Abstract

Objectives

Multimorbidity is the presence of 2 or more medical conditions. This increasingly used assessment has not been assessed in a surgical population. The objectives of this study were to assess the prevalence of multimorbidity and its association with common outcome measures.

Design

A cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

A UK-based multicentre study, included participants between July and October 2014.

Participants

Consecutive emergency (non-elective) general surgical patients admitted to hospital, aged over 65 years.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures were (1) the prevalence of multimorbidity and (2) the association between multimorbidity and frailty; the rate and severity of surgery; length of hospital stay; readmission to hospital within 30 days of discharge; and death at 30 and 90 days.

Results

Data were collected on 413 participants aged 65–98 years (median 77 years, (IQR (70–84)). 51.6% (212/413) participants were women. Multimorbidity was present in 74% (95% CI 69.7% to 78.2%) of the population and increased with age (p<0.0001). Multimorbidity was associated with increasing frailty (p for trend <0.0001). People with multimorbidity underwent surgery as often as those without multimorbidity, including major surgery (p=0.03). When comparing multimorbid people with those without multimorbidity, we found no association between length of hospital stay (median 5 days, IQR (1–54), vs 6 days (1–47), (p=0.66)), readmission to hospital (64 (21.1%) vs 18 (16.8%) (p=0.35)), death at 30 days (14 (4.6%) vs 6 (5.6%) (p=0.68)) or 90-day mortality (28 (9.2%) vs 8 (7.6%) (p=0.60)).

Conclusions and implications

Multimorbidity is common. Nearly three-quarters of this older emergency general surgical population had 2 or more chronic medical conditions. It was strongly associated with age and frailty, and was not a barrier to surgical intervention. Multimorbidity showed no associations across a range of outcome measures, as it is currently defined. Multimorbidity should not be relied on as a useful clinical tool in guidelines or policies for older emergency surgical patients.

Keywords: GERIATRIC MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY, SURGERY, Multimorbidity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We found multimorbidity to be very common when defined simplistically as two or more chronic conditions.

In a large multicentre observational setting, the study did not demonstrate any associations between adverse outcome and multimorbidity.

Introduction

Multimorbidity is defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic medical conditions in one individual. In developed countries, approximately one-quarter of adults can be defined as multimorbid,1 2 and more than half of older Americans possess three or more chronic illnesses.3 Multimorbidity reflects the complex interplay between multiple diseases and includes both physical and mental health conditions.4 It is indicative of the fact that as opposed to participants in the clinical trial (from whom evidence is usually derived), older patients in clinical practice rarely present acutely with a single pathology.5 Additionally, as one would expect, where multimorbidity is observed, polypharmacy often coexists due to medical management of chronic diseases. This iatrogenic component of managing several coexistent diseases coupled with polypharmacy is also thought to amplify the complexities encountered in managing such patients.

Many studies detail comorbidity in nearly all branches of medicine,6 however, the specific concept of multimorbidity (two or more pathologies) is still novel in medicine. Few studies exist that characterise multimorbidity in all patient populations,1 3 and no such studies have been conducted in surgical populations. Therefore, if we are to provide better care for such high-risk patients, there is a need for data that are both representative and contemporary of older patients admitted as surgical emergencies.

The primary aims of this study were to assess the prevalence of multimorbidity in a large representative UK-wide sample population of patients admitted to secondary care with emergency general surgical problems, and measure the amount of polypharmacy present. Secondary aims included: assessment of whether multimorbidity was associated with outcome; prevalence and severity of surgical intervention; rate of hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge; length of hospital stay; and death at 30 and 90 days following index admission.

Methods

An established surgical research collaboration (http://www.opsoc.eu) collected data across five sites within the UK: one in Wales, two in Scotland and two in England. Cardiff, Bristol and Aberdeen sites are large teaching hospitals, which serve urban and rural communities. The Manchester site is an inner city teaching hospital, and the Glasgow site a District General Hospital situated in Greater Glasgow. We studied consecutive patients aged 65 years and over admitted to respective emergency general surgical admissions units over a 4-month period from July to October 2014.

At each site, data collectors were trained in the study protocol and standard operating procedures. All data were collated using password-protected, prepopulated Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. All patient-identifiable data were removed, handled and stored according to local data management guidelines. Data were captured using intranet systems, scrutiny of patient case notes and prescribing charts. We obtained relevant institutional approvals at respective sites. Since this study examined information that is currently collected as part of routine care, it was deemed to be service evaluation and, as such, did not require external ethical approval.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was to estimate the prevalence of multimorbidity. Secondary outcomes measures were the association between multimorbidity and: frailty (measured using the 7-point Canadian Study of Health and Ageing (CSHA) scale); the rate and severity of surgery; length of hospital stay; readmission to hospital within 30 days of discharge; and death at 30 and 90 days.

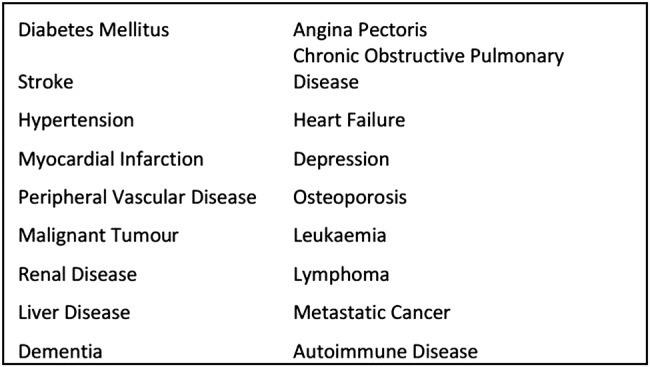

Multimorbidity was defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic diseases. There is no existing formally agreed definition of which conditions should be considered as contributing towards the diagnosis. However, we based our predefined inclusion criteria on the most common conditions identified from an inclusive systematic review published by Diederichs et al.7 This review identified the most common conditions listed in contemporary studies in multimorbidity. The Charlson index is a broad, widely used and well-established tool used to measure comorbidity in clinical practice.8 To ensure that our definition of multimorbidity reflected a broad range of conditions we identified 18 conditions between this index and the systematic review by Diederichs et al. These are listed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conditions used to define multimorbidity.

Within 24 h of admission and prior to any surgical intervention, patients' multimorbidity status was assessed from admission medical records. We assessed and recorded baseline demographic and physiological data: age group (65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years) and gender. Haemoglobin concentration (≤129 g/L classified as anaemia), serum albumin (≤35 g/L classified as low) and the number of current medications (<5 or ≥5) were also recorded. Polypharmacy was defined as more than, or equal to five oral or inhaled medications. To assess frailty we used an established and well-validated seven-point clinical frailty score derived from the CSHA.9 This simple scale estimates an individual's level of frailty through visual observation in combination with an abbreviated review of their current medical records. The seven grades of frailty are: very fit, well, well with treated comorbidities, apparently vulnerable, mildly frail, moderately frail and severely frail.

We recorded whether each person underwent a surgical procedure. The severity of surgery was graded using the five-point BUPA severity of surgery score.10 This score divides the severity of surgery into minor, intermediate, major, major plus and complex major. For purposes of data analysis, we grouped the severity of surgery; minor/intermediate surgeries and major/above surgeries. Data were also collected on length of stay (recorded as whole-day integers, with any part of a day rounded upward), readmission to the index hospital (regardless of the readmission diagnosis) within 30 days of discharge from the index surgical admission and death within both 30 days and 90 days of the index admission.

Statistical analysis

Cross-sectional tabulations of categorical variables were tested using a χ2 test of association, and a Wilcoxon rank test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. The following were determined by the literature as preconceived scientifically justified explanatory covariates: sex, age, anaemia, low albumin and polypharmacy. Independent scientifically justified covariates were fitted as predictors using an unadjusted logistic regression model and ORs with 95% CIs presented. A final parsimonious multivariable logistic model was derived using a forward stepping regression model by including any covariate that exhibited statistical significance (p<0.05) in any of the three univariable analyses. All statistical calculations were conducted using STATA V.13 (Stata Corp).

Results

Data were collected on 413 participants. Two had insufficient data recorded and were excluded from the data analysis. Therefore, 411 participants were included in the analysis; 92 people in Wales (Cardiff), 128 in England (51 in Manchester and 77 in Bristol) and 191 in Scotland (45 in Glasgow and 146 in Aberdeen). The median age was 77 years (IQR 70–84). The study cohort included 212 (51.6%) women and 199 (48.4%) men, who did not differ in age distribution (p=0.36). Seventy-four per cent of participants (304/411) were classified as multimorbid (95% CI 69.7% to 78.2%). The prevalence of multimorbidity was associated with increasing age (p<0.0001) but not gender (p=0.62) (table 1). The prevalence of multimorbidity did not differ between study sites with a range of 68.6% in Manchester to 80.5% in Bristol (p=0.61).

Table 1.

Prevalence of multimorbidity, with age and sex

| Overall | Multimorbidity |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Number (%) | 411 (100) | 304 (74.0) | 107 (26.0) | |

| Age, years (IQR) | 77 (70–84) | 78 (72–85) | 72 (65–89) | <0.0001 |

| Aged 65–74 years (%) | 169 (41.1) | 106 (62.7) | 63 (37.3) | <0.0001 |

| 75–84 years | 150 (36.5) | 121 (80.7) | 29 (19.3) | |

| Over 85 years | 92 (22.4) | 77 (83.7) | 15 (16.3) | |

| Women (%) | 212 (51.6) | 53 (25.0) | 159 (75.0) | 0.62 |

| Men (%) | 199 (48.4) | 54 (27.1) | 145 (72.9) | |

There were 183 (44.5%) people who met the definition of anaemia. Of those participants with multimorbidity, 146 (48.0%) were anaemic compared with 37 (34.6%) of the non-multimorbid group (p=0.02). Low serum albumin was recorded in 171 (41.6%) of the population. Hypoalbuminaemia was more common in those with multimorbidity (45%) (p=0.02). Polypharmacy was recorded in 279 participants (67.9%), and was more common in the multimorbid group (78.9%) compared with the non-multimorbid group (36.4%) (p<0.0001). For the whole population, the seven-point frailty scale showed 73 (17.9%) of patients were fit, 52 (12.8%) well, 89 (21.8%) well with treated comorbid conditions, 81 (19.8%) apparently vulnerable, 56 (13.7%) mildly frail, 41 (10.1%) moderately frail and 16 (3.9%) severely frail (data were not available for 3 patients for this variable). Nearly 28% of all participants were mildly frail or above. Increasing frailty was associated with multimorbidity (p for trend <0.0001).

In total, 79 (19.2%) people underwent a surgical procedure. The number of participants undergoing surgical intervention did not differ between the groups (55, (18.1%) of the multimorbid group versus 24 (22.4%) of the non-multimorbid group, p=0.33). Category of surgery was unrecorded for nine participants. Of those who underwent surgery, 46 (65.7%) were coded as major or above in severity. More major surgeries were conducted in the multimorbid group with 42 (91.3%) procedures occurring in this group compared with 17 (70.8%) minor/intermediate procedures (p=0.03). All results are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Characterisation of the multimorbid and non-multimorbid populations

| Overall | Multimorbidity |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No | |||

| Number (%) | 411 | 304 (74.0) | 107 (26.0) | |

| Haemoglobin (≤129 g/L) | 183 (44.5) | 146 (79.8) | 37 (20.2 | 0.02 |

| Albumin, (≤35 g/L) | 171 (41.6) | 137 (80.1) | 34 (19.9) | 0.02 |

| Polypharmacy (yes %) | 279 (67.9) | 240 (86.0) | 39 (14.0) | <0.0001 |

| Frailty (Canadian Study of Health and Ageing scale) | ||||

| Very fit | 73 (17.9) | 32 (43.8) | 41 (56.2) | <0.0001 |

| Well | 52 (12.8) | 28 (53.8) | 24 (46.2) | Test for trend |

| Well, with comorbidity | 89 (21.8) | 72 (80.9) | 17 (19.1) | |

| Apparently vulnerable | 81 (19.8) | 65 (80.2) | 16 (19.8) | |

| Mildly frail | 56 (13.7) | 49 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | |

| Moderately frail | 41 (10.1) | 39 (95.1) | 2 (14.9) | |

| Severely frail | 16 (3.9) | 16 (100) | 0 | |

| Operation (yes %) | 79 (19.2) | 55 (69.6) | 24 (30.4) | 0.33 |

| Minor or intermediate surgery | 24 (34.3) | 7 (29.2) | 17 (70.8) | 0.03 |

| Major or more severe surgery | 46 (65.7) | 41 (91.3) | 4 (8.7) | |

| Missing | 9 | |||

| Length of hospital stay (days, 95% CI) | 9.3 (8.1 to 10.5) | 9.1 (7.5 to 10.4) | 9.8 (7.2 to 12.5) | 0.29 |

| Readmission to hospital (yes %) | 82 (19.9) | 64 (78.0) | 18 (22.0) | 0.35 |

| Death within 30 days (yes %) | 20 (4.9) | 14 (70.0) | 6 (30.0) | 0.68 |

| Death within 90 days (yes %) | 36 (8.8) | 28 (77.8) | 8 (22.2) | 0.60 |

The median length of stay (LOS) (or time spent in hospital until death) was 5½ days (range 1–90 days, IQR 1–72 days). Eleven people had missing data for LOS. The average LOS was 5 days (1–47) in the multimorbid group versus, 6 days (1–54) in the non-morbid group (p=0.66). Eighty-two patients were readmitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge. Of these, 64 had multimorbidity. When compared with the 18 without multimorbidity, there was no difference in the incidence of readmission (p=0.35). Twenty participants (4.9%) died within 30 days, and 36 participants (8.8%) died within 90 days of hospital admission. There was no statistically significant difference in 30-day or 90-day mortality between the multimorbid and non-multimorbid groups (p=0.68 and 0.60, respectively). Full results are shown in table 2.

The unadjusted ORs for death within 30 and 90 days for those with multimorbidity were 0.81 (95% CI 0.30 to 2.17, p=0.60) and 1.24 (95% CI 0.58 to 2.80, p=0.68) respectively, and 1.31 (95% CI 0.74 to 2.34) for readmission (table 3).

Table 3.

Univariable logistic regression for death at 30 days, 90 days and readmission

| Unadjusted OR for death at 30 days, (95% CI), p value | Unadjusted OR for death at 90 days, (95% CI), p value | Unadjusted OR for readmission, (95% CI), p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multimorbidity | 0.81 (0.30 to 2.17), 0.68 | 1.24 (0.55 to 2.81), 0.60 | 1.31 (0.74 to 2.34), 0.35 |

| Haemoglobin (≤129 g/L) | 1.56 (0.63 to 3.84), 0.33 | 1.83 (0.92 to 3.67), 0.09 | 1.58 (0.97 to 2.57), 0.06 |

| Albumin, (≤35 g/L) | 2.74 (1.07 to 7.02), 0.04 | 3.09 (1.50 to 6.37), 0.002 | 1.27 (0.78 to 2.07), 0.33 |

| Polypharmacy (yes %) | 1.44 (0.51 to 4.05), 0.49 | 1.24 (0.58 to 2.66), 0.58 | 1.88 (1.07 to 3.33), 0.03 |

| Mildly frail or worse | 2.77 (1.11 to 6.84), 0.03 | 3.29 (1.64 to 6.60), 0.001 | 1.81 (1.08 to 3.02), 0.02 |

| Operation (yes %) | 1.03 (0.33 to 3.16), 0.96 | 1.04 (0.44 to 2.48), 0.93 | 1.46 (0.82 to 2.61), 0.19 |

Main effects included in the adjusted multivariable model are in bold.

Univariate analysis between readmission and haemoglobin, albumin, polypharmacy, frailty (grouped as mildly frail or worse) and operation (yes or no) are shown in table 3. Albumin, polypharmacy and frailty were associated with the outcomes of interest, and were included in all the final multivariate models. The adjusted OR (aOR) between death at 30 days and multimorbidity was 0.94 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.78; p=0.84) after adjustment for albumin, polypharmacy and frailty. The aOR for death at 90 days and readmission to hospital were 0.83 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.08; p=0.69) and 0.94 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.78; 0.84), respectively.

Discussion

This is the first study in a surgical population assessing multimorbidity, indicating its prevalence and correlation with outcome in an emergency (non-elective) setting. We identified multimorbidity (defined as two or more chronic diseases) in 74% of our population. The population was also shown to be frail. We did not find any association between multimorbidity and length of hospital stay, hospital readmission or death.

We have shown that 83.7% of our population aged over 85 years, and 62.7% aged 65–74 years have multimorbidity. There are no directly comparable studies of general surgical patients (or any other surgical subspecialty) with which to compare and contrast our findings. However, there are studies that have assessed the prevalence of multimorbidity in other areas of medicine. These studies commonly use information derived from existing databases in different population groups. In 2012, Barnett et al1 conducted an analysis of Scottish primary care health records in 1 750 000 people of all ages. They identified multimorbidity in 23.2% of the study population. In those aged 65–84 years, the figure was 64.9% increasing to 81.5% in those aged 85 years and over. A recent community-based representative Swiss study of 3714 people estimated the prevalence of multimorbidity to be 56.3% in people aged 35–75 years, but found the figure to be much lower in people who self-reported multimorbidity.11 In the 63 people aged over 65 years who had multimorbidity objectively measured, they found multimorbidity to have a prevalence of 70%. This is similar to rates of multimorbidity identified in our patients group.

Unsurprisingly, as anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia are markers of poor health following surgical intervention,12 13 our multimorbid population had a high prevalence of both. A commonly used marker of comorbidity is polypharmacy, as the majority of people with several coexisting medical conditions will be taking medications. Again we found a strong association between polypharmacy and multimorbidity. As multimorbidity and its impact on health are due, in part, to the interactions between health and medication, future studies would benefit from reviewing types of medications and dosages with respect to outcomes in multiple morbid surgical patients.

This study reports the first findings with regard to the relationships between multimorbidity, the choice of conservative versus emergency surgical intervention and complexity of surgery. Our findings demonstrated that multimorbidity does not appear to be a barrier to emergency surgery, and that the emergency surgical procedures that these patients underwent were of a more complex nature. Primary malignancy and metastases contribute to both the diagnosis of multimorbidity and emergency general surgical workload. Additionally, conditions such as autoimmune disease or peripheral vascular disease (which are classed as multimorbid conditions) are associated with other common emergency general surgical conditions (eg, mesenteric ischaemia). Hence our findings regarding the rate and type of surgery are likely to be simply reflective of the typical emergency general surgical patients observed during the study period, and as such, may represent confounding. Therefore, less inference should be drawn when comparing our findings with elective general surgical patients.

Our results did not identify any association between multimorbidity and our selected outcome measures. Multimorbidity is not a barrier to emergency surgical intervention, which can be viewed positively by an increasingly aged and multimorbid population. It is possible that a longer follow-up period, or alternative outcome measures, such as postoperative complications, would have identified a positive correlation. However, our results did show that multimorbidity was strongly associated with frailty which is, in turn, associated with poor outcome in surgical populations,14–17 including emergency general surgery.18 This finding has been consistent across a range of frailty measures and populations. Future studies should directly compare multimorbidity and frailty in order to assess which is a better predictive measure in the assessment of the older elective and emergency surgical patient.

This study was designed as part of a larger epidemiological project to collect comprehensive data sets of older surgical patients undergoing emergency surgical intervention. Multimorbidity was one of our chosen exploratory areas of study. We would have expected to detect some sign of true association (positive or otherwise) in a population of this size. However, the study did not start with predetermined power calculations to test outcome associations between multimorbidity and outcomes. Nonetheless, a sample of over 400 participants represents a pragmatic data gathering operation, and to detect no signal regarding the use of multimorbidity alone implies that multimorbidity is not, and is unlikely to become, a useful predictor of outcome in the emergency general surgical patient.

Future studies should, therefore, focus on more sophisticated estimation of multimorbidity. The most simplistic approach would be to simply increase the number of conditions needed to define multimorbidity. Koller et al19 showed that three conditions taken together predicted a higher level of care provision after several years of follow-up in a large German cohort. Alternatively, the effect of multimorbidity could be stratified by certain conditions, for example, hypertension or diabetes, which for the majority of those affected, these common conditions are treated and well controlled. It is also likely that future definitions of multimorbidity will become more sophisticated in other ways, for example, to include only active or untreated disease. Based on our findings, we would recommend future research in this area to explore a range of inclusion criteria when considering how to define and further characterise the multimorbid, emergency general surgical population. Our study has also demonstrated that polypharmacy is prevalent and a more detailed medication study of drug numbers and classes is warranted. It may also be appropriate for future studies, particularly those considering an intervention, to consider where clinical input may be useful for example, pharmacist review of medication or physician review prior to surgery.

More detailed epidemiological data, for example, socioeconomic status, would allow a more accurate picture of the nature and generalisability of future data. In addition, as data were collected over summer and autumn, it is possible that the data recorded would have differed in the winter months. Additional comorbidity and increased winter pressures on hospital systems may have substantially affected our results and is a consideration for future studies. Although we did not detect a difference between the prevalence of multimorbidity across our five different sites, another potential bias is interobserver and site variability. All the sites and observers were trained in the use of the study standard operating procedures, and all data were collected via a prepopulated form and collated by the lead author. However, it is possible that different observers systematically assessed patient multimorbidity differently, and this should also be noted. Nevertheless, the data collected were mainly objective data, and fixed at the time of assessment (eg, age, list of medications, mortality data, etc), and hence, the possibility of bias introduced by interobserver differences is minimal. Future large-scale studies should also ensure that centralised multimorbidity and frailty training is part of the study protocol, in an attempt to minimise this limitation.

Despite our study limitations, data were collected in five different sites; Cardiff (Wales), Manchester and Bristol (England), Glasgow and Aberdeen (Scotland) spread widely across the whole of mainland UK. These sites include urban and rural populations, and both academic and non-academic institutions. Additionally, other markers of generalisability, such as the prevalence of frailty, which we measured as 27.7% (mildly frail or worse), were consistent with what we would expect in a UK older emergency surgical population.20 As such, we feel that our population is representative of the UK population.

In conclusion, the results from this large, UK-wide representative sample are the first description of multimorbidity in an emergency surgical population. We have demonstrated that multimorbidity is highly prevalent; with nearly three-quarters of emergency general surgical patients aged over 65 years having two or more medical conditions. Those with multimorbidity underwent complex surgical procedures more frequently than those without multimorbidity. However, we did not detect any correlations between multimorbidity and a range of commonly used outcome measures. This study used the standard definition of multimorbidity, namely two conditions. We would advocate that future studies of this nature consider more sophisticated definitions of multimorbidity, and a threshold level for the number of conditions affecting outcome should be explored. Alternatively, by defining definitions of active or quiescent chronic disease more precisely, or with a greater focus on attendant polypharmacy, better predictive models of multimorbidity could be identified. We would also encourage that multimorbidity be compared to other methods of estimating ill health in older people, such as frailty.

Footnotes

Contributors: JH, KM, MJS, PKM, LP and SJM conceived the study. BC performed the statistical analysis. JH, KM, MS, PKM, LP, SJM, JL, CM, HST, MG, AT and NHA contributed to data collection. JH, KM, MS, PKM, LP, BC, SJM, JL, CM, HST, MG, AT and NHA contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:223–8. 10.1370/afm.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians: American geriatrics society expert panel on the care of older adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:E1–E25. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercer SW, Gunn J, Bower P et al. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. BMJ 2012;345:e5559 10.1136/bmj.e5559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee S. Multimorbidity–older adults need health care that can count past one. Lancet 2015;385:587–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61596-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yurkovich M, Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J et al. A systematic review identifies valid comorbidity indices derived from administrative health data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:3–14. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diederichs C, Berger K, Bartels DB. The measurement of multiple chronic diseases–a systematic review on existing multimorbidity indices. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:301–11. 10.1093/gerona/glq208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489–95. 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. http://codes.bupa.co.uk/home (accessed 24 Mar 2014).

- 11.Pache B, Vollenweider P, Waeber G et al. Prevalence of measured and reported multimorbidity in a representative sample of the Swiss population. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1515 10.1186/s12889-015-1515-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partridge J, Harari D, Gossage J et al. Anaemia in the older surgical patient: a review of prevalence, causes, implications and management. J R Soc Med 2013;106:269–77. 10.1177/0141076813479580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Story DA. Perioperative medicine for older patients. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011;25:vii–viii. 10.1016/j.bpa.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P et al. Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:78–83. 10.1016/j.archger.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:901–8. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson TN, Wallace JI, Wu DS et al. Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:37–42; discussion 42–34 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L et al. Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg 2013;206:544–50. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewitt J, Moug SJ, Middleton M et al. Prevalence of frailty and its association with mortality in general surgery. Am J Surg 2015;209:254–9. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koller D, Schon G, Schafer I et al. Multimorbidity and long-term care dependency–a five-year follow-up. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:70 10.1186/1471-2318-14-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Partridge JS, Harari D, Dhesi JK. Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age Ageing 2012;41:142–7. 10.1093/ageing/afr182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]