Abstract

Drug releasing shape memory polymers (SMPs) were prepared from poly(thiourethane) networks that were coated with drug loaded nanogels through a UV initiated, surface mediated crosslinking reaction. Multifunctional thiol and isocyanate monomers were crosslinked through a step-growth mechanism to produce polymers with a homogeneous network structure that exhibited a sharp glass transition with 97% strain recovery and 96% shape fixity. Incorporating a small stoichiometric excess of thiol groups left pendant functionality for a surface coating reaction. Nanogels with diameter of approximately 10 nm bearing allyl and methacrylate groups were prepared separately via solution free radical polymerization. Coatings with thickness of 10–30 μm were formed via dip-coating and subsequent UV-initiated thiol-ene crosslinking between the SMP surface and the nanogel, and through inter-nanogel methacrylate homopolymerization. No significant change in mechanical properties or shape memory behavior was observed after the coating process, indicating that functional coatings can be integrated into an SMP without altering its original performance. Drug bioactivity was confirmed via in vitro culturing of human mesenchymal stem cells with SMPs coated with dexamethasone-loaded nanogels. This article offers a new strategy to independently tune multiple functions on a single polymeric device, and has broad application toward implantable, minimally invasive medical devices such as vascular stents and ocular shunts, where local drug release can greatly prolong device function.

Introduction

Shape memory polymers (SMPs) have broad interest as dynamic materials that can undergo pre-programmed transitions from temporary to permanent shapes upon application of a stimulus. SMPs are valuable as polymeric biomedical devices that can be implanted in a minimally invasive procedure and convert to a shape relevant to the final application due to their ability to assume complex geometries, and highly tunable chemistry that permits specific, predictable actuation1–4. A wide range of available polymer chemistries permits the design of materials that can respond to stimuli that are advantageous for actuation in physiological conditions such as temperature, water, and pH, as well as external stimuli that can enable on-demand shape changes such as light, ultrasound, and magnetic fields5–7. The mechanical properties of the SMP, particularly the modulus and toughness, are critical considerations for clinical implementation where the stiffness of an artificial material will ideally resemble that of native tissue to function effectively. Sufficient mechanical integrity may also be needed to prolong the implant lifetime, particularly in structural or load-bearing applications such as suture anchors and vascular stents8.

In addition to controlling mechanical properties and stimulus response, significant attention has been devoted to the development of multifunctional SMPs, particularly towards the addition of mechanisms for degradability and controlled drug release9. Several reports describe the combination of these functions for sustained, localized delivery of therapeutic agents and the eventual reduction of the SMP to biocompatible, nontoxic degradation products10–20. Triggered drug release from SMPs has also been achieved using ultrasound21–23, pH6, and photo-responsive24 materials. In all these cases the drug is loaded into and subsequently released from the bulk SMP, which in some cases could alter the network morphology and consequently interfere with shape recovery9. Furthermore, SMP processing methods can significantly change drug release characteristics25, which can lead to a discrepancy between the required mechanical properties of the SMP and the desired release profile. This served as motivation to develop a shape memory material in which a coating released the drug rather than the bulk matrix, allowing for two distinct but separate functions on the same polymeric device. Drug-releasing polymer coatings have been previously demonstrated to provide sustained, local release from medical devices using blends of linear polymers, layer-by-layer deposition of polyelectrolytes, and imbedded nanoparticles26–28, but have not been described for SMPs or other polymeric materials with specific mechanical functions. Here, we focus on developing coatings based on nanogels, which have controllable structure, chemical composition, and reactive group functionality29,30 that has led to application as drug delivery vehicles30,31 as well as polymer network components32–34.

Synthesizing functional materials from click reactions is a robust method of forming structurally and chemically well-defined polymers35. In particular, thiol-X reactions between thiols and electrophiles such as epoxides and isocyanates or thiol-Michael additions with electron deficient alkenes have been widely applied in organic synthesis and materials science due to rapid reaction rates in mild conditions and a large library of commercially available monomers36. Click reactions proceed through a step-growth crosslinking mechanism that results in a more homogeneous network structure compared to chain-growth crosslinking typically observed in (meth)acrylate homopolymerizations, for example, which is advantageous in creating SMPs with narrow glassy-to-rubbery thermal transitions. Photoinitiated thiol-ene polymerizations have been previously described as an efficient and versatile route for creating SMPs with excellent mechanical properties from a series of monomers with different backbone structures37. Networks formed from the thiol-isocyanate reaction replace the thioether bond formed in thiol-Michael networks with thiourethanes that can contribute increased toughness through strong hydrogen bonding38, which could be advantageous for creating new SMPs. However, the thiol-isocyanate reaction is traditionally extremely rapid with little to no temporal control, making processing and handling challenging39 and consequently has received less attention in the development of new functional materials. A recent study described a great improvement in controlling the onset of the thiol-isocyanate reaction by combining a phosphine and methanesulfonic acid to form an initiator/inhibitor “chemical clock” that can delay gelation by several minutes, which presents an opportunity for increased exploration into crosslinked thiourethane networks as functional materials40.

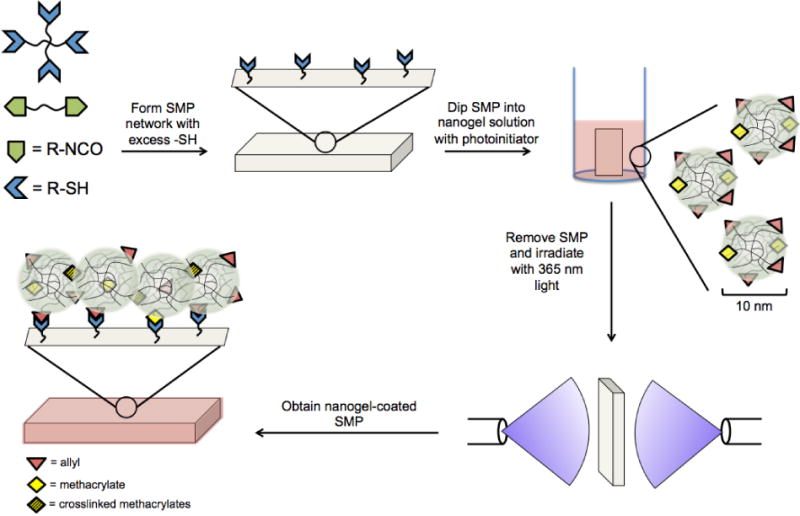

The orthogonality of click reactions allows for a high degree of control over functional group stoichiometry in the monomer formulations. If a stoichiometric excess of one component is added, then pendant functional groups will be available for post-polymerization modification. We hypothesized that thiourethane networks bearing excess thiol functionality could be designed from this straightforward method. Surface thiol functionality would then be available for a second click reaction with an alkene-functionalized nanogel to form the coating as diagrammed in Figure 1. In this study, an SMP was synthesized from hexamethylene diisocyanate (HMDI) and two multifunctional thiol monomers: pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP) and ethoxylated trimethylolpropane tri(3-mercaptopropionate) (ETTMP). Nanogels with mid- and chain-end hydroxyl groups were prepared from a solution free radical polymerization of poly(ethylene glycol) mono-methacrylate and dimethacrylate monomers and mercaptoethanol, which was followed by subsequent reaction with allyl isocyanate to form allyl-functionalized nanogels. Allyl groups were chosen since they participate in radical-mediated addition to thiols, while chain transfer to monomer discourages homopolymerization, enabling potentially uniform coating formation via a photoinitiated thiol-ene click reaction. Dexamethasone was chosen for the release studies, as it is a well-characterized and clinically relevant anti-inflammatory drug. The nanogel-based coating on an SMP, the subsequent effect on shape memory behavior, and release of a drug from the coating were investigated.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the process for fabricating nanogel-coated shape memory polymers (SMPs). Multifunctional thiol and isocyanate monomers are reacted to form networks with excess thiols based on control of initial functional group stoichiometry. The thiol-containing SMP is dip-coated in a solution of nanogels bearing pendant allyl and methacrylate groups and photoinitiator. The SMP is then exposed to 365 nm UV light for 60 s to initiate radical-mediated allyl-thiol and methacrylate-thiol crosslinking at the SMP surface and methacrylate-methacrylate crosslinking away from the surface.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate (EHEMA5, Mn=360), tetraethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TTEGDMA), azobisisobutryonitrile (AIBN), mercaptoethanol, dibutyltin dilaurate, hexamethylene diisocyanate (HMDI), triphenylphosphine (TPP), dimethoxyphenylacetophenone (DMPA) and fluorescein acrylate were received from Sigma-Aldrich. Methacryloxyethyl thiocarbamoyl rhodamine B (PolyFluor 570) was received from Polysciences. Allyl isocyanate (AI) was received from TCI America. Methyl ethyl ketone (MEK), methanol, ethanol and methanesulfonic acid (MsOH) were received from Fisher. Dexamethasone and divinyl sulfone (DVS) were received from VWR. Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP) and ethoxylated trimethylolpropane tri(3-mercaptopropionate) (ETTMP, Mn=1300) were donated by Evans Chemetics. AIBN was recrystallized from methanol. All other materials were used as received.

Cell culture

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were isolated from human bone marrow purchased from Lonza Bioscience™ following a previously described protocol41. The isolated hMSCs were cultured in growth media, which is low glucose DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 U/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin and 0.5 μg/ml fungizone. Recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-basic (FGF-2, Peprotech; 1 ng/ml) was added in the growth media during cell expansion on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) to maintain hMSCs stemness and promote proliferation. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passaged with trypsin digestion. hMSCs of passage 2 (P2) were used in this study.

Nanogel Synthesis

Nanogels were synthesized as previously described (see supporting information and42). Polyfluor 570 was included at 0.1 wt% to yield fluorescently tagged nanogels. Allyl isocyanate was used at 15 mol% to introduce allyl functionality after nanogel formation. Dexamethasone-loaded nanogels were created by swelling a 75 wt% nanogel dispersion in a 10 mg/mL solution of dexamethasone in methanol for 24 h and then removing the solvent under reduced pressure.

Nanogel Characterization

Nanogel molecular weight and hydrodynamic radius were determined using triple-detection gel permeation chromatography equipped with refractive index detection, right angle light scattering, and differential viscometer (Viscotek) with THF as the mobile phase (Fig S1 and S2). Mn = 16.0 kDa, Rh = 4.14 nm, PDI = 1.91, MH-α=0.271.

Shape Memory Polymer Synthesis

Step-growth thiourethane networks were created by adapting a previously described method40. Nucleophile-catalyzed thiol-isocyanate reactions can occur rapidly with gelation in less than 30 s, so a TPP/MsOH initiator/inhibitor system was prepared to allow for sufficient working time. Stock solutions of PETMP or ETTMP with TPP and MsOH were prepared such that the weight fraction of TPP and MsOH in the final formulations was 1.0 wt% and 0.2 wt%, respectively. HMDI was combined with the PETMP and ETTMP stock solutions to produce monomer stocks with thiol content and PETMP/ETTMP ratios as indicated in the following section. DVS was added at 4 wt% as a coinitiator. In some formulations, 0.01 wt% fluorescein acrylate was added. The monomeric resins were transferred to silicon rubber molds between glass slides and allowed to react until gelation was observed in a witness solution. The material was then post-cured at 80 °C for 30 min to overcome the limiting effect of network vitrification on final conversion.

Infrared Spectroscopy of SMP

FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet 6700, ThermoFisher) was used to verify residual thiol functionality with complete isocyanate conversion. A small sample of the previously described formulation was loaded between NaCl crystals, and an initial spectrum was obtained. The conversion of the –SH peak was monitored between 2500–2650 cm−1 and the -N=C=O peak was monitored at 2270 cm−1. The limiting conversion at room temperature was reached after 45 min, after which the sample was stored at 80 °C for 30 min and allowed to return to room temperature before a final spectrum was collected.

Coating Formation

A section of the SMP was immersed in a 55 °C water bath for 10 minutes to equilibrate the material above its glass transition temperature. The SMP was immediately dipped in a solution of 25 wt% nanogel in ethanol with 1.0 wt% DMPA, removed from the solution, and exposed to 365 nm UV light at 10 mW/cm2 for 20 to 60 s using a mercury arc lamp (Acticure, Exfo) with a bifurcated quartz light guide (Exfo) to provide uniform irradiation to both surfaces. Dexamethasone-loaded nanogels were used to form the coating with this same method where indicated.

NMR Analysis

1H NMR (Bruker, 400 MHz) was conducted on nanogels to determine the extent of intermolecular double bond conversion following UV irradiation. Spectra of a 10 wt% solution of nanogels in CDCl3 with 1.0 wt% DMPA were obtained, and the NMR tube was exposed to the same irradiation conditions as described in the coating formation. This procedure was repeated for nanogel solutions that also contained 10 wt% mercaptoethanol. Post-reaction spectra of the same samples were obtained immediately following irradiation.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

Rectangular sections of uncoated or coated SMP with dimensions of 15×2×1 mm were prepared as described above, soaked in acetone overnight, and dried under reduced pressure prior to analysis to ensure the complete removal of unreacted nanogels. Dynamic mechanical analysis was performed using a TA Q800 DMA. The glass transition temperature (Tg) and rubbery modulus (E) were determined using a temperature ramp of 3 °C/min with a 0.025% strain applied at 1 Hz. This cycle was repeated twice for each sample (n=3). The Tg and full width at half maximum (FWHM) were determined from the peak of the tan delta curve and E was determined from the rubbery plateau where the modulus effectively becomes invariant with temperature. Free strain recovery (Rr), shape fixity (Rf), and shape recovery sharpness (νr) were determined using the same rectangular samples. Samples were heated to 10 °C above their Tg, deformed to an initial strain (denoted ɛi), and cooled to −10 °C at −20 °C/min while maintaining the strain. The force was then set to zero and the strain upon unloading was recorded (denoted ɛu). The samples were then heated at rate of 3 °C/min to Tg + 10° C and the final strain was recorded (denoted ɛf). This cycle was repeated three times for each sample (n=3). The free strain recovery Rr, shape fixity Rf, and shape recovery sharpness νr were calculated as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ΔT is the width of the strain recovery transition. The toughness of the coated and uncoated SMPs in the dry and wet state was determined by straining the material to failure with a tensile tester (TestWorks) at 2 mm/min and calculating the area under the resulting stress-strain curve.

Confocal Microscopy

Coatings were imaged using a confocal microscope (A1R, Nikon) at 10× magnification and excited at 488 nm (GFP) and 561 nm (mCherry) where appropriate. Z-stacks were collected with a 10 μm step size over 200 μm.

In Vitro Release Study

Nanogels were dispersed in a 10 mg/mL solution of dexamethasone in methanol at 75 wt%. After 24 h the methanol was removed under reduced pressure to afford dexamethasone-loaded nanogels. Coatings were prepared using the dexamethasone-loaded nanogels as described above. Coated SMPs were placed in a 6-well low-binding polystyrene plate and covered with 2 mL of PBS. Three wells contained SMPs and three wells contained PBS only to minimize evaporative effects. Three non-overlapping sections of SMPs with approximate dimensions of 18×10×0.5 mm were placed in each well to produce a reliably detectable quantity of dexamethasone. The plate was wrapped in parafilm and stored at 37 °C with gentle agitation. The PBS was removed from each well every 24 h and replaced with 2 mL of fresh PBS. The samples were lyophilized and reconstituted in 70:30 water:acetonitrile for HPLC testing (Waters, 325 μL injection volume, 1 mL/min). The cumulative mass release per unit surface area of the shape memory polymer samples was determined from an absorbance-concentration calibration curve. To determine the release efficiency from these nanogels, dexamethasone-loaded nanogels were dispersed in PBS at 10 wt%, loaded into Float-A-Lyzer dialysis tubes (SpectraPor, 3.5–5 kDa MWCO), and stored in PBS in 50 mL Falcon tubes at 37 °C. The UV absorbance of dexamethasone at 260 nm was monitored every 24 h using a UV-Vis spectrometer (ThermoScientific), and the release efficiency was determined from the ratio of the initial dexamethasone absorbance to the absorbance after 10 days of release.

Transwell Release Study

P2 hMSCs were expanded on 150 mm TCPS until 80% confluency prior to trypsinization. Cells were pooled and seeded onto 24-well plate at 20,000 cells/cm2 with 1 mL of growth media. Cell attachment was allowed overnight, and the release study was started the following day. Materials coated with dexamethasone-loaded nanogel were washed with 10 mL of PBS three times to remove residual organic solvent before placing them into a 24-well transwell insert (BD Falcon, 1 μm pore size PET track-etched membrane) and filled with 1 mL of growth media. Each transwell insert with the material was placed on top of plated hMSCs cultured in 24-well plates. Additional control conditions were included with the plated cells cultured in growth media with 100nM soluble dexamethasone or co-cultured with materials without the dexamethasone coating. The plated hMSCs in each condition were harvested for alkaline phosphatase activity at Day 5.

Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Assay

Alkaline phosphatase activity of hMSCs was measured as previously described41. Specifically, hMSCs in each condition were washed with 1 ml of PBS and lysed by RIPA lysis buffer. Cell lysates were collected and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was reacted with the substrate of alkaline phosphatase (p-nitrophenyl phosphate) at 1:1 ratio. Mean velocity of the kinetic change of the absorbance at 405 nm of the reaction mixture was measured, and calculated as the relative ALP activity level. Dilution of the cell lysate was performed as needed to ensure that the enzyme activity was within the linear range.

Results and Discussion

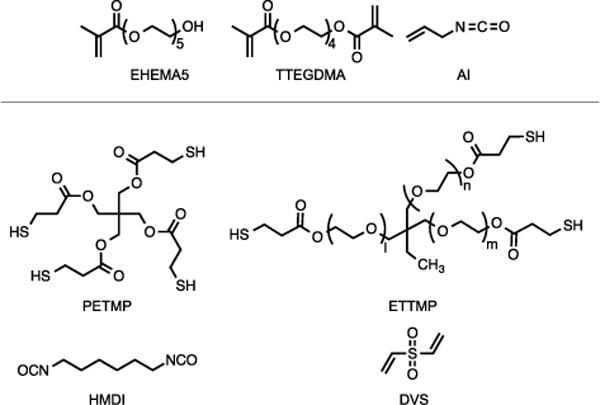

The goal of this study was to formulate a shape memory polymer with rapid thermal actuation at physiological temperatures with material chemistry that permits the formation of a drug-loaded nanogel-based coating without impairing shape recovery. The click reaction between multifunctional thiol and isocyanate monomers (Figure 2) allows for manipulation of functional group stoichiometry to provide thiol groups as a functional handle for post-polymerization modification. Furthermore, the step-growth reaction character produces homogeneous networks with narrow Tg compared to more heterogeneous chain-growth polymerizations36.

Figure 2.

Monomers used in the synthesis of nanogels (top) and SMP (bottom). For ETTMP, l ≈ m ≈ n ≈ 7.

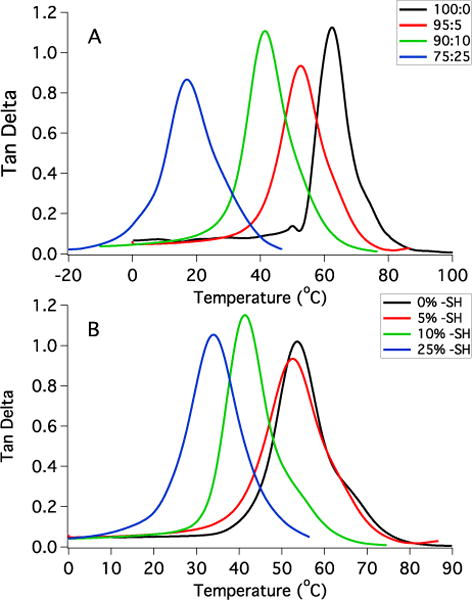

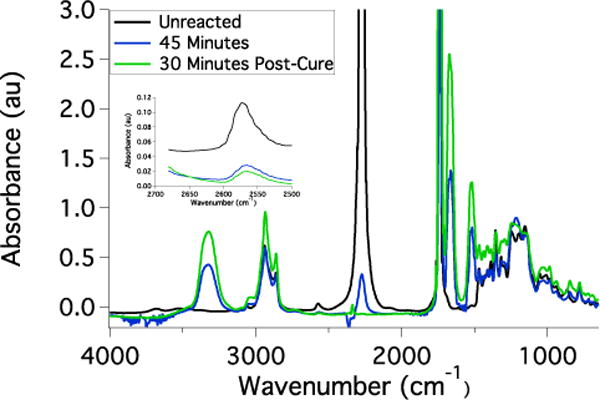

A monomer formulation was developed such that the Tg of the resulting network ensured activation at body temperature while allowing a stable temporary configuration at room temperature. HMDI and PETMP form highly crosslinked, glassy networks, and including ETTMP results in a more flexible, rubbery material. Varying the ratio of PETMP:ETTMP is a straightforward means of modifying the network crosslinking density and Tg as shown in Figure 3A. Networks containing a small excess of thiol groups and progressively increasing amounts of ETTMP exhibit a systematic decrease in Tg. PETMP-HMDI with no ETTMP remains in the glassy state below approximately 60 °C, which is unfavorable for body temperature actuation. The onset of glass transition shifts to lower temperatures with increasing amounts of ETTMP. It was found that 95:5 PETMP:ETTMP provided sufficient chain mobility to reduce the Tg and form networks with a shape recovery onset near 37 °C while maintaining a temporary shape at ambient temperature. Increasing the fraction of ETTMP to 90:10 and 75:25 PETMP:ETTMP resulted in networks that rapidly recovered their permanent shapes at ambient temperature. A continuous decrease in Tg was observed when the ratio of PETMP:ETTMP was held constant at 95:5 and the excess thiol content was increased from 0 to 25 mol% due to an overall increase in elastically inactive chain ends (Figure 3B). However, the decrease in Tg observed between 0 and 5 mol% excess thiol was small, and it was hypothesized that networks containing this thiol quantity would be sufficient to permit secondary reactions with nanogels without incurring a dramatic decrease in network mechanics. Based on these observations, a shape memory polymer formulation of PETMP-ETTMP-HMDI with 95:5 PETMP:ETTMP and 5% excess thiol was selected for further use in this study. This monomer formulation reached a high conversion of thiol and isocyanate groups at room temperature, but vitrification prevented complete conversion of isocyanates until heat was applied as shown in Figure 4. Within 30 min of thermal post-curing the isocyanate peak could not be distinguished from the baseline and the thiol conversion reached 90%. Since thiol groups were included at 5% molar excess, this discrepancy is likely attributed to monomer purity and the presence of small amounts of ambient moisture that can change the actual reaction stoichiometry compared to the predicted values.

Figure 3.

Glass transition behavior of PETMP-ETTMP-HMDI networks with varying composition. A: Increasing the molar ratio of PETMP:ETTMP with 5% total excess thiol groups. B: Increasing the quantity of excess thiol groups for PETMP-ETTMP-HMDI networks formulated with 95:5 PETMP:ETTMP.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of the HMDI-PETMP-ETTMP networks bearing excess thiol functionality. The reductions in isocyanate (2270 cm−1) and thiol peaks (2500–2600 cm−1) accompanied by the appearance of urethane amine (3400 cm−1) and carbonyl peaks (1600 cm−1) are indicative of thiourethane network formation. The isocyanate peak was saturated in this spectrum and was not used for quantitative analysis.

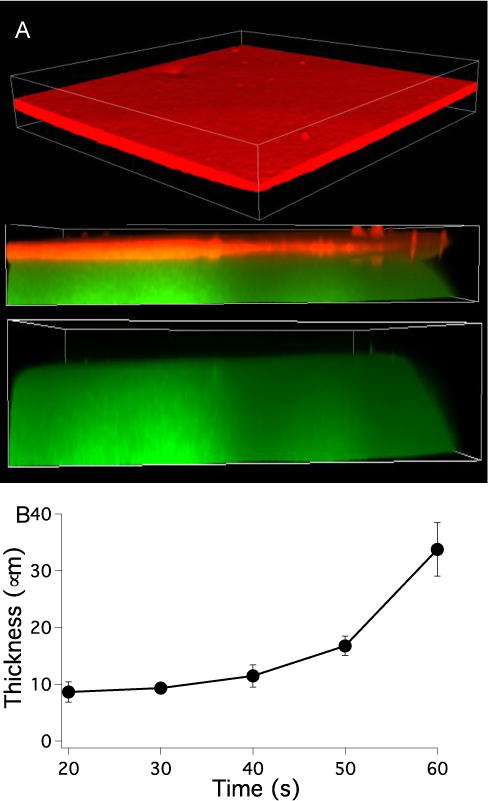

We have previously demonstrated that nanogels can be efficiently functionalized with methacrylate groups via an alcohol-isocyanate click reaction and directly polymerized into crosslinked networks in the absence of small monomer42,43. Previous reports have further detailed the formation of covalently conjugated nanogel-based coatings on functionalized surfaces using a variety of click reactions including alkyne-azide, thiol-alkyne, and Michael addition reactions44,45. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that allyl isocyanate can be used analogously to synthesize nanogels that participate in radical-mediated thiol-ene reactions with little to no homopolymerization, which we predicted will lead to uniform coatings on SMPs containing surface thiol groups. Confocal microscopy confirmed that spatially homogeneous coatings resulted from the dip-coating and subsequent photocrosslinking procedures (Figure 5A). The SMP substrate was labeled with fluorescein to more clearly distinguish between the coating and the SMP surface and to confirm that the nanogel remained on the surface and had not diffused extensively into the SMP. Water contact angle testing of the uncoated (59 ± 0.6°) and nanogel-coated (24 ± 2°) SMPs further confirmed the presence of the coating on the polymer surface and also demonstrated the ability of this nanogel formulation to render the surface hydrophilic. The thickness of the coating was approximately 30 μm, which is much greater than the average nanogel radius, and extensive washing confirmed that the coating was not the result of physical adsorption. It was not expected that the allyl groups would permit crosslinking between nanogels, so this observation appears to indicate the presence of residual pendant unreacted methacrylate groups in the nanogel. Previous studies have demonstrated that nanogels bearing pendant methacrylates exhibit significant reactivity34, which in this system can lead to homopolymerization or copolymerization with the allyl groups to form an extended network structure. Peaks corresponding to both methacrylate and allyl protons on the nanogels were present and distinguishable using 1H NMR analysis (Figure S3). When a solution of nanogels containing photoinitiator is exposed to UV light, the ratio of allyl protons to methacrylate protons after photoirradiation increases by a factor of 3 from 4.1:1 to 12.7:1. This indicates preferential methacrylate group consumption compared to allyl consumption and supports the hypothesis that methacrylate homopolymerization is a factor in producing the coatings. When a solution of nanogels was exposed to UV light with photoinitiator and mercaptoethanol as a model thiol compound, the complete disappearance of all vinyl protons was observed (Figure S4). These results together demonstrate that both allyl and methacrylate groups can react with surface thiols while only methacrylate groups react away from the surface in the absence of thiol groups. Coating thickness increased when the dip-coated SMPs were irradiated for longer times (Figure 5B), which is additional evidence for the methacrylate contribution and indicates that the duration of UV exposure is an effective method for controlling coating formation. Additional attempts to form photoinitiated coatings on networks prepared with excess isocyanate groups instead of excess thiol groups were unsuccessful, as determined by confocal microscopy and contact angle testing, as were attempts to form coatings by dip coating without irradiation (water contact angle 58 ± 0.7°). These results together indicate that both surface and bulk covalent bonds are contributing to the formation of the coating. While this mechanism is different from the one initially hypothesized, these results outline a mild, facile method for creating conformal coatings that only require a small off-stoichiometric ratio to be implemented in the base SMP chemistry. Furthermore, a single layer of nanogel may release a drug too rapidly or contain a physiologically ineffective quantity of drug. Producing coatings of thickness on the micron scale is potentially advantageous for prolonging release rate and controlling total quantity of drug delivered. Future work could involve alternative preparation methods such as spin coating or spray coating46 nanogels prior to surface crosslinking to exercise further control over coating thickness and morphology.

Figure 5.

A: Confocal microscope imaging of rhodamine-labeled nanogels coated onto fluorescein-labeled HMDI-PETMP-ETTMP SMPs bearing excess thiol functionality. A side view of the same material is shown with the mCherry channel added or subtracted to indicate the location of the interface between the coating and SMP. Vertical dimension is 200 μm and coating thickness is approximately 30 μm. B: Coating thickness as a function of irradiation time. Each sample was exposed to 365 nm light at 10 mW/cm2. No coating was observed with 10 s irradiation.

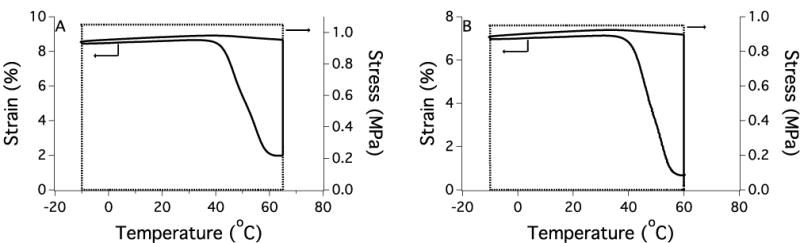

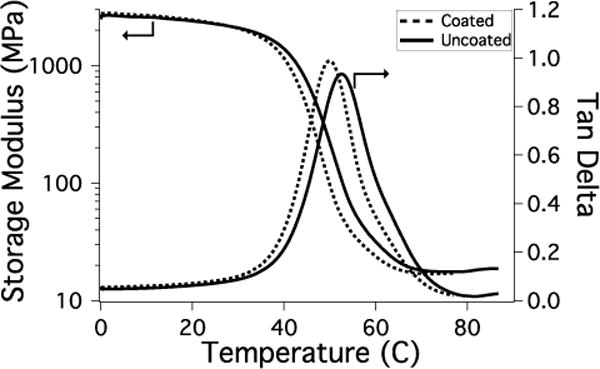

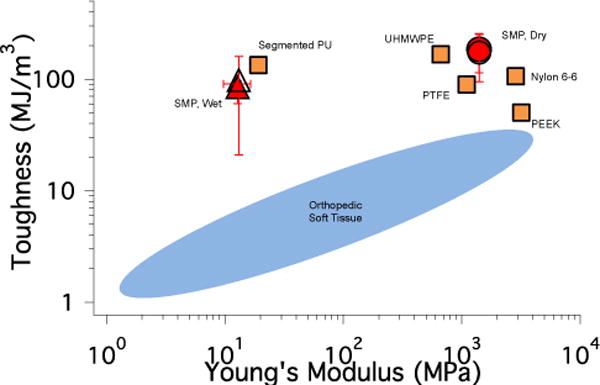

Since the coating on the SMPs in these studies is approximately 10–30 μm, it is critical to verify that the properties of the SMP base material are unaffected and the shape memory behavior is preserved. Dynamic mechanical testing was used to demonstrate that the nanogel coating did not disrupt the shape memory behavior of the thiourethane network. Both the uncoated and coated materials maintain well above 90% free strain recovery and shape fixity with no significant decrease observed for the coated material (Figure 6 and Table 1). Free strain recovery indicates the extent to which the polymer recovers its permanent shape, and shape fixity is a measure of the ability to maintain a temporary shape below the glass transition temperature. The results for these two metrics are comparable to previously reported thiol-ene step-growth shape memory polymers37 and polyurethane SMPs47, and verify that these thiourethane networks perform well as shape memory materials when a coating is applied. The shape recovery sharpness is a measure of how rapidly the material transitions to its permanent shape upon heating and was unchanged with the addition of the coating. Furthermore, the onset of strain recovery for both materials was close to physiological temperature and no appreciable strain recovery was observed at ambient temperature. If strain recovery began at or near room temperature, the materials may lose their temporary shape prior to exposure to body temperature, so this system could provide increased stability and workability in this temperature range. The thermomechanical properties of the SMP (Figure 7) show a small decrease in bulk glass transition temperature and rubbery modulus for the coated material since a low Tg network is essentially formed at the SMP surface. However, the thermal transition is sharp for both the uncoated and coated materials, and no shouldering or broadening of the tan delta curve indicates that the coated material continues to behave like a homogeneous step-growth network and not a multiphase network. The toughness of the coated and uncoated SMPs in both the dry and water-equilibrated state was calculated from the stress-strain curve of the polymers under tension. The coating had no effect on the toughness and Young’s modulus of the SMP (Figures 8 and S5). The water-equilibrated samples were significantly plasticized as evidenced by the lower Young’s modulus, but the toughness remained comparable to the dry state. Furthermore, the SMP mass in the swollen state was constant over 10 days (Figure S6), which indicates that the decrease in Young’s modulus was not due to network degradation. Figure 8 plots the toughness vs. Young’s modulus for the SMPs along with values that are representative of several commercially available polymers that have been used as medical implants8. The thiourethane SMPs match well with materials that possess both high toughness and high modulus. These values are slightly above the high end of the range that matches the properties of native orthopedic soft tissue, which indicates that the nanogel-coated thiourethane SMP exhibits mechanical properties that are relevant to implantable medical devices that currently have clinical application, and could be further tuned to more closely resemble the stiffness of its biological environment.

Figure 6.

Shape recovery of uncoated (A) and coated (B) polymers (95:5 PETMP:ETTMP, 5% excess –SH) from a representative stress (−) and strain (---) loading/unloading cycle.

Table 1.

Dynamic mechanical analysis results of the thermomechanical properties and shape recovery for uncoated and nanogel-coated polymer substrates (95:5 PETMP:ETTMP, 5% excess –SH).

| Tg (C) | Full Width at Half Maximum (C) | E’ (MPa) | Free Strain Recovery (%) | Shape Fixity (%) | Shape Recovery Sharpness (%/ °C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncoated | 51 ± 1 | 14 ± 3 | 19 ± 1 | 97 ± 3 | 98 ± 2 | 3.8 ± 0.3 |

| Coated | 47 ± 2 | 13 ± 1 | 17 ± 2 | 92 ± 5 | 96 ± 2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

Coatings approximately 30 μm thick were formed using EHEMA5-TTEGDMA nanogels.

Figure 7.

Rubbery modulus and glass transition of coated (--) and uncoated (−) polymers (95:5 PETMP:HMDI, 5% excess –SH).

Figure 8.

Toughness vs. Young’s modulus of the coated (open symbol) and uncoated (filled symbol) SMP (95:5 PETMP:ETTMP, 5% excess –SH) in the dry (●) and water-equilibrated (wet) state (▲) plotted with typical values for commercially available polymers used for shape memory. The range of values for orthopedic soft tissue is shown for reference. The data and general layout of this plot was adapted from reference 8. PU: poly(urethane), UHMWPE: ultra-high molecular weight poly(ethylene), PTFE: poly(tetrafluoroethylene), PEEK: poly(ethyl ether ketone) (■).

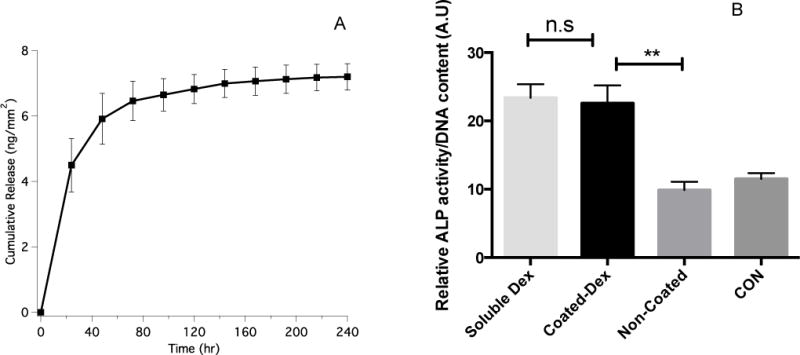

Coatings were formed with nanogels that were loaded with dexamethasone to evaluate the release rate of a drug from the coated SMP (Figure 9A). An initial burst release was observed after 24 h followed by gradual release over the following 9 days. Current reports on SMPs that exhibit burst release kinetics over ~1 week also have significant mass loss and degradation of mechanical properties during this time, while the materials reported here show no mass loss over this interval (Figure S6). This observation highlights the ability of these coated materials to release a drug without any chemical or physical change to the base SMP polymer. To test whether the shape memory polymer can release physiologically relevant quantities of a small molecule drug, dexamethasone loaded nanogels were coated on the surface of the SMP and introduced to hMSCs to induce osteogenesis (Figure 9B). Dexamethasone is a potent small molecule (MW 392) that can promote hMSCs alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP), an early marker of osteogenesis at 10 nM to 100 nM concentrations. In control conditions, the addition of 100 nM soluble dexamethasone in the media (denoted as Soluble Dex) induced a 2-fold ALP activity of hMSCs compared to the blank control (CON) at Day 5. In test conditions, the nanogel-coated shape memory polymer released dexamethasone at a nanomolar concentration that promoted hMSCs ALP activity to a similar level as soluble dexamethasone, which is significantly higher than that of non-coated material (α=0.05). These results verified that dexamethasone remained bioactive during the coating procedure and that the coated SMPs containing dexamethasone can release a sufficient amount of drug to elicit a cellular response in physiological conditions.

Figure 9.

A: Cumulative dexamethasone release over 10 days from coated SMPs. B: Alkaline phosphatase activity of hMSCs after 5 days of culturing with soluble dexamethasone (Soluble Dex) or co-culturing with SMPs coated with dexamethasone-loaded nanogels (Coated-Dex) or uncoated SMPs (Non-Coated). The negative control condition (CON) was growth media.

Conclusions

Thiourethane shape memory polymer networks were synthesized from the step-growth copolymerization of multifunctional thiol and isocyanate monomers. Networks containing excess thiol groups were coated with nanogels bearing both allyl and methacrylate groups through a dip-coating and subsequent photoinitiated crosslinking method. Uniform coatings formed within 60 s at ambient conditions, and coating thickness increased as a function of UV light exposure. The mechanical properties and thermally-induced shape recovery behavior of the polymers were unaffected by the presence of the coating, and a high degree of free strain recovery and shape fixity along with rapid shape recovery were observed. Dexamethasone-loaded nanogels were coated onto the SMPs, which exhibited a burst release of the drug followed by gradual release over the timescale of days. Dexamethasone remained bioactive and the amount released was sufficient to induce osteogeneic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. We predict that this system will be optimal where localized release of high potency small molecule drugs that are active at small (i.e. nM) quantities is desired, rather than for systemic release that may require higher (i.e. mM) dosages, or for the delivery of larger biomolecular therapeutics. This system effectively separated the drug delivery and shape memory functions and can serve as a platform for designing multifunctional materials in which drug release functionality can be incorporated without affecting the primary function of the material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Matthew Barros for GPC characterization and the University of Colorado Biofrontiers Advanced Imaging Resource. The study was funded by NIH/NIDCR through R01DE023197.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: 1H NMR spectra, stress-strain measurements of SMPs, and bulk water swelling measurements. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Serrano MC, Ameer GA. Macromol Biosci. 2012;12(9):1156–1171. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201200097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behl M, Razzaq MY, Lendlein A. Adv Mater. 2010;22(31):3388–3410. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lendlein A, Behl M, Hiebl B, Wischke C. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2010;7(3):357–379. doi: 10.1586/erd.10.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kratz K, Voigt U, Lendlein A. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22(14):3057–3065. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Q, Behl M, Lendlein A. Soft Matter. 2013;9(6):1744. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Li Y, Liu Y, Gong T, Wang L, Zhou S. Polym Chem. 2014;5(17):5168. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Huang W, Zhao Y, Ding Z, Tang C, Zhang J. Polymers. 2013;5(4):1169–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safranski DL, Smith KE, Gall K. Polym Rev. 2013;53(1):76–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wischke C, Behl M, Lendlein A. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10(9):1193–1205. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.797406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musiał-Kulik M, Kasperczyk J, Smola A, Dobrzyński P. Int J Pharm. 2014;465(1–2):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi N, Lendlein A. Soft Matter. 2007;3(7):901. doi: 10.1039/b702515g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng Y, Zhang S, Wang H, Zhao H, Lu J, Guo J, Behl M, Lendlein A. J Control Release. 2011;152(Suppl):e21–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.098. (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng Y, Behl M, Kelch S, Lendlein A. Macromol Biosci. 2009;9(1):45–54. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagahama K, Ueda Y, Ouchi T, Ohya Y. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(7):1789–1794. doi: 10.1021/bm9002078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neffe AT, Hanh BD, Steuer S, Lendlein A. Adv Mater. 2009;21(32–33):3394–3398. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano MC, Carbajal L, Ameer Ga. Adv Mater. 2011;23(19):2211–2215. doi: 10.1002/adma.201004566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wischke C, Neffe AT, Steuer S, Lendlein A. J Control Release. 2009;138(3):243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wischke C, Neffe AT, Steuer S, Engelhardt E, Lendlein A. Macromol Biosci. 2010;10(9):1063–1072. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao Y, Zhou S, Wang L, Zheng X, Gong T. Compos Part B Eng. 2010;41(7):537–542. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Feng Y, Zhang L, Guo J, Xu Y. J Appl Polym Sci. 2009;116:861–867. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao M, Zhou Q, Dong W, Lou X, Zhang Y. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1971–1979. doi: 10.1021/bm4003464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li G, Fei G, Xia H, Han J, Zhao Y. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(16):7692. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han J, Fei G, Li G, Xia H. Macromol Chem Phys. 2013;214:1195–1203. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Cao Y, You Q, Zhang Y, Shi H, Yang Z, He L, Wang J, Ni C, Chen Y, Qian Z. Mater Express. 2013;3(4):310–318. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wischke C, Neffe AT, Steuer S, Lendlein A. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;41(1):136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercanzini A, Reddy ST, Velluto D, Colin P, Maillard A, Bensadoun J-C, Hubbell Ja, Renaud P. J Control Release. 2010;145(3):196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shukla A, Avadhany SN, Fang JC, Hammond PT. Small. 2010;6(21):2392–2404. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siepmann F, Siepmann J, Walther M, MacRae RJ, Bodmeier R. J Control Release. 2008;125(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An Z, Qiu Q, Liu G. Chem Commun. 2011;47(46):12424. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13955j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh JK, Drumright R, Siegwart DJ, Matyjaszewski K. Prog Polym Sci. 2008;33(4):448–477. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raemdonck K, Demeester J, de Smedt S. Soft Matter. 2009;5(4):707–715. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bencherif SA, Siegwart DJ, Srinivasan A, Horkay F, Hollinger JO, Washburn NR, Matyjaszewski K. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5270–5278. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dailing E, Liu J, Lewis S, Stansbury J. Macromol Symp. 2013;329(1):113–117. doi: 10.1002/masy.201200109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Howard GD, Lewis SH, Barros MD, Stansbury JW. Eur Polym J. 2012;48(11):1819–1828. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iha RK, Wooley KL, Nyström AM, Burke DJ, Kade MJ, Hawker CJ. Chem Rev. 2009;109(11):5620–5686. doi: 10.1021/cr900138t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair DP, Podgorski M, Chatani S, Gong T, Xi W, Fenoli CR, Bowman CN. Chem Mater. 2014;26:724–744. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nair DP, Cramer NB, Scott TF, Bowman CN, Shandas R. Polymer. 2010;51(19):4383–4389. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsushima H, Shin J, Bowman CN, Hoyle CE. J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem. 2010;48(15):3255–3264. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hensarling RM, Rahane SB, LeBlanc AP, Sparks BJ, White EM, Locklin J, Patton DL. Polym Chem. 2011;2(1):88. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chatani S, Sheridan RJ, Podgorski M, Bowman CN. Chem Mater. 2013;25:3897–3901. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariner PD, Johannesen E, Anseth KS. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6:314–324. doi: 10.1002/term.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dailing EA, Lewis SH, Barros MD, Stansbury JW. J Dent Res. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0022034514552490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dailing Ea, Setterberg WK, Shah PK, Stansbury JW. Soft Matter. 2015;11:5647–5655. doi: 10.1039/c4sm02788d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tessler La, Donahoe CD, Garcia DJ, Jun Y-S, Elbert DL, Mitra RD. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8(63):1400–1408. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donahoe CD, Cohen TL, Li W, Nguyen PK, Fortner JD, Mitra RD, Elbert DL. Langmuir. 2013;29:4128–4139. doi: 10.1021/la3051115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saez-Martinez V, Olalde B, Jesus Juan M, Jesus Jurado M, Garagorria N, Obieta I. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2010;10:2826–2832. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baer G, Wilson TS, Matthews DL, Maitland DJ. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;103:3882–3892. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.