Abstract

In delay discounting, temporally remote outcomes have less value. Cigarette smoking is associated with steeper discounting of money and consumable outcomes. It is presently unclear whether smokers discount health outcomes more than non-smokers. We sought to establish the generality of steep discounting for different types of health outcomes in cigarette smokers. Seventy participants (38 smokers and 32 non-smokers) completed four hypothetical outcome delay-discounting tasks: a gain of $500, a loss of $500, a temporary boost in health, and temporary cure from a debilitating disease. Participants reported the duration of each health outcome that would be equivalent to $500; these durations were then used in the respective discounting tasks. Delays ranged from 1 week to 25 years. Smokers’ indifference points for monetary gains, boosts in health, and temporary cures were lower than indifference points from non-smokers. Indifference points of one outcome were correlated with indifference points of other outcomes. Smokers demonstrate steeper discounting across a range of delayed outcomes. How a person discounts one outcome predicts how they will discount other outcomes. These two findings support our assertion that delay discounting is in part a trait.

Keywords: delay discounting, impulsivity, self-control, smoking, cigarette

The leading cause of preventable death in the United States is cigarette smoking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Cigarette smoking costs an estimated $193 billion per year in the form of lost productivity and health care expenditures (CDC, 2008). While smoking is multiply controlled (Li, 2006), one variable that is commonly associated with smoking is impulsivity (e.g., Flory & Manuck, 2009; Mitchell, 1999; Nieva et al., 2011). Impulsivity encompasses several different phenomena (Broos et al., 2012; de Wit, 2008; Jentsch et al., 2014) and includes relative insensitivity to delayed outcomes, often referred to as impulsive choice.

Impulsive choice is encompassed by the process of delay discounting. Delay discounting refers to how delayed outcomes lose value (Ebert & Prelec, 2007; Mazur, 1987; Odum, 2011a). Specifically, discounting is hyperbolic: short delays produce relatively large decreases in value, whereas longer delays have proportionally less impact (Ebert & Prelec, 2007; Mazur, 1987; Myerson & Green, 1995). In humans, delay discounting is frequently assessed by having participants repeatedly choose between two outcomes: a smaller immediate outcome and a larger delayed outcome (see Du, Green, & Myerson, 2002). Within a block of choices, the amount of the smaller immediate outcome is manipulated across choice opportunities until an indifference point is determined. The indifference point is the amount of a smaller immediate outcome that is equal in value to the larger delayed outcome. Across blocks of trials, the delay to the larger later outcome is manipulated and indifference points are determined for each presented delay. The degree of discounting is the extent to which indifference points decrease as the delay to receiving the larger alternative increases. Impulsive choice is defined as a pattern of steep discounting (Odum, 2011a).

Delay discounting and cigarette smoking are highly related. Smokers discount delayed monetary gains more than do non-smokers (Baker, Johnson, & Bickel, 2003; Bickel, Odum, & Madden, 1999; Friedel, DeHart, Madden, & Odum, 2014; Heyman & Gibb 2006; Mitchell, 1999; Ohmura, Takahashi, & Kitamura, 2005; Reynolds & Fields 2012; Wing, Moss, Rabin, & George, 2012; see Mackillop et al., 2011 for review and meta-analysis). Smokers also discount delayed monetary losses more than do non-smokers (Baker et al., 2003). Additionally, smokers discount non-monetary outcomes (food and entertainment) more than do non-smokers (Friedel et al., 2014). Furthermore, the degree of discounting across different outcome types is correlated (Friedel et al., 2014; Odum, 2011b). For example, people who discount one type of outcome steeply tend to discount other types of outcomes steeply. These correlations point towards delay discounting being a trait-like construct (Odum, 2011b). Delay discounting also relates to the likelihood of initiating cigarette smoking (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009) and the likelihood of success in treatment for smoking cessation (Dallery & Raiff, 2007; Mueller et al., 2009). This link between discounting and smoking could be important in developing strategies for smoking prevention and treatment via methods to decrease discounting (Bickel, Yi, Landes, Hill, & Baxter, 2011; Morrison, Madden, Odum, Friedel, & Twohig, 2014).

Despite the clear evidence that smokers discount delayed tangible outcomes more steeply than non-smokers discount those same tangible outcomes (e.g., money), it is surprisingly unclear how smokers and non-smokers discount delayed health outcomes. Odum, Madden, and Bickel (2002) provided evidence that smokers more steeply discount temporary relief from a debilitating, incurable disease. Other studies, however, have found no difference between how smokers and non-smokers discount health outcomes (Baker et al., 2003; Johnson, Bickel, & Baker, 2007; Khwaja, Silverman, & Sloan, 2007). Baker et al. (2003) and Johnson et al. (2007) found no difference in the degree of discounting of overall health wellness between smokers and non-smokers. It is possible that the conflicting findings as to whether smokers and non-smokers differentially discount health are based on whether participants are discounting temporary cures (i.e., removing illness; Odum et al., 2002) or temporary changes in health (e.g., adding wellness; Baker et al., 2003).

There are, however, two other factors that could explain the divergence in the literature in regards to how smokers and non-smokers discount delayed health outcomes. The first factor relates to the type of health outcome and the procedures that were used across the studies to determine indifference points. Odum et al. (2002) used a questionnaire (Bickel et al., 1999) to establish indifference points for a temporary cure. Baker et al. (2003) and Johnson et al. (2007) used a variation of the titrating double limit procedure (Richards, Zhang, Mitchell, & de Wit, 1999) to establish indifference points for changes (increases and decreases) in health. The difference in these procedures may contribute to the differential outcomes across studies.

Another factor that could explain the differential results of these studies is differences in statistical power. Odum et al. (2002) found a statistically significant difference in how smokers and non-smokers discount delayed health outcomes. While post hoc, the significant difference indicates that the study was sufficiently powered. Baker et al. (2003) and Johnson et al. (2007) report many significant relations between delay discounting and smoking status (e.g., sign effects, magnitude effects). However, the higher degrees of discounting for health outcomes by smokers relative to non-smokers were not statistically significant. The authors calculated power, based on the nominal group differences, and reported that the studies were underpowered for these specific comparisons. A replication, with increased statistical power, may affirm the nominal differences in how smokers and non-smokers discount delayed health outcomes reported by Baker et al. (2003) and Johnson et al. (2007).

The present experiment was designed to compare discounting of delayed temporary cures (illness removal) and delayed temporary health boosts (wellness addition) in smokers and non-smokers. Across both health outcomes, the same procedure to determine indifference points was used. Participants were also asked about monetary gains and monetary losses as a commonly used measure of group differences between smokers and non-smokers (e.g., Baker et al., 2003). If smokers were generally more impulsive than non-smokers (Friedel et al., 2014; Odum, 2011b) then we would expect that smokers would more steeply discount both delayed health boosts and cures than non-smokers. An alternative possibility is that there are differences in how smokers and non-smokers discount delayed health cures (Odum et al., 2002) but no differences in how the groups discount delayed health boosts (Baker et al., 2003). In addition to the novel comparison of the relative degree of discounting for smokers and non-smokers, we also examined for the first time how discounting for health outcomes was related to discounting of other outcomes within individuals.

Method

Participants

Smokers (n = 38) and non-smokers (n = 32) were recruited for participation via flyers posted in the community, radio advertisements, and online postings in help-wanted classifieds. Potential participants initially contacted us by telephone or e-mail, depending on the type of advertisement seen, to determine if they qualified for the study. To qualify for the study, participants needed to be at least 21 years of age, occasionally drink alcohol, and meet one of the criteria to be classified as a smoker or non-smoker. Participants were classified as smokers if they smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day (CDC, 2006); participants were classified as non-smokers if they had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime (CDC, 2006). If participants qualified, they were invited to participate in the study.

Procedure

All portions of the procedure were conducted in a private office containing two desk chairs, a desk, and computer. Prior to beginning any experimental tasks, we obtained informed consent from each participant and answered any questions about the study procedures. The experimental tasks were controlled by a custom-written program using E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.). All experimental tasks were completed in one two-hour session. Upon completion of the study, participants were compensated $60 for their time. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Utah State University.

Biological Samples

After informed consent was obtained, participants provided three biological samples. The first sample was to verify smoking status and measured expired carbon monoxide (CO) using a Micro+ Smokerlyzer (Bedfont Scientific, LTD.). Smokers whose expired CO concentrations were less than 6 ppm (Bedfont Scientific, n.d.) and non-smokers whose expired CO concentrations were greater than 6 ppm were allowed to complete the study but were excluded from all data analyses. The second biological sample measured recent alcohol consumption. Blood alcohol level (BAL) was assessed with an FC 10 Breathalyzer (Lifeloc). Participants with a BAL greater than 0.000 were allowed to complete the study but were excluded from all data analyses. Three self-reported smokers were excluded: two based on CO and one based on BAL. All of the self-reported non-smokers met the CO and BAL requirements for inclusion. The final biological sample taken was saliva; data from that sample are not reported here.

Discounting Tasks

All participants completed two monetary delay-discounting tasks and two health-related delay-discounting tasks. Participants also completed four other delay-discounting tasks not related to the goals of this experiment and not reported here (manuscript in preparation; see unreported discounting tasks, below). The order in which the delay-discounting tasks were presented to participants was randomized.

In all tasks, discounting was assessed using the adjusting amount procedure initially developed by Du et al. (2002). Within a trial, participants indicated which of two options they would prefer: a smaller amount of an outcome available immediately or a larger amount of that same outcome available after a delay. The options were shown simultaneously on the screen, with the position of choice options alternating across trials. Participants indicated their choice by touching, via the touchscreen monitor, the option they would prefer. After each choice, a feedback message appeared on the screen that displayed, “You chose” followed by the text displayed on their desired choice alternative. For the first trial within a block of trials, the smaller immediate amount was set to half of the larger delayed amount. Across trials, the smaller immediate amount changed based on the participant’s choices. If a participant chose the smaller immediate option then on the next trial that option was made less desirable (for example, if a participant chose $250 immediately instead of $500 after a delay, then on the next trial the immediate amount would be $125). If a participant chose the larger delayed option then on the next trial the smaller immediate option was made more desirable (for example, if a participant chose $500 after a delay instead of $250 immediately, then on the next trial the immediate amount would be $375). The amount of the first adjustment in a block of trials was equal to 1/4 of the larger delayed amount. The amount of each subsequent adjustment was 1/2 of the previous adjustment. Thus, the first adjustment was 1/4 of the delayed amount, the second adjustment was 1/8 of the delayed amount, the third adjustment was 1/16 of the delayed amount, etc. A block consisted of 10 trials with a single delay to the larger delayed option. The amount of the smaller immediate option on the last trial in a block was taken as the indifference point for that delay. There were 6 blocks per discounting task and the delays in each block were presented in the following order: 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months, 5 years, and 25 years.

Prior to beginning the first assigned discounting task, participants were presented general instructions that applied to all tasks. The instructions read:

You will make your selection by touching the desired button. Please note that the choices will switch sides randomly across questions. The following choices are hypothetical and you will not receive the actual outcomes. There are no “right” or “wrong” answers. Please just pick the one that you prefer. Please sit comfortably in front of the computer and touch the screen to make your choice. If you have any questions, please ask the experimenter now. We will now practice a few trials.

Ten practice trials were then presented. Practice trials were with monetary gains only. In the first practice trial participants were asked to choose between $10 delivered immediately or $100 delivered after 1 day. After each practice trial the amount of the smaller option was increased by $10. The practice trials used a different adjustment procedure than that in the test trials to minimize influence on participants’ choices in test trials. Any questions the participants asked of the experimenter were answered by reiterating the relevant portion of the task instructions.

After the practice trials had been completed another instruction screen was presented, which read: “The experiment will now begin. If you have any questions, please ask the experimenter now. Touch the screen to continue.” As before, any questions participants asked of the experimenter were answered by reiterating the relevant portion of the task instructions. A touch on the screen initiated the presentation of one of the randomly selected discounting tasks. When the monetary discounting tasks were selected for presentation, they started immediately after the selection occurred. When the health discounting tasks were selected for presentation, there were breaks in the experimental program to allow the experimenter to read the specific task instructions (described below) to the participants.

Monetary gain

In the monetary gain discounting task, participants indicated their preferences for gaining $500 delivered after a delay or gaining a smaller amount of money delivered immediately. The amount of the smaller-immediate option was set to $250 on the first trial and the larger delayed option was a constant $500 across all trials. The text for the immediate choice alternative was “Gain $[adjusting amount] now” and the text for the delayed choice alternative was “Gain $500 in [delay].”

Monetary loss

In the monetary loss discounting task, participants indicated their preferences for losing $500 after a delay or losing a smaller amount of money immediately. This task was identical to the monetary gain task, with the exception that both outcomes were framed as losses. The amount of the smaller-immediate option was set to $250 on the first trial and the larger delayed option was a constant $500 across all trials. The text for each immediate choice alternative was “Lose $[adjusting amount] now” and the text for the delayed choice alternative was “Lose $500 in [delay].”

Temporary health boost

In the temporary health boost discounting task, participants indicated their preference for gaining a longer duration of temporary wellness (i.e., 10% better health) after a delay or gaining a smaller amount of temporary wellness immediately. When this task was selected for presentation, the computer screen displayed the text, “Please contact the experimenter to continue.” When notified by the participant, the experimenter entered the room, advanced the program, and read aloud the task instructions that were displayed to the participant. The instructions used here are identical to the instructions used by Baker et al. (2003) except that the monetary amount used in this study was $500.Those instructions were:

I want you to think about your health over the past month. Now I want you to imagine that you have a choice between receiving some amount of money and temporarily feeling 10% better. That means you would feel more alert, have more energy, be physically stronger, have less body fat, and be less likely to become sick. However, this 10% increase in your health would only be temporary and then you would return to your current state of health. Receiving $500 right now would be just as attractive as experiencing how much time of 10% better health?

After finishing reading the task instructions to participants, the experimenter then asked, “In other words, if you had to pay $500 dollars to have 10% better health, how long do you think the 10% boost should last?” The rephrasing of the question displayed in the instructions was an attempt to ensure that all participants understood the instructions. Any remaining questions were answered by restating the relevant portions of the instructions or by reiterating the re-phrasing previously described. To provide a response to the question, participants were instructed to type a number and then choose the corresponding time unit: days, weeks, months, or years. This response (typing a value and selecting the unit for that value) was an analogue to the response used by Baker et al. (2003), in which participants wrote a value and then circled the unit on a sheet provided by the researchers. Once participants entered their response, the screen displayed the text: “You said that $500 for a 10% boost in your health should be: [number and time unit {for example, 6 weeks}] long. Press the ‘y’ button if this is correct. Press the ‘n’ button if this is incorrect.” The participant then made their response on the keyboard. If a participant responded on the “n” key then the instructions were displayed again and the process of entering a value and a time unit for that value was repeated. If the participant pressed the “y” key the delay-discounting portion of the task was initiated.

At the start of the delay discounting task the value of the larger delayed alternative was set to the participant’s response during the instruction portion of the task (e.g., 6 weeks of a boost) and the smaller immediate alternative was set to 1/2 of that value (e.g., 3 weeks of a boost). The text for the immediate choice alternative was “[adjusting duration] of a boost now” and the text for the delayed choice alternative was “[larger fixed duration] of a boost in [delay].” The portion of the instructions detailing the health boost was displayed centered and at the top of the screen during each trial.

Temporary cure

In the temporary cure discounting task, participants indicated their preference for gaining a longer duration of temporary illness removal after a delay or gaining a shorter duration of temporary illness removal immediately. The procedures for the temporary cure task were similar to those for the temporary health boost task, described above, with different instructions and different text during the discounting portion. This task was designed to be similar to Odum et al. (2002). The instructions read:

For the last 2 years, you have been ill because at some time in the past you had unprotected sex with someone you found very attractive, but whom you did not know. Thus, for the past 2 years, you have come down with a lot of colds and other ailments, some of which have required hospitalization. You have lost a lot of weight and are getting increasingly thin. Some friends do not come to see you anymore because of your disorder and those that do feel uncomfortable being with you. Imagine that without treatment you will feel this way for the rest of your life and that you will not die during any of the time periods described here. Receiving $500 right now would be just as attractive as experiencing how much time of a cure?

Participants indicated the duration of the cure that was equivalent to $500 as described above.

At the start of the delay discounting task the value of the larger delayed alternative was set to the participant’s response during the instruction portion of the task (e.g., 6 weeks of a cure) and the smaller immediate alternative was set to 1/2 of that value (e.g., 3 weeks of a cure). The text for the immediate choice alternative was “[adjusting duration] of a cure now” and the text for the delayed choice alternative was “[larger fixed duration] of a cure in [delay].”

Unreported delay discounting tasks

Participants also completed four discounting tasks to assess discounting of consumable commodities presented in a random order and as a whole block. This block of unreported discounting tasks was presented randomly either before or after the discounting tasks reported above. Data from the commodity discounting tasks are not presented here, because these tasks were administered for a separate study conducted at the same time.

Demographics Questionnaires

After completing all discounting assessments, participants reported their age, sex, race, ethnicity, monthly income, marital status, and highest level of education achieved. They then completed a series of questionnaires (described below) in the following order.

South Oaks Gambling Screen

The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987) consists of 36 items that assess gambling behavior (e.g., “In your lifetime, how often have you gone to a casino (legal or otherwise)?”). Responses on the questionnaire take a variety of forms (yes/no, frequency, etc.). Scores on the SOGS range from 0-20, with higher scores indicative of greater frequency of gambling and gambling-related problems. The internal consistency with our sample was acceptable (α = .74).

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) consists of 10 items and assesses frequency and amount of alcohol consumption, behavior related to drinking, and problems related to alcohol use (e.g., “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?”). The majority of responses are on a 5-point Likert scale, with 0 corresponding to the lowest frequency and 4 corresponding to the highest possible frequency. Scores on the AUDIT range from 0-40. The internal consistency of the items in our sample was acceptable (α = .81).

Eating Disturbance Scale

The Eating Disturbance Scale (EDS-5; Rosenvinge et al., 2001) consists of 5 items that measure beliefs about eating and problematic eating behaviors (e.g., “Are you happy with your eating habits?”). Responses occur along a 7-point Likert scale with 1 representing very satisfied or never and 7 representing very unsatisfied or everyday. Scores on the EDS range from 5-35. The internal consistency of the items in our sample was acceptable (α = .68).

Information Inventory

The Information Inventory (II; Altus, 1948) consists of 13 items and measures general knowledge base by asking a variety of questions in categories such as history, vocabulary, etc. (e.g., “How many inches are in a meter?”). All questions are open-ended. Scores on the inventory range from 0-30. The internal consistency of the items in our sample was acceptable (α = 0.71).

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) consists of 6 items and assesses severity of nicotine dependence in smokers (e.g., “How soon after waking do you smoke your first cigarette?”). The response format is multiple choice and yes/no. Scores on the survey range from 1-10. The internal consistency of the items in our sample was acceptable (α = .72). Only cigarette smokers completed this questionnaire.

Analysis

The Mazur (1987) hyperbola and Rachlin (2006) hyperboloid models were fit to the median group indifference points for each delayed outcome via curvilinear regression (Graphpad Prism®):

where V is the value of the delayed outcome, A is the amount of the delayed outcome, D is the delay to the outcome, k is the degree of discounting, and s is a scalar of delay. With the Rachlin (2006) model of delay discounting, s is constrained inclusively between the values of 0 and 1. The Mazur (1987) model is identical to the Rachlin (2006) model except it does not include the exponent s (which is functionally the same as s = 1). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974) was used to select the highest quality model for group data. AIC is a measure of the relative quality of a model that accounts for the tradeoff in the goodness of fit of a model and the complexity of that model. The smallest AIC value indicates the highest quality model. We did not use R2 to select the best fitting model because it is not an appropriate measure of goodness of fit for curvilinear models (see Johnson & Bickel, 2008 for discussion as this relates to delay discounting).

The highest quality model for the median indifference points per group (smokers vs. non-smokers) for each outcome (monetary gain, temporary cure, etc.) was then fit to the indifference points obtained from each participant for that group and outcome (see Franck et al., 2014). By convention (e.g., Myerson & Green, 1995), R2 was reported for individual participant data. We did not use the free-parameter k for statistical analysis because within the Rachlin hyperboloid (which was favored for some outcomes), k does not provide an independent measure of discounting due to its interaction with the s parameter. Analysis of k when only the Mazur (1987) model was fit to participant data (i.e., s was constrained to 1), without regard to which model provided a better fit to the data, produced a similar pattern of results for delay discounting differences as described below for indifference points but is not reported due to redundancy.

We also calculated the Effective Delay 50% (ED-50; Yoon & Higgins, 2008) for each group and outcome. An ED-50 is the delay at which the outcome has lost half of the present value (for the formulae used based on various models of discounting, see Franck, Koffarnus, House, & Bickel, 2015). This measure is helpful because it provides a metric of delay discounting that can be calculated for any model of delay discounting and is easily interpretable.

To investigate differences in the indifference points across groups and outcome type a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) was used as a repeated measures regression technique. GEE computes ANOVA-like pairwise comparisons for specific between- and within-group analyses. The pairwise comparisons are also Bonferroni corrected to account for multiple comparisons. GEE is appropriate for this analysis because it is robust against violations of normality, controls for the inter-correlation between dependent variables, and can examine between- and within-group differences within a single analysis (Hanley, Negassa, Edwardes,& Forrester, 2003). In effect, for these data the GEE is conceptually a more robust version of a repeated measures ANOVA. The use of GEE on indifference points provides higher power than a repeated measures ANOVA on k-values (as in Baker et al., 2003). All statistical analyses were conducted with Bonferonni corrections to ensure a constant familywise Type I error rate of α = .05.

Results

Demographic characteristics and questionnaire scores for smokers and non-smokers are reported in Table 1. Chi-squared tests did not reveal differences in the distribution of sex and ethnicity between smokers and non-smokers. The groups did differ on highest level of obtained education and AUDIT (problematic alcohol use) scores. The difference in scores on the Information Inventory approached conventional levels of statistical significance (t(69) = 1.80, p = .07). To be conservative in our analyses, these three variables (education, AUDIT and Information Inventory scores) were included as covariates in the GEE. There was no significant difference in the durations of health reported to be equivalent to $500 (i.e., the outcome being discounted) for the temporary cure or health boost scenarios (data not shown). There were also no significant differences in the durations of health reported to be equivalent to $500 by smokers and non-smokers (data not shown).

Table 1.

Non-smoker and smoker demographics

| Non-Smoker (SE) | Smoker (SE) | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | 90% | 81% | |

| Male | 57% | 70% | |

| Educationa | 3.33 (0.06) | 2.49 (0.18) | 2.81** |

| Age (years) | 37.10 (2.35) | 39.41 (2.11) | −0.73 |

| Monthly Income ($) | 2,155 (347.92) | 1,595 (338.85) | 1.14 |

| Information Inventory | 8.67 (0.67) | 7.24 (0.48) | 1.80 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test |

5.63 (0.71) | 14.51 (1.23) | −5.91*** |

| South Oaks Gambling Screen |

9.17 (1.15) | 8.97 (0.93) | 0.13 |

| Eating Disturbance Scale |

17.03 (1.30) | 17.62 (1.26) | −0.32 |

| Carbon Monoxide (ppm) | 1.79 (0.15) | 11.14 (0.69) | −12.51*** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < 0.001

Participants were asked about their highest level of obtained education: 1=did not complete high school, 2=high school degree or equivalent, 3=associate degree, 4=bachelors degree, 5=graduate degree, 6=doctorate degree or equivalent.

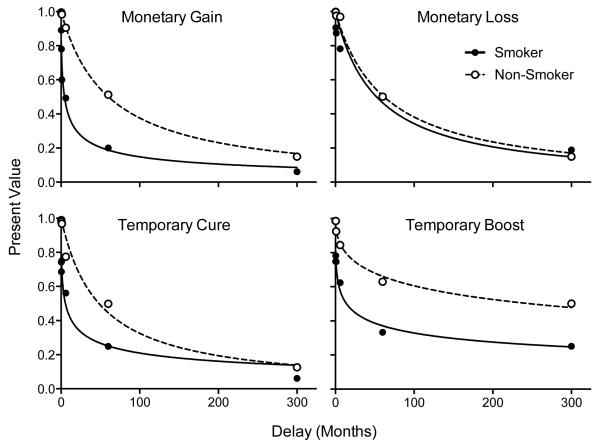

Figure 1 shows that median indifference points within each group and outcome decreased as the delay to receiving each outcome increased. In general, indifference points for smokers decreased more so with delay than did indifference points for non-smokers. To determine the highest quality model for the median indifference points for each outcome, the Mazur (1987) hyperbolic and Rachlin (2006) hyperboloid models were compared using AIC for group data. Median R2 for individual participant data are reported by convention. Table 2 displays the results of the model fit analyses for each group and discounting outcome. AIC favored the Rachlin hyperboloid model for four of the eight outcomes: non-smoker health boost, smoker money gain, smoker health cure, and smoker health boost. Median R2 values obtained from individual model fits were higher for the Rachlin hyperboloid for six of the eight outcomes; there was no difference in median R2 for the other two outcomes. For non-smokers the AIC scores indicated that the Mazur (1987) was the highest quality model for monetary gains, monetary losses, and temporary cures and the Rachlin (2006) was the highest quality model for temporary health boosts. For smokers, the Mazur (1987) was the highest quality model for monetary losses while the Rachlin (2006) was the highest quality model for monetary gains, temporary cures, and temporary health boosts.

Figure 1.

Median indifference points with lines of best fit. Model fits to the data from smokers and non-smokers for four delay discounting outcomes. Present value is expressed as a proportion of the undiscounted amount of the delayed outcome. For each line, the highest quality model is shown. See text and Table 2 for model selection.

Table 2.

Model fit comparisons of Mazur (1987) and Rachlin (2006) to group (AICc) and individual indifference points (R2)

| Group AICc |

Individual R2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Mazur (1987) |

Rachlin (2006) |

Mazur (1987) |

Rachlin (2006) |

|

| Non-Smoker | Money Gain | −48.46 | −38.46 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Money Loss | −35.89 | −25.89 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| Health Cure | −27.38 | −20.53 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| Health Boost | −20.67 | −26.76 | 0.70 | 0.95 | |

| Smoker | Money Gain | −17.86 | −18.05 | 0.74 | 0.91 |

| Money Loss | −22.92 | −21.84 | 0.80 | 0.88 | |

| Health Cure | −14.41 | −15.38 | 0.49 | 0.87 | |

| Health Boost | −12.71 | −21.43 | 0.69 | 0.86 | |

Values in bold indicate the higher quality model (AIC – Akaike Information Criterion) or best fitting model (R2). AIC scores reflect median group indifference points. For AIC, the lowest value indicates the superior model. R2 values are the median R2 values obtained from fitting each model to each participant’s indifference points.

Table 3 includes the parameter estimates for the highest quality model for each group and outcome (see Franck, Koffarnus, House, & Bickel, 2015). The parameters in Table 3 were those used to create the lines of best fit in Figure 1. In each comparison between smokers and non-smokers across outcomes, the fitted parameters showed steeper discounting by delay (larger k and greater ED-50%) by smokers than non-smokers.

Table 3.

Model fits and parameter estimates to median indifference points for the highest quality model

| Outcome | k | s | R 2 | ED-50% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smoker | Money Gain | 0.017 | - | 0.99 | 60.3 |

| Money Loss | 0.016 | - | 0.99 | 61.8 | |

| Health Cure | 0.021 | - | 0.97 | 48.2 | |

| Health Boost | 0.075 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 248.6 | |

| Smoker | Money Gain | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 4.3 |

| Money Loss | 0.019 | - | 0.93 | 52.2 | |

| Health Cure | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.94 | 5.5 | |

| Health Boost | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.97 | 14.1 |

Model fit values to median group indifference points. The s parameter is only reported when Rachlin (2006) was the higher quality model. See text and Table 2 for model selection. Effective Delay-50% (ED-50%) is the delay (expressed in months) at which half of the present value of the delayed outcome has been lost.

To identify differences in indifference points by outcome between- and within-groups, a GEE analysis was conducted (described in section 2.3). An auto-regressive correlation matrix for the GEE was chosen because of the observed trend of decreased correlation between indifference points as the temporal distance between those points increased. An exploratory GEE model was created that included main effects for education, AUDIT and Information Inventory scores. However, these variables were not significant predictors of adjusted mean indifference points for either group. In order to report the most parsimonious model, these measures were removed as main effects from the final model but remained as covariates for the post hoc adjusted mean indifference point pairwise comparisons. Participant sex was also included in the exploratory model but there was no main effect of sex and using sex as a covariate did not lead to any differences in the results of the GEE. For these reasons, sex was left out as both a factor and covariate in the final GEE model.

Smoking status and the commodity discounted influenced indifference points. In general, indifference points obtained from cigarette smokers were lower than indifference points obtained from non-smokers, indicated by a main effect of smoking status on indifference points (β = 0.18, z = 10.04, p < .01). This finding indicates that, on average, being a smoker resulted in a 0.18 decrease in the adjusted mean indifference point compared to the indifference point for a non-smoker, indicating smokers were more impulsive than non-smokers. In general, adjusted mean indifference points for all participants were affected by the outcome discounted, indicated by a main effect of outcome type on indifference points (β = 0.13, z = 7.78, p < .001). This β value should be interpreted with caution, as it only informs that there were differences between outcomes but it does not describe where those differences occurred. Pairwise comparisons (reported below) evaluate indifference points by outcome within smokers and non-smokers.

To investigate the differences across particular outcomes between smokers and non-smokers, pairwise comparisons were conducted. Table 4 reports adjusted mean indifference points for each group and commodity, differences between the groups for each outcome, and the corresponding statistical significance of those differences. Cigarette smokers had lower indifference points for monetary gains (MD = −0.16, p < .05), health cures (MD = −0.19, p < .01), and health boosts (MD = −0.18, p < .01) compared to non-smokers, indicating smokers were more impulsive for these outcomes. There was no significant difference between indifference points for smokers and non-smokers for monetary losses (MD = −0.05, p = .28).

Table 4.

Adjusted mean differences for indifference points by group and outcome

| Adjusted Mean Indifference Point (SE) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker | Non-smoker | Mean Difference | |

| Money Gain | 0.35 (0.04) | 0.53 (0.05) | −0.16 (0.06)* |

| Money Loss | 0.63 (0.04) | 0.68 (0.03) | −0.05 (0.05) |

| Health Cure | 0.56 (0.04) | 0.75 (0.04) | −0.19 (0.06)** |

| Health Boost | 0.73 (0.04) | 0.91 (0.04) | −0.18 (0.06)** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note: Comparisons are Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Information Inventory, and education scores included as covariates.

Within-group pairwise comparisons were conducted to determine differences in how each outcome was discounted. Table 5 contains the adjusted mean differences between each outcome within each group as well as the statistical significance of those differences. For both groups, the discounting of monetary gains was steeper than the discounting of monetary losses (ps < .001). For both groups, the discounting of a temporary cure was also discounted more steeply than a temporary boost in health (ps < .001). Finally, for both groups monetary gains were discounted more steeply than both temporary cures and temporary health boosts (ps < .001).

Table 5.

Adjusted mean differences for indifference points by outcome for each group.

| Mean Difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Money Loss | Health Cure | Health Boost | ||

| Non-smoker | Money Gain | −0.15*** | −0.22*** | −0.37*** |

| Health Boost | 0.22*** | 0.15*** | ||

| Health Cure | 0.07 | |||

| Smoker | Money Gain | −0.27*** | −0.20*** | −0.37*** |

| Health Boost | 0.10 | 0.16*** | ||

| Health Cure | −0.06a | |||

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < . 001

Note: Comparisons are Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Information Inventory, and education scores included as covariates. Values are the mean adjusted indifference point for the row minus the mean adjusted indifference point for the column. Lower values indicate higher rates of discounting for the row outcome. For example, the bottom most value, a, is the adjusted mean indifference point for health cures minus the adjusted mean indifference point for monetary losses for the smoker group.

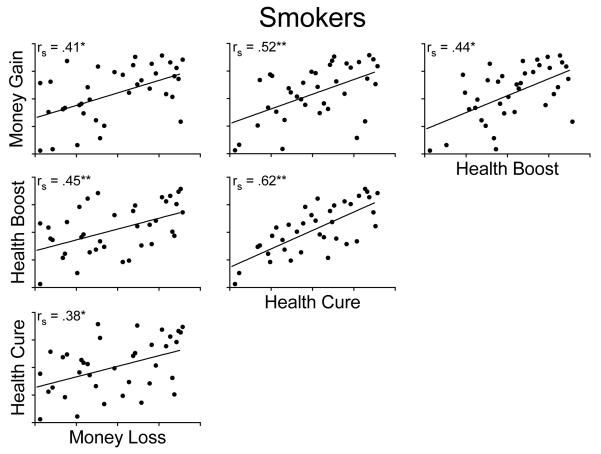

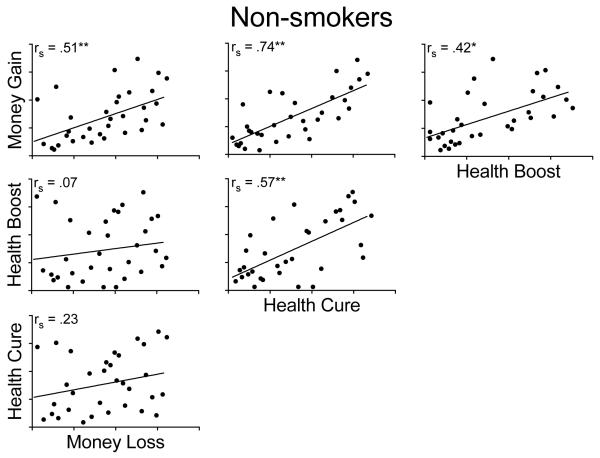

The correlation of discounting for one outcome to all other outcomes was completed with a partial correlation on the adjusted mean indifference point for both smokers (Figure 2) and non-smokers (Figure 3). Overall, indifference points across the four outcomes were highly positively correlated within groups, indicating that how participants discounted one outcome was related to how they discounted other outcomes. That is, a person who showed relatively steep discounting for one outcome was likely to show relatively steep discounting for another outcome, and similarly, a person who showed relatively shallow discounting for one outcome was likely to show relatively shallow discounting for another outcome. However, for non-smokers, discounting of delayed monetary losses was not associated with discounting of either temporary health cures or temporary health boosts.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of adjusted mean indifference point ranks for smokers with non-parametric Spearman’s Rho correlation reported and line of best fit. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Information Inventory, and education scores included as covariates. Axes on each figure are the rank of the mean adjusted indifference points. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01

Figure 3.

Scatterplots of adjusted mean indifference point ranks for non-smokers with non-parametric Spearman’s Rho correlation reported and line of best fit. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Information Inventory, and education scores included as covariates. Axes on each figure are the rank of the mean adjusted indifference points. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01

Discussion

In this study, we compared how cigarette smokers and non-smokers discounted qualitatively different types of health outcomes (i.e., temporary cures and temporary health boosts), monetary gains, and monetary losses. This is the first study to investigate how smokers and non-smokers discount qualitatively different health outcomes. We replicated the finding that smokers more steeply discount monetary gains and temporary cures than do non-smokers. We also found that smokers more steeply discount temporary health boosts when compared to non-smokers. This finding confirms the nominal but non-significant differences in discounting of health boosts that have been previously found between smokers and non-smokers (Baker et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2007). We also found correlations in steepness of discounting for monetary gains, monetary losses, health boosts, and temporary cures. These novel correlations extend our previous findings that how steeply a person discounts one tangible outcome correlates with how steeply that person discounts other tangible outcomes (Friedel et al. 2014; Odum, 2011b).

We found that smokers discount delayed monetary gains more than non-smokers do. When comparing delay discounting of smokers and non-smokers it is regularly found that smokers more steeply discount monetary gains than non-smokers (e.g., Bickel et al., 1999; MacKillop et al. 2011; Mitchell, 1999). The fact that we were able to replicate this well-supported finding illustrates that our measures were sensitive to the construct of interest and that we had appropriate power to detect significant differences in our dataset. We also found that smokers and non-smokers discount delayed monetary losses less steeply than delayed monetary gains. This replicates the common asymmetry in how delayed gains and losses are discounted for both smokers and non-smokers (e.g., Baker et al., 2003; Estle, Green, Myerson, & Holt, 2006; Johnson et al., 2007)

Our results provide evidence that smokers discount health consequences more steeply than non-smokers. Specifically, we found that both temporary cures and temporary boosts are discounted more steeply by smokers than by non-smokers. This replicates the findings of Odum et al. (2002) that smokers discount delayed health cures more than non-smokers. The finding that smokers also discount temporary health boosts more than non-smokers affirms the nominal difference reported by Baker et al. (2003) and Johnson et al. (2007). In this study, we find no evidence to support the alternative explanation that smokers more steeply discount delayed health cures but do not differentially discount delayed health boosts when compared to non-smokers.

Smokers are generally aware of the health risks associated with smoking (Oncken, McKee, Krishan-Sarin, O’Malley, & Mazure, 2005) and many advertising campaigns focused on changing smoking behavior have focused on the health benefits of quitting. One factor in the persistence of smoking, despite knowing the risks, seems to be the greater discounting of both the delayed negative health consequences associated with continued smoking and the delayed positive health consequences associated with abstinence. Perhaps advertising campaigns targeting smoking cessation would be better served with a message that focuses on both the temporally proximal as well as temporally distal consequences of smoking cessation. For example, an advertising campaign on smoking cessation could focus on factors like the more immediate decrease in the risk of heart attack and stroke (Lightwood & Glantz, 1997) as well as the long-term decrease in the risk of lung cancer.

These findings support and extend prior findings that smokers show a trait-like pattern of steep delay discounting across a variety of outcomes, including non-tangible health outcomes (the present study), consumable commodities (Friedel et al., 2014), and money (Bickel et al., 1999; Mitchell, 1999; Baker et al., 2003). How non-smokers discount one outcome is also correlated with how they discount other outcomes (see Charlton & Fantino, 2008; Odum, 2011b). These studies all support the notion that delay discounting is a trait-like phenomenon (Odum, 2011b) and that when a person steeply discounts one delayed outcome they are likely to steeply discount other types of delayed outcomes.

The understanding of delay discounting as a trait is consistent with the view that delay discounting is a trans-disease process (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Koffarnus, & Gatchalian, 2012). Delay discounting as a trans-disease process identifies that many people diagnosed with psychosocial disorders tend to have higher degrees of discounting. Delay discounting as a trait-like phenomenon is based on evidence that across different outcomes, how steeply a person discounts one outcome is highly related to how they discount other outcomes and that how steeply a person discounts is stable over long periods (e.g., Kirby, 2009).

The present study also provides supporting evidence that delay discounting is affected by state variables. A state variable is some environmental factor that affects behavior over a relatively short time frame (see Odum & Baumann, 2010). There are several environmental manipulations that can affect delay discounting. For example, Friedel et al. (2014) found that the type of consumable commodity affected the steepness of discounting in both smokers and non-smokers. Monetary gains and losses are also discounted differentially (e.g., Baker et al., 2003; the present study). Another state level variable that can affect delay discounting is how the hypothetical delays are framed. Framing the delay in terms of a concrete date in the future (for example, saying “January 1, 2030” instead of “25 years from now”) significantly decreases delay discounting (DeHart & Odum, 2015; Read, Frederick, Orsel et al., 2005). There is thus clear evidence that delay discounting has both trait-like features and state-based features.

One limitation of this experiment is the specific health outcomes that we used. We directly replicated the health tasks used by Odum et al. (2002), Baker et al. (2003), and Johnson et al. (2007). The health outcomes that were developed in these studies are relatively complex scenarios when compared to asking a participant to choose between a small amount of money and a large amount of money. The fact that we had to have experimenters available to ensure that the instructions for the health discounting tasks were understood provides some evidence of the relative difficulty of the task. The health boost outcome is also particularly nebulous when compared to the cure outcome: what does it mean to be and/or feel 10% better? Despite these complexities, the health discounting tasks result in orderly data that are similar in kind to other delay discounting data. Furthermore, the general findings with these tasks are replicable across studies and laboratories. Additionally, discounting of health outcomes is correlated with discounting of other outcomes. Despite these positive aspects of the procedures, development of simpler health discounting tasks could be helpful in future research.

Another possible limitation of this study is that all of the outcomes were hypothetical, as is common to use when outcomes are ethically or feasibly not possible to deliver (see Odum, 2011a). Furthermore, the participants did not likely have extensive experience with the health outcome scenarios. Most people are not routinely faced with scenarios in which they have a debilitating disease and must choose either a shorter duration of relief now or a longer duration of relief later. Despite this limitation of hypothetical outcomes, the delayed health outcomes were devalued in a hyperbolic like pattern similar to how other outcomes are devalued. Our study does not address the question as to whether hypothetical outcomes are discounted differently than real outcomes. However, there is evidence of strong similarities between discounting of hypothetical outcomes and real outcomes (Johnson & Bickel, 2002; Lagorio & Madden, 2005; Madden, Begotka, Raiff, Kastern, 2003; Madden et al., 2004). It is possible that choices for hypothetical outcomes may yet be found to lead to different degrees of discounting relative to choices for real outcomes. However, inasmuch as our participants are verbal organisms and verbal behavior can profoundly affect other behavior (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001) the verbal scenarios and consequences that are used in discounting tasks produce reliable results that do not seem to differ substantially from those made with actual outcomes where such comparison is possible.

Another limitation is that we found significant differences in alcohol consumption between smokers and non-smokers. This finding is problematic because alcohol usage is related to the degree of discounting. People who abuse alcohol more steeply discount delayed outcomes than control participants (e.g., Petry, 2001; Mitchell, Fields, D’Esposito, & Boettiger, 2005) and heavy drinkers discount delayed outcomes more than light drinkers (Vuchinich & Simpson, 1998). Alcohol use is also linked to cigarette smoking, in general. In this study, we found that smokers had higher overall AUDIT scores, indicating more problematic alcohol consumption. This replicates prior studies showing cigarette smokers tend to consume more alcohol than non-smokers (e.g., Carmody, Brischetto, Matarazzo, O’Donnell, & Connor, 1985; DiFranza and Guerrera, 1990) and that smokers tend to have more problematic drinking as measured by the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (Friedel et al., 2014). Within our analyses in this study, AUDIT scores were included as a covariate providing statistical control for the difference in alcohol usage. To separate the possible effects more clearly, future studies examining alcohol use and delay discounting could match participants based on cigarette usage, and studies examining cigarette smoking and delay discounting could match participants based on alcohol usage.

We also found significant differences in the highest level of formal education received between smokers and non-smokers. Some studies have found no difference in overall educational level between smokers and non-smokers (see Friedel et al., 2014) and between light and non-smokers (Johnson et al., 2007) or have matched education level between smokers and non-smokers (Bickel et al., 1999). However, other studies have found cigarette smokers have received less formal education than non-smokers (see, Ohmura et al., 2005; Flory & Manuck, 2009). There is also evidence that educational level is a predictor of the degree of discounting in smokers (Wilson et al., 2015). A difference in level of education could be particularly relevant in our study because, as we discussed above, the health outcomes were relatively complex. We did include educational level as a covariate in all of our analyses providing statistical control for the effects of education on discounting. A post-experimental comprehension test would have been useful to determine if there was some interaction between education level and comprehension of the health outcomes. Future studies that examine the discounting of health outcomes would benefit from matching participants based on education level.

Delay discounting is a potentially important measure for various psychosocial disorders (see Odum, 2011b; Bickel et al., 2012). As discussed above, the present study provides further support for the notion that smokers generally discount delayed outcomes more than non-smokers discount those same outcomes (see also Friedel et al., 2014). Delay discounting as a measure is important because it is predictive of cigarette use initiation (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009) as well as the likelihood of success for smoking cessation treatment (Dallery & Raiff, 2007; MacKillop & Kahler, 2009; Mueller et al., 2009). These findings also indirectly support efforts to develop methods that rapidly assess delay discounting (e.g., Gray, Amlung, Acker, Sweet & MacKillop 2014; Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014). Our findings support the idea that such an assessment provides a general measure of impulsive choice beyond the specific outcomes assessed. If delay discounting describes a persistent, trait-like pattern of behavior then efforts to change delay discounting (Bickel et al., 2011; Morrison et al. 2014) for one outcome should generalize to other outcomes. This is particularly important if addiction and other psychosocial vulnerabilities are related to excessive delay discounting (Bickel et al., 2012).

In conclusion, we found that smokers discount delayed health outcomes more steeply than do non-smokers, and that the degree to which a person discounts one outcome is highly related to the degree to which they discount other outcomes. This study extends our previous work (Friedel et al., 2014) and demonstrates that smokers are generally more impulsive for both tangible and non-tangible outcomes. Finally, this study supports our assertion that delay discounting describes a consistent pattern of behavior within an individual (Friedel et al. 2014; Odum, 2011b).

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grant R01DA029100 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The National Institute on Drug abuse had no role other than financial support.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All of the authors contributed in a significant way to this manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19(6):719–723. http://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 [Google Scholar]

- Altus WD. The validity of an abbreviated information test used in the Army. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1948;12(4):270–275. doi: 10.1037/h0055779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Wileyto EP. Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103(3):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: Similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(3):382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedfont Scientific LTD Micro+ smokerlyzer operating manual. (n.d.) Retrieved from www.bedfont.com. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: Emerging evidence. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2012;134(3):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the future: Working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(3):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broos N, Schmaal L, Wiskerke J, Kostelijk L, Lam T, Stoop N, et al. The relationship between impulsive choice and impulsive action: A cross-species translational study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36781–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TP, Brischetto CS, Matarazzo JD, O'Donnell RP, Connor WE. Co-occurrent use of cigarettes, alcohol, and coffee in healthy, community-living men and women. Health Psychology. 1985;4(4):323–335. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tobacco use among adults--United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(42):1145–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000-2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(45):1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(44):889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton SR, Fantino E. Commodity specific rates of temporal discounting: Does metabolic function underlie differences in rates of discounting? Behavioural Processes. 2008;77(3):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2007.08.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Delay discounting predicts cigarette smoking in a laboratory model of abstinence reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190(4):485–496. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart WB, Odum AL. The effects of the framing of time on delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103(1):10–21. doi: 10.1002/jeab.125. http://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology. 2008;14(1):22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Guerrera MP. Alcoholism and smoking. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1990;51(2):130–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Green L, Myerson J. Cross-cultural comparisons of discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Record. 2002;52(4):479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert JE, Prelec D. The fragility of time: Time-insensitivity and valuation of the near and far future. Management Science. 2007;53(9):1423–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Estle SJ, Green L, Myerson J, Holt DD. Differential effects of amount on temporal and probability discounting of gains and losses. Memory & Cognition. 2006;34(4):914–928. doi: 10.3758/bf03193437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory JD, Manuck SB. Impulsiveness and cigarette smoking. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(4):431–437. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181988c2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck CT, Koffarnus MN, House LL, Bickel WK. Accurate characterization of delay discounting: A multiple model approach using approximate bayesian model selection and a unified discounting measure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103(1):218–233. doi: 10.1002/jeab.128. http://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck CT, Koffarnus MN, House LL, Bickel WK. Accurate characterization of delay discounting: A multiple model approach using approximate Bayesian model selection and a unified discounting measure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103(1):218–233. doi: 10.1002/jeab.128. http://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel JE, DeHart WB, Madden GJ, Odum AL. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Discounting of monetary and consumable outcomes in current and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231(23):4517–4526. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3597-z. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-014-3597-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JC, Amlung MT, Acker JD, Sweet LH, MacKillop J. Item-based analysis of delayed reward discounting decision making. Behavioural Processes. 2014;103:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.01.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes M. D. deB., Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:364–75. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Plenum Press; New York: 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GM, Gibb SP. Delay discounting in college cigarette chippers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17(8):669–679. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280116cfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Ashenhurst JR, Cervantes MC, Groman SM, James AS, Pennington ZT. Dissecting impulsivity and its relationships to drug addictions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2014;1327:1–26. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12388. http://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77(2):129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. http://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F. Moderate drug use and delay discounting: A comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(2):187–194. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja A, Silverman D, Sloan F. Time preference, time discounting, and smoking decisions. Journal of Health Economics. 2007;26(5):927–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.02.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN. One-year temporal stability of delay-discount rates. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16(3):457–462. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.3.457. http://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.16.3.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK. A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: Accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22(3):222–228. doi: 10.1037/a0035973. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0035973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagorio CH, Madden GJ. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards III: Steady-state assessments, forced-choice trials, and all real rewards. Behavioural Processes. 2005;69(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.02.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2005.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144(9):1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MD. The genetics of nicotine dependence. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2006;8(2):158–164. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightwood JM, Glantz SA. Short-term economic and health benefits of smoking cessation: myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation. 1997;96(4):1089–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(3):305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Kahler CW. Delayed reward discounting predicts treatment response for heavy drinkers receiving smoking cessation treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104(3):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.020. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11(2):139–145. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.139. http://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Raiff BR, Lagorio CH, Begotka AM, Mueller AM, Hehli DJ, Wegener AA. Delay discounting of potentially real and hypothetical rewards: II. between- and within-subject comparisons. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12(4):251–261. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.251. http://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons M, Mazur J, Nevin JA, Rachlin H, editors. Quantitative analysis of behavior. Vol. 5 The effect of delay and intervening events on reinforcement value. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, N.J.: 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D'Esposito M, Boettiger CA. Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(12):2158–2169. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191755.63639.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KL, Madden GJ, Odum AL, Friedel JE, Twohig MP. Altering impulsive decision making with an acceptance-based procedure. Behavior Therapy. 2014;45(5):630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller ET, Landes RD, Kowal BP, Yi R, Stitzer ML, Burnett CA, Bickel WK. Delay of smoking gratification as a laboratory model of relapse: Effects of incentives for not smoking, and relationship with measures of executive function. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20(5-6):461–473. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283305ec7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L. Discounting of delayed rewards: Models of individual choice. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995;64(3):263–276. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieva G, Valero S, Bruguera E, Andión Ó, Trasovares MV, Gual A, Casas M. The alternative five-factor model of personality, nicotine dependence and relapse after treatment for smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(10):965–971. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL. Delay Discounting: I’m a k, you’re a k. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2011a;96(3):427–439. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423. http://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL. Delay discounting: Trait variable? Behavioural Processes. 2011b;87(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2011.02.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Baumann AAL. Delay discounting: State and trait variable. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WG, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. APA Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Discounting of delayed health gains and losses by current, never- and ex-smokers of cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(3):295–303. doi: 10.1080/14622200210141257. http://doi.org/10.1080/14622200210141257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura Y, Takahashi T, Kitamura N. Discounting delayed and probabilistic monetary gains and losses by smokers of cigarettes. Psychopharmacology. 2005;182(4):508–515. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0110-8. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-005-0110-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken C, McKee S, Krishnan-Sarin S, O'Malley S, Mazure CM. Knowledge and perceived risk of smoking-related conditions: A survey of cigarette smokers. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40(6):779–784. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.024. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154(3):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. http://doi.org/10.1007/s002130000638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Notes on discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85(3):425–435. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.85-05. http://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2006.85-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read D, Frederick S, Orsel B, Rahman J. Four score and seven years from now: The date/delay effect in temporal discounting. Management Science. 2005;51(9):1326–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Levin FR, Evans SM. Alcohol increases impulsivity and abuse liability in heavy drinking women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20(6):454–465. doi: 10.1037/a0029087. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0029087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Fields S. Delay discounting by adolescents experimenting with cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2012;107(2):417–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03644.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03644.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1999;71(2):121–143. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121. http://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenvinge JH, Perry JA, Bjørgum L, Bergersen TD, Silvera DH, Holte A. A new instrument measuring disturbed eating patterns in community populations: development and initial validation of a five-item scale (EDS-5) European Eating Disorders Review. 2001;9(2):123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6(3):292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. http://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.6.3.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AG, Franck CT, Mueller ET, Landes RD, Kowal BP, Yi R, Bickel WK. Predictors of delay discounting among smokers: Education level and a utility measure of cigarette reinforcement efficacy are better predictors than demographics, smoking characteristics, executive functioning, impulsivity, or time perception. Addictive Behaviors. 2015:1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.027. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing VC, Moss TG, Rabin RA, George TP. Effects of cigarette smoking status on delay discounting in schizophrenia and healthy controls. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.08.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Higgins ST. Turning k on its head: Comments on use of an ED50 in delay discounting research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95(1-2):169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.011. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]