Summary

Bacillus subtilis provides a model for investigation of the bacterial cell envelope, the first line of defense against environmental threats. Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors activate genes that confer resistance to agents that threaten the integrity of the envelope. Although their individual regulons overlap, σW is most closely associated with membrane-active agents, σX with cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance, and σV with resistance to lysozyme. Here, I highlight the role of the σM regulon, which is strongly induced by conditions that impair peptidoglycan synthesis and includes the core pathways of envelope synthesis and cell division, as well as stress-inducible alternative enzymes. Studies of these cell envelope stress responses provide insights into how bacteria acclimate to the presence of antibiotics.

The transcriptional specificity of RNA polymerase (RNAP) can be modified by replacement of the primary sigma (σ) subunit with alternative σ factors that modify promoter selectivity [1]. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) family of σ factors were originally described as a group of related alternative σ factors from diverse bacteria [2]. Structurally, they are smaller in size than the primary σ factor and contain only two of the four major conserved sequence regions of bacterial σ factors. Regions 2 and 4 correspond to the domains that bind the σ factor to the core RNAP and mediate recognition of the −35 and −10 promoter elements. Detailed phylogenomic analyses have revealed that the ECF σ factor family is extremely diverse [3,4]. In many species, ECF family proteins are the most numerous alternative σ factors with >50 paralogs in a single genome.

As reflected in their name, ECF σ factors most commonly regulate functions related to the cell envelope. The two representatives in Escherichia coli, σE and σFecI, are amongst the best characterized and control functions related to outer membrane homeostasis and ferric citrate uptake, respectively [5]. Comparable homologs are widespread in the proteobacteria. Bacillus subtilis encodes seven ECF σ factors and provides a contrasting view of ECF function in a Gram-positive model organism [6]. In B. subtilis, the σM, σW, σX and σV regulators each have roles in cell envelope homeostasis. In contrast, the other three ECF σ factors (σY, σZ, and σYlaC) are still poorly understood and will not be further considered. Here, I review the roles of the best characterized ECF σ factors in B. subtilis with an emphasis on recent insights into the nature of the σM envelope stress response.

The roles of ECF σ factors in Bacillus subtilis

The ECF σ factors of B. subtilis play an integral part in regulating the cell envelope stress responses (CESR) in this organism. CESR has been defined as that set of genetic responses induced by the presence of cell envelope active compounds [7], including the many antibiotics and bacteriocins commonly produced by members of the soil microbial community [8]. The responses regulated by ECF σ factors can therefore be reviewed within the larger context of CESR which additionally include systems activated by two-component systems and other regulators that regulate cell wall homeostasis. Well-characterized examples include the LiaRS, YtrA, WalKR, BceRS, and PsdRS systems [9-11].

Insights into the roles of the seven ECF σ factors encoded in the B. subtilis genome have been obtained primarily by studies of (i) phenotypes of mutant strains lacking one or more σ factor, (ii) the set of genes (regulon) controlled by each σ factor, and (iii) those stress conditions that activate each regulon. These studies have revealed that the seven ECF σ factors are individually and collectively dispensable for growth and sporulation [12,13]. A mutant strain lacking all seven ECF σ factors is more sensitive to numerous cell envelope stresses, including that elicited by antibiotics. This sensitivity is due primarily to the lack of σM, σW, σX and/or σV [13], which will therefore be the focus of this review. The critical role of these ECF σ factors in conferring resistance to antibiotics is also apparent from forward genetic experiments; selection for resistance to the β-lactam antibiotic cefuroxime led to recovery of a mutation in rpoC, encoding the β’-subunit of RNAP, that results in an increased activity of ECF σ factors [14].

General features of ECF σ factor regulons

The σM, σW, σX and σV factors are each encoded as the first gene of an operon in which the downstream gene encodes a membrane-localized anti-σ factor [3]. When cells experience an appropriate envelope stress the anti-σ factor is inactivated which leads to release of the σ and activation of the regulon [3,15,16]. The mechanisms of signal perception and the basis for anti-σ inactivation are not yet well understood, although substantial progress has been made in this area for both σW and σV [16,17], as reviewed below. Once released from the anti-σ, there is an autoregulatory promoter in front of the σ factor operon which serves to amplify the signal (positive autoregulation) and also increases expression of the anti-σ, presumably to allow a rapid shutoff of the response once the stress is relieved.

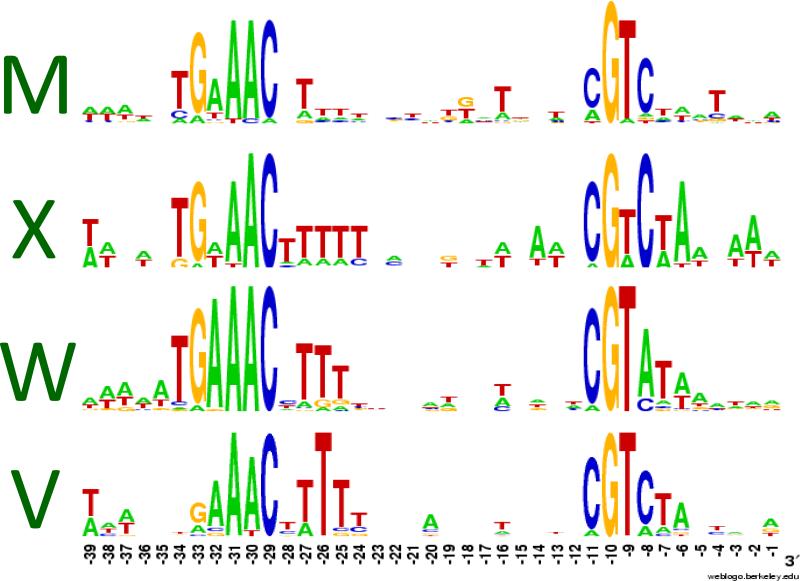

The regulons controlled by each of these four σ factors have been defined using transcriptomics (profiling of mRNA populations) in cells containing or lacking specific ECF σ factors in both unstressed and stressed conditions. These studies, complemented by in vitro transcription experiments, have allowed the definition of promoter consensus sequences for each ECF σ (Figure 1). The promoters recognized by each ECF σ factor are similar and are defined by characteristic sequence motifs near −35 and −10 relative to the transcription start site [18,19]. The regulons controlled by these four ECF σ factors overlap at the level of promoter recognition: some promoter sequences are specific for a single ECF σ factor whereas others can be recognized by more than one [13,20]. The rules governing promoter selectivity are emerging and have been an active topic of investigation, in part motivated by the possibility of using ECF σ factors as tools for synthetic biology [21]. In the case of the B. subtilis σ factors it has been shown, for example, that the sequence of the −10 element can define a promoter as specific for σX, σW, or both [22]. A role of the spacer region in promoter selectivity has been inferred in the case of σV [23].

Figure 1. Promoter consensus sequences for σM, σX, σW, and σV.

Promoters recognized by ECF family σ factors are characterized by conserved sequences near the −35 and −10 regions relative to the transcription start site. The consensus sequences shown here share the characteristic “AAC” motif common to many ECF family σ factors [15]. The consensus sequences shown are derived from published datasets: σM [29], σX [47], σW [26-28, 31], and σV [23]. The key role of the −10 element in discrimination of promoters by σX and σW has been previously explored by mutagenesis [22].

For several of the ECF σ factors, there is a significant basal activity even in the absence of a specific stimulus. As a result, many genes regulated by ECF σ factors could be discriminated by a large transcriptomic analysis of B. subtilis gene expression across 104 different conditions (including a variety of stresses, but none known to activate specifically ECF σ regulons) [24]. Genes associated with an ECF-type promoter (assigned as σM, σX, σW, σY or some combination) were co-clustered in terms or overall expression pattern, but the individual regulons could not be distinguished. More complete definition of each regulon has required the conditional overexpression of individual σ factors or the use of specific inducing conditions.

σW and adaptation to membrane-active agents

The σW regulon comprises ~60-90 genes, although the precise composition of the regulon depends on experimental conditions [25]. In early studies, many of the strongest σW-dependent promoters were identified by sequence similarity to the known, σW-dependent autoregulatory promoter of the sigW operon [26,27] and further members were added by monitoring σW-dependent mRNAs resulting from in vitro transcription of genomic DNA with purified σW holoenzyme [28]. Further refinements have emerged from meta-analysis (hierarchical clustering) of multiple transcriptional profiling experiments, including those conducted under various cell envelope stress conditions [29]. These studies have revealed that membrane-active compounds such as detergents are amongst the strongest inducers of the σW regulon. Other conditions known to elicit a strong, σW-dependent response include some peptidoglycan synthesis inhibitors and alkali stress [30]. Induction by alkali stress does not appear to be adaptive, suggesting that high pH may interfere with envelope integrity or function and thereby trigger the σW stress response.

The σW regulon is expressed at a low, basal level even in unstressed cells growing in rich medium at 37° C [31]. In response to stress, the regulon is activated. Mechanistically, this involves inactivation of the RsiW (regulator of sigW) anti-σ by a proteolytic cascade initiated by PrsW, which cleaves the anti-σ exterior to the membrane, followed by RasP, an intramembrane protease [16,32-35]. The precise signals that activate this protease cascade are not yet understood. One possibility is that destabilization of the membrane enhances cleavage of RsiW by PrsW.

Insights into the role of the σW in cell envelope homeostasis have emerged from characterization of the σW regulon and phenotypic characterization of mutant strains lacking either sigW or one or more target genes [25]. The characterization of the σW regulon has revealed a large number of genes encoding a variety of functions implicated in resistance to antimicrobial agents (Table 1) [27,28]. For example, σW is required for the expression of a cytosolic enzyme, FosB, that functions in the bacillithiol-dependent inactivation of fosfomycin, a small epoxide-containing antibiotic that inhibits MurA, an early cytosolic step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis [36]. It is likely that this enzyme also helps detoxify other antimicrobials containing reactive electrophilic centers as found, for example, with compounds made by B. amyloliquifaciens FZB42 [•37]. In addition, σW-dependent functions are important for resistance against nisin and related antimicrobial peptides (lantibiotics) (Table 1). Bacillus species produce many lantibiotics, and in general producer strains have specific immunity systems to protect against the lantibiotics that they produce [38]. In contrast, ECF σ regulated functions provide a more generic level of protection [39]. Nisin binds to the lipid II intermediate of peptidoglycan (PG) synthesis and induces pore formation. The σW stress response is specifically protective against lantibiotics that form pores in the membrane but contributes little to protection against a nisin variant that binds lipid II but does not form pores [39]. Protection against the membrane-destabilizing effects of nisin is due, in part, to induction of PspA, a phage-shock protein homolog that stabilizes the membrane [40], and has been proposed as a general biomarker for membrane-disrupting antimicrobials [41]. Other protective functions include YvlC (a PspC homolog), SppA (a signal-peptide peptidase that cleaves peptides inside the membrane), and the YceGHI operon [39]. σW also plays a role in protecting B. subtilis against several other antimicrobial peptides (bacteriocins) made by Bacillus sp. including sublancin (a peptide antibiotic encoded on the SPβ prophage), the cannibalism toxin SdpC, and amylocyclicin, a small hydrophobic peptide made by B. amyloquifaciens FZB42 [•37,42]. In several of these examples, the σW-dependent resistance determinants have been identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Major members of the σW, σX and σV regulons with assigned functions

| Operon1 | Other Regulators | Function |

|---|---|---|

| σW regulon | ||

| sigWrsiW | Positive autoregulation; RsiW is anti-σW factor | |

| pbpEracX | LMW PBP and amino acid racemase; PbpE (PBP4*) has PG hydrolase activity and contributes to resistance to PG inhibitors, particularly in high salt growth conditions [84] | |

| (fabHa)fabE | Alters membrane fatty acyl chain composition; Decreases fluidity and increases resistance to membrane disrupting agents [43] | |

| fosB | Fosfomycin resistance [36]; Contributes to resistance against amylocyclicin [•37,42] | |

| ydbST | Contributes to resistance against amylocyclicin [•37,42] | |

| sppA | Signal peptide peptidase; contributes to lantibiotic resistance [39] | |

| pspA | PspA (phage-shock protein) homolog; contributes to lantibiotic resistance [39] | |

| yvlABCD | YvlC=PspC homolog; contributes to lantibiotic resistance [39] | |

| yceCDEFGHI | Tellurite resistance gene homologs; contributes to lantibiotic resistance [39] | |

| yqeZfloAyqfB | FloA is a flotillin involved in regulating membrane fluidity; resistance to sublancin [42] | |

| yfhLM | resistance to SdpC* (toxic peptide) [42] | |

| yknWXYZ | resistance to SdpC* (toxic peptide) [42] | |

| yuaFfloTyuaI | FloT is a flotillin involved in regulating membrane fluidity; contributes to cefuroxime resistance [85] | |

| σX regulon | ||

| sigXrsiX | σ A | Positive autoregulation; RsiX is anti-σX factor |

| dltABCD | σ V | D-alanylation of teichoic acids; resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) [39,47] |

| pssAybfMpsd | σ A | Phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthesis; CAMP resistance [39,47] |

| pbpX | σ V | LMW PBP; PG modification, contributes to lysozyme resistance [17] |

| abh | σ V | Transition-state regulator (DNA-binding protein); increases β-lactam resistance [48] and activates expression of the glycopeptide antibiotic sublancin [49] |

| tagU | Formerly lytR; one of three redundant wall-teichoic acid attaching enzymes [69] | |

| csbByfhO | σ B | CsbB=Glucosyltransferase; involved in cell envelope polymer synthesis? [79] |

| rapD | RghR | Putative response-regulator aspartate phosphatase; negatively regulates ComA, an activator of genetic competence [86] |

| [yabE] | σ M | Negatively regulated by an ECF o activated antisense; encodes a PG hydrolase [87] |

| σV regulon | ||

| sigVrsiVoatAyrhK | Autoregulation and O-acetylation of PG (OatA); contributes to lysozyme resistance [17,23] | |

| dltABCD | σ X | resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs); lysozyme resistance [23,47] |

| pbpX | σ X | PG modification, contributes to lysozyme resistance [17] |

Parentheses indicate a promoter inside a gene; brackets indicate a gene on the opposite strand (antisense) relative to an upstream promoter

Collectively, these results suggest that σW controls genes that are activated by envelope stress and defend the cell against antibiotics and bacteriocins, particularly those with membrane-active properties. Indeed, σW also alters the membrane lipid composition by activating transcription from an intraoperonic promoter site in the fabHa-fabF fatty acid biosynthesis operon [43]. The net effect of this promoter is to upregulate FabF and downregulate FabHa, which together leads to changes in membrane lipid composition (longer fatty acyl chain length and increased proportion of straight chain fatty acids) that decrease membrane fluidity. Remarkably, strains that can still activate the σW regulon but which are altered so that the promoter inside the fabHa-fabF operon is no longer functional show an increased sensitivity to growth inhibition by a variety of other Bacillus spp. [43].

Although the precise role of many σW regulated genes remains to be elucidated, the results to date support a model in which the major role of this stress response is to defend the cell against the myriad bacteriocins and other antimicrobials present in the soil community, including many made by Bacillus spp. [38,44].

σX contributes to resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides

The σX regulon is comparatively small and overlaps extensively with those of other ECF σ factors. A sigX mutant strain is sensitive to heat and oxidative stress, but the basis of these effects is not clear [45]. In several cases, σX has an overlapping protective function with other ECF σ factors. For example, σX plays a secondary role (to σM) in resistance to β-lactam antibiotics [46], and also plays a role in protection against the lantibiotic nisin and the peptidoglycan synthesis inhibitor bacitracin (Table 1). The operons most strongly activated by σX include the dltA operon, encoding enzymes for the D-alanylation of teichoic acids, and the pssA operon, encoding enzymes for the synthesis of the phosphatidylethanolamine, a neutral lipid [47]. The common feature of these two systems is that they decrease the net negative charge of the cell envelope, and this has been suggested to account for the protective role of σX in resisting the action of cationic antimicrobial peptides [47]. The σX regulon has been found to contribute to β-lactam resistance [48] and to the synthesis of sublancin [49], and in both cases this has been linked to the induction of the regulatory protein Abh by σX (Table 1).

σV mediates resistance to lytic enzymes

The regulon controlled by σV was defined by transcriptomic analyses of strains engineered to inducibly express σV protein [23,50]. The results indicate a strong autoregulatory induction of the sigV operon together with the activation of several operons also known to be controlled by other ECF σ factors. The sigV operon itself encodes σV, the RsiV anti-σ factor, a peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase (OatA), and an uncharacterized protein (YrhK). The modification of peptidoglycan by O-acetylation is known to be associated with resistance to lytic endoglycosidases such as lysozyme [51], which motivated studies to test the role of σV in lysozyme resistance. Indeed, σV is strongly and specifically induced by lysozyme and activation confers lysozyme resistance through activation of OatA-dependent peptidoglycan modification and the Dlt system which, as noted above, modifies teichoic acids by D-alanylation [17,23]. A role for σV in lysozyme resistance has also been demonstrated in Enterococcus faecalis and Clostridium difficile [•52,53].

The induction of the σV regulon by lysozyme suggests that perhaps this system responds directly to damage to the cell wall. However, the amount of lysozyme needed to activate this system is orders of magnitude below the amount needed to lyse cells [23]. This conundrum was resolved when it emerged that the RsiV regulatory protein can bind directly to lysozyme leading to proteolytic cleavage of the anti-σ [••54]. An unidentified site protease mediates the initial cleavage of RsiV in the extracytoplasmic portion of the protein, followed by intramembrane cleavage by RasP [55]. These observations suggest that the σV stress response has evolved to detect and defend against lytic enzymes. It is known that some predatory soil bacteria deploy lysozyme-like enzymes to help lyse their prey, and this may have provided the selective pressure that led to the development of this inducible system. In human pathogens, systems orthologous to σV may now function to guard against the lytic activity of mammalian lysozymes deployed as part of the innate immune defenses.

σM and adaptation to inhibitors of peptidoglycan synthesis

The σM regulon includes at least 30 distinct promoter sites that elevate the expression of 60 or more genes [29]. In marked contrast to σW, where the majority of target genes encode proteins of rather specialized function mediating resistance to antimicrobial peptides and membrane-active compounds, the effects of σM are directed at modulating expression of the core machinery for cell wall biosynthesis and cell division. Many genes activated by σM encode functions essential for cell survival (under most growth conditions), a marked contrast with the other ECF σ regulons. Consistent with this central role, inactivation of the anti-σ factor that controls σM leads to lethality, presumably due to dysregulation of essential cell processes [56].

The central role of σM in helping maintain the integrity of the cell wall was first noted when it was found that sigM mutants display cell wall defects (distorted cell morphology and bulging from the division septum) when grown in the presence of high salt [56]. Indeed, the sigM regulon is activated by high salt, acidic pH, and heat stress. However, in light of the composition of the σM regulon, it is likely that the common feature of these diverse stresses is impairment of cell wall synthesis or function (analogous to the induction of the σW regulon by alkali stress, as noted above). A central role in coordinating cell wall biogenesis is also evident from the antibiotic sensitivity of sigM mutants which are, for example, highly sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics [46]. For reasons yet unclear, this defect can be suppressed, to a significant degree, by mutations in gdpP which encodes a hydrolase for cyclic-di-AMP, an essential second messenger implicated in cell envelope homeostasis [57].

Characterization of the σM regulon

The σM regulon has been defined by a combination of transcriptomics, promoter consensus searches, and in vitro transcription [58-61]. The most comprehensive analysis to date took advantage of the ability of the peptidoglycan synthesis inhibitor vancomycin to induce the σM regulon [29]. Comparison of the vancomycin stimulon in wild-type vs. sigM mutant cells together with hierarchical clustering of genes coordinately regulated across a spectrum of cell envelope active compounds identified those genes that form the core of the regulon. Finally, the direct targets of σM-dependent transcription were revealed by comparing the in vivo transcriptomic results with the results from in vitro transcription [29]. Promoters activated by σM can be conceptually divided into three functional classes (Table 2), together with others of still undefined function.

Table 2.

Major members of the σM regulon with assigned functions

| Operon1 | Other Regulators | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Core Cell Envelope Biogenesis Functions2 | ||

| (maf)ysxAmreBCDminCD | σ A | MreBCD function in the elongasome; MinCD regulates divisome function |

| (murG)murBdivlBylxXWsbp | σ A | MurB is essential for PG synthesis; DivIB is an essential cell division protein |

| divIC | σ A | Essential cell division protein; interacts with DivIB as part of divisome |

| recUponA | σ A | PonA=PBP1; a PBP with both transglycosylase and transpeptidase activity |

| (ydbO)[ydbP]ddlmurF | σ A | Ddl is essential D-Ala D-Ala ligase for PG synthesis, MurF is essential for PG synthesis [29] |

| rodA | σ A | Essential; component of elongasome; putative lipid flippase [29,88] |

| tarABIJKL | σX, PhoPR | Ribitol teichoic acids (in B. subtilis W23 strains) [62] |

| Stress-induced Substitute Enzymes | ||

| bcrC | σ X | A UPP phosphatase; redundant with UppP (H Zhao and JDH, unpublished); contributes to bacitracin resistance [63,64] |

| amj | Amj(YdaH); redundant with MurJ(YtgP); lipid II flippase for PG synthesis [••66] | |

| ltaSa | LtaSa(YfnI), redundant with LtaS; functions as lipoteichoic acid synthase [68,89] | |

| tagT | TagT(YwtF), redundant with TagU and TagV; required for wall teichoic acid attachment to PG [69] | |

| Regulatory Proteins | ||

| sigMyhdLK | σ A | Autoregulation; YhdL is essential due to lethal effects of unrestrained σM activity [29,56] |

| spx | σA, σW, σX, σB | Spx activates a large regulon of genes in response to disulfide stress [90] |

| ywaC | ppGpp synthase; used as a bioreporter for cell envelope stress [72,•73] | |

| (sms)disAyacLM | DisA = cyclic-di-AMP synthase; regulated by DNA damage [57] | |

| abh | σ X | Transition-state regulator (DNA-binding protein); increases β-lactam resistance [48] and activates expression of the glycopeptide antibiotic sublancin [49] |

| Other Regulon Members | ||

| yqjL | A putative hydrolase; contributes to resistance to paraquat [59] | |

| ypbG | Uncharacterized phosphoesterase; proposed as a bioreporter for PG synthesis inhibitors [91] | |

| ypuA | Unknown function protein; proposed as a bioreporter for cell envelope stress [92] | |

| ytpAB | YtpB involved in C35 terpenoid synthesis [93,94] |

Parentheses indicate a promoter inside a gene; brackets indicate a gene on the opposite strand (antisense) relative to an upstream promoter.

Bold indicates genes encoding proteins that are implicated in cell envelope synthesis and cell division.

The first class includes promoters that up-regulate the core biosynthesis pathways for assembly of the cell envelope. For example, σM activates transcription of enzymes for the synthesis of PG precursors (Ddl, MurB, MurF), for peptidoglycan assembly or modification (penicillin binding proteins PonA and PbpX), and key components of the macromolecular complexes that coordinate PG synthesis, the elongasome (MreBCD, RodA) and the divisome (DivIB, DivIC, MinCD). In B. subtilis W23 strains, wall teichoic acid (WTA) synthesis is activated directly by σM [62]. In several cases, these core biosynthetic enzymes are encoded in complex operons with multiple promoters; σM is not required for their expression but instead serves to increase expression in times of stress [29]. The selective pressures leading to inclusion of these particular enzymes in the σM regulon are not well understood. Perhaps these enzymes are rate-limiting for function, particularly in cells exposed to antimicrobial compounds and bacteriocins.

The second class of σM-dependent promoters activates genes encoding stress-induced replacement enzymes that provide a backup for key steps in cell envelope synthesis. For example, σM (together with two other stress-responsive σ factors, σX and σI) can activate expression of bcrC [63], encoding a phosphatase that converts undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate (UPP) to the monophosphate (UP), the lipid carrier for both PG and WTA synthesis [64]. BcrC is functionally redundant with another, structurally unrelated, phosphatase, UppP (H. Zhao and JDH, unpublished). By catalyzing UPP dephosphorylation on the external face of the cell membrane, BcrC rapidly converts surface exposed UPP, which is the target molecule for the antimicrobial peptide bacitracin, to UP. Interestingly, the σM regulon is also induced by friulimicin, which binds specifically to the UP lipid carrier for PG synthesis [65].

More recently, the σM activated YdaH protein was shown to be functionally redundant with a MurJ homolog and therefore renamed as an alternate to murJ (Amj) [••66]. The cell requires either MurJ or Amj for cell wall synthesis. The proposed function of MurJ/Amj is translocation of the lipid II PG precursor across the inner membrane (a function also ascribed to the RodA/FtsW family of proteins; [67]). Presumably, induction of Amj provides a mechanism for cells to continue PG synthesis even when faced with molecules that might inhibit the function of MurJ. An additional example is provided by the σM-dependent induction of LtaSa [29,60], an alternative synthase that catalyzes the elongation of lipoteichoic acid (LTA) polymers associated with the cell envelope [68]. The major synthase, LtaS, functions in unstressed cells, but can be replaced by activation of the σM-dependent paralog in times of stress. Finally, σM strongly activates TagT, one of three redundant LytR-CpsA-Psr (LCP) family enzymes that function in the final step of WTA synthesis to attach the lipid-linked precursor to PG [69]. One of the other LCP enzymes (TagU) is a member of the σX regulon [70]. These results suggest that this final extracellular step in WTA synthesis may also be targeted by antimicrobial compounds, and the induction of alternative enzymes may have emerged as a resistance mechanism.

A common feature of all four of these σM-activated enzymes (BcrC, Amj, LtaSa, and TagT) is that they are seemingly redundant in function with constitutively expressed enzymes. This leads to the general notion that antibiotic inhibition of the constitutively expressed enzymes may lead to the σM-dependent induction of substitute enzymes that may help the cell to evade antibiotic inhibition. What is not known is whether these alternate enzymes function solely to replace their constitutively expressed counterparts, or whether they have distinct or alternative activities not yet apparent. For example, the LTA polymer synthesized by LtaSa appears to differ, as observed in electrophoresis, from that made by LtaS [68] and distinct functions can also be envisioned for the LCP enzymes.

Finally, the third class of σM-activated promoters encodes proteins with regulatory roles. These include the anti-σ factor for σM, the Spx transcription factor (most closely associated with the response to disulfide stress and reactive oxygen species; [71]), synthases for nucleotide second messengers (the ppGpp synthase YwaC and the cyclic-di-AMP synthase DisA), and the transition state regulator Abh (which is also activated by other ECF σ factors). The induction of this diversity of regulatory proteins suggests that the full extent to which σM coordinates acclimation of the cell to antibiotic stress is yet to be appreciated. Of these target genes, ywaC is notable since its strong induction by σM led to its definition as biomarker for inhibition of cell wall synthesis [72], a tool subsequently used to screen for new antibiotics [•73].

Induction of the σM regulon by antibiotics and by defects in cell envelope biogenesis

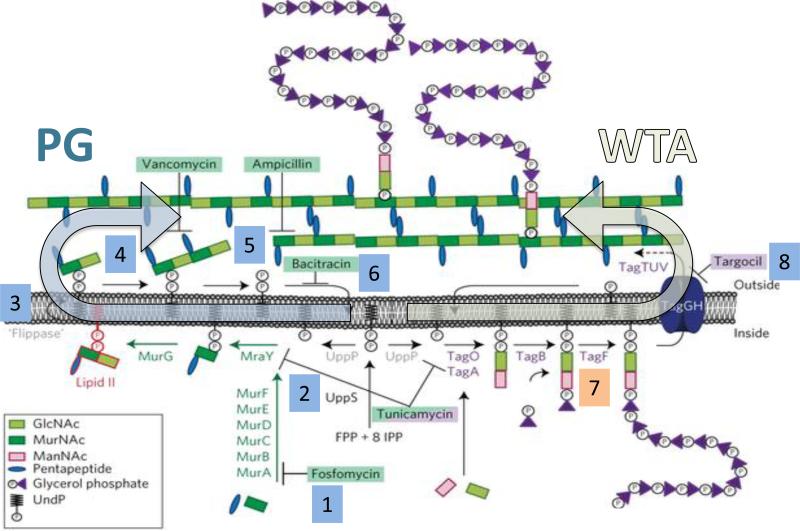

Several different cell wall active antibiotics are known to induce σM, either specifically or in combination with other cell envelope stress responses [61,74,75]. These include both early-stage (e.g. fosfomycin) and late-stage (e.g. vancomycin, moenomycin) inhibitors of PG synthesis (Figure 2). Moenomycin, which blocks the active site of the transglycosylase involved in the assembly of PG is a very specific inducer of the σM stress responses [11]. In contrast, ramoplanin, which blocks the same step but by binding the lipid II substrate, induces σM together with other envelope stress responses [76]. A comprehensive characterization of the sensitivity and response specificity of the ywaC promoter confirms the selectivity for PG synthesis inhibitors [•73]. In addition, σM is also activated by an inhibitor of WTA synthesis, targocil [•77]. Targocil is a specific inhibitor of the S. aureus TagGH efflux channel for WTA and is not normally active against B. subtilis. However, B. subtilis strains expressing the S. aureus TarGH proteins are sensitized to targocil, and inhibition activates the σM regulon. However, inhibition of TarGH is likely to also impact PG synthesis since both WTA and PG use the common carrier molecule UP, and blocking WTA synthesis is thought to titrate the limiting pools of this lipid carrier [72].

Figure 2. Schematic of the core biosynthetic pathways for PG and WTA.

PG biosynthesis and WTA synthesis require the common lipid carrier, undecaprenyl-phosphate (UP) which is synthesized as UPP by UppS. Inhibition of PG biosynthesis (left arrow), either by antibiotics or by reduced expression of key enzymes, induces the σM regulon. Steps affected include the early cytosolic steps (box 1) (e.g. MurA; inhibited by fosfomycin; [•73]), UppS (box 2) [72,78], the lipid II flippase (box 3) [••66], the extracellular transglycosylase (box 4) and transpeptidase (box 5) reactions and dephosphorylation of UPP to UP (box 6) [11,65,•73,74]. Activity of σM is induced by inhibition of WTA synthesis (right arrow), either by depletion of TagD or other late steps (box 7) [72] or by inhibition of the TarGH transporter (box 8) [•77]. Figure adapted from [•77].

Activation of the σM regulon has also been noted in strains carrying mutations that affect specific steps in cell envelope biogenesis. For example, in a selection for vancomycin resistance a mutation in the ribosome-binding site of UppS was recovered [78]. This mutation reduces the expression of the enzyme required for UPP synthesis and leads to a modest induction of the σM regulon. Up-regulation of the σM regulon was also noted in strains affected in WTA biogenesis (conditional depletion of tagD), presumably due to sequestration of UP [72]. A similar sequestration effect has been proposed to account for the up-regulation of σM by disruption of yfhO [79]. YfhO is postulated to function as a flippase for polymer synthesized (perhaps using UP as a lipid carrier) by the CsbB glycosyl-transferase (which is itself partially under σX control; [26]).

Although the spectrum of compounds and mutations that induce the σM regulon has been relatively well defined, the nature of the inducing signal is not obvious. One suggestion is that the regulator(s) controlling σM activity might respond to changes in the availability or abundance of UP or the lipid II intermediate in PG synthesis [••66]. However, this notion is challenged by that observation that impairment of LTA synthesis also activates σM. Indeed, σM is upregulated in strains lacking the major LTA elongation enzyme, LtaS (which does not use UP), enabling synthesis of the alternate enyzme LtaSa [80]. Up-regulation of σM was also noted in strains with reduced levels of UgtP, a glycosyltansferase important for synthesis of the lipid carrier of LTA [81,82], and PgsA, which synthesizes phosphatidylglycerol, the glycerol-phosphate donor required for LTA elongation [83]. These results suggest that disruption of LTA biogenesis also generates an activating signal for the σM regulon. It is presently unclear whether this signal is distinct from that produced by conditions that impair PG synthesis.

Perspective

B. subtilis is a ubiquitous soil and plant-associated bacterium that produces a variety of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites [38,44]. It shares its environment with many other soil bacteria, including actinomycetes which are also notable for the tremendous variety of antimicrobial compounds that they produce. In this chemically complex and variable environment, the ability to modulate the composition of the cell envelope in response to antimicrobial agents has no doubt proven adaptive [8]. Numerous challenges remain as we seek to understand the nature of the inducing signals that activate each ECF σ regulon and the precise ways in which regulon activation helps counter environmental threats. Future efforts will be directed towards clarifying these inducing signals and the variety of mechanisms that allow cells to acclimate to the presence of the antimicrobial compounds ubiquitous in their environment.

HIGHLIGHTS.

B. subtilis encodes seven ECF σ factors that activate envelope stress responses

σW coordinates resistance to bacteriocins and other membrane-active agents

σX contributes to cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance

σV is induced by and protects against peptidoglycan lytic enzymes

σM is strongly induced by conditions that impair peptidoglycan synthesis

σM upregulates core pathways of envelope synthesis and cell division

σM upregulates stress-inducible pathways to overcome inhibitors

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM047446).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Feklistov A, Sharon BD, Darst SA, Gross CA. Bacterial σ factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2014;68:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonetto MA, Brown KL, Rudd KE, Buttner MJ. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase σ factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7573–7577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mascher T. Signaling diversity and evolution of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staron A, Sofia HJ, Dietrich S, Ulrich LE, Liesegang H, Mascher T. The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factor protein family. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:557–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks BE, Buchanan SK. Signaling mechanisms for activation of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1930–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza BM, Castro TL, Carvalho RD, Seyffert N, Silva A, Miyoshi A, Azevedo V. σECF factors of gram-positive bacteria: a focus on Bacillus subtilis and the CMNR group. Virulence. 2014;5:587–600. doi: 10.4161/viru.29514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan S, Hutchings MI, Mascher T. Cell envelope stress response in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:107–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aminov RI. The role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2970–2988. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rietkotter E, Hoyer D, Mascher T. Bacitracin sensing in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:768–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staron A, Finkeisen DE, Mascher T. Peptide antibiotic sensing and detoxification modules of Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:515–525. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00352-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salzberg LI, Luo Y, Hachmann AB, Mascher T, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis GntR family repressor YtrA responds to cell wall antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5793–5801. doi: 10.1128/JB.05862-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asai K, Ishiwata K, Matsuzaki K, Sadaie Y. A viable Bacillus subtilis strain without functional extracytoplasmic function σ genes. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2633–2636. doi: 10.1128/JB.01859-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Y, Asai K, Sadaie Y, Helmann JD. Transcriptomic and phenotypic characterization of a Bacillus subtilis strain without extracytoplasmic function σ factors. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5736–5745. doi: 10.1128/JB.00826-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YH, Nam KH, Helmann JD. A mutation of the RNA polymerase β′ subunit (rpoC) confers cephalosporin resistance in Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:56–65. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01449-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campagne S, Allain FH, Vorholt JA. Extra Cytoplasmic Function σ factors, recent structural insights into promoter recognition and regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;30:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho TD, Ellermeier CD. Extra cytoplasmic function σ factor activation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho TD, Hastie JL, Intile PJ, Ellermeier CD. The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σV is induced by lysozyme and provides resistance to lysozyme. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:6215–6222. doi: 10.1128/JB.05467-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campagne S, Marsh ME, Capitani G, Vorholt JA, Allain FH. Structural basis for −10 promoter element melting by environmentally induced σ factors. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmann JD. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors. Adv Microb Physiol. 2002;46:47–110. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(02)46002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascher T, Hachmann AB, Helmann JD. Regulatory overlap and functional redundancy among Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function σ factors. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6919–6927. doi: 10.1128/JB.00904-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodius VA, Segall-Shapiro TH, Sharon BD, Ghodasara A, Orlova E, Tabakh H, Burkhardt DH, Clancy K, Peterson TC, Gross CA, et al. Design of orthogonal genetic switches based on a crosstalk map of σ, anti-σs, and promoters. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:702. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu J, Helmann JD. The −10 region is a key promoter specificity determinant for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function σ factors σX and σW. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1921–1927. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.1921-1927.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guariglia-Oropeza V, Helmann JD. Bacillus subtilis σV confers lysozyme resistance by activation of two cell wall modification pathways, peptidoglycan O-acetylation and D-alanylation of teichoic acids. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:6223–6232. doi: 10.1128/JB.06023-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolas P, Mader U, Dervyn E, Rochat T, Leduc A, Pigeonneau N, Bidnenko E, Marchadier E, Hoebeke M, Aymerich S, et al. Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science. 2012;335:1103–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1206848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmann JD. Deciphering a complex genetic regulatory network: the Bacillus subtilis σW protein and intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds. Sci Prog. 2006;89:243–266. doi: 10.3184/003685006783238290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang X, Fredrick KL, Helmann JD. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis σW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the σX regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3765–3770. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3765-3770.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang X, Gaballa A, Cao M, Helmann JD. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function σ factor, σW. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:361–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao M, Kobel PA, Morshedi MM, Wu MF, Paddon C, Helmann JD. Defining the Bacillus subtilis σW regulon: a comparative analysis of promoter consensus search, run-off transcription/macroarray analysis (ROMA), and transcriptional profiling approaches. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:443–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eiamphungporn W, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis σM regulon and its contribution to cell envelope stress responses. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:830–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiegert T, Homuth G, Versteeg S, Schumann W. Alkaline shock induces the Bacillus subtilis σW regulon. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:59–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zweers JC, Nicolas P, Wiegert T, van Dijl JM, Denham EL. Definition of the σW regulon of Bacillus subtilis in the absence of stress. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinrich J, Hein K, Wiegert T. Two proteolytic modules are involved in regulated intramembrane proteolysis of Bacillus subtilis RsiW. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:1412–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinrich J, Wiegert T. YpdC determines site-1 degradation in regulated intramembrane proteolysis of the RsiW anti-σ factor of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:566–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinrich J, Wiegert T. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis in the control of extracytoplasmic function σ factors. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schobel S, Zellmeier S, Schumann W, Wiegert T. The Bacillus subtilis σW anti-σ factor RsiW is degraded by intramembrane proteolysis through YluC. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1091–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao M, Bernat BA, Wang Z, Armstrong RN, Helmann JD. FosB, a cysteine-dependent fosfomycin resistance protein under the control of σW, an extracytoplasmic-function σ factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2380–2383. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.7.2380-2383.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Scholz R, Vater J, Budiharjo A, Wang Z, He Y, Dietel K, Schwecke T, Herfort S, Lasch P, Borriss R. Amylocyclicin, a novel circular bacteriocin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:1842–1852. doi: 10.1128/JB.01474-14. [The authors report the discovery of a bacteriocin that accounts for the high sensitivity of sigW mutant strains to growth inhibition by B. amyloquefaciens FZB42 [42].] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbosa J, Caetano T, Mendo S. Class I and Class II Lanthipeptides Produced by Bacillus spp. J Nat Prod. 2015 doi: 10.1021/np500424y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kingston AW, Liao X, Helmann JD. Contributions of the σW, σM and σX regulons to the lantibiotic resistome of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:502–518. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald C, Jovanovic G, Ces O, Buck M. Membrane Stored Curvature Elastic Stress Modulates Recruitment of Maintenance Proteins PspA and Vipp1. MBio. 2015:6. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01188-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wenzel M, Kohl B, Munch D, Raatschen N, Albada HB, Hamoen L, Metzler-Nolte N, Sahl HG, Bandow JE. Proteomic response of Bacillus subtilis to lantibiotics reflects differences in interaction with the cytoplasmic membrane. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5749–5757. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01380-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butcher BG, Helmann JD. Identification of Bacillus subtilis σW-dependent genes that provide intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacilli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:765–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kingston AW, Subramanian C, Rock CO, Helmann JD. A σW-dependent stress response in Bacillus subtilis that reduces membrane fluidity. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein T. Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:845–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang X, Decatur A, Sorokin A, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis σX protein is an extracytoplasmic function σ factor contributing to the survival of high temperature stress. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:2915–2921. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2915-2921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo Y, Helmann JD. Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σM in β-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83:623–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao M, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function σX factor regulates modification of the cell envelope and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1136–1146. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1136-1146.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray EJ, Stanley-Wall NR. The sensitivity of Bacillus subtilis to diverse antimicrobial compounds is influenced by Abh. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192:1059–1067. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0630-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo Y, Helmann JD. Extracytoplasmic function σ factors with overlapping promoter specificity regulate sublancin production in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4951–4958. doi: 10.1128/JB.00549-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zellmeier S, Hofmann C, Thomas S, Wiegert T, Schumann W. Identification of σV-dependent genes of Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;253:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bera A, Herbert S, Jakob A, Vollmer W, Gotz F. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:778–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52•.Ho TD, Williams KB, Chen Y, Helm RF, Popham DL, Ellermeier CD. Clostridium difficile extracytoplasmic function σ factor σV regulates lysozyme resistance and is necessary for pathogenesis in the hamster model of infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82:2345–2355. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01483-13. [The authors demonstrate the central role for σV in lysozyme resistance, as documented in B. subtilis [17,23] has direct impact on pathogenesis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le Jeune A, Torelli R, Sanguinetti M, Giard JC, Hartke A, Auffray Y, Benachour A. The extracytoplasmic function σ factor SigV plays a key role in the original model of lysozyme resistance and virulence of Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54••.Hastie JL, Williams KB, Sepulveda C, Houtman JC, Forest KT, Ellermeier CD. Evidence of a bacterial receptor for lysozyme: binding of lysozyme to the anti-σ factor RsiV controls activation of the ECF sigma factor σV. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004643. [The RsiV anti-σ factor is shown to bind directly to lysozyme as an inducing signal to activate the σV regulon.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hastie JL, Williams KB, Ellermeier CD. The activity of σV, an extracytoplasmic function σ factor of Bacillus subtilis, is controlled by regulated proteolysis of the anti-σ factor RsiV. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:3135–3144. doi: 10.1128/JB.00292-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horsburgh MJ, Moir A. σM, an ECF RNA polymerase σ factor of Bacillus subtilis 168, is essential for growth and survival in high concentrations of salt. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:41–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gundlach J, Mehne FM, Herzberg C, Kampf J, Valerius O, Kaever V, Stulke J. An Essential Poison: Synthesis and Degradation of Cyclic Di-AMP in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:3265–3274. doi: 10.1128/JB.00564-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asai K, Yamaguchi H, Kang CM, Yoshida K, Fujita Y, Sadaie Y. DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis σ factors of extracytoplasmic function family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;220:155–160. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cao M, Moore CM, Helmann JD. Bacillus subtilis paraquat resistance is directed by σM, an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor, and is conferred by YqjL and BcrC. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2948–2956. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.2948-2956.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jervis AJ, Thackray PD, Houston CW, Horsburgh MJ, Moir A. σM-responsive genes of Bacillus subtilis and their promoters. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4534–4538. doi: 10.1128/JB.00130-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thackray PD, Moir A. σM, an extracytoplasmic function σ factor of Bacillus subtilis, is activated in response to cell wall antibiotics, ethanol, heat, acid, and superoxide stress. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3491–3498. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.12.3491-3498.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Minnig K, Barblan JL, Kehl S, Moller SB, Mauel C. In Bacillus subtilis W23, the duet σXσM, two σ factors of the extracytoplasmic function subfamily, are required for septum and wall synthesis under batch culture conditions. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1435–1447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao M, Helmann JD. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis bcrC bacitracin resistance gene by two extracytoplasmic function σ factors. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6123–6129. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6123-6129.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernard R, El Ghachi M, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Chippaux M, Denizot F. BcrC from Bacillus subtilis acts as an undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase in bacitracin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28852–28857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wecke T, Zuhlke D, Mader U, Jordan S, Voigt B, Pelzer S, Labischinski H, Homuth G, Hecker M, Mascher T. Daptomycin versus Friulimicin B: in-depth profiling of Bacillus subtilis cell envelope stress responses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1619–1623. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66••.Meeske AJ, Sham LT, Kimsey H, Koo BM, Gross CA, Bernhardt TG, Rudner DZ. MurJ and a novel lipid II flippase are required for cell wall biogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:6437–6442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504967112. [An elegant study that reveals that MurJ and the σM-regulated Amj are co-essential for growth and are required for PG synthesis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohammadi T, Sijbrandi R, Lutters M, Verheul J, Martin NI, den Blaauwen T, de Kruijff B, Breukink E. Specificity of the transport of lipid II by FtsW in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14707–14718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wormann ME, Corrigan RM, Simpson PJ, Matthews SJ, Grundling A. Enzymatic activities and functional interdependencies of Bacillus subtilis lipoteichoic acid synthesis enzymes. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:566–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawai Y, Marles-Wright J, Cleverley RM, Emmins R, Ishikawa S, Kuwano M, Heinz N, Bui NK, Hoyland CN, Ogasawara N, et al. A widespread family of bacterial cell wall assembly proteins. EMBO J. 2011;30:4931–4941. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang X, Helmann JD. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis σX factor using a consensus-directed search. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:165–173. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zuber P. Management of oxidative stress in Bacillus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:575–597. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.D'Elia MA, Millar KE, Bhavsar AP, Tomljenovic AM, Hutter B, Schaab C, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Brown ED. Probing teichoic acid genetics with bioactive molecules reveals new interactions among diverse processes in bacterial cell wall biogenesis. Chem Biol. 2009;16:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73•.Czarny TL, Perri AL, French S, Brown ED. Discovery of novel cell wall-active compounds using P ywaC, a sensitive reporter of cell wall stress, in the model gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3261–3269. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02352-14. [A detailed characterization of the response of the σM-regulated ywaC gene to a variety of cell envelope active antibiotics and demonstration of the utility of this system for drug discovery.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cao M, Wang T, Ye R, Helmann JD. Antibiotics that inhibit cell wall biosynthesis induce expression of the Bacillus subtilis σW and σM regulons. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1267–1276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mascher T, Margulis NG, Wang T, Ye RW, Helmann JD. Cell wall stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: the regulatory network of the bacitracin stimulon. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1591–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wecke T, Bauer T, Harth H, Mader U, Mascher T. The rhamnolipid stress response of Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;323:113–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77•.Schirner K, Eun YJ, Dion M, Luo Y, Helmann JD, Garner EC, Walker S. Lipid-linked cell wall precursors regulate membrane association of bacterial actin MreB. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:38–45. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1689. [Documents the effects of the recently developed antibacterial compound targocil, an inhibitor of the TarGH exporter of WTA, on cell physiology including dissociation of MreB from the membrane and induction of the σM stress response.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee YH, Helmann JD. Reducing the Level of Undecaprenyl Pyrophosphate Synthase Has Complex Effects on Susceptibility to Cell Wall Antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00794-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Inoue H, Suzuki D, Asai K. A putative bactoprenol glycosyltransferase, CsbB, in Bacillus subtilis activates σM in the absence of co-transcribed YfhO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;436:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hashimoto M, Seki T, Matsuoka S, Hara H, Asai K, Sadaie Y, Matsumoto K. Induction of extracytoplasmic function σ factors in Bacillus subtilis cells with defects in lipoteichoic acid synthesis. Microbiology. 2013;159:23–35. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.063420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matsuoka S, Chiba M, Tanimura Y, Hashimoto M, Hara H, Matsumoto K. Abnormal morphology of Bacillus subtilis ugtP mutant cells lacking glucolipids. Genes Genet Syst. 2011;86:295–304. doi: 10.1266/ggs.86.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salzberg LI, Helmann JD. Phenotypic and transcriptomic characterization of Bacillus subtilis mutants with grossly altered membrane composition. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7797–7807. doi: 10.1128/JB.00720-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hashimoto M, Takahashi H, Hara Y, Hara H, Asai K, Sadaie Y, Matsumoto K. Induction of extracytoplasmic function σ factors in Bacillus subtilis cells with membranes of reduced phosphatidylglycerol content. Genes Genet Syst. 2009;84:191–198. doi: 10.1266/ggs.84.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palomino MM, Sanchez-Rivas C, Ruzal SM. High salt stress in Bacillus subtilis: involvement of PBP4* as a peptidoglycan hydrolase. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee YH, Kingston AW, Helmann JD. Glutamate dehydrogenase affects resistance to cell wall antibiotics in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:993–1001. doi: 10.1128/JB.06547-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogura M, Fujita Y. Bacillus subtilis rapD, a direct target of transcription repression by RghR, negatively regulates srfA expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;268:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eiamphungporn W, Helmann JD. Extracytoplasmic function σ factors regulate expression of the Bacillus subtilis yabE gene via a cis-acting antisense RNA. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1101–1105. doi: 10.1128/JB.01530-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henriques AO, Glaser P, Piggot PJ, Moran CP., Jr. Control of cell shape and elongation by the rodA gene in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:235–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schirner K, Marles-Wright J, Lewis RJ, Errington J. Distinct and essential morphogenic functions for wall- and lipo-teichoic acids in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 2009;28:830–842. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rochat T, Nicolas P, Delumeau O, Rabatinova A, Korelusova J, Leduc A, Bessieres P, Dervyn E, Krasny L, Noirot P. Genome-wide identification of genes directly regulated by the pleiotropic transcription factor Spx in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9571–9583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hutter B, Fischer C, Jacobi A, Schaab C, Loferer H. Panel of Bacillus subtilis reporter strains indicative of various modes of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2588–2594. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2588-2594.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Urban A, Eckermann S, Fast B, Metzger S, Gehling M, Ziegelbauer K, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Freiberg C. Novel whole-cell antibiotic biosensors for compound discovery. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6436–6443. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00586-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kingston AW, Zhao H, Cook GM, Helmann JD. Accumulation of heptaprenyl diphosphate sensitizes Bacillus subtilis to bacitracin: implications for the mechanism of resistance mediated by the BceAB transporter. Mol Microbiol. 2014;93:37–49. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sato T, Yoshida S, Hoshino H, Tanno M, Nakajima M, Hoshino T. Sesquarterpenes (C35 terpenes) biosynthesized via the cyclization of a linear C35 isoprenoid by a tetraprenyl-β-curcumene synthase and a tetraprenyl-β-curcumene cyclase: identification of a new terpene cyclase. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9734–9737. doi: 10.1021/ja203779h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]