Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether there is a relation between statin utilisation and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality in populations with different levels of coronary risk, and whether the relation changes over time.

Design

Ecological study using national databases of dispensed medicines and mortality rates.

Setting

Western European countries with similar public health systems.

Main outcome measures

Population CHD mortality rates (rate/100 000) as a proxy for population coronary risk level, and statin utilisation expressed as Defined Daily Dose per one Thousand Inhabitants per Day (DDD/TID), in each country, for each year between 2000 and 2012. Spearman's correlation coefficients between CHD mortality and statin utilisation were calculated. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the relation between changes in CHD mortality and statin utilisation over the years.

Results

12 countries were included in the study. There was a wide range of CHD mortality reduction between the years 2000 and 2012 (from 25.9% in Italy to 57.9% in Denmark) and statin utilisation increase (from 121% in Belgium to 1263% in Denmark). No statistically significant relations were found between CHD mortality rates and statin utilisation, nor between changes in CHD and changes in statin utilisation in the countries over the years 2000 and 2012.

Conclusions

Among the Western European countries studied, the large increase in statin utilisation between 2000 and 2012 was not associated with CHD mortality, nor with its rate of change over the years. Factors different from the individual coronary risk, such as population ageing, health authority programmes, guidelines, media attention and pharmaceutical industry marketing, may have influenced the large increase in statin utilisation. These need to be re-examined with a greater emphasis on prevention strategies.

Keywords: coronary mortality, statin utilization

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to examine the relation over time between statin utilisation and coronary heart disease (CHD) in Western European countries

We conducted an ecological study investigating whether the rate of increase in statin utilisation was associated with the rate of decrease in CHD mortality among a sample of Western European countries in the period 2000–2012.

The sample of countries had a wide range of CHD mortality rates and similar public health systems.

CHD mortality was used as a proxy measure of population cardiovascular risk levels.

Limitations include a small sample size and the lack of data regarding: the patients' adherence to statin treatment, the indications for statin treatment—whether primary or secondary prevention—and the effects of pharmaceutical industry campaigns on doctors' decisions about statin treatment in different countries.

Introduction

A substantial decrease in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality has been observed in Western European countries during the past four decades,1 2 to a great extent attributable to reductions in major risk factors in the populations, mainly dyslipidaemia and hypertension.3–5

Statins reducing cholesterol synthesis were first used in the 1990s. Several clinical trials in both primary and secondary prevention have shown that statins reduce coronary events and mortality.6 7 Since their introduction, the utilisation of statins has increased rapidly in all Western European countries, although the level of utilisation varies widely.8–10 Current guidelines on CHD prevention propose that the decision to start statin treatment in primary prevention should be based on the assessment of the global risk of developing CHD in individual patients.11 12 According to the guidelines, the treatment of high-risk individuals should be prioritised. This has resulted in multiple strategies among Western European countries to enhance the prescribing of statins in high-risk individuals, including producing and disseminating guidelines, quality indicators—such as targets for lipid levels—and financial incentives.13 A reasonable consequence, at the population level, could be that more people are treated in high-risk countries, leading to a higher utilisation of statins in these countries than in countries with low risk. At the same time, of course, statin utilisation should lower the risk by time, which makes prediction more complicated.

It has previously been reported that doctors tend to underestimate coronary risk in high-risk patients,14 and that statins are overused in individuals with low cardiovascular risk, whereas they are underused in those at high risk.15 16 This may result in under-treatment of high-risk patients whereas low-risk individuals may be unnecessarily treated, potentially leading to adverse effects and increased expenditure. Despite the debate about the appropriateness of current prescribing patterns and the effectiveness of strategies to target statin treatment based on CHD risk,17–19 whether there is an association between coronary risk in the general population and statin utilisation, and whether this persists over the years, has not been investigated.

In the present study, we analysed the relation between the changes over time in CHD mortality and statin utilisation in a number of Western European countries with a wide spectrum of the level of population coronary risk. Our research questions were (1) whether there would be an association between statin utilisation and CHD mortality when different countries are compared at a certain point in time, and (2) whether the level of change in statin utilisation over the years would be associated with the level of decrease in CHD mortality. The analysis of these relationships may improve our understanding of the appropriateness of statin utilisation.

Methods

This was an ecological study comparing statin utilisation and CHD mortality between 2000 and 2012, among Western European countries. The countries were chosen to reflect differences in population coronary risk and according to the availability of both, mortality and statin utilisation data. All these countries have similar public health systems, or statutory health insurance with universal coverage, based on direct taxation or income-related contribution.20

CHD mortality was used as a proxy measure of population CHD risk level, since it has less diagnostic variance than measurement of individual risk factors. There is evidence that countries with higher levels of risk factors have higher CHD mortality, and a close association has previously been demonstrated between changes in risk factor levels and changes in CHD mortality.21–23 Data with ICD-10 codes I20-I25 (ischaemic heart disease, including angina, acute myocardial infarction, subsequent myocardial infarction, complications following acute myocardial infarction and chronic ischaemic heart disease) were extracted from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) database.24 All ages were included. To take into account the possible bias of different age classes in the different countries, we used age-standardised mortality data calculated by the OECD Secretariat, using the total OECD population for 2010 as the reference population, expressed as rates/100 000 population.

Utilisation of statins was assessed using publicly available databases on prescription sales in the countries.20 The population coverage of each database was 100% (95% for the Netherlands). Since they represent more than 90% of lipid-lowering drugs used in all the countries studied, only statin utilisation was analysed. To make international comparisons in different periods, the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification and the standard international method for estimating drug use across populations—the Defined Daily Dose (DDD) per one Thousand Inhabitants per Day (DDD/TID)25—were used. The ATC code C10AA and the 2013 DDDs update were used.

Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata V.13 (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA). Volumes of statin utilisation (DDD/TID) were plotted against CHD mortality rates in each country between the years 2000 and 2012. The panel of data was constructed using the reshape command in Stata, so that the values for each country were in different columns, one row for each year. Since each country was represented 13 times, the cluster command in Stata was used to adjust for repeated measures. Spearman's correlation coefficients between CHD mortality and statin utilisation for each year between 2000 and 2012 were calculated. The relationship between changes in CHD mortality and statins over the years was studied with linear regression, using CHD mortality as a response and statin utilisation and years as independent variables.

Results

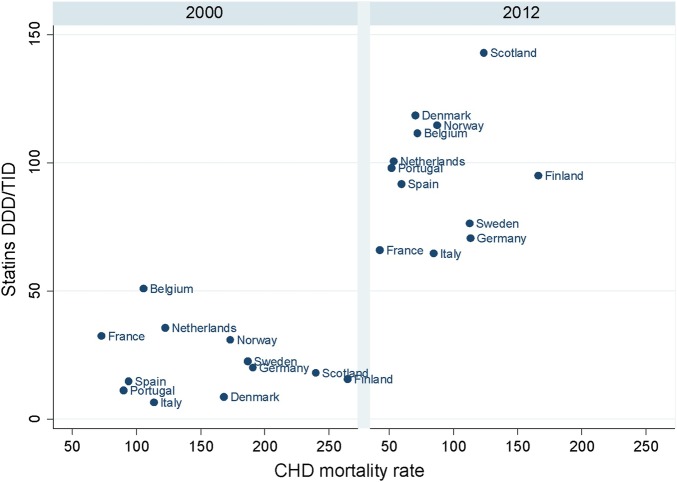

There was data available from 12 countries: Finland, Scotland, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, Belgium, Spain, Portugal and France. Data from other Western European countries were not available or limited to a few years (Ireland, Austria), or the data used a drug codification system that was not directly comparable to ATC (England and Wales). CHD mortality rates and statin utilisation in the years 2000 and 2012 are shown in figure 1. A wide range of CHD mortality reduction (from 25.9% in Italy to 57.9 in Denmark) and statin utilisation increase (from 121% in Belgium to 1263% in Denmark) was observed between 2000 and 2012 (table 1). There was no statistically significant correlation between statin utilisation and CHD mortality in any of the years between 2000 and 2012. No significant relation was found between changes in statin utilisation between 2000 and 2012 on the one hand, and the changes in CHD mortality over the same period on the other hand (β coefficient 0.35, 95% CI −0.61 to 1.33).

Figure 1.

Statin utilisation and CHD mortality rates in the years 2000 and 2012. CHD mortality data from OECD Health Statistics 2014.24 Italy missing data 2004–2005, Portugal missing data 2004–2006. Statin utilisation data from national databases on prescription sales in each country. Belgium data available from 2004 onwards, France until 2009. Statins data from databases on prescription sales. Belgium data available from 2004 onwards. France until 2009. Scotland until 2010. CHD, coronary heart disease; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Table 1.

Standardised CHD mortality rates/100 000 and statin utilisation as DDD/TID

| CHD mortality |

Statin utilisation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2000 | 2012 | 2000 | 2012 | CHD mean annual change (95% CI) | Statins mean annual change (95% CI) |

| Finland | 264.6 | 166 | 17 | 94.9 | −7.9 (−8.6 to −7.2) | 7.2 (6.5 to 8.0) |

| Scotland | 239.9 | 123.8 | 17.2 | 142.8 | −10.2 (−10.9 to −9.6) | 14.1 (12.7 to 15.4) |

| Germany | 190.8 | 113.4 | 21.4 | 70.5 | −7.1 (−7.8 to −6.4) | 4.5 (4.0 to 4.9) |

| Sweden | 186.6 | 112.7 | 21.8 | 76.3 | −6.5 (−6.9 to −6.1) | 5.3 (4.9 to 5.6) |

| Norway | 173.2 | 87.2 | 30.9 | 114.6 | −7.5 (−8.5 to −6.5) | 7.6 (7.1 to 8.1) |

| Denmark | 168 | 70.6 | 8.6 | 117.3 | −8.5 (−9.4 to −7.7) | 10.3 (9.4 to 11.2) |

| The Netherlands | 122.5 | 53.6 | 35.6 | 99.9 | −6.0 (−6.5 to −5.4) | 6.3 (5.8 to 6.8) |

| Italy | 113.5 | 84.1 | 6.4 | 64.5 | −2.7 (−3.4 to −2.0) | 4.8 (4.6 to 5.0) |

| Belgium | 121.3 | 62.6 | 50.9 | 112.7 | −5.1 (−5.6 to −4.7) | 8.5 (7.8 to 9.3) |

| Spain | 94 | 59.5 | 14.7 | 91.6 | −3.0 (−3.3 to −2.8) | 6.6 (6.0 to 7.2) |

| Portugal | 88.6 | 51.7 | 11.1 | 98.9 | −3.4 (−4.0 to −2.9) | 8.5 (7.9 to 9.2) |

| France | 72.8 | 42.6 | 32.3 | 66.0 | −2.9 (−3.1 to −2.7) | 3.5 (2.9 to 4.1) |

| Mean | 153 (60) | 85 (36) | 22 (13) | 95 (23) | −5.9 (−7.4 to −4.3) | 7.2 (5.4 to 9.1) |

Data as in figure 1.

Summary data are expressed as mean (SD) or (95% CI).

DDD/TID, Defined Daily Dose per one Thousand Inhabitants per Day.

Coronary mortality in 2012 was highly correlated to CHD in 2000 (p=0.002), whereas no significant correlation was found between statins in 2000 and 2012.

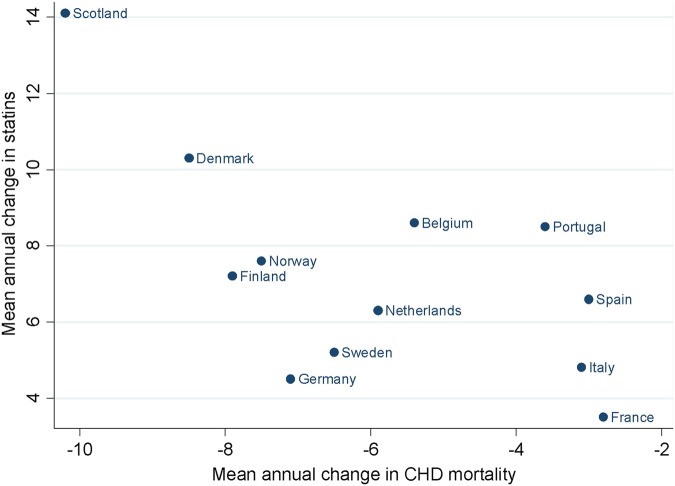

The mean annual change in CHD mortality was plotted against the mean annual change in statin utilisation (figure 2). The mean annual change in statin utilisation varied widely across all countries and was unrelated to the annual change in CHD mortality. Countries with similar decreases in CHD mortality rates (France, Italy, Spain and Portugal) had very different increases in statin utilisation. Conversely, similar increases in statin utilisation were observed in countries with very different reductions in CHD mortality rates. Scotland showed the largest rates of CHD mortality reduction and statin utilisation increase. Taken together, the countries showed a wide range of statin increase, with no apparent relation to the reduction in CHD mortality.

Figure 2.

Mean annual changes in statin utilisation and CHD mortality rates between 2000 and 2012. CHD, coronary heart disease.

Discussion

We found a decrease in CHD mortality and an increase in statin utilisation in all the Western European countries studied. If we accept CHD mortality as a marker of population cardiovascular risk, the relation between statins and CHD mortality may be considered from two angles: as an effect of statins on cardiovascular risk, or as changes in statin utilisation following changes in risk levels. However, when the different countries were compared, there was no evidence that higher statin utilisation was associated with lower CHD mortality, nor was there evidence that a high increase in statin utilisation between 2000 and 2012 was related to a larger reduction in CHD mortality.

The overall reduced CHD mortality might be considered as an effect of the increased utilisation of statins. Although several clinical studies have demonstrated that statins reduce the cardiovascular mortality in primary and secondary prevention,26–28 the decrease in CHD mortality rates in Western countries started well before statin therapy became available, due to improvement of risk factors, as a result of population-based interventions.29 Moreover, clinical trials in primary and secondary prevention show that statins lower the absolute risk of coronary death by less than 1–3.5%,30 which represents a small proportion of the observed reduction. Consequently, it is difficult to demonstrate any population impact of statin utilisation on CHD mortality. This was confirmed in a Swedish study including a large sample of municipalities, where no correlation was shown between statin utilisation and acute myocardial infarction incidence or mortality.31

We recently observed that statin utilisation is higher in Stockholm, Sweden, which is a relatively high-risk area, compared to Sicily, Italy, with a lower population risk level.32 However, the analysis of the time trend of changes in statin utilisation and CHD mortality rates in these regions between 2000 and 2011 showed that statin utilisation increased more rapidly in Sicily, where the reduction in CHD mortality was slower, whereas a smaller increase occurred in Stockholm, with a larger reduction in CHD mortality. Such discordance between time trends may indicate that the doctors' attitude to initiating statin treatment is influenced by factors not directly related to the actual patient risk, such as the doctors' gender and length of clinical experience, patients' attitudes to medicines, drug reimbursement policies, prescribing restrictions and marketing by pharmaceutical companies.13 33 34

Interpreting the relation between statin utilisation and CHD mortality cannot be limited to the direct relation between drug therapy and clinical outcome. Pharmaceutical expenditure has increased in all European countries during the past decade due to the ageing population, new and expensive medicines, the growing prevalence of chronic diseases, rising patient expectations and greater treatment intensity due to the reduction of the threshold to prevent cardiovascular disease.35–37 In the case of statins, health authorities in many countries have introduced measures to increase the prescribing of low-cost generic versus patented statins to reduce expenditure without compromising care.9 Educational interventions and disease management programmes have also been initiated by health authorities to promote the use of statins in high-risk groups, especially where there is perceived undertreatment.38 39 This includes patients with diabetes and a history of stroke. The policy reforms conducted in the different countries have resulted in economical savings while also stimulating an increased prescribing of statins.13

Strengths and limitations

The populations we studied represent the real world; therefore they were different from patients included in clinical trials, who are highly selected.40 There was a wide range of CHD mortality rates among countries, which allowed analysis of changes in statin utilisation in countries with different levels of coronary risk.

There are some limitations to our study. We assumed that CHD mortality represented the population coronary risk. However, about half of the changes in CHD mortality can be explained by changes in risk factors, whereas the other half are due to treatment or to unknown factors.41 Differences in the relative proportion of changes in risk factors among countries may have influenced the utilisation of statins. This study has limited statistical power due to small sample size. Ours is an ecological study, but we did not have access to information on individual patient link between CHD risk and statin utilisation. Therefore, our results at country level may not be applicable to single patients (ecological fallacy).42 A critical issue regarding the effectiveness of statin therapy is the persistence of treatment. Poor adherence to treatment is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality.43 Adherence to lipid-lowering treatment shows wide variation, ranging from 37% to 80%,44 with lower rates in women, young patients, those with low income, patients taking statins for primary prevention45 and when a statin is prescribed for secondary prevention by a primary care physician, rather than by a cardiologist or neurologist.46 Differences in the discontinuation rate of statins among countries might have a role in the relation between statin utilisation and CHD mortality. However, we could not assess this in our study as we did not have access to specific patient data, but only to aggregated statin utilisation data.

We also do not know the influence of extensive marketing campaigns by the pharmaceutical industries on doctors' decision about statin treatment in each country. This may be an important factor in treatment decisions, especially targeting low-risk individuals.47 Also, the media debate about the benefit of giving statins to all those over 50 years, independently from risk scoring, versus the concern about adverse effects, especially myopathy and increased risk of diabetes,48–51 may have had different impacts both on doctors and patients in different countries. The extent of statin utilisation for either primary or secondary prevention in each country was not investigated. Cross-sectional studies in European countries have shown large variations in the attainment of treatment targets, in primary and secondary prevention.52 53 Doctors' willingness to prescribe statins in primary prevention may also change over time, due to reimbursement changes or guidelines restrictions.54–56 Higher prescription rates have been reported in women and the elderly.31 57 There is also a socioeconomic gradient in the utilisation of statins. More patients with higher income and educational levels start statin treatment compared to patients with lower income, especially in secondary prevention.58–60 The differences among countries might have affected the pattern for prescribing statins.

Clinical implications

Among the Western European countries studied, CHD mortality decreased by approximately 40% whereas statin utilisation increased more than threefold between 2000 and 2012. However, this large growth in statin utilisation over the years did not appear to be related to the coronary risk in the population or to the changes over the years. Factors other than coronary risk, such as demographic changes, socioeconomic factors, healthcare policies—including educational programmes—and pharmaceutical industry marketing, should be taken into account to explain the rapid increase in statin utilisation among Western European countries. On the other hand, although statins have proved effective in the appropriate clinical setting,6 7 whether they are appropriately prescribed to those who benefit most, that is, high-risk individuals and whether statins are effective and safe in otherwise healthy people, are matters for debate.61–63 Since CHD is largely dependent on health factors,64 such as diet and exercise, the apparent lack of association we observed between CHD mortality and statin utilisation supports the need for greater implementation of population life-style changes instead of additional initiatives to further enhance statin utilisation to reduce the burden of CHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carsten Telschow, AOK Research Institute, Berlin, Iain Bishop, NHS National Services, Scotland, Maria Juhasz and Desirée Loikas, Stockholm County Council, Sweden, for providing statin data from Germany, Scotland and Sweden, respectively and Julie Ramsey, National Records of Scotland, for calculating standardised Scottish CHD mortality rates.

Footnotes

Contributors: FV was responsible for the design, implementation, analysis and reporting of the study. LB, L-ES, BG and BW provided substantial contributions to the design, analysis and interpretation of data, and all critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kesteloot H, Sans S, Kromhout D. Dynamics of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in Western and Eastern Europe between 1970 and 2000. Eur Heart J 2006;27:107–13. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P et al. . Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2950–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmieri L, Bennett K, Giampaoli S et al. . Explaining the decrease in coronary heart disease mortality in Italy between 1980 and 2000. Am J Public Health 2010;100:684–92. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björck L, Rosengren A, Bennett K et al. . Modelling the decreasing coronary heart disease mortality in Sweden between 1986 and 2002. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1046–56. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Modelling the decline in coronary heart disease deaths in England and Wales, 1981–2000: comparing contributions from primary prevention and secondary prevention. BMJ 2005;331:614 10.1136/bmj.38561.633345.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills EJ, WU P, Chong G et al. . Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170255 patients from 76 randomized trials. QJM 2011;104:109–24. 10.1093/qjmed/hcq165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naci H, Brugts JJ, Fleurence R et al. . Comparative benefits of statins in the primary and secondary prevention of major coronary events and all-cause mortality: a network meta-analysis of placebo-controlled and active-comparator trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013;20:641–57. 10.1177/2047487313480435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walley T, Folino-Gallo P, Stephens P et al. . EuroMedStat Group. Trends in prescribing and utilization of statins and other lipid lowering drugs across Europe 1997–2003. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;60:543–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02478.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godman B, Wettermark B, van Woerkom M et al. . Multiple policies to enhance prescribing efficiency for established medicines in Europe with a particular focus on demand-side measures: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol 2014;5:106 10.3389/fphar.2014.00106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G et al. . Cardiovascular prevention guidelines in daily practice: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I, II, and III surveys in eight European countries. Lancet 2009;373:929–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60330-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al. . European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): the Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2012;33:1635–701. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 181. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. July 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181 [PubMed]

- 13.Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M et al. . Policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol 2011;1:141 10.3389/fphar.2010.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backlund L, Bring J, Strender LE. How accurately do general practitioners and students estimate coronary risk in hypercholesterolaemic patients? Prim Health Care Res Dev 2004;5:145–52. 10.1191/1463423604pc179oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Staa TP, Smeeth L, Ng ESW et al. . The efficiency of cardiovascular risk assessment: do the right patients get statin treatment? Heart 2013;99:1597–602. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy C, Bennett K, Fahey T et al. . Statin use in adults at high risk of cardiovascular disease mortality: cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). BMJ Open 2015;5:e008017 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brugts JJ, Deckers JW. Statin prescription in men and women at cardiovascular risk: to whom and when? Curr Opin Cardiol 2010;25:484–9. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833cd58f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petursson H, Getz L, Sigurdsson JA et al. . Can individuals with a significant risk for cardiovascular disease be adequately identified by combination of several risk factors? Modelling study based on the Norwegian HUNT 2 population. J Eval Clin Pract 2009;15:103–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tunstall-Pedoe H. Starting statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Heart 2013;99:1547–8. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drug Consumption Databases in Europe. Master document. Updated version February 2015. http://www.icf.uab.es/ca/pdf/publicacions/DU_inventory_master.pdf

- 21.Menotti A, Lanti M, Kromhout D et al. . Forty-year coronary mortality trends and changes in major risk factors in the first 10 years of follow-up in the seven countries study. Eur J Epidemiol 2007;22:747–54. 10.1007/s10654-007-9176-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijeysundera HC, Machado M, Farahati F et al. . Association of temporal trends in risk factors and treatment uptake with coronary heart disease mortality, 1994-2005. JAMA 2010;303:1841–7. 10.1001/jama.2010.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capewell S, Ford E, Croft J et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors trends and potential for reducing coronary heart disease mortality in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:120–30. 10.2471/BLT.08.057885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health statistics 2014. http://www.oecd.org/health/healthdata

- 25.WHO. Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC/DDD index2013 2013. http://www.hoccno/atc_ddd_index/WHO

- 26.Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF et al. . Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD004816 10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L et al. , Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012;380:581–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford ES, Capewell S. Proportion of the decline in cardiovascular mortality disease due to prevention versus treatment: public health versus clinical care. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:5–22. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson A, Temple NJ. The case for statins: has it really been made? J R Soc Med 2004;97:461–4. 10.1258/jrsm.97.10.461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson S, Molstad S, Karlberg C et al. . No connection between the level of exposition to statins in the population and the incidence/mortality of acute myocardial infarction: an ecological study based on Sweden's municipalities. J Negat Results Biomed 2011;10:6 10.1186/1477-5751-10-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vancheri F, Wettermark B, Strender L-E et al. . Trends in coronary heart disease mortality and statin utilization in two European areas with different population risk levels: Stockholm and Sicily. Int Cardiovasc Forum 2014;3:140–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vancheri F, Strender L-E, Backlund LG. General Practitioners' coronary risk estimates, decisions to start lipid-lowering treatment, gender and length of clinical experience: their interactions in primary prevention. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2013;14:394–402. 10.1017/S146342361200059X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sketris I, Ingram Langille E, Lummis H.2007. Optimal prescribing and medication use in Canada. Challenges and opportunities. http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/index.php.

- 35.Wettermark B, Godman B, Jacobsson B et al. . Soft regulations in pharmaceutical policy making: an overview of current approaches and their consequences. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2009;7:137–47. doi:0.2165/11314810-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mousnad MA, Shafie AA, Ibrahim MI. Systematic review of factors affecting pharmaceutical expenditures. Health Policy 2014;116:137–46. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kildemoes HW, Støvring H, Andersen M. Driving forces behind increasing cardiovascular drug utilization: a dynamic pharmacoepidemiological model. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;66:885–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03282.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraeyman J, Van Hal G, Godman B et al. . The potential influence of various initiatives to improve rational prescribing for proton pump inhibitors and statins in Belgium. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2013;13:141–51. 10.1586/erp.12.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Woerkom M, Piepenbrink H, Godman B et al. . Ongoing measures to enhance the efficiency of prescribing of proton pump inhibitors and statins in The Netherlands: influence and future implications. J Comp Eff Res 2012;1:527–38. 10.2217/cer.12.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eichler HG, Abadie E, Breckenridge A et al. . Bridging the efficacy–effectiveness gap: a regulator's perspective on addressing variability of drug response. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:495–506. 10.1038/nrd3501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capewell S, O'Flaherty M. What explains declining coronary mortality? Lessons and warnings. Heart 2008;94:1105–8. 10.1136/hrt.2008.149930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piantadosi S, Byar DP, Green SB. The ecological fallacy. Am J Epidemiol 1988;127:893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Vera MA, Bhole V, Burns LC et al. . Impact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:684–98. 10.1111/bcp.12339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schedlbauer A, Davies P, Fahey T. Interventions to improve adherence to lipid lowering medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3:CD004371 10.1002/14651858.CD004371.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemstra M, Blackburn D, Crawley A et al. . Proportion and risk indicators of nonadherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:574–80. 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Citarella A, Kieler H, Sundström A et al. . Family history of cardiovascular disease and influence on statin therapy persistence. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014;70:701–7. 10.1007/s00228-014-1659-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfe S. Rosuvastatin: winner in the statin wars, patients' health notwithstanding. BMJ 2015;350:h1388 10.1136/bmj.h1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCartney M. Medicine and the Media. Statins for all? BMJ 2012;345:e6044 10.1136/bmj.e6044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mansi I, Frei CR, Wang C-P et al. . Statins and new-onset diabetes mellitus and diabetic complications: a retrospective cohort study of US healthy adults. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1599–610. 10.1007/s11606-015-3335-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cederberg H, Stančaková A, Yaluri N et al. . Increased risk of diabetes with statin treatment is associated with impaired insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion: a 6 year follow-up study of the METSIM cohort. Diabetologia 2015;58:1109–17. 10.1007/s00125-015-3528-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Unintended effects of statins in men and women in England and Wales: population based cohort study using the QResearch database. BMJ 2010;340: c2197 10.1136/bmj.c2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banegas JR, López-García E, Dallongeville J et al. . Achievement of treatment goals for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice across Europe: the EURIKA study. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2143–52. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kotseva K, Wood D, Backer GD et al. . EUROASPIRE III: a survey on the lifestyle, risk factors and use of cardioprotective drug therapies in coronary patients from 22 European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2009;16:121–37. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283294b1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pettersson B, Hoffmann M, Wändell P et al. . Utilization and costs of lipid modifying therapies following health technology assessment for the new reimbursement scheme in Sweden. Health Policy 2012;104:84–91. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Damiani G, Federico B, Bianchi C et al. . The impact of regional co-payment and national reimbursement criteria on statins use in Italy: an interrupted time-series analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:6 10.1186/1472-6963-14-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martikainen JEL, Saastamoinen LKP, Korhonen MJP et al. . Impact of restricted reimbursement on the use of statins in Finland: a register-based study. Med Care 2010;48:761–6. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e41bcb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kildemoes HW, Hendriksen C, Andersen M. Drug utilization according to reason for prescribing: a pharmacoepidemiologic method based on an indication hierarchy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:1027–35. 10.1002/pds.2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Selmer R, Sakshaug S, Skurtveit S et al. . Statin treatment in a cohort of 20 212 men and women in Norway according to cardiovascular risk factors and level of education. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:355–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03360.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomsen RW, Johnsen SP, Olesen AV et al. . Socioeconomic gradient in use of statins among Danish patients: population-based cross-sectional study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;60:534–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02494.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rasmussen JN, Gislason GH, Rasmussen S et al. . Use of statins and beta-blockers after acute myocardial infarction according to income and education. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:1091–7. 10.1136/jech.2006.055525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abramson J, Wright JM. Are lipid-lowering guidelines evidence-based? Lancet 2007;369:168–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60084-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golomb B, Evans M. Statin adverse effects. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2008;8:373–418. 10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK et al. . Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet 2011;378:1231–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Sacks FM et al. . Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men: benefits among users and nonusers of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation 2006;114:160–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]