Abstract

Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) have developed a grounded approach to conducting practice-relevant and translational research in community practice settings. Seismic shifts in the healthcare landscape are shaping PBRNs that work across organizational and institutional margins to address complex problems. Praxis-based research networks combine PBRN knowledge generation with multi-stakeholder learning, experimentation, and practical knowledge application. The catalytic processes in praxis-based research networks are cycles of action and reflection based on experience, observation, conceptualization, and experimentation by network members and partners. To facilitate co-learning and solution-building, these networks have a flexible architecture that allows pragmatic inclusion of stakeholders based on demands of the problem and the needs of the network. Praxis-based research networks represent an evolving trend that combines the core values of PBRNs with new opportunities for relevance, rigor, and broad participation.

Introduction

For more than 30 years, PBRNs have engaged clinicians in investigating questions to improve the quality of primary care(1). This work initially involved the development of guiding principles and supporting infrastructure to provide ‘laboratories’ for primary care research(2). As an extension of translational research, many networks have integrated quality improvement initiatives into their work, suggesting that PBRNs have the potential to become learning communities(3). Increasingly, research opportunities for PBRNs lie beyond the boundaries of practices and healthcare systems. Although increasing numbers of networks are conducting research on a broader scale(4–7) many PBRNs lack the infrastructure and expertise to do so. The purposes of this manuscript are to present the benefits and challenges encountered when PBRNs directly partner with diverse organizations including public health departments, schools, patient advocacy groups, and non-profit social service organizations, and to propose an approach to building research partnerships across organizational and institutional boundaries.

Environmental Shifts and New Opportunities

Unsustainable healthcare spending and unacceptable population health outcomes have spawned initiatives to transform the complex U.S. healthcare system,(8–12) and PBRNs are challenged to configure themselves to effectively respond to resulting new opportunities. Although there are significant benefits to a population-based approach to primary care, the predominant fee-for-service payment model in the U.S. has not supported the development of an integrated primary care-public health system(13–16) To address this issue, provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 are enabling the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to fund initiatives that bridge this longstanding separation.(10, 17–19) Further, approaches to the integration of primary care, public health, and communities put forth in the 1967 Folsom Report(20) are being revisited(21) for their potential to address this division by embracing the community-oriented primary care model pioneered by Kark in the 1940s.(15, 20–22)

Numerous research opportunities for PBRNs are resulting from these developments. The emergence of Accountable Care Organizations provides opportunities to partner with healthcare systems and communities to work toward achieving the ‘triple aim’ of improving the patient’s experience of healthcare, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita healthcare cost.(23, 24) The development of the Patient Centered Medical Home offers abundant opportunities for PBRNs to study and improve practice organizational factors, efficiency, patient satisfaction, and population health outcomes.(25, 26) The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is supporting patient- and community-guided projects that enable patients to make better informed healthcare decisions based on high quality evidence, and offers opportunities for PBRNs to link practices, patients, and communities for patient-centered research that improves health outcomes.(27, 28)

Broadening the Paradigm

“ We are not students of some subject matter, but students of problems. And problems may cut right across the borders of any subject matter or discipline.”

—Karl Popper

Each of the opportunities described above sits at the margins of various stakeholder groups and institutions where innovative solutions to complex problems can be developed.(29–33) These opportunities beckon PBRNs to embrace the broader mission of improving the health of communities as they “investigate questions related to community-practice and improve the quality of primary care,” as described in the definition of a PBRN by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.(34)

To capitalize on opportunities to address ‘wicked’ health problems that often defy linear solutions,(35, 36) PBRNs face the challenge of maintaining their strengths in practice-based research methods and implementation while developing the capacity to partner and innovate across the interfaces of primary care, public health, healthcare systems, patient groups, community agencies, business communities, and universities.(37) Although PBRNs operate in the space that touches many of these groups, organizations, and institutions, networks may lack experience in working across the margins.

Successful boundary spanning is taking place within PBRNs, however. PBRN-initiated partnerships to create ‘communities of solution’(21) using community-based participatory research methods have been described,(37, 38) and a growing number of PBRNs are partnering across boundaries to address complex health issues.(6, 39)

For example, the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) is engaged in developing a primary care extension program to link primary care practices, public health departments, and academic centers to provide technical assistance, training, practice facilitation, and resources to address priority health needs and the social determinants of health.(40) At the county level, the extension program’s health improvement organizations are collaboratives of non-profit service organizations that connect primary care clinics to social services, public health departments, schools, tribes, hospitals, and mental health resources.(41)

In the Research Involving Outpatient Settings Network (RIOS Net), patients were recruited from diverse communities across New Mexico to participate in a study of community-level perceptions of low-risk health research, human research protection processes, and the ethical conduct of community-based research.(42) In collaboration with the PRIMENet PBRN collaborative, the network also conducted a project to identify strategies for successfully recruiting and retaining members of diverse racial/ethnic communities into PBRN research studies.(43)

In southern California, the independent non-profit PBRN L.A. Net is partnering with federally qualified health centers, schools, and community organizations to reduce health disparities. The network has engaged with community service organizations to conduct a series of studies aimed to reduce childhood aggression and violence through culturally-appropriate family-based interventions.(44, 45)

The High Plains Research Network in Colorado is guided by a patient-comprised Community Advisory Council which routinely guides the development and implementation of community-based participatory research projects. The PBRN has completed community-based studies to increase rates of health screening and improve chronic disease self-management. Effective local messages to promote screening for colon cancer and self-management of asthma and hypertension were collaboratively developed by more than 1000 patients and clinicians using a method developed by the PBRN known as ‘boot camp translation.’(37, 46, 47) These highly collaborative, boundary spanning, community-oriented PBRNs are showing the way to a broad and inclusive PBRN model that may presage the future of practice-based research.

Re-conceptualizing PBRNs

“Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.”

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

In light of the sweeping changes to our healthcare system, the corresponding research opportunities that favor community and cross-organizational partnerships, and the shifts in PBRNs toward the direct engagement of communities and diverse organizational partners, it may be useful to broadly conceptualize the practice-based research network as a multi-stakeholder learning organization that seeks to improve community health. This is being achieved by PBRNs through mutually-beneficial partnerships for research, healthcare improvement, knowledge application, and learning. The role of community healthcare practices and clinicians as core PBRN stakeholders remains unchanged as networks flexibly engage and partner with relevant groups and organizations to improve the health of communities. By adaptively responding to opportunities in their environments, these networks have evolved the PBRN model from a practice-focused research organization to one that is significantly more broad and inclusive. Less clear are processes through which these networks can effectively create bridges and partner in pragmatic and creative ways to impact population health.

The term praxis-based research network is proposed as a name for the expanded PBRN model described here. The word ‘praxis’ refers to pragmatically applying knowledge and theory, interpreting the meaning of experience, reframing problems in light of experience, and applying new solutions. Praxis takes the form of experiential learning, an evidence-based learning model that is widely used in research and education.(48, 49) We propose that experiential learning is the central process by which PBRNs can develop cross-boundary partnerships that are productive, sustainable, and mutually rewarding.

Methods for Addressing Challenges

“Experience is the teacher of all things.”

—Julius Caesar

Limitations in developing partnerships across boundaries involve two major challenges that can be met by praxis-based research networks: developing an evolving co-learning process that bridges organizational gaps and meets both the short- and long-term needs of partnering organizations, and flexibly partnering to address the complex problems that cut across boundaries while maintaining integrity as a cohesive network.

Developing a co-learning process requires a flexible approach that rewards the return on investment for both the network and the partnering organization in the short- and long-term. Long-range objectives for PBRN partnerships include obtaining grant funding, completing research studies and quality improvement initiatives, and disseminating research findings. Grants proposals may have a relatively low probability of being funded and dissemination activities often take place only after years of project development and data collection. Due to the length of time for achievement and low frequency of occurrence, the pursuit of high stakes objectives alone may fail to sustain boundary spanning partnerships over time. In developing partnerships, overreliance on ‘hitting the home run’ can unnecessarily limit shared learning that can lead to practical short term benefits and the identification of promising long range opportunities.

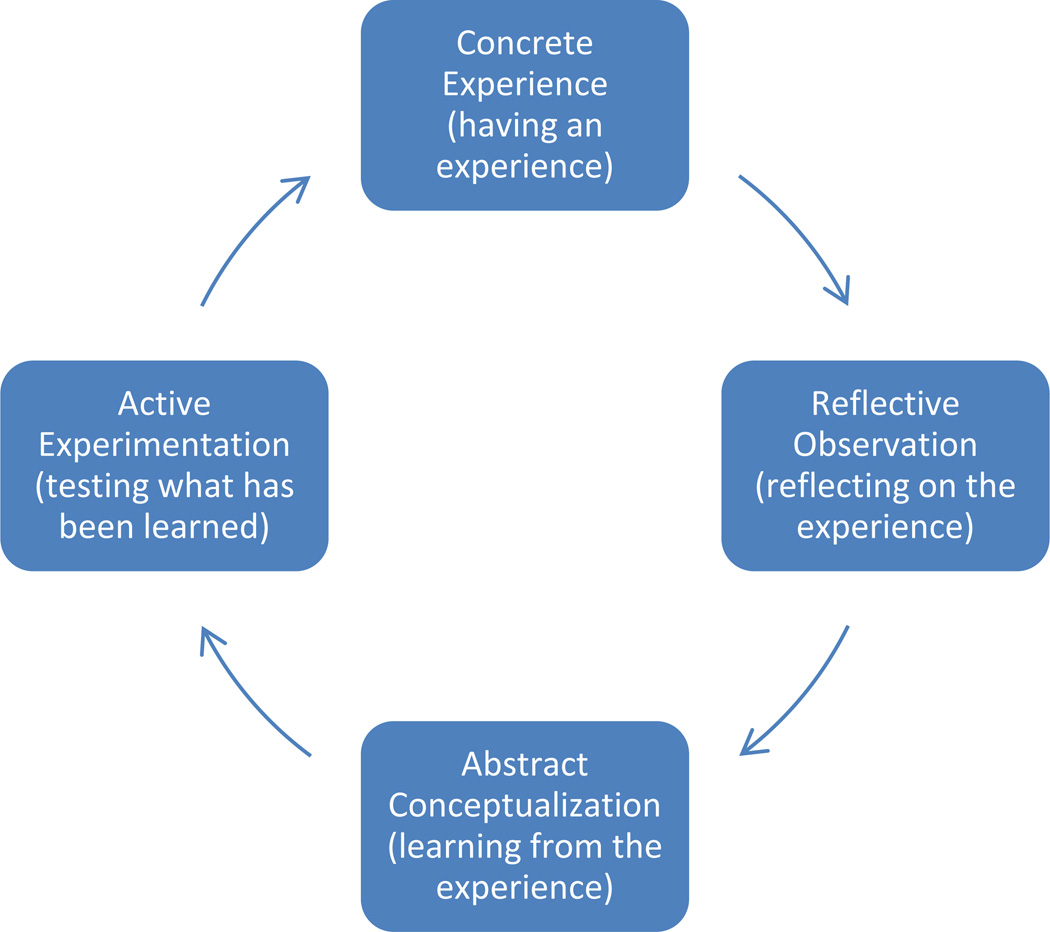

To address this challenge, praxis-based research networks can use the experiential learning cycle(48) to enhance partnerships and create opportunities. As shown in Figure 1, experiential learning consists of experience, reflective observation, conceptualization, and experimentation. Using this model, partners interact around issues and activities relevant to the goals of the partnership. They observe and reflect on what has been learned during the experiential action phase, interpret the information from their distinct perspectives, and conceptualize how this can lead to short- and long-term solutions and collaborative opportunities. Partnering organizations that share their experiences benefit from the short-term solutions generated in the reflective observation and conceptualization phases, and all parties benefit by identifying research and QI opportunities that increase the long-term value of the partnership.

Figure 1. The Experiential Learning Cycle.

Source: Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Praxis-based research networks can meet the challenge of creating adequate breadth to address problems that cut across boundaries by having selectively permeable network borders based on priorities and opportunities. Adequate organizational and conceptual space is needed to selectively include new stakeholders from diverse groups, with the understanding that the network and its collaborations will expand and contract as partnerships ebb and flow based on resources and shared opportunities. This flexible architecture will allow networks to rapidly shift in response to opportunities for beneficial partnerships.

Organizational identity is particularly relevant to developing the flexibility to partner effectively. To maintain their organizational identity in partnerships, evolving PBRNs seek not just to maintain systems, processes, and strategies but to develop their organization’s core values over time.(50) In the context of environmental changes, PBRNs may in fact find that partnerships enable their organization’s core values to be sustained(51) as the network continues to evolve. Finally, the choice of partnering organizations can be guided by the potential value of the outcomes the partners can achieve together. Pragmatic inclusiveness when partnering across the margins opens doors to countless possibilities for networks.

PBRNs are likely to benefit from an examination of their capacities for partnering. As smaller organizations, PBRNs often have a predominant informal organizational structure in which the pragmatics of getting the work done supersedes the need for hierarchy, whereas larger organizations and governmental agencies may adhere to a more formal structure involving chains of command and procedural control. This mismatch can create problems in partnering if assumptions about collaborations are not made explicit.(50) Additional factors shown to affect the viability of partnerships include mutual trust, flexibility in dealing with one another, understanding organizational cultures, sharing power, having a shared mission, friendship, open communication and information sharing, and mutual commitment to the project.(52) PBRNs can weigh these factors by engaging in a thorough self-evaluation and an assessment of the prospective partnering organization.

Accessing Resources

PBRNs may require training and assistance in spanning institutional boundaries and engaging community groups. Institutions awarded one of the 61 NIH-funded Clinical and Translational Science Awards are likely to support community research partnership shared resources that have expertise in research methods for community engagement. These shared resources may offer training in community-based research methods and provide linkages to community organizations. The Clinical and Translational Science Institute at the University of California, San Francisco offers a series of online training manuals in community engaged research (http://accelerate.ucsf.edu/research/community-manuals). Similarly, the 37 CDC-funded Prevention Research Centers across the U.S. have expertise in community engaged research methods and may offer training and technical assistance. In addition, the PBRN Resource Center offers learning groups, webinars, and tool kits on a variety of important topics relevant to PBRNs (http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/resource-center). Finally, networks often learn best from one another. PBRNs that have pioneered community engaged research may serve as exemplars in collaborating across boundaries.

Conclusion

Even as changes within the U.S. health care system and the nation’s research funding infrastructure create challenges for PBRNs, participatory collaborations are creating new opportunities. In response to changing environments, PBRNs are dynamically evolving to meet the needs of communities by partnering to generate new knowledge that can benefit community and population health. The praxis-based research network model facilitates adaptive partnering and provides a learning mechanism that enables the formation of new collaborations while remaining true to the core values of PBRNs.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This publication was made possible by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and by the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant, P30 CA-43703-23 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stange’s time is supported in part by a Clinical Research Professorship from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Competing interests or conflicts of interest: Neither author has any competing interests or conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

James J. Werner, Family Medicine and Community Health, Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cleveland Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, OH 44106-7136.

Kurt C. Stange, American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor, Professor of Family Medicine & Community Health, Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Oncology and Sociology, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, OH 44106-7136.

References

- 1.Green LA, Hickner J. A short history of primary care practice-based research networks: from concept to essential research laboratories. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green LA, White LL, Barry HC, E D, Hudson BL. Infrastructure Requirements for Practice-Based Research Networks. 2005;3(suppl_1):S5–S11. doi: 10.1370/afm.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary Care Practice-Based Research Networks: Working at the Interface Between Research and Quality Improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl_1):S12–S20. doi: 10.1370/afm.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macaulay AC, Nutting PA. Moving the frontiers forward: incorporating community-based participatory research into practice based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2006 doi: 10.1370/afm.509. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westfall JM, Fagnan LJ, Handley M, Salsberg J, McGinnis P, Zittleman LK, et al. Practice-based research is community engagement. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(4):423–427. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westfall JM, VanVorst RF, Main DS, Herbert C. Community-based participatory research in practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(1):8–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams RL, Shelley BM, Sussman AL. The marriage of community-based participatory research and practice-based research networks: can it work? -A Research Involving Outpatient Settings Network (RIOS Net) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(4):428–435. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.090060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keehan SP, Sisko AM, Truffer CJ, Poisal JA, Cuckler GA, Madison AJ, et al. National health spending projections through 2020: economic recovery and reform drive faster spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(8):1594–1605. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better--improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IOM, (Institute of Medicine) Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IOM, (Institute of Medicine) For the Public's Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IOM, (Institute of Medicine) Population Health Implications of the Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The rise of a sovereign profession and the making of a vast industry. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullan F, Epstein L. Community-oriented primary care: new relevance in a changing world. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1748–1755. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longlett SK, Kruse JE, Wesley RM. Community-oriented primary care: historical perspective. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(1):54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scutchfield FD, Michener JL, Thacker SB. Are we there yet? Seizing the moment to integrate medicine and public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 3):S312–S316. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. n.d.;Pages http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/law/ on July 2, 2014.

- 19.Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NCCHS. Health is a Community Affair—Report of the National Commission on Community Health Services (NCCHS) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Folsom Group. Communities of solution: the Folsom Report revisited. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(3):250–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kark SL. The Practice of Community-Oriented Primary Healthcare. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Croft; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berenson RA, Burton RA. Washington DC: Urban Institute; 2011. Accountable care organizations in Medicare and the private sector: a status update [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009;301(19):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krumholz HM, Selby JV. Seeing through the eyes of patients: the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Funding Announcements. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):446–447. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mittelstrauss J. On transdisciplinarity. TRAMES. 2011;15(4):329–338. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ernst C, Chrobot-Mason D. Boundary Spanning Leadership. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams P. The life and times of the boundary spanner. Journal of Integrated Care. 2011;19(3):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.PHAB Staff and Writing Committee. Aungst H, Ruhe M, Stange KC, PHAB Cleveland Advisory Committee. Allan TM, et al. Boundary spanning and health: invitation to a learning community. London Journal of Primary Care. 2012;4(2):109–115. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2012.11493346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stange KC. Refocusing knowledge generation, application and education: Raising our gaze to promote health across boundaries. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S164–S169. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Pages http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/faqs#PBRN on July 1, 2014.

- 35.Blackman T, Greene A, Hunter DJ, McKee L, Elliott E, Harrington B, et al. Performance assessment and wicked problems: the case of health inequalities. Public Policy and Administration. 2006;21:66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Signal LN, Walton MD, Ni Mhurchu C, Maddison R, Bowers SG, Carter KN, et al. Tackling 'wicked' health promotion problems: a New Zealand case study. Health Promot Int. 2013;28(1):84–94. doi: 10.1093/heapro/das006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norman N, Bennett C, Cowart S, Felzien M, Flores M, Flores R, et al. Boot camp translation: a method for building a community of solution. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(3):254–263. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griswold KS, Lesko SE, Westfall JM. Communities of solution: partnerships for population health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(3):232–238. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.130102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westfall JM, Dolor RJ, Mold JW, Hedgecock J. PBRNS engaging the community to integrate primary care and public health. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):284–285. doi: 10.1370/afm.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Health Extension Toolkit. Pages http://healthextensiontoolkit.org/about/participating-states/lead-state/oklahoma/ on July 6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Health Extension: Role in Primary Care & Community Health. Pages http://hsc.unm.edu/community/toolkit/docs9/HealthExtensionToolkitWebinar.pdf on July 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams RL, Willging CE, Quintero G, Kalishman S, Sussman AL, Freeman WL, et al. Ethics of health research in communities: perspectives from the southwestern United States. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(5):433–439. doi: 10.1370/afm.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Getrich CM, Sussman AL, Campbell-Voytal K, Tsoh JY, Williams RL, Brown AE, et al. Cultivating a cycle of trust with diverse communities in practice-based research: a report from PRIME Net. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):550–558. doi: 10.1370/afm.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson AA, Knox L, Guerra NG, Williams KR. A pilot randomized trial of community-based parent training for immigrant Latina mothers. Am J Community Psychol. 2014;53(1–2):47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knox L, Guerra NG, Williams KR, Toro R. Preventing children's aggression in immigrant Latino families: a mixed methods evaluation of the Families and Schools Together program. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;48(1–2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zittleman L, Emsermann C, Dickinson M, Norman N, Winkelman K, Linn G, et al. Increasing colon cancer testing in rural Colorado: evaluation of the exposure to a community-based awareness campaign. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norman N, Cowart S, Felzien M, Haynes C, Hernandez M, Rodriquez MP, et al. Testing to prevent colon cancer: how rural community members took on a community-based intervention. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):568–570. doi: 10.1370/afm.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolb AY, Kolb DA. Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2005;4(2):193–212. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brinkerhoff JM. Government-nonprofit partnership: a defining framework. Public Administration and Development. 2002;22:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gagliardi P. The creation and change of organizational cultures: a conceptual framework. Organization Studies. 1986;7(117–134) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw MM. Successful collaboration between the nonprofit and public sectors. Nonprofit management and leadership. 2003;14(1):107–119. [Google Scholar]