Abstract

Background

The molecular events that drive the transformation from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have yet to be fully characterized. We hypothesized that detection of these mutations at the time of transformation from MDS to AML may lead to poorer outcomes.

Methods

We analyzed 102 MDS patients who were admitted to our institution between 2004 and 2013, had wild-type (wt) FLT3-ITD and RAS at diagnosis, progressed to AML, and had serial mutation testing at both the MDS and AML stages.

Results

We detected FLT3-ITD and/or RAS mutations in twenty-seven (26%) patients at the time of transformation to AML. Twenty-two patients (81%) had RAS mutations and five (19%) had FLT3-ITD mutations. The median survival after leukemia transformation in patients who had detectable RAS and/or FLT3-ITD mutations was 2·4 months compared to 7·5 months in patients who retained wt RAS and FLT3-ITD (hazard ratio [HR]: 3·08, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1·9–5·0, p < 0·0001). In multivariate analysis, FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations had independent prognostic significance for poor outcome.

Conclusions

We conclude that 26% of patients had detectable FLT3-ITD or RAS mutation at transformation to AML, and these mutations were associated with very poor outcome.

Keywords: MDS, AML, leukemic transformation, FLT3-ITD, RAS

1. Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a clinically and biologically heterogeneous group of disorders associated with ineffective hematopoiesis, abnormal differentiation, and cytopenias. Approximately one third of MDS patients progress to secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML).1 The transformation from MDS to sAML can be described as a genetic evolution that is characterized by the acquisition of key genetic abnormalities and clonal selection.2 The acquisition of additional cytogenetic abnormalities predicts both progression of MDS to sAML and poorer outcomes after transformation.3,4 More recently, next-generation sequencing has identified several recurrent genetic mutations that are associated with the dominant leukemic clone during progression from MDS to sAML (e.g., FLT3, NRAS, NPM1, RUNX-1, DNMT3A, and TP53).5–8 Similarly, studies have also reported clonal evolution and acquisition of new genetic mutations in MDS progressing to sAML or de novo AML relapsing after chemotherapy.2,9

FMS-like tyrosine kinase gene 3 (FLT3) internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations are rare in MDS, occurring at a frequency of 0·6–6%.10 They are more prevalent in AML, where they are detected in one third of AML patients.11–15 These mutations induce proliferation through constitutive tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and activation of the downstream STAT and RAS/MAPK pathways. Systematic evaluation of the occurrence of these mutations at the MDS stage and at the time of transformation to sAML has not been extensively studied.16

Similarly, activating mutations in the RAS proto-oncogene and its downstream signaling pathways are involved in uncontrolled growth factor-independent proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells.17,18 RAS mutant isoforms (mainly N-RAS) occur frequently in MDS as well as in AML.19–22 Although RAS mutation does not confer poor prognosis in de novo AML, its acquisition during MDS treatment correlates with disease progression and is suggestive of inferior outcome.8,16,23,24

Here, we sought to specifically assess the clinical implications of these mutations when detected at the time of leukemic transformation after loss of therapeutic response in MDS. We also evaluated the impact of the acquisition of additional cytogenetic abnormalities on clinical outcome and its correlation with the acquisition of FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations. We hypothesized that of the development of detectable levels of FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations at the time of transformation to sAML is associated with poorer prognosis.

2. Patients and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 102 MDS patients who were referred to our institution between 2004 and 2014 and had mutation testing at least once at the MDS stage and at the time of transformation to sAML. Diagnosis of MDS and AML was made according to World Health Organization criteria.25 We evaluated all 102 patients for the presence of detectable levels of FLT3-ITD and/or RAS mutations at the time of transformation to AML and assessed the effects of the presence of FLT3 and RAS mutations on survival outcome. Mutation assessment was performed prospectively as part of serial clinical molecular evaluation for these mutations at the MDS and AML stages.

We also characterized response durations and treatment failure in these patients. In this study, hypomethylating agent failure (HMA) was defined as either primary, when patients did not respond to HMA therapy, or secondary, when patients progressed after having initial response to HMA therapy.

This study was conducted following guidelines of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

2.1.2. FLT3 and RAS (NRAS and KRAS) mutation analysis

FLT3 mutation analysis was performed as described previously by Lin et al.26 Briefly, after the initial round of end-point PCR using fluorescently labeled primers, PCR products for wild-type and mutant FLT3 were detected using capillary gel electrophoresis-based sizing. The analytical sensitivity of this method is 1%. Mutation analysis for codons 12, 13, or 61 of NRAS or KRAS was performed using pyrosequencing during time period from 2004 to 2012. Later on, from 2012 onward, targeted next-generation sequencing27,28 was performed for detection of RAS mutations. Briefly, genomic DNA was harvested from bone marrow aspirates and amplified using previously described PCR primers. For pyrosequencing, the resultant samples were analyzed using gel electrophoresis to confirm amplification and then pyrosequenced using a Pyrosequencing PSQ96 HS System (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The sensitivity of this method is 5%. For next-generation sequencing, the harvested DNA was sequenced using TruSeq chemistry on a semi-custom or custom panel on a MiSeq (Illumina) following the manufacturers’ instructions and using previously described primers. The analytical sensitivity of this method is 2·5–5%. Overall, the analytical sensitivity of the pyrosequencing and NGS approaches were comparable for clinical use and reporting.

2.1.3. Cytogenetic analysis

Cytogenetic analysis was conducted in the Clinical Cytogenetics Laboratory at MD Anderson. Cytogenetic analyses were done on unstimulated bone marrow cells after 24–72 hours of culture, and G-banding analysis was performed according to standard techniques at our institution. For identification of abnormal clones, the international system for human cytogenetic nomenclature (ISCN 2005) was used.29 When possible, at least 20 metaphases were analyzed for each case. Three or more chromosomal abnormalities were defined as complex cytogenetics. Additional cytogenetic abnormalities were defined as structural change or gain in at least two metaphases or loss in three metaphases.

2.1.4. Statistical analysis

Patient and disease characteristics were compared using chi-square tests. Estimates of survival curves were calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier product limit method and compared by means of the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the relationship between patient characteristics and survival. Time to progression from MDS to sAML stage was calculated from time of referral to MD Anderson Cancer Center at the MDS stage to time of AML transformation. Predictive variables with p < 0·1 by univariate analysis were included in a multivariate analysis. All reported p values were 2-sided, and those less than 0·05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistical software for Windows (version 22·0).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics at MDS stage

Baseline characteristics at the time of MDS diagnosis are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 65 years (range, 26–83). Five (5%), 14 (14%), 24 (23%), 25 (24%), and 32 (31%) patients had revised international prognostic scoring system (IPSS-R)30 classifications of very low, low, intermediate (int), high, and very high-risk MDS, respectively (2 patients were not evaluable by IPSS-R). Twenty-two patients (22%) had therapy-related MDS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at MDS diagnosis (n= 102)

| Characteristic | Median [range], n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 [26–83] |

| WBC × 109/L | 2·8 [0·5–27·2] |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl), | 9·8 [5·5–14·2] |

| Platelet × 109/L | 77 [3–805] |

| Bone marrow blast % | 7 [0–19] |

| IPSS | |

| Low risk | 25 (25) |

| Intermediate-1 | 35 (34) |

| Intermediate-2 | 29 (28) |

| High risk | 13 (13) |

| IPSS-R*30 | |

| Very low | 5 (5) |

| Low | 14 (14) |

| Intermediate | 24 (23) |

| High | 25 (24) |

| Very high | 32 (31) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| Diploid | 45 (44) |

| −7/7q | 9 (9) |

| Complex (≥ 3 chromosomal abnormalities) | 20 (20) |

| Others | 31 (30) |

| t-MDS | 22 (22) |

| Initial therapy for MDS | |

| HMA-based therapy | 75 (73) |

| Immunomodulators | 7 (7) |

| Growth factors | 4 (4) |

| Other | 16 (16) |

| Stem cell transplant | 10 (10) |

| No. of therapies | 1 [0–4] |

WBC, white blood cell; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; R-IPSS, revised IPSS; t-MDS, therapy related MDS; HMA, hypomethylating agents; immunomodulators: lenalidomide and thalidomide; growth factors: erythropoietin and G-CSF

2 patients were not evaluable for R-IPSS scoring.

Seventy-three percent of patients progressed to AML after failing hypomethylating agent (HMA; azacitidine and decitabine)-based therapy. The remaining 27% of patients received immunomodulators such as lenalidomide, erythropoietin stimulating agents, and other therapies at the MDS stage.

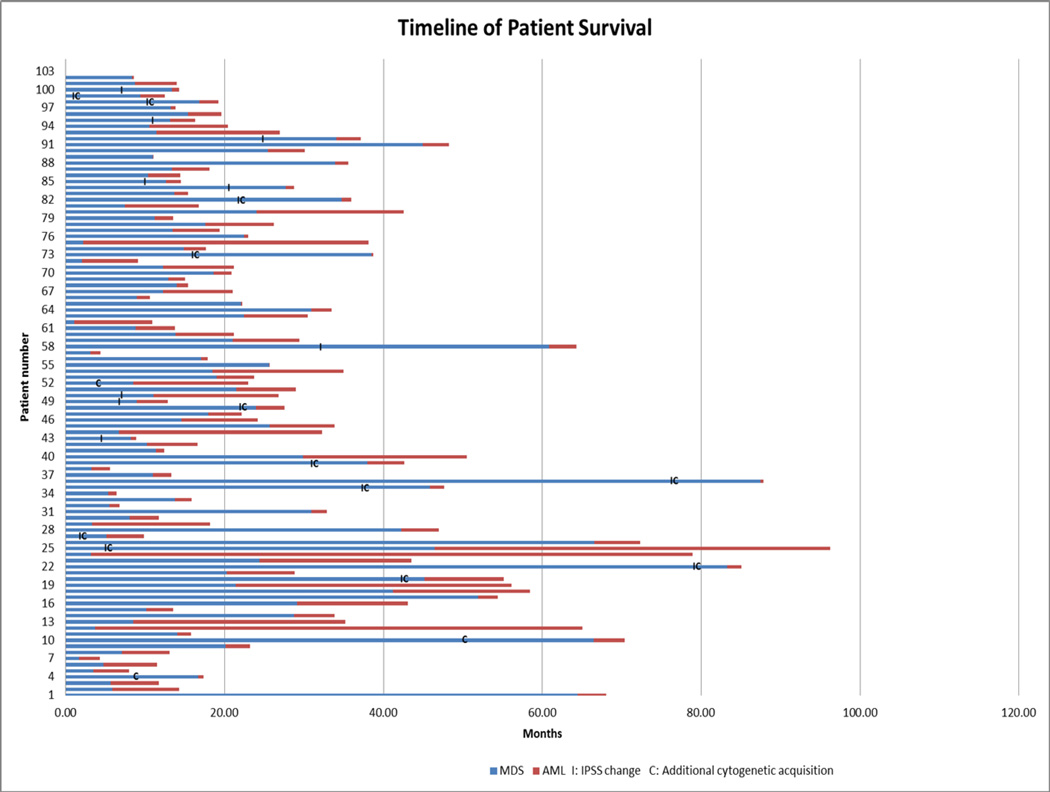

3.2 Progression from MDS to AML

Twenty-seven out of 102 patients (26%) who were negative for FLT3-ITD and RAS mutation at baseline acquired detectible FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations at the time of transformation to sAML. Among these patients, 22 (81%) had mutant RAS and five (19%) had mutant FLT3-ITD. Other mutations tested during the study period included NPM-1, CEBPA, c-KIT and JAK-2, but none of them were present at a detectable level at the time of transformation from MDS to sAML (data not shown). Overall, the median time to progression from MDS to sAML was 14 months (range, 1–87). The median time to progression from MDS to sAML was 21 months in patients who acquired RAS mutations, 15 months in those with FLT3-ITD mutations, and 13·5 months in those who retained wild-type FLT3-ITD/RAS at the time of sAML progression (p = 0·33). Detailed timelines of our patients’ disease courses can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Annotated timelines of patient disease course with documented changes in IPSS status and acquisition of additional cytogenetic alterations.

Overall, 52 (51%) patients acquired additional cytogenetic abnormalities4 from the time of MDS diagnosis to the time of progression to sAML. Among them, 14 patients (27%) acquired additional cytogenetic abnormalities at the MDS stage, and 37 patients (73%) acquired additional abnormalities at the time of progression to sAML. The median time to acquisition of additional abnormalities was 14 months (range, 1·7–80). Among patients with additional cytogenetic abnormalities, 23 patients (44%) had normal cytogenetics and 28 (56%) had abnormal cytogenetics at baseline. Thirty-six patients (69%) acquired poor-risk cytogenetics (inv (3), −7/del (7q), or complex [≥ 3 abnormalities]). Of the 27 patients who had detectable levels of FLT3-ITD or RAS mutation at the time of transformation, 13 (48%) patients acquired additional cytogenetic abnormalities. Among those patients, 8 (61%) acquired poor-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (Pearson r2 = 0·46, p = 0·6) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Acquisition of additional cytogenetic abnormalities from MDS diagnosis to AML transformation

| Median [range], n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS stage (n=14) |

AML stage (n= 37) |

Overall (n= 51) |

FLT3 ITD/RASm (n=13) |

|

| Time to acquisition (months) | 22 [2–80] | 13 [1·7–79] | 14 [1·7–79·5] | 16 [2–61] |

| No. of metaphases | 20 [2–20] | 12 [2–20] | 15 [2–20] | 20 [4–20] |

| ACA | ||||

| Complex (≥ 3 chromosomal abnormalities) | 5 (36) | 17 (46) | 22 (43) | 5 (38) |

| −7/ del (7q) | 5 (36) | 6 (16) | 11 (21) | 5 (38) |

| inv (3) (q21q26.2) | 1 (7) | 2 (5) | 3 (6) | 1 (8) |

| Trisomy 8 | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 4 (8) | 3 (23) |

| Miscellaneous | 3 (21) | 8 (22) | 11 (22) | 2 (16) |

MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ACA, additional chromosomal abnormalities, m; mutations

Among the 60 patients (59%) with low- or intermediate-1 (int-1)-risk IPSS scores at the time of MDS diagnosis, 26 (43%) advanced to int-2 or high-risk IPSS categories before their MDS eventually transformed to AML. In patients with low or int-1 IPSS scores at the time of MDS diagnosis, 19 (31%) had FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations at detectable levels at the time of transformation to AML. Only 6 of these patients (32%) transitioned to int-2 or high-risk IPSS before transformation to AML, and the other 13 patients progressed to AML without intermediate transition to int-2 or high-risk IPSS.

3.3. Baseline characteristics at AML stage

Baseline characteristics at the time of AML transformation are summarized in Table 3. The patients were divided into three groups: those with mutant RAS (n = 22), mutant FLT3-ITD (n = 5), and wild-type RAS and FLT3-ITD (n = 75). The median ages in the mutant RAS, mutant FLT3-ITD, and wild-type RAS/FLT3-ITD groups were 70, 60, and 66 years, respectively (p = 0·07). The patients who had detectable RAS or FLT3-ITD mutations had higher median WBC count and peripheral blast percentage (PB %) than those with wild-type RAS/FLT3-ITD (p < 0·001 and p = 0·04, respectively). No significant differences in baseline cytogenetics were observed in patients with detectable levels of FLT3-ITD and/or RAS mutations.

Table 3.

Characteristics at the time of transformation from MDS to AML

| Characteristics | Median [range], n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RASm (n = 22) |

FLT3-ITDm (n = 5) |

RAS wt / FLT3- ITD wt (n = 75) |

Overall (n= 102) |

P value | |

| Age | 70 [42–86] | 60 [53–66] | 66 [27–83] | 67 [27–86] | 0·07 |

| WBC × 109/L | 10 [0·5–88] | 11 [0·9–39.3] | 2 [0·3–184] | 2·6 [0·3–184] | ≤0·001 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 9 [7·2–11·3] | 9 [9–10·5] | 9 [5·8–12·7] | 9·3 [5·8–12·7] | 0·57 |

| Plt × 109/L | 31 [3–204] | 55 [16–82] | 27 [2–486] | 29 [2–486] | 0·77 |

| PB blast % | 14 [0–93] | 46 [14–96] | 5 [0–83] | 8 [0–96] | 0·04 |

| BM blast % | 37 [20–79] | 73 [49–82] | 35 [19–89] | 36 [19–89] | 0·06 |

| BM blast % ≥ 30 | 13 (59) | 4 (100) | 46 (61) | 63 (62) | 0·26 |

| Cytogenetics37 | |||||

| Intermediate | 8 (36) | 2 (50) | 38 (51) | 48 (47) | 0·62 |

| Poor | 14 (64) | 2 (50) | 37 (49) | 53 (52) | 0·47 |

| TTP to AML (months) | 21 [3–66] | 15 [5–38] | 13·5 [1–87] | 14 [1–87] | 0·33 |

| HMA failure at MDS stage | 12 (55) | 4 (80) | 58 (57) | 74 (72) | 0·08 |

| Ind. therapy for AML | 0·89 | ||||

| HDAC and anthracyclines | 4 (18) | 1 (20) | 15 (20) | 20 (20) | |

| HDAC + Ida + nucleoside analogues | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 5 (5) | |

| HDAC + nucleoside analogues | 1 (4) | 2 (40) | 12 (16) | 15 (15) | |

| HDAC + Ida + FLT3 inh | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| SDAC and anthracyclines | 2 (9) | 1 (20) | 5 (7) | 8 (8) | |

| SDAC + nucleoside analogues | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 8 (11) | 10 (10) | |

| HMA-based regimen | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 15 (20) | 18 (18) | |

| HMA + FLT3 inh | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Miscellaneous (inves. agents, targeted therapy) |

9 (40) | 0 (0) | 16 (21) | 25 (25) | |

| ≥2 therapies for AML | 10 (45) | 2 (50) | 37 (49) | 49 (48) | 0·87 |

| SCT | 2 (9) | 1 (25) | 15 (20) | 18 (18) | 0·48 |

RASm, RAS mutated; FLT3-ITDm, FLT3-ITD mutated; RAS wt/ FLT3-ITD wt, wild-type RAS and FLT3-ITD; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; Plt, platelet; PB blast%, peripheral blood blast percentage; BM Blast%, bone marrow blast percentage; TTP, time to progression; HMA, hypomethylating agents; HDAC, high-dose Ara-C (> 1gm/m2/day); SDAC, standard-dose Ara-C (200–500mg/m2/day); Invest, investigational; Ida, idarubicin; NA, nucleoside analogue (cladarabine, fludarabine, or clofarabine); FLT3 inh, FLT3 inhibitor; SCT, stem cell transplant.

3.4. Treatments and outcomes

Overall, 41 patients (40%) received high-dose Ara-C (HDAC; ≥ 1 gm/m2/dose) in combination with anthracycline, nucleoside analogues, or both during induction chemotherapy for AML. Eighteen patients (18%) had standard-dose Ara-C (SDAC; 200–500 mg/m2/day) in combination with anthracycline or nucleoside analogues. Another 43 patients (43%) received non-Ara-C-based induction regimens. Apart from one patient who received FLT3 inhibitor, none of the patients acquiring detectable FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations received targeted therapy, either because FLT3 inhibitors and therapy targeting RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK were not available during the time of the patient’s treatment or they were experimental agents in clinical trials and patients were not eligible. Some patients did not recieve standard induction chemotherapy (anthracycline or high-dose cytarabine) because their treating physician felt they were not candidates for intensive chemotherapy. However, there was no significant difference in the induction chemotherapy regimens patients received for wild-type or mutant RAS/FLT3-ITD sAML (Table 3).

The response rate (complete remission [CR] or complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery [CRi]) by mutational status and treatment type is summarized in Table 4. Overall, 27 patients (26%) achieved CR/CRi after induction chemotherapy. Six (27%), 2 (40%) and 19 patients (25%) achieved CR/CRi in the mutant RAS, mutant FLT3-ITD, and wild-type RAS/FLT3-ITD groups, respectively (p= 0·92). Generally, a higher proportion of patients (20 [66%]) achieved CR/CRi with Ara-C based chemotherapy (HDAC or SDAC) regimens than those receiving other regimens (7 [34%]; p= 0·07). The factors that influenced the decision not to treat patients with Ara-C-based regimens were mainly age, performance status, and co-morbidities.

Table 4.

Response rate to induction chemotherapy by mutation status and treatment

|

RASm (n=22) |

FLT3 ITDm (n=5) |

RAS wt/FLT3-ITD wt (n=75) |

Overall (n=102) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate (CR/CRi) | 6 (27) | 2 (40) | 19 (25) | 27 (26)a | ||||

| Treatment | N | CR/CRi | N | CR/CRi | N | CR/CRi | N | CR/CRib |

| HDAC combination | 7 (32) | 1 (14) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 32 (43) | 13 (40) | 42 (41) | 14 (33) |

| SDAC combination | 4 (18) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) | 1 (100) | 13 (17) | 4 (30) | 18 (18) | 6 (33) |

| HMA combination | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (100) | 14 (19) | 3 (21) | 18 (18) | 4 (22) |

|

Miscellaneous (inves. agents, targeted therapy) |

8 (36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (21) | 3 (19) | 24 (23) | 3 (12) |

RASm, RAS mutant; FLT3-ITDm, mutant FLT3-ITD; RAS wt/ FLT3-ITD wt, wild-type RAS and FLT3-ITD; HDAC, high-dose Ara-C (> 1 gm/m2/day); SDAC, standard-dose Ara-C (200–500 mg/m2/day); invest., investigational agents; HMA, hypomethylating agents; CR, complete remission; CRi, complete remission with incomplete count recovery.

P value= 0.92,

P value= 0.07

3.5. Survival

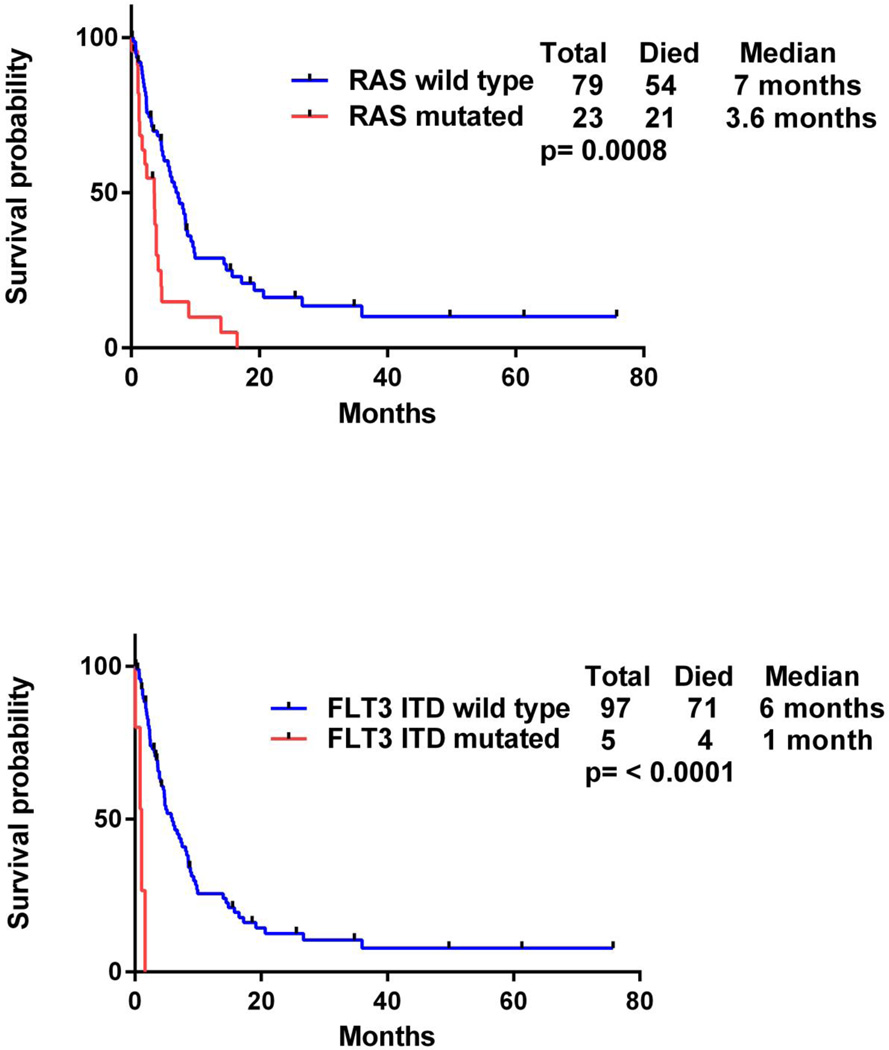

The median overall survival from the time of MDS diagnosis was 38·7 months in patients who acquired detectable levels of FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations at the time of transformation to AML compared to 23 months in patients who retained wild-type FLT3-ITD and RAS (p = 0·3). However, the median survival after leukemic transformation in patients with RAS mutation was 3·6 months compared to 7 months in patients with wild-type RAS (p = 0·0008) (Fig. 2). Moreover, patients with FLT3-ITD mutations had a median survival of 1 month after leukemic transformation compared to 6 months in patients with wild-type FLT3-ITD (p < 0·0001) (Fig. 2). When we compared patients with FLT3-ITD and/or RAS mutation to those with wild-type FLT3-ITD and RAS, the survival after leukemic transformation was 2·4 months in patients who acquired detectable levels of one of the mutations compared to 7·5 months in those who did not (p < 0·0001) (Fig. 3). In the subset of patients with poor-risk cytogenetics, those who acquired detectable levels of FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations had a median survival of 2·7 months after leukemic transformation compared to 6 months in patients with wild-type FLT3-ITD and RAS (p = 0·01) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Survival after leukemia transformation in mutated and wild-type RAS (top) and mutated and wild-type FLT3-ITD (bottom).

Figure 3.

Survival after leukemic transformation in mutated and wild-type FLT3-ITD and/or RAS (top) and in subset of patients with poor risk cytogenetics (bottom).

3.6. Univariate analysis for survival after AML transformation

Univariate analysis revealed that, besides having detectable levels of FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations, failure to respond to HMA at the MDS stage and subsequent progression to AML was predictive of inferior median survival, with a median survival of 4·7 months for patients who received HMA compared to 6·1 months for those who did not received HMA at MDS stage (hazard ratio [HR]: 1·54; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0·97–2·50; p = 0·07). Age greater than 60 years, therapy-related MDS/AML, and poor-risk cytogenetics did not influence survival outcome in this group of patients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate analysis for overall survival

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 60 | 1·31 | 0·777–2·16 | 0·32 |

| FLT3-ITDm at AML transformation | 5·60 | 2·10–15·76 | ≤ 0·001 |

| RASm at AML transformation | 2·44 | 1·80–6·72 | 0·0008 |

| Poor risk CG | 1·28 | 0·824–2·04 | 0·26 |

| Therapy related AML | 1·49 | 0·757–3·11 | 0·25 |

| HMA failure at MDS stage | 1·54 | 0·979–2·507 | 0·.07 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; m, mutated; CG, cytogenetics; HMA, hypomethylating agents; SCT, stem cell transplant

3.7. Multivariate analysis

Based on our selection criterion of p values < 0·1 in univariate analysis, 3 factors were used in subsequent multivariate analysis: FLT3-ITD mutation, RAS mutation, and failure to respond to HMA therapy. In the multivariate analysis, FLT3-ITD mutation (HR: 19·7; 95% CI: 5·95–65·66; p < 0·0001) and RAS mutation (HR: 2·7; 95% CI: 1·60–4·62; p 0·0002) retained their association with poor prognosis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis for overall survival

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLT3-ITDm at AML transformation | 19·77 | 5·95–65·66 | 0·000001 |

| RASm at AML transformation | 2·72 | 1·60–4·62 | 0·0002 |

| HMA failure | 1·383 | 0·79–2·40 | 0·25 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; m, mutated; HMA, hypomethylating agent; SCT, stem cell transplant

4. Discussion

The acquisition of detectable levels of FLT3-ITD and/or RAS mutation at the time of transformation occurred in approximately one third of patients and conferred extremely poor outcome in this cohort of patients. The median survival of 2·4 months after leukemic transformation in patients with RAS and/or FLT3-ITD-mutant AML was far inferior to that of patients with wild-type RAS and FLT3-ITD, who had a median survival of 7·5 months. After we adjusted for the prognostic effect of other covariates in multivariate analysis, FLT3-ITD and RAS mutation retained poor prognostic significance.

Several studies have previously reported the clinical implications of acquiring FLT3-ITD or RAS mutation in patients with MDS.8,14–16,24 Because those studies were specific to MDS, we sought to characterize how these mutations affected patient clinical outcomes specifically after leukemic transformation and did so by correlating clinicohematological features and mutational status at the time of progression to sAML. Our findings are consistent with earlier reports8,14 and revealed that the subset of patients with detectable levels of FLT3-ITD mutation had higher WBC and PB %. Additionally, we noted that the combined incidence of the RAS and FLT3-ITD mutations of 26% (RAS: 22%, FLT3-ITD: 4%) in our study varies somewhat from previous reports.15 This may be influenced by the nature of cases seen at our institution or by factors that may influence the decision to serially monitor patients for mutations.

Although patients who had detectable levels of FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations at the time of transformation to sAML had high WBC, peripheral blasts, and bone marrow blasts, the latency period from MDS to sAML was not shorter when we compared patients who acquired mutations to those who did not. In fact, the time to progression (TTP) from MDS to sAML was 21, 15, and 13·4 months in patients with RAS mutation, FLT3-ITD mutation, and wt RAS/FLT3-ITD, respectively (p = 0·33). These observations imply that these mutations may be late clonal events the occur near the time of transformation to sAML and might be triggered by the chemotherapy that the majority of patients received for MDS rather than simply a clonal expansion of existing undetectable mutant FLT3-ITD and RAS clones that were already present at the MDS stage. Similar observations were made by Ding et al in a population of relapsed AML. They demonstrated that after failing therapy, the patients acquired new mutations at relapse that were distinct from the mutation profile at diagnosis.9

The development of detectable levels of FLT3-ITD mutation at the time of AML transformation was predictive of extremely poor survival, with a median survival after leukemic transformation of 1 month in patients with FLT3-ITD mutation, and only 1 of these 5 patients survived more than 2 months after transformation. This survival outcome is worse than that reported for patients with primary FLT3-ITD-mutant AML.13,31 This inferior outcome might be due to the antecedent diagnosis of MDS in our study, which selects for a higher proportion of patients who had poor-risk disease by IPSS-R,30 therapy-related disease, and received multiple prior therapies, including HMA (azacitidine or decitabine). The dismal prognosis seen in these patients should be further investigated in large-scale prospective trials and demands better therapeutic strategies. Incorporating FLT3 inhibitors with induction chemotherapy and SCT in first remission might help to improve outcomes in this subset of patients.32,33

Twenty-two patients (23%) developed detectable levels of RAS mutation at the time of transformation to AML in our cohort. Earlier studies provided conflicting reports on the prognostic significance of RAS mutation detection, with a few finding positive impacts on survival and others reporting inferior outcomes.8,16,34,35 We found a strong correlation between newly detectable levels of RAS mutations at the time of progression to AML and poor survival, which was confirmed in a multivariate analysis. It is possible that RAS mutation in primary AML does not have any prognostic implications, whereas acquisition of these mutations at the time of transformation to AML does seem to have significant prognostic value in this subset of patients. This finding suggests that there may be opportunities for therapy targeting the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in this subset of patients.21,22,36

In contrast to earlier report by Jabbour et al4 that described poor prognosis associated with the acquisition of additional cytogenetic abnormalities in low-risk MDS at the time of transformation to sAML, acquisition of additional abnormalities did not influence overall survival in our patients, even in the subset of patients who acquired poor-risk cytogenetics. Overall 34 (33%) patients acquired poor-risk cytogenetics, either at the MDS stage or at the time of sAML transformation. Among them, 8 (24%) patients also acquired detectable FLT3-ITD/ RAS mutations (Pearson r2= 0·48, p = 0·6). This observation implies that there might be progressive genetic instability as the disease progresses, manifesting as acquisition of additional cytogenetics abnormalities and FLT3-ITD/RAS mutations. Although patients with poor-risk cytogenetics and wild-type FLT3-ITD/RAS did not have poor prognoses, the acquisition of detectable FLT3-ITD/RAS mutations in patients with poor-risk cytogenetics at the sAML stage resulted in worse survival outcomes. The clinical heterogeneity observed in patients with similar cytogenetic abnormalities with other somatic mutations has been previously reported by Bejar et al.5,10 Thus, existing risk groups may need to be redefined to include pertinent molecular markers as well as established high-risk clinical features.

There are some limitations associated with this study’s retrospective design. First, the methods we used to detect FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations might not be sensitive enough to detect small clones of these mutations at the time of MDS diagnosis. Thus, it remains unclear whether the acquisition of these mutations was directly involved in sAML transformation or whether the outgrowth of clones with these mutations at the time of transformation is the cause of the poor prognoses we observed. However, from a practical standpoint, very high-sensitivity sequencing modalities are not widely available, and our findings using more accessible techniques may help guide clinical practice. We specifically analyzed the prognostic significance of FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations because these are some of the most prevalent mutations as well as being genetic alterations for which targeted therapies are available. Future studies are needed to assess the prognostic impact of a broader range of genetic alterations, including NPM1, RUNX-1, DNMT3A, ASXL1 and TP53. Finally, in our study, apart from one patient with FLT3-ITD mutation, none received targeted therapy for FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations. The more recent availability of targeted therapies for these genetic lesions may likely affect outcomes for patients with FLT3-ITD or RAS mutations. Increasing awareness regarding the prognostic impact of FLT3 ITD and RAS mutations will hopefully change our future therapeutic strategies, which may include FLT3 inhibitors and drugs targeting RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK as a frontline therapy. These issues could be resolved by future prospective controlled studies and more sensitive methods of mutation detection, such as whole-genome sequencing.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a strong correlation between the acquisition of FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations and worse survival in sAML. This report also reinforces the importance of monitoring molecular markers in addition to more routine prognostic measures.

Acknowledgments

MC-C is funded by the Fundacion Alfonso Martin-Escudero. GGM is supported by the by MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016672. GGM is also supported by the Edward P. Evans Foundation, the Fundacion Ramon Areces, grant RP100202 from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), and by generous philanthropic contributions to MD Anderson’s MDS/AML Moon Shot Program. GGM partially supported by the Dr. Kenneth B. McCredie Chair in Clinical Leukemia Research endowment.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

TB, HK, and GGM designed research; TB, KPP, MC, and JC performed research; PAT, CD, GB, MK, ND, TK, EJJ, FR, RL, and GGM contributed patients; TB, SP, and MC analyzed data; and TB, ZB, and GGM wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, et al. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120(12):2454–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter MJ, Shen D, Ding L, et al. Clonal architecture of secondary acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1090–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haferlach C, Zenger M, Alpermann T, Schnittger S, Kern W, Haferlach T. Cytogenetic Clonal Evolution in MDS Is Associated with Shifts towards Unfavorable Karyotypes According to IPSS and Shorter Overall Survival: A Study on 988 MDS Patients Studied Sequentially by Chromosome Banding Analysis. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2011;118(21):968-. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabbour E, Takahashi K, Wang X, et al. Acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with IPSS defined lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome is associated with poor prognosis and transformation to acute myelogenous leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(10):831–837. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CY, Lin LI, Tang JL, et al. RUNX1 gene mutation in primary myelodysplastic syndrome--the mutation can be detected early at diagnosis or acquired during disease progression and is associated with poor outcome. Br J Haematol. 2007;139(3):405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai JL, Preudhomme C, Zandecki M, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia with 17p deletion. An entity characterized by specific dysgranulopoiesis and a high incidence of P53 mutations. Leukemia. 1995;9(3):370–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shih LY, Huang CF, Wang PN, et al. Acquisition of FLT3 or N-ras mutations is frequently associated with progression of myelodysplastic syndrome to acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18(3):466–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481(7382):506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bejar R, Stevenson KE, Caughey BA, et al. Validation of a prognostic model and the impact of mutations in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(27):3376–3382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daver N, Strati P, Jabbour E, et al. FLT3 mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(1):56–59. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99(12):4326–4335. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, et al. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2001;98(6):1752–1759. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgiou G, Karali V, Zouvelou C, et al. Serial determination of FLT3 mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome patients at diagnosis, follow up or acute myeloid leukaemia transformation: incidence and their prognostic significance. Br J Haematol. 2006;134(3):302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dicker F, Haferlach C, Sundermann J, et al. Mutation analysis for RUNX1, MLL-PTD, FLT3-ITD, NPM1 and NRAS in 269 patients with MDS or secondary AML. Leukemia. 2010;24(8):1528–1532. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi K, Jabbour E, Wang X, et al. Dynamic acquisition of FLT3 or RAS alterations drive a subset of patients with lower risk MDS to secondary AML. Leukemia. 2013;27(10):2081–2083. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49(17):4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coghlan DW, Morley AA, Matthews JP, Bishop JF. The incidence and prognostic significance of mutations in codon 13 of the N-ras gene in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1994;8(10):1682–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen JW, Steenvoorden AC, Lyons J, et al. RAS gene mutations in acute and chronic myelocytic leukemias, chronic myeloproliferative disorders, and myelodysplastic syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(24):9228–9232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borthakur G, Popplewell L, Boyiadzis M, et al. Phase I/II Trial of the MEK1/2 Inhibitor Trametinib (GSK1120212) in Relapsed/Refractory Myeloid Malignancies: Evidence of Activity in Patients with RAS Mutation-Positive Disease. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2012;120(21):677-. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain N, Curran E, Iyengar NM, et al. Phase II study of the oral MEK inhibitor selumetinib in advanced acute myelogenous leukemia: a University of Chicago phase II consortium trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(2):490–498. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacher U, Haferlach T, Kern W, Haferlach C, Schnittger S. A comparative study of molecular mutations in 381 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and in 4130 patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):744–752. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horiike S, Misawa S, Nakai H, et al. N-ras mutation and karyotypic evolution are closely associated with leukemic transformation in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 1994;8(8):1331–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin P, Jones D, Medeiros LJ, Chen W, Vega-Vazquez F, Luthra R. Activating FLT3 mutations are detectable in chronic and blast phase of chronic myeloproliferative disorders other than chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(4):530–533. doi: 10.1309/JT5BE2L1FGG8P8Y6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel KP, Ravandi F, Ma D, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with IDH1 or IDH2 mutation: frequency and clinicopathologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(1):35–45. doi: 10.1309/AJCPD7NR2RMNQDVF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luthra R, Patel KP, Reddy NG, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based multigene mutational screening for acute myeloid leukemia using MiSeq: applicability for diagnostics and disease monitoring. Haematologica. 2014;99(3):465–473. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.093765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaffer LG, Tommerup N. International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic N. ISCN 2005 : an international system for human cytogenetic nomenclature (2005) : recommendations of the International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Basel; Farmington, CT: Karger; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voso MT, Fenu S, Latagliata R, et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) predicts survival and leukemic evolution of myelodysplastic syndromes significantly better than IPSS and WHO Prognostic Scoring System: validation by the Gruppo Romano Mielodisplasie Italian Regional Database. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2671–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Breitruck J, et al. Prognostic significance of activating FLT3 mutations in younger adults (16 to 60 years) with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: a study of the AML Study Group Ulm. Blood. 2002;100(13):4372–4380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravandi F, Cortes JE, Jones D, et al. Phase I/II study of combination therapy with sorafenib, idarubicin, and cytarabine in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1856–1862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeZern AE, Sung A, Kim S, et al. Role of Allogeneic Transplantation for FLT3/ITD Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Outcomes from 133 Consecutive Newly Diagnosed Patients from a Single Institution. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplant. 17(9):1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Kali A, Quintas-Cardama A, Luthra R, et al. Prognostic impact of RAS mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(5):365–369. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadia TM, Kantarjian H, Kornblau S, et al. Clinical and proteomic characterization of acute myeloid leukemia with mutated RAS. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5550–5559. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, et al. A phase 1–2 study of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor, tipifarnib, combined with idarubicin and cytarabine for patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2011;117(6):1236–1244. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, et al. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children's Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood. 1998;92(7):2322–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]