Abstract

Objective

To date, no study has prospectively examined the association between social capital (SC) in the community and oral health. The aim of this longitudinal cohort study was to examine the association between both community-level and individual-level SC and tooth loss in older Japanese people.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

We utilised data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) performed in 2010 and 2013 and conducted in 525 districts.

Participants

The target population was restricted to non-institutionalised people aged 65 years or older. Participants included 51 280 people who responded to two surveys and who had teeth at baseline.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was loss of remaining teeth, measured by the downward change of any category of remaining teeth, between baseline and follow-up.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 72.5 years (SD=5.4). During the study period, 8.2% (n=4180) lost one or more of their remaining teeth. Among three community-level SC variables obtained from factor analysis, an indicator of civic participation significantly reduced the risk of tooth loss (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99). The individual-level SC variables ‘hobby activity participation’ and ‘sports group participation’ were also associated with a reduced risk of tooth loss (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.81 to 0.95 and OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.82 to 0.99, respectively).

Conclusions

Living in a community with rich SC and individuals with good SC is associated with lower incidence of tooth loss among older Japanese people.

Keywords: Social capital, Multilevel analysis, Tooth loss, Cohort study, Panel data

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first prospective cohort study to examine the association between both community-level and individual-level social capital and tooth loss.

This study surveyed people from 525 communities around Japan in order to gain a wider range of community contextual characteristics.

More than 50 000 people aged 65 years or older participated in baseline and follow-up surveys.

Despite this large sample size, the measurements rely entirely on self-reported data.

Introduction

A higher prevalence of oral diseases causes an individual burden, but it also comes at a social cost. Untreated caries in permanent teeth represent the most prevalent condition, while severe periodontitis and untreated caries in deciduous teeth were the 6th and 10th most prevalent conditions of 291 diseases and injuries.1 Tooth loss often occurs as a result of these diseases; in fact, severe tooth loss was the 36th most prevalent condition.1 In 2010, the direct and indirect global economic burden caused by oral diseases amounted to US$442 billion.2 In addition, oral health affects general health and can exacerbate conditions such as cardiovascular disease,3 4 dementia,5 6 incidence of falls7 and functional disability.8

Widespread inequalities in oral health are observed across the globe, including Japan,9 and are associated with individual and social burdens. Social determinants of health are the most important cause of health inequalities.10 11 Social capital, defined by Kawachi and Berkman12 as “resources that are accessed by individuals as a result of their membership of a network or a group”, is increasingly recognised as a determinant of population health as well as health inequality.13 14 Recently, an increasing number of cross-sectional studies have demonstrated the association between social capital and resources obtained from social capital on oral health.15–18 In spite of a large volume of cross-sectional studies focused on social capital and oral health outcomes, few studies have used longitudinal observation with community-level social capital, rather than individual-level measurements. Owing to the possibility that a community's contextual social capital could affect the health of all its residents, it is important to study population health. Although one prospective study from the UK suggests that the change in an individual's social capital corresponds to plausible changes in an older person's life course, this study did not use community-level social capital measurements.19

Questions regarding the association between community-level social capital and oral health based on longitudinal studies remain unanswered. The aim of this longitudinal cohort study was to examine the association between community-level and individual-level social capital and poor oral health (a reduction in remaining teeth) in elderly Japanese people. We hypothesised that living in high community-level social capital at baseline predicts good oral health at follow-up even when adjusting for individual-level social capital.

Methods

Study setting

We utilised data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). The JAGES Project investigated social, behavioural and health factors in people aged 65 years or older. The JAGES sample was restricted to people who did not already have physical or cognitive disabilities, which were defined as receiving long-term public care insurance benefits. This longitudinal study used the panel data from two surveys. The baseline survey was conducted between August 2010 and January 2012 among 141 452 older people. Self-administered questionnaires were mailed to the entire population of 10 municipalities, and in 14 municipalities, questionnaires were mailed to randomly selected members of the population, based on the official residential registers obtained from the respective municipal governments. A total of 92 272 people responded to the questionnaire (response rate=65.2%). The follow-up survey was conducted between October 2013 and December 2013. Self-administered questionnaires used for the follow-up survey were subsequently mailed to the same municipalities and respondents. Collectively, 62 438 individuals completed both the 2010 and 2013 questionnaires.

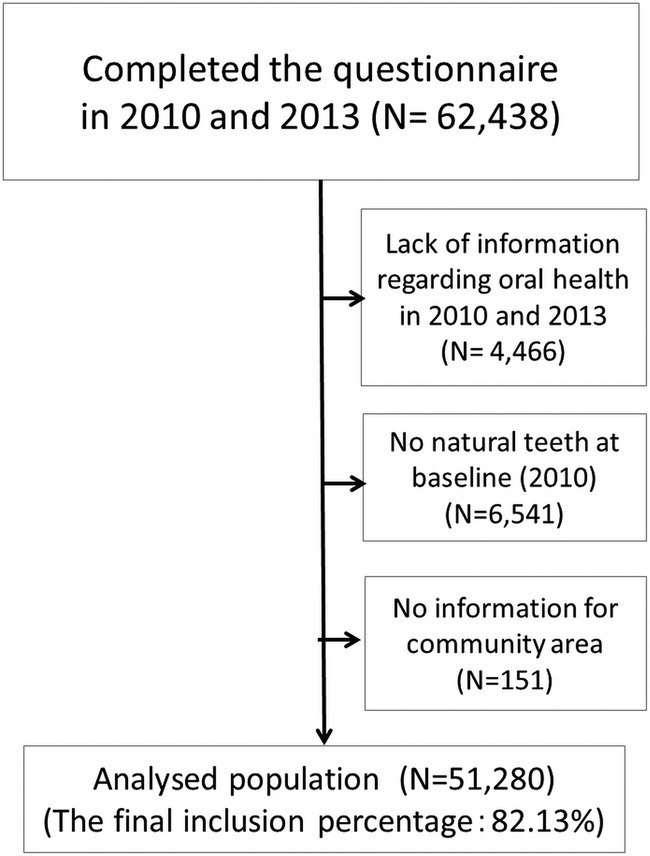

Of these respondents, 4466 were excluded because of a lack of information regarding oral health in 2010 or 2013. We excluded another 6541 individuals who had no natural teeth at baseline (2010), and 151 individuals whose information for their residential area could not be obtained. Finally, 51 280 respondents from 525 districts were included in our analyses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data from 51 280 respondents were included in the analysis.

Outcome variables

The outcome variable used was dichotomous and defined as a ‘reduction of remaining teeth or not’ between baseline and follow-up. In both surveys, we asked for the number of remaining teeth in the following categories: ‘≥20 teeth’; ‘10–19 teeth’; ‘1–9 teeth’; ‘no natural teeth’. At the follow-up survey, if respondents chose a category with a smaller number of teeth compared to that of baseline, they were defined as people who had experienced a reduction in the number of their remaining teeth during the interim period. Data on respondents who had no natural teeth at baseline were excluded from multilevel analysis.

Predictor variables

Individual-level social capital

The individual-level social capital used was participation in each community activity (volunteer groups, sports groups/clubs, hobby activity group), community trust, community attachment and social support (receive emotional support, provide emotional support, receive instrumental support) in 2010.

The response categories used for community activity participation variables were ‘once or more per week’ and ‘less than once per week’. Community trust was measured by asking two yes/no questions: ‘Do you trust the people who live in your local area?’ and, ‘Do you think that it is important to be helpful to other people in your local area?’ Community attachment was measured with the yes/no question, ‘Do you have an attachment to your local area?’ Social support was measured with the following three yes/no questions: ‘Do you have someone who listens to your concerns and complaints?’ (categorised as ‘receive emotional support’); ‘Do you listen to someone else's concerns and complaints?’ (provide emotional support); and ‘Do you have someone who looks after you when you become sick?’ (receive instrumental support).

Community-level social capital

We presumed that respondents who lived in the same districts were exposed to the same degree of community-level social capital (Saito M, Kondo N, Aida J, et al. Development of an instrument for community-level social capital among Japanese older people: the JAGES Study. Submitted 2016, J Epidemiol Community Health). Community-level social capital variables were obtained from factor analysis. At first, rates of each individual-level social capital response in each small district were calculated. Then, using 525 small districts as the analysis unit, factor analysis was conducted and three factors were obtained: civic participation (participation in volunteer groups, sports groups and hobby activities), social cohesion (community trust and attachment) and reciprocity (received/provided emotional support; received instrumental support). Factor scores for each small district were used as community-level social capital variables.

Covariates

As in the studies mentioned previously, the following questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics, baseline health status and risk factors for oral health were included in the analyses as covariates: age, sex, educational attainment, annual household income, comorbidity, smoking, density of dental offices, population density and number of teeth at baseline. Age was grouped into five categories: 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and 85 years or older. Educational attainment was categorised as follows: <6, 6–9, 10–12 and ≥13 years. Annual household income was categorised as follows: <$20 000 (<¥2 000 000), $20 000–$29 999 (¥2 000 000–¥2 999 999), $30 000–$39 999 (¥3 000 000–¥3 999 999) and ≥$40 000 (≥¥4 000 000) (US$1=¥100). Comorbidity was measured by using the yes/no question, ‘Do you receive treatment now?’. Smoking was categorised as follows: non-smoking, non-smoking now and quit more than 5 years ago, non-smoking now and quit within 4 years and smoking now. We included density of dental offices as a continuous variable in the models. Population density was categorised as follows: urban area (≥1500 people/km2), suburban area (1000–1500 people/km2) and rural area (<1000 people/km2).

Data analysis

The data were analysed by multilevel logistic regression analyses. We calculated OR and 95% CI for respondents who had a reduction in the number of remaining teeth during the study period. Since 51 280 respondents lived in 525 small districts, a two-level model (community-level and individual-level) was used. We put emphasis on the theoretical importance of the covariates and included all covariates in the multivariate model. If data were missing for explanatory variables, the corresponding observations were assigned to ‘missing’ categories. The significance level was set at p<0.05. We used SPSS V.19.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA) for factor analysis and Stata V.13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) for multilevel analysis.

Ethical issues

JAGES respondents were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, and that completing and returning the self-administered questionnaire by mail indicated their consent for participation in the study.

Results

Of 51 280 respondents, 23 924 men and 27 356 women were included in the analysis. The average age of the 51 280 respondents was 72.5 years (SD=5.4). Among the respondents, 8.2% (n=4180) reported a reduction in the number of their remaining teeth. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each variable. Participants who were older, with less education, lower incomes, living in rural areas, with no emotional social support, having between 10 and 19 teeth, or who were smokers tended to have a higher incidence of tooth loss.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of respondents and reduction of remaining teeth at follow-up (n=51280)

| Reduction of remaining teeth (N, %) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No |

Yes |

Total | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Man | 21 652 | 91 | 2272 | 9 | 23 924 |

| Woman | 25 448 | 93 | 1908 | 7 | 27 356 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 65–69 | 16 367 | 93 | 1187 | 7 | 17 554 |

| 70–74 | 14 899 | 92 | 1281 | 8 | 16 180 |

| 75–79 | 10 748 | 91 | 1089 | 9 | 11 837 |

| 80–84 | 2798 | 89 | 346 | 11 | 3144 |

| 85+ | 1111 | 88 | 152 | 12 | 1263 |

| Education (years) | |||||

| <6 | 541 | 88 | 77 | 12 | 618 |

| 6–9 | 19 210 | 91 | 1923 | 9 | 21 133 |

| 10–12 | 16 832 | 93 | 1299 | 7 | 18 131 |

| ≥13 | 8957 | 93 | 702 | 7 | 9659 |

| Annual household income | |||||

| <$10 000 | 4727 | 90 | 504 | 10 | 5231 |

| $10 000–$19 999 | 13 758 | 92 | 1208 | 8 | 14 966 |

| $20 000–$29 999 | 10 198 | 92 | 832 | 8 | 11 030 |

| $30 000–$39 999 | 6472 | 93 | 502 | 7 | 6974 |

| ≥$40 000 | 4768 | 93 | 364 | 7 | 5132 |

| Living area | |||||

| Urban area | 12 844 | 93 | 897 | 7 | 13 741 |

| Suburban area | 22 231 | 92 | 1987 | 8 | 24 218 |

| Rural area | 12 025 | 90 | 1296 | 10 | 13 321 |

| Hobby activity | |||||

| Less than once per week | 23 139 | 91 | 2207 | 9 | 25 346 |

| Once or more per week | 16 695 | 93 | 1232 | 7 | 17 927 |

| Sports group | |||||

| Less than once per week | 28 213 | 92 | 2596 | 8 | 30 809 |

| Once or more per week | 10 384 | 93 | 756 | 7 | 11 140 |

| Volunteer group | |||||

| Less than once per week | 32 222 | 92 | 2797 | 8 | 35 019 |

| Once or more per week | 4688 | 92 | 388 | 8 | 5076 |

| Community trust | |||||

| No | 12 544 | 92 | 1098 | 8 | 13 642 |

| Yes | 32 310 | 92 | 2879 | 8 | 35 189 |

| Community reciprocity | |||||

| No | 19 386 | 92 | 1657 | 8 | 21 043 |

| Yes | 25 252 | 92 | 2294 | 8 | 27 546 |

| Community attachment | |||||

| No | 7947 | 92 | 709 | 8 | 8656 |

| Yes | 37 904 | 92 | 3356 | 8 | 41 260 |

| Receive emotional support | |||||

| No | 2305 | 90 | 268 | 10 | 2573 |

| Yes | 42 452 | 92 | 3677 | 8 | 46 129 |

| Provide emotional support | |||||

| No | 2516 | 90 | 295 | 10 | 2811 |

| Yes | 42 015 | 92 | 3622 | 8 | 45 637 |

| Receive instrumental support | |||||

| No | 2127 | 92 | 176 | 8 | 2303 |

| Yes | 42 834 | 92 | 3788 | 8 | 46 622 |

| Number of teeth in 2010 | |||||

| ≥20 | 19 902 | 92 | 1825 | 8 | 21 727 |

| 10–19 | 13 775 | 90 | 1508 | 10 | 15 283 |

| 1–9 | 13 423 | 94 | 847 | 6 | 14 270 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Non-smoking | 26 527 | 93 | 2045 | 7 | 28 572 |

| Non-smoking now, quit before 5 years | 10 309 | 92 | 941 | 8 | 11 250 |

| Non-smoking now, quit within 4 years | 2096 | 90 | 240 | 10 | 2336 |

| Smoking | 4304 | 89 | 551 | 11 | 4855 |

| Do you have hospital treatment? | |||||

| Yes | 32 255 | 92 | 2771 | 8 | 35 026 |

| No | 11 154 | 91 | 1052 | 9 | 12 206 |

Table 2 shows the results of the multilevel logistic analysis. In the sex-adjusted and age-adjusted model, a significant association between community-level social capital and incidence of tooth loss was observed at two variables, ‘civic participation’ and ‘social cohesion’ (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.80 to 0.89 and OR 1.14; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.20, respectively). Among the individual-level social capital variables, ‘hobby activity participation’ and ‘sports group participation’ were significant for reducing the risk of tooth loss (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.76 to 0.88 and OR 0.82 95% CI 0.76 to 0.90, respectively). When all variables were included in one model, living in a rich community-level social capital district at baseline and the incidence of tooth loss were observed at the variable ‘civic participation’ (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99). The individual-level social capital variables ‘hobby activity participation’ and ‘sports group participation’ still had significant associations (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.81 to 0.95 and OR 0.90 95% CI 0.82 to 0.99, respectively).

Table 2.

Data are presented as ORs (95% CIs), p value of reduction of remaining teeth of the respondents (n=51 280)

| Sex and age adjusted analysis OR (95% CI), p value |

Multivariate analysis OR (95% CI), p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (ref woman) | ||||

| Man | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.85) | <0.001 | ||

| Age (ref 65–69 years) | ||||

| 70–74 | 1.26 (1.16 to 1.37) | <0.001 | ||

| 75–79 | 1.54 (1.40 to 1.68) | <0.001 | ||

| 80–84 | 1.97 (1.73 to 2.25) | <0.001 | ||

| 85+ | 2.23 (1.85 to 2.69) | <0.001 | ||

| Education (ref ≥13 years) | ||||

| <6 | 1.67 (1.29 to 2.16) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.10 to 1.85) | 0.008 |

| 6–9 | 1.31 (1.19 to 1.44) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.06 to 1.29) | 0.002 |

| 10–12 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.15) | 0.412 | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.11) | 0.887 |

| Annual household income (ref≥$40 000) | ||||

| <$10 000 | 1.42 (1.23 to 1.64) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.12 to 1.50) | <0.001 |

| $10 000–$19 999 | 1.14 (1.01 to 1.29) | 0.039 | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.24) | 0.14 |

| $20 000–$29 999 | 1.05 (0.93 to 1.20) | 0.426 | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.19) | 0.514 |

| $30 000–$39 999 | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.16) | 0.936 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.16) | 0.908 |

| Living area (ref rural area) | ||||

| Urban area | 0.63 (0.57 to 0.70) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.57 to 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Suburban area | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.95) | 0.001 |

| Community-level social capital | ||||

| Civic participation | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.89) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.017 |

| Social cohesion | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.20) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | 0.135 |

| Reciprocity or support | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) | 0.28 | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.05) | 0.550 |

| Density of dental office | ||||

| Density of dental office per 10 000 people | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.91) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08) | 0.876 |

| Individual-level social capital | ||||

| Hobby activity | 0.81 (0.76 to 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95) | 0.002 |

| Sports group | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.027 |

| Volunteer group | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | 0.722 | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.21) | 0.194 |

| Community trust | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.58 | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) | 0.760 |

| Community reciprocity | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.10) | 0.377 | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.15) | 0.152 |

| Community attachment | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.354 | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.06) | 0.404 |

| Receive emotional support | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.94) | 0.004 | 0.89 (0.75 to 1.05) | 0.179 |

| Provide emotional support | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.001 | 0.89 (0.76 to 1.04) | 0.132 |

| Receive instrumental support | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.22) | 0.626 | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.34) | 0.151 |

| Number of teeth in 2010 (ref ≥20 teeth) | ||||

| 10–19 | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.23) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.14) | 0.142 |

| 1–9 | 0.61 (0.56 to 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (ref non-smoking) | ||||

| Non-smoking now, quit before 5 years | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) | 0.665 | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16) | 0.351 |

| Non-smoking now, quit within 4 years | 1.30 (1.12 to 1.51) | 0.001 | 1.39 (1.19 to 1.62) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1.48 (1.32 to 1.66) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.41 to 1.77) | <0.001 |

| Do you have hospital treatment? (ref no) | ||||

| Yes | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.26) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Random-effects parameters | ||||

| Community-level variance Ωμ (SE) | 0.0038 (0.0062) | |||

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between both community-level and individual-level social capital and oral health using longitudinal data. The results suggest that living in a community with a higher density of civic participation (a measurement of community-level social capital) at baseline was associated with future low risk of tooth loss. This association was still significant even after adjusting for individual-level social participation variables that were also beneficial to oral health.

The results of the present longitudinal analysis were similar to previous cross-sectional studies. In Japan, a previous study demonstrated a significant positive association between social participation and dental health status among older people.20 Another cross-sectional study suggested that community-level horizontal social capital and vertical social capital have different effects on health; only the former had a contextual effect on dental status.21 A review of the papers on social capital and oral health also reported the beneficial association between social capital and oral health.16 This review, however, pointed out the need for a longitudinal analysis. The present study adds evidence supportive of an association between social capital and oral health by cohort study. In addition, those people who had 10–19 remaining teeth at baseline tended to lose their teeth (table 2). This was consistent with the results of a previous study in Japan that used data from a nationwide dental survey.22 Therefore, it is important to prevent tooth loss through public health interventions, individual efforts and clinical care.

There are numerous possible pathways between social capital and oral health. Rouxel et al16 summarised the hypothesised pathways linking social capital and oral health: behavioural and psychosocial, via access to oral health services and via policy development. Regarding the behavioural pathway, social capital is considered to affect health behaviours through social contagion and informal social control.12 As an example, one study observed the contagion of smoking cessation following a social network.23 Regarding the psychosocial pathway, social capital is considered to be associated with reducing psychosocial stress, a possible risk factor for oral diseases.24 Through collective efficacy, a community with rich social capital can establish health-promoting policies.12 In this context, we supposed that although population density of dental clinics was sparse during the 1960s–1970s in Japan, the establishment of a dental clinic might be promoted in a community with rich social capital. Improving access to dental care could contribute to oral health in a community because access to dental care has been reported to promote oral health.25

From the present results, social capital may contribute to improvements in oral health. Previous intervention studies attempted to promote health through the enhancement of social capital.26–28 Participation in the community salon (a resident-centred community intervention programme) contributed to the prevention of incident functional disability.26 28 Hikichi et al28 found that participation in the community salon contributed to the prevention of incident functional disability. Although previous intervention studies related to social capital did not examine the effects on oral health, public health interventions enhancing social capital, as described above,26–28 might improve oral health.

The strengths of our study are its prospective cohort design and its use of panel data. This design was suitable for the inference of causality compared to previous cross-sectional studies. This is the first multilevel study of social capital and oral health using longitudinal data, including both individual-level social capital and community-level social capital. In addition, this study enabled us to consider a wider range of community contextual characteristics by surveying 525 communities in Japan with more than 50 000 older-age participants.

This study has some notable limitations. First, while this survey was large, oral health (in terms of number of remaining teeth) was self-reported and even though the validity of this measure has been well established with respect to objective measures,29–31 the longitudinal change of self-reported dental health was imprecise relative to clinical dental check-ups. Second, the follow-up periods differed between municipalities. Since some municipalities had shorter follow-up periods than others did, it was difficult to conclude causality in this study. Third, our study included no information about changes in social capital. Therefore, there is the possibility that time-varying, confounding factors such as economic changes or natural disasters may have biased our results. However, this study aimed to examine whether baseline social capital was associated with follow-up tooth loss in a cohort study; therefore, we applied the present cohort study design. Even if we could have used change of social capital, it is very difficult to determine causality with only two time point observations.

Conclusion

This large-scale cohort study covered a broad area of this country and has provided evidence that high community-level and individual-level social capital at baseline is associated with a lower incidence of tooth loss at follow-up among older Japanese people.

Acknowledgments

This study used data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES), conducted by the Center for Well-being and Society, Nihon Fukushi University, as one of their research projects.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK and JA participated in the data acquisition and study design, performed statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MS participated in the data acquisition and was an advisor on the study concept, statistical analysis and interpretation, and helped to draft the manuscript. NK, YS, YM, YT and YS participated in data acquisition, helped in the analysis and interpretation, as well as to draft the manuscript. KK, the principal investigator of the JAGES project, helped to develop the idea of the study, participated in the data acquisition, served as an advisor on statistical analysis and interpretation and revised the manuscript. TO, TY, TT and KO participated in the data collection, advised on statistical analysis and interpretation, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study used data from JAGES (the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study), which was supported by MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology-Japan)-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (2009–2013), JSPS(Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) KAKENHI Grant Numbers (22330172, 22390400, 23243070, 23590786, 23790710, 24390469, 24530698, 24683018, 25253052, 25870573, 25870881, 26285138, 26882010, 15H01972), Health Labour Sciences Research Grants (H22-Choju-Shitei-008, H24-Junkanki [Seishu]-Ippan-007, H24-Chikyukibo-Ippan-009, H24-Choju-Wakate-009, H25-Kenki-Wakate-015, H25-Choju-Ippan-003, H26-Irryo-Shitei-003 [Fukkou], H26-Choju-Ippan-006, H27-Ninchisyou-Ippan-001), the Research and Development Grants for Longevity Science from AMED (Japan Agency for Medical Research and development), the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology(24-17, 24-23) , and Japan Foundation For Aging And Health(J09KF00804).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee at Nihon Fukushi University (10-05 and 13-14).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res 2013;92:592–7. 10.1177/0022034513490168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Listl S, Galloway J, Mossey PA et al. Global economic impact of dental diseases. J Dent Res 2015;94:1355–61. 10.1177/0022034515602879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK et al. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003;95: 559–69. 10.1067/moe.2003.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khader YS, Albashaireh ZS, Alomari MA. Periodontal diseases and the risk of coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2004;75:1046–53. 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paganini-Hill A, White SC, Atchison KA. Dentition, dental health habits, and dementia: the Leisure World Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1556–63. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto T, Kondo K, Hirai H et al. Association between self-reported dental health status and onset of dementia: a 4-year prospective cohort study of older Japanese adults from the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES) Project. Psychosom Med 2012;74:241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T, Kondo K, Misawa J et al. Dental status and incident falls among older Japanese: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:pii: e001262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aida J, Kondo K, Hirai H et al. Association between dental status and incident disability in an older Japanese population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:338–43. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aida J, Matsuyama Y, Koyama K et al. Oral health and social determinants. In: Fukai K, ed.. The current evidence of dental care and oral health for achieving healthy longevity in an aging society 2015. Japan Dental Association, 2015:215–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watt RG. Social determinants of oral health inequalities: implications for action. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012;40(Suppl 2): 44–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00719.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social capital, social cohesion, and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, Glymour M, eds. Social epidemiology. 2nd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014:290–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murayama H, Fujiwara Y, Kawachi I. Social capital and health: a review of prospective multilevel studies. J Epidemiol 2012;22:179–87. 10.2188/jea.JE20110128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uphoff EP, Pickett KE, Cabieses B et al. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:54 10.1186/1475-9276-12-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsakos G, Sabbah W, Chandola T et al. Social relationships and oral health among adults aged 60 years or older. Psychosom Med 2013;75:178–86. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827d221b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouxel P, Heilmann A, Aida J et al. Social capital: theory, evidence, and implications for oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2015;43:97–105. 10.1111/cdoe.12141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batra M, Tangade P, Rajwar YC et al. Social capital and oral health. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:ZE10–1. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9330.4900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath C, Bedi R. Influences of social support on the oral health of older people in Britain. J Oral Rehabil 2002;29:918–22. 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouxel P, Tsakos G, Demakakos P et al. Is social capital a determinant of oral health among older adults? Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0125557 10.1371/journal.pone.0125557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi K, Aida J, Kondo K et al. Social participation and dental health status among older Japanese adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e61741 10.1371/journal.pone.0061741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aida J, Hanibuchi T, Nakade M et al. The different effects of vertical social capital and horizontal social capital on dental status: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:512–18. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshino K. Number of present teeth is one of the risk factors for tooth loss. Health Sci Health Care 2011;11:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2249–58. 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vered Y, Soskolne V, Zini A et al. Psychological distress and social support are determinants of changing oral health status among an immigrant population from Ethiopia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011;39:145–53. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crocombe LA, Stewart JF, Brennan DS et al. Is poor access to dental care why people outside capital cities have poor oral health? Aust Dent J 2012;57:477–85. 10.1111/adj.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichida Y, Hirai H, Kondo K et al. Does social participation improve self-rated health in the older population? A quasi-experimental intervention study. Soc Sci Med 2013;94:83–90. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujiwara Y, Sakuma N, Ohba H et al. REPRINTS: effects of an intergenerational health promotion program for older adults in Japan. J Intergener Relatsh 2009;7:17–39. 10.1080/15350770802628901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hikichi H, Kondo N, Kondo K et al. Effect of a community intervention programme promoting social interactions on functional disability prevention for older adults: propensity score matching and instrumental variable analyses, JAGES Taketoyo study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:905–10. 10.1136/jech-2014-205345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglass CW, Berlin J, Tennstedt S. The validity of self-reported oral health status in the elderly. J Public Health Dent 1991;51:220–2. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1991.tb02218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitiphat W, Garcia RI, Douglass CW et al. Validation of self-reported oral health measures. J Public Health Dent 2002;62:122–8. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto T, Kondo K, Fuchida S et al. Validity of self-reported oral health variables: Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES) project. Health Sci Health Care 2012;12:4–12. [Google Scholar]