Abstract

The regulation of divalent metal ion transporter DMT1, the primary non-heme iron importer in mammals, is critical for maintaining iron homeostasis. Previously we identified ubiquitin-dependent regulation of DMT1 involving the Nedd4 family of ubiquitin ligases and the Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 adaptors. We also established the in vivo function of Ndfip1 in the regulation of DMT1 in the duodenum of mice. Here we have studied the function of Ndfip2 using Ndfip2-deficient mice. The DMT1 protein levels in the duodenum were comparable in wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice, as was the transport activity of isolated enterocytes. A complete blood examination showed no significant differences between wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice in any of the hematological parameters measured. However, when fed a low iron diet, female Ndfip2−/− mice showed a decrease in liver iron content, although they maintained normal serum iron levels and transferrin saturation, compared to wild type female mice that showed a reduction in serum iron and transferrin saturation. Ndfip2−/− female mice also showed an increase in DMT1 expression in the liver, with no change in male mice. We suggest that Ndfip2 controls DMT1 in the liver with female mice showing a greater response to altered dietary iron than the male mice.

Iron is an essential element for the normal functioning of cells and for animal survival. Iron uptake and metabolism are complex and highly regulated processes, which involves a number of enzymes, transporters and regulatory proteins1. Iron levels are tightly controlled, as too little iron results in anemia, whereas elevated iron levels can lead to tissue damage and fibrosis due to the generation of reactive oxygen species. The divalent metal-ion transporter-1 (DMT1; also known as DCT1 and Slc11a2) is the primary importer of non-heme iron, and is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, with highest expression in the proximal duodenum (main site of iron uptake)2 and liver (main site of iron storage)3. The importance of DMT1 in the iron regulatory cycle is demonstrated by the fact that mutations in both humans and rodents result in severe hypochromic microcytic anemia4,5,6,7.

DMT1 expression and function are regulated by dietary iron availability through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms, including modification by ubiquitination8. Ubiquitination is well known for its role in regulating ion channels and transporters9. Ubiquitin ligases, which catalyse the transfer of ubiquitin to the substrate, confer specificity to the system by targeting specific proteins. The Nedd4 family are members of the HECT class of ubiquitin ligases, which bind to their targets directly through WW domains on the ligase interacting with proline-rich PPxY (PY) motifs on the substrate10. Members of this family, particularly Nedd4 and Nedd4-2, are involved in regulation of membrane proteins, including ion channels and transporters10. A well characterised example of this is the regulation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by Nedd4-2, where the WW domains of the ligase directly interacts with the PY motifs present within the three ENaC subunits11,12,13. In some cases the substrates of the Nedd4 family lack PY motifs and the interaction can be mediated through adaptor or accessory proteins. Two such adaptor proteins are Ndfip1 and Ndfip2, initially identified by us as Nedd4 WW domain interacting proteins14,15. In previous studies, we found that DMT1 is ubiquitinated by the Nedd4 family members Nedd4-2 and WWP2 in vitro, and this requires Ndfip1 and/or Ndfip28,16,17. In mice deficient in Ndfip1 we found increased duodenal DMT1 levels and activity, leading to increased iron uptake and storage in liver16,18. Interestingly, Ndfip1 is also known to be upregulated in neurons in response to divalent metals, such as cobalt, and protects neurons against metal ion toxicity via Nedd4-2-mediated DMT1 ubiquitination and down regulation17. Furthermore, Ndfip1 has been shown to regulate DMT1-dependent iron levels in the brain and play a role in Parkinson’s disease pathology19. These studies indicate that Ndfip1 plays a critical role in iron homeostasis in vivo. However, the in vivo function of Ndfip2 remains unknown.

In this study we report that in contrast to Ndfip1, Ndfip2 is not required for duodenal DMT1 regulation but is likely to play a role in the regulation of DMT1 in the liver, particularly in female mice, which appear to have an increased sensitivity for iron perturbations. We suggest that both Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 are required for regulating DMT1 in vivo, but they function in a context and tissue specific manner.

Results

Characterisation of Ndfip2 −/− mice

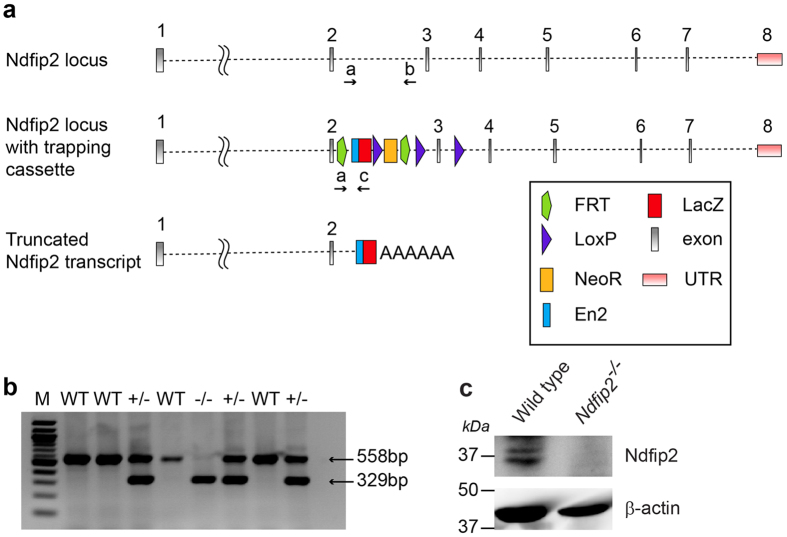

The Ndfip2−/− mice used in this study were generated by The European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM) by inserting a targeting vector cassette into intron 2 of the Ndfip2 gene (Fig. 1a). This disruption results in a truncated transcript expressing exon 1 and 2 fused to lacZ (Fig. 1a). To genotype these mice, PCR was performed using a triplex reaction containing the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. PCR with primers “a” and “b” produces a 558 bp band, indicating the presence of the Wild type (WT) locus. PCR with primers “a” and “c” yielded a band of 329 bp, indicating the disrupted locus (Fig. 1b). Immunoblotting confirmed that no detectable Ndfip2 protein was produced in the Ndfip2−/− samples (Fig. 1c), showing that the knockout results in a null allele.

Figure 1. The generation of mice homozygous for a disrupted Ndfip2 gene.

(a) The knockout mice were generated by EUCOMM. Location of the inserted trapping cassette within intron 2 of the Ndfip2 gene, resulting in a truncated transcript that encodes exons 1 and 2. The common forward primer (a), wild type reverse primer (b) and knockout reverse primer (c) are indicated. (b) PCR results from one litter produced by two heterozygous parents showing the sizes of the wild type (558 bp) and knockout (329 bp) bands. WT, wild type; M, marker. (c) Immunoblot showing the absence of Ndfip2 protein in Ndfip2−/− spleen tissue.

Ndfip2−/− mice have no developmental defects or gross anatomical abnormalities, and they live to an age comparable to WT mice (Ndfip2−/− mice were followed up to 24 months). This is in contrast to Ndfip1−/− mice, which develop a severe inflammatory phenotype and do not survive past 14 weeks of age20.

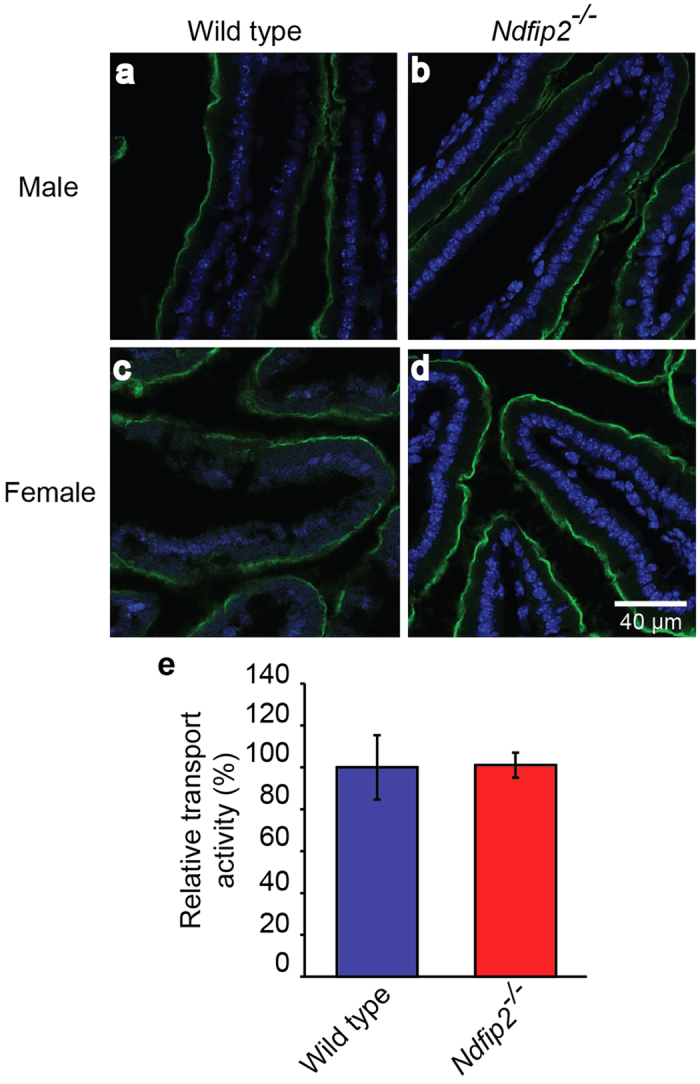

Ndfip2 is not required for DMT1 regulation in the duodenum

In vitro studies using CHO cells stably expressing Myc-tagged DMT1 have shown that overexpression of both Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 results in lower DMT1 activity16. Additional studies showed that Ndfip1−/− mice have increased iron deposits in their livers16 and that Ndfip1 is important for DMT1 regulation in the duodenum under low iron conditions18. However, the in vivo role for Ndfip2 has not been investigated. To determine the importance of Ndfip2 in DMT1 regulation in mice, we fed Ndfip2−/− mice either a normal or low iron diet for three weeks. Immunostaining of duodenum of male mice fed a low iron diet showed no difference in DMT1 levels between WT and Ndfip2−/− mice (Fig. 2a,b). To determine whether the effect of Ndfip2 on DMT1 regulation in the duodenum was sex-specific, we also stained duodenum from female mice; these also showed no significant differences between WT and knockout mice (Fig. 2c,d). Furthermore, isolated enterocytes did not show any increase in transport activity in Ndfip2−/− mice (Fig. 2e). This is in contrast to the Ndfip1−/− mice, which show an increase in DMT1 staining in the duodenum and an increase in transport activity in isolated enterocytes18. Taken together, these data suggest that Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 function differently in regulating DMT1 in vivo.

Figure 2. Ndfip2-deficient mice show normal DMT1 expression and activity.

DMT1 expression on the apical surface of the duodenum (green) of (a) male wild type and (b) Ndfip2−/− mice, and (c) female wild type and (d) Ndfip2−/− mice fed a low iron diet for three weeks. Representative images from n = 4. Blue shows DAPI staining of the nuclei. (e) DMT1 relative transport activity as measured by the fluorescence quenching assay in enterocytes isolated from wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice fed a low iron diet show no significant difference. Data represented as mean ± s.e.m.; n = 5.

As perturbations in iron homeostasis often manifest in abnormal hematological parameters, we performed a complete blood examination on WT and Ndfip2−/− mice. Again, unlike in the Ndfip1−/− mice18, none of the parameters showed a significant difference between the WT and Ndfip2−/− mice in either males or females (Table 1). Interestingly, male mice seemed less affected by the low iron diet than females. While there was a significant decrease in mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) and red cell distribution width (RDW) with a corresponding increase in red blood cell (RBC) count in mice on the low iron diet as would be expected in iron-deficient anemia, there was no significant difference in hemoglobin or hematocrit as there is in the females, indicating that male mice are perhaps less sensitive to perturbations in iron levels than females.

Table 1. Hematological parameters in male and female mice fed a low or normal iron diet.

| Male |

Female |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low iron diet |

Normal diet |

Low iron diet |

Normal diet |

|||||

| Wild type | Ndfip2−/− | Wild type | Ndfip2−/− | Wild type | Ndfip2−/− | Wild type | Ndfip2−/− | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 104.4 ± 11.5 | 111.0 ± 10.6 | 122.0 ± 6.7 | 125.4 ± 9.3 | 102.3 ± 1.5 | 113.2 ± 11.8 | 126.0 ± 8.1* | 128.1 ± 5.8* |

| RBC count (x1012/L) | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.3* | 7.7 ± 0.7* | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.5* | 8.1 ± 0.4* |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.0 ± 3.0 | 37.0 ± 4.0 | 39.0 ± 1.0 | 40.0 ± 4.0 | 34.7 ± 1.2 | 38.0 ± 4.1 | 41.2 ± 1.7* | 41.1 ± 1.5* |

| MCV (fl) | 41.2 ± 2.4 | 41.3 ± 2.6 | 52.2 ± 1.0* | 52.2 ± 0.9* | 40.5 ± 2.2 | 42.8 ± 4.2 | 52.3 ± 1.1* | 51.1 ± 0.9* |

| MCH (pg) | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 12.4 ± 0.7 | 16.2 ± 0.4* | 16.3 ± 0.9* | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 12.8 ± 1.2 | 16.0 ± 0.1* | 15.9 ± 0.2* |

| MCHC (g/L) | 299.4 ± 9.5 | 302.0 ± 6.2 | 310.8 ± 10.9 | 313.0 ± 19.9 | 294.7 ± 3.5 | 298.8 ± 7.1 | 306.8 ± 7.4* | 310.9 ± 5.6 |

| RDW (%) | 22.5 ± 2.7 | 21.9 ± 1.6 | 16.4 ± 1.1* | 16.3 ± 1.0* | 22.3 ± 1.0 | 22.1 ± 1.7 | 15.9 ± 0.2* | 15.9 ± 1.2* |

There are no significant differences in any of these parameters between wild type and knockout mice, or between males and females on any diet. *represents significant differences between low iron and normal diets within genders and genotypes. Data expressed as mean ± s.d.; n = 3–8. RBC; red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean cell hemoglobin; MCHC, mean cell hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Ndfip2 maintains iron homeostasis in female mice by regulating DMT1 in the liver

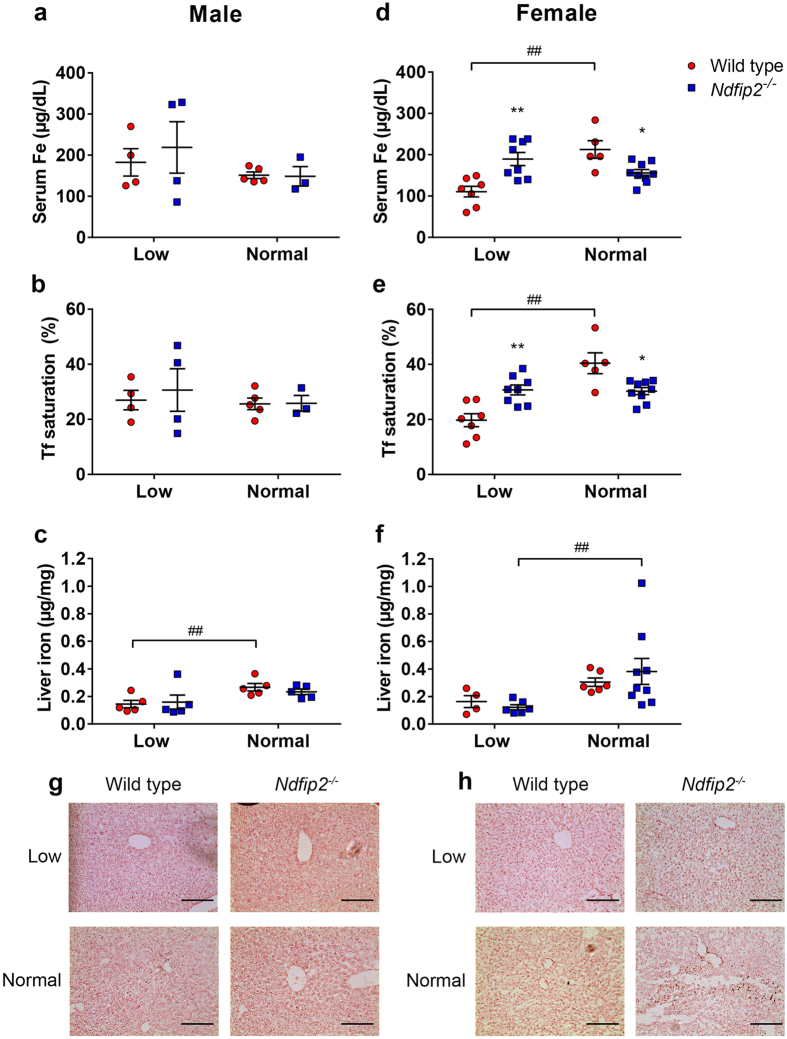

To assess the effect of Ndfip2 on iron transport and storage, we measured serum iron and transferrin saturation, as well as iron levels in the liver. In male mice, there were no significant differences between the normal and low iron diet in serum iron or transferrin saturation in either the WT or Ndfip2−/− mice (Fig. 3a,b). Liver iron levels were significantly decreased in male WT mice when fed a low iron diet, but Ndfip2−/− mice show no such effect (Fig. 3c). Female WT mice showed a significant decrease in serum iron and transferrin saturation when fed a low iron diet, while the Ndfip2−/− mice showed no significant decrease (Fig. 3d,e). Further to this, when fed a low iron diet, female WT mice showed no change in liver iron levels, but liver iron levels increased in female Ndfip2−/−mice on a normal diet (Fig. 3f). Differences in liver iron levels were confirmed by Perl’s staining in liver sections, which demonstrated that male mice have very little iron deposition in the liver regardless of dietary iron levels (Fig. 3g), whereas female Ndfip2−/−mice on a normal diet show increased liver iron staining compared to WT mice (Fig. 3h).

Figure 3. Sex-specific changes in serum iron, transferrin saturation and liver iron measurements in mice fed a low or normal iron diet.

(a,d) Serum iron levels and (b,e) transferrin (Tf) saturation in male and female wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice fed a normal or low iron diet. Male mice show no significant differences in serum iron or Tf saturation between normal and low iron diet in either wild type or knockout mice. Wild type female mice show a significant decrease in serum iron (##p < 0.0001) and Tf saturation (##p < 0.0001) when fed a low iron diet, but Ndfip2−/−females are able to maintain their levels when challenged. *represents a significant difference in serum iron (p = 0.0232) and Tf saturation (p = 0.008) between wild type and knockout females fed a normal diet. **represents a significant difference in serum iron (p = 0.0008) and Tf saturation (p = 0.0021) between wild type and knockout females fed a low iron diet. (c,f) Liver iron levels in wild type and Ndfip2−/−mice fed a normal or low iron diet. Wild type males show a significant reduction in liver iron levels when fed a low iron diet (##p = 0.0425), but Ndfip2−/−males are able to maintain liver iron levels. Ndfip2−/− females show a decrease in liver iron levels (##p = 0.0276). Red circles, wild type; blue squares, Ndfip2−/−. Data represent mean ± s.e.m.; n = 4–8. (g) Liver iron levels in male and (h) female mice as measured by Perl’s Prussian blue staining. Ndfip2−/− female mice fed a normal diet show significant iron deposits compared to wild type mice, and male mice do not show any significant staining.

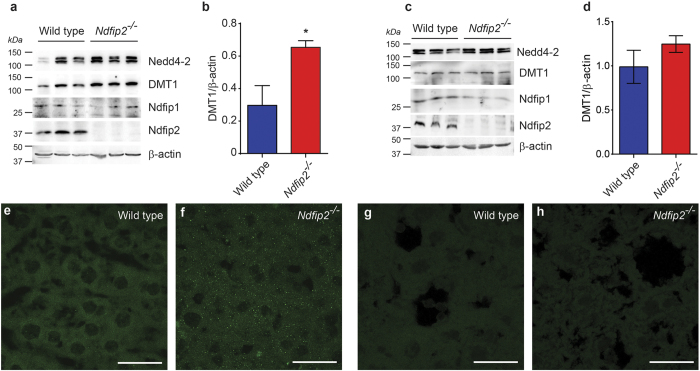

Since Ndfip2 did not appear to be required for DMT1 regulation in the duodenum, but seemed to modulate liver iron levels, we next assessed DMT1 regulation in the liver. Total DMT1 levels were increased in liver lysates of female Ndfip2−/−mice (Fig. 4a, quantitation in Fig. 4b) but not in male mice (Fig. 4c, quantitation in Fig. 4d), and liver sections from female Ndfip2−/−mice showed an increase in DMT1-labelled puncta compared to WT (Fig. 4e,f), with no change in male mice (Fig. 4g,h), suggesting that Ndfip2 is important for DMT1 regulation in the liver in female mice.

Figure 4. DMT1 expression is increased in the liver of female Ndfip2−/−mice, and there is no compensation for loss of Ndfip2 by Ndfip1 or Nedd4-2.

(a) Western blot showing levels of Ndfip1, Nedd4-2, DMT1 and Ndfip2 in female and (c) male liver protein lysates. There is no change seen in the levels of Ndfip1 or Nedd4-2 in Ndfip2−/− samples, indicating no compensation is occurring. DMT1 levels are increased in Ndfip2−/− female mice, but unchanged in male mice, suggesting that Ndfip2 is important for liver DMT1 regulation in females. β-actin acts as a loading control. (b,d) Quantitation of DMT1 expression relative to β-actin in liver samples from (a,c) showing significant upregualation of DMT1 in female Ndfip2−/− mice. Data expressed as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3), *p = 0.04. (e,f) DMT1 expression in liver sections from wild type and Ndfip2−/−female mice showing an increase in DMT1-positive puncta in the Ndfip2−/−liver. (g,h) DMT1 expression in liver sections from male mice showing no significant difference between wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice. Representative images of n = 4.

Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 share 52% sequence identity and 79% similarity15 and may function redundantly. It is also possible that Ndfip1 may be upregulated to compensate for the loss of Ndfip2. We therefore assessed the levels of Ndfip1 protein in liver lysates from WT and Ndfip2−/− male and female mice, and found that Ndfip1 levels were unaltered in the Ndfip2−/− mice (Fig. 4a,c). As Ndfips are known to recruit the Nedd4 family of ubiquitin ligases to regulate DMT18,16,17, we also checked the levels of Nedd4-2 but found no significant change (Fig. 4a,c).

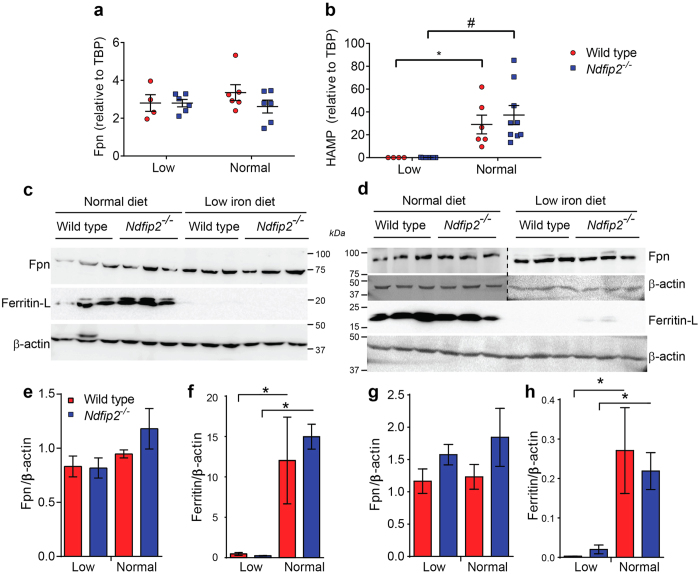

Ferroportin (Fpn) is the primary iron exporter in cells and is responsible for iron export from both enterocytes and hepatocytes2. Hepcidin is a small peptide produced by the liver in response to altered iron levels21, and ferritin complexes store excess iron molecules to inhibit their toxic effects and for release when required22. To determine whether Fpn, hepcidin or ferritin expression was altered in these mice, we measured mRNA and protein levels in livers from mice fed either a low iron or normal diet. While hepcidin responded as expected by decreasing under low iron conditions, neither Fpn nor hepcidin mRNA levels were significantly different between WT and Ndfip2−/−mice on either diet (Fig. 5a,b). Ferritin also responded as expected by decreasing in mice on a low iron diet, but both ferroportin and ferritin protein levels were unchanged between genotypes (Fig. 5c,d, quantitated in Fig. 5e–h).

Figure 5. Ferroportin, ferritin and hepcidin levels are unaffected by loss of Ndfip2.

(a) Ferroportin (Fpn) and (b) hepcidin (HAMP) mRNA levels expressed relative to TATA Box Binding Protein (TBP) are not significant between wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice fed either a low iron or normal diet. Hepcidin levels significantly decrease as expected in both the wild type and Ndfip2−/− mice fed a low iron diet (*p = 0.0402, #p = 0.0009). (c) Fpn and ferritin (light chain) protein levels in liver lysates from wild type and Ndfip2−/− female and (d) male mice showing no difference in expression between genotypes. The dotted line in d indicates that the right and left sides of the blots are from different gels. This is quantitated in (e–h) showing no significant difference between genotypes. *indicates significant differences in ferritin levels between diets as expected (p < 0.05). Red circles, wild type; blue squares, Ndfip2−/−. Data expressed as mean ± s.e.m, n = 4–9.

Discussion

Our previous work has demonstrated that Ndfip1 is an important regulator of DMT1 in mice16,18. To determine whether Ndfip2 is also necessary for DMT1 regulation, we performed the low iron feeding study using Ndfip2−/− mice. Unlike the Ndfip1−/− mice, Ndfip2−/− mice showed no significant difference in duodenal DMT1 expression or any of the hematological parameters measured; however, hepatic DMT1 levels were increased. In previous studies both Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 were found to interact with and ubiquitinate DMT1 in a heterologous in vitro system16, and Ndfip1 was found to be important for DMT1 regulation primarily in the duodenum, but also in the liver18. The results reported here suggest that Ndfip2 is dispensable for duodenal DMT1 regulation, but it may be required for liver DMT1 regulation. Both Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 are expressed in the liver (Fig. 4), but the predominance of Ndfip2 expression over Ndfip1 may, at least in part, explain why Ndfip2 appears to be the main regulator in the liver. DMT1 has four major isoforms, differing at both the 5’ and 3’ termini (designated 1A/B and ±IRE, respectively)8. These isoforms are differentially expressed in various tissues, with the 1A/+IRE isoform being predominant in the duodenum8, and the 1B isoforms being the major ones in the liver3,23. It is possible that Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 regulate alternative isoforms, which gives rise to their apparent tissue-specific functions. Further studies would be required to test this hypothesis.

Interestingly, on low iron diet Ndfip2−/− female mice were able to maintain steady serum iron levels and transferrin saturation, whereas WT mice showed a reduction in these parameters; this was coupled with an increase in hepatic DMT1 expression in the Ndfip2−/− mice. Hepatic DMT1 is responsible for transporting iron from the endosome into the intracellular space, where it is then able to be either released into circulation or stored bound to ferritin24. The higher levels of DMT1 in the liver resulting from the loss of Ndfip2 actually place these mice at a competitive advantage over WT mice in that there is more available iron to be released (as indicated by the reduction in liver iron levels) to compensate for the reduction in iron taken up from the diet. The stronger phenotype in the females may reflect a possible increase in sensitivity to iron levels suggested by hematological data, both in our study (Table 1), and in work previously reported25. Earlier studies have also reported sex-specific changes in iron parameters in mice on both iron-deficient and iron overload diets26,27. The age of the mice used in this study may also account for the sex-dependent differences we observe, as changes in hematological parameters and tissue iron levels are potentially sex-dependent in young mice28,29. Nevertheless, our data suggest that Ndfip2 is playing a role in DMT1 regulation in the liver, which is highlighted in female mice possibly due to an inherent sensitivity to iron perturbation.

Male Ndfip2−/−mice seem to be able to maintain liver iron stores, unlike the WT males that show a decrease in liver iron. This may be due to alterations in iron recycling by macrophages, which has been shown to be affected in cells and mice lacking the DMT1 homologue Nramp130,31. It has also been suggested that both DMT1 and Nramp1 are necessary for the efficient recycling of iron by macrophages32. Therefore, if Ndfip2 is also a regulator of DMT1 in macrophages (including Kupffer cells in the liver), changes in iron recycling in Ndfip2−/− mice may explain the differences in liver iron stores. Indeed the increased iron deposition in the female Ndfip2−/− mice liver appears to be primarily in the Kupffer cells surrounding central veins (Fig. 3h). Further experiments to evaluate the effect of Ndfips on DMT1 and/or Nramp1 in macrophages and iron recycling would be a worthwhile avenue of future study.

In summary, this study suggests that Ndfip2 is involved in the regulation of DMT1 in vivo, and that while Ndfip1 and Ndfip2 function by the same mechanism of recruiting Nedd4 family ligases to ubiquitinate and degrade DMT1, due to their tissue-specific function, loss of Ndfip2 alleviates the phenotype associated with loss of dietary iron. This could have important consequences for the diagnosis and treatment of iron-deficiency anemia and other diseases associated with decrease iron uptake.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The Ndfip2 knockout mice were purchased from the European Mouse Mutant Archive (EMMA). These mice were generated in a C57B6NTac background. The line originated from EUCOMM embryonic stem cell clone HEPD0550_6_G09 (International strain name B6NTac;B6N-Ndfip2tm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu). This targeted mutation was created by the insertion of the L1L2_Bact_P cassette into position 105291701 of chromosome 14, which corresponds with intron 2 of the Ndfip2 gene. The L1L2-Bact_P cassette in composed of an artificial exon (En2), a splice acceptor site, and the lacZ and NeoR genes, flanked by FRT and LoxP sites. Without the presence of Flp or Cre recombinases, this insertion results in a ubiquitous knockout (Ndfip2−/−) mouse. Animals were rederived, bred and maintained in SA Pathology Animal Care Facility and the University of South Australia Reid Animal Facility.

For iron feeding experiments, animals were fed ad libitum on a standard (164 mg/kg iron) or low iron (15 mg/kg) rodent diet (Specialty Feeds, Australia) for 3 weeks immediately following weaning. The studies were performed on 6-week-old littermates. All animal studies were approved by the institutional animal ethics and biosafety committees at SA Pathology and the University of South Australia, and were carried out according to the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from tail or ear fragments and PCR was performed using the KAPA Mouse HotStart Genotyping Kit (Geneworks, Australia), according to manufacturer’s instructions. To genotype Ndfip2 mice, a common primer situated at the beginning of intron 2 was used for PCR with one reverse primer against the end of intron 2 and another found within the lacZ gene of the trapping cassette (Fig. 1a). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. This triplex reaction results in a WT band of 558 bp and a knockout band of 329 bp (Fig. 1b). The absence of Ndfip2 protein in the knockout mice was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1c).

Antibodies and reagents

Rabbit anti-DMT1 designed against the fourth extracellular loop of mouse DMT1 was a generous gift from Dr Michael Garrick (University at Buffalo, New York)33. The production and affinity purification of a rabbit polyclonal against recombinant Ndfip1, Nedd4-2 and Ndfip2 have been described previously14,15,34. Commercial antibodies and reagents were purchased from the following suppliers: Donkey anti-rabbit AlexaFluor-488 and calcein-AM (Life Technologies), rabbit polyclonals anti-ferritin (light chain) and anti-ferroportin (Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (clone AC-15; Sigma-Aldrich), donkey anti-rabbit HRP and ECL™ Plex goat anti-mouse Cy5 (GE Healthcare). ECL prime (GE Healthcare) was used as the detection reagent for immunoblotting.

Blood and serum analyses

Blood was collected via cardiac puncture and complete blood count was performed by the Department of Clinical Pathology, SA Pathology. Serum was separated from whole blood using a 0.8 ml Z serum Sep MiniCollect tube (Greiner bio-one, Austria) with centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. Serum iron and transferrin saturation were measured using a Randox Fe/UIBC kit according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy

1–2 cm of proximal duodenum was fixed in HistochoiceTM (ProSciTech) before being cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS and then embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound. 10 μm frozen sections were mounted on polysine slides, fixed with ice cold acetone for 10 min, air dried, then rehydrated with PBS. Sections were then blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS for 2 h at room temperature and then stained with rabbit anti-DMT1 overnight at 4 °C (1:500 in 5% skim milk in PBS). After washing in PBS, sections were incubated with rabbit AlexaFluor-488 (1:500) for 2 h, washed, counterstained with DAPI and mounted in ProLong Gold antifade (Invitrogen). Confocal images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope using a 40×/1.30 water differential interference contrast (DIC) M27 objective and digitized at a depth of 8 bits. The fluorescence was sequentially acquired for multiple channels to avoid emission spectral bleed-through.

Immunoblotting

Proteins transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane were immunoblotted with primary antibody diluted in TBST (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 19 mM Tris, 0.1% Tween-20) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody. Visualization of Cy5 signal was carried out on a Typhoon FLA biomolecular imager (GE Healthcare) and HRP signals were detected on an ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare). Blots were quantitated using ImageJ software35.

Enterocyte isolation and fluorescence quenching assay

Enterocytes from WT and Ndfip2−/− mice were isolated as previously described18. Briefly, the proximal duodenum was removed and flushed through then washed with solution A (1.5 mM KCl, 96 mM NaCl, 27 mM sodium citrate, 8 mM KH2PO4, 5.6 mM Na2HPO4). The duodenum was minced in an enzyme cocktail (333 U/mL collagenase, 2.5 U/mL elastase, 10 μg/mL DNAse) in Krebs Ringer solution (120 mM NaCl, 24 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid], 4.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2) and incubated while shaking at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were filtered through a 40 μm filter and washed twice in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% nonessential amino acids, 50 μM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 100 μM L-asparagine. To determine the relative transport activity of freshly isolated enterocytes, we used a fluorescence quenching assay as previously described16. Cells were loaded with 0.25 μM calcein-AM (Invitrogen) for 20 min at 37 °C in loading medium (DMEM supplemented with 20 mM HEPES). Cells were washed and resuspended in transport buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) and fluorescence was recorded using a BMG FLUOStar Optima microplate reader (excitation 485 nm, emission 520 nm). Readings were taken every 2 seconds for the first 20 seconds to achieve a baseline reading, then every 0.5 second after injection of CoCl2 (final concentration, 100 μM; pH 6.7) for 150 seconds. Transport activity was calculated as the rate of fluorescence quenching (slope) observed in a 1-min period after the injection of metal ions and is displayed relative to wild-type enterocytes.

Perl’s Prussian Blue staining with DAB intensification

Iron deposits in liver sections were visualised using the Perl’s Prussian Blue technique. Sections were rinsed in TBST, then incubated in methanol for 20 min, followed by incubation in Perl’s working solution (1% HCl, 2% potassium ferrocyanide) for 1 h. Staining was intensified using DAB peroxidase substrate kit with nickel chloride (Vector Laboratories, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Neutral red was used as a counterstain.

RNA isolation and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from liver tissue using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), and was reverse-transcribed with a High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosciences). qPCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene™ 3000 (Qiagen) using RT2 Real-Time SYBR® Green/ROX PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, using the following themocycler conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. Expression was normalized to TBP by the 2−ΔΔCt method using Rotor-Gene™ 6000 Software (v1.7, Qiagen) and Microsoft Excel software.

Tissue iron quantitation

Small pieces of liver tissue were dried for 24 h at 85 °C after which they were weighed and digested in 25% nitric acid in a glass tube at 65 °C for 16 h. The samples were then diluted to 1% nitric acid and analysed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) by the Australian Water Quality Centre at SA Water. Values were normalized to dry weight.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests or two-way ANOVAs with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons tests (Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism), with statistical significance determined as being p < 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Foot, N. J. et al. Ndfip2 is a potential regulator of the iron transporter DMT1 in the liver. Sci. Rep. 6, 24045; doi: 10.1038/srep24045 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Brown and Kelly Wicks at the SA Pathology animal care facility and Jessica Parken and Jayne Skinner at the Reid Animal Facility for help with animal care and maintenance. This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia grant (GNT1059393) and a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (GNT1103006) to SK.

Footnotes

Author Contributions N.J.F. and S.K. conceptualized the project and designed experiments; N.J.F. and K.G. performed experimental work; K.M. provided assistance with animal work; N.J.F. and S.K. analysed data and wrote the paper; all authors discussed results and commented on manuscript.

References

- Ganz T. & Nemeth E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 500–510 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick M. D. & Garrick L. M. Cellular iron transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1790, 309–325 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham R. M., Chua A. C., Herbison C. E., Olynyk J. K. & Trinder D. Liver iron transport. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 4725–4736 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iolascon A. et al. Microcytic anemia and hepatic iron overload in a child with compound heterozygous mutations in DMT1 (SCL11A2). Blood 107, 349–354 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mims M. P. et al. Identification of a human mutation of DMT1 in a patient with microcytic anemia and iron overload. Blood 105, 1337–1342 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming M. D. et al. Nramp2 is mutated in the anemic Belgrade (b) rat: evidence of a role for Nramp2 in endosomal iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1148–1153 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming M. D. et al. Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation in Nramp2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nat. Genet. 16, 383–386 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick M. D. et al. Isoform specific regulation of divalent metal (ion) transporter (DMT1) by proteasomal degradation. Biometals 25, 787–793 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGurn J. A., Hsu P. C. & Emr S. D. Ubiquitin and membrane protein turnover: from cradle to grave. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 231–259 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotin D. & Kumar S. Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 398–409 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotia A. B. et al. The role of individual Nedd4-2 (KIAA0439) WW domains in binding and regulating epithelial sodium channels. Faseb J. 17, 70–72 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K. F., Dinudom A., Cook D. I. & Kumar S. The Nedd4-like protein KIAA0439 is a potential regulator of the epithelial sodium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 8597–8601 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub O. et al. Regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by Nedd4 and ubiquitination. Kidney Int. 57, 809–815 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearwin-Whyatt L. M., Brown D. L., Wylie F. G., Stow J. L. & Kumar S. N4WBP5A (Ndfip2), a Nedd4-interacting protein, localizes to multivesicular bodies and the Golgi, and has a potential role in protein trafficking. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 3679–3689 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K. F., Shearwin-Whyatt L. M., Fotia A., Parton R. G. & Kumar S. N4WBP5, a potential target for ubiquitination by the Nedd4 family of proteins, is a novel Golgi-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9307–9317 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foot N. J. et al. Regulation of the divalent metal ion transporter DMT1 and iron homeostasis by a ubiquitin-dependent mechanism involving Ndfips and WWP2. Blood 112, 4268–4275 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howitt J. et al. Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) regulation by Ndfip1 prevents metal toxicity in human neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15489–15494 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foot N. J. et al. Ndfip1-deficient mice have impaired DMT1 regulation and iron homeostasis. Blood 117, 638–646 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W., Xu H., Du X., Jiang H. & Xie J. Ndfip1 attenuated 6-OHDA-induced iron accumulation via regulating the degradation of DMT1. Neurobiol. Aging. 36, 1183–1193 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver P. M. et al. Ndfip1 protein promotes the function of itch ubiquitin ligase to prevent T cell activation and T helper 2 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity 25, 929–940 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T. & Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1823, 1434–1443 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. C. The Ferritin-like superfamily: Evolution of the biological iron storeman from a rubrerythrin-like ancestor. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1800, 691–705 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert N. & Hentze M. W. Previously uncharacterized isoforms of divalent metal transporter (DMT)-1: implications for regulation and cellular function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12345–12350 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. J. & Frazer D. M. Hepatic iron metabolism. Semin. Liver Dis. 25, 420–432 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strzalkowska A. et al. Quantitative trait loci analysis for peripheral blood parameters in a (BALB/cW x C57BL/6J-Mpl (hlb219)/J) F(2) mice. Experimental animals/Japanese Association for Laboratory Animal Science 60, 405–416 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger E. L., Beard J. L. & Jones B. C. Iron regulation in C57BLI6 and DBA/2 mice subjected to iron overload. Nutritional neuroscience 10, 89–95 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L. et al. Systems genetic analysis of multivariate response to iron deficiency in mice. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 302, R1282–1296 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger H. G. & Kunstyr I. Gerontological data of C57BL/6J mice. II. Changes in blood cell counts in the course of natural aging. Journal of gerontology 31, 648–653 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn P. et al. Age-dependent and gender-specific changes in mouse tissue iron by strain. Experimental gerontology 44, 594–600 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soe-Lin S. et al. Nramp1 promotes efficient macrophage recycling of iron following erythrophagocytosis in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5960–5965 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soe-Lin S., Sheftel A. D., Wasyluk B. & Ponka P. Nramp1 equips macrophages for efficient iron recycling. Exp. Hematol. 36, 929–937 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soe-Lin S. et al. Both Nramp1 and DMT1 are necessary for efficient macrophage iron recycling. Exp. Hematol. 38, 609–617 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdo J. R. et al. Distribution of divalent metal transporter 1 and metal transport protein 1 in the normal and Belgrade rat. J. Neurosci. Res. 66, 1198–1207 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstas A. A. et al. Regulation of the epithelial sodium channel by N4WBP5A, a novel Nedd4/Nedd4-2-interacting protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29406–29416 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S. & Eliceiri K. W. NIH Imge to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.