Abstract

One of the major challenges in structural characterization of oligosaccharides is the presence of many structural isomers in most naturally-occurring glycan mixtures. Although ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) has shown great promise in glycan isomer separation, conventional IMS separation occurs on the millisecond time scale, largely restricting its implementation to fast TOF analyzers which often lack the capability to perform electron activated dissociation (ExD) tandem MS analysis and the resolving power needed to resolve isobaric fragments. The recent development of trapped ion mobility spectrometry (TIMS) provides a promising new tool that offers high mobility resolution and compatibility with high-performance Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) mass spectrometers when operated under the selected accumulation-TIMS (SA-TIMS) mode. Here, we present our initial results on the application of SA-TIMS-ExD-FTICR MS to the separation and identification of glycan linkage isomers.

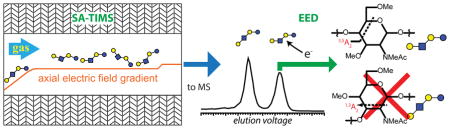

Graphical Abstract

Glycans are ubiquitously present in all eukaryotic cells, participating in a wide range of cellular processes.1 Unlike the assembly of proteins or DNA, glycan biosynthesis is not template-driven, but rather the concerted action of glycan processing enzymes, with its outcome modulated by the local enzyme expression and the monosaccharide nucleotide donor levels. Consequently, a glycome often comprises a repertoire of closely-related structures, many of which are structural isomers. This, together with the complexity of glycan structures and the lack of a glycan amplification mechanism, presents a severe analytical challenge to the field of glycomics.

Mass spectrometry (MS) has recently emerged as an indispensable tool for structural glycomics.2–3 As a detection method, MS offers unmatched specificity over alternatives such as pulsed-amperometric detection and laser-induced fluorescence. Further, detailed glycan structural information can be obtained by tandem MS (MS/MS) analysis employing a variety of fragmentation methods. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) can generate an abundance of glycosidic fragments which are key to the elucidation of the glycan sequence and branching pattern.4–6 Linkage configuration can be inferred from cross-ring fragments which are more readily produced by electron activated dissociation (ExD) methods,7–11 including electron capture dissociation (ECD), electron transfer dissociation (ETD), electronic excitation dissociation (EED) and electron detachment dissociation (EDD), or by sequential tandem MS (MSn).12 Permethylation is a common sample preparation step which improves the glycan ionization efficiency and increases their thermal stability.13 It also facilitates differentiation of internal and terminal fragments, an important task in de novo glycan sequencing. Metal adduction is often used to promote cross-ring cleavages and to minimize proton-induced rearrangements.14

Because of the presence of isomeric glycans, fractionation prior to MS analysis is often needed for characterization of complex glycan mixtures. Capillary electrophoresis (CE) is a powerful tool for glycan separation owing to its high sensitivity and speed, as well as its superior peak capacity and isomer resolution. However, online CE-MS of glycans remains challenging as the buffer additives used for optimal CE separation often lead to reduced MS performance.15–16 Various liquid chromatography (LC) methods have been developed for glycan separation. These include high-pH anion exchange chromatography, hydrophilic interaction LC, reversed-phase LC (RP-LC), and LC employing graphitized carbon column (GCC).17–22 With the exception of RP-LC, these LC methods achieve their best performance on native or reducing-end derivatized glycans. Among them, GCC offers the best isomer separation power, but its chromatographic resolution is significantly reduced for permethylated glycans. Further, efficient post-column metal-adduction is difficult, particularly in nano-LC systems, thus limiting on-line LC-MS analysis to protonated species, or ammonium and, occasionally, sodium adducts.22

Unlike CE or LC, ion mobility spectrometry (IMS)23–24 is a post-ionization, gas-phase separation method. As such, it permits easy introduction of metal cations, works with both native and permethylated glycans, and provides orthogonal analyte separation following LC fractionation.25 In conventional drift-tube (DT)-IMS,24,26 ions are separated based on their mobility through a gas-filled tube, driven by an electric field. The measured mobility of an ion can be used to calculate its collisional cross section (CCS) which may be compared to the CCS values of standards or from theoretical modeling to aid in analyte identification.27 Similar mobility-based separation has also been achieved in travelling wave IMS (TWIMS).28 In DT-IMS and TWIMS, ion separation occurs on the millisecond time scale, and this has largely restricted their implementation to instruments with fast mass analyzers, typically time-of-flight (TOF) instruments.

Successful IMS coupling to slow mass analyzers requires selective transfer/accumulation of ions of a specific mobility. This can be achieved by employing dual gate ion filtration.29–31 Alternatively, mobility selection can be realized by spatial ion dispersion. In field asymmetric-waveform IMS (FAIMS) or differential mobility spectrometry (DMS),25,32–34 ions are displaced laterally based on their differential mobilities in high- and low-electric fields as they move into a mobility region in the presence of an asymmetric alternating potential perpendicular to the direction of the ion motion. A DC potential can be used to compensate the lateral ion drift, allowing continuous passage of ions with a given differential mobility. The analytical potential of FAIMS coupled to slower scanning but high-performance mass spectrometers, such as the Orbitrap and the Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) instruments was recently demonstrated.25,34 Despite its promise, FAIMS has limited peak capacity, and does not provide ion CCS values.

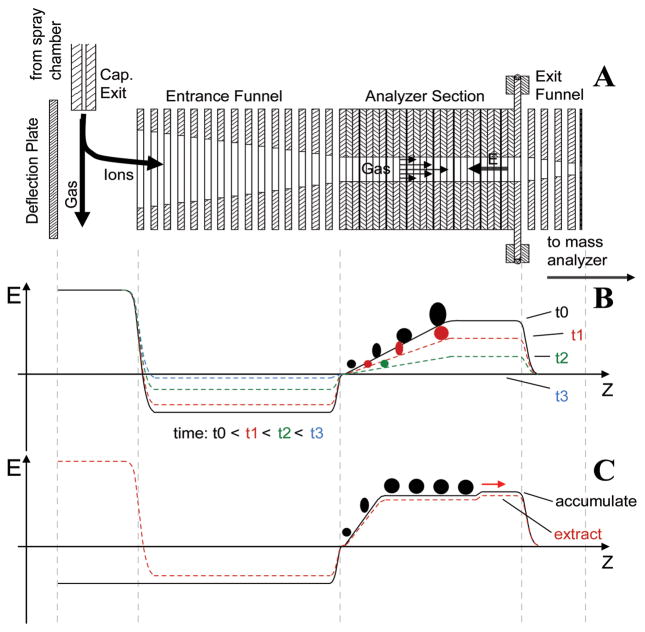

The recently developed trapped IMS (TIMS)35–37 offers a means to achieve high-resolution, mobility-based, axial ion separation. Figure 1a shows the schematic of a TIMS funnel, with its operating principle illustrated in Figure 1b. In TIMS, ions are pushed forward by a carrier gas through the analyzer section in the presence of an axially variable, retarding electric field. An ion with a mobility of K is trapped in a region where the electric field strength, E, is such that the ion drift velocity (KE) equals the carrier gas flow velocity,

Figure 1.

a) Schematic of a TIMS funnel. b) The operating principle of TIMS. c) The operating principle of SA-TIMS.

| (Eq. 1) |

Following the ion trapping event, E is gradually reduced by decreasing the analytical ramp voltage, ΔV, defined as the potential difference between the exit and entrance lenses of the analyzer, and this results in sequential elution of trapped ions, from low-mobility to high-mobility species. In principle, the ramping rate of ΔV can be adjusted to allow the study of TIMS-separated ions by slow analysis methods. In practice, however, because ions of a given mobility are trapped only in a narrow section of the TIMS analyzer, their abundance is generally insufficient for analysis methods that demand a high precursor ion count, such as ExD and MSn.

The voltage divider within the TIMS analyzer can be reconfigured to create an axial potential that varies linearly over its center section. The resulting electric field along the ion path (Figure 1c) contains a plateau, where selective trapping of ions with the desired mobility occurs. Ions with higher mobility are blocked by the steep ramp near the analyzer entrance, and ions with lower mobility are not retained by the small barrier near the analyzer exit. At the end of the ion accumulation event, the polarity of the deflector potential is switched to the opposite of the ion polarity to stop ion transmission into the TIMS funnel. A brief storage period follows to ensure elimination of ions with incorrect mobilities, before ΔV is reduced for ion extraction. In this mode of operation known as the selected accumulation-TIMS (SA-TIMS),38 or simply SAIMS,39 a much larger volume of the mobility analyzer is utilized for storage of ions with the desired mobility, thus overcoming the space charge limit encountered in the TIMS operating mode. An IM spectrum is produced by scanning ΔV. For a given bath gas pressure, the mobility resolution of SA-TIMS is determined by the barrier height near the analyzer exit, provided that sufficient data points are acquired within each mobility peak. The analytical power of SA-TIMS-coupled FTICR MS analysis was recently demonstrated by Fernadez-Lima et al. for direct separation and characterization of targeted compounds from complex mixtures.38

IMS-MS analysis of isomeric glycans has been reported by a number of groups.29,34,40–48 The majority of these studies relied on DT-IMS or TWIMS separation and employed TOF analyzers, with CID as the fragmentation method for tandem MS analysis. However, a recent study highlighted the need for using alternative fragmentation methods, such as vacuum ultraviolet photodissociation, for identification of IMS-separated glycans, as CID failed to sufficiently distinguish between glycan isomers.45 In another study, Amster et al. showed that even epimeric glycan isomers can be separated by FAIMS and subsequently differentiated by EDD-FTICR MS analysis.34

In this study, we explored the analytical potential of combining SA-TIMS separation with ExD-FTICR MS for characterization of isomeric glycan mixtures, and compared its performance to the DT-IMS-CID-TOF MS method. All mass spectra were acquired on either a 12-T solariX™ hybrid Qh-FTICR mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a TIMS device, or a 6560 DT-IMS-Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The relevant SA-TIMS operating parameters are given in the figure captions, and detailed in the supporting information. Conditions of tandem MS analyses are described in the supporting information.

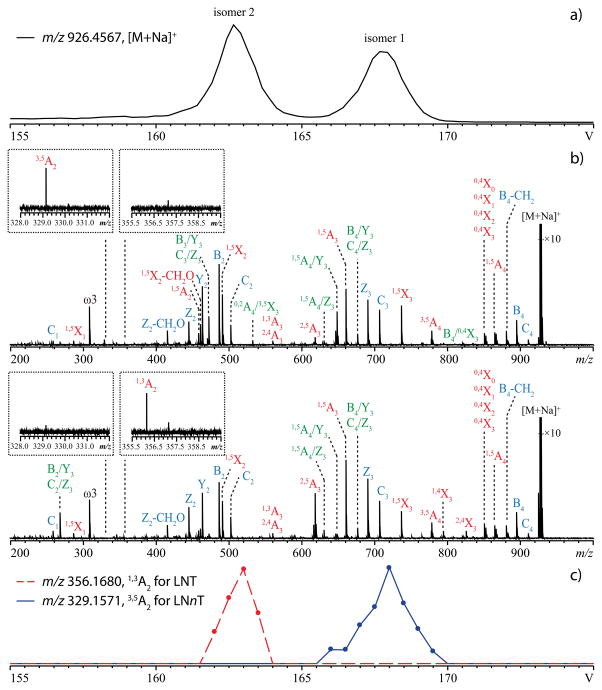

When a mixture of the permethylated tetrasaccharides lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) was infused into the SA-TIMS-FTICR mass spectrometer, a survey scan of ΔV produced an extracted ion mobiligram (EIM) of the singly sodiated species, [M + Na]+, at m/z 926.4567, with two baseline-resolved peaks (Figure 2a) (R = 77), indicating successful separation of these two isomers by SA-TIMS.

Figure 2.

a) EIM ([M + Na]+, m/z 926.4567) of a mixture of permethylated LNT and LNnT. ΔV was scanned from 175 V to 145 V over 120 steps. b) EED spectra of the SA-TIMS-isolated isomer 1 (top) and isomer 2 (bottom). The insets show zoomed-in views of diagnostic peaks (1,3A2 ion for LNT and 3,5A2 ion for LNnT). ΔV was fixed at 168.0 V for isomer 1 and at 162.5 V for isomer 2. c) EIMs of the diagnostic fragment ions during a SA-TIMS-EED MS/MS analysis. ΔV was scanned from 175 V to 155 V over 40 steps. For all analyses, the gas pressure inside the TIMS funnel was 2.52 mBar.

LNT and LNnT are structural isomers which differ only by the linkage between the non-reducing end galactose (Gal) and N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) residues (1→3 for LNT and 1→4 for LNnT, Scheme S1). They may be differentiated by tandem mass spectrometry based on their respective linkage-specific cross-ring fragments: 1,3A2 or 1,3X2 for LNT, and 3,5A2 or 3,5X2 for LNnT. Previous studies showed that these diagnostic fragments were not observed in their CID, ECD, or ETD spectra, but can be produced by EED.10–11 Here, the analytical ramp voltage was adjusted to allow selective accumulation and elution of each isomer for EED tandem MS analysis. Despite the similarity in the EED spectra of LNT and LNnT (Figure 2b), each spectrum contains a cross-ring fragment unique to one of the isomers (Figure 2b, insets), thus allowing unambiguous identification of isomer 1 as LNnT and isomer 2 as LNT (the detailed lists of fragments can be found in Tables S1, S2). Tandem MS analysis can also be carried out while ΔV is varied over time. Although such an IMS-MS/MS experiment is analogous to an LC-MS/MS run, the SA-TIMS scan rate and range can be easily adjusted to allow acquisition of many tandem mass spectra of a targeted species to improve the S/N ratio, whereas the number of signal averaging is limited by the peak width of each eluted species in LC-MS/MS runs. Figure 2c shows the EIMs of the diagnostic fragment ions from a SA-TIMS-EED-MS/MS experiment. The peak positions in the EIMs of 1,3A2 ion (m/z 356.1680) and 3,5A2 ion (m/z 329.1571) coincide with those of the isomer 2 and isomer 1 parent ions, respectively (Figure 2a), further confirming the assignment.

In a SA-TIMS experiment, the electric field strength, E, at the plateau where ion trapping occurs, is inversely proportional to the mobility of the trapped ions, K, (Eq. 1), or their reduced mobility, K0, defined as:

| (Eq. 2) |

where P is the drift gas pressure in Torr, and T is the drift gas temperature in Kelvin. Since E scales with ΔV, K0 should scale with 1/ΔV. Thus, a calibration curve can be constructed by measuring ΔV of ions with known K0 at their time of elution, and used to obtain Ko of an unknown from its measured ΔV value. The CCS of an ion, Ω, can then be calculated in a straightforward way based on its Ko and other instrument parameters:

| (Eq. 3) |

where Q is the ion charge, N0 is the neutral number density at standard temperature and pressure, μ is the reduced mass of the ion and the drift gas molecule, and kb is the Boltzmann constant.

Here, mobility calibration was performed manually using the Agilent Tunemix. The EIMs of several calibrants and the calibration plot are shown in Figure S1. The calculated CCS values of the singly sodiated permethylated LNT and LNnT are 290.6 Å2 and 300.0 Å2, respectively. These values are consistent with those measured by DT-IMS (Table S3). With the DT-IMS, permethylated LNT and LNnT were only partially resolved due to its lower mobility resolving power (Figure S2). Although EED is not available on the DT-IMS-Q-TOF instrument, CID can be used to differentiate these two linkage isomers based on the facile loss of the C3-substituent from the 1→3 linked GlcNAc in LNT (Figures S3 and S4).49 However, glycan linkage isomers do not always produce signature glycosidic fragments under CID, and linkage determination often relies on specific cross-ring fragments which can be produced by ExD or MSn, making SA-TIMS an attractive online separation method due to its compatibility with these slower analysis methods.

In summary, the coupling of SA-TIMS to FTICR MS provides an analytical platform for generating IMS-mass spectra with high mobility, high mass resolution, and high mass accuracy as well as the ability to perform ExD tandem MS analysis on mobility-selected ions for confident analyte identification. The ion CCS values obtained by SA-TIMS agree well with those measured by the conventional DT-IMS. The SA-TIMS-ExD-FTICR MS approach shows great promise in the separation and identification of isomeric glycans, and should also find ample applications in the characterization of other classes of biomolecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from NIH grants P41 RR010888/GM104603 and S10 RR025082.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Experimental details, additional schemes, figures and tables as noted in the text.

References

- 1.Varki A. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaia J. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2004;23:161–277. doi: 10.1002/mas.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kailemia MJ, Ruhaak LR, Lebrilla CB, Amster IJ. Anal Chem. 2013;86:196–212. doi: 10.1021/ac403969n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhold VN, Reinhold BB, Costello CE. Anal Chem. 1995;67:1772–1784. doi: 10.1021/ac00107a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viseux N, deHoffmann E, Domon B. Anal Chem. 1997;69:3193–3198. doi: 10.1021/ac961285u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey DJ. J Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:1178–1190. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200010)35:10<1178::AID-JMS46>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakansson K. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2901–2910. doi: 10.1021/ac0621423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff JJ, Amster IJ, Chi L, Linhardt RJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao C, Xie B, Chan SY, Costello CE, O’Connor PB. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han L, Costello CE. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:997–1013. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0117-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu X, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Huang Y, Costello CE, Lin C. Anal Chem. 2013;85:10017–10021. doi: 10.1021/ac402886q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashline D, Singh S, Hanneman A, Reinhold V. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6250–6262. doi: 10.1021/ac050724z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciucanu I, Costello CE. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:16213–16219. doi: 10.1021/ja035660t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brüll LP, Kovácik V, Thomas-Oates JE, Heerma W, Haverkamp J. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1998;12:1520–1532. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19981030)12:20<1520::AID-RCM336>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campa C, Coslovi A, Flamigni A, Rossi M. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2027–2050. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mechref Y, Novotny MV. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28:207–222. doi: 10.1002/mas.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delaney J, Vouros P. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:325–334. doi: 10.1002/rcm.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruggink C, Maurer R, Herrmann H, Cavalli S, Hoefler F. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1085:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wuhrer M, Deelder AM, Hokke CH. J Chromatogr B. 2005;825:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ninonuevo M, An H, Yin H, Killeen K, Grimm R, Ward R, German B, Lebrilla C. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:3641–3649. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costello CE, Contado-Miller JM, Cipollo JF. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1799–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, Mechref Y. Electrophoresis. 2012;33:1768–1777. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohrer BC, Merenbloom SI, Koeniger SL, Hilderbrand AE, Clemmer DE. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2008;1:293–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanu AB, Dwivedi P, Tam M, Matz L, Hill HH. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:1–22. doi: 10.1002/jms.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creese AJ, Cooper HJ. Anal Chem. 2012;84:2597–2601. doi: 10.1021/ac203321y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoaglund CS, Valentine SJ, Sporleder CR, Reilly JP, Clemmer DE. Anal Chem. 1998;70:2236–2242. doi: 10.1021/ac980059c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyttenbach T, von Helden G, Bowers MT. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8355–8364. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giles K, Pringle SD, Worthington KR, Little D, Wildgoose JL, Bateman RH. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2401–2414. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zucker SM, Lee S, Webber N, Valentine SJ, Reilly JP, Clemmer DE. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1477–1485. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clowers BH, Hill HH. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5877–5885. doi: 10.1021/ac050700s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang X, Bruce JE, Hill HH. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1115–1122. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guevremont R. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1058:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolakowski BM, Mester Z. Analyst. 2007;132:842–864. doi: 10.1039/b706039d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kailemia MJ, Park M, Kaplan DA, Venot A, Boons GJ, Li L, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;25:258–268. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0771-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernandez-Lima F, Kaplan DA, Suetering J, Park MA. Int J Ion Mobil Spec. 2011;14:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s12127-011-0067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Lima FA, Kaplan DA, Park MA. Rev Sci Instrum. 2011;82:1261061–1261063. doi: 10.1063/1.3665933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michelmann K, Silveira JA, Ridgeway ME, Park MA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:14–24. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benigni P, Thompson CJ, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Anal Chem. 2015;87:4321–4325. doi: 10.1021/ac504866v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park MA, Kaplan DA, Easterling M, Ridgeway M. Proceedings of the 61st American Society for Mass Spectrometry Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; Minneapolis, MN. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabryelski W, Froese KL. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:265–277. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clowers BH, Dwivedi P, Steiner WE, Hill HH, Jr, Bendiak B. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plasencia MD, Isailovic D, Merenbloom SI, Mechref Y, Clemmer DE. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:1706–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams JP, Grabenauer M, Holland RJ, Carpenter CJ, Wormald MR, Giles K, Harvey DJ, Bateman RH, Scrivens JH, Bowers MT. Int J Mass spectrom. 2010;298:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenn LS, McLean JA. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:2196–2205. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01414a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee S, Valentine SJ, Reilly JP, Clemmer DE. Int J Mass spectrom. 2012;309:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Giles K, Bendiak B, Kaplan K, Siems WF, Hill HH., Jr Anal Chem. 2012;84:3231–3239. doi: 10.1021/ac203116a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Bendiak B, Siems WF, Gang DR, Hill HH., Jr Anal Chem. 2013;85:2760–2769. doi: 10.1021/ac303273z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Both P, Green AP, Gray CJ, Šardzík R, Voglmeir J, Fontana C, Austeri M, Rejzek M, Richardson D, Field RA, Widmalm G, Flitsch SL, Eyers CE. Nat Chem. 2014;6:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morelle W, Faid V, Michalski JC. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2451–2464. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.