The first crystal structure of the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM complex has been determined at 2.2 Å resolution. Comparison to other UHM–ULM complexes reveals both common and unique interactions.

Keywords: RNA-binding proteins, alternative splicing, U2AF homology motif, CAPERα, HCC1, RBM39, RNA-binding protein 39, U2AF5, UHM, ULM

Abstract

RNA-binding protein 39 (RBM39) is a splicing factor and a transcriptional co-activator of estrogen receptors and Jun/AP-1, and its function has been associated with malignant progression in a number of cancers. The C-terminal RRM domain of RBM39 belongs to the U2AF homology motif family (UHM), which mediate protein–protein interactions through a short tryptophan-containing peptide known as the UHM-ligand motif (ULM). Here, crystal and solution NMR structures of the RBM39-UHM domain, and the crystal structure of its complex with U2AF65-ULM, are reported. The RBM39–U2AF65 interaction was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation from human cell extracts, by isothermal titration calorimetry and by NMR chemical shift perturbation experiments with the purified proteins. When compared with related complexes, such as U2AF35–U2AF65 and RBM39–SF3b155, the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM complex reveals both common and discriminating recognition elements in the UHM–ULM binding interface, providing a rationale for the known specificity of UHM–ULM interactions. This study therefore establishes a structural basis for specific UHM–ULM interactions by splicing factors such as U2AF35, U2AF65, RBM39 and SF3b155, and a platform for continued studies of intermolecular interactions governing disease-related alternative splicing in eukaryotic cells.

1. Introduction

Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA is a prevalent mechanism for increasing the genomic coding capacity by the coordinated removal of introns and differential exon joining to produce different coding mRNAs from the same primary transcript (Black, 2003 ▸). Functional alterations of proteins involved in regulating alternative splicing are implicated in immune diseases and cancer development, demonstrating the functional importance of controlled alternative splicing (Lynch, 2004 ▸; Moore et al., 2010 ▸; Venables, 2006 ▸; Srebrow & Kornblihtt, 2006 ▸). In higher eukaryotes, spliceosome assembly begins with recognition of the 5′ splice site by U1snRNP and binding of U2 auxiliary factor (U2AF) to the polypyrimidine tract (Py-tract) and the 3′ splice site. U2AF is required for the stable association of the U2 snRNP with the pre-mRNA branch-point sequence during the first ATP-dependent step of the splicing process (Complex A). The U2AF protein complex consists of large (U2AF65) and small (U2AF35) subunits that form a stable heterodimer that binds to the AG dinucleotide at the 3′ splice site (Merendino et al., 1999 ▸; Zorio & Blumenthal, 1999 ▸; Wu et al., 1999 ▸). U2AF65 is essential for splicing, and binding of U2AF65 alone is sufficient for bending the Py-tract, juxtaposing the branch region and the 3′ splice site (Kent et al., 2003 ▸). U2AF35 is dispensable for in vitro pre-mRNAs containing strong Py-tracts (Burge et al., 1999 ▸), but is required for in vitro splicing of a pre-mRNA substrate with a Py-tract that deviates from the consensus (Guth et al., 1999 ▸).

U2AF65 contains an N-terminal arginine/serine-rich (RS) domain followed by two RNA-recognition motifs (RRM) and a third C-terminal noncanonical RRM (Fig. 1 ▸ a; Mollet et al., 2006 ▸; Kielkopf et al., 2004 ▸) that mediates protein–protein domain interactions and is commonly termed the U2AF homology motif (UHM). Besides the association between protein and RNA, specific protein–protein interactions are often needed to recruit and coordinate the assembly of splicing factors at the sites of mRNA processing. UHMs are found in several other nuclear proteins, such as PUF60, SPF45, U2AF35 and RBM39 (Fig. 1 ▸ a), which are linked to constitutive and alternative splicing through UHM-mediated protein–protein interactions to short tryptophan-containing linear UHM ligand motifs (ULMs). A consensus ULM sequence [(K/R)4–6 X 0–1W(D/E/N/Q)1–2] is found in several nuclear proteins, including U2AF65, SF1 and SF3b155 (Page-McCaw et al., 1999 ▸; Corsini et al., 2007 ▸, 2009 ▸; Manceau et al., 2006 ▸; Fig. 1 ▸ b). Moreover, the UHM–ULM protein–protein interaction is involved in a number of higher order complexes, including the constitutive 3′ splice site U2AF35–U2A65 complex (Kielkopf et al., 2001 ▸), U2AF65 in complex with splicing factor SF1 binding to the Py-tract (Selenko et al., 2003 ▸) and alternative splicing factors SPF45 and RBM39 associated with the ULM of SF3b155 (Corsini et al., 2007 ▸; Loerch et al., 2014 ▸). In addition, it has been proposed that the U2AF65 subunit might form structurally similar heterodimers with a diverse set of UHM proteins with distinct functional activities in a tissue-specific manner.

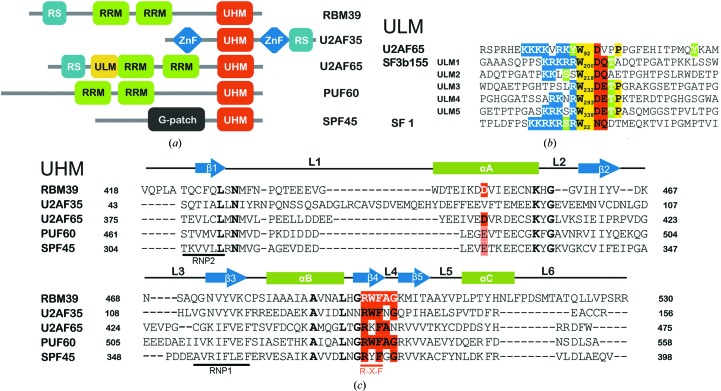

Figure 1.

UHM and ULM domains in splicing factors. (a) Domain composition and arrangement of nuclear proteins containing UHM domains. (b) Sequence alignment of nuclear splicing factors that contain ULM motifs [(K/R)4–6 X 0–1W(D/E/N/Q)1–2]. Conserved tryptophans are highlighted in yellow, conservative negatively charged and polar amino acids following the tryptophan are highlighted in red and the N-terminal stretch of positively charged amino acids is highlighted in blue. Potential in vivo phosphorylated sites are indicated in green. (c) Sequence alignment of the UHM domains shown in (a). The conserved amino acids known to be involved in the ‘knob-into-hole’ interaction are highlighted in red, and their homologous substitutions are in light red. RBM39 residues that directly bind to U2AF65-ULM are shown in white on a red background.

The UHMs are noncanonical RRMs that have nonconsensus residues in the RNP1 and RNP2 RNA-binding motifs and instead contain two ULM-recognition motifs: one motif consists of an arginine–any amino acid (X)–phenylalanine (R-X-F) element (Kielkopf et al., 2001 ▸, 2004 ▸; Selenko et al., 2003 ▸; Fig. 1 ▸ c) and the other an extended negatively charged α-helix A. The ULM consensus sequence therefore includes two different binding motifs. In the structure of U2AF65-UHM complexed with SF1-ULM, the positively charged N-terminal segment of the ULM winds along the negatively charged α-helix A of U2AF65, while the consensus tryptophan docks into a cavity formed by α-helices A and B. In the U2AF35-UHM–U2AF65-ULM structure the primary interface occurs between the R-X-F element of the UHM and the C-terminal region of the ULM sequence, and is driven by reciprocal tryptophan interactions, in which a Trp residue on one protein occupies a Trp pocket on the other protein.

RNA-binding protein 39 (RBM39), also known as CAPERα or HCC1, exhibits the same domain architecture as U2AF65 and contains both the R-X-F element and a negatively charged α-helix A characteristic of the UHM. RBM39 is both a splicing factor and a transcriptional co-activator of AP-1/Jun and estrogen receptors (Imai et al., 1993 ▸; Dowhan et al., 2005 ▸). RBM39 function has been linked to a number of cancers and malignant progression (Sillars-Hardebol, Carvalho, Tijssen et al., 2012 ▸), and the RBM39-interacting proteins in particular environments determine the anti- or pro-oncogenic activity of RBM39. RBM39 expression is up-regulated in small-cell lung and breast cancers, colorectal adenomas and carcinomas (Bangur et al., 2002 ▸; Mercier et al., 2009 ▸; Chai et al., 2014 ▸; Sillars-Hardebol, Carvalho, Beliën et al., 2012 ▸). Knockdown of RBM39 expression suppresses the oncogenic activity of the NF-κBv v-Rel protein in lymphocytes (Dutta et al., 2008 ▸) and the proliferation of ER-positive human breast cancer cells. Down-regulation of RBM39 activity decreases the expression of cell-cycle progression regulators, abrogates the protein-synthesis pathway and attenuates the phosphorylation of c-Jun (Mercier et al., 2014 ▸).

RBM39 further mediates alternative splicing, which results in the expression of two isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), VEGF165 and VEGF189, in breast cancer and Ewing sarcoma. However, in contrast to the tumor-suppression effects in other cancers, down-regulating RBM39 expression shifts the ratio of VEGF isoforms to the more angiogenic VEGF165 form in Ewing sarcoma cells, which correlates with increased tumor vascularity and malignancy in vivo (Huang et al., 2012 ▸). There are three human RBM39 isoforms, and at least two of them behave as tumor-associated antigens that can induce humoral immune responses in lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma patients (Chai et al., 2014 ▸). Recent reports have implicated RBM39 in controlling cell proliferation, and RMB39 in complex with TBX3 is required for preventing senescence in primary cells and mouse embryos (Kumar, Emechebe et al., 2014 ▸).

RBM39 is also a component associated with the human spliceosome that interacts in an RNA-independent manner with the U2AF heterodimer (Ellis et al., 2008 ▸), U2AF65 itself (Prigge et al., 2009 ▸), SF3b155 (Ellis et al., 2008 ▸; Prigge et al., 2009 ▸) and splicing factor RSRC1, which is also known to activate weak 3′ splice sites (Cazalla et al., 2005 ▸). The interaction of RBM39 with these components may provide the opportunity to regulate the splicing of specific transcripts by modulating the interactions leading to the definition of the 5′ splice site, branch point or 3′ splice site.

The specificity of RNA–protein interactions that regulate alternative splicing is often conferred by co-association of proteins within enhancer or silencer complexes (Lynch & Maniatis, 1996 ▸; Markovtsov et al., 2000 ▸). Alternatively, spliced exons are often preceded by a weak pyrimidine tract and their splicing is dependent on exonic splice-enhancer elements (Blencowe, 2000 ▸; Graveley, 2000 ▸). Decreased activity of a splicing factor involved in 3′ splice-site selection has the greatest effect on substrates that have weak or variable 3′ splice sites (Konarska & Query, 2005 ▸). The splicing regulator polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB1) represses the excision of an alternatively spliced exon by preventing the 5′ splice-site-dependent assembly of U2AF on the 3′ splice site (Sharma et al., 2005 ▸). However, RBM39 promotes the inclusion of a pseudoexon in the iron–sulfur cluster-assembly gene ISCU by interfering with PTB1 binding and repression (Nordin et al., 2012 ▸). Thus, it is also possible that variant complexes with U2AF provide a flexible regulation mechanism involving tissue-specific splicing choices determined by regulators such as PTB1 or RBM39.

In this regard, RBM39 mRNA expression displays a distinct tissue-specific pattern in healthy tissues and is abundant in immune system-associated cells, as well as lymph-node cells, uterus, thyroid and pineal gland cells. RBM39 mRNA is highly transcribed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, CD56+ natural killer cells, CD19+ B-lymphocytes, CD33+ myeloid and CD34+ cells (Su et al., 2004 ▸). Although the crucial role of RBM39 in cancer development and progression is supported by a number of reports, the RNA-binding specificity, the protein–protein interacting partners and its regulatory role in alternative splicing have yet to be determined.

Here, we use a combination of biochemical and biophysical methods, including NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography, to characterize the UHM–ULM interaction between RBM39 and U2AF65. In addition, the RBM39–U2AF65 complex structure is compared with two other available UHM–ULM complex structures, revealing a conserved core set of interactions, as well as interactions that are specific for certain complexes, which may be important for the UHM–ULM specificity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and transfection

The U2AF65 (NCBI BC043071) ULM (residues 79–142) and RS-ULM (residues 1–142) constructs were cloned by PCR amplification using cDNA generated from Jurkat T cells as a template. Restriction sites were incorporated into the forward (BamHI) and reverse (XhoI) primers. The PCR products were digested and ligated into a modified pcDNA3.1B V5-6His backbone, where GFP was inserted upstream of the V5-6His tag. 293T cells were seeded onto 10 cm dishes the night before transfection such that the cells were 40–60% confluent the next day. The cells were transfected with 30 µg plasmid DNA using the ProFection mammalian transfection system (Promega). The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

2.2. Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in cold FLAG lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 with 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1% Triton X-100) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche), sonicated and then clarified by centrifugation at 12 000g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by the BCA assay (Pierce). Immunoprecipitation was performed with 1.5 mg total protein and 15 µl FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma). Lysis buffer was added to bring the immunoprecipitation volume to 1 ml, followed by incubation overnight in a rotator at 4°C. The beads were then washed six times with lysis buffer. Where indicated, RNase A treatment was performed on the beads by resuspending the beads in 500 µl lysis buffer with RNase A after the first wash and then incubating for 15 min at 37°C. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by resuspending the beads in 2× NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies), followed by incubation at 70°C for 10 min.

2.3. Western blotting

Cell lysates and immunoprecipitation eluates were resolved on a bis-tris 4–12% NuPAGE precast gel and then transferred onto an Immobilon-FL PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with blocking buffer (LI-COR) and then probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Afterwards, the blot was washed three times with PBST (PBS + 0.05% Tween 20), probed with the appropriate secondary antibody, washed another three times and then scanned on an LI-COR Odyssey imaging system.

The following antibodies were used. The primary antibodies were monoclonal anti-V5 (Life Technologies), rabbit polyclonal anti-actin (Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-U2AF35 (Bethyl Laboratories) and rabbit polyclonal anti-RBM39 (Bethyl Laboratories), and the secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse (LI-COR) and goat anti-rabbit (LI-COR).

2.4. Protein-sample preparation

RBM39 (NCBI BC030493) clones were generated using the polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) cloning method (Klock et al., 2008 ▸). Mouse RBM39-UHM domain RRM3 (residues 418–530), RRM1 (144–234), RRM2 (248–326) and RRM1-RRM2 (144–326) gene truncations were cloned in pSpeedET expression vector with an N-terminal TEV protease-cleavable purification His tag (MGSDKIHHHHHHENLYFQ/G). The amino-acid sequences of the mouse RBM39 and U2AF65 domain constructions used in this study are identical to the human protein isoforms. RBM39 surface mutations Asn468Tyr and Thr510Tyr were introduced into the UHM domain to improve the crystallization of the RBM39–U2AF65 complex, and Trp495Ala and Asp449Trp mutations were designed to disrupt the interaction with the U2AF65-ULM peptide (Table 1 ▸). The U2AF65 (NCBI BC043071) ULM (residues 85–112, 88–112 and 79–142) truncations were expressed as N-terminal GST fusions in pGEX-4T-1 vector with a modified TEV protease-cleavage site.

Table 1. RBM39 and U2AF65 dissociation constants as measured by ITC.

Average values and SDs of three independent experiments are given. ΔG 0 was calculated using ΔG 0 = −RTln(K d); −TΔS 0 = ΔG 0 − ΔH 0, T = 298.15 K.

| U2AF65 | RBM39 | K d (10−6 M) | N † | ΔG 0 (kcal mol−1) | ΔH 0 (kcal mol−1) | −TΔS 0 (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULM (85–112) | RRM3 (UHM) (418–530), WT | 20.5 ± 2.8 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | −6.4 ± 0.1 | −6.9 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.8 |

| RRM3 (UHM) (418–530), Asn468Tyr | 14.8 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | −6.6 ± 0.1 | −6.7 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | |

| RRM3 (UHM) (418–530), Thr510Tyr | 20.8 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | −6.4 ± 0.1 | −7.3 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | |

| RRM3 (UHM) (418–530), Trp495Ala | ‡ | |||||

| RRM3 (UHM) (418–530), Asp449Trp | ‡ | |||||

| (P)-Tyr91 ULM (85–112) | WT | 31.9§ | 1.4 | −6.1 | −3.1 | −3.0 |

| (P)-Tyr107 ULM (88–112) | WT | 29.1 ± 3.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | −6.2 ± 0.07 | −5.8 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.9 |

| ULM (85–112) | RRM1 (144–234) | ‡ | ||||

| RRM2 (248–326) | ‡ | |||||

| RRM1-RRM2 (144–326) | ‡ |

Apparent stoichiometry.

No binding detected.

Single measurement.

For unlabeled protein production, recombinant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21-Gold (DE3) in LB medium. The cells were cultivated with vigorous shaking at 37°C in LB medium and were then induced with 1 mM IPTG when the culture reached an optical density OD600 of 0.6–0.8 and were incubated overnight at 21°C. For the purification of His-tagged RBM39-UHM domain RRM3, the harvested cells were resuspended in Ni-binding buffer [0.2 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer pH 7.1 and cOmplete EDTA-free protease-inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche)] and those for the GST-tagged U2AF65 construct were resuspended in PBS buffer [0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer pH 7.1 and cOmplete EDTA-free protease-inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche)]. The mixtures were disrupted by ultrasound (20 s × 10) at 0°C. The soluble mixture of RBM39 was passed over a 5 ml HisTrap Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 0.3 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 50 mM Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 pH 7.1 and eluted with an imidazole gradient (0–0.5 M). GST-tagged U2AF65-ULM constructs were purified by glutathione-affinity chromatography on a GSTrap Fast Flow 5 ml column (GE Healthcare) in PBS buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer pH 7.1) and eluted with 25 mM reduced glutathione in the same buffer.

The protein peaks were collected and dialyzed against TEV protease-cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA containing 1 mM DTT). Purification tags were cleaved by incubation of the samples with TEV protease in a 50:1(w:w) ratio overnight at 4°C. The protein samples were then purified by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 75 16/60 HiLoad gel-filtration column equilibrated with 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM TCEP, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0. The active fractions were collected and concentrated on Amicon centrifugal filters (Millipore) in 25 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0.

Selenomethionine-labeled RBM39-UHM protein was produced as described elsewhere (Van Duyne et al., 1993 ▸; Kumar, Punta et al., 2014 ▸).

Uniformly 13C,15N-labeled RBM39-UHM was expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) using M9 minimal growth medium containing 15NH4Cl (1 g l−1) and (13C6)-d-glucose (4 g l−1) as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively. Cell cultures were grown at 37°C and then induced with 1 mM IPTG when the culture reached an optical density OD600 of 0.6–0.8.

Cells were allow to grow for 16 h at 18°C and were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in extraction buffer [0.2 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 20 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 buffer pH 7.5, cOmplete EDTA-free protease-inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche)] and lysed by sonication. Following centrifugation at 20 000g for 30 min, the cleared lysate was loaded onto an HisTrap HP Ni-affinity column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer A (0.2 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 20 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 pH 7.5). The imidazole concentration was increased, first to 30 mM to remove nonspecifically bound proteins and subsequently to 500 mM to elute the target protein. TEV protease cleavage was performed overnight at room temperature and the resulting protein solution was loaded onto a desalting column (HiPrep 26/10, GE Healthcare) and eluted with buffer A. The protein fractions were then passed through a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A to remove the His-tagged TEV protease and the cleaved His tag. Fractions containing the target protein, as determined by SDS–PAGE, were pooled and loaded onto a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with NMR buffer (50 mM NaCl, 20 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 pH 6.0). The fractions containing the target protein were concentrated to 550 µl using 3 kDa cutoff centrifugal filter devices (Millipore), with the final protein concentration being approximately 1.1 mM. The NMR samples were supplemented with 5%(v/v) 2H2O, 4.5 mM NaN3.

Synthetic U2AF65 peptides with phosphorylated Tyr91 and Tyr107 were purchased from Biomatik (USA) at 95% purity and were used without additional purification.

Protein and peptide concentrations were measured with the DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad).

2.5. Protein crystallization

For crystallization, the RBM39-UHM Asn468Tyr mutant and the U2AF65-ULM (85–112) peptide were mixed in a 1:2 molar ratio and passed through a Superdex 75 16/60 HiLoad gel-filtration column in 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM TCEP, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0. The peak containing the protein complex was collected and used for crystallization trials. For crystallization trials, selenomethionine-labeled RBM39-UHM was concentrated to 19 mg ml−1 and the RBM39–U2AF65 complex was concentrated to 68 mg ml−1 in 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0. The proteins were crystallized using the nanodroplet vapor-diffusion method (Santarsiero et al., 2002 ▸) with standard JCSG crystallization protocols (Lesley et al., 2002 ▸). Drops composed of 100 nl protein solution mixed with 100 nl crystallization solution in a sitting-drop format were equilibrated against 100 µl reservoir solution at 277 K for 12–20 d prior to harvesting. The crystallization reagent consisted of 0.1 M KCl, 15% polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 5000, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0 for the RBM39–U2AF65 complex and 20% polyethylene glycol 6000, 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.0 for the RBM39-UHM domain. The mounted crystals were coated with Perfluoropolyether Cryo Oil (Hampton Research) as a cryoprotectant. Initial screening for diffraction was carried out using the Stanford Automated Mounting system (SAM; Cohen et al., 2002 ▸) at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL; Menlo Park, California, USA).

2.6. Data collection and refinement

X-ray diffraction data were collected on SSRL beamline 14-1 at a wavelength of 1.000 Å and a temperature of 100 K using a MAR 325 CCD detector.

For RBM39-UHM, data were collected at wavelengths corresponding to the high-energy remote (λ1 = 0.9537 Å) and inflection (λ2 = 0.9792 Å) points of a two-wavelength, selenium multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) experiment. X-ray diffraction data were indexed in the orthorhombic space group P212121. The data were integrated and scaled using MOSFLM (Leslie, 2006 ▸) and SCALA. The selenium substructure of RBM39-UHM was determined with SHELXD (Schneider & Sheldrick, 2002 ▸) and the MAD phases were refined with autoSHARP (Schneider & Sheldrick, 2002 ▸). Iterative automated model building was performed with ARP/wARP. Model building was performed using Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▸) and refinement was performed using REFMAC5 at a resolution of 0.95 Å with the refinement restrained against the MAD phases. X-ray data-collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Summary of crystallographic statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| RBM39-UHM (PDB code 3s6e) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| λ1 MADSe | λ2 MADSe | RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM Asn468Tyr complex (PDB code 5cxt) | |

| Data collection | |||

| Beamline | 14-1, SSRL | 14-1, SSRL | |

| Space group | P212121 | P32 | |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 44.70, b = 55.14, c = 84.60 | a = b = 127.28, c = 78.86 | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.95369 | 0.97915 | 1.000 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 28.21–0.95 | 28.22–0.98 | 39.43–2.20 |

| No. of observations | 683758 | 693051 | 275854 |

| No. of unique reflections | 131023 | 119357 | 72455 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (96.3) | 99.0 (92.3) | 99.7 (98.0) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 14.0 (1.9) | 13.0 (2.6) | 9.7 (2.1) |

| R merge on I † (%) | 6.3 (67.0) | 7.2 (70.5) | 11.6 (83.0) |

| R meas on I ‡ (%) | 6.8 (76.7) | 8.0 (80.0) | 13.3 (99.9) |

| R p.i.m. on I § (%) | 2.6 (36.4) | 3.2 (37.0) | 6.7 (52.6) |

| Model and refinement statistics | |||

| No. of reflections¶ (total) | 130918 | 72263 | |

| No. of reflections (test) | 6590 | 3629 | |

| Cutoff criterion | |F| > 0 | |F| > 0 | |

| R cryst †† (%) | 11.9 | 17.4 | |

| R free †† (%) | 13.2 | 19.0 | |

| Stereochemical parameters | |||

| Restraints (r.m.s.d. observed) | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.018 | 0.019 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.83 | 1.64 | |

| MolProbity all-atom clashscore | 4.4 | 0.9 | |

| Ramachandran plot‡‡ (%) | 98.6 [1] | 97.0 [2] | |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.5 | 1.2 | |

| Wilson B value (Å2) | 8.0 | 32.4 | |

| Average isotropic B value† (Å2) | 7.9 | 39.4 | |

| ESU based on R free ‡ (Å) | 0.018 | 0.033 | |

| No. of protein atoms | 1953 | 8618 | |

| No. of residues | 224 | 1098 | |

| No. of chains | 2 | 18 | |

| Nonprotein entities | 2 glycerol (GOL), 1 citric acid (CIT), 383 waters | 518 waters | |

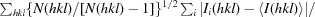

R

merge =

.

.

R

meas =

.

.

R

p.i.m (precision-indicating R

merge) =

.

.

Typically, the number of unique reflections used in refinement is slightly less than the total number that were integrated and scaled. Reflections are excluded owing to negative intensities and rounding errors in the resolution limits and the unit-cell parameters.

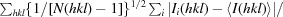

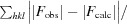

R

cryst =

, where F

calc and F

obs are the calculated and observed structure-factor amplitudes, respectively. R

free is the same as R

cryst but calculated for 5.0% of the total reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

, where F

calc and F

obs are the calculated and observed structure-factor amplitudes, respectively. R

free is the same as R

cryst but calculated for 5.0% of the total reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

This value represents the total B, which includes TLS and residual B components.

Percentage of residues in favored regions of the Ramachandran plot (the number of outliers in given in square brackets).

Estimated overall coordinate error.

For the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM complex, data were indexed in the trigonal space group P32 to 2.2 Å resolution. The data were integrated and scaled using the XDS software package (Kabsch, 2010a ▸,b ▸). Since RBM39 comprises most of the scattering material in the co-crystal, molecular replacement was used to position it in the unit cell using Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▸). The coordinates of a single subunit of RBM39 (chain A from the structure above) were used as the search model, which resulted in the positioning of six RBM39 subunits within the asymmetric unit. The six RBM39 subunits were refined using REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▸, 2011 ▸) and the resulting phases were used in ARP/wARP (Langer et al., 2008 ▸) for iterative automated tracing of three additional RBM39 subunits into the asymmetric unit. Subsequent cycles of manual rebuilding and refinement were accomplished with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸) and REFMAC5. To determine the location of the U2AF65 polypeptide, σ-weighted F o − F c and 2F o − F c electron-density maps calculated from the refined RBM39 molecular-replacement phases revealed strong difference electron density adjacent to all nine RBM39 subunits in the asymmetric unit. A polypeptide consisting of approximately 11 (Val88–Gly98) of the 28 residues of the U2AF65 construct was modeled into the densities. The crystal was partially twinned, with a twinning faction of ∼0.2, which was accounted for during refinement. Refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2 ▸.

The quality of the crystal structure was analyzed using the JCSG Quality Control server (http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/jcsg/QC/). This server verifies the stereochemical quality of the model using AutoDepInputTool (Yang et al., 2004 ▸), MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010 ▸) and WHAT IF v.5.0 (Vriend, 1990 ▸), the agreement between the atomic model and the data using SFCHECK v.4.0 (Vaguine et al., 1999 ▸) and RESOLVE, the protein sequence using ClustalW (Chenna et al., 2003 ▸) and the atom occupancies using MOLEMAN2 (Kleywegt et al., 2001 ▸). Atomic coordinates and experimental structure factors for free RBM39-UHM at 0.95 Å resolution and its complex with the U2AF65-ULM peptide at 2.2 Å resolution have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) with codes 3s6e and 5cxt, respectively. The RBM39-UHM plasmid was deposited in the PSI:Biology-Materials Repository (https://dnasu.org/DNASU/) with clone ID MmCD00545612.

2.7. NMR data acquisition

All NMR experiments were performed at 298 K. A Bruker AVANCE 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm z-gradient cryoprobe was used to record the four-dimensional APSY-HACANH, five-dimensional APSY-CBCACONH and five-dimensional APSY-HACACONH NMR experiments (Hiller et al., 2005 ▸), and a Bruker AVANCE 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a room-temperature TXI-HCN probe head was used to record the three-dimensional 15N-resolved, three-dimensional 13C(aliphatic)-resolved and three-dimensional 13C(aromatic)-resolved [1H,1H]-NOESY experiments with a mixing time of 65 ms. Proton chemical shifts were referenced to internal 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid sodium salt (DSS). The 13C and 15N chemical shifts were referenced indirectly to DSS using the absolute frequency ratios (Wishart et al., 1995 ▸). Acquisition of two-dimensional [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra for the study of interactions between RBM39 and U2AF65-ULM was carried out on a Bruker AVANCE 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 1.7 mm z-gradient room-temperature microcoil probe head.

2.8. Resonance assignments and NMR structure determinations

The resonance assignment and NMR structure determination followed the J-UNIO protocol (Serrano et al., 2012 ▸; Volk et al., 2008 ▸; Fiorito et al., 2008 ▸). Automated routines yielded 95% of the backbone assignments and 82% of the side-chain assignments. These assignments were validated and interactively extended to 96% and then used as input for UNIO-ATNOS/CANDID (Herrmann et al., 2002a ▸,b ▸) in combination with the torsion-angle dynamics algorithm CYANA 3.0 (Güntert et al., 1997 ▸). The 40 best conformers were energy-minimized in a water shell with OPALp (Luginbühl et al., 1996 ▸; Koradi et al., 2000 ▸) using the AMBER force field (Cornell et al., 1995 ▸). The best 20 of these conformers, as identified during structure validation (Serrano et al., 2012 ▸), were selected to represent the NMR structure of RBM39-UHM, and MOLMOL (Koradi et al., 1996 ▸) was used to analyze this ensemble of conformers. The atomic coordinates of the bundle of 20 conformers used to represent the solution structure of RBM39-UHM have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) with accession code 2lq5.

2.9. Isothermal titration calorimetry

The binding affinity of RBM39-UHM and U2AF65-ULM and their mutants was measured using a MicroCal Auto-iTC 200 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). To be consistent with the conditions used for crystallization, protein samples were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA. A total of 16 2.45 µl aliquots of 0.8 mM solutions of U2AF65-ULM samples were injected into 0.4 ml of a 40 µM solution of RBM39-UHM at 25°C. After correction for heats of dilution, the data were processed using the manufacturer’s software.

2.10. Computation

Multiple protein sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW. Protein–protein interaction interfaces were calculated using the PDBePISA server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa) and the PIC: Protein Interactions Calculator server (http://pic.mbu.iisc.ernet.in).

3. Results

3.1. Interactions between U2AF65 RS-ULM and endogenous RBM39 in T cells

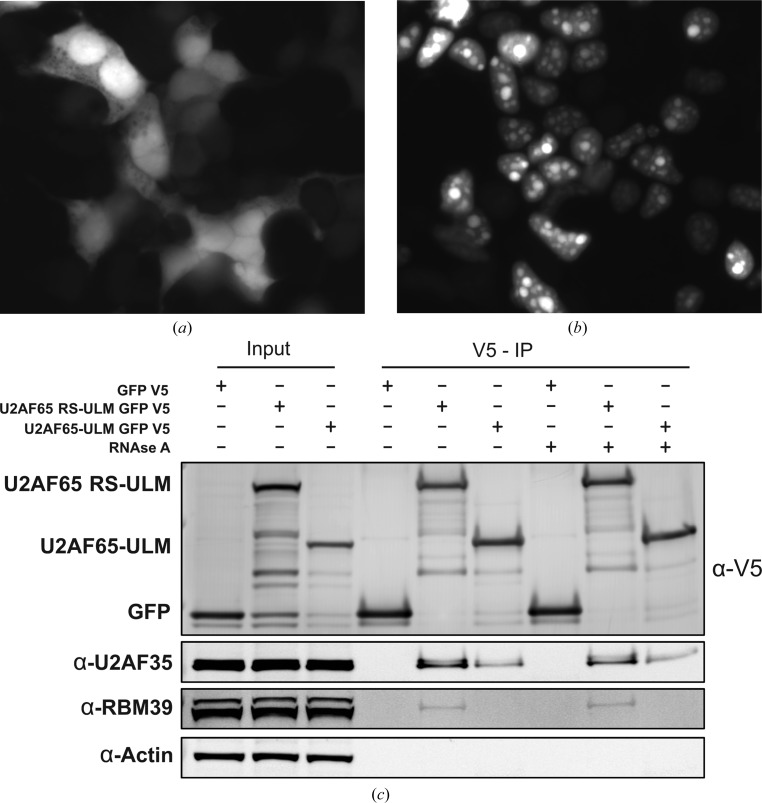

RBM39 was previously identified as a protein-interaction partner with U2AF65 (Ellis et al., 2008 ▸; Prigge et al., 2009 ▸), and was confirmed as a U2AF65 interaction partner in T cells using proteomic mass spectrometry (data not shown). Preliminary biochemistry experiments with purified domain constructs in vitro implicated the UHM domain of RBM39 and the ULM of U2AF65 as the interacting regions. To test whether the ULM domain of U2AF65 is sufficient to pull down endogenous RBM39 in vivo, 293T cells were transiently transfected with GFP-V5-tagged U2AF65-ULM constructs with or without the RS domain of U2AF65. The ULM construct exhibits both cytoplasmic and nuclear localization (Fig. 2 ▸ a). The RS-ULM shows a speckled, nuclear pattern of localization (Fig. 2 ▸ b), consistent with the role of the RS domain in conferring proper localization of U2AF65 (Gama-Carvalho et al., 2001 ▸). Lysates from the transfected cells were used in a co-immunoprecipitation assay to test whether either construct can interact with and pull down endogenous RBM39 (Fig. 2 ▸ c). Both U2AF65-ULM and U2AF65 RS-ULM constructs were able to pull down endogenous U2AF35, although the interaction was weaker with the construct lacking the RS domain. This observation suggests that the role of U2AF65-RS might not be limited to enabling proper subcellular location, but also involves engaging in additional contacts with RBM39. These results, along with previous findings (Ellis et al., 2008 ▸), provide compelling evidence that the interaction between U2AF65 and RBM39 occurs in the nucleus. Furthermore, the ability of U2AF65 RS-ULM to pull down endogenous RBM39 does not rely on the presence of RNA, as treatment with RNase A had no effect on the amount of RBM39 bound (Fig. 2 ▸ c).

Figure 2.

Interaction between endogenous RBM39 and U2AF65-ULM domain constructs in 293T cells. (a) Localization of the V5-tagged U2AF65-ULM construct in the cytoplasm. (b) Localization of the V5-tagged U2AF65 RS-ULM construct in the nucleus. (c) Immunoprecipitates from transfected 293T cells probed for interaction of U2AF65-ULM with endogenous RBM39.

3.2. NMR structure determination of RBM39-UHM and identification of the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM binding interface

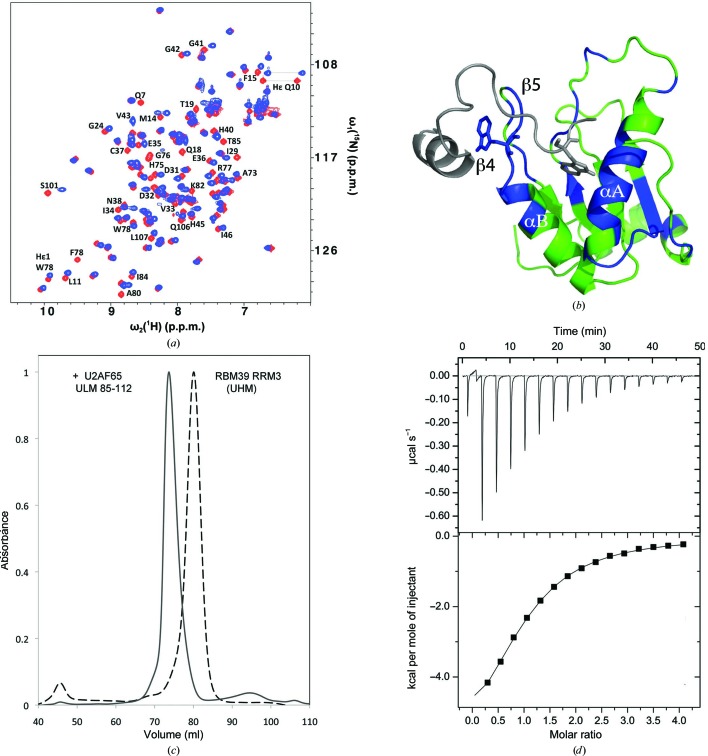

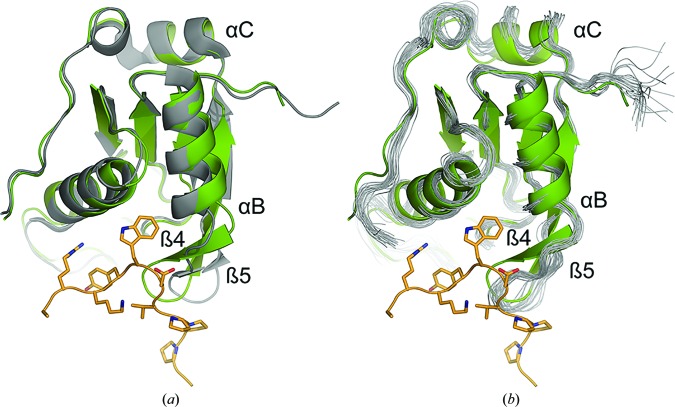

The NMR structure of RBM39-UHM was determined using the J-UNIO protocol (Serrano et al., 2012 ▸). The result is presented as a ribbon diagram in Fig. 3 ▸(b), and a bundle of 20 NMR conformers is superimposed with the corresponding crystal structures in Fig. 5(b). The statistics of the NMR structure determination (Table 3 ▸) show that a high-quality structure was obtained.

Figure 3.

Biochemical analysis of RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM interactions. (a) Superposition of the two-dimensional [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled RBM39-UHM in the absence (red) and presence (blue) of 1.3 equivalents of unlabeled U2AF65-ULM (residues 85–112). The resonances of residues with chemical shift changes of ≥0.13 p.p.m. are labeled. (b) Model of the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM complex generated by HADDOCK. The NMR structure of RBM39-UHM (color-coded as described below) was used as the input, and the U2AF65-ULM fragment (gray) was docked to it using NMR constraints derived from the chemical shift mapping. RBM39-UHM residues experiencing either large chemical shifts, line broadening and chemical shifts, or broadening beyond detection are colored blue, while those with no significant changes are colored green. The reciprocal tryptophans are shown as stick diagrams. (c) Normalized size-exclusion chromatography elution profiles of RBM39-UHM and a mixture of RBM39-UHM and U2AF65-ULM (residues 85–112) in a 1:2 molar ratio. (d) Isothermal titration calorimetry profile of solutions of RBM39-UHM and the U2AF65-ULM (85–112) peptide, showing binding with a K d of 20 µM.

Table 3. Input and calculation statistics for the NMR structure determination of RBM39-UHM in aqueous solution at pH 6.0 and T = 298 K.

Except for the top six entries, which represent the input generated for the final cycle of structure calculation with UNIO-ATNOS/CANDID and CYANA 3.0, average values and standard deviations for the 20 energy-minimized conformers are given.

| NOE upper distance limits | |

| Total | 2188 |

| Intraresidual | 458 |

| Short-range | 638 |

| Medium-range | 479 |

| Long-range | 614 |

| Dihedral angle constraints | 455 |

| Residual target function value (Å2) | 1.29 ± 0.18 |

| Residual NOE violations | |

| No. ≥0.1 Å | 14 ± 3 |

| Maximum (Å) | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| Residual dihedral angle violations | |

| No. ≥2.5° | 0 ± 1 |

| Maximum (°) | 1.63 ± 0.83 |

| AMBER energies (kcal mol−1) | |

| Total | −4039 ± 184 |

| Van der Waals | −270 ± 14 |

| Electrostatic | −4511 ± 181 |

| R.m.s.d. from the mean coordinates† (Å) | |

| Backbone (20–55, 67–112) | 0.50 ± 0.08 |

| All heavy atoms (20–55, 67–112) | 0.87 ± 0.09 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics‡ | |

| Most favored regions (%) | 78.1 |

| Additional allowed regions (%) | 20.0 |

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 1.3 |

| Disallowed regions (%) | 0.6 |

The numbers in parentheses indicate the residues for which the r.m.s.d. was calculated.

As determined by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▸).

NMR chemical shift mapping was used to identify the RBM39-UHM residues involved in the interaction with U2AF65-ULM. Initially, two U2AF65-ULM peptides, residues 85–112 and 79–142, were titrated into a solution of uniformly 15N-labeled RBM39-UHM, and changes in the signals from the amide groups of RBM39-UHM were monitored using [15N,1H]-HSQC experiments. Addition of either ULM peptide induced identical changes, which were either chemical shifts or line broadening (Fig. 3 ▸ a), and indicate that only the residues in peptide segment 85–112 are involved in binding. Based on sequence-specific polypeptide backbone resonance assignments, two main locations in RBM39-UHM were affected by ULM binding: the hairpin with an R-X-F element formed by strands β4 and β5, and segments of α-helices A and B (Fig. 3 ▸ b). This result was independently supported by the generation of a HADDOCK model (van Dijk et al., 2006 ▸) obtained using the NMR structure of RBM39 and a list of the residues experiencing either chemical shifts and/or line broadening as input (Figs. 3 ▸ a and 3 ▸ b). These results also provided a rational approach for the crystallization of the UHM–ULM complex as described below.

3.3. Structural basis of UHM–ULM specificity in the RBM39–U2AF65 complex

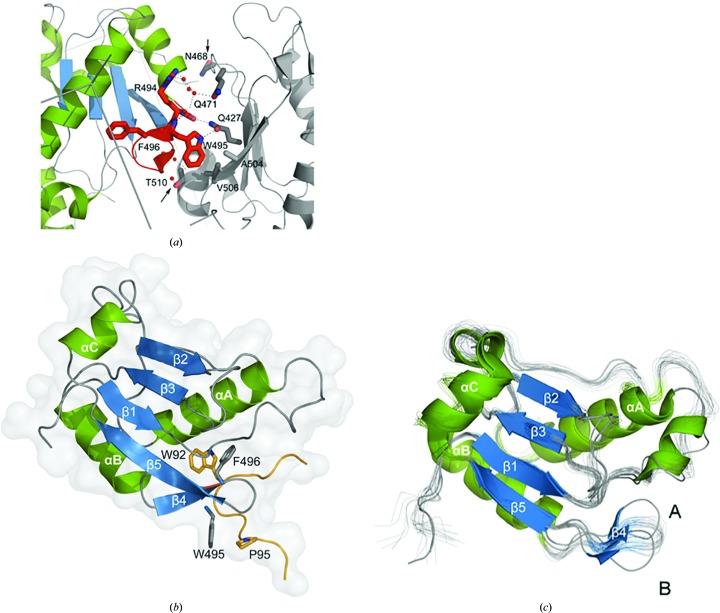

To investigate the molecular details of the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM interaction, we attempted to co-crystallize RBM39-UHM with several U2AF65-ULM peptide constructs (residues 79–142, 85–112 and 88–112) that form stable complexes, as shown for RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM (85–112) by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3 ▸ c) and ITC titration profiles (Fig. 3 ▸ d). Crystallization trials consistently produced diffraction-quality crystals, but the resulting electron-density maps contained only RBM39-UHM, with no apparent electron density for the U2AF65-ULM peptides. Two nearly identical molecules of RBM39-UHM (A and B) were present in the asymmetric unit and their Cα atoms superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 0.57 Å. Analysis of the RBM39-UHM crystal packing revealed that the ULM-binding site, as determined from NMR chemical shift mapping, was involved in multiple intermolecular crystal lattice contacts with symmetry-related RBM39-UHM molecules (Fig. 4 ▸ a).

Figure 4.

Structures of free RBM39-UHM and of RBM39-UHM bound to U2AF2-ULM. (a) Intermolecular crystal contacts between symmetry-related RBM39-UHM molecules. The amino acids of the R-X-F motif are shown in red and hydrogen bonds as dotted lines; red spheres represent water molecules. Arrows indicate the mutation sites discussed in the text (Asn468Tyr and Thr510Tyr). (b) Crystal structure of the third RRM of RBM39-UHM bound to U2AF65-ULM. β-Strands are colored blue, α-helices green and the ULM peptide yellow. The reciprocal tryptophan binding sites (Trp495 and Trp92) and the nearby residues proline (Pro95) and phenylalanine (Phe496) are shown as stick diagrams. The conserved R-X-F motif is indicated in red. (c) Structural alignment of the RBM39-UHM domain crystal structure (PDB entry 3s6e, chains A and B; both shown as cartoons) with the NMR solution structure (PDB entry 2lq5; shown in gray as a bundle of 20 conformers superimposed for minimal pairwise r.m.s.d.s relative to the mean coordinates; Table 3 ▸). The labels A and B indicate the chains in the crystal structure.

Thus, in the RBM39-UHM crystals lattice interactions effectively compete with ULM binding. In an attempt to alter the crystal packing, RBM39-UHM variants were engineered to remove lattice contacts while preserving the ULM binding surface. The RBM39-UHM Asn468Tyr and Thr510Tyr surface mutations (Fig. 4 ▸ a) retained binding affinity for the ULM (Table 1 ▸) and produced diffraction-quality RBM39–U2AF65 co-crystals (Table 2 ▸).

The crystal structure of RBM39-UHM Asn468Tyr (418–530) bound to the U2AF65–ULM (85–112) complex at 2.2 Å resolution is illustrated in Fig. 4 ▸(b). Although monomeric in solution, nine molecules of RBM39 with bound U2AF65-ULM peptides are located in the asymmetric unit. Protein–protein complexes are arranged in three clusters of three in a cloverleaf-like shape. Electron density was only observed for the polypeptide segment 88–98 of U2AF65-ULM, comprising 11 of the 28 residues of the peptide used for crystallization.

As expected, RBM39-UHM adopts the characteristic RRM-family βαββαβ fold. Residues 425–429 (β1), 461–465 (β2), 473–477 (β3) and 499–505 (β5) constitute an antiparallel β-sheet, which is sandwiched between α-helices A (442–456) and B (481–491) on one side and the C-terminal α-helix C (residues 508–514) on the other. In addition, RBM39-UHM residues 493–496 form strand β4 that extends from α-helix B and forms a β-hairpin structure with the RRM canonical strand β5 on the C-terminal side of the hairpin (Fig. 4 ▸ b).

The typical canonical RRM fold possesses two conserved ribonucleoprotein motifs, named RNP2 and RNP1, which correspond to the β1 and β3 strands, respectively (Fig. 1 ▸ c). The consensus RNP2 and RNP1 sequences are defined as V/L/I-F/Y-L/V/I-G/K-N/L-L and K/R-G-F/Y-G/A-F/V/Y-X-F/Y, respectively. However, based on the sequence and structural information, RNP2 and RNP1 of RBM39 have 423T-Q-C-F-Q-L 428 and 471Q-G-N-V-Y-V-K-C478 sequences, respectively, with almost no correspondence in amino-acid residue or type (bold residues). The side chains of Cys425, Gln427 and Ser429 in the β1 strand, His462 and Tyr464 in the β2 strand and Asn473, Tyr475 and Lys477 in the β3 strand are exposed on one surface of the RBM39-UHM β-sheet. However, the aromatic side chains of Tyr511 and Phe515 of the C-terminal α-helix C form a highly hydrophobic contact area, with the β-sheet surface shielding the potential RNA-binding site. The presence of variant RNP1 and RNP2 sequences and the tight packing of the C-terminal α-helix C against the presumed RNA-binding site (Fig. 4 ▸ b) suggest that the β-sheet in RBM39 does not interact with RNA and thus RBM39-UHM is not a canonical RRM. An additional C-terminal α-helix has also been observed in a number of other UHM proteins (U2AF65 and SPF45), which may also occlude the β-sheet surface and block RNA binding. This three-dimensional arrangement does not preclude UHM–RNA interactions through other structural elements, such as loops, as has previously been observed in ‘quasi-RRM domains’ (Singh et al., 2013 ▸).

In order to compare the free and bound forms, the structure of free RBM39-UHM was determined by both X-ray crystallography (Table 2 ▸) and NMR spectroscopy (Table 3 ▸). When the crystal and solution structures of the free RBM39-UHM domain are compared, the largest difference is a slight alteration of the β-hairpin conformation, which is likely to be owing to intermolecular interactions in the crystal (Fig. 4 ▸ c). The r.m.s.d. values calculated for the Cα atoms between the mean coordinates of the NMR structure and chains A and B of the crystal structure are 1.73 and 1.42 Å, respectively. The free and U2AF65-ULM-bound RBM39-UHM crystal structures superimpose with Cα r.m.s.d.s of 0.70 Å (PDB entry 3s6e, chain A) and 0.59 Å (PDB entry 3s6e, chain B) (Fig. 5 ▸ a). Considering that the conformation of the ULM-binding site of apo RBM39 is influenced by crystal packing, we compared the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM crystal structure with the apo RBM39-UHM solution structure (PDB entry 2lq5; Fig. 5 ▸ b). Although the conformational changes are minimal upon binding of the ULM peptide (the Cα r.m.s.d is 1.02 Å), the largest structural changes occur in the β-hairpin and in α-helix B (Figs. 5 ▸ a and 5 ▸ b).

Figure 5.

Superposition of the RBM39-UHM domain bound to the U2AF65-ULM peptide (PDB entry 5cxt, chain M; shown in green) with (a) the crystal structure of RBM39-UHM (PDB entry 3s6e, both chains shown in gray) and (b) the NMR solution structure of RBM39-UHM (PDB entry 2lq5; multiple conformers represented as ribbons in gray). The ULM peptide is shown in yellow.

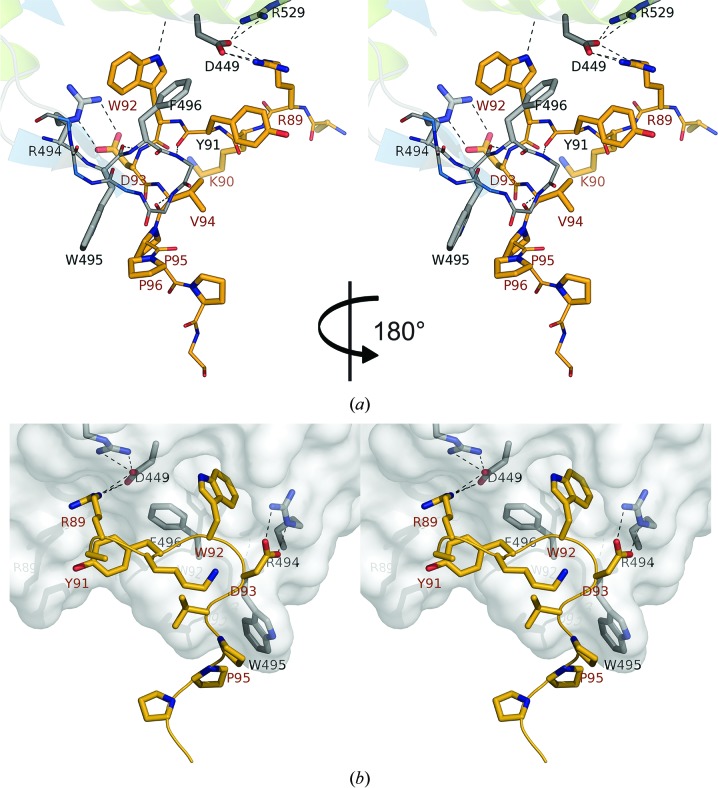

Eight residues of U2AF65-ULM (Arg89–Pro96) directly contact RBM39-UHM (Figs. 1 ▸ c, 6 ▸ a and 6 ▸ b). The interaction with U2AF65 mainly involves the conserved UHM R-X-F motif (residues Arg494, Trp495 and Phe496), which is located on the side of the β-hairpin (Figs. 6 ▸ a and 6 ▸ b), which is in agreement with NMR chemical shift mapping data for ULM binding (Figs. 3 ▸ a and 3 ▸ b). A number of hydrophobic interactions are involved in the ULM–UHM binding interface. The side chain of the conserved Trp92 in U2AF65 inserts into a hydrophobic pocket formed by α-helices A and B and strand β4 (Figs. 6 ▸ a and 6 ▸ b). Trp495 of RBM39-UHM is engaged in hydrophobic interactions with the ULM C-terminal prolines Pro95 and Pro96. The indole ring of Trp92 of U2AF65 is also involved in π-stacking interactions with Phe496 in the R-W-F motif, which is located on the inner side of the β–β hairpin, and cation–π interactions with the guanidinium moiety of Arg494 of RBM39. In addition to the hydrophobic stacking interactions, intermolecular UHM–ULM interactions are further stabilized through hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. The RBM39 backbone amide H atoms of Ala497 and Gly498 and carbonyl O atoms of Tyr91and Val94 of U2AF65 form a network of hydrogen bonds with the β-hairpin, while the NE1 amino group of the Trp92 indole ring is hydrogen-bonded to the main-chain carbonyl of Asp449 in α-helix A.

Figure 6.

Stereoview of the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM protein–protein interaction interface (PDB entry 5cxt, chains M and N). The U2AF65-ULM peptide is shown in yellow and RBM39-UHM is shown as gray sticks and color-coded by atom type (red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen). (a) Front view. (b) Surface view of the complex rotated to 180° relative to the perspective of (a). Dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds.

Arg89 of U2AF65 forms electrostatic contacts with Asp449 in α-helix A of RBM39, and complementary electrostatic interactions are found between Arg494 of RBM39 and Asp93 of U2AF65. Lys90 and Tyr91 of U2AF65 are solvent-exposed and do not contact RBM39-UHM. The reciprocal Trp92 and Trp495 interactions schematically constitute lock-and-key interactions, while the Arg494–Asp93 and Asp449–Arg89 salt bridges provide additional latches to further stabilize the interaction (Figs. 6 ▸ a and 6 ▸ b).

The binding affinity of RBM39 for U2AF65 was measured using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Wild-type RBM39-UHM (RRM3) binds U2AF65-ULM with a K d of 20 µM (Fig. 3 ▸ d, Table 1 ▸), as calculated for a 1:1 binding stoichiometry, while RRM1 and RRM2 exhibit no measureable affinity for the ULM (Table 1 ▸). To probe the individual contributions of specific residues to the UHM–ULM interaction, point mutations were introduced into the RBM39-UHM domain. ITC binding assays with RBM39-UHM harboring either Asp449Trp or Trp495Ala mutations (Table 1 ▸) show that these mutations abolish the binding of RBM39 to U2AF65-ULM.

It has been suggested that phosphorylation of serines and threonines in ULM motifs regulates their association with UHMs (Selenko et al., 2003 ▸). No phosphorylation has been reported for any serine or threonine residues located in the U2AF65-ULM sequence, but Tyr91 and Tyr107 still remain as potential phosphorylation sites. While the replacement of the conserved Asp449 or Trp495 residues in RBM39 abolishes U2AF65 binding, ITC analysis of RBM39 binding by peptides phosphorylated at either Tyr91 or Tyr107 revealed that the binding interactions were reduced by only a factor of two (Table 1 ▸), suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation does not play a significant role in mediating this interaction.

4. Discussion

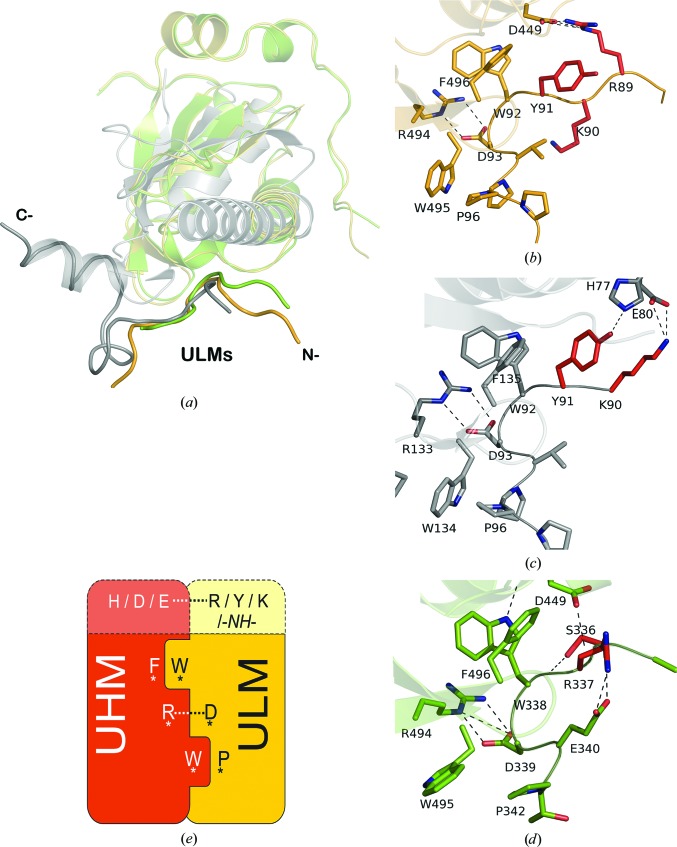

The structural studies of the RBM39–U2AF65 complex show that the binding interface involves portions of the ULM domain of U2AF65 and the UHM domain of RBM39. Comparison of the crystal structures of RBM39 bound to different ULM motifs of U2AF65 and SF3b155 with the structures of RBM39 and U2AF35 UHMs bound to an identical U2AF65 ULM peptide revealed a set of common elements as well as a set of discriminating elements. Superposition of the RBM39–U2AF65 complex with the U2AF35–U2AF65 and RBM39–SF3b155 complexes results in Cα r.m.s.d values of 0.64 and 1.14 Å, respectively (Fig. 7 ▸ a), and the three complexes (Figs. 7 ▸ b, 7 ▸ c and 7 ▸ d) exhibit the characteristic tryptophan-mediated lock-and-key interactions (Kielkopf et al., 2001 ▸; Loerch et al., 2014 ▸). In spite of this shared recognition element, the binding affinities for the other reported UHM–ULM complexes vary over four orders of magnitude: U2AF35–U2AF65, K d = 1.7–135 nM (Corsini et al., 2007 ▸; Kielkopf et al., 2001 ▸); RBM39–SF3b155, K d = 2.4 µM (Loerch et al., 2014 ▸); SPF45–SF3b155, K d = 1.1 µM (Corsini et al., 2007 ▸); RBM39–U2AF65, K d = 20 µM (this study).

Figure 7.

Superposition of the structures of the UHM–ULM complexes: (a) RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM (yellow; PDB entry 5cxt), U2AF35-UHM–U2AF65-ULM (gray; PDB entry 1jmt), RBM39-UHM–SF3b155-ULM (green; PDB entry 4oz1). UHM domains are shown as ribbon representations and ULM peptides are represented as tubes in the corresponding colors. (b)–(d) Details of UHM–ULM molecular recognition in the RBM39–U2AF65 (b), U2AF35–U2AF65 (c) and RBM39–SF3b155 (d) complexes. C atoms are colored as in (a), O atoms red and N atoms blue. C atoms of nonconserved N-terminal residues are colored red. Residues in (d) are numbered according to RBM39 isoform a for the reader’s convenience. Dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds. (e) Schematic representation of the ‘knob-into-hole’ UHM–ULM interaction mode. Conserved amino acids are labeled with asterisks. Nonconserved residues next to Trp92 in ULM and their interacting residues in UHM are shown on top in lighter tones.

In the three complexes, the hydrophobic stacking interactions involving conserved phenylalanine, tryptophan and proline residues and the C-terminal arginine–aspartic acid salt bridges are essentially identical, as shown in Figs. 7 ▸(b)–7 ▸(e). However, there are differences in the neighboring region for the interactions of RBM39 with the ULMs from SF3b155 and U2AF65. Asp449 RBM39, which forms a salt bridge with Arg89 of U2AF65 in the RBM39–U2AF65 complex (Fig. 7 ▸ b) is hydrogen-bonded to the amino group of the main chain of Arg337 in the U2AF35–SF3b155-ULM complex (Fig. 7 ▸ d). Tyr91 and Lys90 of U2AF65 are exposed to the solvent in the RBM39–U2AF65 complex (Fig. 7 ▸ b), but are hydrogen-bonded to His77 and Glu80 of U2AF65 in the U2AF35–U2AF65 complex (Fig. 7 ▸ c). Considering the high similarity in the tryptophan-mediated lock-and-key interactions of the three complexes, differences in the affinities could be the result of additional contacts involving the neighboring U2AF65-ULM amino-acid segment GFEHITPMQYKAMQA, which forms a short helix in the U2AF65–U2AF35 complex, appears to be disordered in RBM39–U2AF65 and has no X-ray-observable counterpart in the RBM39–SF3b155 complex (Fig. 7 ▸ a).

The micromolar affinity of RBM39-UHM for the U2AF65-ULM and SF3b155-ULM peptides is significantly lower than that of U2AF65-ULM for U2AF35-UHM. A similar transient weak UHM–ULM interaction has been observed for the U2AF65–SF1 complex, where the replacement of SF1 by SF3b155 is involved in recruitment of the U2 snRNP in splicing complex A (Gozani et al., 1998 ▸; Rutz & Séraphin, 1999 ▸). These weak interactions are likely to be functionally important during the assembly of splicing complexes, and there may be transient interactions between various UHM–ULM partners prior to assembly of the final and more thermodynamically stable U2AF65–U2AF35 complex at the 3′ splice site. Given the similarity of the three interfaces observed to date, it is not possible to discern the structural basis for the different thermodynamic stabilities of the interfaces, and there may well be a complex mixture of overlapping specificities that are functionally important for binding the entire set of UHM–ULM protein combinations. The specificities may be further modulated by RNA binding or by cooperative binding with other splicing factors or components of the splicing machinery.

Strategies for splicing regulation include cell-specific expression of factors, intracellular localization and post-translational protein modifications. While U2AF65 is a constitutive splicing factor that is expressed in all cells, RBM39 shows a more restricted tissue distribution, with expression mainly in immune system-associated cells, uterus, thyroid and pineal gland cells. Both the U2AF65 and RBM39 proteins are primarily localized in the nucleus and nuclear speckles, where there is the opportunity to compete for binding to other UHM- and ULM-containing proteins. While our data suggest that association between RBM39 and U2AF65 is not modulated by tyrosine phosphorylation of the ULM, it remains possible that phosphorylation of distal sites of either protein can modulate the association of these two proteins in cells. RBM39 binding to U2AF65 might be essential in the selective recognition of weak (Py)-tracts or for delivery of U2AF65 to the splice site. The one specific function attributed to RBM39 in splicing is to promote the inclusion of the pseudoexons by interfering with PTB1 repression (Nordin et al., 2012 ▸). RBM39 has also been characterized as a transcriptional co-activator, suggesting a possible role for RBM39 in coupling of transcription and alternative splicing.

The structure of the RBM39-UHM–U2AF65-ULM complex therefore leads to a better understanding of how binding specificity is mediated by particular structural features in a number of homologous UHM–ULM interactions, including the U2AF65–U2AF35 and RBM39–SF3b155 complexes. The RBM39–U2AF65 complex provides an opportunity to identify both common and unique elements of recognition in the intricate molecular network of UHM–ULM interaction. The multiple possible interactions between UHM- and ULM-containing proteins in the cell provide possible tissue-specific or RNA-specific tuning of splicing. In this context, the specific functional role of the RBM39–U2AF65 interaction in various cell types remains to be elucidated. To this end, our structure-based analysis provides a platform for the design of mutations in ULM and UHM to serve as molecular probes of their specific role in the regulation of splicing in vivo.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: RBM39-UHM, crystal structure, 3s6e

PDB reference: NMR structure, 2lq5

PDB reference: crystal structure of complex with U2AF65-ULM, 5cxt

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the JCSG high-throughput structural biology pipeline for their contribution to this work. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Protein Structure Initiative through a PSI:Biology Partnership award (U01 GM094653 to JRW and DRS) and a PSI:Biology Center for High-Throughput Structure Determination award (U54 GM094586 to IAW and the JCSG). Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bangur, C. S., Switzer, A., Fan, L., Marton, M. J., Meyer, M. R. & Wang, T. (2002). Oncogene, 21, 3814–3825. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Black, D. L. (2003). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 291–336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blencowe, B. J. (2000). Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 106–110. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Burge, C. B., Tuschl, T. H. & Sharp, P. A. (1999). The RNA World, 2nd ed., edited by R. F. Gesteland, T. R. Cech & J. F. Atkins, pp. 525–560. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Cazalla, D., Newton, K. & Cáceres, J. F. (2005). Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2969–2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chai, Y., Liu, X., Dai, L., Li, Y., Liu, M. & Zhang, J. Y. (2014). Tumour Biol. 35, 6311–6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, V. B., Arendall, W. B., Headd, J. J., Keedy, D. A., Immormino, R. M., Kapral, G. J., Murray, L. W., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chenna, R., Sugawara, H., Koike, T., Lopez, R., Gibson, T. J., Higgins, D. G. & Thompson, J. D. (2003). Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3497–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A. E., Ellis, P. J., Miller, M. D., Deacon, A. M. & Phizackerley, R. P. (2002). J. Appl. Cryst. 35, 720–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cornell, W. D., Cieplak, P., Bayly, C. I., Gould, I. R., Merz, K. M., Ferguson, D. M., Spellmeyer, D. C., Fox, T., Caldwell, J. W. & Kollman, P. A. (1995). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197.

- Corsini, L., Bonnal, S., Bonna, S., Basquin, J., Hothorn, M., Scheffzek, K., Valcárcel, J. & Sattler, M. (2007). Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 620–629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Corsini, L., Hothorn, M., Stier, G., Rybin, V., Scheffzek, K., Gibson, T. J. & Sattler, M. (2009). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dijk, A. D. J. van, Kaptein, R., Boelens, R. & Bonvin, A. M. J. J. (2006). J. Biomol. NMR, 34, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dowhan, D. H., Hong, E. P., Auboeuf, D., Dennis, A. P., Wilson, M. M., Berget, S. M. & O’Malley, B. W. (2005). Mol. Cell, 17, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dutta, J., Fan, G. & Gélinas, C. (2008). J. Virol. 82, 10792–10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ellis, J. D., Llères, D., Denegri, M., Lamond, A. I. & Cáceres, J. F. (2008). J. Cell Biol. 181, 921–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fiorito, F., Herrmann, T., Damberger, F. F. & Wüthrich, K. (2008). J. Biomol. NMR, 42, 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gama-Carvalho, M., Carvalho, M. P., Kehlenbach, A., Valcarcel, J. & Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2001). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13104–13112. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gozani, O., Potashkin, J. & Reed, R. (1998). Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4752–4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Graveley, B. R. (2000). RNA, 6, 1197–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Güntert, P., Mumenthaler, C. & Wüthrich, K. (1997). J. Mol. Biol. 273, 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Guth, S., Martínez, C., Gaur, R. K. & Valcárcel, J. (1999). Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8263–8271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, T., Güntert, P. & Wüthrich, K. (2002a). J. Mol. Biol. 319, 209–227. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, T., Güntert, P. & Wüthrich, K. (2002b). J. Biomol. NMR, 24, 171–189. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hiller, S., Fiorito, F., Wüthrich, K. & Wider, G. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 10876–10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huang, G., Zhou, Z., Wang, H. & Kleinerman, E. S. (2012). Cancer, 118, 2106–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Imai, H., Chan, E. K. L., Kiyosawa, K., Fu, X.-D. & Tan, E. M. (1993). J. Clin. Invest. 92, 2419–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010a). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010b). Acta Cryst. D66, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kent, O. A., Reayi, A., Foong, L., Chilibeck, K. A. & MacMillan, A. M. (2003). J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50572–50577. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kielkopf, C. L., Lücke, S. & Green, M. R. (2004). Genes Dev. 18, 1513–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kielkopf, C. L., Rodionova, N. A., Green, M. R. & Burley, S. K. (2001). Cell, 106, 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kleywegt, G., Zou, J., Kjeldgaard, M. & Jones, T. (2001). International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. F, edited by M. G. Rossmann & E. Arnold, pp. 353–356. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Klock, H. E., Koesema, E. J., Knuth, M. W. & Lesley, S. A. (2008). Proteins, 71, 982–994. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Konarska, M. M. & Query, C. C. (2005). Genes Dev. 19, 2255–2260. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M. & Güntert, P. (2000). Comput. Phys. Commun. 124, 139–147.

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M. & Wüthrich, K. (1996). J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P. P., Emechebe, U., Smith, R., Franklin, S., Moore, B., Yandell, M., Lessnick, S. L. & Moon, A. M. (2014). Elife, 3, e02805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A., Punta, M., Axelrod, H. L., Das, D., Farr, C. L., Grant, J. C., Chiu, H.-J., Miller, M. D., Coggill, P. C., Klock, H. E., Elsliger, M. A., Deacon, A. M., Godzik, A., Lesley, S. A. & Wilson, I. A. (2014). Protein Sci. 23, 1380–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Langer, G., Cohen, S. X., Lamzin, V. S. & Perrakis, A. (2008). Nature Protoc. 3, 1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291.

- Lesley, S. A. et al. (2002). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 11664–11669.

- Leslie, A. G. W. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Loerch, S., Maucuer, A., Manceau, V., Green, M. R. & Kielkopf, C. L. (2014). J. Biol. Chem. 289, 17325–17337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luginbühl, P., Güntert, P., Billeter, M. & Wüthrich, K. (1996). J. Biomol. NMR, 8, 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lynch, K. W. (2004). Nature Rev. Immunol. 4, 931–940. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lynch, K. W. & Maniatis, T. (1996). Genes Dev. 10, 2089–2101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manceau, V., Swenson, M., Le Caer, J.-P., Sobel, A., Kielkopf, C. L. & Maucuer, A. (2006). FEBS J. 273, 577–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Markovtsov, V., Nikolic, J. M., Goldman, J. A., Turck, C. W., Chou, M.-Y. & Black, D. L. (2000). Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7463–7479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mercier, I. et al. (2009). Am. J. Pathol. 174, 1172–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mercier, I., Gonzales, D. M., Quann, K., Pestell, T. G., Molchansky, A., Sotgia, F., Hulit, J., Gandara, R., Wang, C., Pestell, R. G., Lisanti, M. P. & Jasmin, J. F. (2014). Cell Cycle, 13, 1256–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Merendino, L., Guth, S., Bilbao, D., Martínez, C. & Valcárcel, J. (1999). Nature (London), 402, 838–841. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mollet, I., Barbosa-Morais, N. L., Andrade, J. & Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2006). FEBS J. 273, 4807–4816. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moore, M. J., Wang, Q., Kennedy, C. J. & Silver, P. A. (2010). Cell, 142, 625–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nordin, A., Larsson, E. & Holmberg, M. (2012). Hum. Mutat. 33, 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Page-McCaw, P. S., Amonlirdviman, K. & Sharp, P. A. (1999). RNA, 5, 1548–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Prigge, J. R., Iverson, S. V., Siders, A. M. & Schmidt, E. E. (2009). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1789, 487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rutz, B. & Séraphin, B. (1999). RNA, 5, 819–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Santarsiero, B. D., Yegian, D. T., Lee, C. C., Spraggon, G., Gu, J., Scheibe, D., Uber, D. C., Cornell, E. W., Nordmeyer, R. A., Kolbe, W. F., Jin, J., Jones, A. L., Jaklevic, J. M., Schultz, P. G. & Stevens, R. C. (2002). J. Appl. Cryst. 35, 278–281.

- Schneider, T. R. & Sheldrick, G. M. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Selenko, P., Gregorovic, G., Sprangers, R., Stier, G., Rhani, Z., Krämer, A. & Sattler, M. (2003). Mol. Cell, 11, 965–976. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Serrano, P., Pedrini, B., Mohanty, B., Geralt, M., Herrmann, T. & Wüthrich, K. (2012). J. Biomol. NMR, 53, 341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S., Falick, A. M. & Black, D. L. (2005). Mol. Cell, 19, 485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sillars-Hardebol, A. H., Carvalho, B., Beliën, J. A., de Wit, M., Delis-van Diemen, P. M., Tijssen, M., van de Wiel, M. A., Pontén, F., Meijer, G. A. & Fijneman, R. J. (2012). Cell. Oncol. 35, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sillars-Hardebol, A. H., Carvalho, B., Tijssen, M., Belien, J. A., de Wit, M., Delis-van Diemen, P. M., Ponten, F., van de Wiel, M. A., Fijneman, R. J. & Meijer, G. A. (2012). Gut, 61, 1568–1575. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Singh, M., Choi, C. P. & Feigon, J. (2013). RNA Biol. 10, 353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Srebrow, A. & Kornblihtt, A. R. (2006). J. Cell Sci. 119, 2635–2641. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Su, A. I., Wiltshire, T., Batalov, S., Lapp, H., Ching, K. A., Block, D., Zhang, J., Soden, R., Hayakawa, M., Kreiman, G., Cooke, M. P., Walker, J. R. & Hogenesch, J. B. (2004). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 6062–6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vaguine, A. A., Richelle, J. & Wodak, S. J. (1999). Acta Cryst. D55, 191–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Van Duyne, G. D., Standaert, R. F., Karplus, P. A., Schreiber, S. L. & Clardy, J. (1993). J. Mol. Biol. 229, 105–124. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Venables, J. P. (2006). Alternative Splicing in Cancer. Trivandrum: Transworld Research Network.

- Volk, J., Herrmann, T. & Wüthrich, K. (2008). J. Biomol. NMR, 41, 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vriend, G. (1990). J. Mol. Graph. 8, 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D., Bigam, C., Yao, J., Abildgaard, F., Dyson, H., Oldfield, E., Markley, J. & Sykes, B. (1995). J. Biomol. NMR, 6, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu, S., Romfo, C. M., Nilsen, T. W. & Green, M. R. (1999). Nature (London), 402, 832–835. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang, H., Guranovic, V., Dutta, S., Feng, Z., Berman, H. M. & Westbrook, J. D. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 1833–1839. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zorio, D. A. & Blumenthal, T. (1999). Nature (London), 402, 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: RBM39-UHM, crystal structure, 3s6e

PDB reference: NMR structure, 2lq5

PDB reference: crystal structure of complex with U2AF65-ULM, 5cxt