Abstract

Background & objectives:

ATRX is a recessive X-linked intellectual deficiency (X-LID) gene causing predominately alpha-thalassaemia with a wide and clinically heterogeneous spectrum of intellectual deficiency syndromes. Although alpha-thalassaemia is commonly present, some patients do not express this sign despite the ATRX gene being altered. Most pathological mutations have been localized in two different major domains, the helicase and the plant homeo-domain (PHD)-like domain. In this study we examined a family of three males having an X-linked mental deficiency and developmental delay, and tried to establish a genetic diagnosis while discussing and comparing the phenotype of our patients to those reported in the literature.

Methods:

Three related males with intellectual deficiency underwent clinical investigations. We performed a karyotype analysis, CGH-array, linkage study, and X-exome sequencing in the index case to identify the genetic origin of this disorder. The X-inactivation study was carried out in the mother and Sanger sequencing was achieved in all family members to confirm the mutation.

Results:

A novel ATRX gene missense mutation (p.His2247Pro) was identified in a family of two uncles and their nephew manifesting intellectual deficiency and specific facial features without alpha-thalassaemia. The mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. It segregated with the pathological phenotype. The mother and her two daughters were found to be heterozygous.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The novel mutation c.6740A>C was identified within the ATRX gene helicase domain and confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the three affected males as well as in the mother and her two daughters. This mutation was predicted to be damaging and deleterious. The novel mutation segregated with the phenotype without alpha-thalassaemia and with non-skewed X chromosome.

Keywords: Alpha thalassaemia, ATRX, exome sequencing, intellectual deficiency, novel mutation, X inactivation

Alpha-thalassaemia X-linked intellectual disability (ATRX) syndrome first described in 19901, is a rare disorder and only about 170 cases have been reported worldwide2. Most mutations are gathered in the two major functional domains, the helicase and PHD (plant homeo domain)-like domain3 and are directly linked to ATRX syndrome which often occurs associated with intellectual deficiency, alpha thalassaemia, learning difficulties as well as characteristic facial appearances, hypotonia, and cryptorchidism4,5. However, infrequent protein c-terminal truncation mutations are constantly associated with severe urogenital defects6. The clinical spectrum has been protracted to involve phenotypes without alpha thalassaemia7, or display a mild mental disability8 with non-skewed X-inactivation. In this study, we examined a family with three affected males.

Here we report a novel missense mutation (c.6740A>C) identified by X exome sequencing in exon 31 within the helicase domain of the ATRX gene in a family of three affected males in two generations (two brothers and their nephew) with a typical family pedigree of X-linked inheritance pattern and a clinical phenotype marked with intellectual disability, language impairment, prognathism, hypotonia, anteverted nares, large forehead, hypertelorism, open mouth, and a behavioural disorder associated with stereotypy.

Material & Methods

This study was conducted in the department of Molecular Genetics, Medical Genetics Center, Necker Hospital, Paris, France, during 2005-2012. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Three males with severe intellectual deficiency were identified in two generations of the same family. The proband; patient II-4 (Fig. 1) was the third sibling. He had two non-affected sisters. He had been followed in the Medical Genetics Center in Necker University Hospital of Paris since 2005. He was evaluated at the age of four years with complaints of developmental delay and dysmorphism. Pregnancy was normal. Delivery was at 38 wk of amenorrhoea. His birth weight was 3.76 kg, height 51 cm and head circumference was 34 cm. The mother reported that her son had feeding difficulties. His first smile was at the age of two months, head holding at four months, walked at three years. Till the age seven, speech was absent, and he did not achieve the normal milestones for his age. His weight was 17 kg (-2SD), height 110 cm (-2SD), head circumference was normal. Dysmorphism (Fig. 2a-c) included a large forehead, hypertelorism, small nose, depressed nasal bridge, anteverted nares, tended upper lip and everted lower, an open mouth with drooling and a prognathism. He has severe hypotonia and stereotype movements. He was friendly, not aggressive and did not recognize his parents. He needed help to eat and wash. His tendon reflexes were normal. There was no hepatosplenomegaly, no urogenital abnormalities. Electrocardiogram (ECG) was normal and there were no seizures. However, electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed wide slow curve of waking and sleeping.

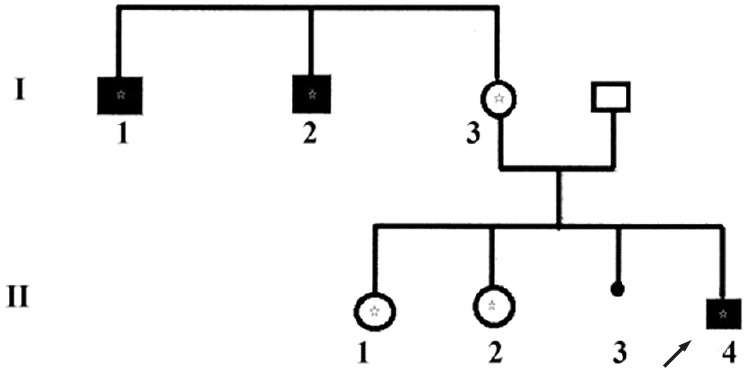

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of the family with related affected males. Black boxes indicate intellectual deficiency due to ATRX gene mutation. The asterik means that the subject carrys the mutation (c. 6740A>C) within the ATRX gene. In generation (I), three subjects carried the mutation. In generation (II) the index case is indicated by the arrow (II 4) and both sisters (II-1 and II-2) were heterozygous II-3 is an in utero foetal death (seven months of pregnancy).

Fig. 2.

Three photographs (a, b and c) of patient II-4, the images show the phenotype which involves a large forehead, hypertelorism, small nose, depressed nasal bridge, anteverted nares, tended upper lip and averted lower, an open mouth with drooling and a pragmatism.

His two maternal uncles (I-1, I-2), respectively 40 and 42 yr old) had a profound intellectual disability, speech was absent, at that age they were completely dependent upon others for personal care, they could eat alone, but needed help to wash. They were followed in an external center because of their age.

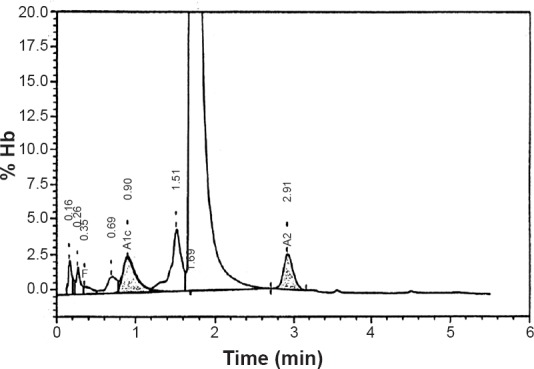

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed for the proband (patient II-3) and no abnormalities were found. Serum lactate and ammonia were normal. Iron and magnesium in serum were also normal, however, a slight anaemia was revealed in the index case (proband) and haemoglobin level was 11.5g/100ml with 80 fl of mean corpuscular volume (MCV) indicating microcytosis. Brilliant cresyl blue staining of red blood cells performed in index case did not reveal Heinz bodies (precipitated HbH). This result was subsequently confirmed by HPLC study (Bio-Rad VII Dual Instrument 4, California, USA) and there was no specific peak of haemoglobin H (Fig. 3). Haemoglobin A2 level was 2.6 per cent, HbF was 0.5 per cent and HbA was 96.9 per cent.

Fig. 3.

Elution haemoglobin chromatogram of patient II-3 specimen on Bio-Rad Variant V HPLC System. Time (min) represents the retention time in minutes for each fraction to elute; % Hb represents the percentage of haemoglobin in the elution peak. The retention time for each fraction is shown with the peak. HbA2 (2.6%) was eluted at a retention time of 2.91, HbF (0.5%) at a retention time of 0.35 min. The two earliest peaks of retention time 0.16 and 0.26 min correspond to HbA1a and HbA1b, respectively.

Genetic analysis: DNA was extracted from peripheral blood of all family members, excluding the father using the standard procedure of phenol chloroform method9. Purity and concentration were assessed by NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer V3-7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, USA). A high resolution karyotype and array-CGH (comparative genomic hybridization) were performed in patient II-3 which did not show any chromosomal anomaly. X-chromosome inactivation study was carried out in the mothers (I-3) according to the method of methylation-sensitive PCR and fragment-lenth analysis of androgen-receptor CAG repeat polymorphism10. Patient II-3 and his mother were then included in a next generation sequencing project for X-LID patients in our institute using SOLiD 5500 sequencer (Life technologies Grand Island, USA). DNA (5 μg for each patient) was enriched by micro droplet PCR procedure (Raindance technology, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) to target 11575 exons. Sorting and calling of SNP/InDel were performed using SAMTOOL and GATK softwares (Bioinformatic Programs, USA). Novelty was assessed by filtering the variants against a set of polymorphisms that are available in public databases such as dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), 1000 genomes (http://browser.1000genomes.org/in-dex.html), Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), and ExaC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). Only non-synonymous variants or changes affecting splice sites were analyzed. All sequence variants were prioritized by scoring phylogenetic conservation and functional impact (SIFT and Polyphen-2) and analyzed by Mutation Taster program (Charite-University Berlin, Germany, Europe). Candidate variants were selected and confirmed by Sanger sequencing11, using the 3500XL Genetic analyzer12 and the Big Dye cycle sequencing Kit of Applied Biosystem technology (Thermo-Fisher scientific, USA).

To sequence exon 31 of ATRX gene, forward (GGCTGGTGTTACATGTTTTGC) and revese (GCTGAAACCAACCCATAAAGA) primers were designed by Primer3 program (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) an online tool to design and analyze primers for PCR, and then were procured from Eurogentec (Belgium, Europe) in Belgium. X-chromosome inactivation study was carried out in the mother10 (Fig. 1).

Results & Discussion

Karyotypes of three patients (I-1, I-2 and II-4) were 46, XY. The high resolution karyotype and the CGH revealed no chromosome aberrations. Inactivation affected 60 and 40 per cent of X-chromosomes. Sequencing of X-exome from patient II-3 and his mother identified a single nucleotide substitution in exon 31 of the ATRX gene (Genbank accession number NG_008838) resulting in a substitution of an adenine (A) by a cytosine (c.6740A>C), and led to the substitution of a conserved histidine to a proline (p.His2247Pro). This mutation was not detected in any of the public databases (such as Exome Variant Server, 1000 genomes, dbSNP135) and in >200 X-exomes of index patients from other XLID familes. This mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the three affected males as well as in the mother and her two daughters. This mutation was predicted to be possibly damaging by polyphen-2 with a score of 0.906 (sensitivity: 0.82; specificity: 0.94). It was predicted to be deleterious by SIFT and could affect protein function with a score of 0.02. Predictions with MutationTaster were in favour of a disease causing variant.

There were three affected males in the two generations of the affected family. All females were healthy and heterozygous. Our linkage analysis (not shown) localized the morbid gene in a locus of the X-chromosome (Xq13.1-Xq21.1). The study of this region by Sanger sequencing did not cover the entire length of ATRX gene. Only N-terminal region was involved. The absence of clinical signs such as alpha-thalassaemia or urogenital abnormalities had deterred us from going further in ATRX gene exploration, and the C terminal region was not analysed.

Linkage study and Sanger sequencing are limited, tedious and often yield false negative results. Therefore, we performed a high throughput X exome sequencing of patient II-3 and his mother that revealed a new variant which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Exome sequencing based on next generation technique is a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery, revealing rare disease-related variants13. This technique revealed a substitution of an adenine by a cytosine (c.6740A>C) resulting in a novel missense mutation (p.His2247Pro). This mutation was found in all affected males, the mother and her two daughters who were heterozygous and asymptomatic. The mother X-chromosome inactivation pattern was not skewed. Heterozygous young sisters have a risk to transmit the genetic disorder to their offspring.

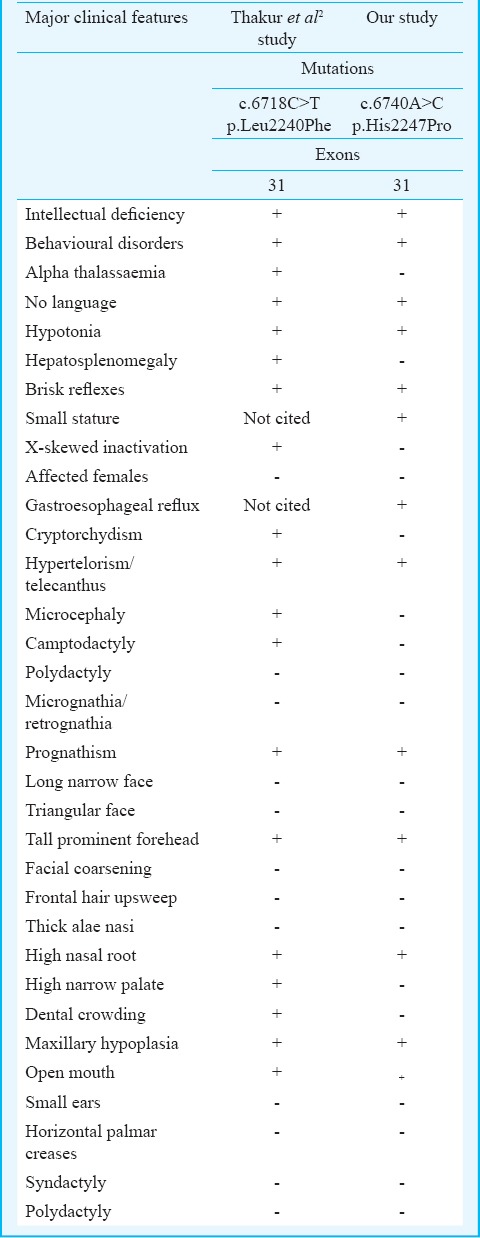

Clinical features of patient II-3 included intellectual deficiency, language delay, prognathism, a severe hypotonia, anteverted nares, large forehead, hypertelorism and a behaviour disorder associated with stereotypy. These signs largely overlap with those reported in ATRX related pathological mutations14 and those reported by Thakur et al2 who reported a missense mutation c.6718C>T(p.Leu2240Phe) related to the ATRX syndrome in the same exon and seven amino acids upstream the mutation similar to this study [c.6740A>C(p.His2247Pro)].

ATRX syndrome is mainly identified by intellectual deficiency, and alpha-thalassaemia8. Urogenital abnormality is a common presentation, however, it is not as common as alpha, thalassaemia15. Usually pathological mutations in the ATRX gene are associated with a large and clinically heterogeneous spectrum of X-linked mental deficiency syndromes16. However, with the advent of next generation sequencing, mutations have been identified resulting in less severe phenotypes lacking one or more of ATRX syndrome phenotypic features17. In this present study, the diagnosis of HbH performed in patient II-3 was based on the haemoglobin H inclusion body stain (brilliant cresyl blue) and the high performance liquid chromatography. The chromatograph showed no early peak at a retention time of less than one minute. Peaks at retention time 0.16 and 0.26 min represented HbA1a and HbA1b, respectively. The fractions HbA2 and HbF were normal.

In the literature, 90 missense/nonsense pathological mutations within the ATRX gene have been reported to date18. Four of them are located in exon 31 (p.Leu2240Phe, p.Ile2248Thr, p.His2254pro and p. Arg2271Gly). These are pathological and are related to ATRX syndrome. Our missense mutation (p.His2247Pro) is the fifth. It is a novel mutation which has not been reported until now. We identified it in exon 31 of ATRX gene, adjacent to the known pathological mutation (p.Ile2248Thr) described by Gibbons and colleagues6. They reported that the mutation was associated with intellectual deficiency as well as asplenia6. Moreover, Leahy and his team19 mentioned that the missense mutation (p.Arg2271Gly) in exon 31 was linked to the ATRX syndrome. The mutation (p.Leu2240Phe) reported by Thakur et al2 segregated with similar phenotype compared with our case (Table). Besides, ATRX alteration has been reported in intellectual disability, without thalassaemia16. Tarpey and colleagues20 have reported a case of mental deficiency syndrome without alpha-thalassaemia caused by the mutation (His>Pro) within the exon we studied but at a different position (p.His2254Pro). They described a mentally retarded case with behaviour disorder20.

Table.

Comparison of ATRX gene related disorders

In the present study, the new mutation was on an exon which belonged to helicase domain where approximately 41 per cent of ATRX syndrome causative mutations have been described3 and segregates with the pathological phenotype. We could suggest that the alteration of ATRX gene might have an effect on the phenotype of our patients and there could be a genotype-phenotype correlation, however, functional studies with additional cases and large number of affected families are required to confirm this finding.

The limitation of this study included the absence of ATRX protein function assessment. Proteomic study should be performed to better understand the effect of the mutation on the protein.

In conclusion, our study describes a novel missense mutation of the ATRX gene helicase domain, carried by three affected males of the two generations of the same family and segregated with intellectual deficiency, dysmorphism and behaviour disorder without alpha-thalassaemia and with non-skewed X-chromosome inactivation. The large heterogeneous clinical signs spectrum associated with ATRX mutations suggests that this gene has different modes of action in different tissues. Consequently, this novel mutation c.6740A>C may alter ATRX gene function and causes variable clinical features.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the Necker high throughput sequencing platform team for the technical support in performing X-exome sequencing. This work was supported by the Imaging Foundation (Necker Hospital) and INSERM institution Unity 781.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Wilkie AO, Zeitlin HC, Lindenbaum RH, Buckle VJ, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Chui DH, et al. Clinical features and molecular analysis of the alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndromes. II. Cases without detectable abnormality of the alpha globin complex. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:1127–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur S, Ishrie M, Saxena R, Danda S, Linda R, Viswabandya A, et al. ATR-X syndrome in two siblings with a novel mutation (c.6718C>T mutation in exon 31) Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:483–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badens C, Lacoste C, Philip N, Martini N, Courrier S, Giuliano F, et al. Mutations in PHD-like domain of the ATRX gene correlate with severe psychomotor impairment and severe urogenital abnormalities in patients with ATRX syndrome. Clin Genet. 2006;70:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latiff ZA, Omar SAS, Lau D, Wong SW. Alpha-thalassemia mental retardation syndrome: A case report of two affected siblings. J Pediatr Neurol. 2013;11:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbons RJ, McDowell TL, O’Rourke DM, Garrick D, Higgs DR. Mutations in ATRX, encoding a SWI/SNF-like protein, cause diverse changes in the pattern of DNA methylation. Nature Genet. 2000;24:368–71. doi: 10.1038/74191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbons RJ, Wada T, Fisher CA, Malik N, Traeger-Synodinos J. Mutations in the chromatin-associated protein ATRX. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:796–802. doi: 10.1002/humu.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villard L, Toutain A, Lossi AM, Gecz J, Houdayer C, Moraine C, et al. Splicing mutation in the ATR-X gene can lead to a dysmorphic mental retardation phenotype without alpha-thalassemia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:499–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yntema HG, Poppelaars FA, Derksen E, Oudakker AR, Roosmalen R, van Bokhoven H. Expanding phenotype of XNP mutations: Mild to moderate mental retardation. Am J Med Genet. 2002;110:243–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby KS. A new method for the isolation of ribonucleic acids from mammalian tissues. Biochem J. 1957;66:495–504. doi: 10.1042/bj0640405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubota T, Nonoyama S, Wakui K, Tonoki H, Masuno M, Imaizumi K, et al. A new assay for the analysis of X-chromosome inactivation based on methylation-specific PCR. Hum Genet. 1999;104:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s004390050909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouazzi H, Bouaziz S, Alwasiyah MK, Trujillo C, Munnich A. Non-syndromic X linked intellectual disability in two brothers with a novel NLGN4X gene splicing mutation (NC_018934.2: g. 1202C>A) J Case Rep Stud. 2015;3:6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouazzi H, Lesca G, Trujillo C, Alwasiyah MK, Munnich A. Nonsyndromic X-linked intellectual deficiency in three brothers with a novel MED12 missense mutation [c.5922G>T (p.Glu1974His)] Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:604–9. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Emond MJ, Nickerson DA, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:745–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abidi FE, Cardoso C, Lossi A-M, Lowry RB, Depetris D, Mattéi M-G, et al. Mutation in the 5’alternatively spliced region of the XNP/ATR-X gene causes Chudley-Lowry syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:176–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons R. Alpha thalassaemia-mental retardation, X linked. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen LR, Chen W, Moser B, Lipkowitz B, Schroeder C, Musante L, et al. Hybridisation-based resequencing of 17 X-linked intellectual disability genes in 135 patients reveals novel mutations in ATRX, SLC6A8 and PQBP. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:717–20. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basehore M, Michaelson CR, Levy-lahad R, Sismani C, Bird L, Friez MJ. Alpha-thalassemia intellectual disability: variable phenotypic expression among males with a recurrent nonsense mutation – c.109C>T (p.R37X) Clin Genet. 2015;87:461–6. doi: 10.1111/cge.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HGMD mutation result. [accessed on January 4, 2016]. Available from: http://hgmdtrial.biobase-internationalcom/hgmd/pro/everymut.php .

- 19.Leahy R, Philip R, Gibbons RJ, Fisher C, Suri M, Reardon W. Asplenia in ATR-X syndrome: a second report. Am J Med Genet. 2005;139:37–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarpey PS, Smith R, Pleasance E, Whibley A, Edkins S, Hardy C, et al. A systematic, large-scale resequencing screen of X-chromosome coding exons in mental retardation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:535–43. doi: 10.1038/ng.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]