Abstract

The TSH receptor (TSHR) on the surface of thyrocytes is unique among the glycoprotein hormone receptors in comprising two subunits: an extracellular A-subunit, and a largely transmembrane and cytosolic B-subunit. Unlike its ligand TSH, whose subunits are encoded by two genes, the TSHR is expressed as a single polypeptide that subsequently undergoes intramolecular cleavage into disulfide-linked subunits. Cleavage is associated with removal of a C-peptide region, a mechanism similar in some respects to insulin cleavage into disulfide linked A- and B-subunits with loss of a C-peptide region. The potential pathophysiological importance of TSHR cleavage into A- and B-subunits is that some A-subunits are shed from the cell surface. Considerable experimental evidence supports the concept that A-subunit shedding in genetically susceptible individuals is a factor contributing to the induction and/or affinity maturation of pathogenic thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies, the direct cause of Graves' disease. The noncleaving gonadotropin receptors are not associated with autoantibodies that induce a “Graves' disease of the gonads.” We also review herein current information on the location of the cleavage sites, the enzyme(s) responsible for cleavage, the mechanism by which A-subunits are shed, and the effects of cleavage on receptor signaling.

Introduction: Discovery of the TSH Receptor

Discovery of a Multisubunit TSH Receptor

Does the “Mature” TSHR Comprise Two Subunits or a Single Polypeptide?

What Is the TSH Receptor Subunit Structure on Thyrocytes in Vivo?

TSH Receptor Subunit Nomenclature

“There Is a Piece Missing in the TSHR”

-

Where Are the TSH Receptor Intramolecular Cleavage Sites?

Mutagenesis to prevent or to introduce receptor intramolecular cleavage

Estimation of the masses of A- and B-subunits formed by intramolecular cleavage

Direct amino acid sequencing of the N-termini of purified B-subunits

-

Mechanism of TSHR Intramolecular Cleavage

Cellular location of cleavage

Enzyme responsible for TSHR intramolecular cleavage

Factors influencing TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits

-

Mechanism of A-Subunit Shedding

Disulfide bond reduction by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI)

Proteolytic removal of cysteine residues in the polypeptide chain

-

Does TSHR Intramolecular Cleavage Have Functional Consequences?

TSH binding affinity

TSH activation of the TSHR

Relation between TSHR cleavage and receptor constitutive activity

“Neutral” antibodies and TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits

-

A Pathophysiological Role for TSHR A-Subunit Shedding?

Are shed TSHR A-subunits present in serum in vivo?

Can shed TSHR A-subunits in serum bind TSH?

Evidence that shed TSHR A-subunits play a role in the pathogenesis of Graves' disease

Conclusions and Phylogenetic Divergence of the TSHR From the Gonadotropin Receptors

I. Introduction: Discovery of the TSH Receptor

Evidence for the existence of a TSH receptor (TSHR), indeed of any polypeptide hormone receptor, was first presented by Pastan, Roth, and Macchia in 1966 when they concluded that “the initial interaction of polypeptide hormones with target tissue is rapid, firm binding to a superficial cell site, presumably on the external cell membrane” (1). Confirmation of this concept followed in 1973 when Amir et al (2) demonstrated specific binding of radiolabeled TSH to thyroid plasma membranes.

II. Discovery of a Multisubunit TSH Receptor

The first visualization of the TSHR was obtained by the Rees Smith laboratory in 1982, providing the seminal observation that the human and porcine receptors comprised two subunits linked by disulfide bonds, with a molecular mass of 87–100 kDa and binding one molecule of TSH (3). In a series of pioneering experiments, these investigators generated information that remains valid more than 30 years later. The ligand TSH was reported to bind to a water-soluble component of the TSHR on the cell surface attached to a membrane-associated component, which they termed A- and B-subunits, respectively (for example, see Refs. 4 and 5). At the time of these cross-linking experiments, it was unknown whether the TSHR was, like the ligand TSH, coded for by two separate genes or by a single gene whose translation product was then cleaved into A- and B-subunits. In a remarkably prescient report on the TSHR expressed on FRTL5 rat thyroid cells, the Rees Smith group proposed that the TSHR was synthesized as a single-chain precursor of 120 kDa with an intrinsic disulfide-bridged loop in the extracellular region. Subsequent “proteolytic cleavage of peptide bonds within the loop then gives rise to a form of the receptor with two subunits (A and B) linked by the disulfide bridge which originally formed the loop,” as is “well established in the cases of several proteins including insulin” and “reduction of the disulfide bridge allows release of the water-soluble A-subunit” (6) (Figure 1A). This concept is entirely consistent with the present understanding of TSHR structure with disulfide bonding between clusters of cysteine residues in groups II and III (7), also termed boxes II and III (8) (Figure 1B). These studies should be regarded in the light of numerous other contemporary studies describing TSHR with one, two, or three subunits, with molecular masses varying between 17 and 200 kDa, either covalently or noncovalently linked (for example, see Refs. 9–13). That the TSHR is coded for by a single mRNA transcript (14–16) provided direct confirmation for the Rees Smith proposal that a single polypeptide precursor undergoes proteolytic cleavage. Also, as described below (Section III), the report of the Rees Smith group regarding disulfide-linked TSHR subunits was confirmed by other investigators. Nevertheless, besides providing clarity, the molecular cloning of the TSHR also generated controversy regarding its subunit structure.

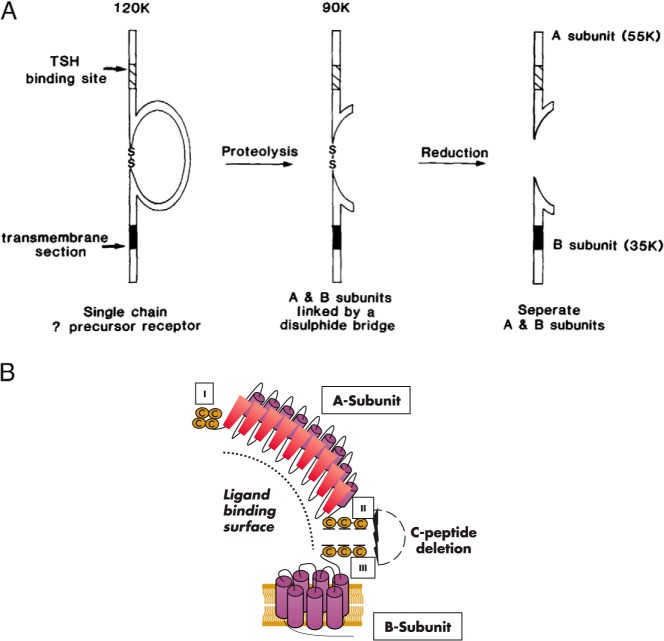

Figure 1.

A, Concept 30 years ago of TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits based on 125I-TSH cross-linking to FRTL5 thyroid cells before molecular cloning of the receptor (6). A single polypeptide chain with an extracellular disulfide-bonded loop was proposed to undergo intramolecular proteolysis with removal of a portion of the loop resulting in two disulfide-linked subunits. Experimentally, these subunits could be separated by reduction of these disulfide bonds. Note the terminology of A- and B-subunits. [Reproduced from Figure 4 in J. Furmaniak et al: Photoaffinity labelling of the TSH receptor on FRTL5 cells. FEBS Lett. 1987;215:316–322 (6), with permission. © Elsevier.] B, Schematic representation of the TSHR as presently understood. Aside from more information on the molecular structure of the A- and B-subunits and the realization that there are seven transmembrane passages in the B-subunit, the basic concept is the same as that proposed 30 years ago. The three cysteine clusters in the TSHR ECD are indicated as I, II and III. The A- and B-subunits are depicted as separated by elimination of disulfide bonding between cysteine clusters II and III. The dotted arc indicates the approximate ligand binding site, in the case of TSH binding extending into the N-terminus of the B-subunit.

III. Does the “Mature” TSHR Comprise Two Subunits or a Single Polypeptide?

In the initial studies on the recombinant TSHR expressed on the surface of stably transfected cells, covalent cross-linking of 125I-TSH revealed two forms of receptors: one comprising two subunits linked by disulfide bonds, and the other a single polypeptide chain of approximately 100 kDa (17). However, TSH cross-linking performed with crude thyroid membrane extracts from these same cells revealed only the two-subunit form of receptor (17). These data fully supported the premolecular cloning reports from the Rees Smith group, who observed both two-subunit and single-chain TSHR when cross-linking TSH to intact FRTL5 rat thyroid cells (6), but only the two-subunit form when employing thyroid plasma membranes or extracts (3–5). This fragility upon cell homogenization raised the possibility that the single-chain TSHR was not only a precursor, as previously suggested (6), but could also be a physiological receptor in vivo highly susceptible to artifactual proteolysis under experimental conditions (17). Factors supporting this possibility were the varying proportion of single and two-subunit TSHRs observed in different experiments as well as the fact that the closely related gonadotropin receptors exist only in single-chain form (18, 19).

Subsequent to these observations, the group of Milgrom et al (20) confirmed the detection of only the two-subunit, disulfide-linked form of TSHR when affinity-purified from detergent extracts of human thyroid membrane preparations. In contrast, Kohn and coworkers (21) using detergent extracts from transfected Cos-7 cell membranes observed primarily single-chain TSHRs of varying sizes as well as minor subunit-sized components (surprisingly not disulfide-linked), which were interpreted as degradation products. On this basis, Misrahi and Milgrom (22) proposed that single-chain TSHRs were only observed in nonthyroid cells, but that “in thyroid tissue, the (TSHR) cleavage is almost complete.” Support for this proposal was that, in their experience, single-chain receptors in transfected nonthyroidal cells were precursors containing high mannose N-linked oligosaccharides as opposed to thyroid tissue in which the only receptors present contained two-subunit receptors with mature, complex glycan components (22, 23). Moreover, these investigators attributed the single-subunit TSHR form detected in transfected nonthyroidal cells to overexpression leading to “saturation of the cellular machinery necessary for processing of the receptor,” thereby leading to accumulation of the high mannose precursor “mistaken for the mature receptor” (22).

IV. What Is the TSH Receptor Subunit Structure on Thyrocytes in Vivo?

The concept promoted by Milgrom et al (22, 23) that the TSHR subunit structure differs between thyrocytes in vivo and cultured thyroid cells or transfected nonthyroidal cells has become generally accepted (for example, see Ref. 24). However, in our opinion and for the following reasons, the present evidence does not support the conclusion that a monomeric TSHR on the cell surface is an experimental artifact that does not occur in the thyroid.

There is presently no technique that can determine the TSHR subunit composition in vivo without first removing the thyroid and testing dispersed cells or thyroid homogenates.

Intact, cultured thyroid cells are the closest representative of the in vivo situation. As mentioned above, FRTL5 rat thyroid cells express both monomeric and dimeric TSHR on their surface (6), an observation independently confirmed (25).

A significant proportion of monomeric TSHRs are present on the surface of intact primary cultures of normal human thyroid cells, as well as human papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma cell lines, as determined by TSH covalent cross-linking, flow cytometry, and confocal microscopy (25). Because of very low endogenous expression in these cells, human TSHR expression was augmented using an adenovirus vector. Nevertheless, these cells contained the natural cellular mechanism(s) involved in TSHR processing.

It has been suggested that transfecting cells with a TSHR expression vector overloads the capacity of the TSHR cleavage mechanism and permits the trafficking of immature high mannose monomeric receptors to the cell surface (22, 23). This criticism can be discounted because the proportion of monomeric to dimeric receptors remains unchanged over a 100-fold variation in TSHR expression levels, ranging from physiological to supraphysiological (25, 26).

Monomeric TSHRs on the cell surface contain mature, complex oligosaccharides, not immature high-mannose moieties (27).

In summary, the foregoing data do not support the conclusion that in vivo the TSHR exists entirely in the two-subunit form. The in vivo situation cannot be determined by present experimental techniques. Furthermore, the single-chain TSHR forms detected on the surface of intact cells in culture are neither immature precursors nor artifacts occurring only in nonthyroidal cells. Rather, detection of mature monomeric TSHRs clearly depends on whether intact cells or cell homogenates are examined. The TSHR is very fragile (for example, see Ref. 28), and cell homogenization readily converts TSHR monomers into the two-subunit form (17).

V. TSH Receptor Subunit Nomenclature

In their pioneering TSH cross-linking studies on thyroid tissue membranes and thyroid cells before the molecular cloning of the TSHR, Rees Smith and coworkers (4–6) annotated the TSH binding and membrane-associated subunits as A and B, respectively (Figure 1A). We confirmed this phenomenon with the recombinant TSHR expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and followed the A and B nomenclature (17). Subsequently, however, on also confirming the Rees Smith data, the Milgrom group (20) altered the terms for these subunits to α and β, now used by some investigators and established in contemporary textbooks. The rationale given for renaming the TSHR subunits to α and β was 2-fold (20). First, before the molecular cloning of the TSHR, the literature was replete with widely divergent reports on the TSHR structure, and the two-subunit structure observed by Misrahi and Milgrom (22) was stated to be “unexpected”; second was an analogy with the insulin receptor subunits (20).

We support retention of the A- and B-subunit nomenclature for the following reasons. First, among the TSHR precloning reports, the Rees Smith data clearly stand out as being unequivocal. When confirmed by the molecular cloning of the TSHR, it is our opinion that credit for the original findings should not be “buried.” Second, TSH, the ligand for the TSHR, has α- and β-subunits, and applying the same terms for ligand and receptor is confusing. Finally, the subsequent discovery of a “C-peptide” region deleted from the TSHR (see Section VI) is more analogous to insulin than to the insulin receptor.

VI. “There Is a Piece Missing in the TSHR”

The realization that a C-peptide region of the TSHR was deleted in association with intramolecular cleavage into subunits arose from studies on chimeric LH receptor (LHR) substitutions within the TSHR that revealed that TSHR cleavage did not occur at a single site. Thus, cleavage was abolished only when two adjacent segments at the C-terminus of the TSH ectodomain (ECD) were replaced with the corresponding regions of the noncleaving LHR (Figure 2A) (29). Substitution of each segment individually did not prevent cleavage. The implication of this finding (only appreciated later) was that more than one cleavage site would lead to deletion of an intervening C-peptide segment (30). The “penny dropped” when it became clear that, after cleavage, (i) the sum of the deglycosylated polypeptide A- and B-subunit chains was smaller (by ∼5 kDa, or 50 amino acids) than the predicted size of the TSH holoreceptor polypeptide, and (ii) by the loss after intramolecular cleavage of an artificial epitope inserted into the cleavage region (30). These data were consistent with tryptic digestion of the TSHR causing the loss of recognition by mouse monoclonal antibody 2C11, whose epitope included six amino acids (residues 354–359) within this region (31, 32).

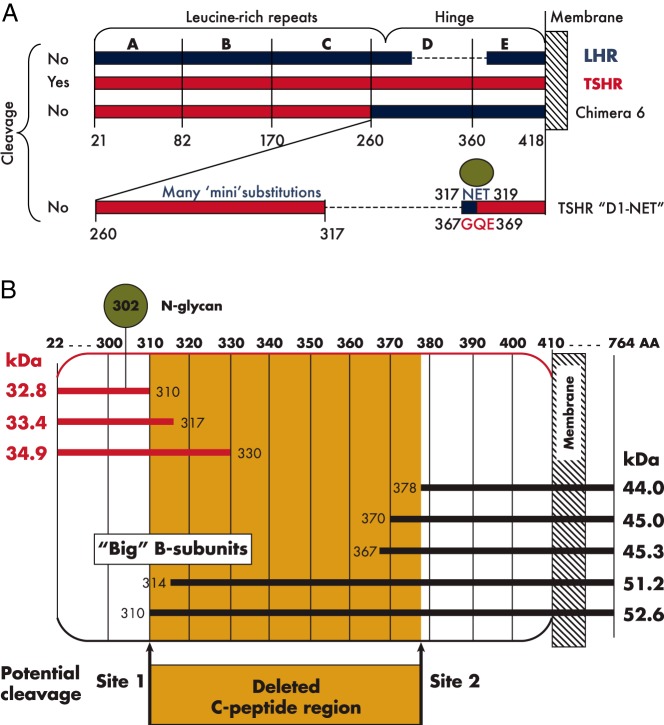

Figure 2.

A, Chimeric TSH-LH receptors used to investigate TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits. Schematic representation of TSHR and LHR components are shown in red and blue, respectively. Only the combined substitution of TSHR domains D and E with the homologous regions of the LHR (chimera 6) abolished TSHR cleavage. Individual substitutions were without effect. Smaller individual chimeric or alanine substitutions throughout the TSHR (termed “mini” substitutions), as well as deletion of the approximately 50 amino acid residues (317–366) present in the TSHR and absent in the LHR, also failed to prevent receptor cleavage. However, the small chimeric substitution of TSHR residues 367–369 with the comparable region of the LHR (residues 317–319) together with deletion of TSHR residues 367–369 did abolish cleavage (TSHR D1-NET). This chimeric substitution eliminates an N-linked glycan (green circle) present in the LHR. B, Schematic representation of TSHR A- and B-subunit sizes depending on the theoretical or experimentally observed size of these subunits. The A-subunit sizes indicated are after enzymatic removal of N-linked glycan moieties. The deleted C-peptide region cannot be isolated experimentally, and therefore appears to be degraded after clipping at two (upstream and downstream) cleavage sites, or, more likely, initial clipping at site 1 site is followed by progressive “salami slicing” downstream to site 2. There is greater consensus regarding the approximate size of the A-subunit (C-terminus between residues 310–330) than for the B-subunit. A minority of B-subunits are near site 1 (hence “big”) and probably represent species formed directly after initial cleavage. The dominant B-subunit species have N-termini at 370 and 378.

VII. Where Are the TSH Receptor Intramolecular Cleavage Sites?

It is now accepted that a portion of the TSHR ECD is removed by cleavage at more than one site. However, it is a common misperception (for example, see Refs. 33 and 34) that this deleted C-peptide comprises precisely 50 amino acid residues, 317–366. Although approximately correct, despite much effort, the precise boundaries of the C-peptide remain unknown.

The basis for the foregoing delineation of the C-peptide was the realization that the TSHR primary amino acid sequence near the C-terminus of the ECD contains an “insert” of 50 or 52 amino acids relative to the equivalent region of the LHR. However, because of low homology in this region of the TSHR and LHR, it is not surprising that there was no concurrence in defining the boundaries of this insertion, suggested to be between TSHR residues 333–384 (14) or residues 317–366 (15). The observation that the more upstream segment (residues 317–366) could be excised experimentally without altering TSH binding and function (15), unlike deletion of the more downstream segment extending to residue 384 (35), favored the former C-peptide delineation. Nevertheless, despite this information, the dimension and boundaries of the C-peptide remain poorly defined.

The following three approaches have been used to assess the TSHR intramolecular cleavage sites.

A. Mutagenesis to prevent or to introduce receptor intramolecular cleavage

As mentioned above, two large chimeric LHR substitutions encompassing over 150 TSHR amino acid residues at the C-terminus of the ECD (segments D and E) abolished intramolecular cleavage into disulfide-linked subunits (29) (Figure 2A). Unexpectedly, scores of smaller LHR chimeric or alanine substitutions (termed “mini” substitutions in Figure 2A) encompassing every amino acid within these regions of the TSHR did not abrogate intramolecular cleavage, suggesting that the unknown cleavage enzyme (Section VIII) lacked amino acid specificity (36, 37). Furthermore, deletion of the 50-amino acid “insert” (putative residues 317–366) did not prevent TSHR intramolecular cleavage into A- and B-subunits. However, TSHR cleavage was abolished by deletion of these 50 amino acids when combined with a small chimeric substitution of TSHR residues 367–369 (GQE) with the corresponding segment of the noncleaving LHR (residues 317–319) (36) (Figure 2A).

Remarkably, in the foregoing noncleaving receptor (termed TSHR D1-NET), the three LHR amino acid residues (317NET319) represent an N-linked glycosylation motif known to contain glycan (38). The cleavage-susceptible TSHR lacks an N-linked glycan in this region. This observation, therefore, raised the possibility that a large glycan moiety at LHR residue 317N prevented intramolecular cleavage by steric hindrance of the enzyme responsible for TSHR cleavage. If this hypothesis was correct, removal of this N-linked glycan should convert the LHR into a cleaved, two-subunit receptor resembling the TSHR. Indeed, mutation of the 317NET319 motif to AAA did generate a substantially cleaved LHR, but a more limited substitution (QET) which also eliminated the N-glycan motif led to minimal LHR intramolecular cleavage (39). Therefore, the role of glycan moieties in the glycoprotein hormone receptor cleavage mechanism remains unclear. An AAA substitution is unlikely to represent a specific site for a proteolytic enzyme, which would be consistent with a lack of amino acid specificity for the enzyme responsible receptor cleavage (Section VIII). Knowledge of the positions of the N-linked glycan motifs on the three-dimensional structures of the glycoprotein hormone receptors would be of value in addressing this issue. Unfortunately, the crystal structure of the TSHR is limited to the leucine-rich repeat domain upstream of the cleavage region (40, 41). Although the molecular structure of the entire ECD of the noncleaving FSH receptor is available (42), much of the relevant portion of the hinge region has not been solved because of a disorder within the crystal, including the critical N-linked glycan at position 318, equivalent to LHR residue N317. No portion of the LHR crystal structure has been reported.

B. Estimation of the masses of A- and B-subunits formed by intramolecular cleavage

The uncleaved, single-chain TSHR polypeptide (without glycan) has a mass of 84.4 kDa (764 amino acid residues, including a 21-residue signal peptide absent in the mature protein). After intramolecular cleavage of the holoreceptor, estimation of the resulting A-subunit and B-subunit sizes by SDS-PAGE under reduced conditions by direct staining or by immunoblotting can provide an approximate location of the cleavage sites. Such estimates require two provisos. First is the use of an antibody that will determine an intact (not partially degraded) molecule, such as to the N-terminus of the A-subunit. Second, because the six N-linked glycans in the TSHR ECD contribute greatly to receptor mass, these moieties require enzymatic removal in order to estimate the size of the polypeptide chain. As a reference for such evaluations, and on the (unlikely) theoretical assumption that the deleted C-peptide comprises precisely 50 amino acids (residues 317–366), the deglycosylated A-subunit polypeptide size (residues 22–316) would be 33.4 kDa, and the B-subunit (residues 367–764) would be 45.3 kDa (Figure 2B).

Turning first to the deglycosylated TSHR A-subunit, although a variety of reports described widely varying sizes with numerous extraneous bands being visible (eg, Ref. 21), more clear-cut data agreed on a size of approximately 35 kDa (23, 27, 30, 43). An A-subunit of approximately 35 kDa with an intact N-terminus would have a C-terminus at approximately amino acid residue 330 (Figure 2B). On the other hand, after light tryptic digestion of TSHR on the surface of intact cells, and using the TSHR N-linked glycan at residue 302 as a marker, the C-terminus of the A-subunit was estimated to be near, or slightly further upstream than, amino acid residue 317 (37). The size of A-subunits shed from the cell surface, not necessarily the entire A-subunit, is discussed separately (see Section IX).

The information regarding the TSHR B-subunit is more complex and confusing. On SDS-PAGE, B-subunits (not requiring deglycosylation because of the absence of N-linked glycan) are described that vary considerably in size, for example, ∼33 kDa and ∼40 kDa (23), ∼42 kDa (30), 40–46 kDa (27), and ∼39–44 kDa (43). Assuming that these highly diverse TSHR B-subunit sizes include an intact C-terminus (amino acid residue 764), a 33-kDa B-subunit can only be a degradation product because it would have a calculated N-terminus at approximately residue 465, thereby lacking the first and part of the second transmembrane helices. On the other hand, the largest reported B-subunit of 46 kDa would have a calculated N-terminus at approximately amino acid residue 360, consistent with other experimental evidence and therefore more likely (Section VII.C).

C. Direct amino acid sequencing of the N-termini of purified B-subunits

Because amino acid microsequencing is initiated at the polypeptide N-terminus, data on the A-subunit would not be informative because TSHR intramolecular cleavage occurs at its C-terminus. However, identification by microsequencing of the B-subunit terminus would be highly informative of the downstream TSHR cleavage site(s).

B-subunits immunopurified from human goiter tissue or from mouse fibroblasts (L cells) stably expressing the human TSHR and subjected to N-terminal amino acid microsequencing revealed a wide spectrum of minor forms, including N-termini at S314, L322, E325, D332, Y353, F356, E357, F366, L370, and T388 (43), with calculated masses ranging from 42.8 to 51.5 kDa. The most abundant B-subunit species had N-termini of L370 and L378 (43) (calculated values of 45.0 and 44.0 kDa, respectively) (Figure 2B).

These data provided evidence that the C-peptide was not “cleanly” deleted by excision at two (upstream and downstream) cleavage sites, as previously suggested (30). Rather, initial cleavage occurred at an upstream site (approximately amino acid residue 314, consistent with the A-subunit mass estimation), thereby generating “big” B-subunits (Figure 2A). Thereafter, progressive clipping of the B-subunit N-terminus generates smaller B-subunits with N-termini in the region of residues 370–378 (43). The inability to purify intact C-peptides after TSHR intramolecular cleavage supported the concept that, rather than there being two distinct cleavage sites, this segment was removed either by N-terminal “salami slicing” or by rapid degradation of the released polypeptide (27).

There are a number of considerations in evaluating the purified B-subunit N-terminus sequencing data. The TSHR is a highly fragile protein that is readily proteolyzed upon homogenization of thyroid tissue or transfected cells (for example, Refs. 17, 28, and 44), even in the presence of standard antiproteolytic agents. The greater heterogeneity of B-subunits purified from transfected fibroblasts than from thyroid tissue (43) suggests that some of the species detected had undergone nonphysiological degradation. As mentioned above, two of the B-subunit species identified were dominant (N-termini of L370 and L378), whereas the other eight species were less abundant (43). This information suggests two alternatives: 1) progressive cleavage from an initial upstream cleavage site that pauses temporarily for an unknown reason at residues L370 and L378 before proceeding further downstream; or 2) there are, indeed, two major cleavage sites (approximately residues 310/314 and 370/378) with the minor species generated by artifactual proteolysis. In summary, regardless of the number of cleavage sites within the TSHR ECD, the end result is the same: 1) a C-peptide (or more accurately, a C-peptide region) is excised from the TSHR expressed on the cell surface; 2) the boundaries of this C-peptide region are poorly defined; and 3) the excised C-peptide region includes the 50-amino acid “insertion” in the TSHR relative to the other glycoprotein hormone receptors, but the boundaries of this region are likely to extend further upstream and downstream, for a total of 60–70 amino acid residues.

VIII. Mechanism of TSHR Intramolecular Cleavage

Two questions arise as to the mechanism by which the TSHR cleaves into two subunits: what is the cellular location, and what is the enzyme responsible for this cleavage?

A. Cellular location of cleavage

The TSHR is a glycoprotein with six N-glycan motifs in the ECD, all of which contain glycan moieties (45). Glycosylation of the receptor polypeptide chain is necessary for proper trafficking to the cell surface (46). As for many other proteins, high mannose precursor oligosaccharides are transferred in the endoplasmic reticulum to asparagine acceptor motifs, followed by oligosaccharide trimming and modification in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, with final complex glycan maturation in the trans-Golgi before trafficking to the cell surface.

Data on the TSHR expressed in eukaryotic cells, when studied in precursor pulse-chase (23, 27), indicate that the cleaved receptor contains complex, not immature high mannose, glycan moieties. Therefore, TSHR intramolecular cleavage occurs either in the trans-Golgi or at the cell surface. The latter alternative was established by a comparison of TSHR restricted to the cell surface vs receptors within the cell, in which cleavage into subunits was observed only in cell surface receptors (Figure 3) (27).

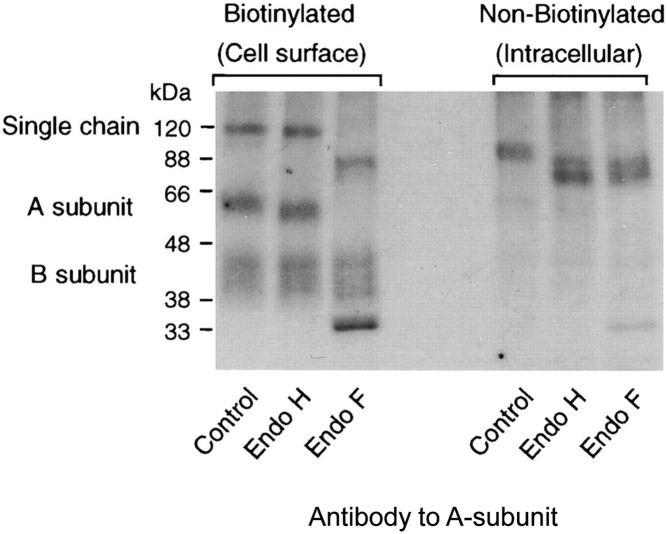

Figure 3.

Both the single-chain and cleaved, two-subunit TSHR expressed on the cell surface contain mature complex glycan moieties. Only single-chain TSHR with immature high mannose glycan moieties are present within the cell. In this representative experiment, TSHR stably expressed by Chinese hamster ovary cells were pulse-chased with radiolabeled amino acid precursors, and receptors present on the cell surface were separated from receptors within the cell, followed by disulfide bond reduction, enzymatic deglycosylation, and autoradiography (27). Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) removes only high mannose glycan, whereas endoglycosidase F (Endo F) removes both high mannose and complex glycan. For cell surface TSHR, single-chain and two-subunit receptors are present that are both resistant to Endo H but deglycosylated by Endo F. Note the very large glycan contribution to the A-subunits, with a post deglycosylation reduction in size from approximately 60 kDa to approximately 33 kDa. The B-subunit lacks glycan moieties and appears as a “smear” extending from approximately 44–40 kDa, indicating a greater susceptibility to degradation. Intracellular single-chain TSHRs are sensitive to both Endo H and Endo F deglycosylation. [Figure was originally published in K. Tanaka et al: Subunit structure of thyrotropin receptors expressed on the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33979–33984 (27), with permission. © The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.]

B. Enzyme responsible for TSHR intramolecular cleavage

The potential clinical importance of this enzyme is that the shed A-subunit, rather than the TSH holoreceptor, is likely to be more important in the induction or affinity maturation of thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies (TSAbs) that cause Graves' disease (47, 48). A-subunit shedding can only occur after TSHR intramolecular cleavage. The enzyme that generates A- and B-subunits from the single-chain TSHR on the cell surface is not definitively established. The cluster of basic residues (arginine and lysine) in the TSHR cleavage region, similar to classical subtilisin-related proprotein convertase endoproteolytic sites involved in numerous mammalian proprotein and prohormone conversions to the mature form (49), were not found to be substrates for the TSHR cleavage enzyme (50).

1. Lack of, or limited, tissue and enzymatic specificity for TSHR intramolecular cleavage

For simplicity, we use the term TSHR “cleavase” pending the definitive identification of the enzyme, a term previously used in the scientific literature (for example, Ref. 51). That the TSHR cleaves into subunits in transfected nonthyroidal cells, as well as in thyrocytes, excludes the possibility that the TSHR cleavase is thyroid specific. Moreover, definitive evidence is lacking that the cleavase recognizes a specific amino acid motif in the TSHR. As mentioned above, extensive TSHR mutagenesis has failed to define such a motif (36, 37). On the other hand, studies to convert the noncleaving LHR to a cleaving receptor similar to the TSHR suggested partial amino acid specificity, although very limited (39). That alanine-scanning mutagenesis at this LHR site was as effective as 317-GQE-319 is supportive of cleavase nonspecificity.

Further evidence against cleavase specificity is that the deletion of the TSHR segment (residues 305–320) containing the initial, proximal cleavage site does not abolish cleavage, but shifts the cleavage site further upstream (52). This evidence supports the likelihood that the TSHR cleavase clips the receptor at a fixed distance from the plasma membrane, regardless of the amino acids at the cleavage site. The term “molecular ruler” has been applied to this phenomenon (53), suggesting that the cleavase is a membrane-associated protease such as an ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloprotease). Support for this concept has been reported for numerous molecules such as pro-TGF (54), pro-TNF (55, 56), angiotensin-converting enzyme (57), amyloid precursor protein (58), and acetylcholine receptor-inducing activity (59).

2. Attempts to identify the TSHR cleavase

Initial information on the cleavase identity was that BB-2116, a synthetic hydroxamic acid matrix metalloprotease (MMP) inhibitor, completely prevented TSHR A-subunit shedding from the surface of transfected fibroblasts (60). Because A-subunit shedding can only occur after TSHR intramolecular cleavage, these data suggested that the TSHR cleavage was an MMP. However, subsequent studies from the same laboratory determined that, unlike BB-2116, tissue inhibitors of MMPs did not inhibit TSHR A-subunit shedding, and the lesser specificity of BB-2116 was noted (43). Because BB-2116 also inhibits a pro-TNFα-converting enzyme (TACE, a member of the ADAM family now identified as ADAM17), it was suggested that the TSHR cleavase was also an ADAM (43). However, TNFα-converting enzyme/ADAM17 itself did not cleave the TSHR, indicating that the receptor cleavase was related to, but nonidentical with, ADAM17 (43). Using a DNA microarray panel representing members of the ADAM family, the TSHR cleavase was reported to be ADAM10, as well as being thyroid specific (61). Whereas ADAM10 is certainly a possibility, it is unlikely to be thyroid specific in that the control tissues studied only included fetal brain and placenta. Moreover, ADAM10 activity is clearly established on substrates in other tissues such as the human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) receptor in breast cancer (62) and amyloid precursor protein in neurons (63). Also, as mentioned above, TSHR cleavage occurs in transfected nonthyroidal cells (eg, Chinese hamster ovary fibroblasts).

Proteases in the ADAM family, presently comprising at least 19 members, also function as “sheddases,” as in the case of ADAM17 releasing TNF from its membrane-associated precursor (reviewed in Refs. 64 and 65). However, in the case of TSHR intramolecular cleavage, it is unclear whether the term sheddase is appropriate because simple cleavage within the C-peptide region would not, by itself, result in A-subunit shedding without dissolution of the disulfide bonds that link the A- and B-subunits.

In summary, present evidence suggests that the TSHR cleavase is likely to be an ADAM, although which member of this family remains to be definitively established. Indeed, given the vast number of substrates relative to the limited number of ADAMs (66), the ubiquitous distribution of ADAMs, as well as their limited substrate specificity and functional redundancy (65), TSHR cleavage may not be restricted to a single protease.

C. Factors influencing TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits

Both single-chain and two-subunit forms of the TSHR are detected on the cell surface, with widely varying estimates of the proportions of each form (for example, Refs. 6, 17, and 23). These observations, together with the potential physiological or pathophysiological significance of the TSHR intramolecular cleavage, have engendered considerable interest in factors that may alter the balance between cleaved and noncleaved receptors. The following are some of these factors:

1. TSH and TSAb

TSHR cleavage into subunits has classically been studied by 125I-TSH cross-linking (3), a method used subsequently in many other studies (reviewed in Ref. 7). Because of the precedence that a ligand such as thrombin can cleave its cognate receptor (67), a direct action of TSH on the TSHR was considered, but was then discarded because TSHR cleavage assessed by tracer TSH cross-linking occurs even in transfected nonthyroidal cells not exposed previously to TSH (68). However, the question of TSH functioning as a TSHR cleavase or, more likely, facilitating cleavage by another enzyme remains open (69). Early studies suggested that TSH (at high concentration and under unphysiological conditions) had a small but significant stimulatory effect on A-subunit shedding (60). TSHR A-subunit shedding can only occur after holoreceptor intramolecular cleavage. Whether TSH under these conditions influences cleavage, shedding, or both could not be determined.

More recently, Davies and colleagues (70) assessed TSHR cleavage independent of A-subunit shedding in a flow cytometry assay employing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to distinguish between receptors that retained the C-peptide region (both cleaved and uncleaved TSHR) and receptors that had lost the C-peptide region (only cleaved TSHR) (Figure 4). In this assay, TSH, but not a monoclonal mouse TSAb, increased the proportion of cleaved TSHR by 75%. By extending the duration of TSHR expression on the cell surface, this phenomenon was suggested to explain the “prolonged overstimulation of the thyroid gland in Graves' disease” (70). A subsequent study by Chazenbalk et al (71) was unable to reproduce these data using a different set of mAbs to distinguish between cleaved and uncleaved TSHR and also observed that prolonged, high-dose TSH pretreatment followed by stringent washing was without effect on TSHR cleavage as determined by 125I-TSH cross-linking. A follow-up study by Latif et al (72) confirmed the contrary findings reported by Chazenbalk et al (71) when using the same TSHR C-peptide-specific mAb employed by the latter, as well as the lack of TSH-induced cleavage when assessed by 125I-TSH cross-linking.

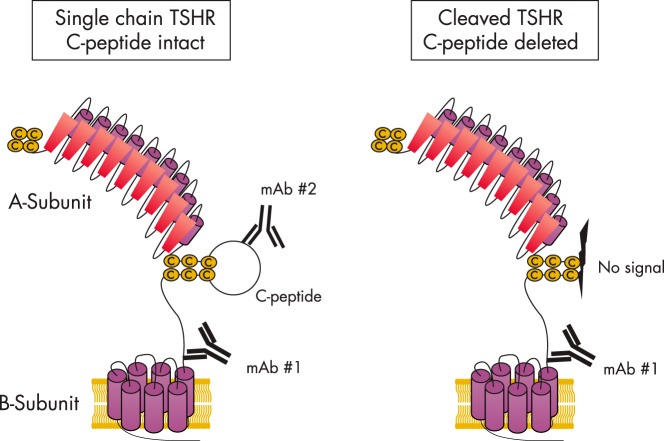

Figure 4.

Flow cytometric subtractive assay to estimate the proportion of cleaved vs uncleaved TSHR on the cell surface. Monoclonal antibody 1 to the extracellular component of the B-subunit recognizes both cleaved and uncleaved receptors, as well as in cleaved receptors that have already shed their A-subunits. Monoclonal antibody 2 is to the C-peptide loop present only in the single-chain, uncleaved TSHR. Because this antibody cannot “see” the cleaved, two-subunit TSHR that has lost its C-peptide region, the difference between the signals for antibodies 1 and 2 estimates the proportion of cleaved vs uncleaved TSHR. Potential limitations to interpreting data obtained with this assay are described in the text.

A number of theoretical explanations have been proposed to explain these differences. Davies and colleagues (72) suggested that the choice of the correct C-peptide-specific mAb was critical and that 125I-TSH cross-linking is inadequate for examining “dynamic changes in TSHR forms.” On the other hand, 125I-TSH cross-linking provides a “snapshot” at a particular time of both cleaved and uncleaved cell TSHR simultaneously, with the proportion of cleaved to uncleaved TSHR corroborated by precursor pulse-chase experiments (27). The flow cytometric, dual mAb approach is a subtractive, proportional assay that does not directly detect the cleaved receptor (Figure 4). The baseline “numerator” measurement in this assay excludes cell surface TSHRs that have already cleaved (>50% of receptors) before the addition of TSH. Use of a mAb to the extreme C-terminus of the ECD (70, 72), rather than a polyclonal Ab raised to the entire TSHR lacking only the C-peptide region (71), will also overestimate the “denominator” because it will detect receptors with “bare” B-subunits whose A-subunits have already been shed, estimated to be 2- to 3-fold more prevalent than receptors with A-subunits (20, 27). Finally, a corollary to the concept that Graves' TSAbs enhance thyroid stimulation by prolonging TSHR residence on the cell surface (less cleavage and shedding) is the unlikely occurrence that a high TSH level in primary hypothyroidism would reduce the efficiency of thyroid stimulation by increasing cleavage and shedding.

2. TSHR multimerization

There is evidence that TSH holoreceptors on the cell surface exist as multimers (for example, see Refs. 73 and 74). However, the number of TSHR protomers in this multimeric structure is unknown. Information on the crystal structures of the isolated TSHR leucine rich domain (LRD) component (a monomer) (40) or the trimeric FSH receptor ECD (LRD + hinge) (42) cannot be extrapolated to the full TSH holoreceptor in the plasma membrane (LRD + hinge + transmembrane domain [TMD]), although there is evidence that the FSH holoreceptor is present in the membrane as a functional trimer (75).

Regardless of the number of TSHR protomers, using the dual-antibody flow cytometry assay (70) (Figure 4) to determine TSHR cleavage, it has been suggested that only the monomeric, and not the multimeric, form of the TSHR on the cell surface undergoes intramolecular cleavage into subunits (72). There are two bases for this proposal. First, TSH, but not TSAb, is reported to dissociate constitutive TSHR multimers into their monomeric protomers (76), although this finding was not confirmed in another study (74). Second, a monovalent Fab and not the bivalent parent IgG reduces the proportion of uncleaved TSHRs relative to the total number of receptors detected on the cell surface. It is proposed that intact IgG TSAbs immobilize TSHRs in their multimeric forms, thereby preventing cleavage into subunits and subsequent A-subunit shedding (72). These interesting data, which await confirmation by another methodology, assume that the angle between the arms of a bivalent IgG can accommodate both protomers in a TSHR dimer.

3. Regulation of the interaction between ADAMs and the TSHR

There is much recent information on the regulation of ADAM-mediated cleavage of the extracellular regions of numerous membrane-associated molecules. However, there are no clear paradigms that can be applied to the TSHR. Typically, ADAMs release functional molecules such as growth factors in a rapid and regulated manner, and there is no known physiological function of the shed TSHR A-subunit, as opposed to the potential pathological consequences in Graves' disease (Section XI). Furthermore, in the case of CD44, a cell surface glycoprotein involved in cell-cell interactions, homodimerization is a precondition for ADAM cleavage and release of the former's ECD (77), contrary to the proposal that only the TSHR monomer is subject to cleavage. Finally, for molecules such as CD44 with single-pass transmembrane molecules, there is evidence that a shift in the relative orientation of protomers caused by an intracellular signal activates the previously silent interaction between substrate and an ADAM (77). In the case of the TSHR, there is no present evidence linking cleavage to an intracellular signal, and an intracellular signal causing a shift in the orientation to each other G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) protomers with “seven-pass” TMDs is more difficult to conceptualize than for single-pass TMDs.

Of interest in regard to the TSHR, it has been reported that the “silent” interaction between different membrane protein substrates and an ADAM varies greatly. Thus, only a small proportion (∼15%) of CD44 molecules is subject to cleavage (78), whereas the association between ADAMs and neuregulin-1 may approach 100% (77). It is remarkable that in many scores of experiments, the proportion of single-chain TSHR on the cell surface persists in the 30–50% range (for example, see Ref. 27) (Figure 3), consistent with the foregoing evidence for other cell surface proteins.

4. Neutral autoantibodies

Some monoclonal TSHR antibodies derived from hamsters vaccinated with adenovirus expressing the human TSH holoreceptor neither activate the receptor via the dominant Gsα/cAMP pathway nor compete for TSH binding (79, 80). These “neutral” antibodies were observed to inhibit TSHR cleavage into subunits (33) using the flow cytometric, dual mAb approach (80). Unlike previously recognized pathogenic TSHR autoantibodies (both human and mouse), most of these hamster neutral antibodies recognize linear epitopes (synthetic peptides) within the C-peptide region deleted by intramolecular cleavage of the single-chain TSHR on the cell surface (79, 80), a logical location for an inhibitor of TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits. As described below (Section X.D), neutral antibodies are no longer considered to be truly neutral, in that they are reported to activate signal pathways not involving Gsα.

5. Cell-cell contact

An intriguing observation is that TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits is influenced by cell-cell contact. In these elegant experiments using transiently transfected mouse L cells, the laboratory of Ghinea and colleagues (81) reported that TSHR cleavage is negligible when cells are sparse and increases progressively with plating density. Thus, when sparse, 30–40% of TSHR remained uncleaved, whereas in highly confluent cells maintained in culture for a longer period, TSHR cleavage was almost complete. The authors suggest that these observations reconcile previous discrepant data regarding the extent of TSHR cleavage (Section III).

Although a varying degree of cell-cell contact is a reasonable explanation for the wide variation in TSHR cleavage reported previously, other methodological differences should also be considered, in particular immunoblot analysis of TSHR cleavage in scraped cell homogenates vs 125I-TSH cross-linking to intact cells in monolayer culture. Cross-linking with 125I-TSH, in which the proportion of uncleaved TSHR typically varies between 30 and 50%, is also generally conducted with overconfluent cells to reduce long autoradiographic x-ray exposures (25). These provisos aside, Ghinea and colleagues (81) appropriately point out that their studies “apply only to TSHR-expressing cell lines and cannot be extrapolated with certitude to the situation in vivo.”

The foregoing report by Ghinea and colleagues (81) is of particular interest because it supports the evidence for involvement of an MMP or, more likely, an ADAM protease(s) in TSHR intramolecular cleavage. Unlike MMPs, the disintegrin component in ADAMs can mediate cell-cell interactions by binding integrins (64). Cell density can increase ADAM cleavage and shedding of cell surface proteins, for example by ADAM-10 clipping some receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (82). ADAMs also play a major role in enabling carcinoma cell invasion and metastasis (reviewed in Ref. 65). With this background, it is counterintuitive that TSHR cleavage into subunits was observed to be reduced in monolayers of human thyroid carcinoma cells relative to primary cultures of human thyrocytes (25). Again, these data obtained by transfection of the human TSHR cannot be extrapolated to the in vivo situation.

6. The TSHR TMD

Assessed by 125I-TSH cross-linking, replacement of the TSHR septahelical TMD with a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor greatly reduces the proportion of cleaved vs uncleaved receptors expressed on the cell surface (83). Because the ECD in both receptor forms is identical, these data support the concept that a membrane-associated, not a soluble, cleavase is responsible for ECD intramolecular cleavage within the TSHR hinge region.

There are a number of possible factors underlying the major effect of the TSHR TMD on the extent of TSHR ECD cleavage, including:

The TMD, unlike the GPI anchor, may function as a docking platform for the ECD cleavase.

The TSHR TMD may alter the conformation of the cleavase substrate (the TSHR hinge region). In support of this possibility, the presence or absence of the TSHR TMD alters the kinetics of TSH binding to the ECD, which must involve a conformational change (84).

The membrane-associated cleavase may be largely excluded from lipid rafts (85), microdomains enriched with cholesterol and sphingolipids, resulting in a physical separation between enzyme and substrate. In common with other GPI-tethered membrane proteins, the TSHR ECD-GPI molecule preferentially segregates within lipid rafts (86). On the other hand, there is considerable evidence that the distribution of wild-type TSH holoreceptors, particularly in multimeric form, is biased toward lipid rafts (87, 88), although not in a subset of caveolae-associated lipid rafts (86). Because TSHR monomers distribute both within and outside lipid rafts (88), it is likely that the TSHR monomer is preferentially subject to intramolecular cleavage. Support for this concept is that when the isolated TSHR ECD is tethered to the plasma membrane by a TMD of CD8α (a cell surface glycoprotein found on most cytotoxic T lymphocytes) the extent of TSHR cleavage is similar to that of the wild-type TSHR (83). Unlike GPI anchors, the CD8α membrane-spanning region is not associated with lipid rafts (89).

7. Artifactual experimental conditions

It is essential, in interpreting the literature on TSHR intramolecular cleavage, to appreciate the difficulty in studying this phenomenon, as well as the potential for artifactual confounding influences. Some of these factors have previously been described, such as the fragility of the TSHR and its susceptibility to proteolysis on tissue or cell freeze-thawing or homogenization (17, 28). General protease inhibitor “cocktails,” unlike inhibitors of MMP or ADAM activity, are insufficient to prevent TSHR degradation. Suboptimal culture conditions such as serum starvation-rendering cultured cells “sick” also influence TSHR cleavage and A-subunit shedding (see Section IX).

IX. Mechanism of A-Subunit Shedding

TSHR A-subunit shedding from stably transfected fibroblasts as well as from cultured human thyrocytes was first reported by Couet et al (60). No shedding of a portion of the ECD was observed in similar experiments with cells expressing the noncleaving LHR (60), consistent with ECD intramolecular cleavage being a prerequisite for subsequent shedding. Because the A-subunit in the cleaved TSHR remains linked to the membrane-associated B-subunit by disulfide bonds (Figure 1), shedding of the former requires dissolution of these bonds. Although it is not feasible to explore the mechanism that occurs in vivo, two mechanisms have been proposed based on experiments utilizing cultured cells expressing the TSHR.

A. Disulfide bond reduction by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI)

PDI is an enzyme whose functions include facilitating correct protein folding by accelerating the formation and dissolution of disulfide bonds between cysteine residues (reviewed in Ref. 90). Although in eukaryotic cells most PDI is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, the enzyme has also been detected at the plasma membrane, linked noncovalently to other membrane proteins, where it functions primarily as a reductase (91, 92). A membrane-impermeable inhibitor of PDI [5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)], as well as monoclonal anti-PDI antibodies, substantially reduced A-subunit shedding, supporting the concept that PDI was responsible for the latter phenomenon (22, 93). This report also raised the possibility that TSH, the cognate ligand for the TSHR, could itself have PDI activity because of a previous report that closely related FSH and LH had thioredoxin activity (94), taken together with the observation that TSH enhanced TSHR A-subunit shedding (60).

Although involvement of PDI in TSHR A-subunit shedding is certainly possible, it should be appreciated that the foregoing studies were performed with cells cultured in medium in which the fetal calf serum content was reduced from 10% to 1%. Without this modification, A-subunit shedding was very low, and serum starvation increased shedding 5-fold (60).

B. Proteolytic removal of cysteine residues in the polypeptide chain

An alternative explanation for a physiological action of PDI on TSHR A-subunit shedding (60) by reducing disulfide bond A- and B-subunit linkage (60) is that suboptimal culture conditions increased A-subunit shedding by unphysiological proteolytic removal of cysteine residues involved in this linkage. Support for this alternative explanation is 2-fold:

The A-subunit shed by cells cultured in medium containing only 1% fetal calf serum was 7 kDa smaller than the A-subunit remaining attached to the B-subunit (∼53 kDa vs ∼60 kDa), yet after enzymatic deglycosylation, the polypeptide chain of both A-subunit forms was similar (∼35 kDa) (60), a difference attributed to glycosidases present in the culture medium (60). However, studies from another laboratory indicated that most A-subunits shed under low-serum (1%) conditions, but not from cells cultured in serum replete (10%) medium, were clipped at their C-termini with deletion of Cys-283 and Cys-284, residues involved in disulfide linkage to the B-subunit (44). This deletion would also remove the glycosylation moiety at Asn-301, producing the same result as enzymatic deglycosylation. Clipping of the B-subunit N-terminus was also observed, suggesting that serum starvation removed subunit-linking cysteine residues in both the A- and B-subunits (Figure 1B).

Nutrient depletion, including serum starvation, of cultured cells is well recognized to cause autophagy of intracellular cytoplasm and organelles (95), a nonselective degradation mechanism distinct from the more specific ubiquitin–proteasome system (reviewed in Ref. 96). As is evident from light microscopy, serum-starved cells expressing the TSHR appear very sick (44), to be expected of cells devouring their own organelles. It is possible that membrane “leakiness” in sick cells leads to the unphysiological release of lysosomal enzymes into the medium. Release of PDI from the endoplasmic reticulum into the medium with subsequent TSHR disulfide bond reduction at the plasma membrane is less likely because, in this case, the shed A-subunit would be intact.

Nevertheless, despite the likely unphysiological effect of serum starvation on the shedding of clipped TSHR A-subunits, it is important to note that with cells cultured in serum-replete medium, shedding of full-sized A-subunits into the culture medium does occur, although quantitatively to a much lesser extent (44).

X. Does TSHR Intramolecular Cleavage Have Functional Consequences?

Because TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits with consequent A-subunit shedding is unique among the glycoprotein hormone receptor, there has been much speculation and experimental probing in search of a functional consequence(s) for this phenomenon. This issue can only be addressed experimentally by comparing the functions of cleaved (two-subunit) and uncleaved (single-chain) receptors. A corollary of this point is that it is necessary that a significant proportion of mature TSHRs on the cell surface are in the uncleaved, single-chain form. In other words, it cannot be argued that all TSHRs on the cell surface in vivo are cleaved (for example, see Refs. 69, 97, and 98), whereas at the same time looking for a functional difference between cleaved and uncleaved receptors. For the reasons posited in this review (see Section IV), it is assumed that both cleaved and uncleaved TSHRs are present on the cell surface.

A. TSH binding affinity

Radiolabeled TSH cross-linking to wild-type TSHR stably expressed on the surface of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells reveals both cleaved and uncleaved receptors. In semiquantitative competition studies, similar concentrations of unlabeled TSH competed for 125I-TSH cross-linking to both forms of TSHR, cleaved and uncleaved (17). These data suggested that TSHR intramolecular cleavage did not alter TSH binding affinity.

In contrast to TSH cross-linking to one cell line expressing the wild-type TSHR, classical, more quantitative TSH binding kinetic analysis for cleaved and uncleaved receptors can only be performed using two separate cell lines, each expressing one or the other receptor form. A noncleaving TSHR, termed D1-NET (see Section VII.A), is available for this purpose (Figure 2A). The TSH binding affinities to the cells expressing the wild-type TSHR and noncleaving TSHR D1-NET, in the nanomolar range, were not significantly different (68).

A drawback to any mutated TSHR is the possibility of a significant allosteric conformational change resulting in artifactual data. In particular, deletion of 50 amino acids (residues 317–366) in the TSHR C-peptide region could affect the relative orientation to each other of the upstream and downstream receptor components. Evidence against this likelihood is that these 50 amino acids form part of a Cys-linked polypeptide “peduncle” that is removed physiologically to form the two-subunit TSHR. Furthermore, the TSH cross-linking data to the wild-type TSHR, although less precise, support the lack of effect of TSHR intramolecular cleavage on the TSH binding affinity.

B. TSH activation of the TSHR

Although TSH binding to the TSHR activates a number of signaling pathways, like the other glycoprotein hormone receptors, the dominant and most sensitive response is via Gsα activation of adenylyl cyclase with subsequent cAMP generation (99, 100). Obviously, TSH stimulation of cAMP generation by cleaved and uncleaved TSHR cannot be determined in the same cell line. However, comparison of separate cell lines stably expressing the wild-type TSHR (cleaved and uncleaved) and TSHR D1-NET (only uncleaved) revealed highly similar cAMP responses to TSH stimulation (68).

The conclusion that TSH stimulation of cAMP generation is unrelated to whether or not the TSHR is cleaved into subunits has been challenged in coimmunoprecipitation experiments in which Gsα was only detected with cleaved receptors (101). A unifying concept taking this information with previously obtained data would be that TSH progressively: 1) dissociates TSHR multimers into monomeric forms (76); 2) facilitates monomeric TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits; and 3) that only the cleaved (not uncleaved) TSHR can activate adenylyl cyclase.

However, as mentioned above, TSH-induced TSHR multimer dissociation has not been confirmed (74), and TSH-induced intramolecular cleavage of TSHR monomers remains controversial (Section VIII.C.1). Finally, the TSHR/Gsα coimmunoprecipitation data represent indirect evidence for TSHR activation, as opposed to direct measurement of cAMP generation. Altogether, an assessment of the foregoing information did not point to TSHR cleavage being “an appealing regulatory step” (69).

Aside from the adenylyl cyclase/cAMP pathway, there is evidence that TSHR cleavage may play a selective role in activation of a different signaling pathway. In contrast to the Gsα pathway, TSH stimulation of the noncleaving TSHR D1-NET does not lead to Gqα activation, as measured by phosphoinositol generation (81).

C. Relation between TSHR cleavage and receptor constitutive activity

The TSHR exhibits relatively high ligand-independent, or constitutive, activity (102), potentially important in therapy of thyroid carcinoma metastases when TSH suppression with exogenous T4 will be insufficient to “quieten” intrinsic TSHR activity (103). High TSHR constitutive activity also explains the relatively limited extent of secondary hypothyroidism (absence of TSH) in comparison to total thyroidectomy. This already high activity is increased further by removal of the entire TSHR ECD (104) or portions of the ECD (105, 106). In this sense, by suppressing constitutive activity, the TSHR ECD serves as an inverse agonist. Similar to ECD deletions by mutagenesis, light trypsinization of the wild-type TSHR expressed on the surface of transfected cells also enhances TSHR constitutive activity (32). Light trypsinization, however, leaves most of the TSHR ECD intact and only removes a small portion near the C-terminus of the ECD (32), subsequently identified to be at the N-terminus of the C-peptide region deleted physiologically during intramolecular cleavage into the two-subunit TSHR form (44, 107). Indeed, the identical trypsinization protocol that enhances constitutive activity converts all single-chain TSHR on the cell surface into receptors with A- and B-subunits, as determined by 125I-TSH cross-linking (107).

The foregoing observations raise the possibility that an important physiological consequence of TSHR cleavage is to regulate the degree of ligand-independent constitutive activity. However, there is no direct evidence in support of this concept, and present evidence is to the contrary. No difference in constitutive activity was observed between cells expressing the wild-type TSHR compared to the noncleaving TSHR D1-NET (68). Moreover, after insertion of a thrombin recognition motif in the cleavage region of TSHR D1-NET, exposure to thrombin converted the noncleaving receptor into one with A- and B-subunits without enhancing constitutive activity (108).

D. “Neutral” antibodies and TSHR intramolecular cleavage into subunits

As mentioned above (Section VIII.C.4), neutral hamster mAbs were observed to inhibit TSHR cleavage into subunits, as detected by the flow cytometric, dual mAb approach (80). Remarkably, rather than being neutral, these TSHR mAbs were reported to possess unusual and unexpected functions, namely the ability to signal via multiple pathways not utilized by TSH and not involving Gsα (33). Synthetic peptides corresponding to the C-peptide region recognized by these neutral TSHR mAbs can compete for the binding of autoantibodies in most Graves' sera to the TSH holoreceptor, suggesting the presence of such neutral Abs in human disease (33).

Stimulating TSHR antibodies (TSAbs) and neutral antibodies are proposed to provide a balance between thyrocyte proliferation and apoptosis accompanied by thyroid lymphocytic infiltration (109, 110). On the one hand, TSAbs activate the PKA/CREB and AKT/mTOR/S6K signaling pathways and actively suppress pathways leading to proapoptotic mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation, whereas neutral TSHR antibodies only activate the latter pathway, tipping the balance toward thyrocyte apoptosis. Release of DNA from apoptotic thyrocytes is proposed to activate innate and bystander immune reactivity.

An interesting corollary to the functional effects of neutral TSHR antibodies relates to the controversy regarding the balance between cleaved and uncleaved TSHR on the surface of thyrocytes in vivo. Despite contrary evidence (see Section IV), more recent reports (including from the group reporting on neutral TSHR antibodies) (111) maintain that cleaved TSHRs are the dominant form present on thyrocytes in vivo, and that single-chain TSHRs on the cell surface are an experimental artifact. Neutral antibodies are reported to interact specifically with the TSHR C-peptide region that is not present in the cleaved, two-subunit receptor (33). Therefore, either there is a significant proportion of single-chain TSHR on the thyrocyte surface in vivo or neutral TSHR antibodies are not of pathophysiological importance. Finally, another discrepancy in the functional data awaits resolution. The report that TSHR signaling via the Gqα pathway is markedly reduced with the uncleaved vs the cleaved receptor (81) is contrary to the proposed action of neutral TSHR autoantibodies that are reported to activate Gqα by binding to the TSHR C-peptide region (33). TSHRs that retain the C-peptide region remain uncleaved.

XI. A Pathophysiological Role for TSHR A-Subunit Shedding?

Aside from the question of a functional difference between the cleaved and uncleaved TSHR (discussed above), a second question then arises as to whether the free TSHR A-subunit shed from the thyrocyte surface is of pathophysiological significance or is simply an unimportant quirk of nature.

A. Are shed TSHR A-subunits present in serum in vivo?

In 1992, Murakami et al (112), using a rabbit antiserum raised to a TSHR ECD synthetic peptide, reported the detection of a “TSHR-like substance” of approximately 60 kDa in human plasma, highest in patients with Graves' disease, and suggested that a soluble form of the TSHR ECD released into blood may contribute to the pathophysiology of Graves' disease. Although not definitively characterized at the time, the mass of this molecule is compatible with the glycosylated TSHR A-subunit. Subsequently, Couet et al (60) reported preliminary experiments (data not shown) in which TSHR A-subunits were affinity-purified from human serum and also suggested that this phenomenon “could be implicated in the pathogenesis of certain autoimmune diseases.” Unfortunately, to our knowledge, over the following 20 years there have been no reports to confirm either observation.

In our view, it is unlikely that TSHR A-subunits will be detected in serum, for a number of reasons.

As a source of A-subunits, the number of TSHR expressed on the surface of thyrocytes is very low, estimated to be only approximately 5000 per cell (113), orders of magnitude lower than for transfected cells (26).

From pulse-chase experiments, the TSHR turnover rate appears to be slow (hours) (23). After exposure to TSH, there is evidence that TSHRs remain on the cell surface and continue to signal for several hours, also suggesting a relatively slow receptor turnover rate (114).

TSHR A-subunit clearance from plasma in vivo is likely to be rapid because of renal filtration (smaller than albumin) and endocytosis of the highly glycosylated protein by hepatocytes and Kupffer cells.

TSHR A-subunits could not be affinity-purified from large serum volumes obtained from transgenic mice overexpressing human A-subunits targeted to the thyroid gland (115).

B. Can shed TSHR A-subunits in serum bind TSH?

Assuming that TSHR A-subunits are present in serum but are not detected because experimental methods are insufficiently sensitive, it has been proposed that these molecules can influence thyroid function by binding TSH and acting as a foil or sink with “down-regulation of hormone action” (93). Such an action of shed receptor ECDs is now appreciated to be particularly important for modulating signaling in the immune system (reviewed in Ref. 116). Indeed, a TSH-binding protein has been reported to occur in the sera of Graves' patients, with the characteristics of a soluble TSHR component (117). Again, there has been no subsequent confirmation of this observation, and whether this potential TSH-binding protein represents the shed TSHR A-subunit or an ECD component translated from a truncated TSHR mRNA splice variant (118, 119) is unknown. On the other hand, experimental evidence suggests that TSH, unlike TSHR autoantibodies, is unable to bind to a recombinant TSHR ECD component (amino acid residues 22–289) comparable to the shed A-subunit (120).

C. Evidence that shed TSHR A-subunits play a role in the pathogenesis of Graves' disease

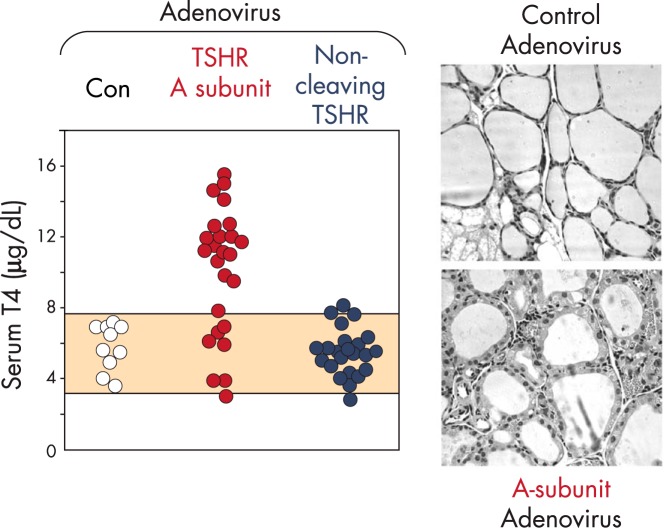

Animal models of disease provide the opportunity to evaluate potential pathophysiological mechanisms by approaches not possible in humans. In addition, Graves' disease occurs only in humans, and not even in great apes that are most closely related to humans in evolution (121). However, the quest for an animal model for Graves' disease proved elusive for decades until finally enabled by the molecular cloning of the TSHR (122, 123). Overcoming serious limitations inherent to these models by immunization of rodents with adenovirus coding for the human TSHR (124) provided the opportunity to address the question of a role for the shed TSHR A-subunit in the pathogenesis of Graves' disease. Immunization with a TSH holoreceptor modified to prevent intramolecular cleavage and A-subunit shedding was highly inefficient in generating TSAb and hyperthyroidism. In contrast, immunization with the free A-subunit induced TSAb and hyperthyroidism in most mice (47) (Figure 5). The greater efficacy of the free A-subunit vs the TSH holoreceptor in inducing experimental Graves' disease has been confirmed in other studies (125–127), and this modification is now used by most investigators (for example, see Refs. 128–133). Finally, transfer of the human TSHR A-subunit transgene to the thyroid of NOD-H2h4 mice, with a genetic background making them susceptible to autoimmune thyroiditis, leads to the spontaneous development of pathogenic autoantibodies to the human (not mouse) TSHR (134).

Figure 5.

Evidence in a mouse model that TSHR A-subunit shedding is required to induce Graves' hyperthyroidism. BALB/c mice were immunized with adenovirus expressing the isolated human TSHR A-subunit or a human TSHR that is unable to cleave into A- and B-subunits (D1-NET; Figure 2A). Control mice (Con) received adenovirus coding for a nonspecific antigen. Mice were injected three times at three weekly intervals. Serum T4 levels were measured at the time of euthanasia 4 weeks after the final adenovirus injection. The shaded area represents the normal range in the control group of mice. Relative to the control mice, the thyroid histology of a representative mouse immunized with A-subunit adenovirus revealed a more columnar and vacuolated epithelium consistent with hyperthyroidism.

Rather than TSHR A-subunits being shed into plasma and detected experimentally in serum, we consider it more likely that shed A-subunits are released into thyroidal lymphatics that drain to regional lymph nodes where they are captured and processed by antigen-presenting cells. Indeed, mannose receptors expressed on such cells (135) bind highly glycosylated TSHR A-subunits (136), suggesting a mechanism by which minute amounts of this antigen, processed into peptides and presented to T-cells, could in turn lead to a humoral TSAb response, the direct cause of Graves' disease.

Antibodies generated to a specific antigen are initially coded for by B-cell germline genes and are, therefore, of low affinity. Subsequent capture by such B-cells of conformationally intact antigen (not peptides) by cell surface Ig “receptors” leads to B-cell proliferation, Ig gene mutations, and class-switching to generate IgG class antibodies with progressively higher affinities (reviewed in Ref. 137). Recent evidence suggests that affinity maturation of high-affinity TSHR autoantibodies in Graves' patients is induced by multimeric TSHR A-subunits (138). As mentioned previously, there is strong evidence that TSH holoreceptors on the thyrocyte surface exist as multimers (for example, see Refs. 73 and 74). Therefore, it is possible that the A-subunits are shed from these holoreceptors as multimers, or form multimers postshedding, for example in draining regional lymph nodes.

XII. Conclusions and Phylogenetic Divergence of the TSHR From the Gonadotropin Receptors

Why the mammalian TSHR has evolved with a hinge region approximately 50 amino acids longer than the gonadotropin receptors is an intriguing question. Phylogenetically, TSH as a hormone distinct from the gonadotropin hormones was not present in the adenohypophysis prevertebrate hagfish (Myxini) when they developed approximately 550 million years ago (139). The first documentation of a glycoprotein hormone receptor similar to the TSHR is in the earliest vertebrates (lamprey; Petromyxontida) that arose approximately 350 million years ago (140). Remarkably, even in this primitive lamprey TSHR, the hinge region has approximately 70 additional amino acids in the hinge region relative to the gonadotropin receptor (Protein Data Bank loci AAW80619 and AAW80618, respectively), with an approximately 50 amino acid “insertion” persisting to the present in the mammalian TSHR. Only the TSHR with a unique hinge region insertion (and not the gonadotropin receptors) cleaves into subunits with consequent shedding of the disulfide-tethered A-subunit.

Did this evolutionary divergence between the TSHR and gonadotropin receptors convey an advantage, or was it an inconsequential evolutionary fluke? The present evidence suggests that TSH recognizes and activates the TSHR regardless of whether the latter is an uncleaved single-chain polypeptide or cleaved into subunits with the C-peptide deleted, at least with respect to its major Gsα signaling pathway. In addition, TSHR intramolecular cleavage does not appear to convey an evolutionary advantage with respect to ligand specificity. Thus, TSHR cleavage does not influence the specificity for TSH and gonadotropin binding to their cognate receptors.

Is it possible that an evolutionary fluke with presently unknown physiological consequences nevertheless created an unfortunate immunological vulnerability leading to Graves' disease in humans? Because TSHR cleavage and A-subunit shedding presumably occur in all humans, such shedding may be necessary, but is not sufficient, for the development of Graves' disease. Multiple additional contributing factors are clearly involved in disease pathogenesis, particularly a genetic background associated with disease susceptibility, a subject beyond the scope of the present review.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK19289 (to B.R.) and DK54684 (to S.M.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ADAM

- a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- ECD

- ectodomain

- GPI

- glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol

- LHR

- LH receptor

- LRD

- leucine rich domain

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- MMP

- matrix metalloprotease

- PDI

- protein disulfide isomerase

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- TSAb

- thyroid-stimulating autoantibody

- TSHR

- TSH receptor.

Reference

- 1. Pastan I, Roth J, Macchia V. Binding of hormone to tissue: the first step in polypeptide hormone action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:1802–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amir SM, Carraway TF, Jr, Kohn LD, Winand RJ. The binding of thyrotropin to isolated bovine thyroid plasma membranes. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:4092–4100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buckland PR, Rickards CR, Howells RD, Davies Jones E, Rees Smith B. Photo-affinity labelling of the thyrotropin receptor. FEBS Lett. 1982;145:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buckland PR, Howells RD, Rickards CR, Rees Smith B. Affinity-labelling of the thyrotropin receptor. Characterization of the photoactive ligand. Biochem J. 1985;225:753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kajita Y, Rickards CR, Buckland PR, Howells RD, Rees Smith B. Analysis of thyrotropin receptors by photoaffinity labelling. Orientation of receptor subunits in the cell membrane. Biochem J. 1985;227:413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Furmaniak J, Hashim FA, Buckland PR, et al. Photoaffinity labelling of the TSH receptor on FRTL5 cells. FEBS Lett. 1987;215:316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rapoport B, Chazenbalk GD, Jaume JC, McLachlan SM. The thyrotropin (TSH) receptor: interaction with TSH and autoantibodies. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:673–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mueller S, Kleinau G, Jaeschke H, Neumann S, Krause G, Paschke R. Significance of ectodomain cysteine boxes 2 and 3 for the activation mechanism of the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31638–31646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Islam MN, Briones-Urbina R, Bakó G, Farid NR. Both TSH and thyroid-stimulating antibody of Graves' disease bind to an Mr 197,000 holoreceptor. Endocrinology. 1983;113:436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kohn LD, Valente WA, Laccetti P, Cohen JL, Aloj SM, Grollman EF. Multicomponent structure of the thyrotropin receptor: relationship to Graves' disease. Life Sci. 1983;32:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koizumi Y, Zakarija M, McKenzie JM. Solubilization, purification, and partial characterization of thyrotropin receptor from bovine and human thyroid glands. Endocrinology. 1982;110:1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heyma P, Harrison LC. Precipitation of the thyrotropin receptor and identification of thyroid autoantigens using Graves' disease immunoglobulins. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1090–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McQuade R, Thomas CG, Jr, Nayfeh SN. Covalent crosslinking of thyrotropin to thyroid plasma membrane receptors: subunit composition of the thyrotropin receptor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;246:52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parmentier M, Libert F, Maenhaut C, et al. Molecular cloning of the thyrotropin receptor. Science. 1989;246:1620–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nagayama Y, Kaufman KD, Seto P, Rapoport B. Molecular cloning, sequence and functional expression of the cDNA for the human thyrotropin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1989;165:1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Misrahi M, Loosfelt H, Atger M, Sar S, Guiochon-Mantel A, Milgrom E. Cloning, sequencing and expression of human TSH receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1990;166:394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Russo D, Chazenbalk GD, Nagayama Y, Wadsworth HL, Seto P, Rapoport B. A new structural model for the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor, as determined by covalent cross-linking of TSH to the recombinant receptor in intact cells: evidence for a single polypeptide chain. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1607–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loosfelt H, Misrahi M, Atger M, et al. Cloning and sequencing of porcine LH-hCG receptor cDNA: variants lacking transmembrane domain. Science. 1989;245:525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ascoli M, Segaloff DL. On the structure of the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:27–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loosfelt H, Pichon C, Jolivet A, et al. Two-subunit structure of the human thyrotropin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3765–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ban T, Kosugi S, Kohn LD. Specific antibody to the thyrotropin receptor identifies multiple receptor forms in membranes of cells transfected with wild-type receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid: characterization of their relevance to receptor synthesis, processing, structure, and function. Endocrinology. 1992;131:815–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Misrahi M, Milgrom E. Cleavage and shedding of the TSH receptor. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997;137:599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]