Until recently, the United Nations, development practitioners, and academics unanimously labeled polygyny a harmful cultural practice for child health. Lawson et al. (1) reassess the association between polygyny and child health using data from 56 Tanzanian villages. Their study suggests that children coresiding with their polygynous father tend to be better off in terms of weight-for-height, a measure of wasting, compared with children of monogamous fathers.

The study’s claim that child health is positively or not correlated with polygyny is not fully supported by the data for four main reasons:

First, weight-for-height is a short-term indicator of child health that accounts for sickness spells and short-lived shocks (2). The finding that polygyny (among some ethnic groups) has a “positive” effect on wasting should be interpreted carefully. Opting for polygyny permanently affects the per capita distribution of household assets. When analyzing the impact of permanent demographic decisions on child health, measures of long-term accumulated health, such as height-for-age, are more suitable (3).

Second, across models Lawson et al. (1) tend to find a negative correlation with the cumulative, long-term indicator of child growth. Height-for-age is systematically and negatively correlated with polygyny both at the individual and the village levels. In most specifications the effect is imprecisely estimated, which may be attributed to the small sample size. The moderately sized, negative, yet insignificant estimate [β = −0.07, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.20; 0.06, P > 0.1] found in the main specification is in line with estimates based on large sample evidence. Pooling African demographic and health surveys and assessing them at the micro level using fixed- and mixed-effect models, Wagner and Rieger (4) detected a statistically equal, significantly negative effect (β = −0.09, 95% CI = −0.12; −0.06, P < 0.01).

Third, weight-for-height should be interpreted like a ratio in that the separate effects of height and weight on polygyny are conflated. Even if both child weight and height are negatively correlated with polygyny, which is suggested by existing studies (4), the “ratio”—as expressed in weight-for-height—can mechanically show a positive or insignificant effect.

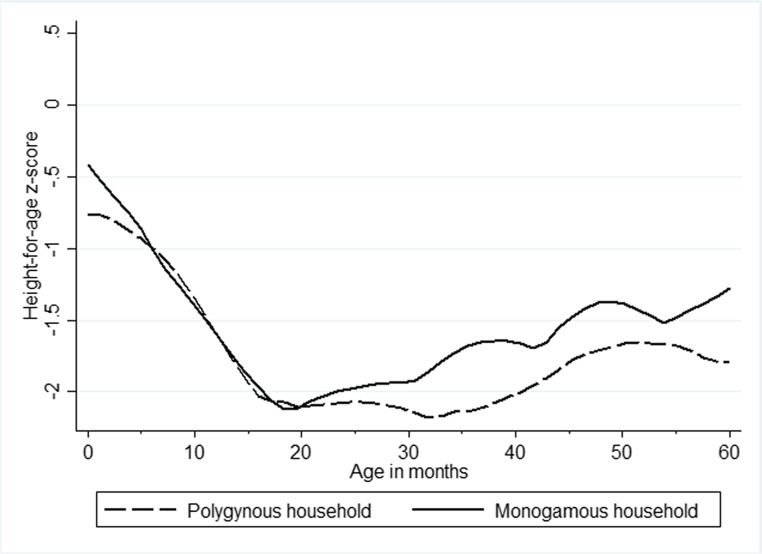

Fourth, it is well known that children across Africa are born with relatively similar height and weight, yet the adverse effects of resource-poor settings, as well as maternal conditions for child growth, magnify with age (5). In other words, being born into a polygynous household is not the same as growing up in a polygynous household. The models should take into account such age heterogeneities resulting in growth faltering (as presented in Table 1, where we split the sample at the median child age, and Fig. 1, which presents a nonparametric plot of the age profiles by marital status).

Table 1.

Multilevel regression predicting height-for-age z-scores for the full sample and by age group

| Sample | Height-for-age z-score [β (95% CIs)] | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| All children [compare with table S3 in Lawson et al. (1)] | Children ≥ 30 mo | Children < 30 mo | Children ≥ 30 mo | Children < 30 mo | |

| Household type: Polygynous (reference: monogamous) | −0.07 | −0.21** | 0.00 | −0.16* | 0.06 |

| (−0.20; 0.06) | (−0.38; −0.05) | (−0.19; 0.20) | (−0.33; 0.01) | (−0.14; 0.26) | |

| Child age (mo) | −0.09*** | 0.07 | −0.18*** | 0.06 | −0.18*** |

| (−0.10; −0.07) | (−0.03; 0.16) | (−0.22; −0.14) | (−0.03; 0.15) | (−0.21; −0.14) | |

| Child age (mo2) | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** | 0.00 | 0.00*** |

| (0.00; 0.00) | (-0.00; 0.00) | (0.00; 0.01) | (-0.00; 0.00) | (0.00; 0.01) | |

| Child sex (reference: boy) | 0.13** | 0.05 | 0.19** | 0.05 | 0.19** |

| (0.02; 0.24) | (−0.09; 0.19) | (0.03; 0.36) | (−0.10; 0.19) | (0.02; 0.35) | |

| Age of household head (y) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (−0.00; 0.01) | (−0.00; 0.01) | (−0.00; 0.01) | (−0.00; 0.01) | (−0.00; 0.01) | |

| Season: Hunger (reference: not hunger) | −0.37*** | −0.36** | −0.36*** | −0.31** | −0.34*** |

| (−0.62; −0.12) | (−0.64; -0.08) | (−0.62; −0.11) | (−0.55; −0.07) | (−0.58; −0.10) | |

| Polygyny prevalence | 0.00 | 0.01 | |||

| (−0.01; 0.02) | (−0.01; 0.02) | ||||

| Annual rainfall | 0.01** | 0.01 | |||

| (0.00; 0.02) | (−0.00; 0.02) | ||||

| Percent nonzero education | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | |||

| (0.00; 0.02) | (0.00; 0.02) | ||||

| Distance to capital | 0.00 | −0.01* | |||

| (−0.01; 0.00) | (−0.01; 0.00) | ||||

| Observations | 2,704 | 1,325 | 1,379 | 1,325 | 1,379 |

Column 1 replicates Lawson et al. (1). Columns 2 and 3 present estimates for children older and younger than 30 mo (split at the sample median of age to ensure balanced statistical power). Adverse effects of polygyny are concentrated among the older children. Qualitatively similar age patterns emerge when controlling for village-level covariates in columns 4 and 5, as well as village dummies (unreported). All models include random effects at the village level and an intercept. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Statistically significant estimates at P > 0.1 are in bold.

Fig. 1.

Age-profiles of height-for-age z-scores. Unconditional, flexible plots of z-scores across age groups for children living in polygamous and monogamous households. In both groups there is evidence of deteriorating z-scores as children grow older. These cross-sectional patterns are suggestive of growth faltering, in line with previous large-scale microstudies (5). Starting at the age of 20 mo, children residing in monogamous households show relative faster signs of recovery. These patterns are in line with lower z-scores among polygynous children in Table 1. Smoothed means by local polynomial regression using the lpoly command in STATA 13.

We fully agree with Lawson et al. (1) that labeling polygyny a unequivocally harmful cultural practice neglects the historical and cultural relevance of polygyny. A more agnostic approach is needed in this literature. Additional evidence could be collected about cowives and inheritance conflicts and longitudinal nutritional and educational outcomes for children of polygynous families to gauge whether polygyny is really harmful for children in the long run.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lawson DW, et al. No evidence that polygynous marriage is a harmful cultural practice in northern Tanzania. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(45):13827–13832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507151112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishman SM, et al. Childhood and maternal underweight. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors. WHO; Geneva: 2004. pp. 39–161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duflo E. Child health and household resources in South Africa: Evidence from the old age pension program. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90(2):393–398. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner N, Rieger M. Polygyny and child growth: Evidence from twenty-six African countries. Fem Econ. 2015;21(2):105–130. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieger M, Trommlerová SK. Age-specific correlates of child growth. Demography. 2016;53(1):241–267. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0449-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]