Abstract

Background

In the health reform era, rehospitalization following discharge may result in financial penalties to hospitals. The effect of increased hospital-skilled nursing facility (SNF) linkage on readmission reduction following surgery has not been explored.

Methods

To determine whether enhanced hospital-SNF linkage, as measured by the proportion of surgical patients referred from a hospital to a particular SNF, would result in reduced 30-day readmission rates for surgical patients, we used national Medicare data (2011-12) and evaluated patients who received one of five surgical procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting, hip fracture repair, total hip arthroplasty, colectomy, lumbar spine surgery). Initial evaluation was performed using regression modeling. Patient choice in SNF referral was adjusted for using instrumental variable (IV) analysis with distance between an individuals’ home and the SNF as the IV.

Results

A strong negative correlation (p<0.001) was observed between the proportion of selected surgical discharges received by a SNF and the rate of hospital readmission. Increasing the proportion of surgical discharges decreased the likelihood of rehospitalization (RC −0.04, 95% CI [−0.07, −0.02]). These findings were preserved in IV analysis. Increasing hospital-SNF linkage was found to significantly reduce the likelihood of readmission for patients receiving lumbar spine surgery, CABG and hip fracture repair.

Conclusions

The benefits of increased hospital-SNF linkage appear to include meaningful reductions in hospital readmission following surgery. Overall, a 10% increase in the proportion of surgical referrals to a particular SNF is estimated to reduce readmissions by 4%. This may impact hospital-SNF networks participating in risk-based reimbursement models.

Introduction

Recent provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) not only penalize hospitals for unplanned readmissions among Medicare patients but also incentivize improved post-acute care coordination through bundled payment programs and the creation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs).1-5 The intent of these initiatives is to streamline continuity of care, reduce rehospitalizations and enhance patient-centered outcomes that may lead to shared savings for hospitals and skilled nursing facilities participating in risk-based reimbursement models.1,4,5

Although it is acknowledged that hospitals are attempting to redesign care within their walls, less is known about the nature of their relationships with external providers who nevertheless affect performance on bundled metrics.4,5,6 Rahman and colleagues reported that hospitals with stronger skilled nursing facility (SNF) linkages, as defined by more concentrated referral patterns, reduced 30-day readmission rates for Medicare patients.6 Specifically, a 10% increase in the proportion of discharges from a hospital to a particular SNF was estimated to result in a 1.2 percentage point reduction in 30-day readmissions. It is not known, however, whether such findings apply to individuals discharged to SNFs following surgical procedures. Given the complexity of post-acute care for many surgical patients, as well as higher risks of peri-operative morbidity1,2,7, it is possible that hospital-SNF linkage may have a more dramatic effect on readmission reduction among Medicare beneficiaries receiving surgery.1

In this context, we sought to evaluate the effect of hospital-SNF linkage on 30-day rehospitalization among a sample of Medicare patients discharged to SNFs who had received one of five common inpatient surgical procedures. We hypothesized that enhanced hospital-SNF linkage, as measured by the proportion of surgical patients referred from a hospital to a particular SNF, would result in reduced 30-day readmission rates.

Methods

Participants and Databases

Data for these analyses come from 100% Medicare Part A claims (for hospital and SNF care) and Medicare enrollment data for the years 2011-12. Additionally, we used 2011 On-line Survey & Certification Automated Record (OSCAR) data to capture SNF characteristics, the 2007 American Hospital Association (AHA) Survey data for hospital characteristics and the 2010 zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) file for zip code location.

Using Part A claims data, we identified all Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries who were discharged directly from an acute general hospital to a SNF for post-acute care between January 1, 2011 and November 30, 2012. We excluded any individual with a SNF stay in the one year period prior to their index hospitalization. We excluded patients with prior SNF use because prior nursing home residence would systematically affect SNF choice. We also excluded those who were treated in hospitals that had fewer than 15 surgical discharges to SNFs over the two year study period. Our final sample consisted of approximately 1.5 million Medicare FFS beneficiaries discharged from 1,964 hospitals to 12,112 SNFs. Among this pool of patients, we then identified those who received one of five common surgical interventions over the course of the two year period using ICD-9 procedure codes (available from the authors upon request). The selected procedures included coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), total hip arthroplasty, hip fracture repair, colectomy and lumbar spine surgery. These procedures were selected as they are representative of major surgical interventions performed across general surgery, orthopaedic and neurosurgical disciplines, include urgent and elective interventions and have been used in prior research to evaluate health system surgical performance.2,5,7

Primary Outcomes

Our main outcome variable was 30-day hospital readmission, defined as rehospitalization to any acute care hospital within 30-days of the date of discharge from the index surgical hospital stay.

Main explanatory variable

The main explanatory variable was hospital-SNF referral linkage, defined as the proportion of surgical patients from the originating hospital who were discharged to the treating SNF 6.

Covariates

Patient characteristics included age, gender, race, comorbidity scores (calculated using Elixhauser8 and Deyo-modified Charlson9 scales), hospital length-of-stay and intensive care unit (ICU) use. SNF attributes from the OSCAR data included the full-time equivalents (FTEs) of different types of nursing staff [registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and certified nursing assistants (CNAs)] 10-13, the proportion of Medicaid paid residents 14-17, the weighted deficiency score based on state’s inspection of the SNF13,18,19, occupancy rate, chain membership, corporate ownership (for profit or not), and the presence of any physician extenders (e.g. nurse practitioners, physician assistants, etc)20. Additionally, we included several facility level characteristics from the MDS (available at www.ltcfocus.org), including the proportion of black residents, the proportion of residents enrolled in managed care and the Resource Utilization Groups (RUGs) III case mix index (CMI).

We included two distance variables: distance from the patient’s residential zip code to SNFs and distance from the discharging hospital to SNFs. We geocoded all the SNFs and hospitals using the address in the OSCAR and AHA files, respectively. We used zip code centroids as a proxy for individuals’ residential location. We calculated patient to SNF distances using the Haversine formula21.

Statistical Analyses

Our object was to estimate the effect of increasing the proportion of selected surgical patients discharged from hospital h to SNF n on readmissions (Rihn), while adjusting for confounders including patient choice in selecting the SNF to which they were referred following surgery. The following equation was used in performing these calculations:

Prophn was our main explanatory variable, the proportion of surgical patients from hospital h discharged to SNF n. Xi is a vector of patient’s characteristics, and Xn is a vector of SNF characteristics. μh represents the hospital fixed effect. Given the large number of observations and the inclusion of a numerous covariates, we estimated a linear probability model even though the outcome was dichotomous. Based on prior research, age, gender, race, Elixhauser and Deyo-modified Charlson co-morbidity scores2,3,5,6, hospital length-of-stay and ICU use3,6, RN, LPN and CNA FTEs 10-13, the proportion of Medicaid paid residents 14-17, the weighted deficiency score based on state’s inspection of the SNF13,18,19, occupancy rate, chain membership, corporate ownership, and the presence of any physician extenders were included as co-variates in the multivariable regression model.

In order to account for factors that would influence patient decision making around the SNF they were referred to, we estimated a SNF choice model for surgical patients that predicted the likelihood of a patient going to each SNF available. The choice set was defined based on three groups of SNFs: all SNFs within a 22km radius of the discharging hospital, the nearest 15 SNFs to the hospital and all SNFs used by the hospital. Using a conditional (fixed effects) logit model, we estimated the parameters for surgical patients6,22,23 Using the choice model estimated above, we predicted the hospital-SNF discharge proportion as if the distance between an individual’s home and the alternative SNFs were the only deciding factor. The corresponding predicted proportion was then used as an instrumental variable (IV) to further adjust the results of our primary analysis. IV analysis has been widely used in the past and is maintained to imitate random assignment in its approach.1,24 Further, the use of IV analysis enables the generation of conservative and unbiased estimates, minimizing the potential for type I error. Finally, subset analyses were performed using each surgical procedure individually. The results of the linear probability model were considered primary, with the results of the IV test used as a confirmatory analysis. Supplemental sensitivity tests were conducted where inclusion was limited to hospitals with 25 or more surgical cases and where subset analyses were performed among institutions with and without inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Statistical significance was set, a-priori, for p-values <0.05 and regression co-efficients (RC) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) exclusive of 0.0.

This investigation received institutional ethical review board approval prior to commencement. This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health # P01AG027296 (PI: Vincent Mor).

Results

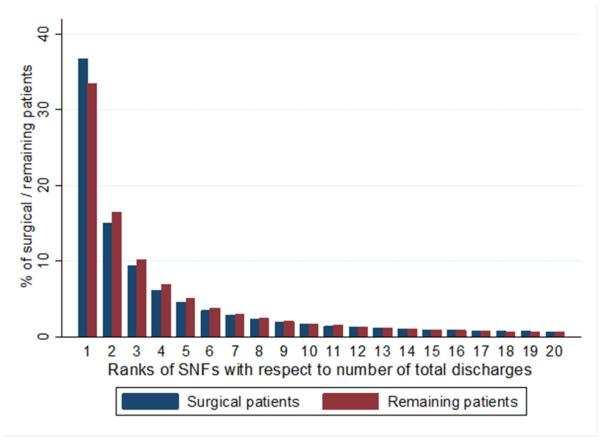

There were 138,163 patients with surgical interventions performed at 1,959 hospitals included in this analysis. The average age of patients was 79.8 (SD 7.64). Thirty-seven percent of patients underwent hip fracture repair, while 36% received total hip arthroplasty and 10% received CABG. Ninety percent of the population was white and the average hospital length of stay was 5.75 (SD 5.1) days (Table 1). More than half of the patients receiving one of the included surgical procedures at any given hospital were discharged to one of the three most preferred SNFs for that institution (Figure 1). The most preferred SNF received close to 40% of patients following one of the selected surgical interventions. A greater proportion of patients from our surgical group were discharged to the most preferred SNF than the remaining patients treated at that same hospital for other medical or surgical conditions (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Selected Surgical Patients | |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age (Mean/SD) | 79.84 (7.64) |

| White (%) | 90.28% |

| Black (%) | 4.36% |

| Female (%) | 68.71% |

| Clinical | |

| 30-day readmission rate | 11.41% |

| Mean Length of stay (days/SD) | 5.75 (5.10) |

| Elixhauser score (mean) | 2.52 |

| Deyo score (mean) | 1.08 |

| Skilled nursing facility characteristics | |

| Total no. of beds (mean/SD) | 119.72 (73.62) |

| Medicaid patients (%) | 40.16% |

| Multi-facility chain (%) | 55.22% |

| For profit (%) | 63.21% |

| Any MD extender (%) | 45.60% |

| Hospital's own SNF(%) | 7.76% |

| Hospital-based SNF(%) | 11.96% |

| Average deficiency score | 61.8 |

| Total no. of FTE RN (mean/SD) | 11.86 (9.70) |

| Total no. of FTE LPN (mean/SD)) | 17.9 (12.62) |

| Total no. of FTE CAN (mean/SD) | 50.87 (34.32) |

| Distance (km) | |

| Between home and SNF(median) | 8.68 |

| Between hospital and SNF(median) | 6.57 |

| Observations | 138,163 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of hospital-skilled nursing facility (SNF) linkages for patients receiving one of the five selected surgical procedures in this study (surgical patients) as compared to those hospitalized for other reasons (remaining patients).

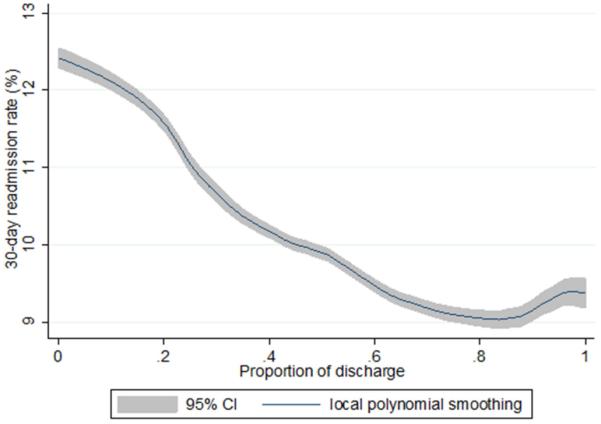

The 30-day readmission rate for the entire cohort was 11.4%. Of these patients, 5.5% of the cohort was readmitted with a primary diagnosis of sepsis. This ranged from a low of 3.2% of readmitted patients following CABG to a high of 6.9% of readmitted patients treated with lumbar spine surgery or hip fracture repair. Readmissions were highest among those who underwent colectomy or CABG (20.8% and 20.6%, respectively) and lowest for patients who received total hip arthroplasty (6.8%). A strong negative correlation (p<0.001) was observed between the proportion of surgical discharges received by a SNF and the rate of hospital readmission (Figure 2). For all surgical patients included in this investigation, SNFs receiving a small proportion of these individuals from a given hospital were found to have rehospitalization rates approximating 12.5% while SNFs receiving 80% of surgical discharges were found to have only a 9% readmission rate.

Figure 2.

30-day readmission rates based on the proportion of surgical discharges from a hospital to a particular skilled nursing facility (SNF)

Given the large size of our sample, most of the factors considered were found to be significant predictors of hospital-SNF referral (Appendix 1). Those factors with the largest effects included whether the SNF was owned by the hospital (RC 1.91, 95% CI [1.86, 1.95]), whether the SNF was hospital based (RC −0.4, 95% CI[−0.43, −0.36]) and the distance from a patient’s home to the SNF (RC −0.11 (−0.1056), 95% CI [−0.1063, −0.1050]).

Appendix.

Predictors of hospital-skilled nursing facility (SNF) referral as determined by a conditional (fixed effects) logit model.

| VARIABLES | (1) Coefficient (SE) |

P-values | (2) Marginal effect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance: home to SNF | −0.106 (0.000344) |

<0.001 | −0.1734 |

| Distance: hospital to SNF | −0.0712 (0.000326) |

<0.001 | −0.1186 |

| Total number of beds | −0.000884 (0.000106) |

<0.001 | −0.0015 |

| % paid by Medicaid | −0.0248 (0.000133) |

<0.001 | −0.0418 |

| Multi-facility SNF | 0.0401 (0.00676) |

<0.001 | 0.0683 |

| For profit | 0.130 (0.00755) |

<0.001 | 0.2188 |

| Any MD extender | 0.0404 (0.00678) |

<0.001 | 0.0689 |

| Hospital's own SNF | 1.907 (0.0237) |

<0.001 | 6.0824 |

| Hospital-based SNF | −0.396 (0.0183) |

<0.001 | −0.5953 |

| Average deficiency score | −0.00195 (5.96e-05) |

<0.001 | −0.0033 |

| Total no. of FTE RN | 0.0256 (0.000382) |

<0.001 | 0.0438 |

| Total no. of FTE LPN | 0.0163 (0.000437) |

<0.001 | 0.0278 |

| Total no. of FTE CNA | 0.00227 (0.000241) |

<0.001 | 0.0039 |

| Observations | 8,519,910 |

Note: Marginal effects are calculated as percentage change in likelihood of being discharged to an skilled nursing facility in response to a one unit of change in corresponding characteristics23. FTE – full time equivalent; RN – registered nurse; LPN – licensed practical nurse; CNA – certified nursing assistant; MD extender – nurse practitioner, physician assistant.

The results of the regression analysis confirmed that hospital-SNF linkage, as measured by the proportion of surgical discharges, was a significant predictor of readmission; with an increased proportion of surgical discharges decreasing the likelihood of readmission (RC −0.04 , 95% CI [−0.07, −0.02)]. This result suggests a 10% increase in the proportion of surgical discharges from a hospital to a particular SNF would result in a 4% reduction in rehospitalization rate. Hospital ownership of the receiving SNF was not found to be a significant predictor of readmission (RC 0.018, 95% CI [−0.0016, 0.036]). Patient age, medical co-morbidities, and hospital length of stay were also found to significantly increase the likelihood of readmission as did the percentage of Medicaid patients residing at a SNF (Table 2). Female sex significantly decreased the likelihood of readmission (RC −0.02, 95% CI[−0.028, −0.019]). The majority of these findings were preserved following IV analysis (Table 2). These determinations were also robust to sensitivity checks that limited consideration to hospitals with 25 or more surgical discharges (RC −0.03) and those with (RC −0.04) and without (RC −0.03) inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

Table 2.

The impact of Hospital-SNF linkage on 30-day readmission rates following linear regression (OLS) and Instrumental Variables (IV) analysis*.

| Variables | OLS (SE) | P-value | IV (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Proportion of

patients discharged to the SNF |

−0.04 (0.0083) | <0.001 | −0.060 (0.031) | 0.047 |

|

Proportion of

patients with Medicaid as a payer |

0.0002 (0.0001) |

0.002 | 0.0002 (0.0001) |

0.008 |

| Age | 0.002 (0.0001) | <0.001 | 0.002 (0.0001) | <0.001 |

|

Elixhauser

score>2 |

0.006(0.001) | <0.001 | 0.006(0.001) | <0.001 |

| Deyo score>2 | 0.014 (0.001) | <0.001 | 0.014 (0.001) | <0.001 |

| Female | −0.024 (0.002) | <0.001 | −0.024 (0.002) | <0.001 |

|

Hospital Length

of Stay |

0.006 (0.001) | <0.001 | 0.006 (0.001) | <0.001 |

- Only variables found to be statistically significant in linear regression analysis are presented. The insignificant variables we dropped are: no. of beds in a SNF, whether a SNF is multifunctional, for-profit, extension of any MD, a hospital’s own SNF or hospital-based SNF, a SNF’s average deficiency score, no. of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants; and patients’ age, race and gender.

In the subset analysis, hospital-SNF linkage was found to significantly reduce the likelihood of readmission for patients following lumbar spine surgery, CABG and hip fracture repair (Table 3). Estimating a 10% increase in the proportion of selected surgical discharges from a hospital to a particular SNF would be anticipated to result in a 4% reduction in readmission for patients receiving CABG, a 3% reduction in rehospitalizations following hip fracture surgery and a 4% reduction in readmission after lumbar spine surgery.

Table 3.

The impact of Hospital-SNF linkage on 30-day readmission rates for each of the surgical procedure groups following linear regression (OLS) and Instrumental Variables (IV) analysis.

| Variables | OLS (P-value) | IV (P-value) | No. of observations | Avg. 30-day readmission rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lumbar Spine

Surgery |

−0.047 (0.024) | −0.185 (0.102) | 22,345 | 11.3% |

|

Total hip

arthroplasty |

−0.012 (0.156) | 0.005 (0.910) | 50,344 | 6.8% |

|

Hip fracture

repair |

−0.037 (0.005) | −0.121 (0.017) | 50,794 | 13.4% |

| Colectomy | −0.544(0.082) | −8.556(0.937) | 742 | 20.8% |

|

Coronary Artery

Bypass Grafting (CABG) |

−0.085 (0.019) | 0.055(0.763) | 13,938 | 20.6% |

Discussion

The current healthcare environment is increasingly focused on ways to optimize patient care following surgical intervention, including a particular emphasis on reducing hospital readmission following discharge.1,2,3,6 At present, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has instituted penalties for hospitals that are found to have higher rates of rehospitalization than those deemed to be clinically acceptable.1,2,3 Furthermore, poor performance in the coordination of post-surgical care may adversely impact reimbursement and financial viability for organizations participating in bundled payment programs or ACOs.1-5,25,26,27 The enhanced integration of care that may be associated with hospital linkage to SNFs, and consequent reductions in complications and miscommunications that could contribute to hospital readmissions are clearly advantageous to both patients and hospitals.

The present study considered patients who received one of five surgeries, inclusive of both elective and urgent surgical procedures in the fields of general surgery, cardiac surgery, orthopedics and neurosurgery.2,5,7,25,26,27 The results of this work demonstrated a strong correlation between the proportion of surgical patients discharged to a SNF and the likelihood of readmission. Specifically, rehospitalization rates were reduced among those SNF facilities that received a higher proportion of a hospital’s surgical discharges. These findings were largely preserved following IV analysis and were particularly robust for patients who received lumbar spine surgery, CABG and hip fracture repair, indicating that readmission reductions following these procedures may be more sensitive to the benefits of increased hospital-SNF linkage. Conversely, patients receiving colectomy or THA may be less sensitive to these effects. Increasing the proportion of patients referred from a hospital to a SNF following lumbar spine surgery, CABG and hip fracture repair by 10% would be anticipated to lead to concomitant reductions in readmission in the range of 3-4%.

The effect of SNF-hospital linkage on readmission for surgical patients can likely be attributed to a number of factors, given the enhanced need for integrated care among surgical patients in the post-acute period. If we accept the premise that most, if not all, post-surgical readmissions occur as a result of a medical or surgical complication1,2,3,7, SNFs receiving a larger proportion of a hospital’s surgical discharges may be more effective at minimizing the development of such events. These highly linked SNFs may have more efficient triage processes and established better communication channels that allow for the effective management of peri-operative issues. In less integrated post-acute settings, similar peri-operative problems might progress to a complication necessitating readmission. Improved communication between the treating hospital, surgical care teams and the SNF may also contribute to enhanced patient care and a consequent reduction in the events associated with rehospitalization.1 For example, increased familiarity on the part of SNF staff with surgical providers may lower barriers to contacting the team regarding indications of clinical deterioration in a surgical patient. Early action guided by the operative surgeon, their nurse practitioner, or physician assistants may then ultimately obviate the need for urgent re-referral to the surgical clinic, emergency room or an inappropriate rehospitalization.

Risk-based reimbursement models, inclusive of ACOs and bundled payment initiatives, render providers, hospitals and SNFs responsible for the total cost of surgical care.4,5,26,27 A sizable proportion of existing variation in Medicare payments around surgical conditions has been attributed to the post-acute period.5,26,27 Reduced costs associated with post-acute care, including optimized SNF services and reduced rates of readmission that result from enhanced hospital-SNF linkage would lead to increased savings for Medicare as well as the responsible healthcare organizations.

The strengths of this study include a large cohort of patients derived from national 100% Medicare data as well as a diverse sample of surgical procedures with readmission rates comparable to those reported elsewhere in the literature.2,3,7 We recognize, however, that there are limitations associated with this work. Foremost, this analysis was conducted using Medicare data and therefore findings may not be applicable to younger patients receiving similar surgical interventions, or individuals using different types of health insurance. Similarly, given the design of this study and the data available, the results are limited to patients referred to SNFs and should not be extrapolated to those discharged to other providers of post-acute rehabilitation, such as long-term acute care facilities. It is important to note, however, that our findings were robust to sensitivity testing that considered hospitals with and without inpatient rehabilitation. Second, as this study relied on administrative data, there is the potential for confounding from unmeasured variables not reported to Medicare or inaccurately captured in the datasets used. We attempted to control for this to the best of our ability using IV analysis, with the distance from patients’ home to the SNF as the instrumental variable. Such an approach has been postulated to imitate random assignment and allows for the generation of more conservative and unbiased estimates.1,24 Viewed in this light, it is encouraging that most of our main effects were preserved following IV testing. Third, given the use of claims data, we were unable to adjust for the influence of patient frailty as described in other publications.28 It should be noted, however, that extant frailty indices28 overlap with a number of variables included for adjustment in our regression model and we did control for the presence of co-morbidities using accepted Elixhauser and modified Charlson scores2,3,5,6-9,25,26,27. Lastly, as our data are from 2011 and 2012, they may not be entirely reflective of the current healthcare environment, particularly since readmission penalties associated with the implementation of the ACA were only instituted in 2012.

In spite of these limitations, these study results hold important meaning for surgeons, hospitals, third party payers and government entities. Based on the findings presented here, it could be anticipated that enhanced association between hospitals and select SNFs may result in meaningful reductions in hospital readmission following surgical intervention. Hospitals should be encouraged to seek integrated relationships with one or more SNFs who would be designated the preferred facilities for referral of post-surgical patients. Based on our study results, it does not appear that such SNFs necessarily need to be owned by the referring hospital. Such enhanced linkage between hospitals and SNFs may then reduce readmissions and presumably the medical and surgical complications that precipitate the need for rehospitalization. This type of SNF-hospital integration will likely also be associated with better continuity and quality of care, improved patient satisfaction and, in the era of the ACA, reduced financial penalties for hospitals and affiliated healthcare organizations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (Grant P01 AG027296) to Brown University with a sub-contract to Harvard Medical School. The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dimick JB, Miller DC. Hospital readmission after surgery: No place like home. Lancet. 2015;386:837–838. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shih T, Dimick JB. Reliability of readmission rates as a hospital quality measure in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1214–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjoding MW, Iwashyna TJ, Dimick JB, Cooke CR. Gaming hospital-level pneumonia 30-day mortality and readmission measures by legitimate changes to diagnostic coding. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):989–995. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupree JM, Patel K, Singer SJ, West M, Wang R, Zinner MJ, Weissman JS. Attention to surgeons and surgical care is largely missing from early medicare accountable care organizations. Health Aff. 2014;33(6):972–979. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller DC, Ye Z, Gust C, Birkmeyer JD. Anticipating the effects of accountable care organizations for inpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):549–554. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of Hospital-SNF Referral Linkages on Rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6):1898–1919. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendren S, Morris AM, Zhang W, Dimick J. Early discharge and hospital readmission after colectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(11):1362–1367. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822b72d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman M, Gozalo P, Tyler D, Grabowski DC, Trivedi A, Mor V. Dual Eligibility, Selection of Skilled Nursing Facility, and Length of Medicare Paid Postacute Stay. Med Care Res Rev. 2014 May 14;71(4):384–401. doi: 10.1177/1077558714533824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castle NG. Nursing home caregiver staffing levels and quality of care. J Applied Gerontol. 2008;27(4):375–405. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castle NG, Anderson RA. Caregiver staffing in nursing homes and their influence on quality of care: Using dynamic panel estimation methods. Med Care. 2011;49(6):545–552. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fbca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyer K, Thomas KS, Branch LG, Harman JS, Johnson CE, Weech-Maldonado R. The influence of nurse staffing levels on quality of care in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2011 Oct;51(5):610–616. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson DG. Nursing home consumer complaints and quality of care: A national view. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):347–368. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steffen TM, Nystrom PC. Organizational determinants of service quality in nursing homes. Hospital and Health Services Administration. 1997;42(2):179–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter MW, Porell FW. Variations in hospitalization rates among nursing home residents: the role of facility and market attributes. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):175–191. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank quart. 2004;82(2):227–256. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Design for Nursing Home Compare Five-Star Quality Rating System: Technical users’ guide. 2010 https://www.cms.gov/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/usersguide.pdf. Accessed February, 15, 2010.

- 19.Zinn J, Mor V, Feng Z, Intrator O. Determinants of performance failure in the nursing home industry. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Mar;68(5):933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Intrator O, Castle NG, Mor V. Facility characteristics associated with hospitalization of nursing home residents: results of a national study. Med Care. 1999 Mar;37(3):228–237. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinnott RW. Virtues of the Haversine. Sky Telescope. 1984;68(2):159–159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman M, Grabowski DC, Gozalo PL, Thomas KS, Mor V. Are Dual Eligibles Admitted to Poorer Quality Skilled Nursing Facilities? Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):798–817. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman M, Foster AD. Racial segregation and quality of care disparity in US nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2015;39:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwashyna TJ, Kennedy EH. Instrumental variable analyses: Exploiting natural randomness to understand causal mechanisms. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):255–260. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201303-054FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellimoottil C, Miller S, Ayanian JZ, Miller DC. Effect of insurance expansion on utilization of inpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(8):829–836. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Large variations in Medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff. 2011;30(11):2107–2115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenfeld AJ, Harris MB, Liu H, Birkmeyer JD. Variations in Medicare payments for episodes of spine surgery. Spine J. 2014;14:2793–2798. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S. Measuring Frailty Using Claims Data for Pharmacoepidemiologic Studies of Mortality in Older Adults: Evidence and Recommendations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:891–901. doi: 10.1002/pds.3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]