Abstract

HIV-1 causes a progressive impairment of immune function. HIV-2 is a naturally attenuated form of HIV and HIV-2 patients display a slow-progressing disease. The leading hypothesis for the difference in disease phenotype between HIV-1 and HIV-2 is that more efficient T cell-mediated immunity allows for immune-mediated control of HIV-2 infection, similar to that observed in the minority of HIV-1-infected long-term non progressors. Understanding how HIV-1 and HIV-2 differentially influence the immune function may highlight critical mechanisms determining disease outcome.

We investigated the effects of exposing primary human peripheral blood cells to HIV-1 or HIV-2 in vitro. HIV-2 induced a gene expression profile distinct from HIV-1, characterized by reduced type I interferon (IFN), despite similar up-regulation of IFN-stimulated genes and viral restriction factors. HIV-2 favoured plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) differentiation into cells with an antigen-presenting cells (APC) phenotype rather than interferon-α-producing cells (IPC). HIV-2, but not HIV-1, inhibited IFN-α production in response to CpG-A.

The balance between pDC maturation into IPC or development of an APC phenotype differentiates the early response against HIV-1 and HIV-2. We propose that divergent paths of pDC differentiation driven by HIV-1 and HIV-2 cause the observed differences in pathogenicity between the two viruses.

Introduction

Two types of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have been described, HIV-1 and HIV-2. Both viruses infect and replicate in CD4-expressing cells, but they differ in evolutionary origin and disease progression rate.

HIV-1 originally derived from the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) which infects chimpanzees (SIVCPZ). HIV-1 is the causative agent of AIDS in the current global pandemic, a progressive disease characterized by high plasma viral loads and low CD4 counts. HIV-1 causes an early defect in cellular immune responses during acute infection, epitomized by a rapid decline in CCR5+ CD4+ mucosal T cells and loss of IL-2 secretion by CD4+ T cells, from which the immune system fails to recover (1). Immune alterations during HIV-1 infection are not restricted to T cell depletion. Dysregulation in dendritic cell subsets also occurs during acute HIV-1 infection and is protracted throughout the course of disease (2). Thus, early events in virus-host interactions are likely to critically contribute to disease progression. In particular, HIV-1 may induce a rapid dysregulation of innate immune responses, promoting the excessive and prolonged production of type I interferon (IFN-I) (3-5) and activation of the immunoregulatory enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (3, 6). These early-occurring immune alterations have been suggested to prevent the development of efficient and long-lasting antiviral adaptive T cell responses. In addition, increasing evidence shows that early inhibition of viral activity by antiretroviral treatment preserves immune function and favours long term control of infections (7-11).

HIV-2 originated from SIV infection of sooty mangabeys (SIVSM), and is a naturally attenuated form of HIV. HIV-2 is less transmissible than HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection rates are progressively declining and are largely confined to West Africa (12). At the amino acid level, HIV-1 and HIV-2 share approximately 60% identity in the Gag and Pol proteins, and only 30-40% identity in the Env coding regions (13).

HIV-2 infection is characterized by a slow rate of disease progression, with lower plasma viral loads and a slower rate of CD4+ T cell decline (14, 15). Thus, the vast majority of HIV-2 patients display a phenotype comparable to that of HIV-1-infected long-term non-progressors (LTNP). However, the expression of markers of immune activation is similar in HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected individuals with comparable levels of CD4 depletion, despite the distinct rates of CD4 decline (16). In addition, similar reductions in circulating myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (mDC and pDC, respectively) are observed in HIV-1+ and HIV-2+ patients with comparable degrees of peripheral CD4 T cell depletion and T cell activation (17, 18). Upon progression to AIDS, clinical manifestations in HIV-2 patients are indistinguishable from HIV-1 infection (19). Interestingly, proviral DNA levels are similar in HIV-1 and HIV-2 patients, suggesting that the slower progression of HIV-2 disease is not due to a difference in the rate of infection (20).

HIV-2 has been studied as a model of immunologically controlled HIV infection, based on evidence suggesting that HIV-2 infection is associated with an efficient cell-mediated immune response. However, studies investigating immune responses against HIV-2 have shown conflicting results. When comparing asymptomatic HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected patients, some reports showed no differences in the frequencies of HIV-specific T cells or the breadth of responses (21-23). However, Duvall and colleagues (2006) reported enhanced HIV-specific memory CD4+ T cell responses in asymptomatic HIV-2 compared to HIV-1 patients (24). In particular, HIV-2+ individuals preserved the ability to secrete IL-2 (25) and displayed an increased frequency of polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (26). A recent study comparing HIV-2 progressors and HIV-2 controllers concluded that the association between the magnitude of HIV-2 Gag-specific T cell responses and undetectable viral loads is mainly due to the CD8+ T cell response (27). Furthermore, CD8+ T cell polyfunctionality is associated with viral control, similar to HIV-1 controllers. Nonetheless, it is unclear whether an enhanced cellular immune response is the cause or consequence of low levels of circulating virus (28). In addition, studies investigating antiviral immune response in HIV-1 and HIV-2 chronically infected patients cannot provide any information on the differences in early virus-host interactions and their contribution to shaping the phenotype of chronic disease.

In this study, we directly compared the effects of HIV-1 and HIV-2 on primary human cells from healthy uninfected humans with no previous exposure to either of the two viruses. We tested the hypothesis that acute HIV-2 exposure induces an innate immune profile which is qualitatively different from HIV-1, and associated with reduced activation of immunosuppressive mechanisms, which in turn favours the development of efficient T cell response and determines the attenuated HIV-2 disease phenotype.

Using genome wide expression analysis we found that HIV-2 stimulation induced a gene expression pattern distinct from HIV-1, characterized by lower expression of type I IFN genes despite similar expression profiles of IFN-stimulated genes (ISG), pattern recognition receptors (PRR) and IFN-regulated viral restriction factors. Plasmacytoid DC (pDC) were identified as the main source of IFN-α following viral exposure in vitro. Examination of type I IFN secretion further revealed significant differences between HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-2 stimulation favoured the development of an antigen-presenting cell (APC) phenotype in pDC, rather than maturation into IFN-α-producing cells, although IFN-I levels were sufficient to enhance the expression of antiviral restriction factors and innate immune mechanisms. Importantly, stimulation with HIV-2 inhibited IFN-α production even in response to the synthetic TLR-9 ligand CpG-A. The preferential induction of an APC phenotype in the absence of high levels of IFN-α may be a critical contributor to the development of efficient T cell responses and to the lower pathogenicity observed during HIV-2 infection.

Materials and Methods

HIV-1 and HIV-2 quantification and normalization

All viruses were quantified and normalized based on RNA content, thus ensuring that the dendritic cells were exposed to the same amount of TLR ligand. Viral RNA was extracted from purified virus and reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix kit (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) with 50ng/μl random hexamers, according to the following thermal profile: 25°C for 10 minutes, 50°C for 50 minutes and 85°C for 5 minutes. cDNA was stored at -20°C until use. Quantitative Real Time PCR was carried out using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN, Manchester, UK), using the following primers (Invitrogen) at 0.5μM: HIV-1 gag forward (5′-3′) GGC TTT CAG CCC AGA AGT AAT ACC C, reverse (5′-3′) TTG CAT GGC TGC TTG ATG TCC CC, HIV-2 gag forward (5′-3′) TGT GGG CGA CCA TCA AGC AGC, reverse (5′-3′) CCG CTG GTA AGG GGC CTG GTA. Reaction plates were incubated as follows: 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds. For quantification purposes a standard curve was run on every plate. Standards were generated from pre-quantified plasmids containing the HIV-1 or HIV-2 amplicon sequence (Geneart, Regensburg, Germany).

For comparison, HIV-1 p24 was also quantified by ELISA (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA, USA). 13 ×109 RNA copies/ml of HIV-1MN propagated in H9 cells corresponded to 668.7 ng/ml p24.

Isolation of cells and in vitro culture

Blood from healthy subjects was obtained from the NHS Blood and Transplant Service in the form of component donation leukocyte cones. PBMC were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphocyte separation medium 1077 (PAA Laboratories, Somerset, UK) and cultured at 2 ×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2mM L-Glutamine, 100U/ml Penicillin and 0.1mg/ml Streptomycin (all reagents sourced from PAA Laboratories). All HIV-1 and HIV-2 isolates were added at 13, 3.9, 1.3 or 0.39 ×109 RNA copies/ml as described in the Results section. Unless otherwise specified, HIV-1 refers to HIV-1MN grown in H9 cells, and HIV-2 refers to HIV-2NIH-Z grown in the HuT78 cell line. CpG-A (ODN2216, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) was used at a concentration of 0.5μM. Cells were harvested after 6 and 12 hours for gene expression analysis and after 9 and 24 hours for analysis of cell surface markers by flow cytometry. Cell culture supernatants were collected at up to seven different time points (3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 and 48 hours) and immediately frozen at -80°C for future analysis of IFN-α and IDO activity.

Plasmacytoid DC were enriched from PBMC using the negative isolation kit (Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Isolation kit II; Miltenyi Biotec, Surrey, UK), according to manufacturer instructions. Enriched pDC were cultured at either 0.5 or 1 ×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2mM L-Glutamine, 100U/ml Penicillin and 0.1mg/ml Streptomycin, in presence of 1ng/ml IL-3. Stimulation was carried out using either 3.25 or 6.5 ×109 RNA copies/ml RNA copies/ml of HIV-1 or HIV-2. This viral concentration was used to match the multiplicity of infection used in PBMC cultures of 2×106 cells/ml. Cells were harvested after 24 hours of culture and analysed using the flow cytometry IFN-α secretion assay as described below.

IFN-α ELISA

IFN-α analysis was performed on frozen cell culture supernatants using the Human IFN-α Multi-Subtype ELISA Kit (PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Kynurenine and tryptophan measurement

Kynurenine (Kyn) and Tryptophan (Trp) were measured in cell culture supernatants by HPLC as previously described (29). The Kyn/Trp ratio was calculated as an estimate of IDO activity.

Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated for 20 mins with combinations of the following antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human CD80 clone 2D10.4 (eBioscence, Hatfield, UK); phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD83 clone HB15e (eBioscience); Peridinin Chlorophyll Protein Complex (PerCP)-CyChrome (Cy)5.5-conjugated anti-human CD86 clone IT2.2 (Biolegend, London, UK); PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD123 clone 6H6 (Biolegend); Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-human CD303 (BDCA2) clone AC144 (Miltenyi Biotec); APC-H7-conjugated anti-human CD14 clone MϕP9 (BD biosciences, Oxford, UK); Brilliant Violet 421-conjugated anti-human CD83 clone HB15e (Biolegend). Cells were acquired on a BD LSR-II using FACSDiva software (BD biosciences), and FlowJo (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA) was used for data analysis.

IFN-α secretion was measured using an IFN-α secretion assay (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, after stimulation in the presence or absence of either HIV-1 or HIV-2, cells were labelled with IFN-α catch antibody (Miltenyi Biotec). In order to allow for the cells to secrete IFN-α, cells were diluted in culture media to a concentration of 1 ×106 cells/ml. Tubes were then placed at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 20 mins, and rotated every 5 mins in order to resuspend settled cells. Cells were subsequently labelled with IFN-α detection antibody conjugated to PE plus a combination of fluorescently conjugated monoclonal antibodies (listed above) for 20mins. Following this, cells were incubated with Fixable Viability Dye (FVD) eFluor® 506 (eBioscience) in order to exclude dead cells from analysis. Cell were acquired on a BD LSR-II using FACSDiva software (BD biosciences), and FlowJo (Treestar) and SPICE (NIAID, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for data analysis.

The median number of events recorded for pDC was 414 (IQR=283-607).

Gene Array

A genome wide array was performed on 3 independent healthy donors. PBMC were isolated and exposed to CpG-A or 13 ×109 RNA copies/ml of either HIV-1MN or HIV-2NIH-Z. Cells were collected after 6 and 12 hours. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini extraction kit (QIAGEN) and subsequently concentrated using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of extracted RNA was determined by measuring absorbance at 260nm, 230nm and 280nm wavelengths (NanoDrop 1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), and the quality was checked using the Agilent Bioanalyzer, only samples with a RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of 7.5 were used. Ambion WT Expression kit was used to prepare the cDNA, which was then labeled using the Affymetrix GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling kit (Affymetrix, High Wycombe, UK). Samples were run on the Human Gene 1.0ST version 2 arrays (Affymetrix), which contains probe sets for over 40,000 transcripts. Partek Genomics 6.6 (Partek Inc., Saint Louis, MO, USA) was used for data analysis. Individual CEL files were corrected using RMA background correction. Normalization was performed using quantiles and median polish used for probe set summarization. Results were expressed as log2. Data sets from different time points were treated separately. Gene microarray data are available on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE58994 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE58994).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis for the gene array data was performed with Partek genomics using a 2-way ANOVA, cross comparing HIV-1, HIV-2 and CpG-A to media alone, with donor as a random variable. Only genes which had a two-fold change in expression relative to media and were considered statistically significant (Benjamini & Hochberg corrected p-value <0.05) were selected for further analysis. The Partek Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment function was used to identify groups of genes based on their biological function. Gene enrichment was performed on 3 separate lists of genes; those differentially regulated by i) both HIV-1 & HIV-2, ii) HIV-1, and not by HIV-2, iii) HIV-2, and not by HIV-1.

Spearman rank tests were performed for correlation analysis using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical analyses for all other data were performed using SPSS Version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Different culture conditions were compared using a non-parametric Friedman test. Pairwise comparisons were subjected to Dunn’s correction. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

HIV-1 and HIV-2 differentially regulate type I IFN genes but induce similar innate antiviral responses

HIV-1MN and HIV-2NIH-Z were normalized based on viral RNA (13 ×109 RNA copies/ml, final concentration, measured by real time PCR) and used as stimuli for cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy uninfected donors. Viral nucleic acids are pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) which potently stimulate innate immunity via PRR. Thus, normalization based on nucleic acid content guarantees that the cells were exposed to the same amount of PAMP from the two viruses.

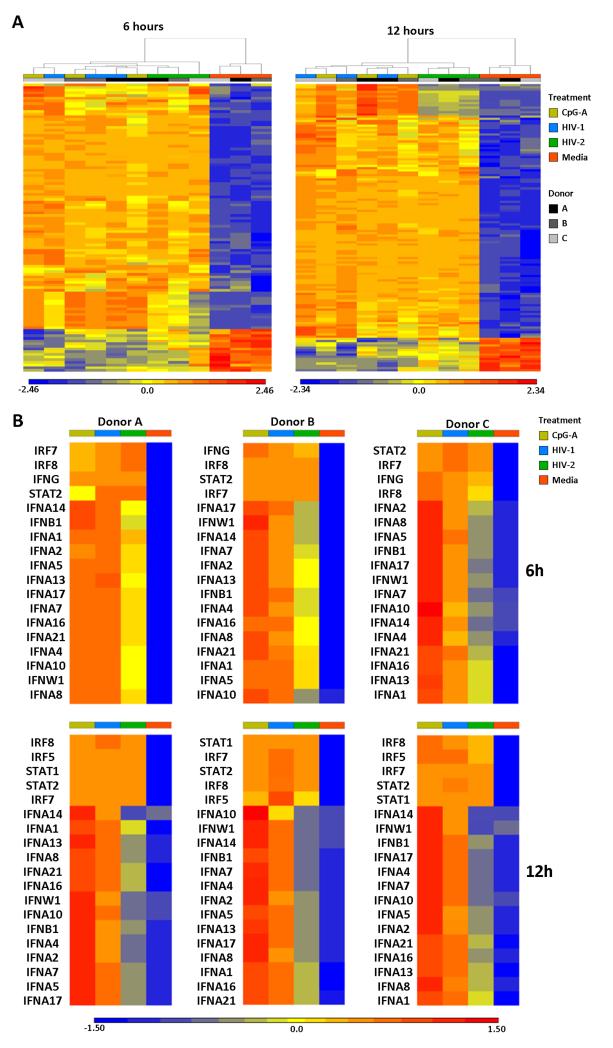

Whole gene array was performed on PBMC from 3 uninfected donors cultured with HIV-1MN, HIV-2NIH-Z (from here on referred to as HIV-1 and HIV-2), CpG-A oligodeoxynucleotide or cell culture media alone for 6 or 12 hours. Differential regulation of specific subsets of genes by HIV-2 compared to HIV-1 or CpG-A was observed in all donors and highlighted by principal component analysis (PCA) (Supplemental Fig. 1A), ANOVA-based analysis of differentially expressed genes (Supplemental Fig. 1B) and unbiased hierarchical clustering of genes shortlisted by ontology enrichment (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Gene expression profile of PBMC stimulated with HIV-1, HIV-2 or CpG-A.

(A) Heat map of genes showing significant differences in expression (at least 2-fold change and P<0.05 as per ANOVA) and belonging to enriched gene ontology categories in PBMC from three independent donors stimulated with HIV-1 (blue), HIV-2 (green), CpG-A (yellow) or media alone (orange) for 6 (left heat map) and 12 hours (right heat map). Each column represents the response from a single donor in each condition; colour and grayscale bars on top of each heat map indicate culture conditions and donor code (A, B or C), according to the legend on the right; columns were ordered by unbiased hierarchical clustering. (B) Heat maps of IFN-I, IFN-II, IFN signalling genes in PBMC stimulated with HIV-1 (blue), HIV-2 (green), CpG-A (yellow) or media alone (orange) for 6 (top panels) and 12 hours (bottom panels). Each heat map represents responses in one individual donor. In both (A) and (B), gene expression levels are indicated by colour transitions from blue (lowest expression) to red (highest expression) according to the legend displayed below each graph.

Classification of genes into sub groups according to AmiGO analysis (Version 1.8, GO database release 2013-11-09) and available literature indicated the most substantial differences were observed in IFN-I gene expression, which was higher in PBMC stimulated with HIV-1 and CpG-A compared to HIV-2 (Fig. 1B). This pattern was observed across all 3 donors at both 6 and 12 hours. Interestingly, all stimuli induced similar increases in the expression of genes involved in IFN signaling at 6 hours (IRF7, IRF8 and STAT2) and 12 hours (IRF7, IRF8, STAT2, STAT1 and IRF5) (Fig. 1B), as well as ISG (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Furthermore, a similar up-regulation of viral restriction factors (Supplemental Fig. 1D) and apoptosis-related genes (data not shown) was observed with HIV-1, HIV-2 and CpG-A compared to media at both time points. Expression of eleven PRR-associated genes (including TLR3, TLR7 and NOD1) was equally increased in response to all three stimuli at 6 hours (data not shown). Similar up-regulation of 13 PRR-associated genes (including TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and NOD1) was observed after 12 hours, whereas the expression of CLEC4A, CLEC5A and NLRC4 was reduced in HIV-1- and CpG-A-stimulated cells, but only marginally in HIV-2-stimulated cells compared to media after 12 hours (data not shown).

A subset of genes associated with the activation and regulation of the adaptive immune response were down-regulated after 6 hours in response to all stimuli, but their expression remained higher in HIV-2-stimulated cells compared to either HIV-1 or CpG-A (Supplemental Fig. 1E). The expression of genes associated with antigen processing and presentation was equally increased in response to all stimuli after 12 hours (Supplemental Fig. 1E). Similar expression profiles were observed for cytokine and chemokine genes in HIV-1-, HIV-2- and CpG-A-stimulated samples, with the exception of reduced expression of a select number of chemokine genes after 12 hours stimulation with HIV-1, an effect which was less pronounced in response to HIV-2 exposure (data not shown).

Genome wide expression data collectively demonstrates that acute responses to HIV-1 and HIV-2 exposure differ primarily in IFN-I gene activation, despite eliciting robust innate responses as measured by ISG and viral restriction factors.

HIV-2 induces delayed and reduced IFN-α responses compared to HIV-1

We tested the kinetics and dose-response of IFN-α production in vitro. PBMC were cultured in the presence or absence of varying concentrations of either HIV-1 or HIV-2. Cell culture supernatants were collected at multiple time points between 3 and 48 hours. Figures 2A-D show results obtained with different concentrations of virus. In all cases there was no measurable IFN-α at 3 (data not shown) and 6 hours. Overall, IFN-α secretion was higher in response to HIV-1 than HIV-2 in all conditions tested. Specifically, HIV-1 induced significantly greater IFN-α secretion compared to media alone at all time points between 9 and 48 hours. In contrast, HIV-2 induced significantly higher IFN-α production compared to media after 24 hours. Increased sample size at 9 and 24 hours also revealed that HIV-1 was significantly more potent than HIV-2 in stimulating IFN-α production. Similar results were found across all concentrations tested. When IFN-α production at 24 hours was analyzed, we observed that stimulation with both viruses achieved the maximum response within the range of concentrations used (Supplemental Fig. 2A), and confirmed that the difference between HIV-1 and HIV-2 is not resolved by simply increasing HIV-2 concentrations.

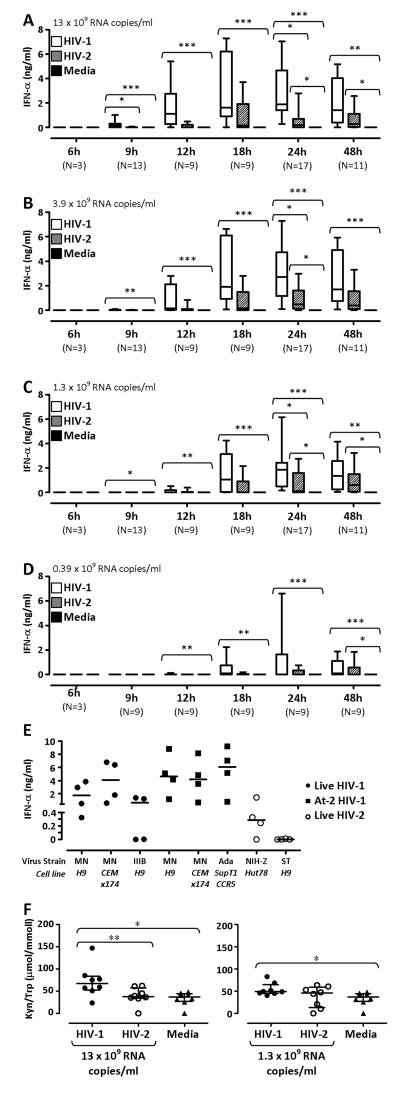

Figure 2. IFN-α secretion in response to HIV-1 and HIV-2 stimulation.

(A), (B), (C) and (D) show the concentration of IFN-α detected by ELISA in PBMC culture supernatants after stimulation for 6 to 48 hours with varying concentrations of virus, as indicated in the top left of each graph. Responses to HIV-1 are denoted by open boxes, HIV-2 by diagonal pattern filled boxes, and responses to media alone are shown by solid boxes. Horizontal lines within boxes represent median values, boxes show interquartile ranges (IQR) and lines extent to 90th and 10th percentiles. (E) Shows IFN-α detected by ELISA in PBMC culture supernatants after stimulation for 24 hours with HIV-1MN/H9, HIV-1MN/CEMx174, HIV-1IIIB/H9, aldrithiol (At)-2 treated HIV-1MN/H9, At-2 HIV-1MN/CEMx174, At-2 HIV-1Ada/SupT1-CCR5, HIV-2NIH-Z/Hut78 or HIV-2ST/CEMx174. Solid circles indicate responses against replication-competent HIV-1 isolates, solid squares represent At-2-treated isolates and open circles HIV-2 isolates. Horizontal lines represent median values. (F) shows Kyn/Trp ratios in PBMC culture supernatants after stimulation for 24 hours with HIV-1 (solid circles) or HIV-2 (open circles), at 13 × 109 RNA copies/ml (left panel) and 1.3 × 109 RNA copies/ml (right panel), or media alone (triangles). Horizontal lines indicate median values and vertical lines show the IQR. In all graphs, responses to HIV-1, HIV-2 and media within individual time points and virus concentrations were compared using a Friedman test with a Dunn’s post test for multiple analyses. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001

We also tested the ability of isolates other than HIV-1MN and HIV-2NIH-Z to induce IFN-α secretion. Although differences were observed between viral strains, overall, HIV-1MN, HIV-1IIIB and HIV-1Ada induced the secretion of higher levels of IFN-α compared to HIV-2NIH-Z, and HIV-2ST (Fig. 2E). Similar concentrations of IFN-α were detected following stimulation with replication competent CXCR4-tropic HIV-1MN and reverse transcription deficient aldrithiol-2 (At-2)-treated HIV-1MN (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, IFN-α levels remained unchanged when PBMC were stimulated with either HIV-1MN or HIV-2NIH-Z in the presence of the reverse transcriptase inhibitor AZT (Supplemental Fig. 2B), indicating that viral replication did not contribute to enhanced IFN-α responses. Similar IFN-α production was also observed using CCR5-tropic At-2 HIV-1Ada and HIV-1MN grown in either H9 cells or CEMx174 cells (Fig. 2E), suggesting that co-receptor usage and the cell line used for virus propagation also did not influence IFN-α secretion in response to HIV-1.

HIV-1 also proved to be a more potent inducer of the activity of the immunosuppressive enzyme IDO, measured as the ratio between the concentrations of tryptophan (Trp) and its catabolite kynurenine (Kyn) in culture supernatants. No measurable Trp catabolism was observed after 9 hours of stimulation with either HIV-1 or HIV-2 (data not shown). After 24 hours HIV-1, but not HIV-2, significantly stimulated IDO activity compared to unstimulated cells when used at both 13 and 1.3 × 109 copies/ml (Fig. 2F). In addition, using 13 ×109 RNA copies/ml of virus, HIV-1 induced a significantly higher Kyn/Trp ratio, indicating increased IDO activity, compared to HIV-2-stimulated PBMC (Fig. 2F).

We investigated whether the differential effect of HIV-1 and HIV-2 on PBMC stimulation extended to the production of other inflammatory cytokines. Production of IL-8, TNF-α and IL-1β was not significantly changed in response to either HIV-1 or HIV-2 (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Increased IL-6 production was observed in response to both viruses at 24 hours; and significantly exceeded control in the case of HIV-2 stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 2C).

HIV-1 and HIV-2 induce comparable levels of pDC activation

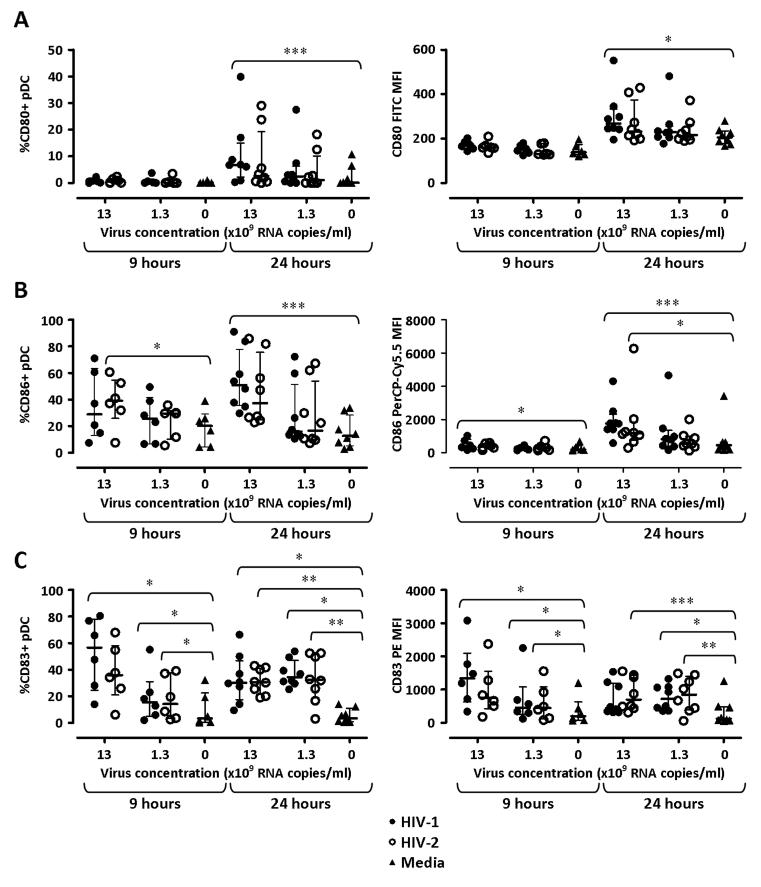

Previous data indicate that pDC are the main producers of IFN-α and IDO among HIV-stimulated PBMC in vitro (6, 30, 31). Thus, we investigated the induction of co-stimulatory molecules, CD80 and CD86, as well as the activation marker CD83 on pDC following PBMC stimulation with HIV-1 or HIV-2 (gating strategy shown in Supplemental Fig. 3A-D). CD80 expression was negligible after 9 hours under all culture conditions (Fig. 3A). When used at 13 ×109 RNA copies/ml, HIV-1 induced a statistically significant up-regulation of CD80 expression on pDC after 24 hours compared to unstimulated PBMC (Fig.3A). HIV-2 stimulation induced CD86 expression on a higher frequency of pDC compared to media alone after 9 hours, whereas HIV-1-induced CD86 expression reached statistical significance after 24 hours (Fig. 3B). CD83 expression was minimal in cultures with media alone after 9 and 24 hours (Fig. 3C). Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 increased the frequency of CD83-expressing pDC compared to unstimulated PBMC at both 9 and 24 hours. Analysis of CD80, CD86 and CD83 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) showed profiles similar to those observed for the frequencies of marker-expressing cells, and confirmed that the enhanced induction of IFN-α by HIV-1 compared to HIV-2 is not mirrored by differences in phenotypic pDC activation (Fig. 3A-C). Similar profiles, characterized by milder changes in the expression of all three markers, were observed when lower concentrations (1.3 ×109 RNA copies/ml) of HIV- and HIV-2 were used (Fig. 3A-C).

Figure 3. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules and CD83 on pDC after HIV-1 and HIV-2 stimulation.

Expression of CD80 (A), CD86 (B) and CD83 (C) on pDC was analysed by flow cytometry after 9 and 24 hours stimulation with 13 ×109 or 1.3 ×109 viral RNA copies/ml of either HIV-1 (solid circles) or HIV-2 (open circles), or with cell culture media alone (triangles). Left panels show the frequencies of pDC expressing the marker of interest, and right panels show the MFI for each marker. Each dot represents one individual donor. Horizontal bars represent median values and vertical lines extend to the IQR. Responses to HIV-1, HIV-2 and media alone within individual time points and virus concentrations were compared using a Friedman test with a Dunn’s post test for multiple analyses. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001

Because IFN-I promotes the activation and maturation of other APC, we also tested the regulation of CD80 and CD86 on myeloid dendritic cells (mDC) and monocytes, the two other main APC subtypes present in PBMC (gating strategy shown in Supplemental Fig. 3A-D). CD80 expression by mDC was negligible in all conditions tested, whereas the frequency of CD86+ mDC approached 100% in all conditions (Supplemental Fig. 4A & 4B). CD86 MFI was mildly increased in mDC following PBMC stimulation with HIV-1 or HIV-2, but no substantial differences were observed between the two viruses (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Minor changes were observed in the frequencies of CD80+ monocytes in response to both viruses, which tested significant only in response to HIV-1, whereas CD80 MFI, as well as CD86 MFI and the frequency of CD86+ monocytes, were enhanced by both viruses at comparable levels (Supplemental Fig. 4C & 4D).

Reduced IFN-α production in response to HIV-2 is associated with the development of an APC phenotype by pDC

Functionally distinct mature pDC subsets develop after stimulation with different synthetic ligands, either promoting the development of IFN-I producing cells or inducing the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (32, 33). We therefore investigated the expression of CD86 and CD83 on pDC in conjunction with active secretion of IFN-α following stimulation with either HIV-1 or HIV-2 (gating strategy shown in Supplemental Fig. 3E & 3F).

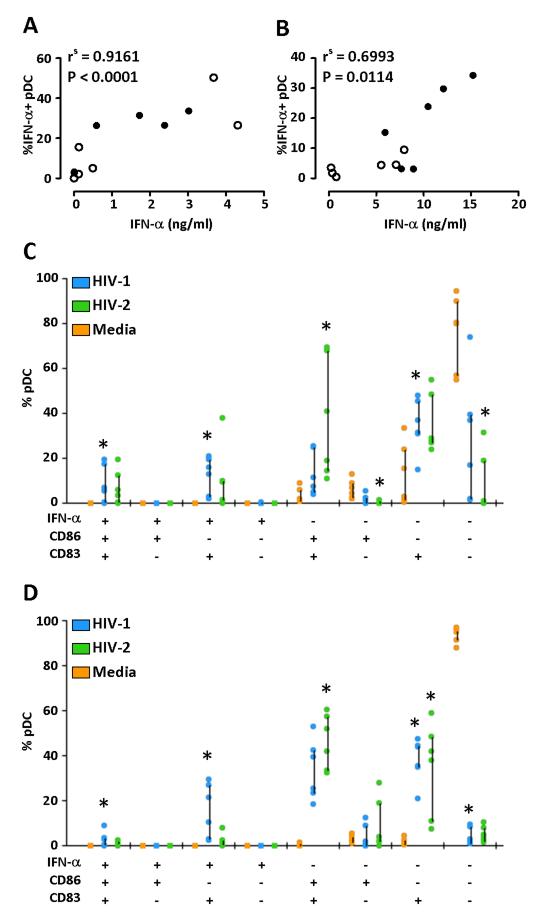

We observed a strong positive correlation between the frequency of IFN-α-secreting pDC and IFN-α levels in supernatants in different culture conditions at both 9 and 24 hours (Fig. 4A & 4B), confirming that pDC are the main cell type responsible for IFN-α production in this experimental setting.

Figure 4. Differentiation of pDC into IFN-I-producing or phenotypic antigen-presenting cells following HIV-1 or HIV-2 stimulation.

(A) and (B) show the correlation between the frequency of IFN-α secreting pDC detected by flow cytometry and the concentration of IFN-α secreted in cell culture supernatants measured by ELISA after 9 (A) and 24 hours (B). Solid circles show responses to HIV-1 and open circles denote responses to HIV-2. Correlation was performed using a non-parametric spearman rank test. (C) and (D) show SPICE analysis of IFN-α secretion, CD83 and CD86 expression at 9 (C) and 24 hours (D). Differences in the frequencies of pDC expressing different combinations of CD83, CD86 and secreted IFN-α in response to media alone (orange), HIV-1 (blue) and HIV-2 (green) were analysed using a Friedman test with a Dunn’s post test for multiple analyses. *p≤0.05.

The frequency of triple positive pDC (CD83+, CD86+, IFN-α+) was low in all conditions at both 9 and 24 hours (Fig. 4C and 4D, respectively), confirming previous observations that pDC maturation into IFN-I-producing or antigen-presenting cells are mutually exclusive. In addition, both IFN-α secretion and CD86 expression by pDC were associated with increased CD83 expression, suggesting that upregulation of the activation marker CD83 occurs independent of the pDC differentiation pathway.

HIV-1 stimulation induced a significantly higher frequency of IFN-α+/CD86−/CD83+ pDC compared to unstimulated cells (Fig. 4C and 4D). Conversely, HIV-2 induced a significantly greater proportion of IFN-α−/CD86+/CD83+ pDC compared to unstimulated cells.

These data suggest that HIV-1 and HIV-2 stimulate pDC differentiation along different pathways, namely IFN-I production and APC maturation, respectively.

A similar pattern, in which HIV-2 induced a higher frequency of CD86+ pDC, whereas HIV-1 promoted more potent IFN-α secretion, was observed after 24 hours culture of enriched pDC (isolated by negative selection with magnetic beads and cultured in presence of the survival factor IL-3; purity >90%), albeit the frequency of activated pDC appeared to be lower than that observed with unseparated PBMC (Supplemental Fig. 3G). These data suggest that the presence of cells other than pDC may not be necessary to drive differential maturation, but may be required to achieve optimal pDC stimulation.

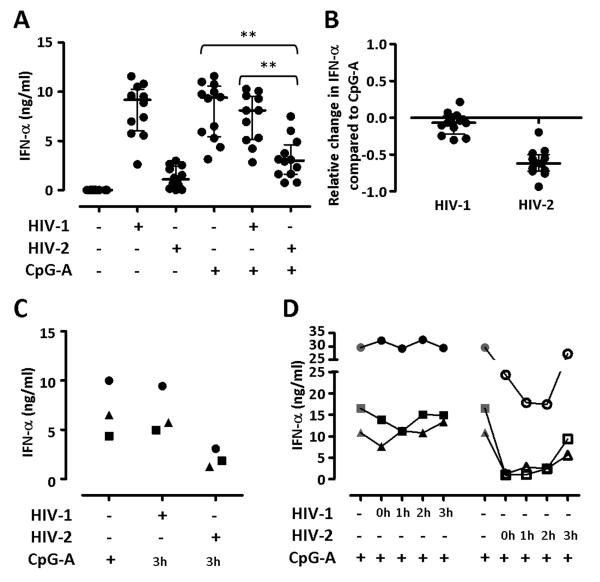

HIV-2-induced pDC maturation into phenotypic APC prevents IFN-α production in response to the synthetic TLR-9 ligand CpG-A

We investigated whether HIV-2 stimulation affected the ability of pDC to produce IFN-α in response to the synthetic TLR-9 ligand CpG-A. PBMC were stimulated with 13 × 109 RNA copies/ml of either HIV-1 or HIV-2 in the presence or absence of CpG-A. Supernatants were collected after 24 hours and IFN-α concentration determined by ELISA. As expected CpG-A alone was a potent stimulus for IFN-α production, which remained unaltered in the presence of HIV-1 (Fig. 5A & 5B). However, when HIV-2 and CpG-A were added together there was a significant reduction in secreted IFN-α compared to CpG-A alone, highlighting the dominant effect of HIV-2 over the IFN-I inducing stimulus. A similar inhibition was observed when HIV-2 was added to PBMC 3 hours before (Fig. 5C) or up to 2 hours after (Fig. 5D) CpG-A stimulation. Conversely, the inhibitory effect of HIV-2 on CpG-A-induced IFN-α production was dramatically reduced when the virus was added 3 hours after CpG-A (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. HIV-2 suppresses IFN-α secretion in response to CpG-A.

(A) Shows IFN-α production measured by ELISA in supernatants from PBMC cultured for 24 hours with CpG-A in the presence or absence of 13 ×109 viral RNA copies/ml HIV-1 or HIV-2. CpG-A alone and the addition of either HIV-1 or HIV-2 were compared using a Friedman test with a Dunn’s post test for multiple analyses; *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001. (B) Shows the relative change in IFN-α secretion after the addition of HIV-1 or HIV-2 compared to CpG-A alone, calculated as ((HIV+CpG)-CpG)/CpG). In both (A) and (B), each dot represents one individual donor. Horizontal bars represent median values and vertical lines extend to the IQR. (C) Shows IFN-α production measured by ELISA in supernatants from PBMC pre-incubated with 13 ×109 viral RNA copies/ml HIV-1 or HIV-2 for three hours prior to the addition of CpG-A, and then cultured for 24 hours. Each symbol represents an independent donor. (D) Shows IFN-α production measured by ELISA in supernatants from PBMC cultured for 24 hours with CpG-A in presence or absence of 13 ×109 viral RNA copies/ml HIV-1 or HIV-2 added at the same time of CpG-A stimulation (0h) or one, two or three hours after stimulation (1h, 2h and 3h, respectively). Each symbol represents an independent donor.

Discussion

HIV-2 shares many of the biological features of HIV-1, but is less pathogenic, causing a slow progressing disease characterized by low plasma viral load and reduced levels of immune activation (15, 27, 34-36). One leading hypothesis to explain the different disease outcome is that more efficient T cell responses are induced and maintained during HIV-2 infection, and allow prolonged immune-mediated control of viral replication (12). Thus, the course of disease in HIV-2 infected patients is similar to that observed in HIV-1 LTNP, in that adaptive immunity controls viral activity. The reasons why HIV-2 elicits a more efficient antiviral adaptive response compared to HIV-1 are still obscure, but immunologic and inflammatory events which occur early during viral exposure are likely to influence the quality and potency of the adaptive response.

We examined the effects of acute exposure of uninfected PBMC to HIV-1 and HIV-2. We found that HIV-2 stimulation induced a gene expression profile distinct from HIV-1, characterized by reduced expression of type I IFN genes, which was due to preferential induction of an APC phenotype in pDC rather than maturation into IFN-producing cells. Most important, HIV-2-induced pDC maturation into phenotypically-defined APC was dominant over type I IFN production even when cells were stimulated with CpG-A. Although additional studies investigating the APC function of HIV-1- and HIV-2-stimulated pDC are required, our data suggest that the balance between pDC maturation into IFN-producing or antigen-presenting cells is a critical factor differentiating the early response against the two viruses. Based on these data, we hypothesize that the pathway of pDC differentiation during early viral exposure is an important determinant of the outcome of HIV infection.

Differential pDC maturation in response to HIV-1 and HIV-2 was also observed in enriched pDC cultures, but the levels of pDC activation appeared lower compared to that observed with unseparated PBMC. These data suggest that the presence of other cells may be required to facilitate full pDC activation, either by secretion of other immunotropic factors, or by facilitating viral interaction with pDC. One caveat is that cultures of enriched pDC require the addition of exogenous IL-3 as a survival factor, which has been shown to modify pDC maturation by promoting the development of APC which stimulate Th2 CD4 T cell differentiation (37). Thus, in vitro culture of enriched pDC supplemented with IL-3 may not represent a biologically relevant experimental setting, and results obtained in this system should be treated with caution.

Interestingly, Cavaleiro and colleagues reported that similar reductions of pDC numbers are observed in HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected patients with similar levels of CD4 depletion, despite significant differences in plasma viral load (17). The decrease in circulating pDC may be secondary to comparable degrees of pDC activation and relocation to lymphoid tissues during HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection. This is consistent with our data indicating that both viruses activate pDC to a similar degree, as measured by CD83 expression, but differentially modulate the function of activated pDC.

We have previously shown that removing the ability of HIV-1 to stimulate IFN-I secretion and IDO, while preserving the capacity to induce high expression of co-stimulatory molecules on pDC, resulted in a greater ability to stimulate secondary HIV-1-specific memory T cells (5). This is consistent with the findings by O’Brien and colleagues showing that CpG-B stimulated pDC, which activated co-stimulatory molecule expression over IFN-α secretion, elicited more efficient T cell proliferation than pDC stimulated with CpG-A or HIV-1 (32). Importantly, the activation of mDC and monocytes, measured as up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules, was comparable between HIV-1 and HIV-2, suggesting that efficient stimulation of other APC occurs even in conditions of low IFN-α production upon exposure to HIV-2.

Patients infected with HIV-2 show enhanced HIV-specific T cell responses compared to HIV-1+ patients. A study comparing HIV-2+ patients with undetectable and high viral loads showed that the ability to control viral replication correlated with HIV-2 Gag-specific CD8+ T cell responses (27). Consistent with this view, we observed that the levels of IDO activity induced by HIV-2 were significantly lower compared to HIV-1. IDO is an immunoregulatory enzyme which suppresses T cell proliferation and drives the differentiation of regulatory T cells (38, 39). Increased IDO activity has been reported in HIV-1 infected patients and is associated with disease progression (6, 40-42), likely contributing to viral persistence by suppressing antiviral T cell responses. The gene array data we report here are consistent with the hypothesis that the adaptive immune response is more efficiently induced by HIV-2 than HIV-1. Thus, genes involved in B cell signaling (CD79B, GAPT), T cell activation (CD27, LAT) and T cell migration (ITGB7, AMICA1) were expressed at higher levels in PBMC stimulated with HIV-2 compared to HIV-1.

Plasmacytoid DC produce 1000-fold more IFN-I than any other cell type in the blood, and are key mediators of the innate immune response, by both limiting viral replication and enhancing the adaptive arm of the immune response (43). Dysregulation of the IFN-I system has been suggested by us and others to contribute to different aspects of HIV-1 immunopathogenesis, including induction of CD4 T cell apoptosis, suppression of CD8 T cell responses, generalized lymphadenopathy and promotion of an activated phenotype in T cells (3, 44-47). However, the contribution of different cell types to the sustained and prolonged production of IFN-I may change during the transition between acute and chronic infection. Recent evidence suggests that pDC may be the main source of IFN-I during acute infection, and they may be replaced by mDC and macrophages during the chronic phase (48). Macrophages and mDC, different from pDC, do not produce IFN-I following stimulation of endosomal TLR, but secrete IFN-I follwing stimulation of cytoplasmic PRR triggered during the early steps of the viral life cycle (49). In addition, Harman and colleagues demonstrated that productive infection of monocyte-derived DC by HIV-1 inhibits IFN-I secretion via IRF1 induction, and that this effect is characteristics of cells expressing newly synthesized viral proteins (50). Our data showing that similar levels of IFN-α are induced by HIV-1 and HIV-2 independent of the replicative capacity of the viruses argue against the possibility that a similar mechanism may occur in pDC. Thus, pDC may be critical in influencing the innate immune response and the development of adaptive immunity following viral exposure during primary HIV-1 infection, but may play a secondary role in IFN-I-mediated pathogenesis during the chronic phase.

Microarray analysis showed different gene expression profiles in PBMC exposed to HIV-1 and HIV-2 respectively. In particular, we found that HIV-2 induced lower expression of IFN-I genes compared to both HIV-1 and CpG-A, and expression of some IFN-I genes following HIV-2 stimulation were more similar to unstimulated than HIV-1-stimulated cells. Measurement of IFN-α concentrations in cell culture supernatants in vitro confirmed these results at a translational level across a wider range of virus concentrations and throughout a 48 hour kinetic. The differences in IFN-α secretion extended to other HIV-1 and HIV-2 isolates, irrespective of HIV-1 co-receptor usage and the cell line used for viral propagation, and were not a result of different replication rates. We normalized virus concentrations based on RNA, ensuring that the difference in IFN-α production is not due to differences in the amount of TLR ligand. In addition, even when PBMC were stimulated with HIV-2 at concentrations up to 10 fold higher than that used for HIV-1, the difference in IFN-α production was preserved. These data demonstrate that the discrepancy between early immune responses against HIV-1 and HIV-2 are due to qualitative differences in virus-host interactions rather than caused by different amounts of viral stimuli.

Despite the striking difference in IFN-α stimulation, HIV-2 induced a robust innate immune response, similar to HIV-1. In particular, the expression profiles of PRR-associated and IFN-regulated viral restriction factor genes were similar in response to the two viruses. The up-regulation of IFN-stimulated viral restriction factors (APOBEC3A, TRIM family members, SAMHD1, Tetherin/BST2) is of particular biological interest, because it suggests that molecular mechanisms of viral inhibition may be equally induced by HIV-1 and HIV-2 during the early stages of viral exposure.

The production of other cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8 and IL-6, was similar between HIV-1 and HIV-2, suggesting that the difference in inflammatory responses against the two viruses was limited to IFN-α. The strong correlation between the frequency of IFN-α-secreting pDC and the concentration of IFN-α detected in cell culture supernatants underscores the role of pDC in driving IFN-α responses during acute viral exposure.

CD83 is rapidly up-regulated by pDC upon activation via TLR. We observed that while secretion of IFN-α was always associated with CD83 expression, there was a high frequency of activated pDC which expressed only CD83 after viral stimulation. Three non-mutually exclusive explanations may be considered for this phenomenon: 1) only a fraction of IFN-α-secreting cells can be detected within the 20 minute window when cells are incubated with the detection antibody in our assay; 2) CD83 single positive pDC may represent activated cells which are not yet committed to become either IFN-producing or APC; or 3) CD83+ IFN-α-negative CD86-negative cells may represent a population of activated pDC exerting functions other than IFN-α secretion, for example production of other inflammatory cytokines.

Our data indicate that HIV-2 promotes pDC differentiation along a different pathway compared to HIV-1, favouring co-stimulatory molecule expression over IFN-I. Very few CD86+ IFN-α+ pDC were detected, suggesting either that 1) the subpopulation of CD83+CD86+ cells secreted IFN-α only during the early phases of exposure, before the assessment made at 9 and 24 hours; or 2) IFN-I production and APC maturation are mutually exclusive. The latter hypothesis is supported by studies comparing the effect of CpG-A and CpG-B stimulation on pDC, in which alternative differentiation is observed (32, 33). A growing body of evidence suggests that different intracellular trafficking of TLR agonists within pDC results in alternative maturation pathways and different activated phenotypes. Similar to CpG-A, HIV-1 has been shown to traffic to the early endosome where it stimulates persistent IFN-α secretion via IRF7 induction, whereby CpG-B traffics to the lysosome resulting in preferential activation of the NF-κB pathway and up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules, yet weakly stimulating IFN-I secretion (32). In our experiments, we normalized HIV-1 and HIV-2 based on RNA copies/ml, thus ensuring that the same amount of TLR agonist was added to the cultures. Thus, the differences in pDC activation may be a consequence of different uptake, intracellular trafficking or accessibility of viral RNA for TLR stimulation due to different dynamics of uncoating between the two viruses.

HIV-2 infection is not only less pathogenic than HIV-1, but may also be beneficial in the context of co-infection. HIV-1-infected patients with pre-existing HIV-2 infection display a slower disease progression phenotype, characterized by higher CD4+ T cell counts (51). A study by Jaehn and colleagues reported that pDC simultaneously exposed to CpG-A and CpG-B respond with an activated phenotype more similar to that induced by CpG-B alone (33). Consistent with this report, we found that when PBMC were stimulated with HIV-2 and CpG-A together, IFN-α secretion was significantly reduced compared to CpG-A alone. Thus, it is possible that in conditions of pre-existing HIV-2 infection, HIV-1 fails to induce an inflammatory phenotype dominated by IFN-α, alleviating the immune suppression and resulting in slower disease progression. Interestingly, HIV-2 exerted an inhibitory effect on IFN-α secretion only when added within two hours of CpG-A-stimulation, suggesting a time-limited window of opportunity to condition the system and suppress IFN-α responses. Further studies are required to identify which steps of virus-cell interaction are necessary for HIV-2 to prevent pDC maturation into IFN-I-producing cells, and to determine whether similar events occur in vivo in HIV-2/HIV-1 co-infected patients.

Our data demonstrate that HIV types which cause different disease phenotypes in vivo can be characterized by their effect on pDC maturation in vitro. The conditioning of pDC during the acute stages of infection, depending on whether the response is dominated by IFN-α or an APC phenotype, may be a critical determinant of disease outcome. We propose that the pDC differentiation profile during the early phases of infection is critical in shaping the immune response against HIV and contributes to the differences in pathogenicity between HIV-1 and HIV-2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (award n. 085164/Z/08/Z).

Footnotes

We have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Picker LJ, Watkins DI. HIV pathogenesis: The first cut is the deepest. Nature Immunology. 2005;6:430–432. doi: 10.1038/ni0505-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabado RL, O’Brien M, Subedi A, Qin L, Hu N, Taylor E, Dibben O, Stacey A, Fellay J, Shianna KV, Siegal F, Shodell M, Shah K, Larsson M, Lifson J, Nadas A, Marmor M, Hutt R, Margolis D, Garmon D, Markowitz M, Valentine F, Borrow P, Bhardwaj N. Evidence of dysregulation of dendritic cells in primary HIV infection. Blood. 2010;116:3839–3852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boasso A, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Shearer GM. HIV-induced type I interferon and tryptophan catabolism drive T cell dysfunction despite phenotypic activation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boasso A, Hardy AW, Landay AL, Martinson JL, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Clerici M, Shearer GM. PDL-1 upregulation on monocytes and T cells by HIV via type I interferon: Restricted expression of type I interferon receptor by CCR5-expressing leukocytes. Clin Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boasso A, Royle CM, Doumazos S, Aquino VN, Biasin M, Piacentini L, Tavano B, Fuchs D, Mazzotta F, Lo Caputo S, Shearer GM, Clerici M, Graham DR. Overactivation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibits antiviral T-cell responses: a model for HIV immunopathogenesis. Blood. 2011;118:5152–5162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boasso A, Herbeuval JP, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Fuchs D, Shearer GM. HIV inhibits CD4+ T-cell proliferation by inducing indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2007;109:3351–3359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le T, Wright EJ, Smith DM, He W, Catano G, Okulicz JF, Young JA, Clark RA, Richman DD, Little SJ, Ahuja SK. Enhanced CD4+ T-cell recovery with earlier HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:218–230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidler S, Porter K, Ewings F, Frater J, Ramjee G, Cooper D, Rees H, Fisher M, Schechter M, Kaleebu P, Tambussi G, Kinloch S, Miro JM, Kelleher A, McClure M, Kaye S, Gabriel M, Phillips R, Weber J, Babiker A. Short-course antiretroviral therapy in primary HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:207–217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saez-Cirion A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Girault I, Lecuroux C, Potard V, Versmisse P, Melard A, Prazuck T, Descours B, Guergnon J, Viard JP, Boufassa F, Lambotte O, Goujard C, Meyer L, Costagliola D, Venet A, Pancino G, Autran B, Rouzioux C. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain V, Hartogensis W, Bacchetti P, Hunt PW, Hatano H, Sinclair E, Epling L, Lee TH, Busch MP, McCune JM, Pilcher CD, Hecht FM, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy initiated within 6 months of HIV infection is associated with lower T-cell activation and smaller HIV reservoir size. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1202–1211. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berrey MM, Schacker T, Collier AC, Shea T, Brodie SJ, Mayers D, Coombs R, Krieger J, Chun TW, Fauci A, Self SG, Corey L. Treatment of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection with potent antiretroviral therapy reduces frequency of rapid progression to AIDS. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1466–1475. doi: 10.1086/320189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyamweya S, Hegedus A, Jaye A, Rowland-Jones S, Flanagan KL, Macallan DC. Comparing HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection: Lessons for viral immunopathogenesis. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23:221–240. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guyader M, Emerman M, Sonigo P, Clavel F, Montagnier L, Alizon M. Genome organization and transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Nature. 1987;326:662–669. doi: 10.1038/326662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson S, Norrgren H, da Silva Z, Biague A, Bamba S, Kwok S, Christopherson C, Biberfeld G, Albert J. Plasma viral load in HIV-1 and HIV-2 singly and dually infected individuals in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa - Significantly, lower plasma virus set point in HIV-2 infection than in HIV-1 infection. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3286–3293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marlink R, Kanki P, Thior I, Travers K, Eisen G, Siby T, Traore I, Hsieh CC, Dia MC, Gueye E, Hellinger J, Gueyendiaye A, Sankale JL, Ndoye I, Mboup S, Essex M. Reduced Rate of Disease Development after Hiv-2 Infection as Compared to Hiv-1. Science. 1994;265:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.7915856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sousa AE, Carneiro J, Meier-Schellersheim M, Grossman Z, Victorino RM. CD4 T cell depletion is linked directly to immune activation in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and HIV-2 but only indirectly to the viral load. J Immunol. 2002;169:3400–3406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavaleiro R, Baptista AP, Soares RS, Tendeiro R, Foxall RB, Gomes P, Victorino RM, Sousa AE. Major depletion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in HIV-2 infection, an attenuated form of HIV disease. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000667. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavaleiro R, Tendeiro R, Foxall RB, Soares RS, Baptista AP, Gomes P, Valadas E, Victorino RM, Sousa AE. Monocyte and myeloid dendritic cell activation occurs throughout HIV type 2 infection, an attenuated form of HIV disease. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1730–1742. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Steele E, Awasana AA, Corrah T, Sabally S, van der Sande M, Jaye A, Togun T, Sarge-Njie R, McConkey SJ, Whittle H, van der Loeff MFS. Is HIV-2-induced AIDS different from HIV-1-associated AIDS? Data from a West African clinic. Aids. 2007;21:317–324. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011d7ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popper SJ, Sarr AD, Gueye-Ndiaye A, Mboup S, Essex ME, Kanki PJ. Low plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 2 viral load is independent of proviral load: low virus production in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:1554–1557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1554-1557.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ondondo BO, Rowland-Jones SL, Dorrell L, Peterson K, Cotten M, Whittle H, Jaye A. Comprehensive analysis of HIV Gag-specific IFN-gamma response in HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected asymptomatic patients from a clinical cohort in The Gambia. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3549–3560. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foxall RB, Cortesao CS, Albuquerque AS, Soares RS, Victorino RM, Sousa AE. Gag-specific CD4+ T-cell frequency is inversely correlated with proviral load and directly correlated with immune activation in infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) but not HIV-1. J Virol. 2008;82:9795–9799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01217-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng NN, Kiviat NB, Sow PS, Hawes SE, Wilson A, Diallo-Agne H, Critchlow CW, Gottlieb GS, Musey L, McElrath MJ. Comparison of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific T-cell responses in HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected individuals in Senegal. J Virol. 2004;78:13934–13942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13934-13942.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duvall MG, Jaye A, Dong T, Brenchley JM, Alabi AS, Jeffries DJ, van der Sande M, Togun TO, McConkey SJ, Douek DC, McMichael AJ, Whittle HC, Koup RA, Rowland-Jones SL. Maintenance of HIV-specific CD4+ T cell help distinguishes HIV-2 from HIV-1 infection. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2006;176:6973–6981. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sousa AE, Chaves AF, Loureiro A, Victorino RM. Comparison of the frequency of interleukin (IL)-2-, interferon-gamma-, and IL-4-producing T cells in 2 diseases, human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2, with distinct clinical outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:552–559. doi: 10.1086/322804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duvall MG, Precopio ML, Ambrozak DA, Jaye A, McMichael AJ, Whittle HC, Roederer M, Rowland-Jones SL, Koup RA. Polyfunctional T cell responses are a hallmark of HIV-2 infection. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:350–363. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Silva TI, Peng YC, Leligdowicz A, Zaidi I, Li L, Griffin H, Blais ME, Vincent T, Saraiva M, Yindom LM, van Tienen C, Easterbrook P, Jaye A, Whittle H, Dong T, Rowland-Jones SL. Correlates of T-cell-mediated viral control and phenotype of CD8(+) T cells in HIV-2, a naturally contained human retroviral infection. Blood. 2013;121:4330–4339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-472787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bangham CR. CTL quality and the control of human retroviral infections. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1700–1712. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widner B, Werner ER, Schennach H, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Simultaneous measurement of serum tryptophan and kynurenine by HPLC. Clin Chem. 1997;43:2424–2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beignon AS, McKenna K, Skoberne M, Manches O, DaSilva I, Kavanagh DG, Larsson M, Gorelick RJ, Lifson JD, Bhardwaj N. Endocytosis of HIV-1 activates plasmacytoid dendritic cells via Toll-like receptor-viral RNA interactions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3265–3275. doi: 10.1172/JCI26032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herbeuval JP, Hardy AW, Boasso A, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Dy M, Shearer GM. Regulation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand on primary CD4+ T cells by HIV-1: role of type I IFN-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13974–13979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505251102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien M, Manches O, Sabado RL, Baranda SJ, Wang Y, Marie I, Rolnitzky L, Markowitz M, Margolis DM, Levy D, Bhardwaj N. Spatiotemporal trafficking of HIV in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells defines a persistently IFN-alpha-producing and partially matured phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1088–1101. doi: 10.1172/JCI44960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaehn PS, Zaenker KS, Schmitz J, Dzionek A. Functional dichotomy of plasmacytoid dendritic cells: antigen-specific activation of T cells versus production of type I interferon. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1822–1832. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leligdowicz A, Yindom LM, Onyango C, Sarge-Njie R, Alabi A, Cotten M, Vincent T, da Costa C, Aaby P, Jaye A, Dong T, McMichael A, Whittle H, Rowland-Jones S. Robust Gag-specific T cell responses characterize viremia control in HIV-2 infection. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3067–3074. doi: 10.1172/JCI32380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machuca A, Ding L, Taffs R, Lee S, Wood O, Hu J, Hewlett I. HIV type 2 primary isolates induce a lower degree of apoptosis “in vitro” compared with HIV type 1 primary isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:507–512. doi: 10.1089/088922204323087750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michel P, Balde AT, Roussilhon C, Aribot G, Sarthou JL, Gougeon ML. Reduced immune activation and T cell apoptosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 compared with type 1: correlation of T cell apoptosis with beta2 microglobulin concentration and disease evolution. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:64–75. doi: 10.1086/315170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadowaki N, Antonenko S, Lau JY, Liu YJ. Natural interferon alpha/beta-producing cells link innate and adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:219–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1147–1154. doi: 10.1172/JCI31178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manches O, Munn D, Fallahi A, Lifson J, Chaperot L, Plumas J, Bhardwaj N. HIV-activated human plasmacytoid DCs induce Tregs through an indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3431–3439. doi: 10.1172/JCI34823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsson J, Boasso A, Velilla PA, Zhang R, Vaccari M, Franchini G, Shearer GM, Andersson J, Chougnet C. HIV-1-driven regulatory T-cell accumulation in lymphoid tissues is associated with disease progression in HIV/AIDS. Blood. 2006;108:3808–3817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huengsberg M, Winer JB, Gompels M, Round R, Ross J, Shahmanesh M. Serum kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio increases with progressive disease in HIV-infected patients. Clin Chem. 1998;44:858–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuchs D, Moller AA, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Increased endogenous interferon-gamma and neopterin correlate with increased degradation of tryptophan in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Immunol Lett. 1991;28:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(91)90005-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenna K, Beignon AS, Bhardwaj N. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity. J Virol. 2005;79:17–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.17-27.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boasso A, Shearer GM. Chronic innate immune activation as a cause of HIV-1 immunopathogenesis. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herbeuval JP, Grivel JC, Boasso A, Hardy AW, Chougnet C, Dolan MJ, Yagita H, Lifson JD, Shearer GM. CD4+ T-cell death induced by infectious and noninfectious HIV-1: role of type 1 interferon-dependent, TRAIL/DR5-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 2005;106:3524–3531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baenziger S, Heikenwalder M, Johansen P, Schlaepfer E, Hofer U, Miller RC, Diemand S, Honda K, Kundig TM, Aguzzi A, Speck RF. Triggering TLR7 in mice induces immune activation and lymphoid system disruption, resembling HIV-mediated pathology. Blood. 2009;113:377–388. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraietta JA, Mueller YM, Yang G, Boesteanu AC, Gracias DT, Do DH, Hope JL, Kathuria N, McGettigan SE, Lewis MG, Giavedoni LD, Jacobson JM, Katsikis PD. Type I interferon upregulates Bak and contributes to T cell loss during human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003658. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kader M, Smith AP, Guiducci C, Wonderlich ER, Normolle D, Watkins SC, Barrat FJ, Barratt-Boyes SM. Blocking TLR7- and TLR9-mediated IFN-alpha Production by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Does Not Diminish Immune Activation in Early SIV Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003530. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Creagh EM, O’Neill LA. TLRs, NLRs and RLRs: a trinity of pathogen sensors that co-operate in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harman AN, Lai J, Turville S, Samarajiwa S, Gray L, Marsden V, Mercier SK, Jones K, Nasr N, Rustagi A, Cumming H, Donaghy H, Mak J, Gale M, Jr., Churchill M, Hertzog P, Cunningham AL. HIV infection of dendritic cells subverts the IFN induction pathway via IRF-1 and inhibits type 1 IFN production. Blood. 2011;118:298–308. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-297721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esbjornsson J, Mansson F, Kvist A, Isberg PE, Nowroozalizadeh S, Biague AJ, da Silva ZJ, Jansson M, Fenyo EM, Norrgren H, Medstrand P. Inhibition of HIV-1 Disease Progression by Contemporaneous HIV-2 Infection. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:224–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.