Abstract

Objectives

The authors examined whether low-income mothers, who have a regular source of dental care (RSDC), rate the dental health of their young children higher than mothers without a RSDC.

Methods

From a population of 108,151 children enrolled in Medicaid aged 3 to 6 and their low-income mothers in Washington state, a disproportionate stratified random sample of 11,305 children aged 3 to 6 was selected from enrollment records in four racial/ethnic groups: 3,791 Black; 2,806 Hispanic 1,902 White; and 2,806 other racial/ethnic groups. A mixed-mode survey was conducted to measure mother RSDC and mother ratings of child’s dental health and pain. The unadjusted response rate was 44%, yielding the following eligible mothers: 816 Black, 1,309 Hispanic, 1,379 White, 237 Asian, and 133 American Indian. Separate regression models for Black, Hispanic and White mothers estimated associations between the mothers having a RSDC and ratings of child dental health.

Results

Across racial/ethnic groups, mothers with a RSDC consistently rated their children’s dental health 0.15 higher on a 1-to-5 scale (where 1 means ‘poor’ and 5 means ‘excellent’) than mothers without a RSDC, controlling for child and mother characteristics and the mothers’ propensity to have a RSDC. This difference can be interpreted as a net movement of one level up the scale by 15% of the population.

Conclusions

Across racial/ethnic groups, low-income mothers who have a regular source of dental care rate the dental health of their young children higher than mothers without a RSDC.

Keywords: Children, mothers, oral health, regular source of dental care, Medicaid

Tooth decay is a growing, severe problem among low-income and minority preschool children that is compounded by limited access to dental care (1–4). Simply increasing children’s access to dental care through universal dental insurance may not reduce the inequalities in oral health (5). An additional approach to solving this public health problem may exist through the connection between mother and child oral health and the mother’s access to dental care (6). Mothers are the primary source of the dental caries bacteria infection in their children. Caries-preventive technologies delivered to mothers effectively reduce their cariogenic bacteria and the caries experiences of their infants (6–18). Through regular dental care, mothers build positive dental knowledge, attitudes and self-care practices, (19, 20) which may increase the child’s dental utilization and oral health (21, 22). If low-income mothers have a regular source of dental care (RSDC) and receive preventive services, oral health benefits may accrue to both mother and child through biological and dental care mechanisms.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined whether young children of mothers with a RSDC have better oral health than children of mothers without a RSDC, particularly in a racial/ethnically diverse and low-income population. In a Washington state study of low-income children, having a mother with a RSDC at baseline was associated with greater odds of receiving any dental care in the following year (odds ratios 1.69 and 1.84 for young children of Black or Hispanic mothers, respectively; for White mothers the relationship was positive but not significant) (23). This suggests that child dental utilization is one of potentially several mechanisms linking mother RSDC to a child’s oral health.

In a population-based sample of young children in low-income families with Medicaid dental insurance in Washington state, we examine, by racial/ethnic group, whether mothers, who have a regular source of dental care (RSDC), rate the dental health of their young children higher than mothers without a RSDC. Caregiver reports of the child oral health are correlated highly with clinical findings. In a national sample of children aged 2–5, 11 percent of parents rated their children’s oral health as fair or poor (versus good, very good, excellent), and of all the parents, those in low-income and minority families gave lower ratings of their children’s oral health (24). Parents’ ratings of their children’s oral health were correlated strongly with the number of children’s carious tooth surfaces. In a representative sample of 885 low-income African American families with children aged 1–5 in Detroit, caregivers’ perceptions of their children’s oral health were significantly associated with children’s dental caries and perceived limitations of oral functions/activities (25).

METHODS

POPULATION, SAMPLE AND STUDY DESIGN

The population consisted of 108,151 children enrolled in Medicaid (the U.S. public dental insurance program for low-income persons) aged 3 to 6 and their mothers in Washington state (children’s household income eligibility for Medicaid in Washington state is 250% of Federal poverty level). We chose children aged 3–6 because the study’s main objective was estimating whether mother RSDC was related to child dental utilization, and dental utilization for children below age 3 was less than 30%, which would have decreased the likelihood of detecting an association between mothers’ RSDC and their children’s dental utilization (26).

In April 2004, a disproportionate stratified random sample of 11,305 preschool children aged 3 to 6 was selected from Medicaid enrollment records in the following four racial/ethnic groups: 3,791 Black; 2,806 Hispanic; 1,902 White; and 2,806 other racial/ethnic groups. If a household had more than one child in the age range, one child was selected randomly. The cross-sectional study design consisted of a survey of children’s mothers in September – December 2004. Study protocols were approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board.

MEASURES

Measures were derived from Hay et al’s conceptual model of oral health and Grembowski et al’s conceptual model of dental care (19, 27).

Mother Rating of Child Oral Health

Mothers rated the dental health of their children on a 5-point scale of poor (1), fair, good, very good, excellent (5). Mothers also reported whether their children sometimes or frequently had any pain in his or her teeth versus no pain.

Mother Regular Source of Dental Care

RSDC was measured by whether a mother had a regular place of dental care or regular dentist based on Starfield’s (28) definition of a regular source of care: one place, one provider, over time for preventive and therapeutic care. Measures satisfying Starfield’s criteria were constructed from usual source of health care items in previous medical and dental surveys (29–31).

A mother had a regular place of dental care if she: a) responded ‘yes’ to “Is there a particular dental office, clinic, health center or other place that you usually go to for dental care?;” and b) the place where the mother goes was not a hospital emergency room; and c) she went to the place for 1 year or more; and d) the place was a source of preventive services, measured by having teeth cleaned in the past 2 years (32). Mothers had a regular dentist if: a) items (a), (b) and (d) for a regular dental place were met; and b) mothers reported seeing the same dentist each time they went there; and c) mothers went to that dentist for 1 year or more.

Mother, Family and Place Characteristics

Mothers’ race/ethnicity was measured by the question: “What race or ethnic background best describes you?,” with responses of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish; White, not Hispanic; Black or African American; American Indian; Alaska Native; Asian (such as Vietnamese, Korean, Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, Asian Indian); Pacific Islander (such as Hawaiian or Samoan); or some other race/ethnicity. Socioeconomic status was measured by the mother’s highest educational degree, employment status, and family income in 2003 (categorized by less than $10,000, between $10,000 – $20,000, and over $20,000). Dental insurance was measured by whether the mother had no dental insurance, Medicaid, or private dental insurance from an employer. Mother characteristics also included mother’s age, single parent, race/ethnicity, current cigarette smoker, which mode of the survey the mother completed, dental fear, and belief that regular dentist visits can prevent loose teeth (33). Mothers rated their dental health on a 5-point scale of poor (1), fair, good, very good, excellent (5). Mental health symptoms in the past 4 weeks were assessed by averaging the mother’s responses to a 6-item mental health scale, where each item’s score ranged from 1 (best) to 6 (worst) (34, 35). Mothers reported whether they were born in the U.S.

Child Characteristics

Child survey measures included gender, age, whether the child had dental insurance other than Medicaid, and mother’s rating of the child’s dental fear (33).

The following child measures were collected from Medicaid records to compare children with and without completed questionnaires: whether the child had any Medicaid dental claims in January – April 2004 before the sample was drawn, gender, age, number of family members, whether the child was disabled, member of an American Indian tribe, immigrated, English was family’s primary language, and whether the child was enrolled in ABCD, a program to increase access to dental care for Medicaid preschool children in Washington state (30).

DATA COLLECTION

In June 2004 the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS), which administers the Medicaid Program, mailed the parents of sampled children letters describing the study and containing instructions to notify DSHS if they did not want to participate. Three hundred ninety-six parents opted out of the study or had nondeliverable letters, leaving 10,909 participants.

The Social and Economic Science Research Center (SESRC) at Washington State University performed a mixed-mode, web-mail-telephone survey of mothers using methods developed by Dillman (36). Mothers who did not complete the Web questionnaire were sent a mail questionnaire with letters in English and Spanish to everyone with a $2 bill incentive in the first mailing and follow-ups to nonrespondents. Mothers who did not respond to the Web or mail questionnaires were invited to complete a telephone interview in English, Spanish, Russian or Vietnamese, with interviews ending on December 31, 2004.

DATA ANALYSIS

Bivariate tests compared the characteristics of children with and without completed questionnaires, excluding children whose mothers refused study participation. Pearson Chi-square test and ANOVA were performed to determine whether child and mother characteristics differed for Blacks, Hispanics and Whites.

We used linear models to estimate whether mothers’ RSDC was associated with the outcome, mothers’ ratings of their children’s oral health. We chose a linear regression model due to the ease of interpretation of results and use in prior studies of self-rated oral health (24, 37–39). Though the Likert-scale outcomes were not strictly continuous in nature, it has been shown that in large samples linear regression produced valid estimates (39).

Separate models were estimated for Black, Hispanic and White mothers. Models were estimated in three steps, initially entering child covariates, adding mother and family covariates, and finally entering propensity scores to attempt to correct for potential endogeneity between RSDC and child dental use (40–44). A RSDC is not a randomly assigned attribute, and mothers having a RSDC may differ from those who do not in observed and unobserved ways that also contribute to differences in their children’s oral health. We estimated the propensity of mothers having a RSDC as a function of age, race/ethnicity, income, education, employment status, dental insurance, marital status, mental health, preventive dental beliefs, dental fear, smoking status, immigrant status, survey mode, years in current residence and county, rural or urban residence, and county dentist-population ratio, and quintile RSDC propensity scores were added to the final model (45–47). Similar models were estimated using logistic regression for the dichotomous outcome of whether the child experienced tooth pain and whether dental health was rated fair or poor. Models were estimated using R version 2.2.1© 2005 statistical software.

Analyses were repeated for two racial/ethnic groups, American Indian and Asian mothers, in the fourth racial/ethnic group of the study’s disproportionate stratified sample. Because sample sizes are small, these analyses are exploratory.

RESULTS

Survey and Eligibility

In total, 4,762 parents completed either the Web (n=306), mail (n=3,329) or telephone (n=1,127) instruments. Of the remaining 6,147 parents (10,909 – 4,762= 6,147), 695 parents refused to participate, 86% of those when contacted by telephone after the Web and mail surveys. Another 4,387 households had non-deliverable addresses, non-working telephone numbers, or ineligible individuals; and 1,065 parents were unreachable, unable to interview (due to hearing difficulty, language barrier or disability), or deceased. The unadjusted response rate is 44% (4,762/10,909), and excluding the 4,387 households with ineligible individuals or inaccurate contact information, the adjusted response rate is 73% (4,762/6,522).

Compared to children without questionnaires (n=5,444), children with completed questionnaires (n=4,749) had similar characteristics but were more likely to have a Medicaid dental claim in January–April 2004 (43% versus 36%, p<.001) and be enrolled in ABCD (18% versus 13%, p<.001), and less likely to be from an American Indian tribe (3.6% versus 5.1%, p<.001).

After excluding respondents who were not mothers, 4,373 mothers remained. From those, we excluded nine whose children were Medicaid ineligible. We excluded from analyses 140 mothers who declined to specify their race, 114 who specified “other” race, and 160 who specified more than one race/ethnicity. Analyses were based on the remaining 3,874 mothers in the following racial/ethnic groups: Black (n=816), Hispanic (n=1309), White (n=1379), Asian (n=237), and American Indian (n=133).

Characteristics of Mothers and Children by Racial/Ethnic Group

Table 1 compares the personal characteristics of mothers and children by racial/ethnic group. Statistically significant differences exist for almost all of the characteristics across the Black, Hispanic and White racial/ethnic groups.

Table 1.

Personal Characteristics of Mothers and Children by Racial/Ethnic Group (Averages and Percentages)

| Black n = 816 |

Hispanic n = 1309 |

White n = 1379 |

p-value* | Asian n = 237 |

American Indian n = 133 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | ||||||

| Personal & Family Characteristics | ||||||

| Child’s age (in years; average ± SD)# | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 5 ± 1.2 | 0.001 | 4.9 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 1.2 |

| Female (%) | 50% | 50% | 47% | 0.292 | 51% | 52% |

| Household primary language not English (%) | 3% | 65% | 3% | 0.000 | 22% | 2% |

| Caregiver not U.S. citizen (%) | 0% | 1% | 2% | 0.001 | 1% | 0% |

| Dental Characteristics | ||||||

| Mother-rated dental health of child (average ± SD; 1–5 scale, 1=poor and 5=excellent)# | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 0.000 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.1 |

| Sometimes/frequently had dental pain (%) | 15% | 16% | 13% | 0.264 | 13% | 17% |

| High dental fear (%) | 11% | 23% | 12% | 0.000 | 23% | 15% |

| Enrolled in ABCD Program (%) | 4% | 25% | 22% | 0.000 | 10% | 21% |

| Has private insurance (%) | 17% | 10% | 16% | 0.000 | 20% | 24% |

| County Characteristics | ||||||

| Lives in Rural Zip code (%) | 2% | 39% | 22% | 0.000 | 2% | 36% |

| Medicaid dentists per 10K residents in county (average ± SD#) | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 0.000 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Mothers | ||||||

| Average Age | 30.7 ± 6.0 | 30.7 ± 6.0 | 31.2 ± 6.3 | 0.074 | 33.4 ± 6.4 | 31.2 ± 6.1 |

| Living Status | ||||||

| Mother living alone (%) | 68% | 22% | 37% | 0.000 | 25% | 39% |

| Immigration Status | ||||||

| Percent immigrants | 9% | 76% | 7% | 0.000 | 89% | 2% |

| Length of Residence | ||||||

| Years lived in county | ||||||

| <1 year | 3% | 3% | 4% | 0.006 | 5% | 4% |

| Between 1–2 years | 9% | 9% | 10% | 9% | 10% | |

| Between 3–5 years | 13% | 19% | 15% | 17% | 11% | |

| >5 years | 76% | 69% | 71% | 70% | 75% | |

| Years lived at same address | ||||||

| <1 year | 25% | 18% | 23% | 0.000 | 18% | 20% |

| Between 1–2 years | 39% | 32% | 32% | 28% | 26% | |

| Between 3–5 years | 23% | 28% | 24% | 28% | 23% | |

| >5 years | 12% | 23% | 21% | 26% | 31% | |

| Education | ||||||

| Did not finish high school | 12% | 49% | 11% | 0.000 | 13% | 17% |

| High school diploma or GED | 34% | 34% | 32% | 31% | 40% | |

| Some college or 2-year associate | 49% | 15% | 48% | 36% | 36% | |

| 4-year college degree or higher | 5% | 3% | 9% | 21% | 8% | |

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Employment full-time | 38% | 31% | 31% | 0.000 | 41% | 31% |

| Employed part-time or in school | 26% | 23% | 26% | 25% | 23% | |

| Homemaker | 12% | 29% | 30% | 22% | 21% | |

| Disabled | 6% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 2% | |

| Unemployed | 18% | 15% | 9% | 9% | 23% | |

| Dental insurance | ||||||

| None | 24% | 71% | 47% | 0.000 | 50% | 45% |

| Medicaid | 54% | 14% | 31% | 19% | 39% | |

| Private | 22% | 15% | 22% | 31% | 17% | |

| Annual Household income | ||||||

| <$10,000 | 56% | 44% | 37% | 0.000 | 38% | 51% |

| $10,000–$20,000 | 25% | 31% | 27% | 28% | 24% | |

| >$20,000 | 19% | 24% | 36% | 34% | 25% | |

| Cigarette Smoking | ||||||

| Some days or everyday (%) | 34% | 7% | 36% | 0.000 | 13% | 35% |

| Dental Beliefs/Fear | ||||||

| Mother believes dentist visits can prevent loose teeth | 57% | 73% | 62% | 0.000 | 72% | 60% |

| High dental fear (%) | 17% | 21% | 17% | 0.015 | 10% | 17% |

| Health | ||||||

| Mental health score | ||||||

| 1 (Best) | 16% | 19% | 10% | 0.000 | 14% | 11% |

| 2 | 38% | 41% | 44% | 36% | 49% | |

| 3 | 28% | 28% | 30% | 35% | 24% | |

| 4 | 13% | 8% | 13% | 12% | 9% | |

| 5–6 (Worst) | 5% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 7% | |

| Average self-rated dental health (average ± SD#; 1–5, 1=poor and 5=excellent) | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 0.000 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.3 |

| Survey Mode | ||||||

| Web | 6% | 3% | 10% | 0.000 | 6% | 6% |

| 73% | 63% | 72% | 84% | 77% | ||

| Telephone | 21% | 34% | 18% | 11% | 17% | |

SD = standard deviation

Statistical test is for difference across Black, Hispanic, and White racial/ethnic groups only

Overall, mothers rated their own dental health slightly less than good (avg 2.8, SD 1.2) on the 1-to-5 scale (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=very good, 5 = excellent). Hispanic mothers rated their dental health lower than Black and White mothers (p<.001), and the percentages of mothers rating their dental health as fair or poor had a similar pattern: 41% for Black mothers; 52% for Hispanic mothers; and 42% for White mothers (p < 0.001).

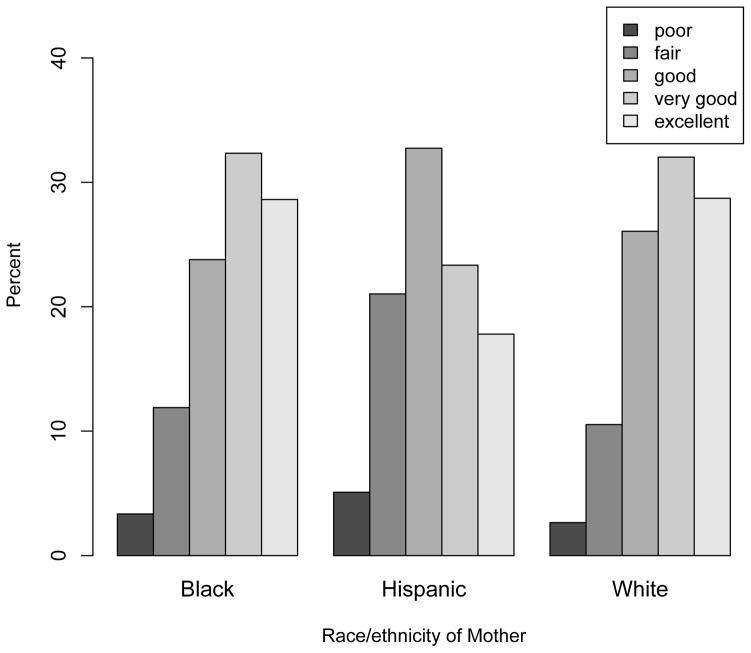

Overall, mothers’ ratings of their children’s dental health were higher and averaged 3.5 (SD 1.1). Hispanic mothers rated their children’s dental health significantly poorer than White or Black mothers, and the percentage of mothers rating their children’s dental health as fair or poor was higher for Hispanic mothers:15% for children of Black mothers; 13% for children of White mothers; and 26% for children of Hispanic mothers (p<.0001; see Figure 1). Mothers’ ratings of their children’s dental health are correlated modestly with self-ratings of their own dental health (r = .29; p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Mother’s Rating of Child’s Oral Health by Mother’s Race/ethnicity

Mothers’ reports of child dental pain were similar across racial/ethnic groups, with children of American Indian mothers having the highest reports of dental pain (17%). Mothers’ reports of child dental pain have a modest, inverse correlation (r = −0.11; p< 0.001) with self-ratings of their own dental health.

MOTHER RSDC AND CHILD DENTAL HEALTH

The percentage of mothers with a regular place of dental care is similar across racial/ethnic groups (Black, 39%; Hispanic, 40%; White, 39%; p = .59). About 39% of Asian mothers and 47% of American Indian mothers have a regular place.

Table 2 indicates the relationship between a mother’s regular source of care and her child’s dental health. Adjusting for mother and child characteristics, Black, Hispanic and White mothers with a RSDC rated their children’s dental health significantly higher than mothers without a RSDC, with estimates ranging between 0.15–0.20 across racial/ethnic groups in Models 1 and 2. After adding the propensity scores to the regression model, the sizes of the estimates attenuated slightly and were highly consistent, a uniform 0.15 across groups. The association observed among Black mothers was no longer significant at conventional levels (p=.09). There were no relationships between mother’s RSDC and the report of whether the child had dental pain, and between mother’s RSDC and whether mothers’ rating of the child’s dental health was fair or poor.

Table 2.

Adjusted Associations between Mothers Having a Regular Place of Dental Care and Mother Ratings of Their Young Children’s Dental Health, by Mothers’ Racial/Ethnic Group#

| Black Mothers (n=645) | Hispanic Mothers (n=901) | White Mothers (n=1116) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: adjusted for child variables only | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| estimate | 95%confidence interval | estimate | 95%confidence interval | estimate | 95%confidence interval | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mother-rated child dental health* | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.33 |

| Child’s dental health is fair or poor (OR)** | 0.72 | 0.45 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.26 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 1.06 |

| Child experienced tooth pain (OR)** | 1.03 | 0.66 | 1.6 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 1.21 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 1.12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Model 2: adjusted for child variables and mother variables | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| estimate | 95% confidence interval | estimate | 95% confidence interval | estimate | 95% confidence interval | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mother-rated child dental health* | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| Child’s dental health is fair or poor (OR)** | 0.78 | 0.48 | 1.27 | 0.93 | 0.65 | 1.33 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 1.16 |

| Child experienced tooth pain (OR)** | 1.11 | 0.70 | 1.76 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 1.27 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 1.22 |

|

| |||||||||

| Model 3: adjusted for child variables, mother variables, and propensity score | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| estimate | 95% confidence interval | estimate | 95% confidence interval | estimate | 95% confidence interval | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mother-rated child dental health* | 0.15 | −0.02 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.28 |

| Child’s dental health is fair or poor (OR)** | 0.85 | 0.51 | 1.40 | 0.90 | 0.62 | 1.29 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.28 |

| Child experienced tooth pain (OR)** | 1.06 | 0.66 | 1.70 | 0.87 | 0.57 | 1.34 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.24 |

Mother ratings of child dental health on 1–5 scale, 1=poor and 5=excellent); estimates are from linear regression models.

OR = odds ratio from logistic regression model. Confidence intervals not containing 1.00 indicate a significant association.

Depending on model, estimates are adjusted using children covariates (gender, age, dental fear, ABCD enrollment, immigrant status, primary language in the home, child has private dental insurance), mother covariates (age, dental insurance, income, education, employment status, immigrant status, marital status, smoking, dental fear, mental health, survey mode) and propensity scores.

Consistent with the more robust findings for Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites, the Asian mothers with a RSDC, on average, rated their children’s dental health higher than mothers without a RSDC by 0.14 (p=0.35). The average rating of child’s dental health by American Indian mothers with a RSDC was also higher by 0.14 (p= 0.46).

DISCUSSION

For young children in low-income families and covered by Medicaid, we found that low-income mothers who have a regular source of dental care rate the dental health of their young children higher than mothers without a RSDC, controlling for child and mother characteristics and the mothers’ propensity to have a regular source of dental care. A regular source of dental care is associated with a modest increase (0.15) in dental health on a 1–5 scale, where 1 means ‘poor’ and 5 means ‘excellent’ dental health. This difference can be interpreted as a net movement of one level up this health scale by 15% of the population. For a clinical comparison, in a national study of children aged 2–5 the presence of a carious tooth surface was associated significantly with 0.51 lower parental ratings of their children’s oral health, controlling for child and family characteristics, parent perceptions of the child’s need for dental care and other factors (24).

This relationship was found for children with Hispanic and White mothers, and for children with Black mothers the relationship was almost statistically significant. Pilot findings show the same relationship for American Indian and Asian families. These benefits are population-based and reaching large numbers of families would help improve the oral health of low-income children.

Mother’s RSDC may be linked to her young children’s oral health through several mechanisms, particularly the influence that a mother’s RSDC has on the child’s access to dental care, oral hygiene habits, and direct exposure to cariogenic bacteria. In prior analyses we found that having a mother with a RSDC at baseline is associated with greater odds of the child receiving dental care in the following year. For children receiving dental care, mothers’ RSDC was associated with a greater likelihood of the child receiving preventive services, (23) which may have reduced caries and produced the favorable ratings of their children’s dental health. In addition, Black, Hispanic and White mothers having a RSDC was associated consistently with better ratings of their own oral health, greater likelihood of a dental cleaning and less likelihood of tooth extraction, suggesting that a RSDC has oral health benefits for the mother that may extend to her young children (48). However, measuring RSDC when the child is older because of the way the study was designed potentially reduces the chances of seeing the particular benefits of caries reduction through reduction of vertical transmission. Our findings imply that population-based interventions to increase the percentage of low-income mothers with a RSDC may result in a modest increase in children’s oral health.

It is unclear from our study design whether mother RSDC causes better ratings of child dental health or clinical dental health. Because low-income mothers are not randomly assigned to a RSDC, associations between mother RSDC and child dental health may be due to factors that influence both the mother’s dental habits and the child’s, but statistical adjustment for the propensity of mothers to have a RSDC did not change the results and may dampen those concerns. However, propensity scores are not a perfect substitute for randomization because the scores are based only on observed variables in the data set to adjust for differences between mothers with and without a RSDC. Unobserved confounders may still exist that explain the RSDC-child dental health relationship (49). Second, the cross-sectional study design limits causal inference, but the possibility of reverse causation of child dental health affecting mother RSDC seems unlikely. Third, we lacked clinical measures of children’s dental health, but given evidence that parent ratings of their preschool children’s dental health are correlated with clinical measures, this may be less of a concern (24, 25). To address these issues, we recommend future studies with prospective designs and clinical measures, ideally randomizing low-income mothers without a RSDC to a RSDC intervention or usual care groups, and expanding the age range to include children under 3.

Due to survey nonresponse, it is unclear whether these findings are generalizable to the population of Medicaid children aged 3–6 in Washington state. Data do not exist to determine whether mothers who responded to the survey were different than mothers who did not respond, and we lack data about the perceived or clinical oral health of children without a completed questionnaire. Using Medicaid records, we compared the characteristics of children with versus without completed questionnaires, and most were not significantly different. However, compared to children with questionnaires, children without questionnaires were somewhat less likely to have Medicaid dental claims prior to the sampling date. If we assume that mother RSDC-child dental health effects are mediated partly by preventive dental visits, the RSDC effects on ratings of child dental health in the total population may be slightly smaller than in our sample. However, this assumption may not be accurate if children without questionnaires were more likely to have private dental insurance, which would reduce their likelihood of having Medicaid dental claims.

Black, Hispanic and White mothers also reported that 13–16% of their young children sometimes or frequently had dental pain, and 13–26% rated their children’s dental health as fair or poor. In contrast, mother RSDC was not associated with mother reports of child dental pain or fair-poor dental health.

We found that mothers’ dental health was much worse than children’s dental health. Over 41–58% of mothers in the three racial/ethnic groups rated the condition of their teeth as fair or poor across racial/ethnic groups, while 13–26% of mothers rated their children’s dental health as fair or poor – which is worse than the 11% found in a national survey of children aged 2–5 (24). Mothers also were dissatisfied with the dental care they received (50).

We also found that mother ratings of her own dental health are correlated with her rating of the child’s dental health. This association is not surprising because household income, mother education and other characteristics influence all family members in a similar way. These patterns suggest that if low-income, young children have good-to-excellent oral health, their oral health may be at risk to erode over the life course and ultimately resemble the 41–58% levels of fair or poor oral health in their mothers. Public health interventions are warranted to prevent higher levels of child oral health from declining as they age into adulthood.

We conclude that in our sample, low-income mothers who have a regular source of dental care rate the dental health of their young children higher than mothers without a RSDC, and this relationship is consistent across racial/ethnic groups. These findings suggest that increasing access to dental care for mothers during this critical period of child development may have oral health benefits for the child.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant No. DE14400 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH. We also wish to acknowledge the substantial contributions of Dretha Phillips, survey director, along with John Tarnai, Bruce Austin and staff from the Social and Economic Sciences Research Center at Washington State University, which performed the survey. We acknowledge and greatly appreciate the support received from Cathie Ott, Gary Coats, Margaret Wilson and other personnel in the Health and Recovery Services Administration, where the Medicaid Program is administered in the Department of Social and Health Services in Olympia, Washington. We also thank Ginny English and William Laaninen at WithinReach for their administrative assistance in processing the responses of parents opting out of the study. We also thank Alice Gronski for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

Interpretations of results are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent the official opinion of the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, Health and Recovery Services Administration, and WithinReach.

Contributor Information

David Grembowski, Email: grem@u.washington.edu.

Charles Spiekerman, Email: cspieker@u.washington.edu.

Peter Milgrom, Email: dfrc@u.washington.edu.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, NIDCR, NIH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 (Conference Edition, in Two Volumes) Washington, DC: Jan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltran ED, Barker LK, Canto MT, et al. Surveillance for dental caries, dental sealants, tooth retention, edentulism, and enamel fluorosis – United States, 1988–1994 and 1999 – 2002. MMWR. 2005;54(03, August 26):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton-Evans G, Eke PI, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Horowitz AM, Li CH. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2007;11(248) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ismail AI, Sohn W. The impact of universal access to dental care on disparities in caries experience in children. JADA. 2001;132(3):295–303. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caufield PW. Dental caries – a transmissible and infectious disease revisited: a position paper. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19(8):491–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kononen H, Jousimies-Somer H, Asikainen S. Relationship between oral gram negative anaerobic bacteria in saliva of the mother and the colonization of her edentulous infant. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:273–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattos-Graner RO, Zelante F, Line RC, Mayer MP. Association between caries prevalence and clinical, microbiological and dietary variables in 1.0 to 2. 5-year-old Brazilian children. Caries Res. 1998;32(5):319–23. doi: 10.1159/000016466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattos-Graner RO, Correa MS, Latorre MR, Peres RC, Mayer MP. Mutans streptococci oral colonization in 12–30-month-old Brazilian children over a one-year follow-up period. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61(3):161–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milgrom P, Riedy CA, Weinstein P, Tanner AC, Manibusan L, Bruss J. Dental caries and its relationship to bacterial infection, hypoplasia, diet, and oral hygiene in 6-to-36 month old children. Comm Dent Oral Epid. 2000;28(4):295–306. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan A, Morse DE, O’Sullivan DM, Tinanoff N. The relationship between bottle usage/content, age, and number of teeth with mutans streptococci in 6–24-month-old children. Comm Dent Oral Epid. 1998;26(1):12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karn TA, O’Sullivan DM, Tinanoff N. Colonization of mutans streptococci in 8- to 15-month-old children. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58(3):248–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorild I, Lindau-jonson B, Twetman S. Prevalence of salivary Streptococcus mutans in mothers and their preschool children. International Journal of Pediatric Dentistry. 2002;12(1):2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohler B, Andreen I, Jonsson B, et al. Effect of caries preventive measures on Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in selected mothers. Scand J Dent Res. 1982;90(2):102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1982.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohler B, Bratthall D, Krasse B. Preventive measures in mothers influence the establishment of the bacterium Streptococcus mutans in their infants. Arch Oral Biol. 1983;28(3):225–31. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(83)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohler B, Andreen I, Jonsson B. The effect of caries-preventive measures in mothers on dental caries and the oral presence of the bacteria Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in their children. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29(11):879–83. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohler B, Andreen I. Influence of caries-preventive measures in mothers on cariogenic bacteria and caries experience in their children. Arch Oral Biol. 1994 Oct;39(10):907–11. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brambilla E, Felloni A, Gagliani M, et al. Caries prevention during pregnancy: results of a 30-month study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129(7):871–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grembowski D, Andersen RM, Chen M. A public health model of the dental care process. Med Care Rev. 1989;46(4):439–96. doi: 10.1177/107755878904600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rayner JF. Socioeconomic status and factors influencing the dental practices of mothers. Am J Public Health. 1970;60(7):1250–58. doi: 10.2105/ajph.60.7.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milgrom P, Mancl L, King B, Weinstein P, Wells N, Jeffcott E. An explanatory model of the dental care utilization of low-income children. Med Care. 1998;36(4):554–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu KT. Usual source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor vs. a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1509–29. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grembowski D, Spiekerman C, Milgrom P. Linking Mother and Child Access to Dental Care. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):e805–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talekar BS, Rozier G, Slade GD, Ennett ST. Parental perceptions of their preschool-aged children’s oral health. JADA. 2005;136(3):364–72. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohn W, Taichman LS, Ismail AI, Reisine S. Caregiver’s perception of child’s oral health status among low-income African Americans. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30(6):480–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis C, Mouradian W, Slayton R, Williams A. Dental insurance and its impact on preventive dental visits for U.S. children. JADA. 2007;138(3):369–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hay JW, Bailit H, Chiriboga DA. The demand for dental health. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(13):1285–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starfield B. Evaluating the State Children’s Health Insurance Program: critical considerations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:569–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham PJ, Trude S. Does managed care enable more low income persons to identify a usual source of care? Med Care. 2001;39(7):716–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grembowski D, Milgrom PM. Increasing access to dental care among Medicaid preschool children: the access to baby and child dentistry (ABCD) Program. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(5):448–59. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.5.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Drilea SK. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Research Findings No. 3. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research; 1997. Access to Health Care – Sources and Barriers, 1996. AHCPR Publication No. 98-0001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grembowski D, Spiekerman C, Milgrom P. Disparities in regular source of dental care among mothers of Medicaid-enrolled preschool children. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18(4):789–813. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corah NL. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res. 1969;43:496. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skaret E, Milgrom P, Raadal M, et al. Factors influencing whether low-income mothers have a usual source of dental care. ASDC J Dent Child. 2001;68(2):136–9. 142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JFR, et al. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gift HC, Atchison KA, Drury TF. Perceptions of the natural dentition in the context of multiple variables. J Dent Res. 1998;77(7):1529–38. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770070801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atchison KA, Gift HC. Perceived oral health in a diverse sample. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11(2):272–80. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110021001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lumley T, Diehr P, Emerson S, Chen L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu Re Public Health. 2002;23:151–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ettner SL. The relationship between continuity of care and the health behaviors of patients: does having a usual physician make a difference? Med Care. 1999;37(6):547–55. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ettner SL. The timing of preventive services for women and children: the effect of having a usual source of care. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(12):1748–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schur CL, Albers LA, Berk ML. Healthcare use by Hispanic adults: financial vs. non-financial determinants. Health Care Financing Review. 1995;17(2):71–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudor JM, Levitz GS. Visits to the physician: an evaluation of the usual-source effect. Health Serv Res. 1985;20(5):579–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambrew JM, DeFriese GH, et al. The effects of having a regular doctor on access to primary care. Med Care. 1996;34(2):138–51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. [Web site accessed on January 25, 2006];Rural-urban commuting area codes, 2000 ZIP code data. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/RuralUrbanCommutingAreaCodes/

- 46.American Dental Association. Distribution of Dentists in the United States by Region and State, 2003. Chicago: American Dental Association; May, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afifi AA, Kotlerman JB, Ettner SL, Cowan M. Methods for improving regression analysis for skewed continuous or counted responses. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:95–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.082206.094100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grembowski D, Spiekerman C, Milgrom P. Regular source of dental care and the oral health, behaviors, beliefs and dental services of low-income mothers of young children. Community Dental Health. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Causal effects in clinical and epidemiological studies via potential outcomes: concepts and analytical approaches. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milgrom P, Spiekerman C, Grembowski D. Dissatisfaction with dental care among mothers of Medicaid-enrolled children. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2008;36(5):451–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]