musacchio A. 2009. The life and miracles of kinetochores. EMBO J. 28, 2511–2531. (doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.173) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheeseman IM. 2014. The kinetochore. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 6, a015826 (doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a015826) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biggins S. 2013. The composition, functions, and regulation of the budding yeast kinetochore. Genetics 194, 817–846. (doi:10.1534/genetics.112.145276) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meraldi P, McAinsh AD, Rheinbay E, Sorger PK. 2006. Phylogenetic and structural analysis of centromeric DNA and kinetochore proteins. Genome Biol. 7, R23 (doi:10.1186/gb-2006-7-3-r23) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vleugel M, Hoogendoorn E, Snel B, Kops GJPL. 2012. Evolution and function of the mitotic checkpoint. Dev. Cell 23, 239–250. (doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westermann S, Schleiffer A. 2013. Family matters: structural and functional conservation of centromere-associated proteins from yeast to humans. Trends Cell Biol. 23, 260–269. (doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akiyoshi B, Gull K. 2014. Discovery of unconventional kinetochores in kinetoplastids. Cell 156, 1247–1258. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akiyoshi B, Gull K. 2013. Evolutionary cell biology of chromosome segregation: insights from trypanosomes. Open Biol. 3, 130023 (doi:10.1098/rsob.130023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunkel CE, Glover DM. 1988. polo, a mitotic mutant of Drosophila displaying abnormal spindle poles. J. Cell. Sci. 89, 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archambault V, Glover DM. 2009. Polo-like kinases: conservation and divergence in their functions and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 265–275. (doi:10.1038/nrm2653) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Cárcer G, Manning G, Malumbres M. 2011. From Plk1 to Plk5: functional evolution of polo-like kinases. Cell Cycle 10, 2255–2262. (doi:10.4161/cc.10.14.16494) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zitouni S, Nabais C, Jana SC, Guerrero A, Bettencourt-Dias M. 2014. Polo-like kinases: structural variations lead to multiple functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 433–452. (doi:10.1038/nrm3819) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowery DM, Lim D, Yaffe MB. 2005. Structure and function of Polo-like kinases. Oncogene 24, 248–259. (doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208280) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elia AEH, et al. 2003. The molecular basis for phosphodependent substrate targeting and regulation of Plks by the Polo-box domain. Cell 115, 83–95. (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00725-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archambault V, D'Avino PP, Deery MJ, Lilley KS, Glover DM. 2008. Sequestration of Polo kinase to microtubules by phosphopriming-independent binding to Map205 is relieved by phosphorylation at a CDK site in mitosis. Genes Dev. 22, 2707–2720. (doi:10.1101/gad.486808) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang YH, et al. 2006. Self-regulated Plk1 recruitment to kinetochores by the Plk1-PBIP1 interaction is critical for proper chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell 24, 409–422. (doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elowe S, Hümmer S, Uldschmid A, Li X, Nigg EA. 2007. Tension-sensitive Plk1 phosphorylation on BubR1 regulates the stability of kinetochore microtubule interactions. Genes Dev. 21, 2205–2219. (doi:10.1101/gad.436007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinley KL, Cheeseman IM. 2014. Polo-like kinase 1 licenses CENP-A deposition at centromeres. Cell 158, 397–411. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, et al. 2015. Meikin is a conserved regulator of meiosis-I-specific kinetochore function. Nature 517, 466–471. (doi:10.1038/nature14097) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheeseman IM, Desai A. 2008. Molecular architecture of the kinetochore–microtubule interface. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 33–46. (doi:10.1038/nrm2310) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bessat M, Knudsen G, Burlingame AL, Wang CC. 2013. A minimal anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS ONE 8, e59258 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059258) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE. 2001. Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 39–46. (doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00167-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eddy SR. 1998. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn RD, Clements J, Arndt W, Miller BL, Wheeler TJ, Schreiber F, Bateman A, Eddy SR. 2015. HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W30–W38. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkv397) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Söding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. 2005. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W244–W248. (doi:10.1093/nar/gki408) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham TM, Tait A, Hide G. 1998. Characterisation of a polo-like protein kinase gene homologue from an evolutionary divergent eukaryote, Trypanosoma brucei. Gene 207, 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Sayed NM, et al. 2005. Comparative genomics of trypanosomatid parasitic protozoa. Science 309, 404–409. (doi:10.1126/science.1112181) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar P, Wang CC. 2006. Dissociation of cytokinesis initiation from mitotic control in a eukaryote. Eukaryotic Cell 5, 92–102. (doi:10.1128/EC.5.1.92-102.2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammarton TC, Kramer S, Tetley L, Boshart M, Mottram JC. 2007. Trypanosoma brucei Polo-like kinase is essential for basal body duplication, kDNA segregation and cytokinesis. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 1229–1248. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05866.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lozano-Núñez A, Ikeda KN, Sauer T, de Graffenried CL. 2013. An analogue-sensitive approach identifies basal body rotation and flagellum attachment zone elongation as key functions of PLK in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 1321–1333. (doi:10.1091/mbc.E12-12-0846) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Z, Liu Y, Li Z. 2012. Structure-function relationship of the Polo-like kinase in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell. Sci. 125, 1519–1530. (doi:10.1242/jcs.094243) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAllaster MR, et al. 2015. Proteomic identification of novel cytoskeletal proteins associated with TbPLK, an essential regulator of cell morphogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 3013–3029. (doi:10.1091/mbc.E15-04-0219) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons M, Worthey EA, Ward PN, Mottram JC. 2005. Comparative analysis of the kinomes of three pathogenic trypanosomatids: Leishmania major, Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi. BMC Genomics 6, 127 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-6-127) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvalho-Santos Z, Machado P, Branco P, Tavares-Cadete F, Rodrigues-Martins A, Pereira-Leal JB, Bettencourt-Dias M. 2010. Stepwise evolution of the centriole-assembly pathway. J. Cell. Sci. 123, 1414–1426. (doi:10.1242/jcs.064931) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohno S. 1970. Evolution by gene duplication. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei RR, Schnell JR, Larsen NA, Sorger PK, Chou JJ, Harrison SC. 2006. Structure of a central component of the yeast kinetochore: the Spc24p/Spc25p globular domain. Structure 14, 1003–1009. (doi:10.1016/j.str.2006.04.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitzberger F, Harrison SC. 2012. RWD domain: a recurring module in kinetochore architecture shown by a Ctf19–Mcm21 complex structure. EMBO Rep. 13, 216–222. (doi:10.1038/embor.2012.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Sun H, Tomchick DR, Yu H, Luo X. 2012. Structure of human Mad1 C-terminal domain reveals its involvement in kinetochore targeting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6549–6554. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1118210109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrovic A, et al. 2014. Modular assembly of RWD domains on the Mis12 complex underlies outer kinetochore organization. Mol. Cell 53, 591–605. (doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei RR, Al-Bassam J, Harrison SC. 2007. The Ndc80/HEC1 complex is a contact point for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 54–59. (doi:10.1038/nsmb1186) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciferri C, et al. 2008. Implications for kinetochore–microtubule attachment from the structure of an engineered Ndc80 complex. Cell 133, 427–439. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schou KB, Andersen JS, Pedersen LB. 2014. A divergent calponin homology (NN-CH) domain defines a novel family: implications for evolution of ciliary IFT complex B proteins. Bioinformatics 30, 899–902. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt661) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolanos-Garcia VM, et al. 2009. The crystal structure of the N-terminal region of BUB1 provides insight into the mechanism of BUB1 recruitment to kinetochores. Structure 17, 105–116. (doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.10.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nijenhuis W, et al. 2013. A TPR domain-containing N-terminal module of MPS1 is required for its kinetochore localization by Aurora B. J. Cell Biol. 201, 217–231. (doi:10.1083/jcb.201210033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer DK, O'Day K, Trong HL, Charbonneau H, Margolis RL. 1991. Purification of the centromere-specific protein CENP-A and demonstration that it is a distinctive histone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 3734–3738. (doi:10.1073/pnas.88.9.3734) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hori T, et al. 2008. CCAN makes multiple contacts with centromeric DNA to provide distinct pathways to the outer kinetochore. Cell 135, 1039–1052. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishino T, Takeuchi K, Gascoigne KE, Suzuki A, Hori T, Oyama T, Morikawa K, Cheeseman IM, Fukagawa T. 2012. CENP-T-W-S-X forms a unique centromeric chromatin structure with a histone-like fold. Cell 148, 487–501. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.061) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poon SK, Peacock L, Gibson W, Gull K, Kelly S. 2012. A modular and optimized single marker system for generating Trypanosoma brucei cell lines expressing T7 RNA polymerase and the tetracycline repressor. Open Biol. 2, 110037 (doi:10.1098/rsob.110037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brun R, Schönenberger M. 1979. Cultivation and in vitro cloning or procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei in a semi-defined medium. Acta Trop. 36, 289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelly S, et al. 2007. Functional genomics in Trypanosoma brucei: a collection of vectors for the expression of tagged proteins from endogenous and ectopic gene loci. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 154, 103–109. (doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.03.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marchetti MA, Tschudi C, Kwon H, Wolin SL, Ullu E. 2000. Import of proteins into the trypanosome nucleus and their distribution at karyokinesis. J. Cell. Sci. 113, 899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woodward R, Gull K. 1990. Timing of nuclear and kinetoplast DNA replication and early morphological events in the cell cycle of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell. Sci. 95, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siegel TN, Hekstra DR, Cross GAM. 2008. Analysis of the Trypanosoma brucei cell cycle by quantitative DAPI imaging. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 160, 171–174. (doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.04.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. (doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. (doi:10.1093/molbev/mst010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. 2009. Jalview version 2: a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25, 1189–1191. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchan DWA, Minneci F, Nugent TCO, Bryson K, Jones DT. 2013. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED protein analysis workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W349–W357. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkt381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berriman M, et al. 2005. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 309, 416–422. (doi:10.1126/science.1112642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El-Sayed NM, et al. 2005. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science 309, 409–415. (doi:10.1126/science.1112631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ivens AC, et al. 2005. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science 309, 436–442. (doi:10.1126/science.1112680) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Logan-Klumpler FJ, et al. 2012. GeneDB—an annotation database for pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D98–D108. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson AP, et al. 2015. Kinetoplastid phylogenomics reveals the evolutionary innovations associated with the origins of parasitism. Curr. Biol. 26, 161–172. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.055) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. 2005. NCBI reference sequence (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D501–D504. (doi:10.1093/nar/gki025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. 2005. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D34–D38. (doi:10.1093/nar/gki063) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.