Abstract

Background

The present study sought to examine characteristics of suicidal ideation (SI) that predict a future suicide attempt (SA), beyond psychiatric diagnosis and previous SA history.

Methods

Participants were 506 adolescents (307 female) who completed the Columbia Suicide Screen (CSS) and selected modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC 2.3) as part of a 2-stage high-school screening and who were followed up 4-6 years later to assess for a SA since baseline. At baseline, participants who endorsed SI on the CSS responded to four questions regarding currency, frequency, seriousness, and duration of their SI. A subsample of 122 adolescents that endorsed SI at baseline also completed a detailed interview about their most recent SI.

Results

Thinking about suicide often (OR = 3.5, 95% CI = 1.7-7.2), seriously (OR = 3.1, 95% CI = 1.4-6.7), and for a long time (OR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.1-5.2) were associated with a future SA, adjusting for sex, the presence of a mood, anxiety, and substance use diagnosis, and baseline SA history. However, only SI frequency was significantly associated with higher odds of a future SA (OR = 3.6, 95% CI = 1.4-9.1) when also adjusting for currency, seriousness, and duration. Among ideators interviewed further about their most recent SI, ideating 1 hour or more (vs. less than 1 hour) was associated with a future SA (OR = 3.6, 95% CI = 1.0-12.7), adjusting for sex, depressive symptoms, previous SA history, and other baseline SI characteristics, and it was also associated with making a future SA earlier.

Conclusions

Assessments of SI in adolescents should take special care to inquire about frequency of their SI, along with length of their most recent SI.

Keywords: Suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, adolescence

Introduction

Suicidal ideation (SI) and suicide attempts (SAs) are more prevalent in adolescence than at any other time of life. Among 13-18-year-olds, lifetime prevalence of SI and attempts are approximately 12.1% and 4.1%, respectively, with rates of SAs 3 times higher among girls than boys (Nock et al., 2013). However, the rate of completed suicide among adolescents is low, at approximately 0.005% per year, with the rate among boys 3 times higher than girls (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). SA history, which predicts future suicidal behavior, has been a previous target of study (Goldston et al., 1999; Hulten et al., 2001; Lewinsohn, Rohde, and Seeley, 1994; Wichström, 2000). However, over half of suicides among adolescents are first-time attempts (Brent, Baugher, Bridge, Chen, and Chiappetta, 1999; Shaffer, Gould, et al., 1996), suggesting that only studying adolescents who have already made SAs misses a substantial proportion of adolescents at risk for suicide. Given its rarity in adolescence, predicting suicide death is a major challenge. However, we may obtain clues to specificity by investigating characteristics of SI that predict future attempts.

Retrospective assessments of adults and adolescents suggest that transitions from SI to attempts occur within a year of onset of SI (Kessler, Borges, and Walters, 1999; Nock, Hwang, Sampson, and Kessler, 2010; Nock et al., 2008, 2013), but how this transition occurs is unanswered. Typically-studied risk factors such as psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., major depression) are more strongly related to the presence of SI than they are to the transition from ideation to plans and attempts (Kessler et al., 1999; Nock et al., 2008, 2010). However, adolescent SI predicts future SAs (Reinherz, Tanner, Berger, Beardslee, and Fitzmaurice, 2006), even after adjusting for psychiatric diagnosis (Czyz and King, in press; Prinstein et al., 2008). Reinherz et al. found that adolescents who reported SI at age 15 had almost 12 times higher odds of having made a SA between ages 15 and 30, compared to adolescents who did not endorse SI at baseline, with no gender differences in this relation (Reinherz et al., 2006). Prinstein et al. found that the re-emergence of ideation 9-18 months after discharge from hospitalization predicted a SA during the same time period among adolescent inpatients (Prinstein et al., 2008). In a study of 376 adolescents who were followed up over 12 months following hospitalization for acute SI or an attempt, Czyz and King (in press) found that adolescents whose SI was consistently elevated over the course of the follow up had over 2 times higher odds of making a future SA relative to adolescents whose SI declined over the course of follow up. Careful study of SI characteristics may yield better information about which adolescents are at risk for making future SAs, beyond focusing on diagnosis or on adolescents who have already attempted suicide.

Studies of adolescent SI have focused on endorsement of any previous SI as predictive of a future SA (Lewinsohn et al., 1994l; Reinherz et al., 2006; Thompson, Kuruwita, and Foster, 2009; Wichström, 2000) or have examined changes in summary scores on a SI scale (Czyz and King, in press; Lewinsohn, Rohde, and Seeley, 1996; Prinstein et al., 2008), with the assumption that these scales accurately characterize the nature of SI but without empirical data to support which characteristics of ideation contribute to a future SA. The few studies that have focused on specific SI characteristics (e.g., planning, wish to die), have studied it in the context of an attempt (Miranda, De Jaegere, Restifo, and Shaffer, 2014; Negron, Piacentini, Graae, Davies, and Shaffer, 1997; Roberts, Roberts, and Chen, 1998). One cross-sectional study that compared 32 adolescents who presented to an emergency department with SAs to 35 adolescents who presented with SI found that attempters experienced longer duration of ideation but no difference in seriousness of their wish to die (Negron et al., 1997). A study of a community sample of 54 adolescent suicide attempters, ages 12-18, who were interviewed about their most recent SA found that planning an attempt for one hour or longer (vs. less than an hour) and having a serious wish to die at the time of the attempt were associated with over 5 times higher odds of making a repeat SA within a 4-6-year follow-up period (Miranda et al., 2014). We know of no prospective study in adolescents that characterized the nature of SI among adolescents who went on to make attempts, a gap in knowledge that the present study sought to address.

We examined the characteristics of SI that would prospectively be associated with risk for a future SA. First, we examined whether different forms of inquiry on a screen for SI would differentially predict risk for a SA over a 4-6-year follow-up period among 506 high school students. Next, we examined whether there would be specific features of SI that would best predict a future attempt among a subsample of 122 adolescents who endorsed SI and who were interviewed in further detail, at baseline, about their most recent SI.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 506 adolescents, ages 12-21 (M = 15.6, SD = 1.4), who took part in a two-stage screening of 7 high schools in the New York City metropolitan area (see Shaffer et al., 2004, for a summary of recruitment and consent procedures for the screening) and who also provided data as part of a 4-6-year follow-up study. The schools were chosen to represent different types of schools in the New York City metropolitan area and consisted of 6 urban and 1 suburban school (including 2 single-sex parochial schools and 1 vocational school). Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. At baseline, 1729 high school students completed the Columbia Suicide Screen (CSS), with a reported SI prevalence (past 3 months) of 11% and lifetime SA prevalence of 6% among respondents (Shaffer et al., 2004). Six hundred forty-one of these individuals, oversampled for a history of SI or SA, were selected to complete the mood, anxiety, and substance use modules of the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC), version 2.3 (Shaffer, Fisher, et al., 1996). Details about selection procedures can be found elsewhere (Shaffer et al., 2004). Participants who endorsed SI during any stage of the screening were also eligible to be interviewed about their most recent SI via the SI module of the Adolescent Suicide Interview (ASI-SI; see below).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Adolescents who Took Part in the Follow up

| All (N = 506) M (SD) | No SA at Follow Up (N = 464) M (SD) | SA at Follow Up (N = 42) M (SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Baseline) | 15.6 (1.4) | 15.6 (1.4) | 15.6 (1.4) | 0.15 | .88 |

| BDI Score (Baseline) | 10.9 (8.9) | 10.5 (8.7) | 16.4 (9.9) | 3.95 | .00 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 307 (61) | 276 (59) | 31 (74) | 3.31 | .07 |

| Male | 199 (39) | 188 (41) | 11 (26) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 219 (44) | 207 (46) | 12 (29) | 5.16 | .27 |

| Black | 126 (25) | 113 (25) | 13 (31) | ||

| Hispanic | 88 (18) | 77 (17) | 11 (26) | ||

| Asian | 35 (7) | 32 (7) | 3 (7) | ||

| Other | 27 (5) | 24 (5) | 3 (7) | ||

| C-DISC Diagnosis at Baseline | |||||

| Mood (past 6 months) | 66 (13) | 53 (11) | 13 (31) | 12.95 | .00 |

| Anxiety (past 6 months) | 71 (14) | 60 (13) | 11 (26) | 5.61 | .02 |

| Substance Use (past 6 months) | 27 (5) | 22 (5) | 5 (12) | 3.91 | .05 |

| Suicidal Ideation, past 3 months (CSS) | |||||

| Thought about killing yourself? | 149 (29) | 123 (27) | 26 (62) | 23.23 | .00 |

| Still thinking about killing yourself? | 43 (8) | 37 (8) | 6 (14) | 1.97 | .16 |

| Often thought about killing yourself | 105 (21) | 82 (18) | 23 (55) | 32.22 | .00 |

| Thought seriously about killing yourself? | 76 (15) | 57 (12) | 19 (45) | 32.77 | .00 |

| Thought about killing yourself for a long time? | 65 (13) | 50 (11) | 15 (36) | 21.39 | .00 |

| Suicide Attempt History at Baselinea (CSS, C-DISC, or ASI) | 86 (17) | 65 (14) | 21 (50) | 35.36 | .00 |

Includes 11 adolescents who reported no suicide attempt history at baseline but who reported, at follow up, having made a lifetime attempt that occurred prior to the baseline assessment, and whose reported age of their most recent attempt fell before or at their age at baseline.

Diagnoses assessed at Baseline: Mood = Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Dysthymic Disorder; Anxiety = Panic Disorder (PD), Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), or Overanxious Disorder; Substance use = Alcohol Abuse/Dependence, Marijuana Abuse/Dependence, or Other Substance Use/Dependence.

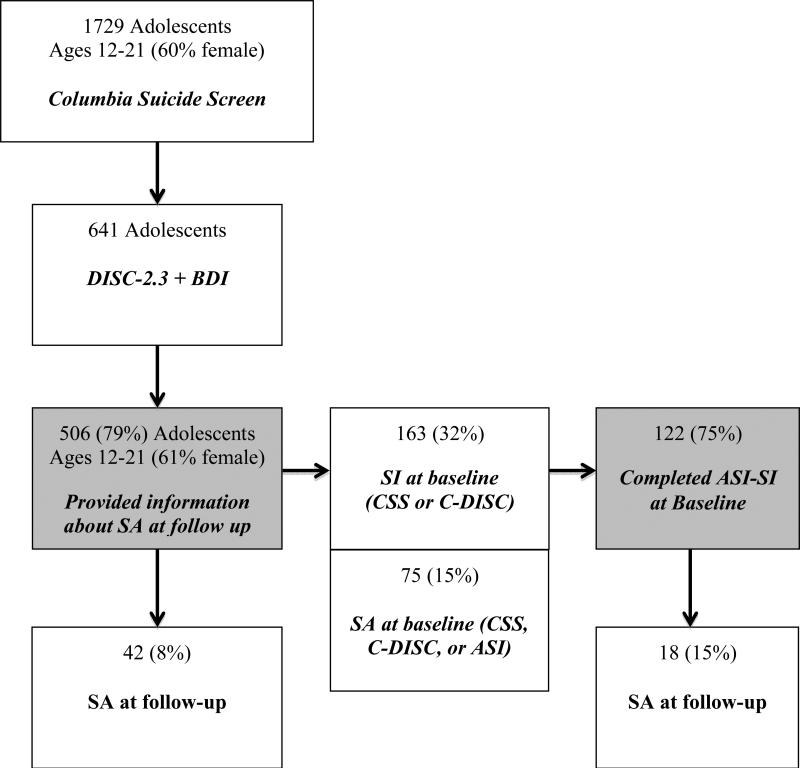

Adolescents were contacted by telephone 4-6 years later (M = 5.1, SD = 1.0) and, after providing informed consent (or parental consent with child assent for minors), took part in an interview in which they were asked whether they had made a SA since the baseline interview. Five hundred six (79%) individuals from the larger sample of 641 adolescents provided this information (Forty-six additional adolescents took part in the follow-up study but did not provide information about their SAs). Of these 506 adolescents, 163 individuals had reported SI at baseline – 149 on the CSS (assessed for the previous 3 months) and an additional 14 on the C-DISC (assessed for the previous 6 months), and 122 of these 163 adolescents had also completed the ASI-SI at baseline. Final sample selection is depicted in Figure 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, race/ethnicity, and diagnosis among participants who did and did not take part in the follow up.

Figure 1.

Sample selection. Shaded boxes indicate the final samples included in the analyses.

Materials and consent procedures for the baseline study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, the New York City Board of Education, and the Archdiocese of New York, and the follow-up study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Measures

Columbia Suicide Screen (Shaffer et al., 2004)

Two suicide-related questions (with “yes” versus “no” response choices) were embedded within a larger, 32-question health survey. The questions were: 1) “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” and 2) “During the past three months, have you thought about killing yourself?” Test-retest reliabilities (ĸ) for these questions were .48 and .58, respectively (Shaffer et al., 2004). Participants who endorsed SI were asked four additional yes/no questions: 1) “Are you still thinking about killing yourself?” (currency); 2) “Have you often thought about killing yourself?” (frequency); 3) “Have you thought seriously about killing yourself?” (seriousness); and 4) “Have you thought about killing yourself for a long time?” (duration). Associations in responses to these 4 questions ranged from V = .40 to .63 in the present sample.

Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, et al., 1996)

At baseline, the C-DISC, version 2.3, was administered via computer by lay interviewers to establish psychiatric diagnoses consistent with DSM-III-R criteria (Shaffer, Fisher, et al., 1996). Diagnoses assessed are listed in Table 1.

Adolescent Suicide Interview for Suicidal Ideation (ASI-SI)

The ASI-SI is a semi-structured interview to assess the characteristics of adolescents’ SI. It was developed to complement the ASI for adolescent suicide attempters (Miranda et al., 2008; Shaffer, Gould, Fisher, and Trautman, 1990), which was also administered as part of the study and inquired about lifetime SA history. Questions are presented in a fixed order, with suggested probes, and fixed interviewer-completed rating scales that focus on the characteristics of the individual's most recent SI episode, including timing of their most recent ideation, frequency of SI, wish to die during their most recent SI, and length of a typical episode of ideation. Questions for which participants did not know an answer were counted as missing data. The ASI-SI was administered by Bachelor's-level research assistants, supervised by a psychiatrist.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck and Steer, 1993)

The BDI contains 21 items that assess cognitive, behavioral, affective, and somatic components of depression. It has demonstrated good reliability and validity for use with adolescents (Strober, Green, and Carlson, 1981; Roberts, Lewinsohn, and Seeley, 1991; Teri, 1982). The SI question was omitted from total-score calculations. Cronbach's alpha for the BDI was .88 in the present study.

Suicide Attempt at Follow up

SAs during follow-up were determined via a modified version of the ASI, which asked participants the question, “In your whole life, have you ever tried to kill yourself?”, number of attempts, age at their last attempt, and whether their most recent attempt occurred after the baseline interview. Individuals who reported that any SA occurred after baseline were classified as having made a SA during the follow-up period (Miranda et al., 2014). Time between baseline and the SA was determined by subtracting participant age at baseline from age at their most recent follow-up attempt. Note that agreement between SA history, as reported on either the ASI or CSS at baseline, and SA history at follow up was substantial, with ĸ = .69 and .70, respectively (excluding adolescents who reported a first-time SA at follow up that occurred after the baseline interview).

Data Analysis

To examine whether each of the baseline CSS ideation questions would predict a future SA (reported at follow-up) among the larger sample of 506 adolescents who provided this information at follow up, separate logistic regression analyses were conducted in which currency, frequency, seriousness, and duration of SI on the CSS were entered as predictors of a future SA, adjusting for gender, presence of a C-DISC mood, anxiety, and substance use diagnosis, and SA history (as reported on the CSS, C-DISC, or ASI at baseline), with covariates included in the model if they differentiated between adolescents who did vs. did not make a SA at follow up at an alpha level of p < .10. In addition, all four CSS questions were entered simultaneously into one multivariate analysis to examine whether they predicted a future SA, adjusting for the other covariates.

Data from the 122 participants who completed the ASI-SI and the follow up were also analyzed via logistic regression. SI characteristics examined as predictors of a future SA included timing of the most recent SI, frequency of SI, seriousness of the adolescent's wish to die, and length of the most recent SI episode, with variables dichotomized in a manner consistent with previous research (Miranda et al., 2014). Each characteristic was entered into its own logistic regression, adjusting for gender, depressive symptoms, and SA history, and also into a full model that included all characteristics. This model adjusted for depressive symptoms, rather than diagnosis, in order to reduce the number of variables in the model, given the smaller sample size.

Results

Baseline Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt History

At baseline, 149 (29%) out of 506 participants reported recent (previous 3 months) SI on the CSS, and 75 (15%) participants reported a lifetime SA history: 61 on the CSS, 65 on the C-DISC, and 63 on the ASI. There were 11 additional adolescents who did not report a SA at baseline but who reported a SA at follow up that they said occurred prior to baseline, and this information was verified by comparing their age at baseline to the age when they reported having made their most recent SA at follow up. These adolescents were thus also classified as having a lifetime SA history at baseline, for a total of 86 (17%) adolescents with a lifetime SA history at baseline. Forty-three (8%) participants reported that they were still thinking about suicide (currency), 105 (21%) reported that they had often thought about killing themselves (frequency), 76 (15%) reported that they had thought seriously about killing themselves (seriousness), and 65 (13%) reported that they had thought about killing themselves for a long time (duration).

Forms of Suicidal Ideation at Baseline that Predicted a Suicide Attempt 4-6 Years Later

No suicide deaths occurred during the study period. Forty-two (8%) out of 506 adolescents endorsed having made a SA during the follow-up period, either through ingestion (N = 23; 55%), use of a cutting instrument (N = 7; 17%), a gun (N = 5; 12%), or other methods (N = 7; 17%). Endorsement of recent SI (vs. not) in the previous 3 months at baseline was associated with 2.6 times higher odds of a future SA (95% C.I. = 1.3-5.5; p < .01), adjusting for sex, diagnosis, and previous SA history. Frequency and seriousness of ideation were associated with about 3 times higher odds of reporting a future SA (p < .05) in separate regression analyses that adjusted for sex, diagnosis, and SA history (see Table 2). In a multivariate model that included all forms of SI as predictors of a future SA, only frequency of SI was associated with increased risk of a future SA (OR = 3.6, 95% C.I. = 1.4-9.1; p < .01, while currency (OR = 0.2, 95% C.I. = 0.1-0.8; p < .05) was associated with decreased risk of a future SA.

Table 2.

Responses to CSS Suicidal Ideation Questions at Baseline as Predictors of a Suicide Attempt at Follow-up (N = 506)

| Columbia Suicide Screen Ideation Questions | OR (95% CI), Separate Regressionsa | OR (95% CI), Full Model |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ... | 1.3 (0.6-2.9) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Mood | ... | 1.6 (0.7-4.0) |

| Anxiety | ... | 1.2 (0.5-3.2) |

| Substance | ... | 1.2 (0.3-4.0) |

| Suicide Attempt History | ... | 3.8** (1.7-8.3) |

| Are you still thinking about killing yourself? | 0.6 (0.2-1.9) | 0.2* (0.1-0.8) |

| Have you often thought about killing yourself? | 3.5** (1.7-7.2) | 3.6** (1.4-9.1) |

| Have you thought seriously about killing yourself? | 3.1** (1.4-6.7) | 2.5+ (0.9-6.5) |

| Have you thought about killing yourself for a long time? | 2.3* (1.1-5.2) | 0.8 (0.3-2.2) |

Each suicidal ideation characteristic entered into its own logistic regression, adjusting for sex, diagnosis, and suicide attempt history

Indicates different values for each regression.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Characteristics of Suicidal Ideation among Adolescent Ideators Interviewed at Baseline

Among the 122 participants who completed the ASI-SI at baseline and took part in the follow-up (see Table 3), 21% percent of adolescents (N = 25 out of 119 who provided responses) reported that their most recent SI occurred within the previous 2 weeks, while the majority of adolescents (79%; N = 94) reported their SI occurred more than 2 weeks before inquiry. Fifty-three percent (N = 54 out of 101 who provided responses) of adolescents reported an ideation frequency of more than once per week. Most adolescents reported that they did not want to die or were uncertain about wanting to die during their most recent ideation episode (N = 93 out of 121 who provided responses; 77%), with 23% (N = 28) reporting they wanted to die. Seventy-two percent of adolescents reported that the typical length of their most recent SI was less than 1 hour (N = 85 out of 118 who provided responses), while 28% (N = 33) reported SI that lasted an hour or longer.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of ASI-SI Completers who took Part in the Follow Up

| All (N = 122) M (SD) |

All

|

t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SA during Follow Up (N =104) M (SD) | SA during Follow Up (N = 18) M (SD) | ||||

| Age (Baseline) | 15.5 (1.3) | 15.5 (1.3) | 15.4 (1.4) | 0.06 | .95 |

| BDI Score (Baseline) | 16.6 (9.8) | 15.9 (9.8) | 20.3 (9.0) | 1.78 | .08 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 73 (60) | 62 (60) | 11 (61) | 0.01 | .90 |

| Male | 49 (40) | 42 (40) | 7 (39) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 66 (54) | 56 (54) | 10 (56) | 4.73 | .32 |

| Black | 18 (15) | 17 (16) | 1 (6) | ||

| Hispanic | 18 (15) | 16 (15) | 2 (11) | ||

| Asian | 12 (10) | 10 (10) | 2 (11) | ||

| Other | 8 (7) | 5 (5) | 3 (17) | ||

| DISC Diagnosis at Baseline | |||||

| Mood Diagnosis | 30 (25) | 24 (24) | 6 (33) | 0.87 | .35 |

| Anxiety Diagnosis | 30 (25) | 23 (22) | 7 (39) | 2.33 | .13 |

| Substance Use Diagnosis | 16 (13) | 11 (11) | 5 (28) | 3.99 | .05 |

| Suicide Attempt History at Baseline (CSS, C-DISC, or ASI) | 25 (20) | 19 (18) | 6 (33) | 2.14 | .14 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of Most Recent SI (ASI-SI) | |||||

| Timing (N = 119) | |||||

| > 2 weeks ago | 94 (79) | 80 (79) | 14 (78) | 0.02 | .89 |

| Within past 2 weeks | 25 (21) | 21 (21) | 4 (22) | ||

| Frequency (N = 101) | |||||

| > 1 every 2 weeks | 47 (47) | 42 (49) | 5 (31) | 1.79 | .18 |

| > 1 per week | 54 (53) | 43 (51) | 11 (69) | ||

| Wish to die (N = 121) | |||||

| Did not want to die/uncertain | 93 (77) | 82 (80) | 11 (61) | 2.95 | .09 |

| Wanted to die | 28 (23) | 21 (20) | 7 (39) | ||

| Length of typical single ideation (N = 118) | |||||

| < 1 hour | 85 (72) | 77 (76) | 8 (47) | 6.15 | .01 |

| 1 hour or more | 33 (28) | 24 (24) | 9 (53) |

Characteristics of Suicidal Ideation that Predict a Future Suicide Attempt among Ideators with or without a Lifetime Suicide Attempt History

Of the 122 suicide ideators who completed the follow-up assessment 4-6 years later, 15% (N = 18) of adolescents made a SA during the follow-up period (11 through ingestion, 3 with a gun, 2 through cutting, 1 through attempted hanging, and 1 through a combination of ingestion and cutting). There were no significant differences by age, gender, or race/ethnicity among individuals who did or did not endorse a SA at follow up.

Of the four specific characteristics of SI examined as predictors of a future SA (see Table 4), SI length greater than 1 hour (vs. less than 1 hour) (OR = 3.6, p < .05) was associated with a future SA. Frequency of SI, wish to die, and timing of SI were not significantly associated a future SA.

Table 4.

Logistic Regressions Predicting Suicide Attempt (SA) at Follow-up (N = 122)

| ORa (95% CI) Separate Regressions | p | OR (95% CI) Full Model | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ... | 1.0 (0.4-3.7) | .98 | |

| BDI | ... | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | .30 | |

| Suicide Attempt History | ... | 1.4 (0.3-5.5) | .65 | |

| Timing of most recent SI (N = 119) | ||||

| > 2 weeks ago+ | ||||

| Within past 2 weeks | 0.6 (0.2-2.5) | .53 | 0.7 (0.1-3.3) | .65 |

| Frequency of ideation, most recent episode (N = 101) | ||||

| > 1 every 2 weeks+ | ||||

| > 1 per week | 1.8 (0.6-5.8) | .32 | 1.3 (0.4-4.7) | .67 |

| Wish to die, most recent episode (N = 121) | ||||

| Did not want to die/uncertain+ | ||||

| Wanted to die | 2.2 (0.7-6.7) | .15 | 1.2 (0.3-4.8) | .82 |

| Length typical single ideation, last episode (N = 118) | ||||

| < 1 hour+ | ||||

| 1 hour or more | 3.1 (1.0-9.3) | .04 | 3.6 (1.0-12.7) | .04 |

Analyses adjust for sex, suicide attempt history, and BDI score at baseline.

Reference category

Indicates different values for each regression.

Of the 18 adolescents who made an attempt within the follow-up period, 11 made one SA – 5 within a year from baseline, 3 within two years of baseline, and 2 adolescents 3-4 years later (the interval for 1 participant was unknown). Seven adolescents made 2 SAs, with the most recent attempt occurring 1-5 years (M = 2.4, SD = 1.4) from baseline (information was not available about approximate timing of their first attempt). Among the adolescents who made one SA, those with a baseline SI length of one hour or more (n = 5) made a future SA, on average, within less than one year (M = 0.6, SD = 0.9), compared to individuals with typical SI of less than one hour (n = 5), whose future SA occurred within about 2 years of their baseline interview (M = 2.4, SD = 1.1), t(8) = 2.78, p < .05. This difference was even larger when examining adolescents (N = 8) that endorsed SI without a SA history at baseline. Among these adolescents, those whose baseline SI lasted one hour or more made the transition to a future SA, on average, within less than one year (M = 0.5, SD = 1.0), compared to individuals with typical SI of less than one hour, whose SA occurred within about 3 years (M = 2.8, SD = 1.0), t(6) = 3.25, p < .05.

Discussion

The present study is the first, of which we are aware, to prospectively identify specific characteristics of SI that predict a future SA among adolescents, independently of psychiatric diagnosis and previous SA history. Endorsement of recent SI (past 3 months) on a screening questionnaire at baseline, along with frequency (“Have you often thought...?”), seriousness (“Have you thought seriously...?”), and duration of ideation, were associated with increased risk of making a SA during a follow-up period. Among a subsample of adolescents who were interviewed about their SI, length of ideation (1 hour or more) significantly predicted a future attempt. Finally, preliminary evidence suggested that adolescents whose ideation lasted one hour or more made their attempt, on average, within one year of their baseline interview.

Our results support previous findings that endorsing recent SI at one time point is associated with future SAs (Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Reinherz, 2006; Thompson et al., 2009; Wichström, 2000). However, not all SI characteristics seem to predict a future SA equally. These data are also consistent with Negron et al.'s (1997) finding that adolescent attempters reported greater length of SI during their suicidal episode, compared to ideators, and also with Miranda et al.'s (2014) findings that adolescent attempters who reported longer suicide planning (1 hour or more) leading up to their most recent SA were at greater risk for a future attempt, compared to adolescents whose attempts were more impulsive. Interestingly, these findings are in contrast to a recent retrospective study with adults that found that among individuals whose first onset of SI was at about age 26, recurrence of SI was associated with lower odds of a SA (ten Have, van Dorsselaer, & de Graaf, 2013). However, this study did not measure length of SI. Perhaps among individuals who have not thought about suicide by adulthood, persistence of SI may be protective against SA. However, when SI occurs as early as adolescence, it enhances risk of a SA (Thompson et al., 2012). Alternatively, a 10-year follow-up study of a nationally representative sample of 15-54-year-olds found that a baseline history of SI without a plan was associated with decreased risk for a future suicidal plan, but having a history of making a previous suicide plan increased the odds of making future suicidal plans (Borges et al., 2008). Thus, it may not merely be the presence of SI, but the seriousness of SI that enhances risk for future suicidal behavior.

These findings might be understood in light of prevailing theories of suicide. Rudd's Fluid Vulnerability Theory suggests that individuals can establish a vulnerability to future SAs through experience (Rudd, 2006), as with having a history of previous SAs or SI. People who are more chronically vulnerable to suicidal behavior need fewer triggers to set off a suicidal episode (Rudd, 2006). Previous SAs may lower this threshold (Joiner and Rudd, 2000), as may length of suicide planning (Bagge, Glenn, and Lee, 2013). Our data support the possibility that longer duration of SI contributes to establishing vulnerability to SAs. The present findings might also be interpreted through Joiner's interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide, which suggests that suicide risk is a function of how much individuals have acquired the capability to enact lethal self-injury, combined with how seriously they want to die (Joiner, 2005). Greater length of ideation may serve as a form of practice for future suicidal behavior, contributing to this acquired ability.

One unexpected finding was that currency of ideation (i.e., whether adolescents endorsed that they were still thinking about killing themselves) was associated with lower odds of a future SA in a full model that included all variables. This finding should be interpreted with caution, however, because endorsement of current SI was only associated with lower odds of a future SA after adjusting for the other ideation characteristics, suggesting that the findings may be due to the correlations among the questions (i.e., the correlations between currency of ideation and frequency, seriousness, and duration of SI were .47, .51, and .39, respectively).

Implications for Assessment and Treatment

This study suggests that screenings for adolescent suicide risk should not only inquire about SI, but also about how seriously, how often, and for how long adolescents have thought about suicide. Further, adolescents with recent SI may be at risk of transitioning to an attempt to the degree that they ideate for a long time (i.e., 1 hour or more). Assessments should thus inquire about these specific ideation characteristics. These characteristics may also serve as targets for intervention. For instance, treatment of adolescents who present with SI should focus on techniques that may decrease the length of their ideation (e.g., addressing distress tolerance, problem-solving, and mindfulness). Furthermore, interventions might also incorporate suicide safety plans (see Stanley & Brown, 2012) for adolescents who report greater frequency or length of their SI and even distress safety plans for undisclosed current suicide premeditation (Bagge, Littlefield, & Lee, 2013).

At the same time, the wording of the inquiry is important. Endorsement of a question about SI duration on the CSS (i.e., “Have you thought about killing yourself for a long time?”) was a less robust predictor of a future SA than was the actual length of adolescents’ most recent SI. Thus, inquiries about SI duration should be specific and focus on length.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include a racially and ethnically diverse community sample that was followed up over time, assessment of multiple characteristics of SI, adjustment for psychiatric diagnosis, and a high rate of follow-up (75-79%). However, there are a number of limitations. First, our assessment of SI characteristics was retrospective and thus subject to recall bias. Second, our assessment of a SA at follow-up was based on response to two questions on a telephone interview (i.e., whether participants had ever made a SA and whether it had been made since the baseline interview). Third, timing of the most recent attempt was determined by the difference between the participants’ age at baseline and the age they reported being when they made their most recent attempt during the follow-up period. Thus, it was only precise down to years. Fourth, despite the fact that the present study inquired about such characteristics as “seriousness” and length of SI, it did not inquire about specific features of suicide planning, such as whether adolescents considered how, when, and where they would make an attempt. While it might be inferred that adolescents who reported a greater length of ideation were more likely to have a detailed plan, future research should specifically inquire about these characteristics. Finally, seven of the 18 adolescents who reported an attempt at follow-up made more than one attempt, and we thus did not have information on timing of their first attempt.

Concluding Comments

This is the first study of which we are aware to examine whether the specific characteristics of SI assessed by questions used to screen for SI predict whether adolescents will make a future SA, beyond diagnosis and history of a previous SA. It is also the first study of which we are aware to examine specific SI characteristics associated with a future attempt among adolescents who were interviewed about their SI. In addition to making inquiries about whether a teenager has experienced recent SI, these data suggest that screening for SI should inquire about whether adolescents have often and seriously thought about killing themselves. Further, length of a typical ideation episode is informative about their likelihood of transitioning to a future SA and also the timing of that transition. Thus, clinicians should also inquire about length of adolescents’ recent SI, as an ideation episode lasting an hour or more may substantially increase their risk of making an attempt.

Key points.

Little research to date has addressed which characteristics of suicidal ideation contribute to the transition to future suicide attempts among adolescents.

We found that among adolescents screened for suicidal ideation, thinking about suicide often was associated with over three times higher odds of making a future suicide attempt, adjusting for diagnosis, previous attempt history, and responses to other suicidal ideation questions.

Adolescents whose baseline suicidal ideation lasted 1 hour or longer had 3.6 times higher odds of making a future suicide attempt and made the transition to a future attempt earlier than did adolescents whose baseline ideation lasted less than 1 hour.

Assessments of suicidal ideation should inquire about the form that suicidal ideation takes, including its frequency and duration.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant R49/CCR 202598 from the Centers for Disease Control, NIMH grants P30 MH 43878 and ST32MH-16434, and grants from the American Mental Health Foundation and the Carmel Hill Foundation, to D.S.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Bagge CL, Glenn CR, Lee H-J. Quantifying the impact of recent negative life events on suicide attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:359–368. doi: 10.1037/a0030371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Littlefield AK, Lee H-J. Correlates of proximal premeditation among recently hospitalized suicide attempters. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;150:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, Ruscio AM, Kessler RC. Risk factors for the incidence and persistence of suicide-related outcomes: A 10-year follow-up study using the National Comorbidity Surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;105:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, Chen T, Chiappetta L. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1497–1505. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [June 14, 2013];Suicide injury deaths and rates per 100,000, 2010, United States. 2013 Available from URL: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal_injury_reports.html.

- Czyz EK, King CA. Longitudinal trajectories of suicidal ideation and subsequent suicide attempts among adolescent inpatients. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.836454. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Reboussin DM, Reboussin BA, Frazier PH, Kelley AE. Suicide attempts among formerly hospitalized adolescents: a prospective naturalistic study of risk during the first 5 years after discharge. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:660–671. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultén A, Jiang G-X, Wasserman D, Hawton K, Hjelmeland H, De Leo D, Ostamo A, Salander-Renberg E, Schmidtke A. Repetition of attempted suicide among teenagers in Europe: Frequency, timing, and risk factors. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;10:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s007870170022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Rudd MD. Intensity and duration of suicidal crisis vary as a function of previous suicide attempts and negative life events. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:909–916. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:297–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: Prevalence, risk factors and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, De Jaegere E, Restifo K, Shaffer D. Longitudinal follow-up study of adolescents who report a suicide attempt: Aspects of suicidal behavior that increase risk of a future attempt. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:19–26. doi: 10.1002/da.22194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Scott M, Hicks R, Wilcox HC, Harris Munfakh JL, Shaffer D. Suicide attempt characteristics, diagnoses, and future attempts: Comparing multiple attempters to single attempters and ideators. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:32–40. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negron R, Piacentini J, Graae F, Davies M, Shaffer D. Microanalysis of adolescent suicide attempters and ideators during the acute suicidal episode. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1512–1519. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66559-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, Gluzman S, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam E, Kessler RC, Lepine JP, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Williams D. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity, and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15:868–876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Simon V, Aikins JW, Cheah CSL, Spirito A. Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:92–103. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Tanner JL, Berger SR, Beardslee WR, Fitzmaurice GM. Adolescent suicidal ideation as predictive of psychopathology, suicidal behavior, and compromised functioning at age 30. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1226–1232. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Screening for adolescent depression: A comparison of depression scales. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:58–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen R. Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1294–1300. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd DM. Fluid vulnerability theory: A cognitive approach to understanding the process of acute and chronic suicide risk. In: Ellis TE, editor. Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy. Vol. 2006. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Bourdon K, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study (Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould M, Fisher P, Trautman P. Adolescent Suicide Interview. 1990 Unpublished interview. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Scott M, Wilcox H, Maslow C, Hicks R, Lucas CP, Garfinkel R, Greenwald S. The Columbia Suicide Screen: validity and reliability of a screen for youth suicide and depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety Planning Intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19:256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Green J, Carlson G. Utility of the Beck Depression Inventory with psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:482–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AH, Dewa CS, Phare S. The suicidal process: age of onset and severity of suicidal behavior. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47:1263–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Kuruwita C, Foster EM. Transitions in suicide risk in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L. The use of the Beck Depression Inventory with adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1982;10:277–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00915946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S, de Graaf R. Prevalence and risk factors for first-onset of suicidal behaviors on the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichström L. Predictors of adolescent suicide attempts: A nationally representative longitudinal study of Norwegian adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:603–610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]