Abstract

Noroviruses are a leading cause of gastroenteritis outbreaks globally. Several lines of evidence indicate that noroviruses can antagonize or evade host immune responses, including the absence of long-lasting immunity elicited during a primary norovirus exposure and the ability of noroviruses to establish prolonged infections that are associated with protracted viral shedding. Specific norovirus proteins possessing immune antagonist activity have been described in recent years although mechanistic insight in most cases is limited. In this review, we discuss these emerging strategies used by noroviruses to subvert the immune response, including the actions of two nonstructural proteins (p48 and p22) to impair cellular protein trafficking and secretory pathways; the ability of the VF1 protein to inhibit cytokine induction; and the ability of the minor structural protein VP2 to regulate antigen presentation. We also discuss the current state of the understanding of host and viral factors regulating the establishment of persistent norovirus infections along the gastrointestinal tract. A more detailed understanding of immune antagonism by pathogenic viruses will inform prevention and treatment of disease.

INTRODUCTION

Noroviruses comprise a genus in the Caliciviridae family and the human viruses in this genus are notable for their association with numerous and widespread gastrointestinal disease outbreaks. Specifically, human noroviruses are responsible for the majority of severe childhood diarrhea in regions of the world where a rotavirus vaccine has been implemented and they are the leading global cause of foodborne disease outbreaks [1–4]. Norovirus strains are segregated into genogroups and genotypes/clusters based on the sequence of their major capsid protein VP1 and regions within ORF1, with genogroup I (GI), GII, and GIV containing primarily strains associated with gastroenteritis in humans [5]. Murine noroviruses segregating into GV provide a vital small animal model for norovirus research considering their genetic, molecular, and pathogenic similarities to their human counterparts [6–8].

Several lines of evidence from both human and murine norovirus studies strongly suggest that noroviruses encode mechanisms to circumvent host immune responses: First, early human volunteer studies demonstrated that a subset of people fail to mount lasting protective immunity against a homologous human norovirus challenge [9,10]. Consistent with this, primary murine norovirus infection results in suboptimal immunity that wanes over time [11,12]. Second, although the symptoms of human norovirus infection resolve very quickly in healthy adults, affected individuals can continue to shed low levels of virus for several weeks, reflecting incomplete immune clearance. In fact, it is well-established that even asymptomatically infected individuals can shed human norovirus for extended periods of times, and one recent study reported that shedding duration was similar between symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects [13–15]. This apparent persistent infection is much more pronounced in risk groups including infants, young children, immunocompromised, and transplant patients [16–19]. Likewise, some murine norovirus strains establish persistent infections, with virus remaining detectable primarily in the large intestine for several months post-infection [20–22]. Notably though, highly genetically related intra-cluster murine norovirus strains differ substantially in both induction of adaptive immune responses [12,23] and persistence establishment [20,21], providing highly valuable comparative tools to identify viral determinants of immune antagonism. In this review, we will summarize a growing body of literature describing specific norovirus mechanisms that antagonize host immune responses.

Noroviruses are small, non-enveloped, positive sense RNA viruses with genomes of ~ 7.5 kb [24]. The 5′ proximal open reading frame ORF1 encodes a polyprotein which is cleaved by the viral protease (Pro) into six nonstructural proteins: 1) NS1/2, also referred to as p48 for human noroviruses; 2) NS3, an NTPase; 3) NS4, also referred to as p22 for human noroviruses; 4) NS5, the VPg protein that is covalently attached to viral RNA molecules; 5) NS6, the viral Pro; and 6) NS7, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). ORF2 and ORF3 are translated from a subgenomic RNA, giving rise to the structural proteins VP1 and VP2, respectively [25,26]. Murine noroviruses express an additional protein called virulence factor 1 (VF1) from an alternative reading frame within ORF2, designated ORF4 [20,27]. The p22, p48, VF1, and VP2 proteins have all been described to possess immune-antagonizing activities (VF1 and VP2), or activities with a high likelihood of impeding immune responses (p22 and p48), and will be the focus of this review.

Impairment of protein trafficking pathways by human norovirus p48 and p22 nonstructural proteins

Many gastrointestinal pathogens disrupt the secretory pathway in intestinal epithelial cells, altering the balance of ions and fluids between the epithelial barrier and the intestinal lumen and thus contributing to diarrheal disease symptoms [28]. The main purpose of encoding proteins that interfere with cellular secretion pathways is likely to facilitate microbial replication but an unavoidable consequence of this activity is the impairment of vital host cell functions including those necessary for mounting immune responses at the cellular level. For example, cytokine secretion and surface expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules are both dependent on a functional protein trafficking pathway.

Two human norovirus proteins have been demonstrated to possess anti-secretory activity when overexpressed in cultured cells. First, the p48 nonstructural protein colocalizes with markers of the Golgi apparatus and induces Golgi rearrangement into discrete aggregates indicative of Golgi disassembly [29]. An independent study reported a vesicular staining pattern of fluorescently tagged p48 protein consistent with ER/Golgi localization [30]. Localization of p48 to the Golgi or vesicles did not require a predicted transmembrane domain at the carboxyl terminus of the protein, although this domain was sufficient to induce Golgi localization of a reporter protein [29,30]. Finally, p48 was revealed to bind vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A (VAP-A) that functions in SNARE-mediated vesicular transport and to block the transport of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G glycoprotein to the cell surface at a post-Golgi trafficking step [30]. Collective evidence thus strongly argues that the human norovirus p48 protein interferes with intracellular protein trafficking when overexpressed in cultured cells.

Second, the p22 nonstructural protein also contributes to Golgi disassembly and inhibition of the cellular secretory pathway [31]: Transient expression of fluorescently tagged p22 resulted in disassembly of the Golgi and inhibition of protein secretion as measured by a secreted alkaline phosphatase reporter assay. The p22 protein specifically blocked trafficking of COPII-coated vesicles from the ER to the Golgi. Notably, p22 contains a motif which closely resembles a well-defined ER export signal that is conserved across many human norovirus strains. Mutations in this motif ablated the ability of p22 to induce Golgi disassembly and inhibit protein secretion; moreover this motif could substitute for an established ER export signal. The murine norovirus p22 protein homologue called p18 does not contain this motif; although p18 did cause Golgi disassembly when expressed in 293T cells, it was less efficient at blocking the secretory pathway than human norovirus p22 [32]. Available evidence thus supports a model whereby p22 localizes to COPII-coated vesicles and prevents their fusion with the Golgi, ultimately leading to Golgi disassembly and impaired protein trafficking within the cell. Although the precise mechanism by which p22 alters normal trafficking of COPII-coated vesicles has not been elucidated, it requires a specific motif that has been coined a mimic of an endoplasmic reticulum export signal (MERES) [31,32].

Although the above-described studies examined the activity of p48 or p22 in overexpression systems, there is evidence supporting the notion that inhibition of host secretory pathways also occurs during norovirus infections: Transfection of Huh7 cells with human norovirus genomic RNA, and infection of permissive RAW 264.7 cells with a murine norovirus, both induce Golgi disassembly [31,33]. Murine norovirus replication complexes initially assemble on membranes derived from the ER, Golgi, and endosomes ultimately leading to accumulation of numerous cytoplasmic vesicles where intracellular replication occurs [33,34], supporting the idea that noroviruses hijack the secretory pathway for the purpose of assembling replication factories on cellular membranes. While it has yet to be determined whether the murine norovirus p48 and p22 homologues (referred to as NS1/2 and NS4, respectively) possess anti-secretory activity, they both localize to organelles involved in the secretory pathway so it is tempting to speculate that they promote replication complex formation on host membranes [35]. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that NS1/2 regulates the ability of a murine norovirus to efficiently infect the colon and establish a persistent infection at this site [36]. By consolidating in vitro observations of human norovirus p48 and in vivo observations of its murine norovirus homologue NS1/2, it is reasonable to speculate that norovirus persistence establishment is directly related to the anti-secretory (and possibly the related immune antagonist) activity of this nonstructural protein.

Overall data thus support a general model whereby specific norovirus nonstructural proteins localize to organelles of the host secretory pathway and encode mechanisms to impede normal trafficking within this pathway so that host membranes can be used as scaffolds for viral replication complex assembly. An unavoidable consequence of inhibiting vesicular transport within the secretory pathway is disassembly of the Golgi apparatus, which should affect the ability of the infected cell to mount an effective immune response (Fig. 1). Because caliciviruses share many commonalities with picornaviruses in terms of genetic structure, it is noteworthy that the picornavirus proteins 2B and 3A encoded in the same gene order as p48 and p22, respectively, also block host secretory pathways [37]. Moreover, 3A inhibition of host protein trafficking has been demonstrated to reduce cytokine secretion, and reduce surface expression of MHC class I molecules and tumor necrosis factor receptor, on infected cells [38–40].

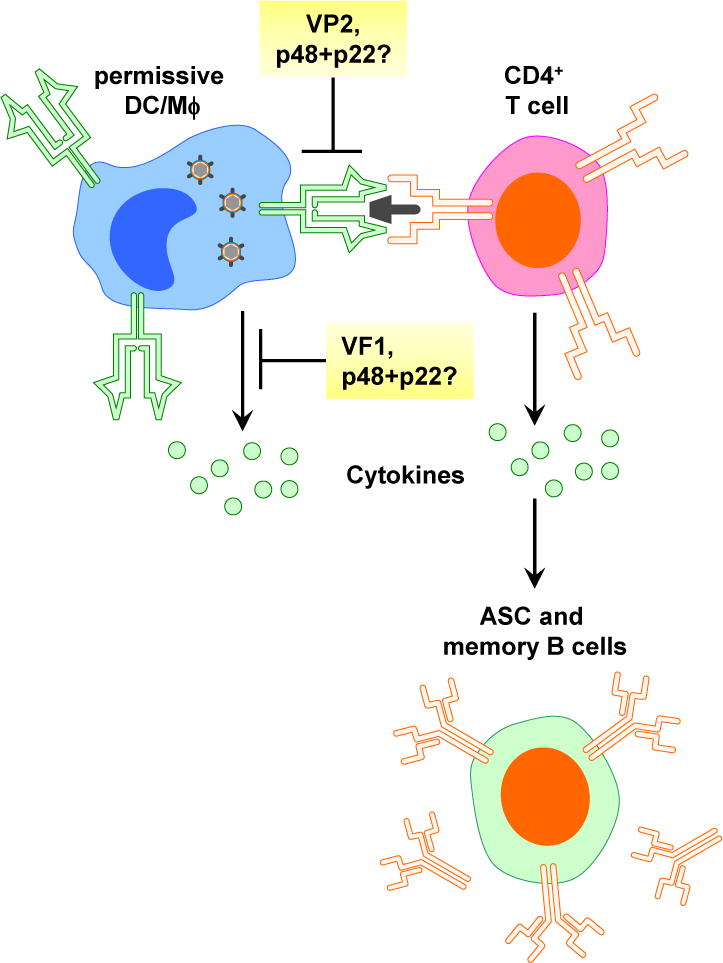

Figure 1. Norovirus proteins suppress antigen presentation and block cytokine induction, likely contributing to suboptimal memory immune responses and persistence establishment.

Noroviruses encode multiple immunoregulatory functions. First, the norovirus VP2 protein prevents infected macrophages from upregulating molecules necessary for antigen presentation, including MHC class I, MHC class II, and costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86. This activity regulates the induction of critical mediators of protective immunity including CD4+ T cells and antiviral antibody. Second, the norovirus VF1 protein blocks the induction of critical antiviral cytokines in infected cells, including type I IFN. This activity contributes to virulence and likely regulates the overall immune outcome to infection as well. Third, two norovirus nonstructural proteins, p48 and p22, inhibit host secretory pathways, a function that has been linked to immunoregulation for related virus families such as picornaviruses.

Although many enteric pathogens similarly target host secretory pathways in enterocytes and this can directly contribute to the induction of diarrhea due to an altered ion and fluid balance in the gut [28], a novel feature of noroviruses is their tropism for immune cells including macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells [33,41]. Thus, a major unresolved question is whether inhibition of secretory pathways by noroviruses contributes to diarrhea as it does for enterocyte-targeting pathogens. It is possible that noroviruses do infect enterocytes although this has yet to be replicated in vitro [42]. Alternative possibilities are that one or more nonstructural protein(s) are secreted from infected immune cells and interact with bystander enterocytes to mediate pathologic effects; enterocytes acquire viral proteins upon apoptosis of infected immune cells; or inhibition of the secretory pathway only occurs in infected immune cells and this process does not contribute to norovirus-induced diarrhea. Thus, future studies investigating the relevance of norovirus inhibition of host secretory pathways regarding both immune antagonism and pathogenesis are critical and can be accomplished using available norovirus animal models and novel viral cultivation systems [7,41,43,44].

Antagonism of cytokine induction by the murine norovirus VF1 protein

Murine noroviruses encode a fourth open reading frame overlapping with ORF2 that gives rise to the small VF1 protein [20,27]. Although human noroviruses do not encode a VF1 protein, sapoviruses – another Caliciviridae genus containing human viruses associated with gastroenteritis – do possess a similar ORF4 overlapping ORF2 [20]. The conservation of ORF4 in murine noroviruses and sapoviruses suggests that it plays a critical role in viral pathogenesis. Indeed, although VF1 expression from the subgenomic RNA is dispensable for murine norovirus infection in cultured cells, it does contribute to viral fitness since mutations disrupting ORF4 expression quickly revert to residues that restore expression upon repeated passaging in cells [27]. Moreover, mutation of VF1 results in attenuation in vivo: This is apparent in wild-type mice as demonstrated by reduced viral loads in animals infected with a VF1-mutant virus compared to parental wild-type virus; and in interferon (IFN)-deficient STAT1−/− mice as evidenced by substantially reduced levels of viral genome replication, delayed onset of weight loss, and a marked reduction in tissue pathology in animals infected with the mutant virus [27]. These data substantiate a critical role of VF1 in murine norovirus pathogenesis although it is dispensable in tissue culture.

McFadden et al. provided initial mechanistic insight into the function of VF1 by demonstrating that it localizes to the mitochondria and interferes with expression of antiviral genes including IFN-β, at least one IFN-stimulated gene (ISG54), and CXCL10 [27] (Fig. 1). This impairment occurs at the level of gene induction, as demonstrated by the ability of VF1 to significantly reduce IFN-β promoter activation in response to stimulation of type I IFN induction pathways that initiate in the mitochondria. The VF1 protein of a naturally attenuated murine norovirus strain called MNV-3 does not possess the ability to block IFN-β promoter activity while VF1 of the relatively more virulent MNV-1 strain does [12,45], revealing a correlation between VF1 antagonism of antiviral gene expression and virulence. In addition to blocking induction of antiviral genes, VF1 also controls virus-induced apoptosis: Infection of permissive RAW 264.7 cells with a VF1-mutant virus induced substantially higher levels of active caspase 3 than did infection with wild-type virus; this correlated with reduced viral protein synthesis late in infection although titers of infectious virus were unaffected [27]. Future studies will further probe the precise mechanisms by which VF1 antagonizes cytokine gene expression and regulates apoptosis pathways. Although human noroviruses do not encode a VF1, it will be interesting to test whether they have evolved unique strategies to accomplish similar antagonism of the host immune response and which viral gene products are responsible for interfering with type I IFN responses.

Prevention of antigen presentation by the murine norovirus VP2 protein

The icosahedral norovirus virion is composed of 90 dimers of the major capsid protein designated VP1 along with several copies of the minor capsid protein VP2 [26,46]. Recent data reveals that VP2 associates with a conserved motif within the shell domain of VP1 present on the interior surface of the capsid [47]. Based on its basic nature and internal location in the virion, VP2 is predicted to play a role in RNA binding and genome packaging into progeny virions [47]. VP2 has also been demonstrated to contribute to virion stability and increased expression and stability of the VP1 protein itself [48–50]. Finally, it negatively regulates the viral RdRp in a cell-based reporter assay for polymerase activity [51]. The expression of the norovirus VP2 protein is tightly regulated through a process termed translation termination-reinitiation occurring on the subgenomic RNA [52,53], which may reflect the importance of fine-tuning in relation to the multifactorial roles played by VP2 in the viral life cycle.

In addition to its functions in viral replication and virion stability, VP2 has also been implicated in modulation of the host immune response. As noted in the Introduction, highly genetically related intra-cluster murine norovirus strains induce remarkably variable levels of protective immunity. For example, MNV-3 induces substantially more robust antiviral antibody and CD4+ T cell responses that mediate protection from a secondary challenge when compared to MNV-1 [12]. This distinction correlates with induction of molecules involved in antigen presentation, including MHC and costimulatory molecules, on infected macrophages (Fig. 1). By generating chimeric murine noroviruses in which ORF3 genes were swapped between MNV-1 and MNV-3, we demonstrated that VP2 is primarily responsible for these differences: MNV-1 containing the MNV-3 ORF3 gene (MNV-1.3VP2) induces upregulation of antigen presentation molecules on macrophages and elicits protective immunity in contrast to parental MNV-1; whereas MNV-3.1VP2 is less efficient at inducing macrophage maturation and protective immunity compared to parental MNV-3 [12].

Although the mechanism by which VP2 regulates antigen presentation molecule upregulation on infected macrophages has not been elucidated, MNV-1 VP2 does not actively prevent MNV-3-induced maturation since maturation occurs in co-infected cells. This finding supports an evasion strategy in contrast to active antagonism, although this has yet to be proven. Moreover, although VP2 expression significantly regulates antigen presentation and protective immunity induction, chimeric MNV-1.3VP2 and MNV-3.1VP2 viruses displayed intermediate phenotypes compared to parental MNV-1 and MNV-3 so we assume that at least one more immunomodulatory mechanism contributes to these phenotypes. A likely candidate is VF1-mediated cytokine antagonism considering that MNV-3 induces increased levels of cytokines and chemokines in macrophages compared to MNV-1, and that the MNV-1, but not MNV-3, VF1 protein blocks IFN-β promoter activity [12]. Overall, the suboptimal induction of protective immunity by MNV-1 is likely due to VP2-mediated suppression of antigen presentation by classical antigen presenting cells (APCs) and VF1-mediated cytokine antagonism. This information should inform future vaccine design considering the weak and quickly waning protective immunity elicited by natural human norovirus infection [9,10]. Future research to determine the mechanism by which norovirus VP2 controls antigen presentation pathways is thus warranted.

Determinants of norovirus persistence establishment

Establishment of a persistent infection requires a virus to evade or actively antagonize the host immune response. The fact that noroviruses are capable of persistently infecting the intestine, as indicated by prolonged shedding and the indefinite maintenance of infectious virus in the colons of mice infected with certain murine norovirus strains [13–15,20,22], indicates that they must possess strategies to avoid elimination by host immune responses. The findings that MNV-1 encodes two immune antagonist activities (i.e. VF1-mediated antagonism of cytokine induction and VP2-mediated prevention of APC maturation) which are not active in MNV-3 [12] is in apparent contradiction to the rate of clearance of these two virus strains: While MNV-3 can establish a persistent infection, MNV-1 is cleared more rapidly [20,22]. These data beg the question why immune mediators induced by MNV-3 including antiviral antibody and CD4+ T cells [12] are insufficient to clear persistent infection. One clue may lie in observations by Tomov et al. that another persistent murine norovirus strain called MNV.CR6 induces a suboptimal CD8+ T cell response compared to MNV-1 [23]. Thus, it is possible that antiviral CD8+ T cells are required to control primary norovirus infections whereas antiviral antibody and CD4+ T cells mediate protective immunity. Distinct viral strategies may thus regulate the ability of noroviruses to establish persistent infection.

As mentioned above, the murine norovirus NS1/2 protein regulates colonic tropism and persistence establishment [36], possibly indicating a role for inhibition of host secretory pathways in persistence establishment. There is also evidence indicating a role for commensal bacteria in norovirus persistence establishment [54]. Commensal bacteria are known to stimulate norovirus infections in vitro and in vivo [41,54,55], and they appear to suppress the antiviral activity of type III interferon in a manner that is conducive to viral persistence [54]. This will be a rich area of future research building on the emerging theme that enteric viruses exploit commensal bacteria to enhance their own infectivity.

CONCLUSIONS

Considering the enormous amount of disease caused by human norovirus infections across the globe, developing prevention and treatment strategies is desperately needed. In order to infect their hosts and propagate themselves in vivo, viruses evolve strategies to antagonize host immune responses. These processes represent key targets for therapeutic and vaccine design since they are generally required for viral virulence. Several lines of evidence indicate that noroviruses circumvent host immunity, including the weak and quickly waning immunity elicited by a primary norovirus infection and the ability of these viruses to establish prolonged infections. Numerous research groups are making progress on elucidating norovirus mechanisms of immune antagonism, the focus of this review. In particular, two nonstructural proteins called p48 and p22 block the host secretory pathway which likely prevents cytokine secretion and expression of antigen presentation molecules on the cell surface; the VF1 protein antagonizes the expression of antiviral genes; and the VP2 protein suppresses antigen presentation and overall protective immunity induction. Further dissection of the mechanisms used by these individual proteins to evade clearance by the host immune response should lead to development of novel strategies to prevent infection by these important human pathogens. Moreover, understanding the precise mechanisms by which the viral nonstructural NS1/2 protein and commensal bacteria regulate the ability of noroviruses to establish persistent enteric infection will be an exciting area of future discovery.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Norovirus infections fail to elicit long-lasting robust immunity.

Noroviruses are shed for prolonged times, suggesting incomplete immune clearance.

Noroviruses block the host secretory pathway which likely impedes immune responses.

The norovirus virulence factor 1 (VF1) protein antagonizes cytokine induction.

The norovirus minor structural protein VP2 suppresses antigen presentation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH 1R01AI116892.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, Verhoef L, Premkumar P, Parashar UD, Koopmans M, Lopman BA. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:725–730. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo HL, Neill FH, Estes MK, Munoz FM, Cameron A, Dupont HL, Atmar RL. Noroviruses: The Most Common Pediatric Viral Enteric Pathogen at a Large University Hospital After Introduction of Rotavirus Vaccination. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2013;2:57–60. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pis070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne DC, Vinjé J, Szilagyi PG, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Chappell J, Bernstein DI, Curns AT, et al. Norovirus and Medically Attended Gastroenteritis in U.S. Children. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1121–1130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1206589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koo HL, Ajami N, Atmar RL, DuPont HL. Noroviruses: The Principal Cause of Foodborne Disease Worldwide. Discov Med. 2010;10:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroneman A, Vega E, Vennema H, Vinjé J, White PA, Hansman G, Green K, Martella V, Katayama K, Koopmans M. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch Virol. 2013;158:2059–2068. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karst SM, Wobus CE, Lay M, Davidson J, Virgin HW. STAT1-Dependent Innate Immunity to a Norwalk-Like Virus. Science. 2003;299:1575–1578. doi: 10.1126/science.1077905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karst SM, Wobus CE, Goodfellow IG, Green KY, Virgin HW. Advances in Norovirus Biology. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wobus CE, Thackray LB, Virgin HW. Murine Norovirus: a Model System To Study Norovirus Biology and Pathogenesis. J Virol. 2006;80:5104–5112. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02346-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrino TA, Schreiber DS, Trier JS, Kapikian AZ, Blacklow NR. Clinical immunity in acute gastroenteritis caused by Norwalk agent. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:86–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197707142970204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson PC, Mathewson JJ, DuPont HL, Greenberg HB. Multiple-challenge study of host susceptibility to Norwalk gastroenteritis in US adults. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:18–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu G, Kahan SM, Jia Y, Karst SM. Primary High-Dose Murine Norovirus 1 Infection Fails To Protect from Secondary Challenge with Homologous Virus. J Virol. 2009;83:6963–6968. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00284-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu S, Regev D, Watanabe M, Hickman D, Moussatche N, Jesus DM, Kahan SM, Napthine S, Brierley I, Hunter RN, et al. Identification of Immune and Viral Correlates of Norovirus Protective Immunity through Comparative Study of Intra-Cluster Norovirus Strains. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003592. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson T, Hutchings P, Palmer S. Outbreak of SRSV gastroenteritis at an international conference traced to food handled by a post-symptomatic caterer. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:157–162. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockx B, de Wit M, Vennema H, Vinjé J, de Bruin E, van Duynhoven Y, Koopmans M. Natural History of Human Calicivirus Infection: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:246–253. doi: 10.1086/341408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teunis PFM, Sukhrie FHA, Vennema H, Bogerman J, Beersma MFC, Koopmans MPG. Shedding of norovirus in symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S095026881400274X. FirstView. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frange P, Touzot F, Debré M, Héritier S, Leruez-Ville M, Cros G, Rouzioux C, Blanche S, Fischer A, Avettand-Fenoël V. Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Norovirus Fecal Shedding in Children with Inherited Immune Deficiencies. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1269–1274. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murata T, Katsushima N, Mizuta K, Muraki Y, Hongo S, Matsuzaki Y. Prolonged Norovirus Shedding in Infants under 6 Months of Age With Gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:46–49. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000247102.04997.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bok K, Green KY. Norovirus Gastroenteritis in Immunocompromised Patients. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2126–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1207742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green KY. Norovirus Infection in Immunocompromised Hosts. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thackray LB, Wobus CE, Chachu KA, Liu B, Alegre ER, Henderson KS, Kelley ST, Virgin HW. Murine Noroviruses Comprising a Single Genogroup Exhibit Biological Diversity despite Limited Sequence Divergence. J Virol. 2007;81:10460–10473. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00783-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu CC, Riley LK, Wills HM, Livingston RS. Persistent Infection with and Serologic Crossreactivity of Three Novel Murine Noroviruses. Comp Med. 2006;56:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias A, Bailey D, Chaudhry Y, Goodfellow IG. Development of a Reverse Genetics System for Murine Norovirus 3; Long-Term Persistence Occurs in the Caecum and Colon. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:1432–1441. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.042176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomov VT, Osborne LC, Dolfi DV, Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Mansfield K, Virgin HW, Artis D, Wherry EJ. Persistent Enteric Murine Norovirus Infection Is Associated with Functionally Suboptimal Virus-Specific CD8 T Cell Responses. J Virol. 2013;87:7015–7031. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03389-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green KY. Fields Virology. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2013. Caliciviridae:The Noroviruses; pp. 582–608. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes MK. Sequence and Genomic Organization of Norwalk Virus. Virology. 1993;195:51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glass PJ, White LJ, Ball JM, Leparc-Goffart I, Hardy ME, Estes MK. Norwalk Virus Open Reading Frame 3 Encodes a Minor Structural Protein. J Virol. 2000;74:6581–6591. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6581-6591.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.McFadden N, Bailey D, Carrara G, Benson A, Chaudhry Y, Shortland A, Heeney J, Yarovinsky F, Simmonds P, Macdonald A, et al. Norovirus Regulation of the Innate Immune Response and Apoptosis Occurs via the Product of the Alternative Open Reading Frame 4. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002413. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002413. This article was the first description of a norovirus virulence factor, and revealed that the VF1 protein blocks cytokine secretion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp TM, Estes MK. An inside job: subversion of the host secretory pathway by intestinal pathogens. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:464–469. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833dcebd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Vega V, Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, King AD, Mitra T, Gorbalenya A, Green KY. Norwalk Virus N-Terminal Nonstructural Protein Is Associated with Disassembly of the Golgi Complex in Transfected Cells. J Virol. 2004;78:4827–4837. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4827-4837.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30**.Ettayebi K, Hardy ME. Norwalk virus nonstructural protein p48 forms a complex with the SNARE regulator VAP-A and prevents cell surface expression of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. J Virol. 2003;77:11790–11797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11790-11797.2003. This article clearly demonstrated the anti-secretory activity of a norovirus p48 protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Sharp TM, Guix S, Katayama K, Crawford SE, Estes MK. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by norwalk virus nonstructural protein p22 requires a mimic of an endoplasmic reticulum export signal. PloS One. 2010;5:e13130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013130. This study was the first to report anti-secretory activity of the norovirus p22 protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharp TM, Crawford SE, Ajami NJ, Neill FH, Atmar RL, Katayama K, Utama B, Estes MK. Secretory pathway antagonism by calicivirus homologues of Norwalk virus nonstructural protein p22 is restricted to noroviruses. Virol J. 2012;9:181. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wobus CE, Karst SM, Thackray LB, Chang K-O, Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Krug A, Mackenzie JM, Green KY, Virgin HW. Replication of Norovirus in Cell Culture Reveals a Tropism for Dendritic Cells and Macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyde JL, Sosnovtsev SV, Green KY, Wobus C, Virgin HW, Mackenzie JM. Mouse Norovirus Replication Is Associated with Virus-Induced Vesicle Clusters Originating from Membranes Derived from the Secretory Pathway. J Virol. 2009;83:9709–9719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00600-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hyde JL, Mackenzie JM. Subcellular localization of the MNV-1 ORF1 proteins and their potential roles in the formation of the MNV-1 replication complex. Virology. 2010;406:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nice TJ, Strong DW, McCune BT, Pohl CS, Virgin HW. A Single-Amino-Acid Change in Murine Norovirus NS1/2 Is Sufficient for Colonic Tropism and Persistence. J Virol. 2013;87:327–334. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01864-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doedens JR, Kirkegaard K. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by poliovirus proteins 2B and 3A. EMBO J. 1995;14:894–907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dodd DA, Giddings TH, Kirkegaard K. Poliovirus 3A Protein Limits Interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and Beta Interferon Secretion during Viral Infection. J Virol. 2001;75:8158–8165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8158-8165.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neznanov N, Kondratova A, Chumakov KM, Angres B, Zhumabayeva B, Agol VI, Gudkov AV. Poliovirus Protein 3A Inhibits Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-Induced Apoptosis by Eliminating the TNF Receptor from the Cell Surface. J Virol. 2001;75:10409–10420. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10409-10420.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deitz SB, Dodd DA, Cooper S, Parham P, Kirkegaard K. MHC I-dependent antigen presentation is inhibited by poliovirus protein 3A. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:13790–13795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250483097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41**.Jones MK, Watanabe M, Zhu S, Graves CL, Keyes LR, Grau KR, Gonzalez-Hernandez MB, Iovine NM, Wobus CE, Vinjé J, et al. Enteric Bacteria Promote Human and Murine Norovirus Infection of B cells. Science. 2014;346:755–759. doi: 10.1126/science.1257147. This article reported the first cell culture system for a human norovirus by demonstrating that B cells are permissive to infection and commensal bacteria act as a co-factor for infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duizer E, Schwab KJ, Neill FH, Atmar RL, Koopmans MPG, Estes MK. Laboratory efforts to cultivate noroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:79–87. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkbeiner SR, Zeng X-L, Utama B, Atmar RL, Shroyer NF, Estes MK. Stem Cell-Derived Human Intestinal Organoids as an Infection Model for Rotaviruses. mBio. 2012;3:e00159–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00159-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foulke-Abel J, In J, Kovbasnjuk O, Zachos NC, Ettayebi K, Blutt SE, Hyser JM, Zeng X-L, Crawford SE, Broughman JR, et al. Human enteroids as an ex-vivo model of host–pathogen interactions in the gastrointestinal tract. Exp Biol Med. 2014;239:1124–1134. doi: 10.1177/1535370214529398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahan SM, Liu G, Reinhard MK, Hsu CC, Livingston RS, Karst SM. Comparative murine norovirus studies reveal a lack of correlation between intestinal virus titers and enteric pathology. Virology. 2011;421:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sosnovtsev SV, Green KY. Identification and Genomic Mapping of the ORF3 and VPg Proteins in Feline Calicivirus Virions. Virology. 2000;277:193–203. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vongpunsawad S, Prasad BVV, Estes MK. Norwalk Virus Minor Capsid Protein VP2 Associates within the VP1 Shell Domain. J Virol. 2013;87:4818–4825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03508-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertolotti-Ciarlet A, Crawford SE, Hutson AM, Estes MK. The 3′ End of Norwalk Virus mRNA Contains Determinants That Regulate the Expression and Stability of the Viral Capsid Protein VP1: a Novel Function for the VP2 Protein. J Virol. 2003;77:11603–11615. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11603-11615.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin Y, Fengling L, Lianzhu W, Yuxiu Z, Yanhua J. Function of VP2 protein in the stability of the secondary structure of virus-like particles of genogroup II norovirus at different pH levels: Function of VP2 protein in the stability of NoV VLPs. J Microbiol. 2014;52:970–975. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Chang K-O, Onwudiwe O, Green KY. Feline Calicivirus VP2 Is Essential for the Production of Infectious Virions. J Virol. 2005;79:4012–4024. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4012-4024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Subba-Reddy CV, Goodfellow I, Kao CC. VPg-primed RNA synthesis of norovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerases by using a novel cell-based assay. J Virol. 2011;85:13027–13037. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06191-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Napthine S, Lever RA, Powell ML, Jackson RJ, Brown TDK, Brierley I. Expression of the VP2 Protein of Murine Norovirus by a Translation Termination-Reinitiation Strategy. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luttermann C, Meyers G. Two Alternative Ways of Start Site Selection in Human Norovirus Reinitiation of Translation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11739–11754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54**.Baldridge MT, Nice TJ, McCune BT, Yokoyama CC, Kambal A, Wheadon M, Diamond MS, Ivanova Y, Artyomov M, Virgin HW. Commensal microbes and interferon-λ determine persistence of enteric murine norovirus infection. Science. 2015;347:266–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1258025. This study demonstrated that commensal bacteria are required for a norovirus to establish persistent infection, and provided mechanistic insight by identifying type III interferon as a key host determinant of this process. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kernbauer E, Ding Y, Cadwell K. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature. 2014;516:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature13960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]