I. THE ORIGINS OF THE WAR ON POVERTY

In his January 1964 State of the Union address, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “War on Poverty”; in August of that same year the Economic Opportunity Act was signed. This legislation was created by the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to design and oversee the plethora of programs that ultimately became the agents of that “war.” Numerous other programs were also developed and enacted as part of the War on Poverty, Great Society effort.

The origin of the War on Poverty can be traced to a memorandum prepared in May 1963 by Walter Heller for President John F. Kennedy. In his memo, Heller demonstrated that the decline in the number of families who were poor (defined as income below $3,000) slowed from an annual average reduction of 1.0 percent during 1945 to 1955 to 0.4 percent between 1956 and 1960. He argued that even with full employment, important groups (e.g., the aged, the disabled, and female-headed families) would remain poor by this standard. President Kennedy followed the memo by instructing staff at the primary executive agencies to make the case for a major effort against poverty.

While the nation had no clear and unified view of the problem of poverty at this time, influential writings in the early-1960s built public support for some form of federal government effort to reduce poverty. These include the revealing 1962 book by Michael Harrington (The Other America) and an eye-opening article on the “invisible poor” by Dwight MacDonald (1963). Both authors built upon the earlier case for public sector action against poverty made by John Kenneth Galbraith (1958). Following the Civil Rights March of August 1963 led by Martin Luther King, which sought racial equality for black Americans at a time when more than 40 percent of blacks lived in poverty, President Kennedy directed that antipoverty measures be included in his 1964 legislative program.

After President Kennedy's tragic assassination, President Johnson sustained this antipoverty momentum and directed that the 1964 Economic Report of the President include a chapter profiling the problem of poverty, and documenting the characteristics of those who were poor. That chapter, which concluded with a series of antipoverty proposals, stands as a landmark of policy analysis to this day.

The report triggered a flurry of activity by the President, who appointed a 130-member White House-based Task Force (headed by Sargent Shriver), and requested them to draft a legislative program modeled on the proposals in the report. The economics-inclined policy analysts on the Task Force pushed for job training programs targeted on disadvantaged youth and remedial education for high school dropouts—a human capital investment strategy that still reflects current policy concerns. A second group of Task Force analysts focused on the “pathology” of poverty—the notion that the heart of the poverty problem rested in the community.1 Their plans for a community action plan designed to mobilize low-income communities and encourage the “maximum feasible participation” of community residents also found their way into the 1966 five-year antipoverty plan submitted by the Task Force.

The Economic Opportunity Bill and its proposed antipoverty budget were complete within six weeks of the appointment of the Task Force and were signed into law in August 1964. A new Executive agency, the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), was established to oversee the effort and to administer some of the programs.

In the years before 1964, the federal government assisted low-income families by providing cash assistance to mother-only families (e.g., welfare in the form of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC] program) and supporting small programs providing in-kind aid (e.g., the Section 236 leased housing subsidy program, which preceded the current Section 8 housing voucher program). The War itself focused on programs that (1) directly provided services to the poor (e.g., legal and medical services); (2) promoted the development of human capital; and (3) stimulated social and community change. Other legislation passed at about the same time provided health insurance to the poor (Medicaid) and (with the support of the farming community concerned about food surplus) expanded a small Food Stamp Program. Housing subsidies were expanded (again with producer support), as were retirement and disability pensions. Many of these new programs were targeted on vulnerable groups with the highest rates of poverty.

Many of the programs first enacted during this period continue in some form today. These programs include the Job Corps (providing vocational training to youth dropouts); the Neighborhood Youth Corps (which offered work experience in low-level public employment jobs for youth who had dropped out of high school or who were likely to drop out); the Community Action Program (CAP, which coordinated the delivery of services in low-income neighborhoods); Upward Bound (providing college preparatory services to disadvantaged minority youth); Head Start (centers offering educational activities for four- and five-year-old children from disadvantaged families); and the Work Experience Program (a work and training program for welfare recipients or those eligible for welfare). In the first year of OEO's existence, over $800 million (1964) was appropriated to the agency for program support; in today's dollars that is nearly $6 billion.

Somewhat later, in the early 1970s, additional major programs were introduced, such as the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program for low-income aged families and low-income families with blind and disabled members, and a small Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which provided a refundable tax credit to families with earnings below a maximum level. While these programs were begun after the initial War on Poverty effort, they are among the central antipoverty measures in place today. We will summarize them in our assessment of all major antipoverty programs.

Thousands of gallons of ink have been devoted to describing the nature of the War on Poverty and analyzing the effects of the War and related legislation. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of this unique outburst of social legislation, several reviews and assessments have been made of the War.2 We will not rework this discussion; rather, we will focus on the following four questions relevant to understanding the War and its impacts:

How has the nature of public policy targeted on poor people evolved over the past 50 years?

How has the measurement of poverty changed over this period?

How has the size and composition of the poor population changed over this period, and what factors account for this change?

How did the War on Poverty and subsequent government antipoverty programs affect the prevalence of poverty, and how has that effort waxed and waned over this half-century?

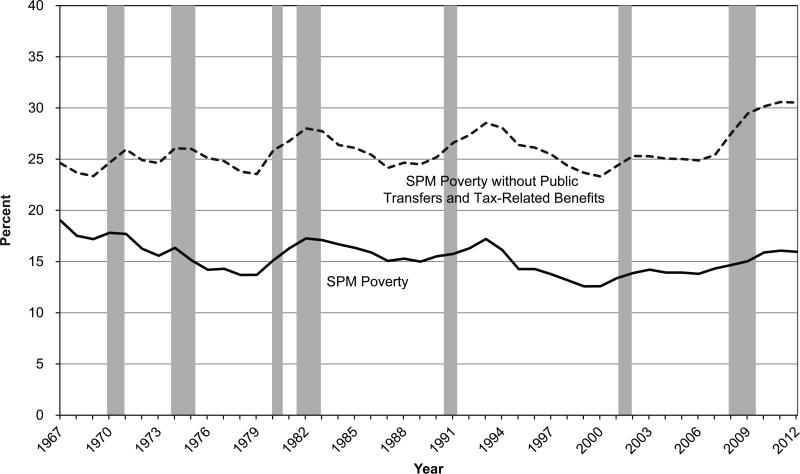

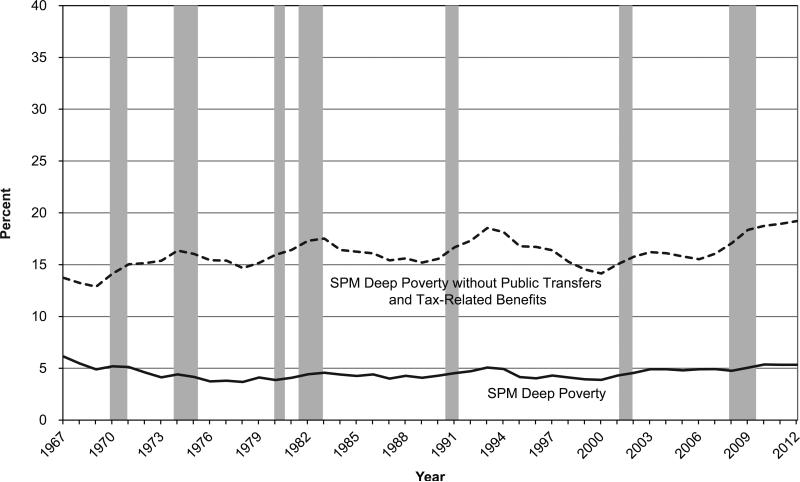

Our first section describes how public policy has evolved since the War on Poverty, particularly in the direction of a much greater emphasis on work as a condition of benefit receipt and on in-kind rather than cash transfers. Our second section shows that while the official definition of poverty was adequate in the early 1960s when it was developed, it has become increasingly deficient. This has a major effect on interpreting the evolution of the prevalence of poverty in the years after the War on Poverty. While the official poverty rate suggests that poverty has not declined since the late 1960s, improved definitions, which include the impacts of noncash benefits and refundable tax credits like the EITC, show that policy has in fact had a major impact on poverty. In the subsequent section, we show that despite gains in overall poverty reduction, many subgroups continue to have very high poverty rates. For these groups, the War on Poverty programs have not reduced poverty to acceptable levels. The final section shows that the growth in antipoverty spending is responsible for the decline in poverty rates since 1969—poverty would not have declined in its absence. While the War on Poverty programs have not yet yielded “victory,” a number of important battles have been won. However, since the mid-1990s the distribution of spending on low-income families has tilted away from the poorest of the poor, leading to a declining impact of spending on deep poverty. As a result, deep poverty rates have not declined for the past 20 years, unlike overall poverty rates.

II. THE EVOLUTION OF POVERTY POLICY OVER 50 YEARS

President Kennedy was heavily influenced by the debate stimulated by the Harrington and MacDonald writings in the early-1960s, and initiated discussions of antipoverty policy during his term. But the War on Poverty itself, as we have described, was launched in a period of national soul-searching after the death of President Kennedy. President Johnson pursued the civil/voting rights and social policy revolutions when he assumed the presidency in November 1963 in the optimistic belief that the country should and could address the assortment of problems surrounding poverty, including the nation's racial issues and serious shortfalls from basic civil rights.3 At that time, about 20 percent of Americans were classified as living in poverty.

In this section, we describe in broad-brush terms changes in federal antipoverty policy over the 50 years since 1965. The central story is the steady shift over this period from income support to those without other income (in the form of means-tested cash welfare like the AFDC program) to programs that emphasized work and labor force participation (like the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC]). There was also a shift from cash income support to in-kind benefits, such as Food Stamps and especially Medicaid.4

A. From 1965 to 1975: Providing Legal/Medical Services, Developing Human Capital, and Stimulating Community Change

Prior to the initiation of the War on Poverty, one-fifth of the nation's 47 million families lived in poverty (defined at that time as pretax cash income less than $3,000). More than a million families below this income level were raising four or more children. Certain socioeconomic groups experienced much higher poverty rates, including those with family heads with the following characteristics:

Nonwhite (48 percent)

Persons with less than 8 years of education (37 percent)

Females or single parents (48 percent), especially those with low education (89 percent for nonwhites, 77 percent for whites)

Persons aged 65 or more (47 percent) or less than 25 years (31 percent)

Non-earners (81 percent)

Farm residents (43 percent)

Those living in the South (32 percent)

For persons living in families headed by someone with any of these characteristics, poverty rates were more than 150 percent of the overall poverty rate of 20 percent.5

With Walter Heller as head of the Council of Economic Advisors under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, fiscal measures to expand aggregate demand and employment flourished as a rising tide was viewed as lifting all boats. During this period, wages and real earnings rose throughout the earnings and income distributions.

The set of programs benefiting low-income families that were initiated or expanded around the mid-1960s is extensive.6 As described above, the range of the OEO effort itself was very broad. Two direct service programs stand out. The Legal Services program was a novel attempt to provide legal services to poor families, and to change social institutions. Legal services lawyers in 250 legal services projects not only provided direct legal advice to poor families, but also led national legal reform efforts through the bringing of test cases and class action suits in the housing, medical, and consumer rights areas. The OEO neighborhood health centers program attempted to provide comprehensive medical and dental care in areas where the poor lived; by 1972 the budget for these centers had grown to about $750 million (2014 dollars).

Efforts to build the human capital of poor and minority individuals were also extensive. Job training programs targeted on disadvantaged youth and high school dropouts (e.g., the Job Corps and the Neighborhood Youth Corps) formed one of the main thrusts of early antipoverty policy. In addition, the Manpower Development and Training Act of 1962 (MDTA), the first major piece of manpower legislation since the Employment Act of 1946, inaugurated substantial job training efforts targeted on both poor and middle class unemployed workers.

Although job creation and skill-building for the underemployed were emphasized early in the War, there was little emphasis on expanding higher education, reflecting the modest education earnings premium that existed at this time. The Head Start program was the main early education program and served four- and five-year-old children in disadvantaged families; by the summer of 1965 over one-half million children were enrolled.7

Major efforts to generate community change were also begun in the mid-1960s. The Legal Services program was a component of this; the Community Action Program (CAP) was more central to this effort by both coordinating existing services to families in poor neighborhoods and delivering new services to them. The program became the home for a number of activists and left-leaning community organizers, whose objective was to generate social change by giving the poor a role in the programs that affected them. The CAP was among the most controversial programs of the War; some have accused the program of being responsible for the riots in the summers of 1966 and 1967.8 The Model Cities program provided block grants to cities to plan and implement development projects in physically blighted local areas—urban renewal. City officials rather than neighborhood associations were in charge of the program so that the program was seen as a less disruptive alternative to the CAP.

In addition to the OEO-related programs, numerous other programs targeted on the poor population were expanded in the years immediately after the declaration of the War. Importantly, during this period, the Medicaid and Medicare programs (providing health insurance for the poor and elderly, respectively) were inaugurated. Both passed in 1965 as extensions of the Social Security program. Cash income support through the AFDC program was viewed as an important instrument in reducing poverty for families headed by single mothers—who were still a relatively small group composed primarily of divorced rather than never-married mothers or widows. At this time, single parents were viewed as “worthy” safety-net beneficiaries. Similarly, the Food Stamp Program (characterized as a “universal guaranteed annual income for food”) was mandated in all counties; prior to that, it was not universal. The Section 8 housing subsidy program was also expanded. During this same period, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 had become the law of the land, leading to increased spending targeted on K-12 schools. In 1967, earnings deductions were increased in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, reducing work disincentives and expanding the caseload; this change was known as the “30-and-a-third” rule.9

In the years after 1969, when President Richard Nixon assumed the presidency, expenditures and benefits targeted on poor families continued to increase, encouraged and supported by the OEO-based coordinated legal strategy that promoted “welfare rights” and access to public support. However, President Nixon sought to fundamentally change the emphasis of social policy expansion. Benefits to elderly and disabled people, two groups not expected to work, were expanded. In 1972, an across-the-board increase of 20 percent in Social Security benefits was passed. When coupled with an annual automatic cost of living increase, this one-time benefit expansion led to a sizable increase in income support to elders. In 1974, legislation to support the needy aged, blind, and disabled through converting state-specific programs for each of these groups into a national Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program with a national guaranteed minimum income became law. The combination of these measures contributed in a powerful way toward reducing poverty for the aged and disabled population. Today, the “official” poverty rate for citizens older than 65 years is well below 10 percent, and a series of extensions of coverage and benefit increases has resulted in Social Security being our most effective antipoverty program.10

Shortly after assuming office, President Nixon announced the Family Assistance Plan (FAP), promoted by Daniel P. Moynihan, then his Assistant for Urban Affairs, over the opposition of many of the President's most conservative advisers (see Moynihan, 1973). It would meet the problem of poverty with the most direct and radical of solutions: money. All families with children would be eligible for a minimum stipend; no longer would the absence of a “man in the house” be a precondition for welfare income support. After passage by the House of Representatives, the measure failed in the Senate, in part because of concerns about work incentives.

Already in the late-1960s, there was a growing concern about the work disincentives built into cash transfer programs. The landmark 30-and-a-third legislation for AFDC was the first movement toward increasing work incentives. This effort was viewed as a failure by President Reagan and was eliminated; the “tax rate” in the welfare program (that is, the rate at which benefits fall as income rises) returned to 100 percent. In the late-1960s and 1970s, consistent with concern over the 100 percent tax rate on earnings, the federal government sponsored a number of important social experiments on the ways that income support policies affected labor supply and work effort. These experiments revealed the extent of work disincentives implicit in a variety of income support policies.11 The experiments also gathered a great deal of information about how income support and work affected children, educational attainment, and other aspects of family life, even if they were not analyzed until decades later.12 During the Nixon era, several of the programs composing the War were subject to evaluation studies; many of these studies failed to find social benefits that exceeded costs.13 This is especially true of the human capital and community participation programs. The impacts of these programs are difficult to measure, however, and some of the effects can only be expected to appear over subsequent decades.14

Public spending on these and other War on Poverty, Great Society programs grew from $45 billion in 1965 to $140 billion in 1972 (both in 2014 dollars). Social benefits15 as a percentage of personal income increased from about 6 percent in 1965 to over 10 percent in 1975.

By the mid-1970s, substantial progress against poverty was made and poverty rates of under 10 percent were seen for the first time, especially after counting non-cash benefits as part of income (Smeeding, 1977; Fox et al., 2014; CEA, 2014). The labor market continued to spread the benefits of economic growth to all workers, and longtime leaders of the War on Poverty, like Robert Lampman, foresaw an end to poverty and material deprivation within a decade. 16

To a substantial extent, War on Poverty programs appear to have targeted those groups with the highest pre-1965 poverty rates; the decrease in the probability of being poor fell more for these high-poverty-rate families than for families with a lower incidence of poverty. Table 1 depicts patterns that indicate the incidence of poverty in 1965 and 1972 for a variety of family types, distinguished by race, region, education, and sex of family head (in percentages).

Table 1.

Percent of persons in families with income below the Federal Poverty Line, 1965 and 1972

| 1965 | 1972 | Percentage point change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All persons | 15.6 | 11.9 | −3.7 |

| 0-8 years of schooling | 30.8 | 23.0 | −7.8 |

| Nonwhite male | 35.8 | 19.5 | −16.3 |

| Nonwhite female | 66.2 | 57.4 | −8.8 |

| Age 65 and older | 27.6 | 19.2 | −8.4 |

| South | 24.5 | 17.0 | −7.5 |

| Rural | 23.8 | 15.4 | −8.4 |

| Black female head with children* | 77.0 | 70.0 | −7.0 |

| Southern, low education, black male head* | 64.0 | 55.0 | −9.0 |

| Black urban elderly couple* | 65.0 | 51.0 | −14.0 |

Predicted probability of being poor

While the incidence of poverty for all Americans decreased by 3.7 percentage points between 1965 and 1972, poverty for these vulnerable groups targeted by War on Poverty programs decreased by 7.0 percentage points to 16.3 percentage points. All of the percentage point decreases shown are at least double the overall decrease in poverty incidence. Hence, to the extent that the programs and expansions launched in the mid-1960s were designed to lower poverty among the highest-poverty-rate groups shown in Table 1, this objective was met in the immediate years that followed.

B. From 1975 to 1985: Sagging Economy, Reassessment of Early Antipoverty Programs, Decline in Cash Income Support, and Emphasis on Work

The decade from 1975 to 1985 was a difficult economic period. The economy soured, with rising energy prices and high inflation coexisting with slow growth. Benefit cuts in some social programs occurred as skepticism toward early War on Poverty initiatives grew. During the same period, the job market for lower-skilled workers deteriorated, inequality of wages and earnings increased, and the rate of nonmarital childbearing rose. In part as a result of these developments, the steady progress in fighting poverty that occurred following 1965 slowed markedly.

Based on evaluation studies, early efforts to provide job training were viewed with skepticism. In response to labor market deterioration, the EITC was inaugurated and the Food Stamp Program expanded. In 1979, the Food Stamp Program's “purchase requirement”—a feature of the initial program—was lifted, increasing access to food assistance.17 At the program's start in 1965, about half a million people participated. Through publicity and the geographic expansion of the program, participation increased to about 15 million people in 1974. After elimination of the purchase requirement, participation in the program increased by 1.5 million people in a single month (Ziliak, 2013).

The late-1970s and early-1980s also brought major changes in labor markets. During the high inflation and low economic growth “stagflation” period, unemployment of lower-skilled workers increased, resulting in reductions in earnings and income in the bottom half of the distribution. Technological change stimulated demand for educated workers, at the same time that the supply of college-educated workers slowed. As a result, the college premium rose substantially; while Richard Freeman could write about The Overeducated American in 1976, by the mid-1980s this was no longer true (Autor, 2014).

The toll on workers with few skills was large18 and this, in part, justified passage of the EITC in 1975. The EITC began as a small program providing earnings supplementation to low-earnings workers through a refundable earnings-related subsidy.19 Passage of the EITC is related to the failure of President Nixon's FAP; Senator Russell Long opposed FAP because of the work disincentives, and supported a “work bonus,” which eventually became the EITC. Public support of both the EITC and the New Jobs Tax Credit of 1977 to 1979 (which subsidized the creation of jobs for low-wage workers) represented a focus on work rather than income support.

During this same period, enthusiasm for federal government efforts to provide job training also waned. The Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) was initiated in 1973. CETA emphasized public sector employment for those with low incomes and the long-term unemployed, as well as subsidized jobs in the private sector, in which the employer was reimbursed for job training costs. The intent was to impart a marketable skill that would allow participants to move to an unsubsidized job. Evaluations of CETA were not favorable, leading to a search for alternative ways of improving the earnings performance of low-skill workers.20 In the late 1970s, the Carter Administration proposed the Program for Better Jobs and Income welfare reform. The proposal had a massive public jobs component integrated with an earnings supplement with income-conditioned cash assistance, and extended cash benefits to individuals and intact families. The proposal failed, and its failure contributed to the demise of federal job creation efforts. (See Danziger, Haveman, & Smolensky, 1977.)

These policy debates were affected by large changes in social behavior that were visible in nascent form in the late 1960s, but which accelerated in the 1970s and early 1980s. The rate of nonmarital childbearing began to increase, divorce rates increased, and women began entering the labor force in increasing numbers. The rate of nonmarital childbearing grew from about 15 percent of all births in the 1970s, to over 25 percent by the mid-1980s.21 Out-of-wedlock childbearing became an important determinant of the high rate of poverty for female-headed families, and AFDC budgets grew rapidly. At the start of the War on Poverty, female-headed families constituted about 8 percent of all families; by 1980, about 17 percent of families with children under age 18 were headed by a woman. In 2013, the rate was about 23 percent. But at the same time more women, especially mothers, entered and remained in the formal labor market, leading to a change in mores about mothers’ role in formal work.22 During the 20-year period from 1970 to 1990, the labor force participation rate for women increased by 14.2 percentage points.

However, the main issue in the 1980 presidential election that resulted in the election of Ronald Reagan was the performance of the economy. Triggered by the OPEC oil embargo in 1973, the price of oil quadrupled. This price spike triggered a long period of stagflation. Wage and price controls were among the set of unpopular policies used to slow down inflation by Presidents Nixon and Carter.

During the period leading up to the Reagan election in 1980, the gains in the economic status of the poor that resulted from earlier antipoverty efforts largely held. However, the poverty rate began to drift up in the late 1970s and during the stagflation period that ensued.

In the early-1980s, the Reagan administration supported the tight money policy of the Federal Reserve designed to deliberately slow down economic growth in order to squeeze inflation out of the economy. While overall federal spending continued to grow, administration priorities shifted emphasis from social policy spending to other spending programs, including assistance to state governments; the role of adverse work incentives was cited.

The substantial Reagan tax cuts23 were tilted toward higher income earners and led to an increasing deficit. Legislation during this period enabled states to obtain waivers in order to implement changes in the AFDC program typically involving reduced cash benefits and strengthened work requirements. The motto of the era was “trickle down,” which promised that the poor would benefit from economic growth, even if there were cuts to social spending. CETA was replaced by the Job Training Partnership Act of 1982 (JTPA), which concentrated on private sector employment and which established federal assistance programs to prepare youth and unskilled adults for entry into private employment and out of welfare dependence; the program gave more control to states to help build partnerships with private industries (local employer organizations known as Private Industry Councils or PICs). Evaluations of JTPA, like those of CETA, were not very favorable (see Bloom, 1987). During this turbulent period, two programs—the EITC and Food Stamps—grew in importance, reflecting both expanded benefits and reduced application costs; they have become and are expected to continue as the bedrocks of income support in the United States (Hardy, Smeeding, & Ziliak, 2015).24

Social benefits as a percentage of personal income began the decade from 1975 to 1985 at about 10 percent and they edged up only a single percentage point over the period.

C. From 1985 to 2000: Work-Based Reform and Retrenchment

The period from 1985 through the 1990s combined reform and retrenchment. Concerns over the growth in mother-only families and inner-city poverty led policymakers to focus more on behaviors—including work—than on deprivation. In response to growing evidence that income support policies had substantial work disincentives and generated reductions in work effort, work-based welfare reform passed, and to support the new focus on work, child care benefits were expanded.

Toward the end of the 1980s, several scholars and opinion leaders reflected on the apparent contradiction between the main thrust of antipoverty policy and the changing nature of the poor population (see Ellwood, 1988; and Wilson, 1987). During the 1980s, the nature of the poor population changed in important ways; already-high rates of nonmarital childbearing increased further, increasingly the poor were living in inner-city ghettos, and an urban underclass developed and grew.25 The “underclass” concept came into popular use and became a synonym, not of poverty, but of a set of behaviors in which inner-city residents eschewed traditional work and schooling, and engaged in behaviors that imposed costs on the rest of society (Jencks, 1989; Ricketts & Sawhill, 1988).26

The Family Support Act of 1988 (FSA), passed at the end of the Reagan administration, responded to these concerns. The structure of the AFDC program was modified to emphasize work, child support, and family benefits; it also initiated the withholding of wages of absentee parents liable for child support. The law required teen mothers who receive public assistance to remain in high school and, in some cases, to live with their parents. The Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Training program (JOBS), created by the 1988 Act, created incentives and mandates for moving from welfare to work.27

President Reagan was succeeded by President George H. W. Bush in 1989. There were but few changes in the thrust of poverty policy during the Bush presidency with one exception; the EITC was expanded in 1990. In 1993, under President Bill Clinton, the EITC was expanded again, as part of general federal tax legislation. Both expansions were designed to increase the targeting of assistance though a tax rebate while increasing the incentive to work. Researchers found that EITC expansions were among the most important reasons why employment rose among single mothers with children during the 1990s—the EITC was more effective in encouraging work than either welfare reform or the strong economy.28 The Committee for Economic Development, an organization of 250 corporate executives and university presidents, concluded in 2000 that, “The EITC has become a powerful force in dramatically raising the employment of low-income women in recent years.”29

The 1990s saw a rapid increase in the use of illicit drugs, especially cocaine, often by minority poor youth. The “drug epidemic”30 fostered extreme penal policies that incarcerated nonwhite undereducated men especially, separating them from families and greatly reduced the chances of gainful legal employment upon release. The effect of penal policy during this period is reflected in the high black male poverty rates experienced today. At the same time, labor markets increasingly rewarded the educated; earnings inequality continued to increase; wages and employment for the less-skilled eroded further (Autor, 2014).

Elected in 1992, President Clinton often spoke about the Wilson and Ellwood thesis. After the failed effort to reform health care, he turned to welfare reform, in part responding to the newly elected 1994 Congress, which regularly decried the growth in welfre rolls and costs.

In 1996, the Clinton welfare reform with the unruly title of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) was enacted. The 1996 Act reflected many of the perspectives of Wilson and Ellwood and the skepticism of Murray. Moreover, the FSA was widely regarded as having failed to either diminish the work disincentives in welfare programs or to produce improved labor market outcomes through its human capital-training emphasis. These perceptions supported the brute force approach in PRWORA—“welfare as we knew it” became a thing of the past.

PRWORA ended the entitlement to AFDC benefits and turned AFDC expenditures into block grants that were given to the states with a new name, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Recipients of TANF benefits were required to begin working after two years of benefit receipt and a lifetime limit of five years was placed on benefits paid by federal funds.31 The legislation also supported programs that encouraged two-parent families and discouraged out-of-wedlock births32; the enforcement of child support payments was given teeth. The success or failure of the “Clinton welfare reform” has been heavily debated.33

As a result of PRWORA, welfare rolls plummeted from over 5 million cases in 1993 to fewer than 2.5 million cases in 2000. The work requirements of PRWORA, together with the EITC expansions and the very strong economic expansion in the mid-1990s, led to rising employment rates for single mothers and declining poverty rates.34 However, the late-1990s saw a leveling off of the employment rates of single mothers and little change in their poverty rate as single mothers moved from below-poverty cash income support to low-wage labor market work that typically also left them below the poverty line.35 In the long run, PRWORA appears to have had a greater impact on reducing the caseload rather than on increasing employment rates or reducing poverty.

The 1990s also saw a rapid increase in child care subsidies and early childhood education programs (including Head Start); this too eased the transition of low-income women into the labor force. This period also witnessed a rapid rise in disability rolls in both the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and in programs for disabled children and the non-aged (Muller, 2006).

In 1997, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was passed, in part as fallout from the failed Clinton effort to reform the health care system and the desire to make health insurance available to all children. CHIP was the largest expansion of taxpayer-funded health insurance coverage for children in the United States since the Medicaid program was established in 1965.36 CHIP provides matching funds to states for health insurance to uninsured families with children with incomes that are modest but too high to qualify for Medicaid. Today, CHIP covers about 8 million children, and every state has an approved plan.

By the new millennium, the basic structure of federal antipoverty policy was much as we see it today. The TANF block grants were never expanded and expenditures on the program have grown only slightly, with virtually no enrollment increase during the Great Recession. As envisioned in PRWORA, states used some TANF funds to expand child care and job training and to add state supplements to the EITC; by the year 2011, less than $10 billion of cash welfare benefits were paid and the TANF rolls dipped to about 2.3 million cases. The income support system had evolved into one largely based on work.

During this period, social benefits as a percentage of personal income increased by only 1 percentage point, from 11 percent to about 12 percent.

D. From 2000 to Now: Large Expansion; Little Reform

Since the millennium, public programs supporting low-income families have grown, with most of this growth coming during the latter part of this period. During the George W. Bush presidency, few changes were made to the structure of the nation's antipoverty effort. The 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts expanded the Child Tax Credit from $500 per child to $1,000 and made it partly refundable. Both efforts added support to the EITC in encouraging work. At the same time, support for job training programs continued to erode as states took a “work-first” approach to income support. Those without earnings due to joblessness, disability, or mental illness had no recourse except for the SSI program, which also expanded but nonetheless failed to enroll all of the eligible population; homelessness rose as a national scourge.

During the early 2000s, researchers began describing those who could not hold work as the “disconnected” (those not in work, education, or on welfare) and speculated about how they could be supported. As a result, the disconnected began to emerge as a national policy issue in the 2000s (Blank, 2009).

The election of President Barack Obama in 2008 coincided with the worst recession the economy has seen since the Great Depression. The country was saddled with a work-based safety net at the same time that jobs dried up. Two programs proposed by the administration and enacted by Congress contained important provisions assisting the low-income population—the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

While the primary objective of the $800 billion ARRA was to save and quickly create jobs, the Act also provided temporary relief for those most affected by the recession. The Act contained a “Making Work Pay” income tax credit of $400 per worker and $800 per couple in 2009 and 2010 targeted on low- and middle-class families, and an untargeted 2 percentage point cut in payroll taxes for all workers in 2011 and through February 2012. The ARRA also expanded the EITC for families with at least three children; increased Medicaid spending; expanded Pell grants, Head Start, and child-care services; extended unemployment benefits; and expanded benefits in the Food Stamp Program by 14 percent.37 It provided a one-time $250 payment to Social Security recipients, people on Supplemental Security Income, and veterans receiving disability and pensions. The total appropriation for just those pro-poor programs mentioned equaled nearly $300 billion. Because of these expenditures targeted on lower-income families, the poverty rate rose far less than it would have in the absence of these programs (discussed more below).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Obama health care reform—also provided substantial assistance to low-income families. Medicaid benefits were again expanded38 and those with low to moderate incomes received subsidies to obtain increased coverage and access, typically through the purchase of health insurance through state-based exchanges. In addition, the funding of Community Health Centers was expanded,39 and eligibility for the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was extended (see Haveman & Wolfe, 2010).40 As a result, the percentage of those without health insurance coverage has decreased substantially—by at least 5 percentage points, from about 20 percent to about 15 percent—from 2012 to 2014. (See Sommers et al., 2014.)

Despite the expansion of existing income support and other targeted policies, out-of-wedlock childbirth rates increased from 33 percent in 2000 to over 40 percent in 2012. In part this is due to the decline in marriage rates among those with less than a college degree, and a related increase in rates of cohabitation. For Hispanics, about 54 percent of births are to unmarried women and for blacks nonmarried births are about 72 percent of all births. (See Martin et al., 2013; and Solomon-Fears, 2014.)

At the same time as child support began to be more strictly enforced, the phenomenon of multi-partner fertility emerged, where children born to multiple fathers lived with their (typically single) mother, and became a policy issue (Carlson & Meyer, 2014). In addition, in the face of a weak recovery from the Great Recession, the Social Security Disability Insurance program (SSDI) continued to grow.

Perhaps most importantly, as the nation slowly emerged from the recession, most of the jobs created were low-skill, low-wage service jobs that do not have health or pension benefits (NELP, 2014). With low wages, pressure for an increase in the minimum wage grew. The EITC, CTC, and Food Stamp Program (since 2008, known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) remained the cornerstones of the income support system; in 2013, expenditures on each of these programs totaled more than $80 billion.

As a result of a slower economy with higher unemployment, and program expansions designed to address these problems, social benefits as a percentage of personal income expanded from about 12 percent to 17 percent during this period.

E. A Half-Century of Poverty Policy, In Brief

Over the past 50 years then, the nation's view of the poverty problem has changed substantially, as has national government policy toward the poor. In the 1960s, with living standards regularly rising for the large majority of the working-age population, Americans viewed the problem of poverty through a variety of different lenses, and these various perspectives became reflected in the complex War on Poverty legislation passed at this time. These views, combined with the perceived efficacy of social planning by social scientists, whose influence in government was at its peak during this period, resulted in the many-faceted War on Poverty. The War on Poverty program did not have a single coherent strategy. Expansion of cash income support (welfare) was part of the agenda. The provision of Food Stamps and health insurance (Medicaid) was also central to the effort. Training and employment of youths formed a “building human capital” emphasis. Efforts to mobilize communities by involving poor citizens in decisions that affected their neighborhoods were reflected in the legal services and community action programs. The nation seemed enthusiastic about the possibility that the problem of poverty could be effectively addressed.

In spite of a decline in poverty during the first decade after 1965, this belief in the ability of the nation to reduce or eliminate poverty was sorely tested. During the 1970s and 1980s, the structure of the American family changed substantially. Out-of-wedlock childbearing, particularly among low-education, urban minorities, increased; the prevalence of female-headed families grew rapidly. Wage inequality began increasing, a trend that continues to the present.41 The perceived need to support the incomes of low-wage workers led to the passage of a small Earned Income Tax Credit in 1975. Married women began entering the labor market in large numbers in the 1970s (continuing into the 1980s), in part in response to the stagnating wages and declining employment of their low-education, low-skilled male partners, but also in response to work-based changes in welfare policy.

By 1980, there was a backlash against the original War on Poverty efforts—especially, the growth in cash income support. Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980 as stagflation continued to plague the economy. During these years, spending cutbacks, a variety of programs emphasizing the need for work (e.g., work requirements in AFDC, expanded EITC, passage of the FSA and its JOBS program), and the substitution of in-kind for cash assistance characterized federal policy toward the poor.

The 1990s saw the “drug epidemic,” which fostered extreme penal policies that incarcerated nonwhite undereducated men especially. The Clinton-sponsored PRWORA legislation was passed in 1996, ending the entitlement to AFDC benefits and providing states with funding to create TANF programs requiring work and time limits on the receipt of cash benefits. During the Clinton years, child care subsidies and early childhood education programs (including Head Start) and the EITC were expanded, and in 1997, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was passed.

After the millennium, policy discussions turned toward the “disconnected”—those who were not in work, education, or on welfare. Homelessness increased and only the SSI program provided residual aid to this population. Out-of-wedlock birth rates continued to rise, along with multi-partner fertility. In 2008 to 2009, the nation faced enormous job loss during the Great Recession; the work-based safety net was less effective as jobs dried up. After 2008, two signal pieces of legislation affected the poor population: the ACA and the ARRA. Under Obamacare, Medicaid benefits were again expanded and those with low to moderate incomes received subsidies to obtain increased coverage and access through state-based exchanges. The ARRA included both targeted income tax credits to lower-income families, as well as a cut in payroll taxes for all workers.

Since 2008, the EITC for families has been expanded, and spending on Medicaid, Pell grants, Head Start, and child care services, unemployment benefits, and the Food Stamp Program all grew. Nevertheless, the prior shift from cash income support to required work as the basis for benefit receipt eroded the safety net for the most disadvantaged in American society. The growth in programs targeted on the poor did reduce poverty for families with children once refundable tax and in-kind programs are taken into account.42 As the nation slowly emerged from recession after 2009, most of the jobs created were low-skill, low-wage service jobs without health or pension benefits—thus pressure grew for an increase in the minimum wage.

In spite of these major policy shifts from the original War on Poverty program, social benefits as a percentage of personal income increased steadily from 6 percent to 17 percent in the 50 years since 1965.

III. THE MEASUREMENT OF POVERTY: AN EVOLVING STORY

When the War on Poverty was launched, there were no government statistics on poverty and no general agreement about what it meant to be called “poor.” A statistical measure of poverty was needed to indicate how many people were poor, show how the prevalence of poverty was concentrated among different groups, and enable the tracking of the poor population over time. Such a measure could also provide a crude indicator of the effectiveness of antipoverty policies.

A. The Creation of a Poverty Measure in the Johnson Administration

The Johnson administration asked the Social Security Administration (SSA) to propose a poverty definition; an SSA employee, Mollie Orshansky, was put in charge of this project.43 She calculated a poverty threshold that presumes the resource-sharing unit to be the family (defined as two or more related individuals residing in the same dwelling); the threshold for families of two or more in 1963 was based on the following definition:

The subsistence food budget was the Economy Food Plan defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1961; it was described as the funds needed for “Temporary or emergency use when funds are low.” The multiplier of 3 was based on the fact that the average family of two or more spent one-third of their after-tax income on food, as indicated in the 1955 Household Food Consumption Survey; the multiplication of the food budget by 3 indicated the income necessary to support that level of food consumption. To produce poverty thresholds for families of different sizes and configurations, an equivalence scale was used, based on relative food expenditures among different family types.

Over time, these poverty thresholds have been updated annually by changes in the consumer price index—CPI-U—which reflects the price of a basket of goods purchased by typical urban consumers. Aside from these annual threshold updates, there have been very few changes to the 1965 measure, which is often referred to as the “official” poverty line.

To calculate the scope of poverty, it is also necessary to define “family resources” to compare to the poverty threshold to determine if a family is or is not poor. Orshansky used a family's pre-tax cash income; hence, a family whose pre-tax cash income fell below the poverty threshold for a family of their size and configuration would be considered poor.44 The overall poverty rate was calculated as the total number of people living in families whose income was below the poverty threshold, divided by the total population. Separate rates were calculated for different subpopulations (such as by race and ethnicity, age, gender, or family composition).

This poverty calculation has been used since the mid-1960s and is the nation's official poverty measure. It is an “absolute” measure so that if low-income families experience real income growth, an increasing number of them will move above this threshold and the poverty rate would automatically fall. In 1963 the poverty line was about 49 percent of median income, but by the early 2000s it had fallen to less than 30 percent of median income.45

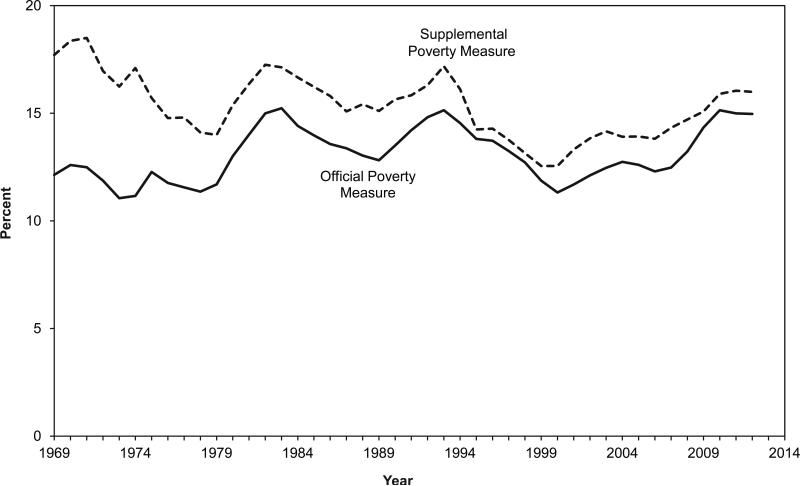

The original presentation of these official poverty rates occurred in the Economic Report of the President (1964).46 The results of Orshansky's measurement efforts are shown in the solid line of Figure 1. While 22.4 percent of the population was poor in 1959, this number fell rapidly to a low of 11.1 percent in 1973. It has never been this low in any year since. After 1973, the poverty rate stagnated, rising in recessions and falling in good times. The last year for which data are available is 2013, when the official poverty rate was 14.5 percent, much higher than in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In short, official poverty rates have shown no noticeable long-term trend in the U.S.--and, in particular, have not declined--for 40 years despite the poverty line as a percentage of median income falling nearly 20 percentage points.47

Figure 1. Poverty Rates, 1969–2012: Official and Supplemental Poverty Measures.

Source: SPM data from Fox et al. (2014); official poverty measure data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

B. Growing Criticisms of the Official Poverty Measure

Within a decade of its creation, the official poverty measure began to be criticized and suggestions for alternative measurement approaches began to be heard. All of its components were questioned—the definition of the resource-sharing unit, the use of pre-tax cash income,48 and the thresholds (which were thought to be too low). With improved data, analysts doubted that the threshold should be benchmarked to food alone. Moreover, the official poverty thresholds were criticized for not reflecting substantial differences in the costs of living across locations or increases in standards of living.49

The absolute nature of the U.S. poverty threshold, based on data from the 1950s and adjusted for inflation over time, means that there is no conceptual justification to the current poverty line; it is simply an arbitrary dollar amount. Using a threshold calculated in 1964 (based on 1950s data) to estimate poverty in 2014 is to use a 50-year-old categorization. Because this measure is based on cash income, it is not affected by the many in-kind antipoverty programs initiated in the U.S. over the past five decades. Because tax measures do not affect the definition of pre-tax income, substantial increases in after-tax income among low-income families due to the several expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) over the years had no impact on the measure of poverty. In essence, the very definition created in the Johnson Administration to help understand poverty has led to serious misunderstandings because of its growing inadequacy over time.

C. Some Progress

Over the years, a variety of formal efforts recognized some of these issues in attempts to update and refine a new and improved poverty measure. In the early 1990s, the poverty measure was formally reviewed by a panel created by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS).50 The NAS panel recommended alterations to the definition of the poverty threshold and adjustment of these thresholds for cost-of-living differences across regions and rural/urban areas. Moreover, the panel recommended a resource definition that measured after-tax income (since taxes are mandatory payments) plus imputed in-kind benefits from major near-cash programs (primarily Food Stamps and housing assistance). The value of health insurance was not imputed but the panel recommended that out-of-pocket expenditures on health care be subtracted from after-tax income, since these resources are not available to be spent on food, shelter, and clothing.51 Work-related expenses, including child care, were also proposed to be subtracted from resources; these were treated as necessary expenditures in order to earn a living.

The NAS recommendations led to substantial body of follow-up research and a few cities or regions have implemented a version of the NAS recommendations.52 Starting in 2011, the U.S. Census Bureau began to regularly report a Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which is loosely based on the NAS recommendations; other alternative poverty measures using more expansive resource definitions, taking account of taxes and in-kind benefits, were also published.53 But neither the SPM nor alternative poverty rates published by the Census Bureau generated sufficient support in Congress to revise the official poverty measure.54

Figure 1 shows the SPM along with the official poverty measure. In addition to pretax cash income, which is the basis for the official measure, the SPM takes into account in-kind benefit programs and benefits conveyed through the tax system in the resource measure. The SPM also deducts work-related expenses and out-of-pocket health-care expenses from income. Because the SPM poverty thresholds are based on expenditures on food, housing, and clothing (rather than just food) and are adjusted over time as the composition of expenditures changes, the SPM is a quasi-relative poverty measure.55 Differences in housing costs between areas are also accounted for, and an improved equivalence scale is used to determine the thresholds for different types of families. The SPM indicates that poverty has declined over time, rather than being essentially flat as the official measure implies.

D. Alternative Approaches to Poverty Measurement

The SPM is an effort to update poverty measurement, but its approach is conceptually similar to Orshansky's with a poverty threshold based on expenditures on necessities and a resource measure based on family resources. There are other approaches to poverty measurement that have been proposed that would measure poverty in fundamentally different ways.56 For example, many have suggested that poverty be defined as the share of the population below some point in the income distribution. Fuchs (1967) and Ruggles (1990) proposed a poverty threshold be set at 50 percent of median income. In contrast to the absolute poverty lines used in the official measure, a relative measure of poverty would remain constant even if all incomes are growing proportionally across the distribution.57

An alternative approach is to define a poverty threshold by estimating the cost of a comprehensive basket of necessary expenditures. Rather than using data on expenditures to determine a poverty threshold, such an approach would require an objective determination of what is “necessary” and what is a “reasonable cost” for those things deemed necessary. There have been efforts to create such baskets for the United States.58 The European Union (EU) has recently funded several major research projects designed to create low-income expenditure baskets and compare the resulting poverty measure to other approaches.

A further alternative is focused on using expenditure data rather than income data in calculating the resource side of the poverty measure. Of course, this requires reliable measures of family expenditures (as opposed to income), which is not as frequently collected in many countries (although the U.S. has an annual expenditure survey). 59 Interestingly, the Economic Report of the President (CEA 2014) suggests that the SPM shows similar trends to an expenditure-based measure.60

A final alternative is to measure material hardship directly, rather than to assume that it is created by low income levels. Material hardship measures are only imperfectly correlated with income and clearly provide additional information about economic need.61 This approach has been adopted by the EU, which supplements a poverty measure with multiple other measures of deprivation. The EU currently requires each member state to report on 14 indicators of social exclusion, including a relative poverty measure, labor market, child well-being, and health outcomes.62

IV. THE SIZE AND COMPOSITION OF THE POOR POPULATION OVER 50 YEARS

In this section, we begin with a current snapshot of the poor population in the U.S. (including those in deep poverty), using both the official poverty measure and the SPM, shown in Figure 1. We then show the progress that the nation has made in confronting the poverty problem, relying on trends in these two measures of poverty. Finally, we show how the poverty rates of various groups have changed since the beginning of the War on Poverty.

A. Poverty in the United States in 2012: A Snapshot

Table 2 (column 1) shows the official poverty rates in 2012 for the entire population and for subgroups.63 While the official poverty rate was 15 percent, nearly 22 percent of children were poor; only 9.1 percent those aged 65 years and older were poor.

Table 2.

U.S. Poverty in 2012

| Percent Poor (official) | Percent Poor (SPM) | Percent of Poor (official) | Percent of Poor in Deep Poverty (official) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 15.0 | 16.0 | 43.7 | |

| Age group | ||||

| Children | 21.8 | 18.1 | 34.7 | 44.3 |

| Ages 18–64 | 13.7 | 15.5 | 56.9 | 45.5 |

| Age 65+ | 9.1 | 14.8 | 8.4 | 29.8 |

| All Younger than 65 | ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 10.3 | 10.4 | 40.7 | 46.6 |

| Black | 28.0 | 25.9 | 23.2 | 47.7 |

| Hispanic | 25.9 | 27.7 | 31.8 | 39.9 |

| Other | 11.6 | 16.3 | 4.3 | 53.3 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 14.2 | 15.5 | 15.7 | 45.1 |

| Midwest | 14.5 | 12.8 | 19.2 | 45.5 |

| South | 17.5 | 16.5 | 41.1 | 45.2 |

| West | 15.9 | 19.1 | 24.0 | 44.8 |

| Urban status | ||||

| Central city | 20.9 | 22.5 | 36.6 | 45.9 |

| Other metro | 11.5 | 13.4 | 31.2 | 44.8 |

| Rural | 19.4 | 14.2 | 17.5 | 43.9 |

| Unclassified | 16.1 | 14.1 | 14.7 | 45.2 |

| Family | ||||

| Nonfamily | 24.0 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 55.2 |

| Family | 14.4 | 14.9 | 75.8 | 41.9 |

| Family type | ||||

| Married-couple family | 8.0 | 10.0 | 30.9 | 34.5 |

| Male-headed family | 18.5 | 20.9 | 6.4 | 40.8 |

| Female-headed family | 35.8 | 30.7 | 38.4 | 48.1 |

| Male (nonfamily) | 21.2 | 22.5 | 11.8 | 55.7 |

| Female (nonfamily) | 27.3 | 23.0 | 12.4 | 54.9 |

| Family size | ||||

| One | 24.0 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 55.2 |

| Two | 11.6 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 45.0 |

| Three | 13.2 | 15.4 | 16.2 | 45.1 |

| Four | 12.2 | 12.6 | 17.4 | 41.8 |

| Five | 16.6 | 15.7 | 13.3 | 38.1 |

| Six or more | 25.0 | 22.1 | 14.6 | 39.0 |

| Education level of primary person | ||||

| Less than high school | 40.8 | 37.9 | 30.6 | 44.3 |

| High school | 20.0 | 19.8 | 34.6 | 44.8 |

| Some college | 14.6 | 14.3 | 25.5 | 45.3 |

| College degree | 4.8 | 6.1 | 9.4 | 53.2 |

| Work status of primary person | ||||

| Not working | 51.5 | 46.3 | 48.8 | 62.1 |

| Working less than FTFY | 27.8 | 25.9 | 32.7 | 37.6 |

| Working, FTFY | 4.6 | 6.2 | 18.5 | 16.5 |

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations.

Table 2 also presents subgroup poverty estimates for the non-elderly population. Poverty rates among non-elderly blacks and Hispanics are dramatically higher than among whites or other races. Poverty rates in the South and West are several percentage points higher than poverty rates in the Midwest and Northeast; the prevalence of poverty in central city and rural areas exceeds those in other areas. Similarly, the poverty rate among individuals who live in families is nearly 10 percentage points below that for single individuals living alone (or with other non-related people), and the poverty rate among members of married-couple families (8 percent) is very low relative to families headed by either non-married women (36 percent) or non-married men (19 percent). Those in large families are at higher risk of poverty relative to individuals in smaller families

The education of the family head is closely related to the risk of poverty. The incidence of poverty among individuals in families headed by a person with less than a high school diploma is more than 40 percent, compared to a less than 5 percent chance among individuals in families headed by a college graduate. Employment also matters; the poverty rate among individuals in families in which the head is not working is 51 percent; by comparison, if the family head works full time the poverty rate is less than 5 percent.

Poverty rates based on the SPM are shown in the second column of Table 2. In 2012, the SPM poverty rate—16 percent—is only one point higher than the official poverty rate. However, the two measures vary significantly across subgroups of the population. For example, the SPM rate for the elderly is nearly 6 percentage points higher than the official rate, largely reflecting the large out-of-pocket medical expenses that are counted against income in the SPM.64 Similarly, the higher SPM poverty rates for those living in the West reflect high shelter costs in this region. The SPM results in lower rates of rural poverty relative to the official measure largely because shelter cost adjustments result in lower SPM thresholds in rural areas. SPM poverty rates for children and female-headed families are lower than official poverty rates, largely because tax subsidies (e.g., the EITC) and in-kind transfers (e.g., SNAP benefits) vary with family size and are taken into account in the SPM. Females that are not members of a family have much lower SPM poverty rates, largely due to their cohabiting living situation (which is recognized by the SPM but not the official measure).

B. The Composition of the Poor

The third column in Table 2 provides information on the composition of the officially defined non-elderly poor in 2012. Subgroups can make up a large percentage of the poor because they have high poverty rates, because they have high population shares, or because they have both high poverty rates and high population shares. Subgroups that compose a large fraction of the poor due primarily to high poverty rates include blacks, Hispanics, single/cohabiting people (particularly women), those in families in which the head has less than a high school degree, and individuals in families in which the head is working less than full time, year round.65

In contrast, other groups (e.g., prime-aged adults, whites, married-couple families, those living in families in which the head has some college or is working full time, full year) represent a substantial percentage of the poor primarily because these groups are relatively large shares of the overall population. For example, the poverty rate among individuals in married couple families is only 8 percent, but because individuals in these families make up 60 percent of the overall population, they account for 30 percent of the poor.

Finally, children, those living in the South, in central cities, and in families with a head that has a high school diploma (but no college) constitute a large fraction of the poor both because of high poverty rates and high population shares. For example, the high 22 percent poverty rate among children, along with the fact that they compose nearly 24 percent of the population, account for children being more than one-third of all poor people in the U.S.

C. Deep Poverty

The final column of Table 2 shows the fraction of the official poor that are living in deep poverty—those in families with pre-tax cash income of less than 50 percent of the official poverty threshold. Deep poverty is of particular concern because of its links to material hardship and negative outcomes among children (Shaefer & Edin, 2013; Iceland & Bauman, 2007; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997).

Overall, 44 percent of the poor are classified as being in deep poverty. Across age groups 44 percent to 46 percent of poor children and adults ages 18 to 65 are in deep poverty, compared with only 30 percent of poor adults ages 65 and older. The high child poverty rate (22 percent), coupled with the fact that an estimated 44 percent of poor children live in deep poverty, means that about 10 percent of all American children live in families with cash income below one-half of the poverty line; this is a pattern of great concern.66 While between 44 percent and 48 percent of the non-elderly poor in most of the subgroups are in deep poverty, there are some notable exceptions. Hispanics have a high rate of poverty but, relative to blacks and whites, a low rate of deep poverty. People living alone or with unrelated adults have both a high incidence of poverty and an exceptionally high incidence of deep poverty (55 percent). Another group for which deep poverty is clearly a concern is families in which the head is not working. Over 50 percent of individuals in these families are poor and 62 percent of them are in deep poverty.

Measurement matters a great deal in determining the extent of deep poverty in the U.S. Differences in deep poverty rates between the official and SPM are dramatic. In spite of the SPM poverty rate exceeding the official rate, there is a lower fraction of the poor in SPM deep poverty. This is largely because the SPM includes measures of in-kind benefits that the very poor are likely to receive. These differences between SPM and official measure of deep poverty are apparent for all subgroups with the exception of the elderly, individuals in a family unit headed by a college graduate, and individuals in a family unit in which the head is working full time and full year.

D. Trends in Poverty

How much progress has been made toward alleviating poverty since the War on Poverty was begun 50 years ago?

As noted above, Figure 1 plots the official and SPM poverty measures.67 The SPM falls more rapidly over the late 1960s and 1970s, as Food Stamps and housing assistance programs are being implemented and expanded. The SPM also falls more rapidly in the early 1990s, when the EITC is being expanded. Both measures show poverty trending up since 2000, although the official poverty measure shows a much bigger jump in poverty during the Great Recession. Over the entire period for which the official and SPM poverty rates are available, the two measures lead to different conclusions about progress on alleviating poverty; while the SPM indicates a downward trend, and the official measure shows virtually no long-term trend. As the SPM and official thresholds are historically very close (Fox et al., 2014), differences in the trends are primarily due to differences in counted resources and, to a lesser extent, different definitions of the resource-sharing unit.68

In the 10 years after President Lyndon Johnson's famous State of the Union address calling for a “War on Poverty,” the official poverty rate declined rapidly from 19 percent in 1964 to 11.1 percent in 1973. Over the entire period since the start of the War, the poverty rate has never been lower than it was in 1973. Between 1974 and 1979 the poverty rate remained below 13 percent despite the turbulent stagflation during this period.

Although the 1980s economic recovery was pronounced in terms of the GDP growth and the decline in overall unemployment, increases in earnings and income were distributed to those nearer to the top of the income distribution. As a result, neither poverty rate declined during this period by as much as might have been anticipated on the basis of earlier periods of economic recovery.69

The early 1990s saw another recession followed by a prolonged recovery. Unlike the recovery in the 1980s, this recovery led to wage gains, employment gains, and increases in the labor force participation rate of workers at the bottom of the wage distribution. These gains are reflected in the poverty rates with the official rate hitting a 20-year low of about 11 percent in 2000. Before the 1990s the SPM poverty rate was roughly between one and two percentage points higher than the official poverty rate. This difference reflected the burden of federal, state, and payroll taxes on the poor. Due to expansions of the EITC beginning in 1986, reductions in payroll tax rates that began several years earlier and continued through the late 1980s, and changes in state-level tax policies, the tax burden on the poor decreased significantly in the 1990s.70 All of these factors are reflected in the more rapid decline of the SPM in the 1990s.

The recession of the early 2000s pushed the official poverty rate up to about 13 percent in 2004. Although the rate fell slightly by 2006, the end of 2007 marked the beginning of the Great Recession. In response, the poverty rate increased to over 15 percent in 2010, where it has remained since.

Particularly interesting is a comparison of the SPM versus the official poverty measure during the recent recession. During the recession, recipients of Unemployment Insurance retained benefits far longer than the typical 6-month period, increasing cash income. The official poverty measure, which reflects changes in pretax cash income, shows the poverty rate rising by slightly less than 2 percentage points between 2008 and 2010. This increase is surprisingly low based on the historical relationship between changes in the unemployment rate and changes in the poverty rate. The SPM shows even less of a rise in poverty, since it also measures the impact of increased eligibility for Food Stamps and for EITC payments as family income falls due to rising unemployment. In the SPM, poverty rises less than 1 percentage point from 2008 to 2010, to 15.3 percent.71

E. Subgroup Trends in Poverty

Table 3 shows official poverty rates for demographic subgroups in 1968, 1990, 2006, and 2012 (unfortunately, SPM poverty rates for subgroups are not available going as far back as 1968). With the exception of 2012, the years shown in Table 3 reflect relatively low points in the national unemployment rate. As with the poverty rates shown in Table 2, in Table 3 the poverty rate of individuals over the age of 65 is omitted from subgroups. In examining Table 3 a few patterns stand out.

Table 3.

Poverty Rates By Year (Official Measure)

| Year |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | 1990 | 2006 | 2012 | |

| All | 12.8 | 13.5 | 12.3 | 15.0 |

| Age group | ||||

| Children | 15.4 | 20.6 | 17.4 | 21.8 |

| Age 18-64 | 9.0 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 13.7 |

| Age 65+ | 25.0 | 12.1 | 9.4 | 9.1 |

| All Younger than 65 | ||||

| Racea | ||||

| White | 7.5 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 10.3 |

| Black | 32.8 | 31.6 | 24.2 | 28.0 |

| Hispanic | 23.8 | 28.3 | 20.7 | 25.9 |

| Other | 15.1 | 14.9 | 9.9 | 11.6 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 8.0 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 14.2 |

| Midwest | 8.1 | 12.5 | 11.7 | 14.5 |

| South | 18.9 | 15.7 | 14.1 | 17.5 |

| West | 9.3 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 15.9 |

| Urban status | ||||

| Central city | 12.2 | 20.0 | 16.7 | 20.9 |

| Other metro | 6.4 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 11.5 |

| Rural | 16.3 | 16.4 | 15.9 | 19.4 |

| Unclassified | na | 13.2 | 12.5 | 16.1 |

| Family | ||||

| Nonfamily | 24.3 | 18.8 | 20.8 | 24.0 |

| Family | 10.9 | 13.0 | 11.3 | 14.4 |

| Family type | ||||

| Married-couple family | 7.6 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 8.0 |

| Male-headed family | 16.7 | 12.4 | 14.7 | 18.5 |

| Female-headed family | 40.6 | 39.4 | 31.9 | 35.8 |

| Male (nonfamily) | 18.8 | 16.4 | 18.4 | 21.2 |

| Female (nonfamily) | 28.9 | 21.9 | 23.7 | 27.3 |

| Family size | ||||

| One | 24.3 | 18.8 | 20.8 | 24.0 |

| Two | 8.3 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 11.6 |

| Three | 6.8 | 11.8 | 10.8 | 13.2 |

| Four | 7.1 | 10.9 | 9.8 | 12.2 |

| Five | 9.4 | 14.7 | 12.0 | 16.6 |

| Six or more | 19.2 | 24.2 | 19.3 | 25.0 |

| Education level of primary person | ||||

| Less than high school | 19.5 | 33.3 | 31.4 | 40.8 |

| High school | 6.8 | 13.3 | 14.8 | 20.0 |

| Some college | 5.5 | 8.8 | 10.6 | 14.6 |

| College degree | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 4.8 |

| Work status of primary person | ||||

| Not working | 42.9 | 55.5 | 47.2 | 51.5 |

| Working less than FTFY | 22.0 | 25.4 | 24.3 | 27.8 |

| Working, FTFY | 5.4 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.6 |

First, there has been no apparent progress in alleviating childhood poverty. In 1968, 15.4 percent of children were poor, which is lower than the rate of poverty among children in 1990, 2006, and 2012, the first two reflecting periods of relative economic prosperity. A large part of the reason that the poverty rate among children has remained stubbornly high is the increased prevalence of female-headed families. While the poverty rate for female-headed families has decreased since 1968, it remains high relative to other family types, and the share of children living in such families increased markedly—from 12 percent in 1968 to 27 percent in 2012. Had the distribution of children between married-couple, male-headed, and female-headed families remained as it was in 1968, the child poverty rates in 1990, 2006, and 2012 would have been 15.4 percent, 14 percent, and 15.5 percent, respectively—all considerably lower than the rates shown in Table 3.72

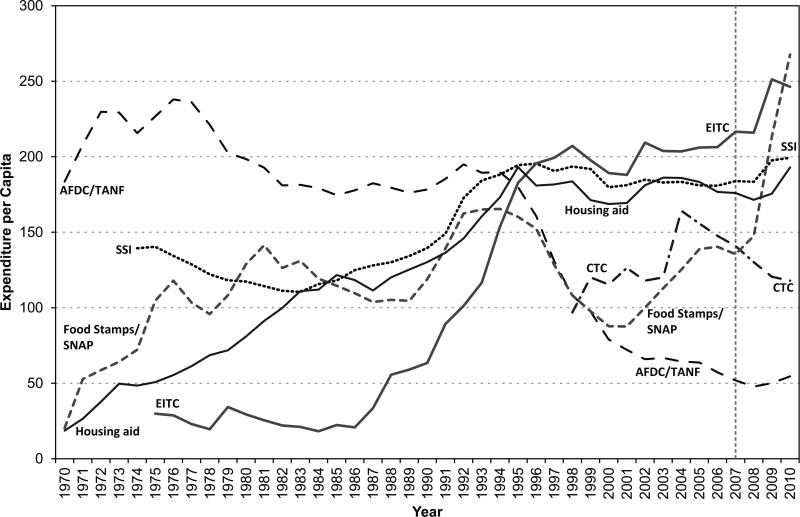

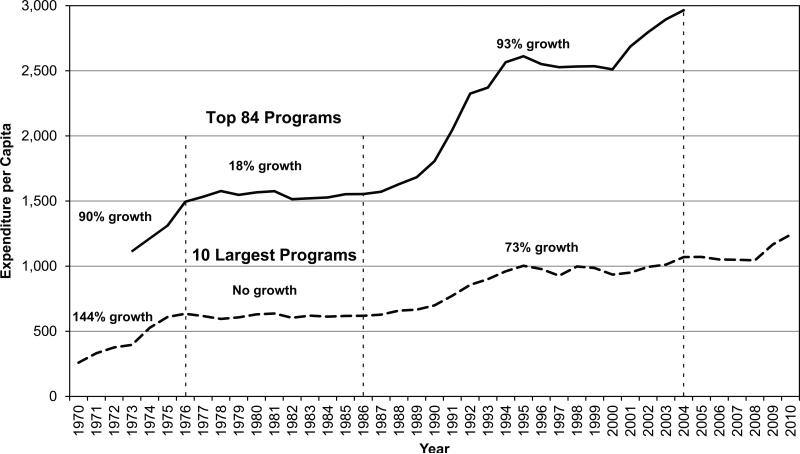

A second factor contributing to high poverty rates among children has to do with poverty measurement and the movement away from cash-based assistance and toward tax credits and in-kind benefits. Simply put, the non-medical means-tested programs that have expanded most rapidly since 1970 are targeted at families with children. As we show in the following section, these programs now account for the highest per-capita expenditures among means-tested programs (see Figure 3); however, they do not reduce official poverty directly because the benefits are not counted as resources in the official poverty measure. Using the official threshold, and counting just SNAP benefits and net tax liability as resources, reduces the 2012 child poverty rate to its 1968 levels and reduces the 2006 child poverty rate to below 14 percent. This result is consistent with Fox et al. (2014), who show the SPM poverty rate among children falling between 1967 and 2012 largely due to increases in in-kind transfers that are not valued as resources under the official poverty measure. Our own calculations indicate that using the official thresholds, counting Food Stamp benefits and EITC benefits as resources, and fixing the distribution of children between married-couple, male-headed, and female-headed families at 1968 levels, would reduce the 2012 child poverty rate by half.

Figure 3. Expenditure per Capita, Non-Medicaid Means-Tested Programs, 1970–2010 (real 2009 dollars).

Sources: Various governmental and administrative data series available from the authors upon request.

Note: The U.S. population data are from the “Civilian noninstitutional population” column of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey” table (see http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat01.htm), and they include everyone in that population, including children.

The second pattern that stands out from Table 3 is the sharp increase in the poverty rate among people living in families in which the head has less than a college degree, particularly between 1968 and 1990. These trends reflect economic and institutional changes that have led to declining wages and employment among less-skilled workers, including the decline in the real value of the minimum wage (DiNardo, Fortin, & Lemieux, 1996; Lee, 1999; Card & DiNardo, 2002); skill-bias in technological change (Katz & Murphy, 1992; Autor, Levy, & Murnane, 2003; Autor, Katz, & Kearney, 2008); and the decline in unionization (DiNardo, Fortin, & Lemieux, 1996; Card, 1996).

Third, there have been declines in the incidence of poverty among blacks ages 18 to 64, particularly over the 1970 to 2006 period. For blacks, the poverty rate decreased by about 25 percent over this period from over 32 percent in 1970 to about 24 percent in 2006. 73 The black poverty rate did not decrease at a constant rate throughout this period. Between 1970 and 1979 the black poverty rate decreased by about 4 percentage points followed by an increase of roughly 2.5 percentage points between 1979 and 1992. During the middle- and late-1990s the black poverty rate dropped rapidly, reaching a historic low of 21.8 percent in 2000. Between 2000 and 2006 it increased steadily to 24 percent. Although the poverty rate among blacks increased during the Great Recession, these increases largely mirror those of other traditionally disadvantaged groups with high poverty rates.

One factor that is worth considering when evaluating progress on reducing black poverty is the impact of mass incarceration, which has disproportionately affected black men. There is emerging evidence that the poverty rate may be substantially elevated due to the impact of mass incarceration (Defina & Hannon, 2010, 2013). Incarceration can affect poverty by directly removing persons from the population considered for the purpose of calculating poverty rates and into the institutional population, or by altering the future labor market prospects of incarcerated individuals and the social capital of their communities. Defina and Hannon (2013) estimate that in absence of the upward trend in incarceration, the poverty rate would have decreased by 20 percent between 1980 and 2004, a period over which the poverty rate actually increased. While they do not conduct estimates on subgroups, given the disproportionate increase in incarceration rates among blacks, it seems likely that this effect would be concentrated on black poverty.