Abstract

Introduction:

According to the WHO, 70–80% population in developing countries still relies on nonconventional medicine mainly of herbal origin. Even in developed countries, use of herbal medicine is growing each year. Pain is an unpleasant feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli. Traditionally, different plant parts of Ficus benghalensis are claimed to have several analgesic properties. Few scientific evidences support these uses. Interestingly, still others contradict these uses. It was shocking to find very scarce scientific studies trying to solve the mystery.

Materials and Methods:

It was a quantitative experimental study in Swiss albino mice of either sex. Sample size was calculated using free sample size calculating software G*Power version 3.1.9.2. Hot-plate test and tail-flick test were central antinociceptive paradigms. Writhing test was peripheral model for pain. Test drugs were aqueous root extracts of F. benghalensis at 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg mouse weight prepared by Soxhlet method. Suitable negative and positive controls were used. The experimental results were represented as mean ± standard deviation statistical level of significance was set at P < 0.05. For calculation, parametric test - one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or nonparametric test - Mann–Whitney U-test was appropriately used.

Results:

Hot-plate reaction time at 100 mg/kg (13.64 ± 1.30 s) and 200 mg/kg (10.32 ± 2.23 s) were nonsignificant (P = 0.425 and P = 0.498, respectively) compared to negative control (11.87 ± 1.92 s). One-way ANOVA revealed nonsignificant (P = 0.178) between-group comparison in mean tail-flick reaction time. Test drug at 200 mg/kg produced statistically significant more writhing (36.00 ± 14.85 in 10 min) than negative control, normal saline (11.83 ± 12.43 in 10 min) or the positive control, Indomethacin (3.50 ± 5.21 in 10 min), P value being 0.031 and 0.003, respectively.

Conclusion:

Aqueous root extracts of F. benghalensis at 200 mg/kg produces statistically significant writhing.

Keywords: Analgesic, animal models, Ficus, pain

Introduction

The use of plant parts as medicine is as old as human civilization itself.[1] Even today, our existence cannot be imagined without plants serving different medicinal purposes. According to the WHO, 70–80% population in developing countries still relies on nonconventional medicine mainly of herbal origin. Even in developed countries, use of herbal medicine is growing each year. In allopathy, pharmacological screening of plants often provides basis for developing new lead molecules.[2,3]

Pain is an unpleasant feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli such as pinching the skin, burning a finger, or putting alcohol on a cut.[4] Subjective sensation of pain can be blocked centrally (opioid-like) or peripherally (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [NSAID] - like).[5]

Traditionally, different plant parts of Ficus benghalensis are claimed to have several analgesic properties. Nadkarni mentioned its use in menorrhagia. An ancient Indian mythological book writes “A decoction of leaf buds and aerial roots of F. benghalensis, mixed with honey, can be given for any burning sensation.”[6] It has also been recommended for rheumatism and skin disorders such as sores.[7] The bark is considered useful in burning sensation, ulcers, and painful skin diseases.[8] It can be used in inflammation and toothache.[8]

Few scientific evidences also throw positive evidence. Garg and Paliwal concluded that extracts of F. benghalensis did have significant analgesic and antipyretic activities from hot-plate, writhing, and yeast-induced hyperthermia models.[9] Leaf extracts have shown remarkable benefits on freunds adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats.[10]

Again, a recent study by Thakare et al. concluded that methanolic extracts of F. benghalensis bark did have anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in animal models.[11] Mahajan et al. verified significant analgesic activities of methanolic extract of leaves of F. benghalensis.[3]

On the other hand, there are some negative scientific evidences. Deraniyagala et al. studied the effects of aqueous leaf extract of F. benghalensis on nociception in rats. The results showed that the aqueous leaf extract of the of F. benghalensis had no analgesic effects but marked and significant hyperalgesic effect in male rats.[12]

Although there are several articles claiming usefulness of F. benghalensis parts in pain and inflammation, it was shocking to find very scarce scientific studies trying to scrutinize these claims, mostly anecdotal. Again scientific studies done elsewhere may not be the answer to different climatic perspective of Nepal.

This study was undertaken to answer whether aqueous roots of F. benghalensis have any effect in pain in animal models or not.

Materials and Methods

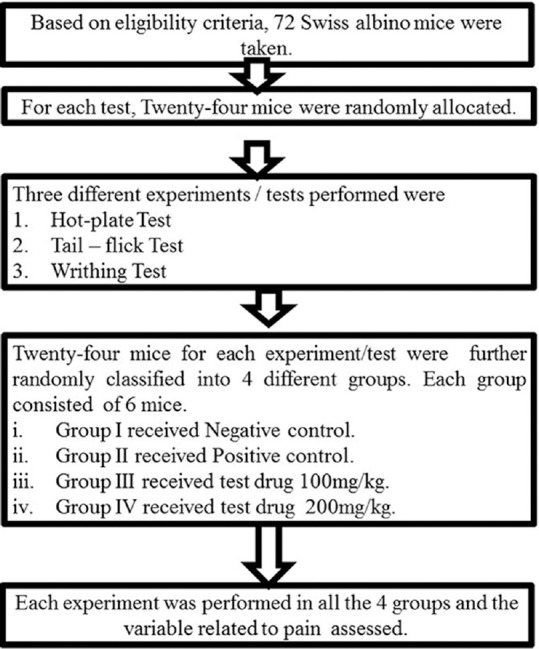

Experiments [Figure 1] were conducted in the Laboratory of Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS), Dharan, Nepal.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart

Geographical coordinates of the studied plant are 26° 49' 0” North, 87° 17' 0” East. Annual average temperature varies from 5% to 21% centigrade. Average rainfall varies from 0 mm/day in January to 128 mm/day in July.

Sample size was calculated using free sample size calculating software G*Power version 3.1.9.2 (Franz, Universitat Kiel, Germany). With power of 80%, 0.05 level of statistical significance and effect size of 0.8, sample size for each test was calculated to be 24. Seventy-two mice were randomly assigned into one of the three experimental groups. It was a quantitative experimental study in mice.

Inclusion criteria

Swiss albino mice of either sex

Weighing 20–30 g.

Exclusion criteria

Any apparent disease or handicap.

Test drug preparation

A F. benghalensis tree was authenticated by a botanist. About 2.5 kg aerial roots of the tree was carefully collected, thoroughly washed with tap-water, shade-dried for several days, and pulverized to fine powder in a mixer. About 2 kg of resulting crude root-powder was extracted in several batches using soxhlet apparatus [Figure 2] (Jain Scientific Glass Works Ambala Cantt; Extraction Pot: 250 ml; Soxhlet chamber size: 100 ml; Heater: DICA India). Distilled water was used for extraction. Each batch was extracted for an approximately 24 h. Thus produced aqueous root extract was heated in 50°C for a brief time interval, stopped just before the apparently saturated solution precipitated and left in room temperature until the moisture dried. 2 kg crude root-powder yielded 102.68 g extract (5.13%) by soxhlet method.[13] Thus resulted dried powder extract was safely stored in a dry air-tight plastic container until the day of the experiment.[14] On the experiment day, 20 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml solutions in distilled water were prepared by serial dilution such that 1 ml/100 g mouse body weight could be injected into the mice in test-drug group for the desired test dose of 200 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, respectively. On the day of experiment, the previous day solutions were discarded and fresh solutions prepared.

Figure 2.

Soxhlet apparatus in use

Timing of the drug administration

All per os (PO) drugs were carefully administered with the help of orogastric tube approximately 60 min before the intended test. All parenteral drugs were given intraperitoneal (IP).[15,16,17]

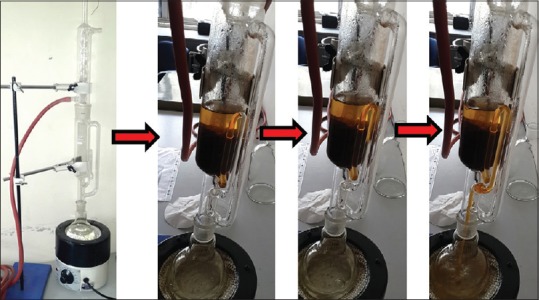

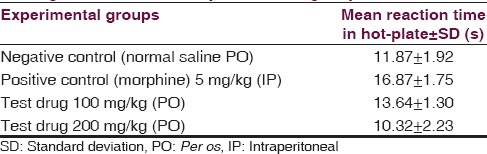

Hot-plate test

The method validated by Williamson et al., and Eddy and Leimback was used.[18] The thermal noxious stimuli were given to a mouse by placing it on a thermostatically controlled hot-plate [Figure 3] (UGO Basile, Italy) at 55–56°C and the reaction time recorded. Reaction time was taken as the period between placing the mouse in the hot-plate and the time when it either jumped or licked its paws, whichever occurred first. A cutoff time of 15 s was used to minimize injury to paws. Morphine at 5 mg/kg IP was the positive control for the test and was administered approximately 15 min before the test.[17]

Figure 3.

Mouse licking forefoot in hot-plate test

Tail-flick test

Radiant noxious stimuli were given to the proximal one-third of the mouse-tail by directing an infrared light of 50 unit intensity [Figure 4] (Tail-Flick Unit, UGO Basile, Italy). Response was obtained by observing the interval between the stimuli exposure and withdrawal of the tail (reaction time). A maximum radiation exposure period (cutoff time) was 6 s. Morphine at 5 mg/kg IP was the positive control for this test and was administered approximately 15 min before the test.[17]

Figure 4.

Tail-flick test

Writhing test

Approximately, 1 h after the oral drug administration, 0.6% acetic acid at 60 mg/kg[17] was injected IP to every mouse. Then, the number of writhes (stretching of abdomen with simultaneous extension of one of the hind limbs) was counted for ten immediate minutes. Antinociception would be expressed as the difference in the number of writhes between normal saline and test drug group. Positive control was indomethacin 20 mg/kg, PO.[19]

Drugs and chemicals used in experimental models

Test drug-aqueous solution of aerial root extracts of F. benghalensis 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg PO

Negative control in all three models: Normal saline (0.90% w/v of NaCl) PO

-

Positive control

-

Inducing agents

- Writhing inducing agent: 0.6% acetic acid at 60 mg/kg IP.[17]

All drugs and chemicals were diluted in distilled water such that 1 ml is for 100 g mouse weight, i.e., 25 g mouse receives 0.25 ml volume dose with 1 ml insulin syringe divided into 100 equal parts.

Statistical analysis

The experimental results were represented as mean ± standard deviation SPSS version 21 (IBM) was used. For normally distributed dependent variable, parametric test - one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison was applied. For those, not normally distributed, nonparametric test - Mann–Whitney U-test was employed for comparison. Statistical level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Before the conduction of the experiment, ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee on Animal Research of BPKIHS. Maximum precaution was taken to reduce the pain and injury to the animals in the course of the experiment, yet not compromising the standard of the experiment. Appropriate help was procured from expert experimental animal handlers during the course of study.

Results

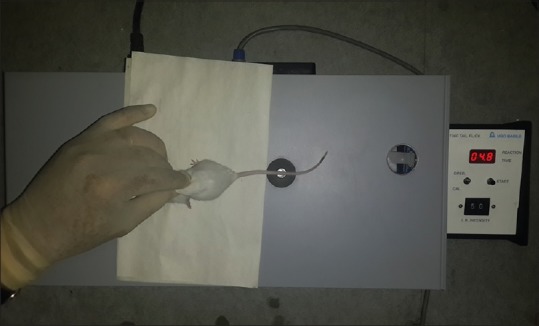

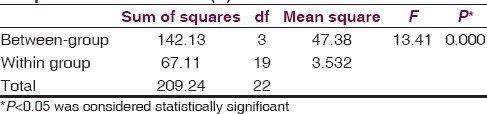

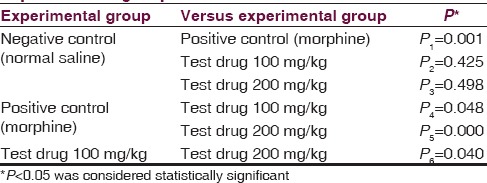

Hot-plate test [Table 1]

Table 1.

Comparison of mean hot-plate reaction-time among four different experimental groups

One-way ANOVA [Table 2] revealed a significant (P = 0.000) influence of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis on mean hot-plate reaction time among Swiss albino mice. Multiple Comparisons [Table 3] by Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc tests (α = 0.05) revealed nonsignificant (P2 =0.425) effect of 100 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis compared to normal saline. Again, there was nonsignificant (P3 =0.498) effect of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis at 200 mg/kg compared to normal saline. However, group receiving 100 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis had significantly (P4 =0.048) shorter mean hot-plate reaction time (13.64 s ± 1.30 s) compared to Morphine-group (16.87 s ± 1.75 s). Similarly, group receiving 200 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis had significantly (P5 =0.000) shorter mean hot-plate reaction time (10.32 s ± 2.23 s) compared to morphine-group (16.87 s ± 1.75 s).

Table 2.

One-way analysis of variance test - mean hot-plate reaction time (s)

Table 3.

Tukey highly significant difference post hoc tests comparing mean hot-plate reaction time among experimental groups

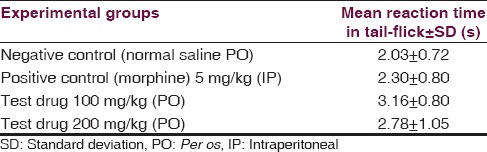

Tail-flick test [Table 4]

Table 4.

Comparison of mean tail-flick reaction time among four different experimental groups

One-way ANOVA [Table 5] revealed nonsignificant (P = 0.178) influence of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis on tail-flick antinociceptive test among Swiss albino mice.

Table 5.

One-way analysis of variance test-mean tail-flick reaction-time (s)

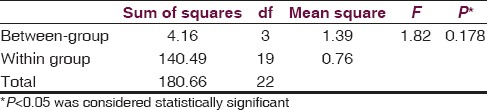

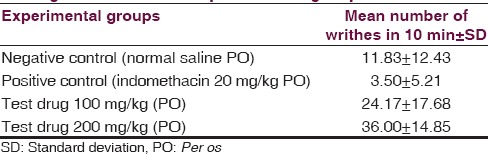

Writhing test [Table 6 and Figure 5]

Table 6.

Comparison of number of writhing in 10 min among four different experimental groups

Figure 5.

Comparison of number of writhing in 10 min among four different experimental groups

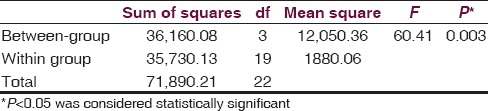

One-way ANOVA [Table 7] revealed a significant (P = 0.003) influence of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis on acetic acid-induced writhing test among Swiss albino mice.

Table 7.

One-way analysis of variance test - mean number of writhes in 10 min duration

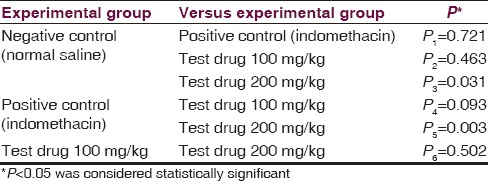

Multiple comparisons [Table 8] by Tukey HSD post hoc tests (α =0.05) showed 100 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis had nonsignificant effect (P2 =0.463) compared to negative control (normal saline). However, group receiving 200 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis significantly (P3 =0.031) produced more writhing in 10 min duration (36.00 ± 14.85) compared to normal saline group (11.83 ± 12.43). Again, 100 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis had nonsignificant effect (P4 =0.093) compared to Indomethacin. However, group receiving 200 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis significantly (P5 =0.003) produced more writhing compared to indomethacin-group (3.50 ± 5.21).

Table 8.

Tukey analysis of variance post hoc tests - comparing mean number of writhes in 10 min among experimental groups

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on effect of root extracts of F. benghalensis in pain in animal models from Nepal. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that the high doses (2000 mg/kg) were tolerated without any acute signs of toxicity or mortality. Therefore, one tenth of this dose[10] (i.e., 200 mg/kg) was considered as the highest evaluation dose for pharmacological studies.

Subjective sensation of pain can be blocked either at the central or peripheral level.[5] Peripherally, the formation of pain mediators, i.e., prostaglandins can be blocked either by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (NSAID-like) or phospholipase A2(steroid-like). Centrally, pain sensation can be blocked by stimulating μ receptor (opioid-like).[21]

In our experiments, test drugs at both doses did not produce statistically significant analgesia in the central antinociceptive paradigms (hot-plate and tail-flick).

Unexpectedly, the test drug produced statistically significant writhing similar to known peripheral irritant acetic acid at higher dose (200 mg/kg). Thus, the aqueous extracts of aerial roots of F. benghalensis in our experiments pointed toward acetic acid such as peripheral hyperalgesic effect rather than analgesic effect as believed earlier. Our results, therefore, do not validate the usefulness of F. benghalensis aerial roots in painful conditions. Deraniyagala et al. also reported marked and significant hyperalgesic effect of aqueous leaf extract of F. benghalensis in male rats.[12]

Most past studies have, however, shown that different plant-parts, namely bark[9] and leaves[3,9] did have analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties.

The bark extracts of other taxonomically close species of Ficus, namely Ficus racemosa, Ficus religiosa, Ficus insipida, Ficus elastica, Ficus indica, and Ficus carica were also found to have analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities.[6]

Limitations and scope for further study

Although our test result has started a new argument, we assume certain shortcomings in our endeavor.

We did not have much past evidences to compare it with

Distinct climate, soil, and environment of Eastern Nepal might have produced different properties that may reduce the global applicability of our findings

In lack of phytochemical analysis accompanied by cause-effect establishment of individual phytoconstituents, we remain skeptical about extrapolating our report to other plant parts than aerial roots. Further, in-depth research disclosing the phytoconstituents responsible for each neuropharmacological activity along with their correct mode of action is desperately needed

Individual differences in anatomy, organ function, drug absorption, and metabolism among animals are among the myriad of other differences that could have given us inadequate and distinct information

Single acute dose-effect was studied. Subacute and chronic dose-effect could not be extrapolated from these data

We studied only two most relevant doses of test drug. More doses are needed to establish statistically significant dose-effect relationship

In spite of all these, we consider our study has high internal and external validity, and our findings can be replicated elsewhere.

Recommendation

Although technically more demanding, phytomolecular identification followed by in vitro receptor-ligand binding studies may be the answer to all the unanswered questions even without sacrificing the animals.

Conclusion

Aqueous root extracts of F. benghalensis at 200 mg/kg produces statistically significant writhing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Myriad efforts from Mr. Gokarna Bhandari deserve a special appreciation. His skillful acumen in handling animals, practical knowledge sharpened by experience needs special mention.

References

- 1.Nadkarni KM, Nadkarni AK. Mumbai; Indian Materia Medica: The University of Michigan, Popular Book Depot. 1955 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan K. Some aspects of toxic contaminants in herbal medicines. Chemosphere. 2003;52:1361–71. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahajan MS, Gulecha VS, Khandare RA, Upaganlawar AB, Gangurde HH, Upasani CD. Anti-edematogenic and analgesic activities of Ficus benghalensis. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2012;2:100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonica JJ. The need of a taxonomy. Pain. 1979;6:247–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. USA: McGraw-Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrotta JA. Healing Plants of Peninsular India. New York: CABI Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murti K, Kumar U, Kiran D, Kaushik MF. Formulation and evaluation of Ficus benghalensis and Ficus racemosa aquoues extracts. Am J Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;9:219–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaiswal R, Ahirwar D. A literature review on Ficus bengalensis. Int J Adv Pharm Res. 2013;5:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg VK, Paliwal SK. Analgesic and anti-pyretic activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Ficus benghalensis. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:231–4. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.82957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhardwaj L, Patil K. Study on efficacy of treatment with Ficus benghalensis leaf extracts on freunds adjuvant induced arthritis in rats. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2010;2:4–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakare VN, Suralkar AA, Deshpande AD, Naik SR. Stem bark extraction of Ficus bengalensis Linn for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity in animal models. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deraniyagala SA, Ratnasooriya WD, Perera PS. Effect of aqueous leaf extract of Ficus benghalensis on nociception and sedation in rats. Vidyodaya J Sci. 2013;11:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manirakiza P, Covaci A, Schepens P. Comparative study on total lipid determination using Soxhlet, Roese-Gottlieb, Bligh and Dyer, and modified Bligh and Dyer extraction methods. J Food Compost Anal. 2001;14:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sluiter A, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D. Determination of extractives in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedure. Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulkarni SK. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 3rd ed. Chandigarh: Panjab University Chandigarh, Vallabh Prakashan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh MN. Fundamentals of Experimental Pharmacology. 5th ed. Kolkata: Hilton & Company; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel H, Vogel WH, Schölkens BA, Sandow J, Müller G, Vogel WF. Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Pharmacological Assays. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amabeoku GJ, Kabatende J. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of leaf methanol extract of Cotyledon orbiculata L. (Crassulaceae) Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2012;2012:862625. doi: 10.1155/2012/862625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koster R, Anderson M, DeBeer EJ. Acetic acid for analgesic screening. Vol. 18. Bethesda, MD: 1959. pp. 412–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh KK, Rauniar GP, Sangraula H. Experimental study of neuropharmacological profile of Euphorbia pulcherrima in mice and rats. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:311–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.102612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripathi KD. Essentials of Medical Pharmacology. 7th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]