Abstract

Background

Although hospitalizations due to invasive pneumococcal disease declined after routine immunization of young children with a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in 2000, information on trends in pneumococcal meningitis is limited.

Methods

We estimated national trends in pneumococcal meningitis hospitalization rates using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1994-2004. Pneumococcal meningitis cases and deaths were identified based on the ICD9-CM coded primary discharge diagnosis and rates were calculated using US Census data as denominators. Year 2000 was considered a transition year and average annual rates after PCV7 introduction (2001-2004) were compared with baseline years (1994-1999).

Results

During 1994-2004, there were 21,396 hospitalizations and 2,684 (12.5%) deaths from pneumococcal meningitis. In children aged <2 years, average annual rates of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations per 100,000 declined from 7.7 in 1994-1999 to 2.6 in 2001-2004 (% change: -66.0%; 95% CI: -73.5 to -56.3). Among children aged 2-4 years, rates declined from 0.9 to 0.5 per 100,000 (-51.5%; 95% CI: -66.9 to -28.9). Average rates also declined by 33.0% (95% CI: -43.4 to -20.9) among adults aged ≥65 years. In the four years after PCV7 introduction, an estimated 1,822 and 573 pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations were prevented in persons aged <5 and ≥65 years, respectively. An estimated 3,330 pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations and 394 deaths were prevented in persons of all ages.

Conclusion

Following implementation of routine childhood immunization with PCV7, hospitalizations for pneumococcal meningitis declined significantly in both children and adults. Most pneumococcal meningitis cases now occur in adult-age groups.

Keywords: Keywords: pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, meningitis, epidemiology

Background

After the introduction of conjugate vaccines to prevent Haemophilus influenzae type b disease, Streptococcus pneumoniae became the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in the US [1]. The risk of developing pneumococcal meningitis is highest among young children, older adults, persons with chronic illnesses, and immunocompromised individuals [1-3]. Even with advances in medical care, the case fatality ranges from16% to 37% in adults [4] and 1% to 2.6% in children [1, 5]. Those who survive the disease have a 30% to 52% risk of neurological sequelae [6, 7].

In 2000, a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was licensed and recommended for routine use in US children [3]. PCV7 prevented invasive pneumococcal diseases (e.g. bacteremia, meningitis) and reduced nasopharyngeal carriage of vaccine serotypes in clinical trials [8-10].

Studies have demonstrated declines in invasive pneumococcal disease in all age groups following the introduction of PCV7 [11-14]. However, by 2002-2003, the rates of pneumococcal meningitis in adults aged ≥50 years were reported not to have changed compared with baseline years [13]. The national impact of PCV7 immunization program on pneumococcal meningitis in all age groups is currently unknown. We evaluated trends in the incidence and mortality of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations during 1994-2004, using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest source of inpatient data available in the US.

Methods

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS)

The NIS contains data on hospital inpatient stays from states participating in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) [15]. The NIS contains patient-level clinical and resource utilization data, and provides information on 5 to 8 million hospitalizations per year from approximately 1,000 hospitals. These hospitals constitute a 20% sample of community hospitals in the US, including nonfederal short-term, general, and specialty hospitals. Participating hospitals are sampled by stratified probability sampling in five strata (ownership/control, bed size, teaching status, urban/rural, and US region), with sampling probabilities proportional to the number of US community hospitals in each stratum. The NIS collects data on all hospitalizations regardless of payment source and weighting and sampling variables are provided for each year to calculate national estimates.

Study Design

We evaluated the effect of implementation of PCV7 immunization on rates of pneumococcal meningitis, using an ecologic design. PCV7 was introduced in 2000 and vaccine coverage increased rapidly afterwards. Thus, calendar years were considered as a surrogate marker for vaccine uptake. NIS data from 1994-2004 were analyzed to allow the assessment of secular trends that preceded the implementation of the PCV7 vaccination program.

Definition of bacterial meningitis hospitalizations

A hospitalization due to pneumococcal meningitis was defined as a NIS record with a principal discharge diagnosis (first-listed diagnosis) of pneumococcal meningitis (International Classification of Diseases-Clinical Modification; Ninth Revision (ICD9-CM) code 320.1). In addition, we evaluated hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of streptococcal meningitis to examine the possibility that some cases of pneumococcal meningitis could have been misclassified as streptococcal meningitis (ICD9-CM code 320.2). We also evaluated rates of H. influenzae meningitis, which declined rapidly in early 1990s following routine childhood H. influenzae type b vaccine introduction and meningococcal meningitis, which has been reported to have gradually declined since the late 1990s [1, 16] [17]. Rates of other bacterial meningitis (specified or unspecified) were also evaluated for comparison. These five mutually exclusive diagnostic groups were aggregated into an all bacterial meningitis group.

A secondary analysis identifying meningitis codes listed in any diagnosis field (rather than principal diagnosis) yielded similar results as using only the primary diagnosis. Meningitis patients who died during their hospitalization were classified as meningitis deaths for the calculation of in-hospital mortality rates and case-fatality ratios.

Statistical analysis

National weighted frequencies of meningitis hospitalizations and their respective standard errors were calculated using NIS inflation (DISCWT) and stratum variables (NIS_STRATUM, STRATUM). Annual hospitalization rates were computed using NIS weighted frequencies as numerators and annual, mid-year population estimates from the US Census Bureau as denominators [18]. Similarly, national estimates of meningitis mortality rates were calculated using weighted in-hospital meningitis deaths as numerators and US Census mid-year population (person-year estimates) as denominators. We also evaluated trends in annual meningitis hospitalizations and mortality rates from 1994 to 2004 by age groups (<2, 2-4, 5-17, 18-39, 40-64, and ≥65 years).

In a separate analysis, we divided the study years into three time periods: 1994-1999 (baseline), 2000 (transition), and 2001-2004 (after PCV7 introduction). We considered year 2000 as a transition year and excluded it from this analysis because vaccine uptake started to increase substantially only after US Government purchasing through the Vaccines For Children program began in June 2000 [19].

To estimate the impact of the immunization program, we calculated the average weighted pneumococcal meningitis hospitalization and mortality rates for the baseline years (the reference group) and for the years following PCV7 introduction. Rate differences and percent changes were estimated by fitting outcome-specific Poisson regression models adjusting for age-group, calendar year and their interaction, while accounting for the NIS sampling design. The estimated population for each age-group during each calendar year was the offset term for the models. Comparisons of rates before and after the introduction of PCV7 were obtained through linear combinations of coefficients from the models [20, 21]. The number of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations and deaths prevented after PCV7 introduction was estimated by multiplying the estimated rate difference by the respective population estimates.

Since changes in rates of streptococcal meningitis in infants might be associated with changes in early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal infection, we performed a secondary analysis for this group excluding children aged <30 days.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS institute, Cary, NC) and Stata 8.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was determined not to require review by the institutional review boards of Vanderbilt University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Results

Of the total 395,917,007 weighted hospitalizations in the US during 1994-2004; 21,396 had a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumococcal meningitis. The median age of patients was 41 years (Interquartile range, IQR: 3-59) and 53% were male. The median length of hospital stay was 10 days (IQR: 6-14) and 2,684 (12.5%) pneumococcal meningitis patients died during their hospitalization.

Changes in pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations

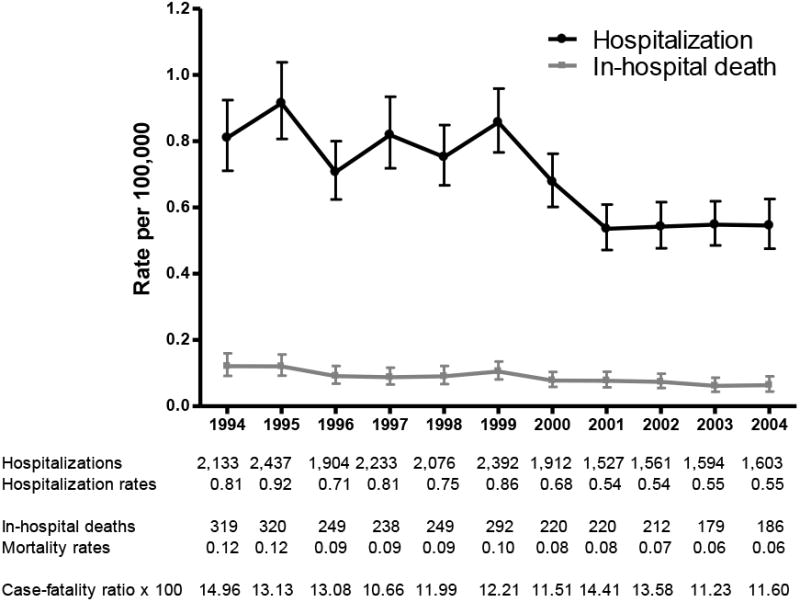

Annual rates of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations fluctuated before the introduction of PCV7 in 2000, declined sharply in 2000 and 2001 and remained relatively stable during 2002-2004. The pneumococcal meningitis mortality rates showed a similar pattern, whereas the overall case-fatality ratios fluctuated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trends in pneumococcal meningitis hospitalization, mortality rates and case-fatality ratios, US 1994-2004.

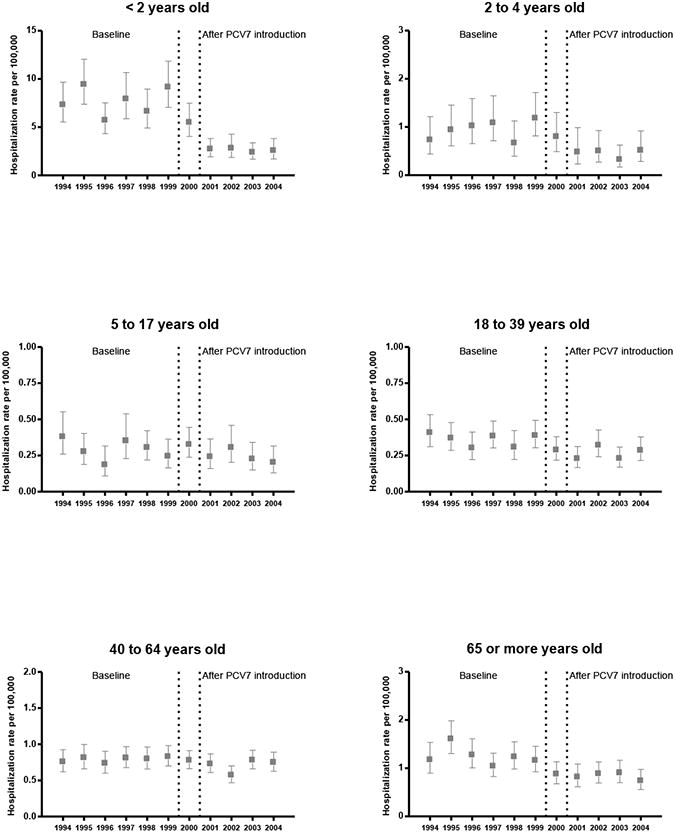

Overall, pneumococcal meningitis hospitalization rates declined by 33.0% after PCV7 introduction. The average annual rate in children aged <2 years decreased 66.0%, from 7.7 per 100,000 to 2.6 per 100,000 in this PCV7 target population. A 51.5% decline in annual rates was also observed in children aged 2-4 years. During the same period, the rates declined in older age groups as well. The average rates among persons aged ≥65 years decreased from 1.2 to 0.8 per 100,000, representing a 33.0% decrease (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1. Age-specific rates of pneumococcal and other bacterial meningitis-related hospitalizations, United States 1994-2004*.

| Baseline (1994-1999) | 95% CI | After PCV7 introduction (2001-2004) | 95% CI | Rate Difference | % Change | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumococcal meningitis | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 7.7 | (6.6, 8.9) | 2.6 | (2.1, 3.2) | -5.1 | -66 | (-73.5, -56.3) | <0.001 |

| 2 to 4 years | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.1) | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.6) | -0.4 | -51.5 | (-66.9, -28.9) | <0.001 |

| 5 to 17 years | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.3) | -0.1 | -15.9 | (-35.3, 9.5) | 0.198 |

| 18 to 39 years | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.4) | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.3) | -0.1 | -26.1 | (-38.8, -10.7) | 0.002 |

| 40 to 64 years | 0.8 | (0.7, 0.9) | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.8) | -0.1 | -10.5 | (-20.8, 1.1) | 0.075 |

| 65 or older | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.4) | 0.8 | (0.7, 1) | -0.4 | -33 | (-43.3, -20.9) | <0.001 |

| Total | 0.8 | (0.8, 0.9) | 0.5 | (0.5, 0.6) | -0.3 | -33 | (-38.9, -26.5) | <0.001 |

| Streptococcal meningitis | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 11.2 | (9.8, 12.6) | 6.6 | (5.6, 7.8) | -4.6 | -41 | (-51.3, -28.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 to 23 months | 8.3 | (7.3, 9.5) | 5.4 | (4.5, 6.5) | -2.9 | -34.9 | (-46.8, -20.3) | <0.001 |

| 2 to 4 years | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.7) | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.4) | -0.3 | -47.5 | (-66.3, -18.1) | 0.004 |

| 5 to 17 years | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0 | -4.7 | (-27.1, 24.5) | 0.722 |

| 18 to 39 years | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0 | 1.9 | (-16.6, 24.5) | 0.854 |

| 40 to 64 years | 0.6 | (0.5, 0.6) | 0.6 | (0.6, 0.7) | 0 | 11.3 | (-2.7, 27.3) | 0.119 |

| 65 or older | 0.9 | (0.8, 1) | 0.8 | (0.7, 0.9) | -0.1 | -12 | (-26.2, 4.8) | 0.152 |

| Total | 0.7 | (0.7, 0.8) | 0.6 | (0.6, 0.6) | -0.1 | -17.5 | (-24.8, -9.6) | <0.001 |

| Meningococcal meningitis | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 4.9 | (4.2, 5.7) | 2.2 | (1.8, 2.7) | -2.6 | -53.9 | (-63.7, -41.5) | <0.001 |

| 2 to 4 years | 1.5 | (1.3, 1.8) | 0.8 | (0.6, 1.0) | -0.7 | -46.9 | (-59.6, -30.1) | <0.001 |

| 5 to 17 years | 0.8 | (0.7, 1.0) | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.5) | -0.5 | -53.2 | (-63.1, -40.7) | <0.001 |

| 18 to 39 years | 0.5 | (0.4, 0.5) | 0.3 | (0.3, 0.4) | -0.1 | -29.2 | (-40.4, -15.8) | <0.001 |

| 40 to 64 years | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.2) | -0.1 | -31.4 | (-44.3, -15.5) | <0.001 |

| 65 or older | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.3) | 0.2 | (0.2, 0.3) | -0.1 | -23.2 | (-43.4, 4.3) | 0.091 |

| Total | 0.6 | (0.6, 0.7) | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.4) | -0.3 | -43.4 | (-49.8, -36.2) | <0.001 |

| Hemophilus influenzae meningitis | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 1.5 | (1.2, 1.9) | 0.8 | (0.6, 1.0) | -0.8 | -50.0 | (-65.0, -28.6) | <0.001 |

| 2 to 4 years | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.2) | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.3) | 0.0 | 39.9 | (-40.7, 229.9) | 0.444 |

| 5 to 17 years | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.1) | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 | -2.8 | (-50.4, 90.2) | 0.933 |

| 18 to 39 years | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 | 11.6 | (-34.8, 90.6) | 0.691 |

| 40 to 64 years | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.1) | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.1) | 0.0 | -11.2 | (-38.6, 28.4) | 0.528 |

| 65 or older | 0.2 | (0.1, 0.2) | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.2) | 0.0 | -22.7 | (-49.5, 18.3) | 0.236 |

| Total | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.1) | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.1) | 0.0 | -23.9 | (-37.5, 7.3) | 0.007 |

| Other bacterial meningitis | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 12.0 | (10.7, 13.5) | 9.0 | (7.8, 10.4) | -3.0 | -25.3 | (-37.3, -11.1) | 0.001 |

| 2 to 4 years | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) | 1.3 | (1.1, 1.6) | 0.1 | 10.6 | (-14.5, 43.0) | 0.442 |

| 5 to 17 years | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.8) | 0.8 | (0.7, 0.9) | 0.1 | 11.3 | (-6.0, 31.8) | 0.213 |

| 18 to 39 years | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.2) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.2) | 0.0 | -2.9 | (-13.8, 9.4) | 0.629 |

| 40 to 64 years | 1.3 | (1.2, 1.5) | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.5) | 0.0 | 1.1 | (-9.4, 12.9) | 0.844 |

| 65 or older | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.5) | 2.0 | (1.8, 2.2) | -0.3 | -13.3 | (-23.3, -2.1) | 0.022 |

| Total | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.6) | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | -0.1 | -6.8 | (-13.3, 0.1) | 0.055 |

| All bacterial meningitis** | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 37.2 | (33.4, 41.5) | 21.2 | (18.5, 24.2) | -16.1 | -43.1 | (-51.6, -33.2) | <0.001 |

| 2 to 4 years | 4.3 | (3.8, 4.7) | 3 | (2.6, 3.4) | -1.3 | -30.5 | (-41.4, -17.6) | <0.001 |

| 5 to 17 years | 2 | (1.9, 2.2) | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.8) | -0.4 | -20.4 | (-30.1, -9.3) | 0.001 |

| 18 to 39 years | 2.2 | (2.1, 2.3) | 1.9 | (1.8, 2.1) | -0.3 | -11.6 | (-18.9, -3.7) | 0.005 |

| 40 to 64 years | 3 | (2.9, 3.2) | 2.9 | (2.8, 3.1) | -0.1 | -3.2 | (-9.8, 4) | 0.373 |

| 65 or older | 4.9 | (4.6, 5.1) | 3.9 | (3.6, 4.2) | -0.9 | -19.4 | (-26.3, -11.8) | <0.001 |

| Total | 3.8 | (3.6, 4) | 3 | (2.9, 3.1) | -0.8 | -20.9 | (-25.6, -15.9) | <0.001 |

Rates are per 100,000 population

Encompasses pneumococcal, streptococcal, meningococcal, H. influenzae, and other bacterial meningitis

Pneumococcal meningitis, streptococcal meningitis, meningococcal meningitis, H. influenzae meningitis and other bacterial meningitis are mutually exclusive groups. The “other bacterial meningitis” group encompasses unspecified bacterial meningitis, staphylococcal meningitis, tuberculosis meningitis, and other specified and not elsewhere classified bacterial meningitis.

Figure 2. Trends in pneumococcal meningitis hospitalization rates by age group, US 1994-2004.

After implementation of routine immunization with PCV7, the overall pneumococcal meningitis mortality rate declined by 32.7% (Table 2). Children aged <2 years had the largest decline in mortality rates (from 0.4 to 0.2 per 100,000, a 51.1% decrease), followed by persons aged ≥65 years (from 0.3 to 0.2 per 100,000, a 43.9% decrease). As the decline in hospitalization rates was larger than the decline in mortality rates in children aged <2 years, the case-fatality ratio for pneumococcal meningitis (in-hospital deaths / meningitis hospitalizations) increased from 4.9 to 7.0 per 100. In persons aged ≥65 years, the case fatality ratio decreased from 27.2 to 22.8 per 100. There were no significant changes in mortality rates of pneumococcal meningitis in other age groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Age-specific rates of pneumococcal meningitis-related in-hospital deaths, United States, 1994-2004*.

| Pneumococcal meningitis in-hospital death | Baseline (1994-1999) | 95% CI | After PCV7 introduction (2001-2004) | 95% CI | Rate Difference | % Change | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 2 years | 0.37 | (0.25 - 0.55) | 0.18 | (0.1 - 0.32) | -0.19 | -51.1 | (-75.6, -2.2) | 0.043 |

| 2 to 17 years** | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.03) | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.04) | 0.01 | 41.1 | (-35.4, 208.1) | 0.388 |

| 18 to 39 years | 0.04 | (0.03 - 0.05) | 0.03 | (0.02 - 0.04) | -0.01 | -26.7 | (-56.9, 24.5) | 0.25 |

| 40 to 64 years | 0.11 | (0.09 - 0.14) | 0.08 | (0.06 - 0.11) | -0.03 | -27.2 | (-47.7, 1.4) | 0.06 |

| 65 or older | 0.34 | (0.28 - 0.41) | 0.19 | (0.15 - 0.25) | -0.15 | -43.9 | (-59.1, -22.9) | <0.001 |

| Total | 0.1 | (0.09, 0.11) | 0.07 | (0.06, 0.08) | -0.03 | -32.7 | (-44.7, -18) | <0.001 |

Rates are per 100,000 population

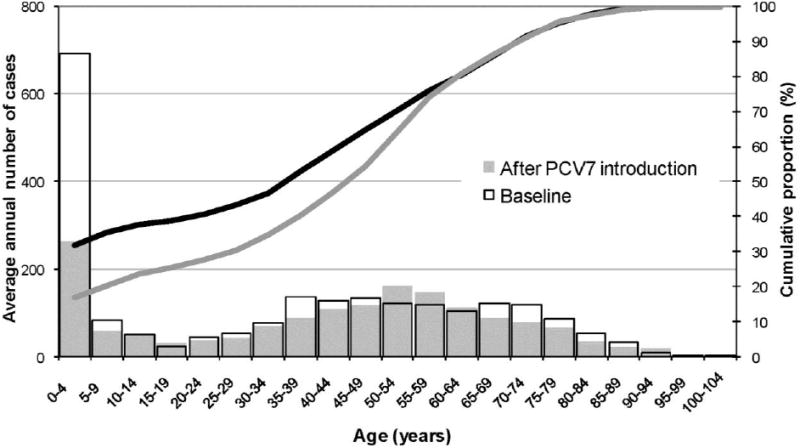

After introduction of PCV7, there was an average of 1,572 annual pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations compared with 2,199 during the baseline years. Based on the rate differences, we estimated that in the four years after PCV7 introduction 1,822, 360 and 573 pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations were prevented in persons aged <5, 18-39 and ≥65 years, respectively. In persons of all ages, there were 3,330 fewer pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations and 394 fewer deaths after PCV7 introduction compared with the baseline years. Because of these changes, the median age of patients increased from 37 (IQR: 1-59) years during the baseline years to 46 (IQR: 18-60) years after PCV7 introduction. During the baseline years, children aged <5 years accounted for 30% of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations compared with 15% after PCV7 introduction; the proportion of hospitalized meningitis patients aged ≥65 years (∼20%) remained constant throughout the study period (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Age distribution of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations before and after PCV7, US.

Footnote: Superimposed bars represent the average annual number of cases during baseline years and after PCV7 introduction. The average number of cases aged 50-64 and 90-94 years were higher after PCV7 introduction years than during baseline. Lines represent the respective cumulative distribution (as percent) by age intervals during baseline (dark line) and after PCV7 introduction (shaded line).

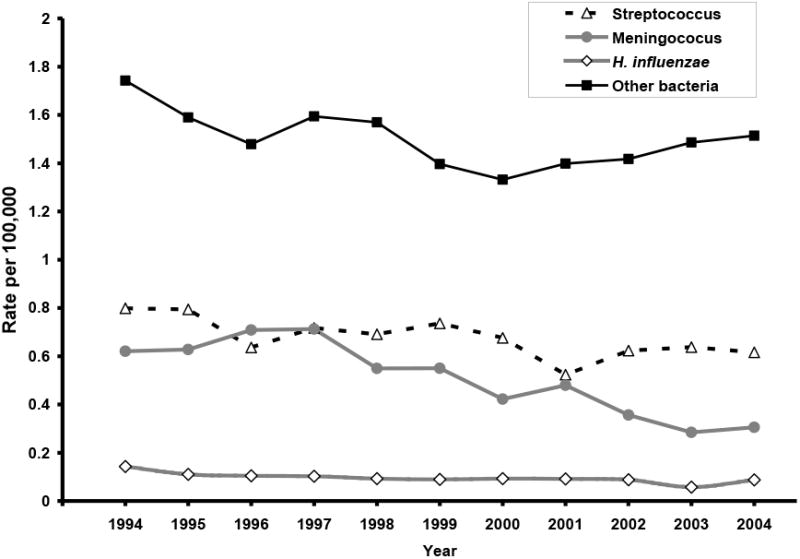

Changes in non-pneumococcal bacterial meningitis hospitalizations

Similar to the trends observed in pneumococcal meningitis rates, there was an overall 17.5% decrease in the rates of streptococcal meningitis. However, the decline was significant only in children aged <5 years. To assess the possible effect of changes in early onset-Group B Streptococcal meningitis on the estimates, we excluded children aged <30 days. The average rate of streptococcal meningitis hospitalizations in children aged 1-23 months showed a 34.9% reduction after PCV7 introduction (Table 1 and Figure 4).

Figure 4. Hospitalization rates for streptococcal, meningococcal, H. influenzae, and other bacterial meningitis, 1994-2004.

The overall rates of meningococcal and H. influenzae meningitis hospitalizations also declined during the study period (Table 1 and Figure 4). Rates of meningococcal meningitis decreased in all age groups, while the decline in H. influenzae meningitis rates occurred primarily in children aged <2 years. The declining trends in both meningococcal and H. influenzae meningitis rates began in the 1990s.

The other bacterial meningitis group included diagnoses for unspecified bacterial meningitis (54.3%), staphylococcal meningitis (11.2%), tuberculosis meningitis (9.1%), and other specified and not elsewhere classified bacterial meningitis (25.2%). During the study years, rates of other bacterial meningitis hospitalizations also decreased. Table 1 shows that children aged <2 years and 5 -17 years had the largest decreases in other bacterial meningitis hospitalizations over time. However, most of these decreases occurred in the 1990s; after 2000 the rates increased modestly (Figure 4).

Discussion

Following routine PCV7 immunization in the US, hospitalization rates for pneumococcal meningitis decreased significantly in young children, young adults, and elderly persons. We estimated that during the first four years after PCV7 introduction (2001-2004) about 1,800 meningitis hospitalizations in children aged <5 years were prevented, resulting in a major change in the age distribution of pneumococcal meningitis. The majority of cases now occur in working-age and older adults.

The 66% reduction observed in national rates of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations in children aged <2 years, the target population for the PCV7 program, is consistent with reports from other population-based studies of pneumococcal meningitis in selected areas including a 59% decline in children aged <2 years by 2001 in 7 geographic areas [12] and a 69% decrease in children aged <5 years by 2003 in Massachusetts [22]. Similarly, a 56% reduction in pneumococcal meningitis was observed between 1994 and 2004 in 8 children's hospitals in the US [23]. In addition, a 40% decrease of invasive pneumococcal disease was seen in infants aged 0 to 90 days after the introduction of PCV7 [14]. Laboratory-based surveillance in these investigations confirmed that the decline was limited to PCV7 serotypes, providing strong evidence for a causal association [12] [14] [22].

The NIS databases were large enough to detect significant declines in meningitis in adults and children as has been shown with all invasive pneumococcal disease [11, 12, 24]. Significant reductions in pneumococcal meningitis rates were seen in persons aged 18-39 years and ≥65 years, for whom PCV7 is not recommended. This suggests an indirect vaccine effect, likely due to reduced nasopharyngeal carriage of vaccine-type pneumococci in vaccinated children and decreased bacterial transmission to their close contacts [25]. Although use of highly active anti-retroviral therapies (HAART) has resulted in important declines in rates of invasive pneumococcal disease among HIV-infected adults [26], the major effect of HAART took place before PCV7 introduction [27].

The influence of increasing uptake of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) in persons aged ≥65 years during the study period on pneumococcal meningitis trends is unclear. The median national PPV23 coverage increased from 37% in 1995 to 60% in 2001, but has remained at similar levels since then. The declines in invasive pneumococcal disease documented after PCV7 introduction have been specific to serotypes included in PCV7 whereas no reduction was seen in the 16 serotypes contained only in PPV23 [11].

These observed declines have changed the epidemiology of pneumococcal meningitis in the US and as the age distribution of pneumococcal meningitis continues changing after implementation of PCV7, it might be necessary to re-evaluate prevalent pathogens and current age-based empiric treatment recommendations for bacterial meningitis [23]. Moreover, the mortality rates for pneumococcal meningitis declined after implementation of PCV7 vaccination and an estimated 394 deaths were prevented during the four years following PCV7 introduction. Nevertheless, despite the substantial vaccine effects and advances in treatment, the disease case-fatality remains high, emphasizing the need for additional prevention strategies.

In addition to the decline in pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations, we observed a comparable reduction in hospitalizations for streptococcal meningitis in children aged <5 years. Recommendations for giving peripartum antibiotics to mothers colonized with Group B Streptococcus were implemented before PCV7 and have resulted in a decline in early-onset (day 1-7) neonatal group B streptococcal meningitis [28]. The pattern of decline in streptococcal meningitis remained similar after children aged <30 days were excluded to account for the decline in early-onset neonatal Group B Streptococcal meningitis. Some observations suggest that this decrease in streptococcal meningitis might be partly due to misclassification of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis as “streptococcal meningitis”. First, the trend in streptococcal meningitis in children aged <2 years closely resembled that of pneumococcal meningitis in the same age group, showing a sharp decline in hospitalization rates soon after routine PCV7 immunization began (data not shown). Second, the reduction in streptococcal meningitis hospitalizations was significant only in children aged <5 years. If some of pneumococcal meningitis cases were misclassified as streptococcal meningitis, our estimate of the impact of PCV7 vaccine would be conservative. For children aged <2 years the decline in streptococcal meningitis represented an additional 864 fewer meningitis cases than expected after PCV7 introduction, compared to baseline years.

The hospitalization rates for meningococcal and H. influenzae meningitis also declined during the study period, beginning before the introduction of PCV7. The decline in meningococcal meningitis rates is consistent with the cyclical nature of this disease and with surveillance reports that have shown a decline in invasive Neisseria meningitidis disease since 1990s [17]. The quadrivalent A, C, Y, W-135 meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine has been used in military recruits and certain high risk groups since 1980s and in college freshmen since 2000 [29, 30]. The relation of this targeted vaccine use with the decline in disease rates, however, is unclear, particularly because use of this vaccine is restricted to persons aged >2 years and substantial declines were seen in this age group. H. influenzae meningitis declined following universal immunization of infants with H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in the late 1980s [31]. Rates for other bacterial meningitis decreased from 1994 to 2000, but increased after 2000. The temporal pattern of these changes was different from that of pneumococcal meningitis and there was no decline in hospitalizations for other bacterial meningitis overall across the study period.

Findings from this study need to be interpreted in light of some potential limitations. For this ecologic study, we did not have individual vaccination records and considered calendar year as a surrogate marker for PCV7 coverage in the population. However, the observed declines in pneumococcal meningitis were similar to the declines in invasive pneumococcal disease reported in other surveillance studies in selected geographic areas, [12, 14, 22] and consistent with rapidly increasing vaccine uptake after PCV7 introduction [19]. Immunization coverage with ≥3 doses increased to 68%, 73% and 83% for children born between February 2000-June 2002, February 2001-May 2003 and February 2002-July 2004, respectively [32], despite the reported intermittent vaccine shortages during 2001-2004 [33]. Moreover, in the absence of secular trends, the ecologic approach may be the preferred way to estimate the total program effect because it accounts for both direct and indirect vaccine effects.

We identified meningitis hospitalizations based on the ICD9-CM codes listed as primary discharge diagnoses, which are considered the main reasons for hospital admission [34] and are likely to be specific for a severe condition such as meningitis. Although rates of pneumococcal meningitis hospitalizations for children aged <2 years estimated from discharge data were similar in magnitude to those previously reported from active surveillance in selected US sites (10.3 cases per 100,000 during 1998-1999 and 4.2 per 100,000 in 2001) [13], NIS rates were somewhat lower suggesting lower sensitivity of this approach compared with active case finding.

Furthermore, although we explored information on rates preceding implementation of PCV7 to assess secular trends, we could not rule out effects on our estimates from increasing PPV23 uptake by the elderly population, meningitis outbreaks or abrupt changes in the coding of meningitis hospitalization. Nevertheless, outbreaks of pneumococcal meningitis are uncommon in developed countries and although changes in coding practices for meningitis during the study period are unknown, these changes would be unlikely to affect selectively different age groups.

Information on pneumococcal serotype distribution or antimicrobial susceptibility of the bacterial isolates is not available in the NIS. Before PCV7 introduction, vaccine serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 23F) accounted for 73% of pneumococcal meningitis in US children aged <6 before PCV7 [35]. Although invasive disease caused by these serotypes has been reduced dramatically, incidence of invasive disease caused by non-vaccine serotypes has been increasing in recent years [24, 36]. While to date these increases have been small compared with overall disease reductions [17], continuous monitoring of changes in serotype distribution is necessary.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive assessment of changes in pneumococcal meningitis hospitalization rates and age distribution of the disease, after routine PCV7 immunization program began in the US. Results from this study contribute to the evidence supporting the overall nationwide beneficial effects of PCV7 on pneumococcal meningitis, the most common cause of community-acquired bacterial meningitis.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was funded in part by the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement (TS-1392) and grant number 1R03 HS016784 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. Drs. Griffin and Grijalva reported receiving speaker honoraria from Wyeth. Other authors reported no conflicts.

References

- 1.Schuchat A, Robinson K, Wenger JD, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States in 1995. Active Surveillance Team. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997 Oct 2;337(14):970–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson KA, Baughman W, Rothrock G, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the United States, 1995-1998: Opportunities for prevention in the conjugate vaccine era. JAMA. 2001;285(13):1729–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR RecommRep. 2000;49(RR-9):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisfelt M, van de Beek D, Spanjaard L, Reitsma JB, de Gans J. Clinical features, complications, and outcome in adults with pneumococcal meningitis: a prospective case series. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(2):123–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddy RI, Perry K, Chacko CE, et al. Comparison of incidence of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae disease among children before and after introduction of conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005 Apr;24(4):320–3. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000157090.40719.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kastenbauer S, Pfister HW. Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: spectrum of complications and prognostic factors in a series of 87 cases. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 5):1015–25. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavez-Bueno S, McCracken GH., Jr Bacterial meningitis in children. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2005 Jun;52(3):795–810, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:187–95. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mbelle N, Huebner RE, Wasas AD, Kimura A, Chang I, Klugman KP. Immunogenicity and impact on nasopharyngeal carriage of a nonavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1999 Oct;180(4):1171–6. doi: 10.1086/315009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagan R, Melamed R, Muallem M, et al. Reduction of nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococci during the second year of life by a heptavalent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;174(6):1271–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease--United States, 1998-2003. MMWR MorbMortalWklyRep. 2005;54(36):893–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 1;348(18):1737–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lexau CA, Lynfield R, Danila R, et al. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among older adults in the era of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2043–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poehling KA, Talbot TR, Griffin MR, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among infants before and after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA. 2006 Apr 12;295(14):1668–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Healthcare cost and utilization project. Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient sample [Internet site] [Accessed October 30th 2006]; Available from http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- 16.Haemophilus b conjugate vaccines for prevention of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among infants and children two months of age and older. Recommendations of the immunization practices advisory committee (ACIP) Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports. 1991;40(RR-1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs). Surveillance reports [internet site] [Accessed October 30th 2007]; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/abcs/survreports.htm.

- 18.United States Census Bureau: Population Estimates Datasets [internet site] [Accessed October 30th 2007]; Available from http://www.census.gov/popest/datasets.html.

- 19.Nuorti JP, Martin SW, Smith P, Moran J, Schwartz B. Uptake of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among children in the 1998-2002 United States Birth Cohorts. Am J Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.028. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grijalva CG, Poehling KA, Nuorti JP, et al. National impact of universal childhood immunization with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on outpatient medical care visits in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006 Sep;118(3):865–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292(11):1333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu K, Pelton S, Karumuri S, Heisey-Grove D, Klein J. Population-based surveillance for childhood invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. PediatrInfect Dis J. 2005;24(1):17–23. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000148891.32134.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004 Nov 1;39(9):1267–84. doi: 10.1086/425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyaw MH, Lynfield R, Schaffner W, et al. Effect of introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006 Apr 6;354(14):1455–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dagan R, Givon-Lavi N, Fraser D, Lipsitch M, Siber GR, Kohberger R. Serum serotype-specific pneumococcal anticapsular immunoglobulin g concentrations after immunization with a 9-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine correlate with nasopharyngeal acquisition of pneumococcus. The journal of infectious diseases. 2005;192(3):367–76. doi: 10.1086/431679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Gelling L, Kool JL, Reingold AL, Vugia DJ. Epidemiologic relation between HIV and invasive pneumococcal disease in San Francisco County, California. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Feb 1;132(3):182–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heffernan RT, Barrett NL, Gallagher KM, et al. Declining incidence of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections among persons with AIDS in an era of highly active antiretroviral therapy, 1995-2000. JInfect Dis. 2005;191(12):2038–45. doi: 10.1086/430356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uy IP, D'Angio CT, Menegus M, Guillet R. Changes in early-onset group B beta hemolytic streptococcus disease with changing recommendations for prophylaxis. Journal of perinatology. 2002;22(7):516–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meningococcal disease and college students. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000 Jun 30;49(RR-7):13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prevention and control of meningococcal disease. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000 Jun 30;49(RR-7):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams WG, Deaver KA, Cochi SL, et al. Decline of childhood Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease in the Hib vaccine era. Jama. 1993 Jan 13;269(2):221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Immunization program. Coverage with individual vaccines and vaccination series. [Accessed October 30th. 2007]; internet site. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nip/coverage/NIS/05/toc-05.htm.

- 33.Smith PJ, Nuorti JP, Singleton JA, Zhao Z, Wolter KM. Effect of vaccine shortages on timeliness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: results from the 2001-2005 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):e1165–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Healthcare cost and utilization project. Hospital Inpatient Statistics, 1996 [Internet site] [Accessed October 20th. 2007]; Available from http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/natstats/his96/clinclas.htm.

- 35.Butler JC, Breiman RF, Lipman HB, Hofmann J, Facklam RR. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections among preschool children in the United States, 1978-1994: implications for development of a conjugate vaccine. JInfectDis. 1995;171(4):885–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hicks LA, Harrison LH, Flannery B, et al. Incidence of Pneumococcal Disease Due to Non-Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV7) Serotypes in the United States during the Era of Widespread PCV7 Vaccination, 1998-2004. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007 Nov 1;196(9):1346–54. doi: 10.1086/521626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]